Middle Ages

The Middle Ages, medieval period or Dark Ages is the historical period of Western civilization between the 5th and 15th centuries . Conventionally, its beginning is in the year 476 with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and its end in 1492 with the discovery of America, or in 1453 with the fall of the Byzantine Empire, a date that has the singularity of coinciding with the invention of the printing press —publication of the Gutenberg Bible— and with the end of the Hundred Years' War.

To this day, historians of the period prefer to nuance this break between Antiquity and the Middle Ages so that between the 3rd and 8th centuries it is customary to speak of Late Antiquity, which would have been a great transition stage in all areas: economically , for the replacement of the slave mode of production by the feudal mode of production; in the social sphere, for the disappearance of the concept of Roman citizenship and the definition of medieval estates; in the political sphere, for the decomposition of the centralized structures of the Roman Empire that gave way to a dispersion of power; and ideologically and culturally for the absorption and replacement of classical culture by theocentric Christian or Islamic cultures (each in its own space) .

It is usually divided into two great periods: Early or High Middle Ages (ss. v - x , without a clear differentiation with Late Antiquity); and the Late Middle Ages ( 11th - 15th centuries ), which in turn can be divided into a period of plenitude, the High Middle Ages ( 11th - 13th centuries ), and the last two centuries that witnessed the crisis of the 14th century .

Although there are some examples of previous use, the concept of the Middle Ages was born as the second age of the traditional division of historical time due to Christopher Cellarius ( Historia Medii Aevi a temporibus Constantini Magni ad Constaninopolim a Turcis captam deducta , Jena, 1688)Who considered it an intermediate time, with little value in itself, between the Ancient Age identified with the art and culture of the Greco-Roman civilization of classical Antiquity and the cultural renewal of the Modern Age —in which he places himself— beginning with the Renaissance and Humanism. The popularization of this scheme has perpetuated an erroneous preconception: that of considering the Middle Ages as a dark age, mired in intellectual and cultural retrogression, and secular social and economic lethargy (which in turn is associated with feudalism) .in its most obscurantist features, as defined by the revolutionaries who fought the Old Regime). It would be a period dominated by isolation, ignorance, theocracy, superstition and millenarian fear fueled by endemic insecurity, violence and the brutality of constant wars and invasions and apocalyptic epidemics .

However, in this long period of a thousand years there were all kinds of events and processes that were very different from each other, differentiated temporally and geographically, responding both to mutual influences with other civilizations and spaces and to internal dynamics. Many of them had a great projection towards the future, among others those that laid the foundations for the development of the later European expansion, and the development of the social agents that developed a predominantly rural-based stratified society but that witnessed the birth of an incipient urban life and a bourgeoisie that will eventually develop capitalism.Far from being a stagnant era, the Middle Ages, which had begun with migrations of entire peoples, and continued with great repopulation processes (Repopulation in the Iberian Peninsula, Ostsiedlung in Eastern Europe) saw how in its last centuries the old roads (many of them decayed Roman roads) were repaired and modernized with graceful bridges, and were filled with all kinds of travelers (warriors, pilgrims, merchants, students, goliards, etc.) embodying the spiritual metaphor of life as a journey ( homo viator ) .

New political forms also emerged in the Middle Ages, ranging from the Islamic caliphate to the universal powers of Latin Christianity (Pontificate and Empire) or the Byzantine Empire and the Slavic kingdoms integrated into Eastern Christianity (acculturation and evangelization of Cyril and Methodius ); and on a smaller scale, all kinds of city-states, from small German episcopal cities to republics that maintained maritime empires like Venice; leaving in the middle of the scale the one that had the greatest future projection: the feudal monarchies, which, transformed into authoritarian monarchies, prefigure the modern state.

In fact, all the concepts associated with what has been called modernity appear in the Middle Ages, in its intellectual aspects with the same crisis of scholasticism. None of them would be understandable without feudalism itself, if this is understood as a mode of production (based on the social relations of production around the land of the fief) or as a political system (based on personal power relations around the institution of vassalage), according to the different historiographical interpretations .

The clash of civilizations between Christianity and Islam, manifested in the rupture of the unity of the Mediterranean (fundamental milestone of the time, according to Henri Pirenne, in his classic Mohammed and Charlemagne ), the Spanish Reconquest and the Crusades; It also had its share of fertile cultural exchange (School of Translators of Toledo, Salernitana Medical School) that broadened the intellectual horizons of Europe, until then limited to the remains of classical culture saved by early medieval monasticism and adapted to Christianity.The Middle Ages made a curious combination between diversity and unity. Diversity was the birth of the incipient nations... Unity, or a certain unity, came from the Christian religion, which prevailed everywhere... This religion recognized the distinction between clerics and laity, so that it can be say that... marked the birth of a secular society. ... All this means that the Middle Ages was the period in which Europe appeared and was built .

That same Western Europe produced an impressive succession of artistic styles (pre-Romanesque, Romanesque and Gothic), which in the border areas were also mixed with Islamic art (Mudejar, Andalusian art, Arab-Norman art) or with Byzantine art.

Medieval science did not respond to a modern methodology, but neither had that of the classical authors, who dealt with nature from their own perspective; and in both ages without connection with the world of techniques, which was relegated to the manual work of artisans and peasants, responsible for a slow but constant progress in tools and production processes. The differentiation between vile and mechanical trades and liberal professions linked to intellectual study coexisted with a theoretical spiritual value placed on work in the Benedictine monasteries, an issue that was nothing more than a pious exercise, surpassed by the much more transcendent assessment of poverty, determined by the economic and social structure and expressed in medieval economic thought.

Medievalism is both the quality or character of medieval , as well as the interest in medieval times and themes and their study; and medievalist the specialist in these matters.The discredit of the Middle Ages was a constant during the Modern Age, in which Humanism, Renaissance, Rationalism, Classicism and Enlightenment assert themselves as reactions against it, or rather against what they understand it to mean, or against the traits of its own present that they try to disqualify as medieval survivals. However, since the end of the 16th century, interesting compilations of medieval documentary sources have been produced that seek a critical method for historical science. The Romanticism and Nationalism of the 19th century revalued the Middle Ages as part of their aesthetic program and as an anti-academic reaction (romantic poetry and drama, historical novel, musical nationalism, opera), as well as as the only possibility of finding a historical basis for the emerging nations (history painting, historicist architecture, especially neo-Gothic —restoring and recreating work by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc— and neo-Mudejar). The romantic abuses of the medieval setting (exoticism), produced already in the middle of the centuryxix the reaction of realism. Another type of abuses are those that give rise to an abundant pseudohistorical literature that reaches the present, and that has found the formula for media success by intermingling esoteric themes taken from more or less dark parts of the Middle Ages (Vatican Secret Archive, Templars, Rosicrucians, Freemasons and the very Holy Grail).Some of them were linked to Nazism, such as the German Otto Rahn. On the other hand, there is an abundance of other types of fictional artistic productions of varying quality and orientation inspired by the Middle Ages (literature, cinema, comics). Other medievalist movements have also developed in the 20th century: a serious historiographical medievalism, focused on methodological renewal (fundamentally due to the incorporation of the economic and social perspective provided by historical materialism and the Annales School) and a popular medievalism ( medieval shows, more or less genuine, as an update of the past in which the community identifies, what has come to be called historical memory ).

It is inappropriate to speak of the Middle Ages in other civilizations

The great migrations of the time of the invasions paradoxically meant a closure to the West's contact with the rest of the world. Europeans of the medieval millennium (both those of Latin Christianity and those of Eastern Christianity) had very little news that, apart from the Islamic civilization, which acted as a bridge but also as an obstacle between Europe and the rest of the Old World,Other civilizations developed. Even a vast Christian kingdom like that of Ethiopia, being isolated, became the cultural imaginary in the mythical kingdom of Prester John, barely distinguishable from the Atlantic islands of Saint Brandan and the rest of the wonders drawn in the bestiaries and the few , rudimentary and imaginative maps. The markedly autonomous development of China, the most developed civilization of the time (although turned inward and absorbed in its dynastic cycles: Sui, Tang, Song, Yuan and Ming), and the scarcity of contacts with it (the journey of Marco Polo, or the much more important expedition of Zheng He), which stand out precisely because of their unusualness and lack of continuity, do not allow us to call the 5th to 15th centuries of their history as medieval history., although it is sometimes done, even in specialized publications, more or less improperly .

The history of Japan (which during this period was in formation as a civilization, adapting Chinese influences to the indigenous culture and expanding from the southern islands to the northern ones), despite its greater remoteness and isolation, is paradoxically more often associated with the term mediaeval ; although such denomination is limited by historiography, significantly, to a medieval period that is located between the years 1000 and 1868, to adapt to the so-called Japanese feudalism prior to the Meiji era ( see also shogunate, han and Japanese castle ) .

The history of India or that of black Africa from the 7th century onwards had a greater or lesser Muslim influence, but they followed their own very different dynamics (Delhi Sultanate, Bahmani Sultanate, Vijayanagara Empire —in India—, of Mali, Songhay Empire —in black Africa—). There was even a notable Saharan intervention in the western Mediterranean world: the Almoravid Empire.

In an even clearer way, the history of America (which was going through its classic and post-classic periods) did not have any type of contact with the Old World, beyond the arrival of the so-called Viking colonization in America , which was limited to a reduced and ephemeral presence in Greenland and the enigmatic Vinland , or the possible subsequent expeditions of Basque whalers in similar areas of the North Atlantic, although this fact must be understood in the context of the great development of navigation in the last centuries of the Late Middle Ages, since headed for the Age of Discovery.

What did happen, and can be considered as a constant of the medieval period, was the periodic repetition of occasional Central Asian interference in Europe and the Near East in the form of invasions by Central Asian peoples, notably the Turks (Köktürks, Khazars, Ottomans) and the Mongols (unified by Genghis Khan) and whose Golden Horde was present in Eastern Europe and formed the personality of the Christian States that were created, sometimes vassals and sometimes resistant, in the Russian and Ukrainian steppes. Even on a rare occasion, the primitive diplomacy of the late medieval European kingdoms saw the possibility of using the latter as a counterweight to the former: the frustrated embassy of Ruy González de Clavijo to the court of Tamerlane in Samarkand, in the context of the Mongol siege of Damascus, a very delicate moment (1401-1406) in which Ibn Khaldun also intervened as a diplomat. The Mongols had already sacked Baghdad in a 1258 raid.

The beginning of the Middle Ages

Although several dates have been proposed for the beginning of the Middle Ages, of which the most widespread is the year 476, the truth is that we cannot locate the beginning in such an exact way since the Middle Ages are not born, but "it is done" as a result of a long and slow process that spans five centuries and that causes enormous changes at all levels in a very profound way that will even have repercussions to this day. We can consider that this process begins with the crisis of the third century, linked to the reproduction problems inherent in the slave mode of production, which required a continuous imperial expansion that no longer occurred after the fixing of the limesRoman. Possibly climatic factors also converged for the succession of bad harvests and epidemics; and in a much more evident way the first Germanic invasions and peasant uprisings ( bagaudas), in a period in which many brief and tragic imperial mandates follow each other. Since Caracalla, Roman citizenship had been extended to all free men of the Empire, showing that such a condition, previously so coveted, had ceased to be attractive. The Lower Empire acquires an increasingly medieval aspect from the beginning of the fourth century with the reforms of Diocletian: blurring of the differences between the slaves, increasingly scarce, and the settlers, free peasants, but subject to increasingly greater conditions of servitude , who lose the freedom to change their address, always having to work the same land; compulsory inheritance of public positions —previously disputed in close elections— and artisan trades, subject to collegiation —precedent of the guilds—, all to avoid tax evasion and the depopulation of cities, whose role as a center of consumption and commerce and as a link in rural areas is becoming less and less important. At least, the reforms manage to maintain the Roman institutional structure, although not without intensifying ruralization and aristocratization (clear steps towards feudalism), especially in the West, which is disassociated from the East with the partition of the Empire. Another decisive change was the implantation of Christianity as the new official religion by Theodosius I the Great's Edict of Thessaloniki (380) preceded by the Edict of Milan (313) with which Constantine I the Great rewarded the hitherto subversives for their providentialist aid in the battle of the Milvian Bridge (312),

No specific event —despite the abundance and concatenation of catastrophic events— determined by itself the end of the Ancient Age and the beginning of the Middle Ages: nor the successive sackings of Rome (by the Goths of Alaric I in 410, by the Vandals in 455, by Ricimer's own imperial troops in 472, by the Ostrogoths in 546), nor the terrifying irruption of Attila's Huns (450-452, with the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields and the strange interview with Pope Leo I the Great), nor the overthrow of Romulus Augustulus (last Roman emperor of the West, by Odoacer the chief of the Heruli -476-); they were events that his contemporaries considered the initiators of a new era. The culmination at the end of the 5th century of a series of long-term processes, including serious economic dislocation, the invasions and settlement of the Germanic peoples in the Roman Empire changed the face of Europe. For the next 300 years, Western Europe maintained a period of cultural unity, unusual for this continent, based on the complex and elaborate culture of the Roman Empire, which was never completely lost, and the establishment of Christianity. The classical Greco-Roman heritage was never forgotten, and the Latin language, undergoing transformation (medieval Latin), continued to be the language of culture throughout Western Europe, even beyond the Middle Ages. Roman law and multiple institutions continued to live, adapting in one way or another. What took place during this broad period of transition (which may be completed by the year 800, with the coronation of Charlemagne) was a kind of fusion with the contributions of other civilizations and social formations, especially the Germanic and the Christian religion. In the following centuries, even in the High Middle Ages, other contributions will be added, notably Islam.

Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries)

The Germano-Roman kingdoms (5th to 8th centuries)

Barbarians

The barbarians scatter furiously... and the scourge of the plague causes no less havoc, the tyrannical extortionist steals and the soldier plunders the riches and provisions hidden in the cities; A famine reigns so frightful that forced by it, the human race devours human flesh, and even mothers kill their children and cook their bodies to feed on them. The beasts fond of the corpses of those killed by the sword, by famine and by the plague, destroy even the strongest men, and fattening themselves on their members, they become more and more fierce for the destruction of the human race. In this way, with the four plagues exacerbated throughout the world: iron, famine, pestilence and wild beasts, the predictions made by the Lord through the mouth of his prophets come true. The provinces devastated... by the referred cruelty of the plagues,Hydatius,

Chronicon (c. 468) .

The text refers specifically to Hispania and its provinces, and the barbarians mentioned are specifically the Suevi, Vandals and Alans, who in 406 had crossed the limes of the Rhine (unusually frozen) at the height of Mainz and around 409 had reached to the Iberian Peninsula; but the image is equivalent in other times and places that the same author narrates, from the period between 379 and 468.

The Germanic peoples from Northern and Eastern Europe were at a stage of economic, social and cultural development obviously inferior to that of the Roman Empire, which they themselves perceived admiringly. In turn they were perceived with a mixture of contempt, fear and hope (retrospectively embodied in Constantine Cavafy 's influential poem Waiting for the Barbarians ), and were even attributed a vigilante role (albeit inadvertently) from a providential point of view by part of the Roman Christian authors (Orosio, Salviano de Marseille and San Agustín de Hipona). The denomination of barbarians (βάρβαρος) comes from the onomatopoeia bar-barwith which the Greeks mocked non-Hellenic foreigners, and which the Romans—barbarians themselves, though Hellenized—used from their own perspective. the term "barbarian invasions" was rejected by nineteenth- century German historians , a time when the term barbarism designated for the nascent social sciences a stage of cultural development lower than civilization and higher than savagery. They preferred to coin a new term: Völkerwanderung ("Migration of Peoples"), less violent than invasions , suggesting the complete displacement of a people with its institutions and culture, and more general even than Germanic invasions , including Huns, Slavs, and others.

The Germans, who had peculiar political institutions, in particular the assembly of free warriors ( thing ) and the figure of the king, were influenced by the institutional traditions of the Greco-Roman Empire and civilization, as well as that of Christianity (although not always of the Catholic or Athanasian Christianity , but from Arian ); and they gradually adapted to the circumstances of their settlement in the new territories, especially to the alternative between imposing themselves as a leading minority over a majority of the local population or merging with it.

The new Germanic kingdoms shaped the personality of Western Europe during the Middle Ages, evolving into feudal monarchies and authoritarian monarchies, and over time, giving rise to the nation-states that were built around them. Socially, in some of these countries (Spain or France), Germanic origin (Gothic or Frankish) became a trait of honor or caste pride held by the nobility as a distinction over the population as a whole.

The transformations of the Roman world

The Roman Empire had suffered from external invasions and terrible civil wars in the past, but by the end of the 4th century, the situation seemed to be under control. It had been a short time since Theodosius had again managed to unify both halves of the Empire under a single center (392) and established a new state religion, Nicene Christianity (Edict of Thessaloniki -380), with the consequent persecution of the traditional pagan cults and the Christian heterodoxies. The Christian clergy, converted into a hierarchy of power, ideologically justified an Imperium Romanum Christianum (Christian Roman Empire) and the Theodosian dynasty as it had already begun to do with the Constantinian one since the Edict of Milan (313).

The desire for political prominence of the richest and most influential Roman senators and those of the western provinces had been channeled. In addition, the dynasty had known how to channel agreements with the powerful military aristocracy, in which noble Germans enrolled who came to the service of the Empire at the head of soldiers united by ties of loyalty to them. Dying in 395, Theodosius entrusted the rule of the West and the protection of his young heir Honorius to General Stilicho, the eldest son of a noble Vandal officer who had married Flavia Serena, Theodosius' own niece. But when Valentinian III, grandson of Theodosius, was assassinated in 455, a large part of the descendants of those western nobles ( nobilissimus, clarissimus) who had so much confidence in the destinies of the Empire already seemed to distrust it, especially when in the course of two decades they had been able to realize that the imperial government secluded in Ravenna was increasingly prey to the exclusive interests and intrigues of a small group of senior officers of the italic army. Many of these were of Germanic origin and increasingly relied on the strength of their armed retinues of conventional soldiers and on the pacts and family alliances they might have with other Germanic chiefs installed on imperial soil together with their own peoples, which they developed more and more. plus an autonomous policy. The need to adapt to the new situation was evidenced by the fate of Gala Placidia, imperial princess held hostage by Rome's own plunderers (the Visigoth Alaric I and his cousin Ataulfo, whom he eventually married); or with that of Honoria, daughter of the former (in second nuptials with Emperor Constantius III) who chose to offer herself as wife to Attila himself, facing her own brother Valentinian.

Needing to maintain a position of social and economic predominance in their regions of origin, having reduced their estate assets to provincial dimensions, and aspiring to a political role that is typical of their lineage and culture, the honestiores(the most honest or honorable, those who have honor), representatives of the western late Roman aristocracies would have ended up accepting the advantages of admitting the legitimacy of the government of these Germanic kings, already highly Romanized, settled in their provinces. After all, these, at the head of their soldiers, could offer them far greater security than the army of the emperors of Ravenna. In addition, the provisioning of these troops was much less burdensome than that of the imperial ones, since they were largely based on armed retinues dependent on the Germanic nobility and fed from the provincial land heritage that they had appropriated for some time. Less burdensome both for provincial aristocrats as well as for groups of humiliores(the humblest, those lowered to the ground - humus -) who were grouped hierarchically around said aristocrats, and who, ultimately, were the ones who had been bearing the brunt of the harsh late-Roman taxation. The new monarchies, weaker and more decentralized than the old imperial power, were also more willing to share power with the provincial aristocracies, especially when the power of these monarchs was very limited within their people by a nobility based on their armed retinues, from their not too distant origin in the assemblies of free warriors, of which they were still primun inter pares .

But this metamorphosis of the Roman West into Roman-German had not been the consequence of an inevitability clearly evidenced from the beginning; On the contrary, the road had been hard, zigzagging, with attempts at other solutions, and with moments when it seemed that everything could go back to the way it was before. This was the case throughout the 5th century, and in some regions also in the 6th century as a consequence, among other things, of the so-called Recuperatio Imperii or Justinian's Reconquest.

The different kingdoms

The barbarian invasions since the third century had shown the permeability of the Roman limes in Europe, fixed on the Rhine and the Danube. The division of the Empire into East and West, and the greater strength of the Eastern or Byzantine Empire, determined that it was only in the western half where the settlement of these peoples and their political institutionalization as kingdoms took place.

The Visigoths, first as the Kingdom of Tolosa and then as the Kingdom of Toledo, were the first to carry out this institutionalization, taking advantage of their status as federates, obtaining a foeduswith the Empire, which entrusted them with the pacification of the provinces of Gaul and Hispania, whose control was practically lost after the invasions of 410 by Suevi, Vandals and Alans. Of the three, only the Suevi achieved definitive settlement in one area: the Kingdom of Braga, while the Vandals established themselves in North Africa and the islands of the Western Mediterranean, but were eliminated the following century by the Byzantines during the great territorial expansion of Justiniano I (campaigns of generals Belisario, from 533 to 544, and Narsés, until 554). Simultaneously, the Ostrogoths managed to settle in Italy, expelling the Heruli, who had in turn expelled the last Western emperor from Rome. The Ostrogothic Kingdom also disappeared in the face of Byzantine pressure from Justinian I.

A second group of Germanic peoples settled in Western Europe in the 6th century, among which the Frankish Kingdom of Clovis I and his Merovingian successors stood out, which displaced the Visigoths from Gaul, forcing them to move their capital from Toulouse (Toulouse ) to Toledo. They also defeated the Burgundians and Alemanni, absorbing their kingdoms. Somewhat later the Lombards settle in Italy (568-9), but they will be defeated at the end of the 8th century by the same Franks, who will reinstate the Empire with Charlemagne (year 800).

In Great Britain the Angles, Saxons and Jutes will settle, creating a series of rival kingdoms that will be unified by the Danes (a Nordic people) in what will end up being the kingdom of England.

Institutions

The Germanic monarchy was originally a strictly temporary institution, closely linked to the personal prestige of the king, who was no more than a primus inter pares(first among equals), elected by the assembly of free warriors (elective monarchy), usually for a specific military expedition or for a specific mission. The migrations to which the Germanic peoples were subjected from the 3rd century to the 5th century (boxed between the pressure of the Huns to the east and the resistance of the Roman limes to the south and west) gradually strengthened the figure of the king, while It came into increasing contact with Roman political institutions, which were accustomed to the idea of a political power that was much more centralized and concentrated in the person of the Roman Emperor. The monarchy was linked to the people of the kings for life, and the tendency was to become a hereditary monarchy, since the kings (as the Roman emperors had done) tried to ensure the election of their successor, most of the time still alive and associating them with the throne. The fact that the candidate was the firstborn male was not a necessity, but it ended up being imposed as an obvious consequence, which was also imitated by the other families of warriors, enriched by the possession of land and converted into noble lineages that were related to the ancient Roman nobility, in a process that can be called feudalization. Over time, the monarchy became patrimonial, even allowing the division of the kingdom among the king's sons. but it ended up being imposed as an obvious consequence, which was also imitated by the other families of warriors, enriched by the possession of land and converted into noble lineages that were related to the ancient Roman nobility, in a process that can be called feudalization. Over time, the monarchy became patrimonial, even allowing the division of the kingdom among the king's sons. but it ended up being imposed as an obvious consequence, which was also imitated by the other families of warriors, enriched by the possession of land and converted into noble lineages that were related to the ancient Roman nobility, in a process that can be called feudalization. Over time, the monarchy became patrimonial, even allowing the division of the kingdom among the king's sons.

Respect for the figure of the king was reinforced by sacralizing his inauguration (anointing with sacred oils by religious authorities and the use of distinctive elements such as an orb, scepter and crown, during an elaborate ceremony: the coronation) and the addition of religious functions (presidency of national councils, such as the Councils of Toledo) and thaumaturgical functions (royal touch of the kings of France for the cure of scrofula). The problem arose when the time came to justify the deposition of a king and his replacement by another who was not his natural successor. The last Merovingians did not rule by themselves, but through the positions of their court, among which the mayor of the palace stood out. Only after the victory against the Muslim invaders at the Battle of Poitiers was the steward Carlos Martel justified in arguing that the exercise legitimacy gave him sufficient merit to found his own dynasty: the Carolingian. On other occasions he resorted to more imaginative solutions (such as forcing the tonsure —ecclesiastical haircut— of the Visigoth king Wamba to incapacitate him).

The problems of coexistence between the Germanic minorities and the local majorities (Hispano-Roman, Gallo-Roman, etc.) were solved more effectively by the kingdoms with more projection in time (Visigoths and Franks) through the merger, allowing marriages mixed, unifying the legislation and carrying out the conversion to Catholicism against the original religion, which in many cases was no longer the traditional Germanic paganism, but the Arian Christianity acquired during its passage through the Eastern Empire.

Some characteristics of the Germanic institutions were preserved: one of them the predominance of customary law over the written law of Roman law. However, the Germanic kingdoms made some legislative codifications, with greater or lesser influence of Roman law or Germanic traditions, written in Latin from the 5th century (Theodorician laws, edict of Theodoric, Code of Euric, Breviary of Alaric). The first written code in the Germanic language was that of King Ethelbert of Kent, the first of the Anglo-Saxons to convert to Christianity (early 6th century). The Visigothic Liber Iudicorum (Recesvinto, 654) and the frank Salic Law(Clodoveo, 507-511) maintained a very long validity due to their consideration as sources of law in medieval monarchies and the Old Regime .

Latin Christianity and the Barbarians

The expansion of Christianity among the barbarians, the establishment of episcopal authority in the cities and of monasticism in rural areas (especially since the rule of Saint Benedict of Nursia —Montecassino monastery, 529—), constituted a powerful merging force of cultures and helped ensure that many features of classical civilization, such as Roman and Latin law, survived in the western half of the Empire, and even spread across Central and Northern Europe. The Franks converted to Catholicism during the reign of Clovis I (496 or 499) and thereafter spread Christianity among the Germans across the Rhine. The Suebi, who had become Arian Christians with Remismund (459- 469), converted to Catholicism with Teodomiro (559-570) due to the preaching of Saint Martin of Dumio. In this process they had gone ahead of the Visigoths themselves, who had previously been Christianized in the East in the Arian version (in the fourth century), and maintained for a century and a half the religious difference with the Hispano-Roman Catholics even with internal struggles within the class. dominant Gothic, as demonstrated by the rebellion and death of Saint Hermenegild (581-585), son of King Leovigild). Recaredo's conversion to Catholicism (589) marked the beginning of the merger of both societies, and of the royal protection of the Catholic clergy, visualized in the Councils of Toledo (presided over by the king himself). The following years saw a real and they maintained for a century and a half the religious difference with the Hispano-Roman Catholics even with internal struggles within the Gothic ruling class, as demonstrated by the rebellion and death of Saint Hermenegild (581-585), son of King Leovigild). Recaredo's conversion to Catholicism (589) marked the beginning of the merger of both societies, and of the royal protection of the Catholic clergy, visualized in the Councils of Toledo (presided over by the king himself). The following years saw a real and they maintained for a century and a half the religious difference with the Hispano-Roman Catholics even with internal struggles within the Gothic ruling class, as demonstrated by the rebellion and death of Saint Hermenegild (581-585), son of King Leovigild). Recaredo's conversion to Catholicism (589) marked the beginning of the merger of both societies, and of the royal protection of the Catholic clergy, visualized in the Councils of Toledo (presided over by the king himself). The following years saw a real visualized in the Councils of Toledo (presided over by the king himself). The following years saw a real visualized in the Councils of Toledo (presided over by the king himself). The following years saw a realVisigoth Renaissance with figures influenced by Saint Isidore of Seville (and his brothers Leandro, Fulgencio and Florentina, the four saints of Cartagena ), Braulio de Zaragoza or Ildefonso de Toledo, of great repercussion in the rest of Europe and in the future Christian kingdoms of the Reconquest ( see Christianity in Spain, monastery in Spain, Hispanic monastery, and Hispanic liturgy ). The Ostrogoths, on the other hand, did not have enough time to carry out the same evolution in Italy. However, the degree of coexistence with the papacy and Catholic intellectuals was evidence that the Ostrogothic kings elevated them to positions of greater trust (Boethius and Cassiodorus, both magister officiorumwith Theodoric the Great), but also of the vulnerability of his situation (executed the first -523- and separated by the Byzantines the second -538-). His successors in the dominion of Italy, the Lombard Arians, also failed to experience integration with the subject Catholic population, and their internal divisions meant that the conversion to Catholicism of King Agilulf (603) did not have major consequences.

Christianity was brought to Ireland by Saint Patrick at the beginning of the fifth century, and from there it spread to Scotland, from where a century later it returned through the north to an England abandoned by the Christian Britons to the pagan Picts and Scots (from from the north of Great Britain) and also to the pagan Germans from the continent (Anglos, Saxons and Jutes). At the end of the 6th century, under Pope Gregory the Great, Rome also sent missionaries to England from the south, making England Christian again within a century.

In turn, the Britons had begun an emigration by sea to the Brittany peninsula, even reaching places as far away as the Cantabrian coast between Galicia and Asturias, where they founded the diocese of Britonia. This Christian tradition was distinguished by the use of the Celtic or Scottish tonsure, which shaved the front part of the hair instead of the crown .

The survival in Ireland of a Christian community isolated from Europe by the pagan barrier of the Anglo-Saxons, caused a different evolution to continental Christianity, which has been called Celtic Christianity. They preserved much of the ancient Latin tradition, which they were able to share with continental Europe as soon as the wave of invasion had temporarily subsided. After its extension to England in the sixth century, the Irish founded in the seventh century monasteries in France, in Switzerland (Saint Gall), and even in Italy, the names of Columba and Columbanus being particularly prominent. The British Isles were for about three centuries the nursery of important names for culture: the historian Bede the Venerable, the missionary Boniface of Germany, the educator Alcuin of York, or the theologian John Scotus Erigena, among others. Such influence reaches the attribution of legends such as that of Saint Ursula and the Eleven Thousand Virgins, a Breton who would have made an extraordinary journey between Britain and Rome to end up martyred in Cologne.

Other medieval christianizations

For its part, the spread of Christianity among the Bulgarians and most of the Slavic peoples (Serbs, Moravians and the peoples of the Crimea and the Ukrainian and Russian steppes —Vladimir I of Kiev, year 988—) was much later, and in charge of the Byzantine Empire, with what was done with the orthodox creed (preaching of Cyril and Methodius, 9th century); while the evangelization of other Eastern European peoples (the rest of the Slavs —Poles, Slovenians and Croats—, Balts and Hungarians —Saint Stephen I of Hungary, around the year 1000—) and of the Nordic peoples (Scandinavian Vikings) he did for Latin Christianity starting from Central Europe, at a still later period (until the eleventh and twelfth centuries); allowing (especially the conversion of Hungary) the first overland pilgrimages to the Holy Land .It is madness to believe in gods.

Saga of Hrafnkell , priest of Frey (Iceland, composed in the late 13th century, but set in pre-Christian times) .

Khazars

The Khazars were a Turkic people from Central Asia (where the empire of the Köktürks had been formed since the 6th century) that in its western part had given rise to an important state that dominated the Caucasus and the Russian and Ukrainian steppes up to the Crimea in the seventh century. Its ruling class mostly converted to Judaism, a religious peculiarity that made it an exceptional neighbor between the Islamic caliphate of Damascus and the Christian empire of Byzantium.

The Byzantine Empire (4th to 15th centuries)

The division between East and West was, in addition to a political strategy (initially by Diocletian —286— and made definitive with Theodosius I —395—), a recognition of the essential difference between the two halves of the Empire. The East, very diverse in itself (Balkan peninsula, Mezzogiorno, Anatolia, Caucasus, Syria, Palestine, Egypt and the Mesopotamian border with the Persians), was the most urbanized part with the most dynamic and commercial economy, compared to a West in of feudalization , ruralized, with urban life in decline, slave labor increasingly scarce and the aristocracy increasingly alienated from the structures of imperial power and secluded in their luxurious villaeself-sufficient, cultivated by settlers in a regime similar to serfdom. The lingua franca in the East was Greek, as opposed to the Latin of the West. In the implantation of the Christian hierarchy, the East had all the patriarchates of the Pentarchy except that of Rome (Alexandria, Antioch and Constantinople, to which Jerusalem was added after the Council of Chalcedon in 451); even the Roman primacy (pontifical seat of Saint Peter) was a disputed fact because the Byzantine State operated according to Caesaropapism (begun by Constantine I and theologically founded by Eusebius of Caesarea) .

The survival of Byzantium did not depend on the fate of the West, while the opposite did: in fact, the eastern emperors chose to sacrifice Rome - which was no longer even the western capital - when they considered it convenient, abandoning it to its fate or even displacing the Germans (Heruli, Ostrogoths and Lombards) towards her, which precipitated her downfall. However, the Eternal City, which had symbolic value, was reconquered and included in the short-lived Exarchate of Ravenna.

Justinian's Imperial Restoration

Justinian I consolidated the border of the Danube and, from 532, he achieved a balance on the border with Sassanian Persia, which allowed him to shift Byzantine efforts towards the Mediterranean, rebuilding the unity of the Mare Nostrum : In 533, an expedition of General Belisarius annihilated to the Vandals (battles of Ad Decimum and Tricameron) incorporating the province of Africa and the islands of the Western Mediterranean (Sardinia, Corsica and the Balearic Islands). In 535 Mundus occupied Dalmatia and Belisarius Sicily. Narses eliminates the Ostrogoths from Italy in 554-555. Ravenna once again became an imperial city, where the lavish mosaics of San Vital will be preserved. Liberio only managed to displace the Visigoths from the southeastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula and from the Baetica province.

In Constantinople, two ambitious and prestigious programs were initiated in order to establish the imperial authority: one of legislative compilation: the Corpus iuris civilis , directed by Tribonian (promulgated between 529 and 534), and another constructive: the church of Santa Sofía, by the architects Antemio de Tralles and Isidoro de Mileto (built between 532 and 537). A symbol of classical civilization was closed: the Academy of Athens (529).Another, chariot racing remained a popular diversion that aroused passions. In fact, they were used politically, the color of each team expressing religious divergences (an early example of popular mobilizations using political colours). The Nika revolt (534) almost caused the emperor to flee, which Empress Theodora prevented with her famous phrase purple is a glorious shroud .

Crisis, survival and hellenization of the Empire

The 7th and 8th centuries represented a dark age for Byzantiumsimilar to that of the West, which also included a strong social and economic ruralization and feudalization and a loss of prestige and effective control of the central power. To the internal causes was added the renewal of the war with the Persians, nothing decisive but especially exhausting, which was followed by the Muslim invasion, which deprived the Empire of the richest provinces: Egypt and Syria. However, in the Byzantine case, the decrease in intellectual and artistic production also responded to the particular effects of the iconoclastic quarrel, which was not a simple theological debate between iconoclasts and iconodules, but an internal confrontation unleashed by the patriarchate of Constantinople, supported by Emperor Leo III,

The recovery of the imperial authority and the greater stability of the following centuries also brought with it a process of Hellenization , that is, of the recovery of the Greek identity as opposed to the official Roman entity of the institutions, which was more possible then, given the limitation and Geographical homogenization produced by the loss of the provinces, and which allowed a more easily managed and militarized territorial organization: the themes ( themata ) with the ascription to the land of the military established in them, which produced forms similar to Western feudalism.

The period between 867 and 1056, under the Macedonian dynasty, is known as the Macedonian Renaissance , in which Byzantium once again became a Mediterranean power, reaching out to the Slavic peoples of the Balkans and north of the Black Sea. Basil II Bulgarianwho occupied the throne in the period 976-1025 led the Empire to its maximum territorial extension since the Muslim invasion, occupying part of Syria, Crimea and the Balkans as far as the Danube. The evangelization of Cyril and Methodius will obtain a sphere of Byzantine influence in Eastern Europe that culturally and religiously will have a great future projection through the dissemination of the Cyrillic alphabet (adaptation of the Greek alphabet for the representation of Slavic phonemes, which is still used today ); as well as that of Orthodox Christianity (predominant from Serbia to Russia).

However, the second half of the eleventh century witnessed a new Islamic challenge, this time led by the Seljuk Turks and the intervention of the Papacy and Western Europeans, through the military intervention of the Crusades, the commercial activity of Italian merchants (Genoese , Amalfitans, Pisans and especially Venetians) and the theological controversies of the so-called Eastern Schism or Great Schism of East and West, with which the theoretical Christian aid was shown to be as negative or more so for the Eastern Empire than the Muslim threat. The process of feudalization was accentuated when the Komnenos emperors were forced to make territorial transfers (called pronoia ) to the aristocracy and members of their own family .

The spread of Islam (since the 7th century)

In the seventh century, after the preaching of Mohammed and the conquests of the first caliphs (both political and religious leaders, in a religion - Islam - that does not recognize distinctions between laity and clergy), the unification of Arabia had taken place and the conquest of the Persian Empire and much of the Byzantine Empire. In the 8th century, the Iberian Peninsula, India and Central Asia were reached (battle of Talas -751- Islamic victory over China after which that Empire was not deepened, but which allowed greater contact with its civilization, taking advantage of the knowledge of the prisoners). In the West, the Muslim expansion stopped after the battle of Poitiers (732) against the Franks and the mythical battle of Covadonga against the Asturians (722).

From the 8th century there was a slower spread of Islamic civilization as far afield as Indonesia and the African continent, and from the 14th century to Anatolia and the Balkans. Relations with India were also very close during the rest of the Middle Ages (although the imposition of the Mughal empire did not take place until the 16th century), while the Indian Ocean became almost an Arab Mare Nostrum , where the Adventures of Sinbad the Sailor (one of the Arabian Nights tales from the time of Harun al-Rashid).The commercial traffic of the sea and caravan routes linked the Indian Ocean with the Mediterranean through the Red Sea or the Persian Gulf and caravans from the desert. This so-called spice route (prefigured by the incense route in ancient times) was essential for bits of science and culture from the Far East to reach the West. To the north, the Silk Road fulfilled the same function, crossing the deserts and the Turkestan mountain ranges. Chess, Hindu-Arabic numerals and the concept of zero, as well as some literary works ( Calila e Dimna) were among the Hindu and Persian contributions. Paper, engraving or gunpowder, among the Chinese. The function of the Arabs, and of the Arabized Persians, Syrians, Egyptians and Spaniards (not only Islamic, since there were many who maintained their Christian or Jewish religion —not so much the Zoroastrian—) was far from being a mere transmission, as evidenced by the influence of the reinterpretation of classical philosophy that came through Arabic texts to Western Europe from Latin translations from the twelfth century, and the spread of crops and agricultural techniques throughout the Mediterranean region. At a time when they were practically absent from the European economy, commercial practices and monetary circulation in the Islamic world stood out, encouraged by the exploitation of gold mines as far away as those of sub-Saharan Africa,

The initial unity of the Islamic world, which had already been questioned religiously with the separation of Sunnis and Shiites, was also broken politically with the replacement of the Umayyads by the Abbasids at the head of the caliphate in 749, who also replaced Damascus by Baghdad as capital. Abderramán I, the last Umayyad survivor, managed to found in Córdoba an independent emirate for al-Andalus (Arabic name for the Iberian Peninsula), which his descendant Abderramán III converted into an alternative caliphate in 929. Shortly before, in 909, the Fatimids They had done the same in Egypt. Starting in the 11th century, very important changes took place: the challenge to Arab hegemony as the dominant ethnic group within Islam by the Islamized Turks, who would come to control different areas of the Middle East (Mamluks, Ottomans), or from Kurds like Saladin; the irruption of Latin Christians in three key points of the Mediterranean (Christian kingdoms of the Reconquest in al-Andalus, Normans in southern Italy and Crusaders in Syria and Palestine); and that of the Mongols from central Asia.Scholars like al-Biruni, al-Jahiz, al-Kindi, Abu Bakr Muhammad al-Razi, Ibn Sina, al-Idrisi, Ibn Bayya, Omar al-Khayyam, Ibn Zuhr, Ibn Tufail, Ibn Rushd, al-Suyuti, and thousands of other scholars were not an exception, but the general norm in Muslim civilization. The Muslim civilization of the classical period was remarkable for the large number of multifaceted scholars it produced. It is an example of the homogeneity of the Islamic philosophy of science, and its emphasis on synthesis, interdisciplinary investigations and the multiplicity of methods .Ziauddin Sardar

Al-Andalus (8th to 15th century)

Carolingian Empire (8th and 9th centuries)

Rise and rise

By the eighth century, the European political situation had stabilized. In the East, the Byzantine Empire was strong again, thanks to a series of competent emperors. In the West, some kingdoms ensured relative stability to various regions: Northumbria to England, the Visigothic Kingdom to Spain, the Lombard Kingdom to Italy, and the Frankish Kingdom to Gaul and Germany. In reality, the Frankish Kingdom was a composite of three kingdoms: Austrasia, Neustria, and Aquitaine.

The Carolingian Empire arises from the foundations created by the predecessors of Charlemagne from the beginning of the 8th century (Carlos Martel and Pepin the Short). The projection of its borders through a large part of Western Europe allowed Charles to aspire to rebuild the extension of the old Western Roman Empire, being the first political entity of the Middle Ages that was in a position to become a continental power. Aachen was chosen as the capital, in a central location and sufficiently far from Italy, which despite being freed from the domination of the Longobards and the theoretical Byzantine claims, retained a great autonomy that reached temporal sovereignty with the cession of some incipient Papal States (the Patrimonium Petrior Heritage of Saint Peter, which included Rome and much of central Italy). As a result of the close ties between the pontificate and the Carolingian dynasty, which had legitimized and defended each other for three generations, Pope Leo III recognized Charlemagne's imperial claims with a coronation under strange circumstances on Christmas Day 800.

The marks were created to set the borders against external enemies (Arabs in the Hispanic March, Saxons in the Saxon March, Bretons in the Breton March, Lombards —until their defeat— in the Lombard March and Avars in the Ávar March; later also one was created for the Hungarians: the Marca del Friuli). The interior territory was organized in counties and dukedoms (union of several counties or marks). The officials who directed them (counts, marquises and dukes) were watched over by temporary inspectors (the missi dominici—envoys from the lord—), and it was ensured that they were not inherited to prevent them from being patrimonialized in a family (something that, over time, could not be avoided). The appropriation of land together with the charges, intended above all the maintenance of the expensive heavy cavalry and the new battle horses ( chargers , introduced from Asia in the seventh century, which were used in a completely different way from the old cavalry, with stirrups, bulky chairs and that could support armor).Such a process was at the origin of the birth of the fiefdoms that had to be ceded to each soldier according to their rank, up to the basic unit: the knight who exercised lord over a territory, was left for his maintenance with a stately reserve and he left the meek ones for his serfs, who were obliged to cultivate the reserve with free work benefits in exchange for military protection and the maintenance of order and justice, which were the functions of the lord. Logically, fiefdoms at their different levels underwent the same patrimonial transformation as brands and counties, establishing a pyramidal network of loyalties that is the origin of feudal vassalage.

Charlemagne negotiated as equals with other great powers of the time, such as the Byzantine Empire, the Emirate of Córdoba, and the Abbasid Caliphate. Although he himself, as an adult, did not know how to write (which was common at the time, when only a few clerics did so), Charlemagne followed a policy of cultural prestige and a notable artistic program. He intended to surround himself with a court of wise men and start an educational program based on the trivium and the quadrivium , for which he called the intelligentsia of his time to his domain, promoting, with the collaboration of Alcuin of York, the so-called Renaissance Carolingian. Within this educational effort he ordered his nobles to learn to write, which he tried himself, although he never managed to do it fluently .

Division and sinking

Charlemagne died in 814, his son Ludovico Pío took power. His sons: Charles the Bald ( western France ), Louis the Germanic ( eastern France ) and Lothair I (eldest son and heir to the imperial title), clashed militarily, disputing the different territories of the empire, which, beyond aristocratic alliances , manifested different personalities, interpretable from a proto-national perspective (different languages: to the south and west, the Romance languages that began to differentiate themselves from Vulgar Latin prevailed, to the north and east the Germanic languages, as testified by the previous Strasbourg Oaths; own customs, traditions and institutions —Roman to the south, German to the north—). This situation did not end even in 843 after the Treaty of Verdun, since the later division of Lothair's kingdom among his sons (the Lotharingia, central strip from the Netherlands to Italy, passing through the Rhine region, Burgundy and Provence ) led their uncles (Carlos and Luis), to another distribution (the Mersen Treaty of 870) that simplified the borders (leaving only Italy and Provence in the hands of his nephew Emperor Louis II the Younger —whose position did not mean more primacy than honorific—but it did not lead to a greater concentration of power in the hands of those monarchs, weak and in the hands of the territorial nobility.In some regions, the pact was nothing more than an entelechy, since the North Sea coast was occupied by the Vikings. Even in theoretically controlled areas, subsequent inheritance and infighting between successive Carolingian kings and emperors subdivided and reunified territories in an almost random fashion.

The division, added to the institutional process of decentralization inherent in the feudal system, in the absence of strong central powers, and the pre-existing weakening of social and economic structures, meant that the next wave of barbarian invasions, especially those carried out by Hungarians and Vikings, plunge Western Europe back into the chaos of a new dark age.

Charles the Bald, King of West Francia .

Charles the Bald, King of West Francia . Apogee of the Carolingian Empire around 814.

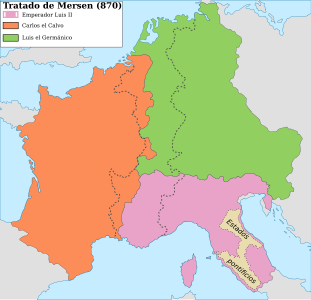

Apogee of the Carolingian Empire around 814. Divisions of the Empire in the treaties of Verdun (year 843, dotted line) and Meersen (870).

Divisions of the Empire in the treaties of Verdun (year 843, dotted line) and Meersen (870).Europe around 998.

Feudal system

Use of the term "feudalism"

The failure of Charlemagne's centralizing political project led, in the absence of that counterweight, to the formation of a political, economic and social system that historians have agreed to call feudalism, although in reality the name was born as a pejorative to designate the Old Regime. by its enlightened critics. The French Revolution solemnly abolished "all feudal rights" on the night of August 4, 1789 and "definitively the feudal regime", with the decree of August 11.

The generalization of the term allows many historians to apply it to the social formations of the entire western European territory, whether or not they belonged to the Carolingian Empire. Those in favor of a restricted use, arguing the need not to confuse concepts such as fiefdom, villae , tenure , or manor, limit it both in space (France, West Germany and North Italy) and in time: a «first feudalism» or «Carolingian feudalism» from the 8th century to the year 1000 and a «classical feudalism» from the year 1000 to 1240, in turn divided into two periods, the first, until 1160 (the most decentralized, in which each lord of castle could be considered independent, and the process called incastellamento occurs); and the second, that of the "feudal monarchy"). There would even be "imported feudalisms": Norman England from 1066 and the Latin states of the East created during the Crusades ( 12th and 13th centuries ) .

Others prefer to speak of "regime" or "feudal system", to subtly differentiate it from strict feudalism, or feudal synthesis , to mark the fact that features of classical antiquity mixed with Germanic contributions survive in it, involving both institutions and productive elements, and meant the specificity of Western European feudalism as a social economic formation compared to others that were also feudal, with transcendental consequences in the future historical evolution.There are more difficulties in the use of the term when we move further away: Eastern Europe experiences a process of "feudalization" since the end of the Middle Ages, just when in many areas of Western Europe the peasants are freed from the legal forms of serfdom, so that one usually speaks of Polish or Russian feudalism. The Old Regime in Europe, medieval Islam or the Byzantine Empire were urban and commercial societies, and with a variable degree of political centralization, although the exploitation of the countryside was carried out with social relations of production very similar to medieval feudalism.hydraulic despotism —Pharaonic Egypt, Indian kingdoms, or Chinese Empire—characterized by the taxation of peasant villages to a highly centralized state.In even more distant places the term feudalism has come to be used to describe an era. This is the case of Japan and the so-called Japanese feudalism, given the undeniable similarities and parallels that the European feudal nobility and their world has with the samurai and theirs. It has also been applied to the historical situation of the intermediate periods of the history of Egypt, in which, following a millennial cyclical rhythm, central power and life in the cities decline, military anarchy breaks the unity of the lands of the Nile, and the temples and local lords who manage to control a space of power rule in it independently over the peasants forced to work.

Vassalage and feud

Two institutions were key to feudalism: on the one hand, vassalage as a legal-political relationship between lord and vassal, a synallagmatic contract (that is, between equals, with requirements on both sides) between lords and vassals (both free men, both warriors). , both nobles), consisting of the exchange of support and mutual fidelities (endowment of positions, honors and lands —the fief— by the lord to the vassal and commitment of auxilium et consilium—military aid or support and political advice or support—), which if not complied with or broken by either of the two parties gave rise to a felony, and whose hierarchy was complicated in a pyramidal way (the vassal was in turn lord of vassals); and on the other hand, the fiefdom as an economic unit and of social relations of production, between the lord of the fiefdom and his serfs, not an egalitarian contract, but a violent imposition justified ideologically as a do ut des of protection in exchange for work and submission.

Therefore, the reality that is enunciated as feudal-vassal relations is really a term that includes two types of social relations of a completely different nature, although the terms that designate them were used at the time (and continue to be used) in an equivocal and with great terminological confusion between them:

Vassalage was a pact between two members of the nobility of different categories. The lowest-ranking knight became a vassal ( vassus ) of the most powerful nobleman, who became his lord ( dominus ) through Homage and Investiture, in a ritualized ceremony that took place in the keep of the lord's castle. The homage ( homage ) —from the vassal to the lord— consisted of prostration or humiliation —usually on his knees—, the osculum (kiss), the inmixtio manum —the hands of the vassal, joined in a prayerful position, were received between those of the lord— , and some phrase that he recognized to have become his man. After the homage, the investiture took place —from the lord to the vassal—, which represented the delivery of a fief (depending on the category of vassal and lord, it could be a county, a dukedom, a mark, a castle, a town, or a simple salary; or even a monastery if the vassalage was ecclesiastical) through a symbol of the territory or the food that the lord owes to the vassal —a bit of land, grass or grain— and the accolade, in which the vassal receives a sword (and a few blows with it on the shoulders), or a staff if he was religious.

The encomienda, encomendation or sponsorship ( patrocinium , commendatio , although it was customary to use the term commendatiofor the act of homage or even for the entire institution of vassalage) were theoretical pacts between the peasants and the feudal lord, which could also be ritualized in a ceremony or —more rarely— give rise to a document. The lord welcomed the peasants in his fiefdom, which was organized in a stately reserve that the serfs had to work compulsorily (sernas or corveas) and in the group of small family farms (mansos) that were attributed to the peasants so that they could they could survive. The lord's obligation was to protect them if they were attacked, and to maintain order and justice in the fiefdom. In exchange, the peasant became his serf and passed to the dual jurisdiction of the feudal lord: in the terms used in the Iberian Peninsula in the Late Middle Ages, the territorial lordship, that forced the peasant to pay rents to the nobleman for the use of the land; and the jurisdictional lordship, which made the feudal lord the ruler and judge of the territory in which the peasant lived, for which he obtained feudal income from very different sources (taxes, fines, monopolies, etc.). The distinction between property and jurisdiction was not something clear in feudalism, because in fact the very concept of property was confused, and the jurisdiction, granted by the king as a mercy, put the lord in a position to obtain the rents from him. There were no jurisdictional lordships in which all the plots belonged as property to the lord, with different forms of allodio among peasants being very widespread. In later moments of depopulation and which made the feudal lord the ruler and judge of the territory in which the peasant lived, for which he obtained feudal income from very different sources (taxes, fines, monopolies, etc.). The distinction between property and jurisdiction was not something clear in feudalism, because in fact the very concept of property was confused, and the jurisdiction, granted by the king as a mercy, put the lord in a position to obtain the rents from him. There were no jurisdictional lordships in which all the plots belonged as property to the lord, with different forms of allodio among peasants being very widespread. In later moments of depopulation and which made the feudal lord the ruler and judge of the territory in which the peasant lived, for which he obtained feudal income from very different sources (taxes, fines, monopolies, etc.). The distinction between property and jurisdiction was not something clear in feudalism, because in fact the very concept of property was confused, and the jurisdiction, granted by the king as a mercy, put the lord in a position to obtain the rents from him. There were no jurisdictional lordships in which all the plots belonged as property to the lord, with different forms of allodio among peasants being very widespread. In later moments of depopulation and The distinction between property and jurisdiction was not something clear in feudalism, since in fact the very concept of property was confused, and the jurisdiction, granted by the king as a mercy, put the lord in a position to obtain his rents. There were no jurisdictional lordships in which all the plots belonged as property to the lord, with different forms of allodio among peasants being very widespread. In later moments of depopulation and The distinction between property and jurisdiction was not something clear in feudalism, since in fact the very concept of property was confused, and the jurisdiction, granted by the king as a mercy, put the lord in a position to obtain his rents. There were no jurisdictional lordships in which all the plots belonged as property to the lord, with different forms of allodio among peasants being very widespread. In later moments of depopulation and being very generalized different forms of allodium in the peasants. In later moments of depopulation and being very generalized different forms of allodium in the peasants. In later moments of depopulation andrefeudalization , like the crisis of the 17th century, some nobles tried to have a manor be considered completely depopulated of peasants to free themselves from all kinds of restrictions and turn it into a round preserve that could be converted to another use, such as livestock .

Along with the fief, the vassal receives the serfs that are in it, not as slave property, but also not in a free regime; since his servile condition prevents them from abandoning him and forces them to work. The obligations of the lord of the fief include the maintenance of order, that is, civil and criminal jurisdiction ( mere and mixed empirein the legal terminology reintroduced with Roman Law in the Late Middle Ages), which gave even greater opportunities to obtain the productive surplus that peasants could obtain after work obligations —corveas or sernas in the manorial reserve— or payment of income —in kind or in money, of very little circulation in the High Middle Ages, but more generalized in the last medieval centuries, as the economy became more dynamic—. As manorial monopoly used to be the exploitation of forests and hunting, roads and bridges, mills, taverns and shops. All this was more opportunities to obtain more feudal income, including traditional rights, such as the ius prime noctisor right of pernada, which became a tax for marriages, a good example that it is in the surplus from which the feudal rent is extracted in an extra-economic way (in this case in the demonstration that a peasant community grows and prospers).

Feudal orders

Over time, following the trend marked by the Low Roman Empire, which was consolidated in the classical era of feudalism and which survived throughout the Old Regime, a society organized in a stratified manner was formed, in the so-called estates or orders (orders ): nobility, clergy and common people (or third estate): bellatores, oratores and laboratores the men who fight, those who pray and those who work, according to the vocabulary of the time. The first two are privileged, that is, the common law does not apply to them, but rather their own jurisdiction (for example, they have different penalties for the same crime, and their execution method is different) and they cannot work (they are prohibited from vile trades and mechanics), since that is the underprivileged condition . In medieval times, the feudal orders were not closed and blocked estates, but maintained a permeability that allowed in extraordinary cases social ascent due to merit (for example, the demonstration of exceptional courage), which were so rare that they were not they lived as a threat, something that did happen after the great social convulsions of the final centuries of the Late Middle Ages, in which the privileged were forced to institutionalize their position by trying to close access to their estates to the non-privileged (in which were not fully effective either). Completely inappropriate would be the comparison with the caste society of India, in which warriors, priests, merchants, peasants andoutcasts belonged to different castes understood as disconnected lineages whose mixing was prohibited.

The functions of the feudal orders were ideologically fixed by political Augustinianism ( Civitate Dei -426-), in search of a society that, although as a terrestrial society could not stop being corrupt and imperfect, could aspire to be at least a shadow of the image of a perfect "City of God" with Platonic roots in which everyone had a role in its protection, its salvation and its maintenance. This idea was reformulated and outlined throughout the Middle Ages, successively by authors such as Isidore of Seville (630), the school of Auxerre(Haimon of Auxerre -865- in the Burgundian abbey where Eric of Auxerre and his disciple Remigius of Auxerre worked, who followed the tradition of Scotus Eriugena), Boethius (892), Wulfstan of York (1010), Gerard of Cambrai ( 1024) or Adalberon of Laon; and used in legislative texts such as the so-called Huesca Compilation of the Fueros de Aragón (Jaime I), and the Siete Partidas (Alfonso X el Sabio , 1265) .

the bellatoresor warriors were the nobility, whose function was physical protection, the defense of all against aggression and injustice. It was organized in a pyramid from the emperor, through the kings and descending without interruption to the last squire, although according to its rank, power and wealth it can be classified into two different parts: high nobility (marquises, counts and dukes) whose fiefdoms have the size of regions and provinces (although most of the time not in territorial continuity, but distributed and diffuse, full of enclaves and exclaves); and the lower nobility or knights (barons, infanzones), whose fiefdoms are the size of small counties (at the municipal scale or less than municipal), or directly do not have territorial fiefdoms, living in the castles of the most important lords,regiment , that is, participating in their municipal government on behalf of the noble state ). At the end of the Middle Ages and in the Modern Age, when the nobility no longer exercised its military function, as was the case of the Spanish hidalgos, who claimed their estate privileges to avoid paying taxes and obtain some social advantage, boasting of their executory or coat of arms and manor house, but who did not have enough feudal income to maintain the noble way of life, they were in danger of losing their status by contracting an unequal marriage or earning a living by working:For the blood of the Goths,

and the lineage and the nobility

so grown,

by how many ways and ways

his great highness is lost

in this life!

Some, for little value,

for how low and downcast

they are;

others who, for not having,

with trades not due they are maintained.Copla X of the

Coplas on the death of his father by Jorge Manrique

In addition to religious legitimation, through secular culture and art (the epic of the chansons de geste and the lyric of courtly love of the Provençal troubadours) the ideological legitimation of the way of life, the social function and the the values of the nobility .

The orators or clerics were the clergy, whose function was to facilitate the spiritual salvation of the immortal souls: some formed a powerful elite called the high clergy (abbots, bishops), and others more humble, the low clergy (village priests or the brothers laymen of a monastery). The extension and organization of the Benedictine monasticism through the Order of Cluny, closely linked to the organization of the centralized and hierarchical episcopal network, with its apex in the Pope of Rome, established the double feudal pyramid of the secular clergy, destined to administer the of sacraments (which controlled the entire vital trajectory of the population, from birth to death); and the regular clergy, cut off from the worldand submitted to a monastic rule (usually the Benedictine rule). The three monastic vows of the regular clergy: poverty, obedience, and chastity; as well as the ecclesiastical celibacy that was imposed on the secular clergy, they functioned as an effective mechanism for linking the two privileged classes: the second sons of the nobility entered the clergy, where they were supported without constraints thanks to the numerous foundations, donations, dowries and testamentary mandates; but they did not dispute the inheritances with their brothers, who could keep the family patrimony concentrated. The lands of the Church remained as dead hands, whose function was to guarantee the masses and prayers provided by the donors, so that the children prayed for the souls of the parents.The confrontations were not lacking: the evidence of simony and Nicolaism (appointments of ecclesiastical positions interfered with by the civil authorities or their pure sale) and the use of the main religious threat to temporal power, equivalent to a civil death: excommunication. The Pope even attributed the authority to exempt the vassal from the fidelity due to his lord and claim it for himself, which was used on several occasions for the foundation of kingdoms that became vassals of the Pope (for example, the independence that Afonso Henriques obtained for the county converted into the kingdom of Portugal against the kingdom of León).

The laboratores or workers, were the common people, whose function was the maintenance of the bodies, the ideologically lower and humble function — humiliores were those close to humus , the earth, while their superiors were honestiores , those who could maintain honor or honor. Necessarily the most numerous, and the vast majority of them dedicated to agricultural tasks, given the very low productivity and agricultural yield, typical of the pre-industrial era and the very low technical level (hence the identification in Spanish of laboratorwith labrador). They were usually subject to the other estates. The common people were composed mostly of peasants, serfs of feudal lords or free peasants ( villains), and by artisans, who were scarce and lived either in the villages (those with less specialization, who used to share agricultural tasks: blacksmiths, saddlers, potters, tailors) or in the few and small cities (those with greater specialization and products of less pressing need or demanded by the upper classes: jewelers, goldsmiths, chandlers, coopers, weavers, dyers). The self-sufficiency of fiefdoms and monasteries limited their market and ability to grow. The construction trades (stonemasonry, masonry, carpentry) and the profession of master builder or architect are a notable exception: forced by the nature of their work to travel to the place where the building is built,trade secrets , which is at the origin of their distant and mythologized link with the secret society of Freemasonry, which from its origin considered them to be the primitive Freemasons .

The areas without intermediate dependence on noble or ecclesiastical lords were called royalengo and used to prosper more, or at least used to consider it a disgrace to become dependent on a lord, to the point that on some occasions they managed to avoid it with payments to the king, or The repopulation of border or depopulated areas was encouraged (as happened in the Asturian-Leonese kingdom with the depopulated Meseta del Duero) where mixed figures could appear, such as the villainous knight (who could maintain at least one war horse with his own farm and arm and defend himself) or the behetrías, who chose their own lord and could change from one to the other if it suited them, or with the offer of a charter or charter that granted a population its own collective lordship. The initial privileges were not enough to prevent most of them from falling into feudalization over time.