Milton Friedmann

Milton Friedman (New York, July 31, 1912 - San Francisco, November 16, 2006) was an American economist, statistician, and academic of Jewish origin, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics for 1976 and one of the main figures and referents of liberalism. A professor at the University of Chicago, he was one of the founders of the Chicago School of Economics, a neoclassical free-market school of economics. Along with John Maynard Keynes and Friedrich Hayek, Friedman is considered one of the most influential economists of the 20th century.

Ideologically liberal, Friedman spent much of his career criticizing mainstream Keynesianism in the mid-XX century, calling Keynesian theory as "naive". Friedman nonetheless incorporated Keynesian language into his work, although he was always critical of the conclusions of Keynesianism. His macroeconomic alternative focuses on monetary factors and is known as monetarism. Friedman proposed a smooth and gradual expansion of the money supply as the ideal monetary policy.He also developed the concept of the natural rate of unemployment, and predicted the stagflation crisis in the United States ten years before it occurred.

Friedman was an advisor to the governments of Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom. Also, his economic thought has been very influential in the policies of some post-Soviet states. His monetary theory inspired the actions taken by the United States Federal Reserve in response to the 2008 financial crisis.

Biography

Friedman was born in the New York borough of Brooklyn. He was the fourth and last child of a humble Jewish family consisting of Sarah Ethel and Jeno Saul Friedman, Jewish immigrants from central Europe, his father died when Friedman was fifteen years old. Despite this, and due to the great economic effort made by his family and by himself paying for his studies, Friedman studied Economics at Rutgers University. After that he returned to Chicago to collaborate as a researcher with Henry Schultz in demand measurements.

In 1935 he began working for the Economic Association of Natural Resources Committee and in 1937 left the position to join the National Bureau of Economic Research, where he studied the income structures of the liberal professions.

He was a student of Simon Kuznets and Arthur Burns. He worked as an economist for various federal agencies in the city of Washington from 1935 to 1940 and from 1941 to 1943. In 1946 he presented his thesis. A professor at the University of Chicago from 1946 to 1976, he also taught at the universities of Wisconsin, Princeton, Columbia, and Stanford.[citation needed] In 1977 he retired as a teacher.

Researcher at the National Bureau of Economic Research, 1937-1981. Active member of the Republican Party, he was special economic adviser to, among others, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and George W. Bush. He president of the American Economic Association in 1967. In 1947 he founded with Hayek and others the Mont Pèlerin Society, of which he was elected president in 1972.

From 1977 until his death, he was a Senior Research Fellow at the Hoover Institute at Stanford University.

He was also a member of the American Philosophical Society and the National Academy of Sciences.

In 1938, he married fellow economist Rose Director Friedman, whom he met when they were both studying at the University of Chicago in a class taught by Jacob Viner. Together they created the Milton and Rose D. Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice. They also co-signed several books.

In 1941, with the American entry into World War II, he was assigned to the Treasury Department, where he was in charge of fiscal policy during the war period. In 1943 he was appointed director of the Statistical Association at Columbia University, in which he dealt with problems related to military production. In 1953 he obtained a Fullbright scholarship, which enabled him to stay at the University of Cambridge, where there was then a wide debate around Keynesian ideas.

He advised a multitude of governments, many of which applied his liberal economic proposals, appearing in the media. He wrote in the magazine Newsweek (1966-1984).

Thought

One of Friedman's contributions to economics is his study of the consumption function. Unlike Keynes, who said that the consumption of a period depended exclusively on the income of the same period, Friedman postulated that this depended on permanent income, that is, on long-term income.

This new approach had an emphasis on consumer expectations and projections. Along with Edmund Phelps, he corrected the Philips curve. He introduced the role of expectations in this model.

Academic contributions

Milton Friedman was a monetarist. He proposed solving inflation problems by limiting the growth of the money supply to a constant and moderate rate.

An empirical economist, he was a specialist in statistics and econometrics. A defender of the free market, he was the best-known leader of the Chicago School due, in part, to the fact that his writings are so easy for the man in the street to read. He opposed Keynesianism at its peak, in the 1950s and 1960s.

In his explanation of the demand for money (1956) Friedman states that the demand for money is a function of the ratio between human and non-human wealth, the nominal interest rate, expected inflation, the real price level, the preference function of money over other goods and, naturally, of income. But unlike Keynes, Friedman, more focused on giving a long-term explanation, considers permanent income; that is to say, the value updated to the current date of the future capitals originated from a stock of wealth since it includes not only quantitative or material aspects.

Another contribution by Friedman is the revision of the Phillips curve, of Keynesian inspiration, which inversely relates levels of unemployment and inflation. Friedman considers that unemployment would be voluntary if it were not for the existence of a natural unemployment rate, the NAIRU (non accelerating inflation rate of unemployment), as a consequence of the limitations imposed by governments and other public institutions. An example of this is the prohibition of certain types of contracts.[citation needed] Friedman's vision conceives of the market as a rational system of resource allocation, capable of correcting its long-term imbalances.

In Capitalism and Freedom (1962) and Free to Choose (1980) he asserted that only an institution such as the market could guarantee the freedom of individuals and proposed leaving areas priorities such as education and health in the hands of free competition. Friedman's theory says that people's consumption is not affected by current income. If consumers receive an unforeseen income, it is fully saved for consumption later. This idea suggested that the State's fiscal stimuli did not have a significant effect. This theory, which was a central pillar of the monetarist model, would be refuted in the light of new studies, since consumer behavior is more short-term than what Friedman predicted, since people who receive some unexpected benefit tend to spend part of it immediately.. Various economists have shown that consumers are short-sighted when they stop receiving money, they reduce spending, contrary to Friedman's arguments.

Friedman posited market solutions to all sorts of problems—education, health care, the illegal drug trade—that almost everyone else thought required extensive state intervention. Some of his ideas were to replace pollution regulations with a system of pollution permits that companies can buy and sell. And some of his proposals, like eliminating licensure procedures for doctors and abolishing the Food and Drug Administration, are considered bizarre even by most conservatives.

When a government tries to reduce unemployment below that natural rate through very expansive monetary policies, in the short term it can succeed. But economic agents end up realizing that if there is inflation with equal wages, their ability to purchase goods and services is diminished. In such a way that they discount this effect, and in the next review of their contracts they will raise their salaries, which encourages a higher level of unemployment, any systematic attempt by governments to reduce unemployment ends up creating inflation without solving the problem. unemployment. There may even be a point from which the Phillips curve turns into a positive sloping curve, in such a way that unemployment and an increase in inflation are linked. That happened in the oil crises of the 1970s, a situation that Keynesian theory was unable to explain.

According to Friedman, the success of government intervention is very limited, and what they must do is eliminate the restrictions that prevent the natural unemployment rate from settling to a lower level. Friedman considered that, just as an expansive monetary policy can create economic crises, a restrictive policy can also be detrimental, through price deflation. He made this clear in 1963 when he published, together with Anna Schwartz, a voluminous volume entitled A Monetary History of the United States, 1897-1958 . Where he argues that the Great Depression was a consequence of the implementation of wrong policies by the Federal Reserve.

Friedman also argued that monetary policy has real effects on employment in the short run, but in the long run it has only nominal effects on prices. Later part of this theory would be refuted by various studies.

He was one of the main promoters of the policy known as monetarism. Decades later, the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England adopted his doctrine in the late 1970s, but would abandon it given its infeasibility a few years later. Friedman argued that steady growth in the money supply would keep the economy stable.

The United States and the United Kingdom tried to implement the monetarism preached by Friedman in the late 1970s, the results were disappointing: in both countries, the money supply failed to prevent serious recessions. The Federal Reserve officially adopted monetary targets outlined by Friedman in 1979, but abandoned them in 1982 and officially in 1984, when the unemployment rate exceeded 10%. Since then, the Federal Reserve would adopt policies contrary to Friedman's postulates. Secondly, the fact that since the beginning of the 1980s, inflation has remained low, recessions have been brief and mild, contributed to the discredit of his theory. And all this despite the sharp fluctuations in the money supply, which the monetarists criticized and which led them—even Friedman—to predict economic disasters that never materialized. David Warsh of The Boston Globe noted that "Friedman spearheaded his predicting inflation in the 1980s, during which he was profoundly and frequently wrong."

Proposals for public policies

He advocated liberal measures. One of them was the establishment of the educational bonus, with the idea of encouraging the educational demand according to the preferences of the parents. He proposed making prices more flexible, deregulation and privatization, individualized pension systems, the legalization of drug use and even prostitution.

He defended the abolition of compulsory military service,[citation needed] of minimum wages and social security. He argued that the Hong Kong economy was the best example of a laissez faire capitalism economy.

In a general context of conservative revolution, Milton Friedman participated in the Republican Party. He advised Ronald Reagan in his presidential campaign and during his two terms, Reagan's economic policy was based on Friedman's ideas, which were based on a reduction in the weight of the state, low marginal tax rates on the highest incomes, the deregulation of the economy and monetary policy as the only tool to reduce inflation.

For Friedman, economic freedom tends to be generated by capitalism, and for this very reason socialism tries to make it impossible and statism to weaken.

In 1980, the US public television network PBS broadcast a ten-part series, written by Friedman, called Free to choose.

In 1991, Friedman affirmed that Colombia should not continue paying the price for the ineptitude of US laws on the issue of drugs. He considered that the legalization of drugs would transform the situation in Colombia, since he considered that because vice is illegal and not being able to execute the law, an environment of crime, wars, and gangs is created. He also affirmed that not only should the drug be legalized, but that it would be necessary to introduce it into the industrial field, so that medicines that help alleviate diseases such as glaucoma are produced with it. He also believes that hallucinogenic substances should be processed in pharmacies in order to guarantee their quality.

In 2003, he stated that “The environment is a vastly overrated problem. [...] We pollute by the mere fact of breathing. We are not going to close factories on the pretext of eliminating all carbon dioxide emissions from the atmosphere. It would be like hanging yourself right now!"

Influence in Chile

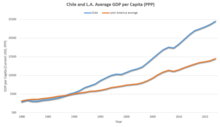

Friedman influenced the economic aides of the military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet even before the coup. Two years after this, in 1975, he visited Chile as a special guest of the Valparaíso Business School, by its Chilean alumni from the Chicago School (Chicago Boys). The economic program put into practice in Chile during the dictatorial regime of Pinochet by a group of Chilean economists, had a strong imprint of Friedman, most of them trained at the University of Chicago by Milton Friedman and Arnoldo Harberger.

The generals who had perpetrated the coup lacked the technical skills to intervene in the economy and the Chicago Boys took on this task of shocking treatment of the unstable Chilean economy. The US Senate Special Committee on Intelligence would later reveal that the economic measures implemented by the Military Government Junta in Chile immediately after the coup d'état were designed with the help of "CIA collaborators". According to the newspaper The Wall Street Journal (November 2, 1973), the Chicago Boys were eager for the hit and "impatient to launch" on the Chilean economy. The theoretical model that they had learned in Chicago from their professor Friedman was implemented without possible political opposition a year later. Friedman visited Chile for this reason and, together with Harberger, gave several talks and press statements about his recommended "shock treatment" for the Chilean economy, in his opinion, seriously ill.

The initial effects on the Chilean economy were severe. GDP fell by 12%, the unemployment rate rose to 16.5%, and the value of exports fell by 40%. But the system began to take hold in 1977, beginning what has been called the "boom", with positive figures in many areas, but with a constant high unemployment rate., from 17-15%, due, among other things, to the massive layoffs of public employees, officials of privatized companies and the loss of employment in the manufacturing and export sectors due to exchange rate policies and the opening of the economy. The "boom" would last until the economic crisis of 1982, strongly influenced by the world recession of 1980 and which was part of the Latin American debt crisis that caused a rise in interest rates. interest and difficulties in accessing new credit, weakening of real activity and a drop in terms of trade (copper had a sharp drop in price at the beginning of 1980). Chile was left unprotected in this international crisis due to its excessive dependence of the external market, the excessive indebtedness to private (domestic credit rose from 25%, in 1976, to 64% of GDP in 1982) and the fixing of the dollar (switch to exchange rate) which caused one of the deepest crises that affected the nation as a whole in the 1930s and the early 1970s. This caused a drop in GDP of 13.6% (the highest drop recorded by Chile since the 1929 crisis), a notable increase in unemployment with rates around 20% for several years, and the bankruptcy and intervention of numerous banks and financial institutions (60% of the credit market was intervened).

Friedman advocated the reduction of public spending (20%) and the number of public jobs (30%), the elimination of social policies and an initial increase in consumption taxes constituted the initial package of measures of Minister Sergio de Castro.

His collaboration with Pinochet's military dictatorship would be reproached, in an interview in 2000 Friedman attributed it "to the communists who tried to discredit anyone who had the slightest connection with President Pinochet." Later, Friedman referred to this issue by making an analogy between the Chilean military dictatorship and the Chinese dictatorship, where he gave lectures to economics students and met with the secretary of the Communist Party of China Zhao Ziyang, saying: «I gave lectures in both China and China. in Chile exactly the same conferences. I have seen many protests against me for what I said in Chile, but no one has objected to what I said in China. How do you explain it? » Despite this, a letter that was written by Friedman on April 15, 1975, addressed to the dictator Augusto Pinochet, would be published, in which Friedman expressed strong support for the Pinochet dictatorship and his regime. After having visited Chile on March 21, 1975, he wrote Pinochet a letter in which he thanked the dictator for his hospitality: "They made us feel as if we were really at home."

Nobel Prize in Economics

On October 14, 1976, it was announced that Friedman would receive the Nobel Prize in Economics "for his achievements in the fields of consumption analysis, history, and monetary theory and for his demonstration of the complexity of the politics of stabilization". The American newspaper The New York Times published a letter from two Nobel Prize winners, George Wald (Medicine) and Linus Pauling (Chemistry and Peace), in which criticized the awards committee for "a deplorable display of callousness" in awarding Friedman the award. Nobel laureate Salvador Edward Luria would also join, who described the committee's decision as "disturbing" and "an insult to the people of Chile who were burdened with the reactionary economic measures endorsed by Friedman" (Friedman and Friedman 1998, 596-7). In December, when Friedman traveled to receive the award, there were multiple and massive demonstrations. On December 14, 1976, four days later, the Nobel Prize winner Gunnar Myrdal published a long column in the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter, which would soon appear reproduced in the popular American magazine Challenge, where he criticized the Swedish Academy of Sciences for its secret practices in the election of said Nobel and argued that the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Economics should be discontinued since it was a political act.

Criticism and defenders

One of the first to criticize Friedman's theory and his postulates was Orlando Letelier, who in a column in The Nation criticized Friedman and the Chicago Boys for advising Pinochet to impose his program On the other hand, it emphasized the image of Friedman as the "intellectual architect and unofficial adviser" of the Chilean military regime. Letelier linked the "neoliberal" that at that time the Chicago Boys carried out, with the sustained and systematic violation of human rights in Chile.

Days later, the critic of Friedman and of the Pinochet regime in Chile was allegedly assassinated by agents of the Pinochet regime in the city of Washington. On September 21, 1976, in the heart of downtown Washington, an explosive attack blew up Letelier's car, killing her and her secretary Ronni Moffitt.

The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism is a book and documentary written by Canadian journalist Naomi Klein in 2007, critically discussing the influence of Friedman and his theory of the free market in different countries, how it was put to the test in countries that were far from free, how the unpopularity of the measures he recommended made it necessary to create chaos in order to implement them and how these measures failed, establishing a parallel with the failure of CIA-funded electroshock experiments in the 1950s.

Friedman's doctrine has been further criticized for the results of applying his theory, including that: in the first half of 1975, as part of the process of deregulating the economy, the price of milk in Chile was exempted from control, contrary to Friedman's theories that postulated that the free market would increase competition and lower prices, in practice the consumer price rose 40% and the price paid to the producer fell 22%. An economic failure was also attributed to his theories. By the end of 1975, the annual inflation rate in Chile had reached 341%, the highest inflation in the world, as a result of the application of monetarist theory. Consumer prices increased that same year by an average of 375%; wholesale prices grew by 440%. The Real Gross National Product contracted during 1975 by almost 15% to its lowest level since 1969, while, according to the International Monetary Fund, real national income "fell by 26%, leaving real income per capita lower than its level of the previous ten years. The 1975 decline in Gross Domestic Product reflects an 8.1% decline in the mining sector, a 27% decline in manufacturing, and a 35% decline in construction. Oil extraction fell by an estimated 11%, while transport, storage and communications fell 15.3%, and trade decreased by 21.5.

Liberal economic activist Johan Norberg, author of several books and documentaries in favor of economic globalization, considering his reading of Friedman's words as well as his reinterpretation of what Friedman interpreted as "crisis" 3. 4; (consequence of statist policies) and as a "shock" (the immediate application of a package of deregulation measures).

He also accused Klein and the anti-globalists of imposing a premise of unpopularity of free market economies, appealing to a fallacious generalization in order to associate economic-individual freedom with political-collective autocracy. For the author, just as for Friedman, the political freedom necessary to exercise a political democracy requires economic freedom (whether socializing or liberalizing policies of business activity are chosen); Among liberal economists, Friedman has been criticized for Joshep Salerno in his book Money: Sound and Unsound, published in 2010 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Last days

In 1976, he moved to San Francisco to join the Hoover Institution, where he continued to advocate for economic freedom. In 1998 he wrote a book together with his wife, entitled Two lucky people , where he recounts his memories. At the age of 91, in a journalistic note for the Financial Times, Friedman would renounce his own theory of monetarism, and say: "Control over the money supply as an objective in itself has not been exit. Today I no longer believe in it, as I once did".

He died of a heart attack on November 16, 2006, at the age of 94, in a hospital near the city of San Francisco, where he had lived since the late 1970s. He was survived by his wife Rose and her two children: Janet and David had four grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. Upon her death, her family requested that, in lieu of receiving flowers or gifts, all contributions desired be directed to the Milton and Rose D. Friedman Foundation.[citation needed] He was cremated and his ashes were scattered in San Francisco Bay.

Decorations and honors

- In 1952 he received the John Bates Clark Medal.

- In 1988 he received President Ronald Reagan's Medal of Freedom of the United States.

- In 1978 he received an Honoris Causa doctorate at the Francisco Marroquín University of Guatemala, in addition to an auditorium that was appointed in his honor in the same house of studies.

- Nobel Prize in Economics in 1976.

- He received honorary degrees from different U.S. universities. Japan, Israel and Guatemala, as well as the Grand Cordon of the First Class Order of the Sacred Treasure, granted by the French government in 1986.

Posts

- Essays in Positive Economics, 1953

- A Theory of the Consumption Function1957

- A Program for Monetary Stability1959

- Capitalism and Freedom1962

- Inflation: Causes and consequences1963

- The Optimum Quantity of Money and Other Essays1969

- The Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory1970

- Free to Choose: A personal statementwith Rose Friedman, 1980

- Friedman, Milton (1962). A program of monetary stability and banking reform. Editions Deusto (Barcelona). ISBN 978-84-234-0170-3.

- Friedman, Milton (1966). Capitalism and freedom. Rialp Editions. ISBN 978-84-321-1245-4.

- Friedman, Milton (1967). Tests on positive economy. Editorial Gredos. ISBN 978-84-249-2610-6.

- Friedman, Milton; Schwartz, Anna Jacobson (1971). A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960 (in English). Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00354-2.

- Friedman, Milton; Musgrave, R. A. (1972). Current political problems. Dopesa. ISBN 978-84-7235-024-3.

- Friedman, Milton (1982). Friedman against Galbraith. Editorial Union. ISBN 978-84-7209-144-3.

- Friedman, Milton (1982). Paro and inflation. Editorial Union. ISBN 978-84-7209-069-9.

- Friedman, Milton; Friedman, Rose (1984). The tyranny of the status quo. Editorial Ariel. ISBN 978-84-344-1023-7.

- Friedman, Milton (1985). A theory of consumption function. Editorial Alliance. ISBN 978-84-206-2036-7.

- Friedman, Milton; Friedman, Rose (1992). Freedom to choose: towards a new economic liberalism. Grijalbo. ISBN 978-84-253-1940-2.

- Friedman, Milton (1992). Paradoxes of money: towards a new economic liberalism. Grijalbo. ISBN 978-84-253-2472-7.

- Friedman, Milton (1994). Price theory. Altaya Editions. ISBN 978-84-487-0136-9.

- Friedman, Milton (1999). The monetarist economy. Altaya Editions. ISBN 978-84-487-1273-0.

- Friedman, Rose; Friedman, Milton (2004). Freedom to choose. Collectable RBA. ISBN 978-84-473-3194-9.

Contenido relacionado

World Bank

Ernest Hemingway

Americo vespucio