Minuet

Minuet or minuet is an ancient traditional dance of baroque music originating from the French region of Poitou, which reached its development between 1679 and 1750.

It was introduced under the name minuet at the French court by Jean-Baptiste Lully (1673), who included it in his operas and, from that moment on, it was part of operas and ballet. This elegant and majestic dance of figures supplanted the old courante during the Rococo period, which came to be called the “age of the minuet.”

Great composers of classical music have used it for their works (Don Juan, by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart), adapting it as an instrumental composition with a ternary and moderate rhythm. It usually has a humorous character and is part of sonatas and symphonies. It was one of the favorite dances of Louis XIV and his court.

At first, the ternary time minuet was quite fast, but over the course of the 17th century it moderated its movement. The minuet is made up of two sections with repetition of each of them. It is one of the optional dances of the suite: it is generally inserted after the zarabande and before the jig. In its classical form the minuet includes:

- Exhibition: (a) first topic with repetition; (b) second theme with repetition.

- Threesome with repetition, usually changing the instrumental set or tonality

- Re-exposition of the first two themes without repetition and with optional elbow.

It is the only dance from the suite preserved in the sonata. Starting with Ludwig van Beethoven it was progressively replaced by the scherzo.

Etymology

The term has been adapted, under the influence of the Italian minuetto, from the French menuet, diminutive of menú ('tiny'), which comes from the Latin minutus: 'tiny'. Minuet is a term that only appears in musical scores. Perhaps he was referring to the 'tiny steps' (pas menus) with which this dance is danced. In the period when it became more fashionable, it was a slow and ceremonious dance.

The dance

The origin of this French court dance is difficult to locate, but it is believed that it emerged in the court of King Louis XIV in the 1690s.

Composers such as Praetorius or Rameau considered that the minuet originated from the branle de Poitou, however the differences between both dances do not allow this theory to be considered solid, although it is not ruled out that it could be one of its possible beginnings.

The minuet quickly became the court dance par excellence, its graceful and apparently simple steps gave this dance enormous elegance, despite having complex patterns and requiring precise execution to perform the steps according to the music.

In France the minuet was performed in a slow tempo of 3/4, which allowed greater emphasis on the steps, highlighting the elegance of the movements. In other countries like Italy the dance was danced at a faster tempo.

The choreographic literature contains many writings related to this society dance, which became the queen of dances both in the palace and on the stage. The first mention of the minuet dates back to 1664, published by Guillaume Dumanoir in his treatise Le mariage de la musique avec la dance.

The minuet made its appearance shortly afterwards in Lully's operas and spread rapidly, but specific information on the movements and steps was not available until the early 1700s, when the Beauchamp-Feuillet notation system of the baroque dance and Raoul Feuillet published Chorégraphie, ou l'art de d'écrire la danse in 1701.

During the 18th century, they attempted, through their writings and teaching, to preserve its primitive purity and to preserve it from the contaminations, simplifications, and over-popularizations caused by widespread salon practice. The task of these teachers was, once again, to teach students, regular or occasional, the rules of the noble dance, as opposed to the contradance.

Among the most significant works of the 18th century is the manual Le maître à danser (Paris, 1725) by the French choreographer Pierre Rameau, which was, without a doubt, the most complete work dedicated to this dance.

The importance of Rameau's book should not lead to the conclusion that the minuet was presented in a single and unalterable form. Court dance teachers could (using their title) give the dance their own style and execution that was more suitable for this society dance.

On the other hand, while at court and in the city they managed to regulate this dance, in the provinces there was often evidence of great ingenuity and originality.

Since Rameau wrote that "the most appropriate thing one can do is the best. When you know how to dance the minuet perfectly, you can, from time to time, make some changes," the path was left open to both concision and improvisation.

After a period of relegation, the minuet came back into fashion in the 1880s. Despite the acceptance it had among society, and the imagination put into it by dance teachers, it did not survive for more than fifteen years, although it was practiced until the arrival of the First World War.

The steps of the minuet

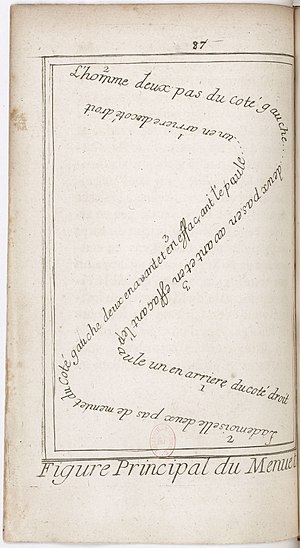

The dance began with the dancers showing respect to the figure who was presiding over the dance, for example a King or a nobleman, and later to each other. Once this was done, the dance took place in a rectangular area, in which the dancers performed different patterns in diagonally opposite positions, performing minuet steps and forming the pattern of an imaginary zeta on the floor, meeting in the middle, a moment in which the right hand is presented first, after another complete turn the left hand, ending with both hands and saluting again. Normally only one couple danced in each piece.

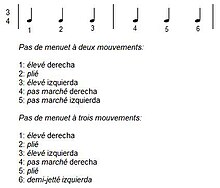

The minuet is played in 3/4 time and the basic step pattern consisted of taking four small steps to the quarter note rhythm for 2 measures starting with the right foot. The steps could be very varied, such as demi-coupés, demi-jettés, or pas marchés.

Two of the most common step combinations were the pas de menuet à deux mouvements and pas de menuet à trois mouvements.

However, depending on the time or the country, the patterns and steps underwent different variations, changing the steps, the accentuation of the beat, repeating patterns... In addition to dancing two or four couples and introducing elements typical of the typical dances of each zone.

Minuet in baroque instrumental music

The first examples of minuets apparently intended to accompany dancing are found in the Kassel Manuscript and in the Philidor Collection.

The study of these sources can shed light on the early development of music as a musical form, much of this printed music and manuscript collections of music to accompany dance, remains unedited, we can find numerous copies in France and England.

The earliest minuet work (or at least the first with greater importance) is found in Lully's theatrical works, these are 92 minuets which appear named in his ballets and operas between the years 1664 and 1687. Several of his proposals include minuet movements (for example, in his opera Armide) although apparently they were not intended to accompany dancing.

Like most dances of the 17th century, the minuet is included in the French piano and suite set French, generally (along with other still popular dances such as the bourrée and the gavotte) that appear after the zarabande, many composers include minuets in their compositions such as: Chambonnieres, Lebegue, Louis Marchand and the minuets including Anna Magdalena Bach's notebook. In addition, many minuets were included in manuscript collections of guitar and lute music (most still unedited), and movements (usually without the dance title) found in organ music collections.

The minuet is generally treated fairly simply, with its characteristic clarity of rhythm and phrase retaining even the occasional Double and appearing to be free of complex textures and ambiguous rhythms.

Although we must know that some composers experimented with irregular phrase structures, as is the case of the second minuet of the collection Pièces de harpsichord (Paris 1702) by Louis Marchand, it is structured in ten measures divided into five-bar phrases.

The minuet was a social dance from the 17th century England. As with other forms of baroque dances such as the Allemande, courante and gigue. The Italian-style minuet differs from mainstream European taste in a preference for faster tempos involving frequent use of 3/8 or 6/8. The melodic movement of the Italian minuet had a longer phrase than in French dance (usually eight measures instead of two or four)

Telemann and Bach write minuets of both types, Bach uses 3/4 time (regardless of tempo). His minuets are found in the keyboard scores and suites, in chamber music for solo and accompanied violin, cello and flute in three of the four orchestral suites, and in the First Brandenburg Concerto. This last minuet has been described as a Rondeau form (due to its ritornello form of three successive sections, a trio in the relative minor, the first more lively (Polacca) and a second, binary in the tonic.

Some of the dancers who have danced to the music of Bach's minuets insist that this music is suitable for the accompaniment of the dance, both for the structure of the phrase, as well as for the rhythmic play and elegance, Bach's proposal fits perfectly with the dance movements.

Classical and neoclassical minuets

Minuets were one of the most popular dances among the European aristocracy during the 18th century, being one of the greatest influences of this type of music. The complex and elegant content of this dance suited the Rococo environment of this period, and the relative simplicity of the phrases and harmonic movement made it a perfect medium for experimenting with long structures based on harmonic contrast and tonal regions, while which allowed the introduction of other ternary styles and more contrapuntal elements. By the middle of the 18th century, in fact, the minuet was the only major baroque dance that had survived as a best-known form, which was logically included in sonatas, string quartets and symphonies: the largest musical forms of more than one movement.

It was probably included in a symphony for the first time by Italian composers at the beginning of the 18th century, with movements indicated with the terms 'tempo di minuetto' that were included in the overtures of operas that were later published independently calling them 'symphonies'. For example we find the minuet tempo of the overture to Narcissus by D. Scarlatti, typical of his time and in the usual binary form of late Baroque dance forms, based on a rhythmic motif.. Quite a few of Sammartini's symphonies end with a similar minuet movement, as do the symphonies of C.F. Abel, Johann Stamitz, M.M. Monn and some of Haydn's early keyboard sonatas.

Finales in minuet form became quite frequent in the symphonies, concertos and sonatas of composers influenced by English music during the second half of the century XVIII. These movements, usually headed with a “tempo di minuetto” (or even the hybrid German-Italian term “menuetto”), often included the characteristics of the sonata form, while maintaining the features of measure., tempo and phrasing. For example, the third movement of Thomas Arne's Third Symphony, marked 'tempo di minuetto', begins with an exposition section presenting two contrasting themes and after repeating this section, a brief development It combines the motifs by transforming them with some quick modulations, followed by a modified restatement of the beginning. The Concertante Symphony by J.C. Bach in E flat includes a more complicated minuet finale: he combines this minuet-sonata form with a short trio in ternary form after which da capo is repeated. More examples of sonata form applied to minuet movements can also be found in the work of Mozart or Haydn.

Other formal schemes used for minuetto movements also drew on the Rondo form. It was common to see this in divertimentos and serenades, variations of binary minuets and, the best-known example, in minuets with contrasting trios in thematic material and character. This last form was the most common and was usually included as the third movement (of four) in the symphonies and string quartets of around 1770. The usual form was a ternary minuet followed by a shorter ternary trio repeating da Capo the minuet. As this form developed over time, the greater the contrast between the minuet and the trio, as occurs in Haydn's quartet op.77 number 2. It was also common to include dramatic elements such as irregular phrases, etc. in these movements.

On the other hand, functional minuets – for dances – became short, with some theorists such as Rouseeau and Honoré Compan defining how many measures they should have and how to divide the phrases and structure the music. The theory said that the minuet should be developed in 16 measures divided into phrases of two or four measures. On the other hand, the surviving descriptions of the dances indicate that a complete performance lasted 100 measures. Apparently, the musicians improvised ornamentations on the successive repetitions that were made, creating varied forms; or they also played different minuets successively.

As an aristocratic dance, the minuet maintained its place in opera and ballet and of course in ballrooms and concert halls, especially in France, where theatrical minuet choreography still survives. Minuets were included in Grétry's Céphalus and Procris; in Orfeo by Gluck (in its Parisian version); or also in Don Giovanni by Mozart.

The authors of the 19th century were not so interested in the minuet, although composers such as Brahms and Schubert included minuets in numbers of their works. Bizet also used this form in his music for L’ arlesienne and in the C symphony. Neoclassicism at the beginning of the 20th century brought new interest to the minuet, as can be seen in Masques et bergamasques by Fauré, in the bergamasque suite by Debussy or also in works by Jean Français, Bartók, Ravel or Schoenberg.

Contenido relacionado

Lacuna Coil

Carnota (A Coruña)

Claes Oldenburg