Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin (Михаил Александрович Бакунин in Russian) (Priamukhino, Torzhok, Russian Empire, May 30, 1814 - Bern, Switzerland, July 1, 1876) was a Russian political theorist, philosopher, sociologist, and revolutionary anarchist. He is one of the best known thinkers of the first generation of anarchist philosophers along with Piotr Kropotkin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Carlo Cafiero and Errico Malatesta. He is considered one of the fathers of this thought, within which he proposed the approaches of anarcho-collectivism. His legacy marked a strong influence for revolutionary socialism, militant atheism, the labor movement, anarcho-syndicalism and ethical-philosophical and critical positions of authoritarianism and political power.

Biography

He was born on May 30, 1814 in the village of Priamukhino, Torzhok district, Tver province. His father was of liberal ideology and had been a diplomat in Paris during the storming of the Bastille (7/14/1789). When Nicholas I ascended the throne, he retired to live in the countryside, where he owned land and a thousand serfs. Mikhail he was the eldest of five brothers and five sisters. His family was religious, but not excessively. in Russia by the tsar.

At the age of 15, he entered the St. Petersburg Artillery Academy. There he began to write, have fun drinking with his friends and getting into debt. He will spend three years there, but will be expelled for unruly behavior. He was transferred as a junior officer (práporshchik) of the Russian Imperial Guard to Minsk and Goradnia. From Minsk he wrote to his family:

I'm completely alone. An eternal silence, an eternal sadness, an infinite nostalgia are the companions of my loneliness. I have discovered, by experience, that the perfect solitude, so preached by the philosophy of Geneva, is the most idiot of sophisms. Man is made for society. A circle of relationships and friends who understand and divide with him their joys and their pains is indispensable. Voluntary loneliness is identical to selfishness and can a selfish be happy?

At that time, the repression of the Poles took place, which helped Bakunin to take a position against despotism. In 1834, he left the army and moved to Moscow, then already steeped in European romanticism. He studied philosophy for six years. He regularly read the French encyclopedists and also developed an admiration for Fichte and Hegel.He befriended Aleksandr Herzen and Nikolai Ogarev, supporters of the ideas of the socialist Saint-Simon, and who shared his admiration for Hegel. It is in this same period when, in Berlin, Karl Marx develops the same sympathies towards Hegel. It is also at this stage that he develops an epistolary love relationship and jealousy towards his sister Taniusha.

With the aim of obtaining a chair of philosophy or history at the University of Moscow, he organized a trip to study German philosophers. In 1840 he sailed for Berlin, where he met his sister Barbara and lived with Ivan Turgenev. There he will write:

Germany of 1840 is in full transformation; industry is born and, with this, the industrial proletariat, which is not yet a threat. It is the enriched bourgeoisie that demands its rights to feudal power. Germany, which so far has only been a lot of small states, wants to be a nation and demands unity and freedom.

In 1842, he settled in Dresden, the capital of Saxony, where he met Ruge, director of the Deutsche Jahrbücher magazine, where he wrote a revolutionary article under the pseudonym Jules Elysard. This article was quite successful in Russia. In 1843, he moved to Switzerland, where many German political dissidents were taking refuge. There he wrote a letter to Ruge, which was published in Paris in 1849, in the magazine Deutsche-französiche Jahrbücher. In Switzerland he met Weitling, the first German communist, and came into contact with the Vogt family. The Swiss police invited him to leave the country and the Russian embassy forced him to return to Russia, so he escaped to Belgium in 1844 and, from there, moved to Paris. In Paris he met Proudhon, George Sand, Marx, Engels and some Polish exiles. About Marx he wrote:

We were quite friends. [...]; then I did not know anything about political economy and had not yet liberated me from metaphysical abstractions and my socialism was just instinctive. He, though he was younger, was already atheist, a materialistic sage and a conscious socialist [...] We often saw each other, because I respected him much for his wisdom and for his passionate and serious devotion, though mixed with personal vanities, to the cause of the proletariat, and eagerly sought his conversation, always instructive and spiritual when he was not inspired by a petty hatred, which, unfortunately, happened very often. Yet there was no true intimacy among us. Our tempers didn't stand. He called me a sentimental idealist, and was right; and I was vain and wicked, and he was right.

De Engels wrote:

By 1845, Marx stood at the head of the German Communists, and shortly thereafter, with Engels, his constant friend, as intelligent as he, although less learned, but instead more practical and gifted, not less than he, for political slander, lies and intrigue, founded a secret society of German or authoritarian socialists.

In 1848, after returning to the French capital, he issued a fiery proclamation against the Russian Empire, after which he was expelled from France. The revolutionary movement of 1848 provided him with the opportunity to participate in a violent campaign of democratic agitation and for his participation in the Dresden Uprising of 1849 he was arrested and sentenced to death, a sentence later commuted to life imprisonment. Ultimately, Bakunin was handed over to the Russian authorities, who imprisoned him in the Peter and Paul Fortress in 1851, where he remained until 1857, when he was banished to a labor camp in Siberia. Taking advantage of a permit, he escaped to Japan, arriving at the port of Hakodate in 1861. From Yokohama, he traveled to San Francisco, crossed Panama, arrived in New York - where he was received by some famous people, such as the writer Henry Longfellow and met with people close to the local labor movements - and moved to England in 1861. The rest of his life was spent in exile in Western Europe, mainly in Switzerland.

Rivalry with Karl Marx

Bakunin established a more constructive friendship with Proudhon than with Marx, whom he accused of being authoritarian. About this relationship he wrote:

Marx, as a thinker, is on the right track. It has established as a principle that all philosophical, political, religious and legal revolutions are not the causes, but the effects of economic revolutions. It is a great and fruitful thought that has not been invented by him, much less, because he was already interviewed and expressed, in part, by many others. However, we owe it the honour to have solidly established it and put it as a basis for its entire economic system. On the other hand, Proudhon, when he did not do doctrine and metaphysics, possessed the true instinct of the revolutionary. [...] Marx is most likely to "theoretically" rise to a more rational system of freedom, but he lacks Proudhon's instinct.

Bakunin and Marx maintained constant friction within the First International Labor Association (AIT), founded in 1864, to which both belonged. In 1868, Bakunin was accused by Marx of being a Russian agent and asked to apologize publicly. In 1869, he was accused by the Marxist revolutionary Wilhelm Liebknecht of the same charges. Marx will accuse him again of being a Pan-Slav agent and of charging 25,000 francs a year for it. Bakunin, in addition, advocated anarchist positions within the AIT, which led him to be accused of conspiracy by Marx, whose followers brandished alleged letters written by Bakunin to Sergei Nechayev where he boasted of the conspiracies he perpetrated.

After disputes with Marxist members, Bakunin came into contact with Nechayev, who asked him to focus on making the revolution in Russia and convinced him with his nihilistic and terrorist ideas. A year later, in 1870, Bakunin decided to break his friendship with Nechayev, regretting this experience.

International Alliance of Socialist Democracy

At the beginning of the 1860s Bakunin founded a secret society in Italy, the International Fraternity. In 1864, the organization already had Italian, French, Scandinavian and Slavic members. In the texts of the organization it is said:

This organization aims at the victory of the principle of revolution on earth, with the radical dissolution of all existing organizations today, religious, political, economic or social, and the formation of a first European and then universal society, based on freedom, reason, justice and work.

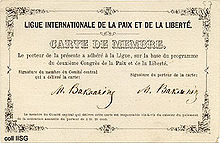

In 1867, a group of bourgeois democrats from various nations founded the League of Peace and Liberty and convened a congress in Geneva. Bakunin participated in said congress and was elected a member of the central committee. One of the founders of that league was Charles Lemonnier, a Saint-Simonian.

In 1868, the second congress of the League was held in Berne, Bakunin and other members of the International Fraternity tried to get the League to vote for socialist resolutions, but as the revolutionary socialists were a minority they decided to separate and found the International Alliance of Democracy Socialist.

The International Alliance of Socialist Democracy was founded in 1868 and its program called for a series of reforms that constituted the bases of its political doctrine:

- The abolition of national States and the formation in their place of federations constituted by free agricultural and industrial associations.

- The abolition of social classes and inheritance.

- Gender equality.

- The organization of workers outside the political parties.

However, the Alianza's entry into the Workers' International was rejected for being an international organization, since only national organizations were admitted. For that reason, the Alliance broke up and its members joined the International separately.

Propagation of anarchism

In 1869, he commissioned the Italian anarchist Giuseppe Fanelli to spread anarchism in Spain. Fanelli visited Madrid and Barcelona and met Anselmo Lorenzo, who would eventually found the CNT union in 1910 and who would share little correspondence with Bakunin.

In 1870 he founded the Committee for the Salvation of France, an association that led the insurrection of the Commune of Lyon.

In 1871 Marx convened a secret conference in London composed almost exclusively of his supporters, at which decisions were made that many considered removed the autonomy of the AIT sections. The Federations of the Jura (a mountainous area between France, Switzerland and Germany), as well as the majority of the sections of all the countries, rejected these agreements. In this context Bakunin joined the dissidents. Several leaders of the AIT who were dissatisfied with the decisions adopted by the Marxists were attacked from the London Council, and they were accused of being puppets of Bakunin, who was then in Locarno, Switzerland.

In 1872 the Congress of The Hague was held, attended by 21 worker delegates representing different sections and 40 men individually chosen and sympathizers of Marx. In the last vote, when a third of the representatives had already left, the expulsion of Bakunin was voted, as a court behind closed doors. Bakunin is accused of having founded secret societies, of having collected three hundred rubles as an advance for the translation of Capital, and of having intercepted a supposed letter from Bakunin to Nechayev, with whom he had been dating for two years. broken. In this letter, allusion was made to the creation by Mikhail Bakunin of a secret society that would conspire to take "dictatorial" control of the AIT. In the same congress the proposals of the London conference were ratified and it was decided to transfer the Congress to New York.

The day after the end of the Hague Congress, another is held in Saint-Imier, in the Swiss Jura, with delegates from Italy, Spain, the Jura and representatives from France and America, who unanimously agree to reject all decisions of the The Hague congress. This agreement is joined by the majority of the French sections, the Belgian federation, the American federation and, in England, the friends of Marx, Eccarius and Jung, who separated from him. The New York Council expelled the Jura Federation, but the Dutch section, which had remained neutral, joined the other seven federations in refusing to recognize the expulsion of that federation.

Death

In 1873, Marx and his sympathizers published a pamphlet entitled The Alliance of Socialist Democracy and the International Workers' Association, where they furiously criticized the Alliance. Bakunin, prematurely old, tired, and ill, applied to leave the Federation.

Bakunin spent his last years in Switzerland, living in poverty and with no encouragement other than his correspondence with small anarchist groups. Due to health problems, he was admitted to the hospital in Bern, where he died on July 1, 1876.

His grave is in the Bremgarten-Friedhof Cemetery in Bern, Switzerland, blackened by fumes from the nearby Geneva-Zurich motorway. On his grave it is written: «Remember the one who sacrifices everything for the freedom of his country ». This text and plaque were changed by the Cabaret Voltaire Dadaists in 2016, who adopted it as Dadaist. In its place is Bakunin's phrase in German: "Wer nicht das Unmögliche wagt, wird das Mögliche niemals erreichen; Whoever does not dare the impossible will never achieve the possible”, along with a bronze drawing by the Swiss artist Daniel Garbade.[2]

Thought

The anarchism he developed has been called anarcho-collectivism or collectivist anarchism. Along with Proudhon and later Kropotkin, he is one of the most important theoreticians of socialist anarchism, and is practically the first great promoter of anarchism as a political and popular movement.

Antistatism

Bakunin proposes an anti-statist organization, that is, the abolition of the State, without rejecting the term itself. Bakunin opted for the creation of the United States of Europe as a way of approaching the liberal idea of the American Revolution of 1776, when it became independent from the United Kingdom. For Bakunin, the failure of the liberal revolution in the United States is that the freedom that the constitution proclaimed was only for a minority that oppressed the rest. The challenge for Bakunin was to achieve a democracy like the American one in Europe but that would extend democracy to all and also free man from the monetary system, political power, economic power and religion.

Unlike Marxism, which believed that politics should create social conditions that would allow the individual to live above economic oppression, Bakunin believed that the socialist revolution had to start from the bottom up. He established a political order of individuals that formed communes, that in turn these communes would federate among themselves to collaborate and that these federations would federate among themselves in confederations. In this process, unlike Marxism, Bakunin does not separate peasants from urban workers and considers that this revolution corresponds to both at the same time.

Work

Bakunin gave great importance to work and to the fact that it developed under his idea of freedom:

As the ancient world, our modern civilization, which comprises a comparatively very restricted minority of privileged citizens, is based on the forced labour (by hunger) of the vast majority of populations.Bakunin. Federalism, socialism and anteologism. 1867.

For Bakunin, anarchism supposes a social liberation, without the need for a government or official authorities whose center of gravity is located in work, the production factor, its means and distribution. Society should be organized through the federation of producers and consumers (at the grassroots level) coordinated with each other through confederations. There would be no need, therefore, for governments, legislative systems or executive powers that monopolized violence.

Kropotkin's libertarian communism objected that Bakunin's vision maintained the concept of bureaucracy as a body in charge of monitoring and regulating work and its remuneration, ultimately a governmental nucleus. Bakuninist collectivism claims to value the work of the masses and considers their remuneration unfair under capitalism:

In the absence of all other good, this bourgeois education, with the help of the solidarity that unites all members of the bourgeois world, assures those who have received it, a huge privilege in the remuneration of their work - the work of the most mediocre bourgeois is paid almost always three or four times more than that of the most intelligent worker.Bakunin. Federalism, socialism and anteologism. 1867.

In an extensive letter signed in Marseilles in 1870, he deals with the issue of the fair distribution of wealth produced by national labor. For Bakunin, as national wealth increases, it tends to concentrate in the hands of fewer and fewer people, while the bourgeois argue that improving the conditions of the proletariat first requires bourgeois prosperity. According to Bakunin, the bourgeois system also produced commercial crises due to overproduction that left thousands of people jobless, and the suppression of small industrial, commercial and financial companies. In the same letter he makes a description of the consequences of capitalism. According to Bakunin, due to the fact that in capitalism it is necessary to sell the merchandise at the lowest possible price, it makes wages very low to reduce production costs. Then, the work of people also becomes a commodity, governed by supply and demand (for example, a prosperous industry, with highly demanded products, increases its production and therefore requires many workers, attracting them with an increase in wages, however, as soon as the labor supply exceeds the demand, the salary begins to fall), Bakunin considering the law of demand as something undesirable.

It is also interesting, he describes, that in the most politically democratic countries, such as England, the United States, Switzerland or Belgium, the workers, even with political rights, are slaves to their employers and therefore do not have the time or the independence necessary to exercise their citizenship rights. Those countries, says Bakunin, have a "kingdom day" or "of saturnales", which is the one of the elections, where their "masters" They are going to talk to them about equality and fraternity and to tell them that they are the sovereign people, but after that day everything remains the same. Bakunin says that this does not mean that he, as a revolutionary socialist, is not in favor of universal suffrage, but that he is in favor of exercising it to build a society without economic and social inequality.

For Bakunin, the socialists who participate in the bourgeois elections, as in the case of the socialists in Germany, are either wrong people or they are liars, since the only thing that is achieved with that is to separate the workers from the social revolution that is the only one that, according to him, would bring real freedom, justice and social welfare. This is because the State is nothing more than an oppressive yoke, and the institutions and political authorities serve to guarantee the privileges of the oppressing classes, and socialism can only be obtained if, at the same time, the State is destroyed. The alternative would be, it says verbatim, "the way of a free federation, of the freedom and work of all, towns, provinces, communes, associations and individuals, on the sole basis of equality and human fraternity."

Atheism

Bakunin was extremely critical of religion and advocated atheism. From his work one can deduce a very intense atheism and even a declared admiration for the figure of Lucifer, whom he considers a revolutionary in heaven against the autocratic power of God.

For Bakunin, the Catholic was the egotistical person par excellence, since he did Good out of love for himself, to have access to Heaven, and not out of love for others. Bakunin placed the Catholic priest on a par with witches, and did not distinguish between Christianity and any form of magic or primitive religion.

Bakunin goes back to the Old Testament to direct a furious criticism of Moses. Moses, in the Old Testament, receives the laws directly from God and imposes them on the people of Israel. That is to say, the State, the legislator, in the first place seeks its legitimacy in God in order to be a dictator.

He also considers religion pernicious for men because it makes them accept more easily that there are bosses in the world, coining the phrase: "One boss in heaven is the best excuse for there being a thousand on Earth."

Although Bakuninist atheism is very popular in anarchism, this extreme contempt for religion does not extend to all anarchism. Kropotkin, despite knowing Bakunin's work, does not give any importance in his texts to religion. For Proudhon, the origin of the State is not at all religious, but arises from the distribution of land property. In history, moreover, Christian anarchists like Leo Tolstoy abound.

Revolutionary organization and invisible dictatorship

Much of Bakunin's disagreements with Marx within the AIT were over criticism of Marx for trying to make the AIT an instrument for Marx's ideological cause rather than representing the workers. Bakunin claimed to be contrary to the doctrines and denied calling himself a philosopher. However, there were accusations on the part of Marx that Bakunin was conspiring to make the AIT an instrument of his own ideological cause. What there is certainty about, thanks to the known correspondence, is Bakunin's ideas on the leadership of revolutionary social movements that for Bakunin should be carried out through non-formalized, invisible supreme commanders, without recognizable parties or acronyms, an idea of political organization called invisible dictatorship, an idea derived from secret societies.

According to McLaughlin, Bakunin has been accused of being a closet authoritarian. In his letter to Albert Richard, he wrote:

There is only one power and one dictatorship whose organization is healthy and viable: it is that collective and invisible dictatorship of those who are allied in the name of our principle.

According to Madison:

[Bakunin] rejected political action as a means to abolish the state and developed the doctrine of revolutionary conspiracy under autocratic leadership, without taking into account the conflict of this principle with its philosophy of anarchism.

According to Peter Marshall: "It is hard not to conclude that Bakunin's invisible dictatorship would be even more tyrannical than a Blanquist or Marxist one, since its policies cannot be known or discussed openly."

Madison argued that it was Bakunin's plotting for control of the First International that sparked his rivalry with Karl Marx and his expulsion from it in 1872: "His approval of violence as a weapon against agents of the oppression led to nihilism in Russia and acts of terrorism elsewhere, with the result that anarchism became generally synonymous with murder and mayhem'. "invisible dictatorship" is not a dictatorship in any conventional sense of the word. His influence would be ideological and freely accepted, saying:

This dictatorship will be both healthier and more effective if it is not seen with any official power or extrinsic character.

Bakunin was also criticized by Marx and the International delegates specifically because his organizational methods were similar to those of Sergei Nechayev, with whom Bakunin was closely associated. amoral politics, he maintained a streak of cruelty, as a letter dated June 2, 1870, indicates: "Lies, cunning [and] entanglement [are] a wonderful and necessary means of demoralizing and destroying the enemy, though certainly not it is a useful means of obtaining and attracting new friends".

However, Bakunin began to warn his friends about Nechayev's behavior and severed all relations with Nechayev. Others further point out that Bakunin never attempted to gain personal control of the International, that its secret organizations were not subject to his autocratic power, and that he condemned terrorism as counterrevolutionary. Robert M. Cutler goes further, pointing out that it is impossible fully understand Bakunin's involvement in the League of Peace and Freedom or the International Alliance of Socialist Democracy, or his idea of a secret revolutionary organization that is immanent in the people, without seeing that they stem from his interpretation of the Hegel's dialectic of the 1840s. The script of Bakunin's dialectic, Cutler argues, gave the Alliance the purpose of providing the International with a true revolutionary organization.

The invisible dictatorship does not seem to have an autocratic intention in favor of Bakunin as an individual, but rather proposes a power shared by a professional cadre that monitors the mass organization so that it remains an instrument of Bakunin's political ideas. Bakunin argues that the "powerful but always invisible revolutionary collectivity" leave the full development [of the revolution] to the revolutionary movement of the masses and the most absolute freedom to their social organization,... but always taking care that this movement and this organization must never be able to reconstitute any authority, government or state and always fighting all collective ambitions (such as Marx's) [sic in the original], as well as individual ones, due to the natural influence, never official, of each member of our [International] Alliance [of Socialist Democracy]& #34;.

Anti-Semitism

In some of his writings, Bakunin espouses openly anti-Semitic views. Bakunin used the anti-Jewish sentiments that suggest the existence of a "Jewish" of global exploitation, saying the following:

This whole Jewish world, which comprises a single exploiting sect, a kind of people who suck blood, a kind of collective organic destructive parasite, which goes beyond not only the borders of States, but also of political opinion, is now, at least for the most part, at the disposal of Marx on the one hand, and of Rothschild on the other. [...] This may seem strange. What can be in common between socialism and a leading bank? The point is that authoritarian socialism, Marxist communism, demands a strong centralization of the state. And where there is a centralisation of the state, there must necessarily be a central bank, and where such a bank exists, the Jewish parasitic nation will be found, speculating with the work of the people.

Bakunin has been criticized for expressing these ideas, both by anarchists and non-anarchists.

Nationalism

In his pre-anarchist years, Bakunin's political thought was essentially a form of left-wing nationalism, specifically, a focus on Eastern European and Russian affairs. While Bakunin, at this time, located the national liberation and democratic struggles of the Slavs in a broader European revolutionary process, he did not pay much attention to other regions. This aspect of his thought dates from before he became an anarchist, and his anarchist works consistently envisioned a global social revolution, including both Africa and Asia. Bakunin as an anarchist continued to stress the importance of national liberation, but later insisted that this problem must be resolved as part of the social revolution. The same problem that (in his view) was pursued by the Marxist revolutionary strategy (the capture of the revolution by a small elite, which would then oppress the masses) would also arise in the independence struggles led by nationalism, unless that the working class and peasantry create anarchy.

I always feel the patriot of all oppressed countries. [...] Nationality is a historical, local fact that, like all real and harmless facts, has the right to claim general acceptance. [...] Each person, like every person, is involuntarily what he is and therefore has the right to be himself. [...] Nationality is not a principle; it is a legitimate fact, as is individuality. Every nationality, large or small, has the unquestionable right to be itself, to live according to its own nature. This right is simply the corollary of the general principle of freedom.Bakunin

When Bakunin visited Japan after his escape from Siberia, he was not really involved in its politics or with Japanese peasants. This could be taken as evidence of a basic disinterest in Asia, but on the other hand the context may lead one to give another interpretation. Bakunin stopped briefly in Japan as part of a rushed flight from twelve years in prison, a marked man running across the globe to his European home; he had no Japanese contacts and no Japanese language facility; the small number of foreign newspapers published by Europeans in China and Japan possibly provided no information about local revolutionary conditions or possibilities. Furthermore, Bakunin's conversion to anarchism came in 1865, towards the end of his life, and four years later. of his stay in Japan.

Works

He exposed his thought in a voluminous work, and it was his disciple James Guillaume who, between 1907 and 1913, in Paris, was in charge of compiling and editing all his books. Of the set of his willful work (the majority were left unfinished) the following stand out:

- Calling the Slavswhich denounces the bourgeoisie as an intrinsically antirevolutionary force and advocates the creation in Central Europe of a federation free of Slavic peoples

- God and the State

- Statism and Anarchy

- The principle of the State

- Criticism and Action

- The State and the commune

- Federalism, Socialism and Antitheology

There are also works that have been published in volumes:

- The Social Revolution in France. Two tones

- Writings of political philosophy. Two tomos. Compilation of G.P. Maksimov

- Take I. Criticism of society.

- Volume II. Anarchism and its tactics. With a biographical sketch of Max Nettlau

- Complete works. Five tones

In popular culture

In the Argentine film La odisea de los giles, by Sebastián Borenztein, based on the novel La noche de la usina by Eduardo Sacheri, reference is made to Bakunin since Fontana's character (played by Luis Brandoni) is an anarchist and he mentions it in one scene.

In the American series Lost, a character named Mikhail Bakunin (Lost) appears, played by the Venezuelan Andrew Divoff. This characterization may be based on the fact that the DHARMA project, which is mentioned in the series, had the purpose of founding a new utopian society free of exploitation. In addition, the character was born in kyiv, Ukraine, (former part of the Soviet Union). He was also a military doctor in Afghanistan, which is why similarities with the origin of the anarchist theoretician can be traced, and a clear reference to the model of anarchist society that he proposed.

The Madrid musical group Aviador Dro in their 1983 album Síntesis: La producción al poder dedicated the song «Comrade Bakunin» to him.

German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder frequently quotes Bakunin in his films. In the film Lola, the troubled anarchist Esslin (played by Matthias Fuchs) studies Bakunin in his spare time and quotes him in his meeting with his boss. In the film The Third Generation, the deserted soldier August (played by Volker Spengler) arrives with a suitcase stuffed with texts by Bakunin at one of the houses of the bourgeois terrorists and constantly reads passages from the texts to them. of the Russian anarchist. In one of the scenes, the terrorists take a Bakunin book from August and read sentences from the text while throwing the book at each other so that the deserted soldier cannot reach it.

- International Alliance of Socialist Democracy

- Colectivist anarchism

- I International

- Anarchism in Russia

Contenido relacionado

John Locke

Lev Shestov

Francis Bacon

Giorgio Agamben

John cage