Misogyny

misogyny (from the Greek μισογυνία; misos and gyne respectively: 'hatred of women') It is the aversion, contempt or hatred towards women. It is considered the sexist counterpart of misandry. Misogyny can manifest itself in a variety of ways, including denigration, rejection, discrimination, and violence against women.

Definition

According to sociologist Allan G. Johnson: "[...] is at the heart of sexist prejudices and ideologies and, as such, is one of the bases for the oppression of women in male dominated societies. Misogyny manifests itself in different ways, from jokes to pornography, violence and the feeling of hatred towards their own body that women are instructed to feel."

Sociologist Michael Flood of the University of Wollongong defines misogyny as hatred of women and notes:

Although more common in men, misogyny is also practiced by women against other women or even towards themselves. Misogyny works as a system of ideologies or beliefs that have accompanied patriarchal societies or dominated by men for thousands of years and continues to place women in sub-baltern positions with little possibility of power or decision-making. [...] Aristotle argued that women exist as a deformity of nature or as imperfect men [...]. Thus, the women of the West have internalized their role as the scapegoats of society, influenced in the twenty-first century by the objection of women in the media, through the culturally hated self-despence and fixing to plastic surgery, anorexia and bulimia.

Dictionaries define misogyny as "hatred of women" or "hatred, aversion or distrust of women". In 2012, responding to events that occurred in the Australian Parliament, the Macquarie Dictionary (documenting Australian English and New Zealand English) expands the definition to include not only hatred of women but also adds "entrenched prejudice against women". The inverse of misogyny is misandry, hatred or aversion to men; The antonym of misogyny is phylogyny, the love or liking of women.

Classical Greece

In his book The City of Socrates: An Introduction to Classical Athens, J.W. Roberts argues that misogyny is even older than tragedy and comedy in Greek literature, going back at least as far as Hesiod.

The word misogyny comes from the Greek word misogunia (μισογυνία), which is found in two passages.

Semonides of Amorgos already composed some famous iambs against bad women, also comparing the good ones with industrious and honey bees. But the oldest and most complete is found in the moral treatise On Marriage (c. 150 BC) written by the Stoic philosopher Antipater of Tarsus. Antipater argues that marriage is the basis of the State, and considers that it is based on a divine (polytheistic) decree. Antipater uses the word misogunia to describe the writings of Euripides —tēn misogunian en tō graphein (τὴν μισογυνίαν ἐν τῷ γράφειν "misogyny in writing"). However, Antipater does not mention where he finds misogyny in Euripides' writing, merely stating his belief that even a man who hates women (Euripides) praises wives, and concludes his argument with the importance of marriage: & #34;It's really heroic".

The misogynistic image of Euripides can also be found in the Scholars' Banquet, where Athenaeus includes one of the diners quoting Jerome of Cardia, who confirms that his reputation was common knowledge, while offering comments to Sophocles on the matter at hand:

The poet Eurípides, too, was addicted to women: at all events "Hieronymus", in his "Historical Comments", says the following: "When someone told Sófocles that Eurípides was a hatwoman, 'Maybe it is,' he said, 'in his tragedies, but in bed he was very fond of women.'

Even with Euripides' fame, Antipater is not the only writer to express appreciation for women in his writings. Katherine Henderson and Barbara McManus claim that he "shows more empathy for women than any other ancient writer", citing the "relatively modern criticisms" to support his claim.

Another example of the use of the Greek word is given by Chrysippus of Solos in a fragment of On Affections quoted by Galen in Hippocrates Affections. Here, misogyny is the first of a short list of three "disaffected"—women (misogunian), wine (misoinian, μισοινίαν), and humanity (misanthrōpian, μισανθρωπίαν). Chrysippus' point is more abstract than Antipater's. Galen cites the passage as an example of an opinion contrary to his own; what is clear is that he groups hatred of women together with hatred of humanity in general, and even with hatred of wine: "It was an imperative opinion in his day that wine strengthens the body and mind. soul alike." So Chrysippus, like his fellow Stoic Antipater, sees misogyny as something negative, a disease, an aversion to something good. This is the conflict or change of philosophically controversial views for ancient writers. Ricardo Salles suggests that the Stoicist view, in general, was that "[a] man can not only alternate between loving and hating women, between philanthropy and misanthropy, but can be incited towards one or the other".

Aristotle has also been accused of being a misogynist for having written that women are inferior to men. According to Cynthia Freeland (1994):

Aristotle says that the value of men is in command, that of the woman lies in obeying; that 'the matter yearns for form, as the woman for man and the ugly for the beautiful'; that the woman has less teeth than the man; that the woman is an incomplete man or 'so to speak, a deformity': that it contributes only as matter and not as a general form to the next generation; that inappropriately ]

In Routledge's Philosophical Guide to Plato and The Republic, Nickolas Pappas describes the "misogyny problem" and states:

In the Excuse me.Socrates calls those who pray for their life in court "not better than women" (35b) [...]. The Timaeus warns men that if they live immorally they will reincarnate as women (42b-c; cf. 75d-e). La Republic contains several comments of the same style (387e, 395d-e, 398e, 431b-c, 469d), evidence of contempt for women. Even the words of Socrates, in their bold proposal on marriage [...] suggest that the woman is made to "belong" to men. He never says that man can belong to women [...]. It is also necessary to take into account the insistence of Socrates that man overcomes women in any task that both sexes try (455c, 456a), and his observation in Book VIII that a sign of a moral flaw of democracy is the sexual equality that promotes (563b).

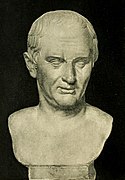

Another meaning of the term Misogynist is found in the Greek —misogunēs (μισογύνης)— in Deipnosophistae (above) and in Plutarch's Parallel Lives; it is also used as a title for Heracles in the Phocion story. It was the title of a work written by Menander, of which we know from book VII (on Alexandria) of the 17 volumes of Strabo's Geography, and Menander's quotes in Clement of Alexandria and Stobaeus which deal with marriage. Menander also wrote a work called Misoumenos (Μισούμενος) or The Man (She) Hated. Another Greek work with a similar name, Misogynists (Μισόγυνος) or Odia Mujeres is mentioned by Marcus Tullius Cicero (in Latin) and attributed to the poet Marcus Atilius Regulus.

Cicero establishes that the Greek philosophers considered that misogyny was suffered because of gynophobia, fear of women.

It is the same as with other diseases; like the desire for glory, a passion for women, that the Greeks called "Filoginia: and therefore all evils and diseases are created. But those feelings are the opposite of these, they must be feared by their foundation, such as hatred of women; this is represented in "Odia Mujeres" of Atilio. Or the hatred of the whole human species, like what is said to have been done by Timon, whom they call the Misanthrope; of the same kind of inhospitality. And how all these diseases come from a fear of the things they fear and avoid.Cicero TuculanasCentury I, DC.

The most common form of this word is misogunaios (μισογύναιος).

- There are also some people easily satisfied with their connection to the same woman, being at the same time mad by women and hate women. - Philo, Special laws, centuryI.

- Allied to Venus in honorable positions Saturn makes his subjects haters of women, lovers of the old, solitaires, not pleasant to meet, without ambitions, haters of the beautiful,... — Ptolemy, "Quality of the soul," Tetrabiblos, centuryII.

- I'll prove to you that this wonderful teacher, this hate women, it is not satisfied with ordinary pleasures during the night. — Alcifrón, "Thais to Euthydemus", centuryII.

The word is also found in the Anthology Vettius Valens' and the Principles of Damascene.

In summary, the Greek literature views misogyny as a disease—antisocial behavior—in the sense that it was contrary to their perceptions of the value of women as wives and of the family as the foundation of society. This is widely known in the secondary literature.

Religion

Ancient Greece

In Misogyny: The World's Oldest Prejudice, Jack Holland asserts that there is evidence of misogyny in the mythology of the ancient world. In Greek mythology according to Hesiod, the human race has experienced a peaceful, autonomous existence as a companion to the gods before the advent of women. When Prometheus decides to steal the secret of fire from the gods, an enraged Zeus decides to punish humanity with an "evil to his delight". This "evil" it was Pandora, the first woman, who carried a container (erroneously described as a box) that she was forbidden to open. Epimetheus (Prometheus's brother) overwhelmed by her beauty, ignores Prometheus' warnings about her, and marries Pandora. Pandora, by not resisting the curiosity to open the container, unleashes all the evils on the world; childbirth, sickness, old age, and death.

Buddhism

In his book The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender, Professor Bernard Faure of Columbia University argues that "Buddhism is, paradoxically, neither as sexist, nor as egalitarian as is usually thought." She adds: "Many feminist scholars have stressed the misogynist character of Buddhism." He stresses that Buddhism morally exalts its male monks, while the mothers and wives of the monks also play an important role:

While some scholars see Buddhism as part of an emancipation movement, others see it as a source of oppression. Perhaps this is only a distinction between optimists and pessimists, or between idealists and realistic [...]. As we begin to realize, the term "goodness" does not designate a monolithic entity, but encompasses a series of doctrines, ideologies and practices, some of which seem to invite, tolerate, and even cultivate the "other" in their margins.

Christianity

Differences in traditions and interpretations of scriptures have caused segmentation in different conceptions of Christianity that differ in their beliefs regarding the treatment of women.

In The Troublesome Helper Katharine M. Rogers says that Christianity is misogynistic and lists what she claims are examples of misogyny in the Pauline Epistles. She states:

The foundations of Christian misogyny—its guilt for sex, its insistence on female subjugation, its fear of female seduction—are all in the epistles of St.Paul.

In Studies in Feminist Literature: An Introduction, Ruthven references Rogers' book and argues that the "legacy of Christian misogyny was cemented by the 'Fathers' 39; of the Church, like Tertullian, who thought that a woman was not only "the entrance of the devil" but also 'a temple built over a sewer'".

However, other scholars have argued that Christianity does not include misogynistic principles, or at least that a correct interpretation of Christianity would not include misogynistic principles. David M. Scholer, Biblical scholar at Fuller Theological Seminary, states that the verse Galatians 3:28 ("There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free; there is neither male nor female; for ye are all one in Christ Jesus") is "the fundamental Paulian theological basis for the inclusion of women and men in conditions of equality and mutual respect in all the ministries of the Church". In his book Equity in Christ? Galatians 3:28 and the gender dispute, Richard Hove argues that —while Galatians 3:28 says that one's sex does not affect salvation— "there remains a pattern in which women must emulate submission of the Church to Christ and to the husband is to emulate the love of Christ for the Church".

In Christian Men Who Hate Women, clinical psychologist Margaret J. Rinck writes that Christian social culture often allows a misogynist to "misuse the biblical ideal of submission& #3. 4;. However, she argues that this is a distortion of the "healthy relationship of mutual submission"; which is actually specified in Christian doctrine, where "love is based on deep mutual respect as the guiding principle of all decisions, actions and plans". Likewise, Catholic scholar Christopher West argues that & #34;male dominance violates God's plan and is the result of sin".

Islamic

The fourth chapter of the Quran (or sura) is called "Women" (An-Nisa). Verse 34 is a key text in the feminist critique against Islam.The verse states: "Males have authority over women because Allah has made [a] some of them to excel others, as they pass outside of the property of him; good women are therefore obedient, keeping the hidden as Allah has kept, and [for] those on whose part you fear desertion, admonish them, and leave them alone in the sleeping places and beat them, and then if they obey you, they will not find a way against them; Allah is great, he is wonderful & # 34;.

In his book Case Study: Popular Islam and Bangladeshi Misogyny, Taj Hashmi discusses misogyny in relation to Muslim culture (particularly in Bangladesh), he writes:

Thanks to the subjective interpretations of the Quran (almost exclusively for males), the preponderance of the misogynist mullahs and the Sharia law retrograded in most "Musulmanes" countries, Islam is known as the promoter of misogyny in its worst form. Although there is no way to defend the so-called "large" traditions of Islam as libertarian and egalitarian with respect to women, we can draw a line between the texts of the Qur'an, the corpus of writing and the openly misogynistic words pronounced by the mullah that has very little or no relevance to the Qur'an.

In his book No god but God, University of Southern California professor Reza Aslan writes that "misogynistic interpretation" it has been persistently attached to An-Nisa, 4:34 because commentaries on the Qur'an 'have been the exclusive domain of Muslim males'.

Sikhism

Scholars William M. Reynolds and Julie A. Webber have written that Guru Nanak, founder of the Sikh faith, was a "fighter for women's rights"; he was not "by any means misogynistic"; in contrast to some of his contemporaries.

Scientology

In his book Scientology: A New Slant on Life, L. Ron Hubbard writes the following passage:

A society in which women are taught anything other than the management of a family, the care of men and the creation of the future generation is a society that is in the process of extinction.

In the same book he also writes:

Historians can link the point where a society begins its most pronounced decline at the moment when women begin to participate, on equal terms with men, in political and business matters, as this means that men are decadent and women are no longer women. This is not a sermon on the role or position of women; it is a statement of a simple and basic fact.

These passages, along with similar ones from Hubbard, have been criticized by Alan Scherstuhl of The Village Voice as hate speech against women. However, Baylor University professor J. Gordon Melton writes that Hubbard later discarded and repealed most of his views on women, Melton claims that Hubbard's points simply echo the common prejudices of the time. Melton has also stated that the Church of Scientology welcomes both genders equally at all levels—from leadership positions to audits, etc.—as Scientologists view people as spiritual beings.

Philosophers

Many Western philosophers have been accused of being misogynistic, including René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, David Hume, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, G. W. F. Hegel, Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, Otto Weininger, Oswald Spengler, and John Lucas.

Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer has been accused of being a misogynist for his essay "On Women" (Über die Weiber) in which he expresses his opposition to what he calls "Teutonic-Christian stupidity"; in women's affairs. He argues that women & # 34; by nature must obey & # 34; as they are "childish, frivolous and shortsighted". He claims that no woman has ever produced any great art or "any work of transcendent value". they possessed no real beauty:

He's just a man whose intellect is clouded by his sexual impulse that could give the name to the weak sex to those of smaller size, race of narrow shoulders, wide hips and short legs; all the beauty of sex is tied to this impulse. Instead of calling them beautiful, it would be fairer to describe women as antistatic sex.

Nietzsche

In Beyond Good and Evil, Friedrich Nietzsche notes that control over women was a condition of "every advanced culture". In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, there is a female character who says "Do you go to women? Don't forget the whip!". In The Twilight of Idols, Nietzsche writes "Women are considered profound. Because? Because we never considered its depths. But the women are not even superficial". There is controversy over these questions, and whether or not there is misogyny in them, whether their polemic against women is meant to be taken literally, and the exact nature of his opinions about women.

Hegel

Hegel's perspective on women has been said to be misogynistic. Some passages from Elements of the Philosophy of Right are frequently used to illustrate Hegel's alleged misogyny:

Women are capable of education, but they are not done for activities that require a universal faculty such as the most advanced sciences, philosophy and certain forms of artistic production... Women regulate their actions not by the demands of universality, but by arbitrary inclinations and opinions.

Feminist theory

Adherents of this current claim that part of the misogyny results from the Virgin-Prostitute complex, the inability to see women as more than "mothers" or "whores"; people with this conception place each woman in one of these categories. Another variant of the model is that one of the causes of misogyny is that some men tend to think in terms of a virgin/whore dichotomy which translates into men considering "whores" to any woman who does not adhere to a patriarchal standard of sexual purity, they even despise victims of abuse and/or gender violence, alluding that they are useless.

Feminist Marilyn Frye argues that misogyny is, at its root, phallogocentric and homoerotic. In The Politics of Reality, Frye says there is a misogynistic character in C. S. Lewis's fiction of 'Christian Apologetics'; she argues that such misogyny privileges the man as the subject of erotic attention. He compares Lewis's ideals in gender relations to male prostitution rings, arguing that they share the view of men who seek to dominate other people as less likely to assume submissive roles by a patriarchal society, but do so as a mockery. theatrical towards women.

At the end of the twentieth century, second wave feminist theorists argued that misogyny is both the cause and the result of a patriarchal social structure.

Sociologist Michael Flood argues that "misandry lacks the systemic, transhistorical, institutionalized, and legislated antipathy of misogyny".

Criticism of the concept

Camille Paglia, a self-proclaimed "maverick feminist "author who has often been at odds with other academic feminists, argues that there are serious flaws in the interpretation of Marxism-inspired misogyny, used frequent by the second wave of feminism. On the contrary, Paglia argues that a close reading of the historical texts reveals that men do not hate women, but fear them.

Contenido relacionado

Quarrel

Mulatto

Ideology