Missouri river

The Missouri (in English Missouri River, which derives from the Missouri tribe and means "people with wooden canoes") is the longest river of North America. It flows through the northern United States in a southeasterly direction through seven states—Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri—until it drains into the Mississippi River, of which it is its main tributary, very close from the city of San Luis. It has a length of 4,090 km, but if the Mississippi-Missouri system is considered, it reaches 6,275 km, which places it as the fourth longest in the world, after the Amazon, Nile and Yangtze rivers.

It drains a basin of 2,980,000 km², the sixth largest in the world, sparsely populated and with a semi-arid climate that includes parts of ten US states. United States and two Canadian provinces. The major cities that the Missouri runs through are Great Falls, Bismarck, Sioux City, Omaha, and Kansas City.

For more than 12,000 years, many people have relied on the Missouri and its tributaries for livelihoods and transportation. More than ten large groups of Native Americans populated its basin, mostly leading a nomadic lifestyle, depending on the huge herds of bison that once roamed across the Great Plains. The river was first encountered by Europeans in the late 17th century century: it was discovered by the French explorer Étienne de Veniard. The region passed through Spanish and French hands before becoming part of the United States, after the Louisiana Purchase. For a long time it was believed that this river could be part of the Northwest Passage —a waterway that would link the Atlantic and the Pacific—, but when the Lewis and Clark expedition managed to cross its entire length for the first time (1805), It was confirmed that this mythical route through the interior of the continent was nothing more than a legend.

During the 19th century, the Missouri was one of the main avenues for expansion into the Far West. In the early 1800s, the growth of the fur trade caused trappers to explore the region and break new ground. Beginning in the 1830s, pioneers flocked west, first in wagons, then in the increasing number of steamboats that began to operate on the river. Former Native lands in the basin were taken over by settlers, leading to some of the longest and most violent wars against Native peoples in American history.

During the 20th century, the Missouri basin was developed extensively for irrigation, flood control, and power generation. of hydroelectric power. Fifteen dams dammed the main course of the river, with hundreds more in its tributaries. Meanders were reduced and the river was channelized to improve navigation, reducing its length by more than 320 km. Although the lower Missouri River Valley is now a populated and highly productive agricultural and industrial region, heavy development has taken its toll on wildlife and fish populations, as well as water quality.

Several stretches of the Missouri have been declared National Wild and Scenic Rivers: on October 12, 1976, a long stretch of 239.8 km, in Montana; on November 10, 1978, another stretch of 95 km, between Nebraska and South Dakota; and on May 24, 1991, a final stretch of 62.7 km, also between Nebraska and South Dakota.

Course

There are three streams that run down the slopes of the Rocky Mountains of Montana and Wyoming to form the headwaters of the Missouri River, the Jefferson, Madison, and Gallatin Rivers. The longest begins near Brower's Spring, 2800m above sea level, on the southeastern slope of Mount Jefferson in the Centennial Mountains. It flows first west and then north, running first into Hell Roaring Creek, then west into the Red Rock River; it turns northeast to become the Beaverhead, which eventually joins the Big Hole to form the Jefferson River. The Firehole River originates at Madison Lake in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming and joins with the Gibbon River to form the Madison River, while the Gallatin River rises at Gallatin Lake, also in the national park. These two rivers then flow north and northwest into the state of Montana.

The Missouri River officially begins at the confluence of the Jefferson and Madison in Missouri Headwaters State Park near Three Forks, Montana, and is then joined by the Gallatin just 1 mile downstream from its source. The Missouri then passes through Canyon Ferry Lake, a reservoir located west of the Big Belt Mountains. It emerges from the mountains near the town of Cascade and flows northeast to the city of Great Falls, where it plunges over the Great Falls of the Missouri, a series of five major waterfalls. It then runs east through a picturesque region of canyons and lowlands known as the Missouri Breaks, where it receives the Marias River (from 328 km), reaching from the west, then widening into Fort Peck Lake Reservoir a few kilometers above the confluence with the Musselshell River (from 550km). Further on, the river passes through the Fort Peck Dam, and immediately downstream it is met by the Milk River (1170 km) which joins it from the north.

Flowing east across the plains of eastern Montana, the Missouri is greeted by the Poplar River (269 km), coming from the north, before cross the state line and enter North Dakota, where the Yellowstone River, its largest tributary by flow, joins it from the southwest. At the confluence of the two rivers, the Yellowstone is actually the larger river. The Missouri then meanders east past Williston and reaches the tail of Great Lake Sakakawea, an artificial reservoir formed by the great Garrison Dam. Downstream of the dam, the Missouri is then met by the Knife River, which approaches it from the west, and flows south to Bismarck, the capital of North Dakota, where it is joined by the Heart River, which approaches it from the west.. The Missouri then slows down at Lake Oahe Reservoir just before the confluence with the Cannonball River. As it continues south, it eventually reaches Oahe Dam in South Dakota, where it is joined by the Grand, Moreau, and Cheyenne rivers, all coming from the west.

The Missouri then curves broadly to the southeast, meandering across the Great Plains, receiving the Niobrara River and many small tributaries from the southwest. It then proceeds to form the border between South Dakota and Nebraska, and then, after having received the James River from the north, it forms the border between the states of Iowa and Nebraska. In Sioux City the Big Sioux River comes from the north. The Missouri flows south until it reaches the city of Omaha where it receives its longest tributary, the Platte River, which comes from the west. Downstream, the Missouri marks the border between Nebraska and Missouri, then flows between Missouri and Kansas. The Missouri River sways to the east at Kansas City (145,786 pop.), where it receives the Kansas River from the west, and so on in north central from Missouri. It passes south of Columbia and receives the Osage and Gasconade rivers from the south downstream of Jefferson City. The river then skirts the north side of the large city of St. Louis to join the Mississippi River at the Missouri-Illinois border.

Communities along the river

Many of the communities along the Mississippi River are listed below; most have a historical significance or cultural tradition that links them to the river. They are sequenced from the source of the river to its end and the inhabitants all correspond to the 2010 Census.

Locations on the banks of the Missouri River |

|---|

|

Basin

There is only one river with a personality, a sense of humor and the whim of a woman; a river that travels sideways, that interferes in politics, reorganizes the geography and splash in the real estate sector; a river that plays the hidden with you today and tomorrow follows you as a dog with a cookie of dynamite tied to your tail. That river is the Missouri. George Fitch |

With a watershed of 1,371,000 km², the Missouri drains nearly one-sixth of the United States, or just over 5% of North America. Comparable in size to the Canadian province of Quebec, the basin encompasses most of the central Great Plains, extending from the Rocky Mountains in the west to the Mississippi River Valley in the east and toward the southern tip of western Canada to the border of the Arkansas River basin. Compared to the Mississippi River above its confluence, the Missouri is twice as long and drains three times the area. The Missouri accounts for 45% of the annual flow of the Mississippi past the city of St. Louis, and up to a 70% in times of certain droughts.

In 1990, about 12 million people lived in the Missouri basin, almost the entire population of the state of Nebraska, part of that of the states of Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Dakota North, South Dakota, and Wyoming, and small portions of the southern Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. The largest city in the basin is Denver, Colorado, with a population of over 600,000. Denver is the principal city of the Front Range Urban Corridor whose cities had a combined population of more than four million in 2005, making it the largest metropolitan area in the Missouri basin. Other major population centers—mostly located in the southeastern portion of the basin – are Omaha (Nebraska), Nebraska, located north of the confluence of the Missouri and Platte rivers; Kansas City, Missouri – Kansas City, Kansas, located at the confluence of the Missouri with the Kansas River, and the greater St. Louis area, located south of the Missouri River just above its mouth in the Mississippi. In contrast, the northwestern part of the basin is sparsely populated. However, many cities in the Northwest, such as Billings, Montana, are among the fastest growing in the Missouri basin.

With more than 440,000 km² under the plough, the Missouri watershed includes about a quarter of all farmland in the United States, providing more than a third of the country's production of wheat, flax, barley and oats. However, only 28,000 km² of the farmland in the watershed is irrigated. Other 730,000 km² in the basin are dedicated to raising livestock, mainly cattle. Forested areas in the watershed, mostly second growth, total about 113,000 km². Urban areas, on the other hand, represent less than 34,000 km² of land. The most built-up areas are along the main course and on some major tributaries, such as the Platte and the Yellowstone.

Altitude in the basin varies widely, from just over 120 m at the mouth of the Missouri to 4,357 m from the top of Mount Lincoln in central Colorado. The Missouri River itself drops a total of 2,629 m from Brower's Spring, its furthest source. Although the basin plains have very little local vertical relief, the terrain rises about 1.9 m/km from east to west. Elevation is less than 150 m at the eastern edge of the basin, but is more than 910 m above sea level in many places at the base of the Rockies.

The Missouri basin has highly variable weather and precipitation patterns; In general, the basin is defined by a continental climate with hot, humid summers and cold, severe winters. Most of the basin receives an average of 200−250 mm of precipitation per year. However, the westernmost parts of the basin in the Rocky Mountains, as well as the southeastern regions of Missouri can receive up to 1000 mm. The vast majority of precipitation occurs in winter, although the upper basin It is known for short-lived, but intense, summer storms, such as the one it produced in the 1972 Black Hills flood with flooding through Rapid City, South Dakota. Winter temperatures in Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado can drop as low as -51 °C, while summer highs in Kansas and Missouri have reached 49 °C at times.

As one of the major river systems on the continent, the Missouri Basin borders many other major river basins in the United States and Canada. The Continental Divide, which runs along the spine of the Rocky Mountains, forms most of the western border of the Missouri Basin. The Clark River and Snake River, both part of the Columbia River Basin, drain the area west of the Rockies in Montana, Idaho and western Wyoming. The Columbia, Missouri, and Colorado watersheds meet on Three Waters Mountain in the Wind River Range in Wyoming. South of there, the Missouri watershed is bounded on the west by the drainage of the Green River, a tributary of the Colorado, at continuation, in the south with the main channel of the Colorado. Both the Colorado and Columbia rivers flow into the Pacific Ocean. However, a large endorheic drainage, the Great Divide Basin, exists between the Missouri and Green basins in western Wyoming. This area is sometimes considered to be part of the Missouri Basin, even though its waters do not flow to either side of the Continental Divide.

To the north, the lower-elevation Laurentian Divide separates the Missouri basin from the Oldman River, a tributary of the South Saskatchewan River, as well as the Souris River and Sheyenne River and small tributaries of the river Northern Red. All of these streams are part of Canada's Nelson River basin, which empties into Hudson Bay. There are also some large endorheic basins between the Missouri and Nelson basins in southern Alberta and Saskatchewan. The Minnesota and Des Moines rivers, tributaries of the upper Mississippi, drain most of the border area with the eastern part of the basin. of the Missouri. Finally, to the south, the Ozark Mountains and other low divides that run through central Missouri, Kansas, and Colorado separate the Missouri basin from the White River and Arkansas River basins, also tributaries of the Mississippi River.

Main tributaries

Some 95 major tributaries and hundreds of smaller ones feed the Missouri River, receiving most of the larger tributaries as the river approaches its mouth. Most rivers and streams in the Missouri basin run from west to east, following the slope of the Great Plains; however, some eastern tributaries, such as the James, Big Sioux, and Grand systems, flow north–south.

The Missouri's largest runoff tributaries are the Yellowstone (in Montana and Wyoming), the Platte (in Wyoming, Colorado, and Nebraska), and the Kansas–Republican/Smoky Hill and Osage (in Kansas and Missouri). Each of these tributaries drains an area of more than 130,000 km², and has a mean flow greater than 140 m³/s. The Yellowstone River has the highest discharge, despite the fact that the Platte is longer and drains a larger area. In fact, the Yellowstone's flow is about 390 m³/s, accounting for 16% of the total runoff in the Missouri basin and almost double that of on the Platte. At the other end of the scale is the Little Roe River in Montana, which at 61 m long is commonly held to be the world's shortest river.

| Longer tributaries of the Missouri River | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Length | Cuenca | Caudal |

| km | km2 | m3/s | |

| Rio Platte | 1708 | 219 900 | 199 |

| Rio Kansas | 1205 | 154 000 | 209 |

| Río Milk | 1170 | 139 600 | 17,5 |

| Rio James | 1140 | 55 700 | 18.3 |

| Yellowstone River | 1130 | 180 000 | 391 |

| Rio White | 933 | 26 420 | 16.1 |

| Niobrara River | 914 | 36 000 | 48.7 |

| Small river | 900 | 24 700 | 15.1 |

| Río Osage | 793 | 38 300 | 339 |

| Rio Big Sioux | 674 | 20 800 | 37.4 |

The table to the right shows the ten longest tributaries of the Missouri, with their respective basins and flows. The longitude is measured to the hydrologic source, regardless of the naming convention. The main stem of the Kansas River, for example, is 238 km long. However, including the longer headwaters, the 729 km of the Republican River and the 251 km of the Arikaree River, has a total length of 1205 km. Similar nomenclature issues exist on the Platte River, whose longest tributary, the North Platte River, is more than twice as long as the main stream.

The headwaters of the Missouri above Three Forks extend much further upstream than the main course. Measured at the farthest source, at Brower's Spring, the Jefferson River is 480 km long. high, the Missouri River stretches 4,247 km. When combined with the lower Mississippi, the system with the Missouri and its headwaters forms part of the fourth longest river in the world, at 6027 km.

Flow rate

By flow, the Missouri is the ninth largest river in the United States, after the Mississippi, St. Lawrence, Ohio, Columbia, Niagara, Yukon, Detroit, and St. Clair. The latter two, however, are sometimes considered part of a strait between Lake Huron and Lake Erie in the former case, and between Lake Superior and Lake Huron in the latter. Between the rivers of North America in As a whole, the Missouri is the 13th largest, after the Mississippi, Mackenzie, St. Lawrence, Ohio, Columbia, Niagara, Yukon, Detroit, St. Clair, Fraser, Slave, and Koksoak.

Because the Missouri drains a predominantly semi-arid region, its discharge is much smaller and more variable than that of other North American rivers of comparable length. Before damming, the river caused flooding twice a year, once with the April Flood or Cool Spring, with melting snow on the plains basin, and another in the June flood, caused by snowmelt and summer storms in the Rocky Mountains. The latter was far more destructive, with the river increasing to more than ten times its normal flow in some years. The Missouri's discharge is affected by the more than 17,000 reservoirs in its basin, with a total capacity of about 173.9 km³. By regulating flood control, reservoirs dramatically reduce peak flows and increase lows. Evaporation from the reservoirs also significantly reduces runoff from the river, causing an annual loss of more than 3.8 km³ from the mainstem reservoirs alone.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The United States Geological Survey operates fifty-one stream gauges along the Missouri River. The mean flow of the river at Bismarck, 2115.5 km from the mouth, is 621 m³/ s. It is a watershed of 483,000 km², or 35% of the river's total watershed. In Kansas City, 589.2 km from the mouth, the mean flow of the river is 1570 m³/s. The river here drains approximately 1,254,000 km², representing approximately 91% of the entire basin.

The lowest gauge, with a record period greater than fifty years, is at Hermann, Missouri — 157.6 km upstream of the mouth of the Missouri—where the annual mean flow was 2478 m³/s, from 1897 to 2010. Near 1,353,000 km², 98.7% of the basin, lies above Hermann. The highest annual mean was 5,150 m³ /s in 1993, and the lowest of 1181 m³/s in 2006. Discharge extremes vary even more. The highest recorded flow was over 21,000 m³/s on July 31, 1993, during a historic flood. just 17.0 m³/s—caused by the formation of an ice dam—was measured on December 23, 1963.

Upper and Lower Missouri

The upper Missouri River is north of Gavins Point Dam, the last of fifteen hydroelectric dams on the river just upstream of Sioux City, Iowa. The lower Missouri River is 1,350 km to its confluence with the Mississippi just above St. Louis. Lower Missouri has no hydroelectric dams or locks, but it does have a large number of wing dams that inhibit barge traffic by restricting the width of the canal. These wing dams have been blamed for the flooding, and there are currently no plans for the construction of any new locks or dams to replace these wing dams on the Missouri.

Geology

The Rocky Mountains of southwestern Montana at the headwaters of the Missouri River first arose from the Laramide orogeny, a mountain-building episode that occurred from about 70 to 45 million years ago (late Mesozoic to early Cenozoic). This orogeny uplifted Cretaceous rocks along the western side of the Western Interior Seaway, a huge shallow sea that stretched from the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico, which deposited sediments that they now underlie much of the Missouri basin. This Laramide uplift caused the sea to recede and set the stage for the vast drainage system of rivers flowing down the Rocky Mountains and Appalachians, the predecessor of the modern-day Mississippi basin.

The Laramide orogeny is essential in modern Missouri River hydrology, as snow and melting ice from the Rockies provide most of the flow in the Missouri and its tributaries.

The Missouri and many of its tributaries traverse the Great Plains, flowing over or cutting into the Ogallala Group and older mid-Cenozoic sedimentary rocks. The main lower unit of the Cenozoic, the White River Formation, was deposited approximately 35 to 29 million years ago and is composed of claystone, sandstone, limestone, and conglomerate. Channel sandstones and finer riparian fluvial deposits from the The Arikaree Group were deposited between 29 and 19 million years ago. The Miocene Ogallala Formation and the slightly younger Pliocene Broadwater Formation were deposited atop the Arikaree Group, and consist of material eroded out of the Rocky Mountains during a time of increased topographic relief generation; these features extend from the Rocky Mountains near the Iowa border and give the Great Plains much of its gentle but persistent eastward dip, and also constitute an important aquifer.

Immediately before the Quaternary ice age, the Missouri River probably divided into three segments: an upper section, which drained north into Hudson Bay, and the middle and lower sections, which flowed northward. east by the regional slope. As the land subsided in the ice age, a pre-Illinoian glaciation (or possibly the Illinois glaciation) diverted the Missouri River southeast to its present confluence with the Mississippi and caused it to recede. integrated into a single river system that cuts the regional slope. It is believed that the Missouri in western Montana would have flowed once north and then east through the Bear Paw Mountains. Sapphires are found at some points along the river in western Montana. Advances of continental ice sheets diverted the river and its tributaries, causing them to pool in large temporary lakes like glacial lakes, such as the Great Falls, Musselshell and others. As these lakes grew, the water in them would often spill over into adjacent local divides, creating now-abandoned channels and coulees, including the Shonkin Sag, of 160 km long. As the glaciers retreated, the Missouri flowed in a new course along the south side of the Bearpaws, with the lower Milk River tributary taking over the initial main channel.

The Missouri's nickname, the Big Muddy, was inspired by the enormous loads of sediment or silt it carries, some of the largest of any North American river. pre-development, the river carried some 193-290 million tons per year. Construction of dams and levees has drastically reduced this to 18-23 million tons per year today. Much of this sediment is bypassed from the river floodplain, also called the meander belt; every time the river changed course, it would erode tons of dirt and rocks from its banks. However, damming and channeling the river has now prevented it from reaching its natural sources of sediment along most of its course. Reservoirs along the Missouri capture an estimated 32.9 million tons of sediment each year. Despite this, the river still carries more than half of the total sediment that flows into the Gulf of Mexico; The Mississippi Delta, formed by sedimentary deposits at the mouth of the Mississippi, is made up largely of sediments carried by the Missouri.

History

First Nations

Archaeological evidence, especially in Missouri, suggests that man made his first presence in the Missouri Basin between 10,000−12,000 years ago, at the end of the Pleistocene. During the end of the last glacial period, a great human migration began, traveling across the Bering land bridge from Eurasia into the entire American continent. Since they would travel slowly over centuries, the Missouri River would form one of their main migration routes. Most settled in the Ohio Valley and lower Mississippi River valley, but many, including the Mound Builders, remained along the Missouri, becoming the ancestors of later Great Plains native peoples.

Native Americans living along the Missouri had access to sufficient food, water, and shelter. Many migratory animals inhabited the plains at that time, providing them with meat, clothing, and other items of daily use. There were also large riparian areas in the river's floodplains that provided them with natural herbs and staple foods. There are no written records of the tribes and peoples of pre-European times, as they did not use writing. According to the explorers' writings, the most important tribes on the Missouri were the Otoes, Missouri, Omahas, Poncas, Brulés, Lakotas, Sioux, Arikaras, Hidatsas, Mandans, Assiniboines, Gros Ventres, and Blackfeet.

The natives used the Missouri, at least to some degree, as a trade and transportation route. In addition, the river and its tributaries formed the tribal borders. The native lifestyle was largely centered around a semi-nomadic culture; many tribes had different summer and winter camps. However, the center of native wealth and trade along the Missouri was in the Dakotas region in its great southern bend. A large group of stockade towns of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara stood on the bluffs. and river islands and were home to thousands of people, and later served as markets and trading posts used by early French and British explorers and fur traders. After the introduction of the horse to the Missouri River tribes, possibly of feral populations introduced by Europeans, the way of life of the natives changed substantially. The use of the horse allowed great distances to be traveled, and therefore facilitated hunting, communication, and trade.

At one time, tens of millions of American bison (commonly called buffalo), a keystone species of the Great Plains and Ohio Valley, roamed the plains of the Missouri Basin. Natives in the basin relied heavily on bison as a food source, with their hides and bones being used to create other household items. Over time, the species came to benefit from the periodic controlled burns that native peoples set on the prairies surrounding the Missouri to clear old and dead brush. The region's large bison population led to the termination of the great bison belt, an area of rich annual grasslands that stretched from Alaska to Mexico along the eastern flank of the Continental Divide. after the arrival of the Europeans, both the bison and the Native Americans themselves experienced rapid population declines. Hunting wiped out the bison populations east of the Mississippi River by 1833 and reduced numbers in the Missouri basin to about mere hundreds. Foreign diseases such as smallpox swept through the region, decimating the native populations. Left without their main source of livelihood, many of the surviving native communities merged into resettlement zones and reserves.

Early Western Explorers

In May 1673, French explorers Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette left the Lake Huron settlement of St. Ignace and headed down the Wisconsin and then the Mississippi Rivers to reach the Pacific Ocean. In late June, Jolliet and Marquette became the first documented European discoverers of the Missouri River, which according to their journals was in full flood. "I never saw anything more terrifying," Jolliet wrote, "a tangle of entire trees from the mouth of the Pekistanoui [Missouri] with such impetus that one could not try to cross it without great danger. The commotion was such that the water turned muddy from it and could not be made clear." They recorded Pekitanoui or Pekistanoui as the native name for the Missouri. However, the party never explored the Missouri beyond its mouth, nor did they remain in the area. Furthermore, they later learned that the Mississippi flowed into the Gulf of Mexico and not into the Pacific as they had originally assumed; the expedition turned about 710 km before the Gulf, at the confluence of the Arkansas River with the Mississippi.

In 1682, France expanded its territorial claims in North America to include land on the west side of the Mississippi River, which included the lower Missouri. However, Missouri itself remained formally unexplored until Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont, leading an expedition in 1714, traced it at least to the mouth of the Platte River. It is not clear exactly how far Bourgmont traveled beyond there; he described blonde mandans in his journals, so it likely reached their villages in present-day North Dakota. Later that year, Bourgmont published The Route To Be Taken To Ascend The Missouri River [The Route to be Taken to Ascend the Missouri River], the first known document to use the name "Missouri River"; Many of the names Veniard gave to the tributaries, mostly for the native tribes that lived along them, are still in use today. The expedition's discoveries were eventually reflected on by cartographer Guillaume Delisle, who used the information to create a map of lower Missouri. In 1718, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville petitioned that the French government award Bourgmont the Cross of St. Louis for his "exceptional service to France".

Bourgmont had, in fact, been in trouble with the French colonial authorities since 1706, when he resigned as commander of Fort Detroit after mishandling an attack by the Ottawas that left thirty-one dead. His reputation was bolstered in 1720 when Pawnees—who had earlier befriended Bourgmont—massacred the Spanish Villasur Expedition near present-day Columbus, Nebraska on the Missouri River, temporarily ending the Spanish invasion of French Louisiana. Bourgmont established Fort Orleans, the first European settlement of any kind on the Missouri River near present-day Brunswick, Missouri, in 1723. The following year Bourgmont led an expedition to gain Comanche support against the Spanish, who continued to show interest in gaining control of the Missouri. In 1725 Bourgmont took the chiefs of several Missouri River tribes to visit France. There he was elevated to the rank of nobility and did not accompany the chiefs back to North America. Fort Orleans was abandoned or its small contingent massacred by Native Americans in 1726.

The French and Indian War broke out when territorial disputes between France and Great Britain in North America came to a head in 1754. In 1763 France was defeated by the much greater force of the British army and was forced into the Treaty of Paris (1763) to cede its Canadian possessions to the English and Louisiana to the Spanish, affecting most of its colonial possessions in North America.

Initially, the Spanish did not explore the Missouri extensively, leaving French traders to continue their activities under license. This ended, however, after news came back from a Jacques D'Eglise expedition in the 1790s that the British Hudson's Bay Company was raiding the upper Missouri River. In 1795 the Spanish guaranteed the "Company of Discoverers and Explorers of the Missouri", popularly known as the "Company of the Missouri", and offered a reward for the first person to reach the Pacific Ocean through the Missouri. In 1794 and 1795 expeditions led by Jean Baptiste Truteau and Antoine Simon Lecuyer de la Jonchšre failed even to reach as far north as Mandan villages in central North Dakota.

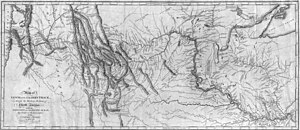

Arguably the most successful of the Missouri Company expeditions was that of James MacKay and John Evans. The two continued along the Missouri, establishing Fort Charles about 20 miles south of present-day Sioux City as a winter camp in 1795. In the Mandan villages in North Dakota, they drove out several British traders, and while talking with the natives they identified the location of the Yellowstone River, which was called Roche Jaune (« Yellow Rock") by the French. Although MacKay and Evans were unable to meet their original goal of reaching the Pacific, they did create the first accurate map of the upper Missouri River.

In 1795, the young United States and Spain signed the Treaty of Pinckney, which recognized American rights to navigate the Mississippi River and bring goods for export to New Orleans. Three years later, Spain revoked the treaty and in In 1800, he secretly returned Louisiana to Napoleonic France in the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso. This transfer was so secret that the Spanish continued to administer the territory. In 1801, Spain restored the rights to use the Mississippi and New Orleans to the United States.

Fearing such interruptions could occur again, President Thomas Jefferson proposed that France buy the port of New Orleans for $10 million. Napoleon, faced with a debt crisis, surprisingly offered him all of Louisiana, including the Missouri River, for $15 million, which came out to less than 3 cents an acre. The agreement was signed in 1803, doubling the size of the United States with the acquisition of the Louisiana Territory. In 1803, Jefferson instructed Meriwether Lewis to explore the Missouri and search for a waterway to the Pacific Ocean. By this time, the Columbia River system, which empties into the Pacific, had been found to have a latitude similar to that of the headwaters of the Missouri River, and it was widely believed that a connection, or short portage, existed between the two. However, Spain opposed the takeover, claiming that they had never formally returned Louisiana to the French. Spanish authorities warned Lewis against making the trip and forbade him from seeing the map of the MacKay and Evans expeditions of the Missouri, although Lewis eventually gained access to it.

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark began their famous expedition in 1804 with a group of thirty-three people in three boats. Although they became the first Westerners to travel the entire length of the Missouri and reach the Pacific via the Columbia River, they found no trace of the Northwest Passage. The maps made by Lewis and Clark, especially those of the Pacific Northwest region, provided the foundation for future explorers and emigrants. They also negotiated relationships with many native tribes they encountered and wrote extensive reports on the climate, ecology, and eology of the regions they passed through. Many current names for the upper Missouri basin's landforms originated from that expedition.

American Frontier

Fur trade

In the early 19th century, fur hunters and trappers entered the far north of the Missouri basin with hoping to find populations of beaver and river otter, whose fur sales led to the thriving North American fur trade. They came from many different places, some from the Canadian fur corporations in Hudson Bay, some from the Pacific Northwest (see also: maritime fur trade), and some from the American Midwest. Most did not stay in the area for long, failing to find any significant resources.

The first enthusiastic reports that there was indeed a country rich with animals to be hunted came in 1806 when Meriwether Lewis and William Clark returned from their two-year expedition. His posts described rich lands with thousands of bison, beavers, and river otters; and also an abundant population of sea otters on the Pacific Northwest coast. In 1807, fur trader Manuel Lisa organized an expedition that would lead to the explosive growth of the fur trade in the Upper Missouri regions. Lisa and his party traveled up the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers, trading with local native tribes, trading manufactured goods for furs. They established a fort at the confluence of the Yellowstone Rivers and one of its tributaries, the Bighorn River, in southern present-day Montana. Although the business started out small, it quickly grew into a thriving business.

In the fall of 1807, Lisa's men began construction of Fort Raymond, which sat on a bluff overlooking the confluence of the Yellowstone and Bighorn rivers. The fort would serve primarily as a trading post for bartering with the natives for furs. This method was different from the fur trade in the Pacific Northwest, which involved hunters hired by various fur companies, primarily the Bay Company. of Hudson and the North West Company. Fort Raymond was later succeeded by Fort Lisa at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone in North Dakota; a second fort, also named Fort Lisa, was built down the Missouri River in Nebraska. In 1809 the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company was founded, with Lisa, William Clark, and Pierre Choteau, among others, as partners. In 1828, the American Fur Company founded Fort Union at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers. Fort Union will eventually be the main site of the upper Missouri fur trade.

Fur trapping in the early 19th century took place in almost the entire Rocky Mountains, on both sides, eastern and western. Hunters and trappers from the Hudson's Bay Company, the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company, the American Fur Company, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, the North West Company, and other independent brigades worked the thousands of creeks. of the Missouri Basin, as well as the neighboring river systems of the Columbia, Colorado, Arkansas, and Saskatchewan. During this period, trappers, also called mountain men, blazed trails through these still untouched regions, which would later become the roads and highways along which pioneers and settlers would travel west. The transport of the thousands of beaver skins also required the use of boats, this being one of the causes for fluvial transport in the Missouri to begin.

As the 1830s ended, the fur industry began to slowly decline as silk replaced beaver pelts as the desired item of clothing. By this time, too, the stream beaver population in the Rocky Mountains had been decimated by intense hunting. In addition, frequent native attacks on trading posts made business dangerous for employees of fur companies. In some regions the industry continued well into the 1840s, but in others, such as the Platte River Valley, declining beaver populations contributed to an early death. The fur trade eventually died out in the Great Plains in 1850, with the main center of industry shifting to the Mississippi Valley and central Canada. Despite the demise of that once thriving trade, however, his legacy allowed for the opening up of the American West and the proliferation of settlers, farmers, ranchers, adventurers, and businessmen who took their place.

Settlements and Pioneers

The Missouri River roughly defined the American frontier in the 19th century, mostly downstream of Kansas City, where the river makes an eastern turn heading into the heart of the state of Missouri. The major roads for the opening of the Wild West all have their starting points on the river, including the California, Mormon, Oregon, and Santa Fe routes. The Pony Express's first westbound outpost was a ferry across the Missouri in St. Joseph, Missouri. Similarly, most emigrants reached the eastern terminus of the First Transcontinental Railroad via a ferry that crossed the Missouri between Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Omaha. The Hannibal Bridge was the first bridge to span the Missouri River in 1869, and its location was a major reason Kansas City (MO) became the largest city on the river upstream of its mouth in St. Louis.

Following the ideal of Manifest Destiny, more than 500,000 people left the waterfront city of Independence, MO, for their various destinations in the American West from the 1830s to the 1860s. They had many reasons for embarking on that grueling year-long journey—economic crises and subsequent gold rushes, such as the California Gold Rush, for example. Most followed a route that took them up the Missouri to Omaha (NE), where they would have followed the Great Platte River Highway, which followed the Platte River flowing east from the Rocky Mountains in Wyoming and Colorado. across the Great Plains. An early expedition led by Robert Stuart (1812-1813) proved that the Platte was impossible to navigate with the canoes they used, not to mention the great wheel steamers and steamships that would later ply the Missouri in increasing numbers. One explorer noted that the Platte was "too thick to drink, too thin to plough." However, the Platte provided an abundant and reliable source of water for pioneers heading west. Covered wagons, popularly known as "prairie schooners", were the main means of transportation until the start of regular river boat service in the 1850s.

During the 1860s, gold rushes in Montana, Colorado, Wyoming, and northern Utah brought another wave of aspirants to the region. Although some cargo was transported overland, most transport to and from the gold fields was carried out via the Missouri and Kansas rivers, as well as the Snake River in western Wyoming and the Bear River in Utah. Idaho and Wyoming. It is estimated that of all the passengers and cargo transported from the Midwest to Montana, more than 80% were transported by ship, a journey that took 150 days in the upstream direction. A more direct route west into Colorado stretched along the Kansas River and its tributary the Republican River, as well as a couple of small streams in Colorado, the Big Sandy and the South Platte River, to near Denver. The gold rushes precipitated the decline of the Bozeman Trail as a popular emigration route, as it passed through land belonging to the often hostile Native Americans. Safer roads to the Great Salt Lake near Corinne, Utah (UT) were opened during the gold rush period, leading to large-scale settlement in the Rocky Mountain region and eastern Great Basin.

As settlers expanded their holdings on the Great Plains, they ran into land conflicts with Native American tribes. This led to frequent raids, massacres, and armed conflict, leading the federal government to sign multiple treaties with the plains tribes, which generally involved establishing borders and land reservations for the natives. Like many other treaties between Native Americans and the US, they were soon broken, leading to major wars. More than 1,000 battles, large and small, were fought between the US military and the natives before the tribes were driven off their land and confined to reservations.

Conflicts between natives and settlers during the opening of the Bozeman Trail in the Dakotas, Wyoming, and Montana led to the Red Cloud War, in which the Lakotas and Cheyennes fought the US Army. The fighting ended in complete victory for the Native Americans. Native Americans without white intervention.

The Missouri River was also an important landmark as it divided northeastern Kansas from western Missouri. Slaving forces from Missouri would cross the river into Kansas and wreak havoc during Bleeding Kansas, leading to continued tension and hostility, still existing today, between Kansas and Missouri. Another significant military conflict on the Missouri River during this period was the 1861 Battle of Boonville, which did not affect the Native Americans, but rather was a turning point in the American Civil War that allowed the Union to take control of transportation. on the river, discouraging the state of Missouri from joining the Confederacy.

However, the peace and freedom of the Native Americans did not last long. The Great Sioux War of 1876-77 broke out when American miners discovered gold in the Black Hills of western South Dakota and eastern Wyoming. These lands were originally established as a reservation for native use by the Treaty of Fort Laramie. When settlers entered these lands they were attacked by the natives. American troops were sent to the area to protect the miners, and drive the natives out of the new settlements. During that bloody period, both the natives and the US military won victories in major battles, resulting in the loss of nearly a thousand lives. The war ultimately ended in an American victory, and the Black Hills were open to colonization. The natives of the region were moved to new reservations in Wyoming and southeastern Montana.

The era of dam construction

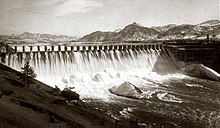

Late 19th century and early XX, a large number of dams were built along the Missouri, transforming 35% of the river into a chain of reservoirs. The development of the river was stimulated by the increasing demand for electricity in the rural areas of the northwestern basin, and also to avoid the floods and droughts that rapidly devastated the growing agricultural and urban areas in the lower Missouri. Starting in the 1890s, small hydroelectric projects, privately owned, were tackled. but the large damming and flood control dams that characterize the middle reaches of the river today were not built until the 1950s.

Between 1890 and 1940, five dams were built in the vicinity of Great Falls (MT) to generate power from the Great Falls of the Missouri, a chain of giant waterfalls formed by the river as it passed through western Montana. Black Eagle Dam, built in 1891 at Black Eagle Falls, was the first dam on the Missouri. Replaced in 1926 with a more modern structure, the dam was little more than a small weir atop Black Eagle Falls, diverting part of the Missouri's flow to the Black Eagle Power Plant. The largest of the five dams, Ryan Dam, was built in 1913. The dam sits just above 90 feet of Great Falls, the largest waterfall on the Missouri.

In the same period, several private companies—mainly the Montana Power Company—began to develop the Missouri River for power generation above Great Falls and below Helena (MT). In 1898, a small trickle dam, the second dam on the Missouri, was completed near the present site of Canyon Ferry Dam. This rock-filled wooden dam generated 7.5 megawatts of electricity for Helena and the surrounding area. The nearby Hauser Dam, a steel dam, was completed in 1907 but failed in 1908 due to structural deficiencies, causing catastrophic flooding. downriver to past Craig (MO). In Great Falls, a section of the Black Eagle Dam had to be dynamited to save nearby factories from flooding. Hauser was rebuilt in 1910 as a concrete gravity structure and is still in use today.

The Holter Dam, about 72 km downstream of Helena, was the third hydroelectric dam built on this stretch of the Missouri River. In 1918 by the Montana Power Company and the United Missouri River Power Company, its reservoir flooded the Gates of the Mountains, a limestone canyon that Meriwether Lewis described as "the most remarkable cliffs we have yet seen...the turrets and rocks that stand out in many places seem ready to come down on us." In 1949, the U.S. The Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) broke ground on the modern Canyon Ferry Dam for flood control in the Great Falls area. In 1954, water from Canyon Ferry Lake submerged the old 1898 dam, whose powerhouse still stands underwater near 1.5 miles waters. above the current dam.

[Misuri Temperament was] uncertain as the actions of a jury or the mood of a woman. ("[The Missouri's temperament was] uncertain as the actions of a jury or the state of a woman's mind.") -Sioux City Register, March 28, 1868 |

The Missouri basin suffered a series of catastrophic floods around the turn of the XX century, most notably in 1844, 1881, and 1926–1927. In 1940, as part of the Great Depression-era New Deal, the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE)) completed the Fort Peck Dam in Montana. The construction of this massive public works project provided employment to more than 50,000 workers during the Great Depression and was an important step in flood control in the middle Lower Missouri River. However, Fort Peck only controls runoff for 11% of the Missouri River watersheds, and had little effect on a severe snowmelt flood that struck the lower Missouri River three years later. This event was especially destructive, submerging manufacturing plants in Omaha and Kansas City, significantly delaying shipments of military supplies in World War II.

Flood damage to the Mississippi-Missouri River system was one of the primary reasons the United States Congress passed the Flood Control Act of 1944 (Flood Control Act of 1944), opening the way for the Corps of Engineers to develop the Missouri on a massive scale. i>, or Pick–Sloan Plan), which was a combination of two very different proposals: the Pick plan, with an emphasis on flood control and hydroelectric power, proposed the construction of large dams of storage along the main course of the Missouri; and the Sloan plan, which emphasized local irrigation development and included provisions for approximately 85 smaller dams on tributaries.

In the early stages of the Pick–Sloan development, tentative plans were made to build a low dam on the Missouri at Riverdale, North Dakota, and 27 smaller dams on the Yellowstone River and its tributaries. This was opposed by the inhabitants of the Yellowstone Basin, and eventually the USBR proposed another solution: greatly raise the height of the proposed Riverdale dam, now Garrison Dam, thus replacing the storage provided by the Yellowstone dams. Because of this decision, the Yellowstone is now the longest free-flowing river in the contiguous United States. Construction began in the 1950s on the five mainstem reservoirs—Garrison, Oahe, Big Bend, Fort Randall and Gavins Point – proposed under the Pick–Sloan Plan. Along with Fort Peck, which was integrated as a unit of the Pick–Sloan Plan in the 1940s, these dams now form what is known as the "Plan System." Missouri River Mainstem System» (Missouri River Mainstem System).

The six dams in the Mainstem System, primarily Fort Peck, Garrison, and Oahe, are among the world's largest dams by volume; its extensive reservoirs are also among the largest in the nation. Damping up to 91.4km³ in total, the six reservoirs can store the river's total flow of more than three years as measured downstream of Gavins Point, the lower dam. This enormous capacity makes it the largest storage system in the United States and one of the largest in North America. In addition to storing water from irrigation, the system also includes an annual flood control reserve of 20.1 km³. Power plants on the mainstem generate about 9, 3 million kWh per year, equal to a steady output of nearly 1,100 megawatts. Together with about 100 smaller dams built on tributaries of the Missouri, Primarily on the Bighorn, Platte, Kansas, and Osage rivers, the system provides irrigation water to about 19,000 km² of land.

The folded table to the right lists the statistics for the fifteen dams on the Missouri River, ordered downstream. Many of the run-of-the-river dams (marked in yellow) require very small reservoirs which may or may not have a name; those not named are left blank. All the dams are in the upper half of the river, above the town of Sioux City; the lower part of the river is unbroken due to its long-standing use as a navigation channel.

Navigation

[The freight on the Missouri River] never reached its expectations. Even in the best of circumstances, it was never a great industry. ("[Missouri River shipping] never achieved its expectations. Even under the very best of circumstances, it was never a huge industry.") ~ Richard Opper, former executive director of the Missouri River Basin Associationr |

Boat travel on the Missouri began with Native American wood-frame canoes and bull boats, which were used for thousands of years before the introduction of large river boats in the colonization of the Missouri Great Plains. The first steamboat on the Missouri was the Independence, which began traveling between St. Louis and Keytesville, Missouri around 1819. By the 1830s, steamships were operating regularly for large mail and freight between the cities of Kansas City and St. Louis, and many traveled even farther up the river. A handful, such as the Western Engineer and the Yellowstone, were able to travel up the Missouri as far east as Montana.

During the 19th century, at the time of the fur trade, steamboats and keelboats began to traversed nearly the entire length of the Missouri from the Montana escarpments of the Missouri Breaks to the mouth, carrying beaver and bison pelts to and from the areas that trappers frequented. This led to the development of the Missouri River Mackinaw boat, who specialized in the transport of skins. Since these vessels could only travel downstream, they were dismantled and sold for lumber upon arrival in San Luis.

Fluvial transport increased in the 1850s with the multiple transport in artisanal boats of the pioneers, emigrants and miners; many of these trips were from St. Louis or Independence to near Omaha. There most of these people set out overland along the long but shallow and navigable Platte River, which was described by pioneers as "a mile wide and an inch deep" and "the most magnificent and worthless of rivers." Steamships peaked in 1858, when more than 130 ships, and many smaller vessels, operated full-time on the Missouri. Many of the earliest vessels were built on the Ohio River, before being transferred to Missouri. Paddle steamers were preferred to the large steamboats that were more widely used on the Mississippi and Ohio, due to their greater maneuverability.

The success of the industry, however, did not guarantee safety. In the first decades before the river's flow was controlled, its rises and falls and the enormous amounts of sediment, which prevented a clear view of the bottom, destroyed some 300 boats. Due to the dangers of navigation on the Missouri River, the average lifespan of ships was short, only about four years. The development of the Transcontinental Railroad and the Northern Pacific marked the beginning of the end of the steamboat trade in the Missouri. Outcompeted by trains, the number of ships slowly dwindled, until almost none remained by the 1890s. The transport of agricultural and mining products by barge, however, experienced a renaissance at the turn of the century XX.

Passage to Sioux City

Since the turn of the 20th century, the Missouri River has been extensively conditioned to allow river transportation and nearly 32% of the river flows operated full-time in the Missouri through artificially straightened channels. In 1912, the USACE was authorized to maintain the Missouri at a depth of 1.8 m (six feet) from the Port of Kansas City to the mouth, a distance of 592 km. This was accomplished by building levees and wing dams to direct the flow of the river in a straight and narrow channel to avoid siltation. In 1925, the USACE began a project to widen the river's navigation channel to 61 m (200 ft); two years later, dredging of a deep-water channel from Kansas City to Sioux City began. These modifications have reduced the length of the river from about 4090 km at the end of the century XIX to present 3767 km.

Damming the Missouri under the Pick-Sloan Plan in the mid-20th century XX was the final step in aid to navigation. The large reservoirs of the Mainstem System helped provide a reliable flow to maintain the navigation channel year-round, and were able to stem most of the river's annual floods. However, the Missouri's high-low cycles—in particularly the prolonged drought of the early 21st century of the Missouri Basin and the historic floods of 1993 and 2011— they are difficult to control even for the large reservoirs of the Mainstem System.

In 1945, the USACE began the "Missouri River Bank Stabilization and Navigation Project" (Missouri River Bank Stabilization and Navigation Project), which would permanently increase the navigation channel of the river to a width of 91 m (300 ft) and a depth of 2.7 m (nine feet). During these works that continue to this day, the 1183 km of the navigation channel from Sioux City to San Luis has been controlled by the construction of rock dikes to direct river flow and removing sediment, sealing and cutting meanders and side channels, and dredging the river bed. However, the Missouri has often resisted USACE efforts to control its depth. In 2006, several US Coast Guard ships ran aground in the Missouri because the shipping channel had been severely silted. The USACE was blamed for not maintaining the minimum depth in the channel.

In 1929, the Missouri River Navigation Commission estimated that the total amount of merchandise shipped down the river annually would be about 15 million tons (13.6 million metric tons), providing a broad consensus for the creation of a navigation channel. However, river traffic since then has been much less than expected, and shipments of raw materials, including products, manufactured goods, lumber, and oil, averaged only 683,000 tons (616,000 tons) per year from 1994 to 2006.

By tonnage of material transported, the state of Missouri is by far the largest consumer, accounting for 83% of the river's traffic, while Kansas has 12%, Nebraska 3% and Iowa 2%. Nearly all barge traffic ships sand and gravel dredged from the 800 km in lower Missouri; the remaining part of the shipping channel now sees little to no use by commercial vessels.

Declining traffic

The tonnage of goods shipped by barge on the Missouri River has seen a significant decline from the 1960s to the present. In the 1960s, the USACE predicted an increase of 10,800,000 tons/year by 2000, but instead the opposite has occurred. The amount of goods fell from 3,000,000 t in 1977 to just 1,180,000 t in 2000. One of the largest declines has been in agricultural products, especially wheat. Part of the reason is that the irrigated land along the Missouri has only been developed to a fraction of its potential. In 2006, barges on the Missouri carried only 180 000 t of products which is equal to the amount of freight traffic per day on the Mississippi.

Drought conditions in the 21st century and competition from other modes of transportation—mainly rail—are the main reason for the decline in river traffic on the Missouri. The USACE's failure to consistently maintain the shipping channel has also hampered the industry. Efforts are currently underway to revive the river transportation industry on the Missouri, due to the efficiency and cheapness of transporting agricultural products, and the saturation in alternative transportation routes. Solutions such as the expansion of the navigation channel and the release of more water from the reservoirs during the peak of the navigation season are being considered. Drought conditions suffered in 2010, in which one 301,000 t shipped on the Missouri, marking the first significant increase in shipments since 2000. However, flooding in 2011 closed a record for ship traffic on the river.

There are no locks or dams on the lower Missouri River, but there are plenty of dams that keep Jettie's on the river and make it harder for barges to navigate. In contrast, the Upper Mississippi has 28 locks and dams and an average 63,100,000 t of cargo per year from 2008 to 2011, and which is closed 5 months of the year. Whereas the Missouri River only carried just over 300,000 t in 2010 and it was a rising year.

Ecology

Natural history

Historically, the thousands of square miles of the Missouri River floodplain supported a wide variety of plant and animal species. Biodiversity in general increased going downstream from the cool, subalpine headwaters in Montana, toward the temperate, humid climate of Missouri. Today, the river's riparian zone consists primarily of cottonwood, willow, and sycamore, with other types of trees including maple and ash. Average tree heights generally increase as you move a limited distance from the riverbank, since the land adjacent to the river is vulnerable to soil erosion during floods. Due to high concentrations of sediment, the Missouri does not support many aquatic invertebrates. However, the basin is home to about 300 species of birds and 150 species of fish, some of which are endangered, such as the pale sturgeon. The aquatic and riparian habitats of the Missouri also support several species of mammals, such as bison, river otters, beavers, muskrats, and raccoons.

The World Wide Fund for Nature divides the Missouri basin into three freshwater ecoregions: Upper Missouri (or Upper Missouri, Upper Missour), Lower Missouri (Lower Missouri), i>) and the Central Prairie (Central Prairie). Upper Missouri, which roughly encompasses the area within Montana, Wyoming, southern Alberta and Saskatchewan, and North Dakota, consists primarily of semi-arid, steppe-shrub grassland with little biodiversity due to the Ice Age. Ice. There are no known endemic species within the region. Except for the headwaters in the Rockies, there is little precipitation in this part of the basin. The Middle Missouri ecoregion, which extends through Colorado, southwestern Minnesota, northern Kansas, Nebraska, and parts of Wyoming and Iowa, has higher rainfall and is characterized by temperate forests and grasslands. Plant life is most diverse in the Middle Missouri, which is also home to about twice as many animal species. Finally, the Central Prairie ecoregion is located in the lower Missouri, encompassing all or parts of Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma and Arkansas. Despite large seasonal fluctuations in temperature, this region has the highest plant and animal diversity of the three. Thirteen species of crayfish are endemic to Lower Missouri.

Human Impact

Since the beginning of river trade and industrial development in the 1800s, the Missouri has been severely polluted and its water quality degraded by human activity. Most of the river's floodplain habitat has disappeared, replaced by irrigated agricultural land. Floodplain development has resulted in increasing numbers of people and infrastructure within areas at high risk of flooding. Levees have been built along more than a third of the river in order to keep floods within the channel, but as a consequence, the current is faster with a consequent increase in peak flows in low-lying areas. Fertilizer runoff, which causes elevated levels of nitrogen and other nutrients, is a major problem along the Missouri, especially in the states of Iowa and Missouri. This form of pollution also greatly affects the rivers of the Upper Mississippi, Illinois, and Ohio. Low oxygen levels in rivers and in the large dead zone of the Gulf of Mexico at the end of the Mississippi Delta is the result of high nutrient concentrations in the Missouri and other tributaries of the Mississippi.

The channelization of the Lower Missouri has made the river narrower, deeper, and less accessible to riparian flora and fauna. Numerous dams and riparian stabilization projects have been built to facilitate the conversion of 1,200 km² of Missouri River floodplain to agricultural land. Channel control has greatly reduced the volume of sediment carried downstream by the river, eliminating critical habitat for fish, birds, and amphibians. At the turn of the century XXI, declining populations of native species prompted the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, or USACE, to issue a biological opinion recommending restoration of riverine habitats for federally endangered species of birds and fish.

USACE began work on ecosystem restoration projects in the lower Missouri in the early 21st century. Due to the low utilization of the navigation channel on the lower Missouri maintained by the USACE, it is now considered feasible to remove some of the dams, levees, and dams that constrict the river's flow, allowing it to restore its banks to the natural shape. As of 2001, there was 350 km² of riparian floodplain undergoing active restoration.

Restoration projects have remobilized some of the sediments that had been trapped behind riparian stabilization structures, raising concerns about exacerbated nutrients and sediment contamination locally and downstream in the northern Gulf of Mexico. A 2010 United States National Research Council report evaluated the role of sediments in the Missouri, weighing current habitat restoration strategies and some alternative ways to manage such sediments. The report found it necessary to better understand sedimentation processes in the Missouri, including the creation of a "sediment budget"—an accounting of sediment transport, erosion, and deposition volumes along the entire length of the river—that would provide a baseline for projects to improve water quality standards and to protect endangered species.

Tourism and recreational use

With more than 3,900 km² of open water, the six reservoirs of the main Missouri system provide some of the major recreational areas within the watershed. Visitation has increased from 10 million visitor-hours in the 1960s to more than 60 million visitor-hours in 1990. The development of visitor services was spurred by the California Recreation Project Act. Federal Water Project Recreation Act 1965 (Federal Water Project Recreation Act ), which required the USACE to construct and maintain boat ramps, campgrounds, and other public facilities along major reservoirs. Recreational use of Missouri River reservoirs contribute $85-100 million to the regional economy each year.

The Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, some 6000 km in length, follows most of the Missouri from its mouth to its source, following part of the route of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Extending from Wood River, Illinois, in the east, to Astoria, Oregon, in the west, it also follows sections of the Mississippi and Columbia rivers. Running through eleven states, the trail is managed by various federal and state agencies, passing through some 100 historic sites, including archaeological sites such as the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site.

Some parts of the river itself have been designated for recreational or preservation use. The Missouri National Recreational River consists of portions of the Missouri downstream of the Fort Randall and Gavins Point dams totaling 158 km. These sections present islands, meanders, sand bars, underwater rocks, riffles, snags (dead trees), and other formerly common features in the lower part of the river that have now disappeared under the reservoirs or have been destroyed by channeling. Forty-five steamboat wrecks are scattered along these stretches of the river.

Downstream from Great Falls, Montana, some 240 km of the river courses through a series of canyons and lowlands known as the Missouri Breaks. Designated a National Wild and Scenic River in 1976, this portion of the river flows within Upper Missouri Breaks National Monument (Upper Missouri Breaks National Monument), an area of 1520 km² of preserve comprising cliffs, deep ravines, barren plains, badlands, archeological sites and whitewater rapids in Missouri itself. The preserve includes a wide variety of plant and animal life; Leisure activities include canoeing, rafting, hiking, and wildlife viewing.

In north central Montana, about 4,500 km² across more than 201 km of the Missouri River, centered around Fort Peck Lake, comprise the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge. The wildlife refuge consists of an ecosystem native to the northern Greater Plains that has not been affected by human development, except for the construction of the Fort Peck Dam. Although there are few designated trails, the preserve is open for hiking and camping.

Some national parks in the United States, such as Glacier National Park, Rocky Mountain National Park, Yellowstone National Park, and Badlands National Park are in the Missouri basin. Stretches of other rivers in the basin are set aside for preservation and recreational use, most notably the Niobrara National Scenic River, which is a protected stretch of 122 km of the Niobrara River, one of the Missouri's longest tributaries. The Missouri flows through, or past, several National Historic Landmarks, including the Three Forks of the Missouri, Fort Benton, Montana, Big Hidatsa Village Site, Fort Atkinson, Nebraska and Arrow Rock Historic District.

Tributaries

The Missouri River has many tributaries, the most important being those listed in the following table. The tributaries are ordered geographically, following the river from its source to its mouth.

Contenido relacionado

Vigo

Sepulveda

Sonora