Mexican civilization

Them mexica (from Nahuatl: mexihkah ![]() [me felt] (?·i), “mexicas”), called in traditional historiography Aztecs, they were a Mesoamerican people of Nahua filiation that founded Mexico-Tenochtitlan. Towards the centuryXVIn the late Poscilla period, it became the center of one of the most extensive states that was known in Mesoamerica, settled in an islet to the west of the lake of Texcoco, on the central and southern margins of the lakes, as in Huexotla, Coatlinchan, Culhuacan, Iztapalapa, Chalco, Xico, Xochi On the islet is the current Mexico City, which corresponds to the same geographical location.

[me felt] (?·i), “mexicas”), called in traditional historiography Aztecs, they were a Mesoamerican people of Nahua filiation that founded Mexico-Tenochtitlan. Towards the centuryXVIn the late Poscilla period, it became the center of one of the most extensive states that was known in Mesoamerica, settled in an islet to the west of the lake of Texcoco, on the central and southern margins of the lakes, as in Huexotla, Coatlinchan, Culhuacan, Iztapalapa, Chalco, Xico, Xochi On the islet is the current Mexico City, which corresponds to the same geographical location.

Allied with other towns in the lake basin of the Valley of Mexico —Tlacopan and Texcoco—. The Mexicas subdued several indigenous populations that settled in the center and south of the current territory of Mexico, territorially grouped in Altépetl.

The Mexica are characterized by the exploitation of highly symbiotic crops —dependent on human manipulation, such as corn, chili, squash, beans, cocoa, etc.—; the extensive use of feathers to make clothing; the use of astronomical calendars —a ritual one of 260 days and a civil one of 365—; a sophisticated pre-Hispanic ornamental and military metallurgy based mainly on bronze, gold and silver.

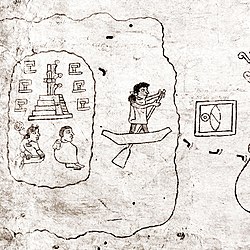

They had a script in the form of pictograms, used to document facts and calculations of architectural works based on their own metric system to measure land, comparable to other measurement systems of the Modern Age; the extensive use of products derived from cacti and agaves; and the treatment of igneous rocks (obsidian) for surgical and military purposes.

Introduction

The Mexica were the last Mesoamerican people to form a rich and complex religious, political, cosmological, astronomical, philosophical, and artistic tradition learned and developed by the peoples of Mesoamerica over many centuries.

Together with the Mayans, they are the most studied subject in Mesoamerican history, since documentary and archaeological sources are preserved, as well as numerous testimonies made mostly later by survivors of the Conquest of Mexico. They were the most powerful people on the continent before the arrival of the Spanish. This town developed important contributions to the world and to the agriculture that is currently known.

Background

The Mexica or Aztec period was one more phase of other cultures and archaeological periods, among which stand out:

- Olmecas (2 500 B.C.-200 AD): pyramid builders, the chiefs were kings-sacerdotes;

- Teotihuacán (400 B.C.-800 AD): there is the temple of the moon and the pyramid of the sun; its main god was Quetzalcóatl;

- Toltecas (900 d. C.-1168 d. C.): it had as capital Tula (Tollan-Xicocotitlan).

Phylogenetically, it is clear that the Nahuas speak languages related to the Uto-Aztec peoples of northern Mexico and the southern United States, and there is diverse evidence that they migrated towards the end of the 1st millennium AD. C. towards the south until reaching the center of Mexico. The Mexicas themselves collect this migration in various legendary stories, which may contain some real historical element, which explain the phases of their migration to the south.

Mexica mythology, being very diverse, but reinforced under the virtual mandate of Tlacaélel, located the mythical origin in Chicomóztoc (from Nahuatl: Chikomostok 'Place of the seven caves'), a site related to Aztlán —where the Aztec adjective comes from—, although there is no consensus on the exact location of the site because it is a mythical site. The language of the Mexicas was Classical Nahuatl, which is currently the indigenous language with the largest linguistic community in Mexico.

The ethnonym Aztec was popularized by researchers much later than his time. However, it is worth mentioning that the Mexicas did not call themselves that way, and that it was the result of a later misdesignation; and that later chronicles named them at all times as "Mexicans" or "those from Mexico."

Upon the arrival of the Spanish, the Mexica maintained tense relations with the subjugated Altépetl, to whom they imposed heavy tax burdens. This situation was taken advantage of by the newcomers in 1519, who quickly established alliances with the Zempoaltecas and the Tlaxcaltecas.

After the fall of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, the Mexica ruling elite was subdued and gradually integrated into colonial society, many of them regaining positions and privileges. The rest of the Mexica society suffered a series of collapses -mainly the demographic one- in all its structures, but there were many continuities and resistances that remained for a long time and until our days in the indigenous peoples of Mexico, although the bulk of the population it entered a process of a historic demographic drop in less than a century suffered by all indigenous peoples due to the new European diseases.

Terminology

In the historiography of Mesoamerica, the terms Nahuas, Mexicas and Aztecs appear as vaguely equivalent. However, they should not be taken as synonyms. These three terms appear when talking about the inhabitants who settled in the Anahuac Valley, mainly on the islet of Tenochtitlan during the 16th century /span>:

- The term nahua refers to all those who spoke or currently speak the Nahua language (náhuatl). During the invasion, the inhabitants of the Great Tenochtilan were mostly Nahuas; however, they were not the only ones of Mesoamerica. And there were Nahua enclaves all over Mexico City and even as far south as El Salvador, Nicaragua (Nicaraos) and Costa Rica (Nicoya).

- Nahuas living in the Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco areas were known as mexica because they called themselves mexihcah. The Spanish Chronicles of the CenturyXVI They changed the word and named them "Mexicans." This is how they appear in colonial history. However, the Nahuas of Texcoco and Tlacopan who participated as allies of the Mexicas and who are sometimes considered part of the Aztecs for having the same origin were called themselves acolhuas and tepanecas, respectively.

- Finally, since the centuryXIX Henceforth, most historians outside of Mexico have used the name or denomination azteca to refer to the mexicas (and often to their allies of the Triple Alliance). The name azteca refers to the myth narrated by the colonial chronicles, according to which "Mexicans, the Acolhuas[chuckles]required] and Tepanecas[chuckles]required] they had come out of a place called Aztlán."

In 1427 the Mexicas elect a new king, Izcóatl, who was the son of Acamapichtli, the first Mexica king, and a slave. This is the only case in which a man who did not have a woman of Toltec blood as his mother ascended the throne; The choice was surely due to the qualities of the candidate, whose military genius and political skill were to, in the thirteen years of his reign, transform the destiny of his people.

Due to the dispute between the sons of Tezozómoc, the different "governments in exile", caused by his conquests, understood that it was time to return to their different countries and free themselves from the yoke of Azcapotzalco. An alliance is then formed between the Mexica and various other groups. Of these, by far the most important is the one that represented the old Chichimeca dynasty that had reigned over Texcoco until the defeat of Ixtlilxochitl, which we have already related. The allies obtained the neutrality of some of the Tepanec cities and, after an extremely difficult war, Azcapotzalco itself was taken in 1428. This does not mark the end of the conflict, since Maxtla took refuge in Coyoacán and in more distant places, until finally he is definitively defeated in 1433. Then, Nezahualcóyotl can return to Texcoco and begins the long reign that was not to end until his death in 1472.

History

Origins

The origin of the Mexica is located among the Nahuatl-speaking groups of northern present-day Mexico and ancestors of those who settled during the so-called Chichimeca stage. Traditionally it was thought that there was a racial division between Aridoamerica —with mainly hunter-gatherer groups— and Mesoamerica, with sedentary peoples and farmers. From the most recent studies it is known that this was not the case and that ethnic diversity allowed many groups of Chichimeco origin to have different degrees of stratification and sedentary lifestyle, depending on the regional variants and the environmental conditions where they settled. For this reason, by having greater contact with Mesoamerican groups, they adopt civil ways and uses that they already had in some way in the north of present-day Mexico.

The Mexica are considered the last great Chichimeca migration to the Central Highlands, which is said to have occurred between the 12th and 13th centuries. The official Mexica myth states their mythical origin in Aztlán, an original island from where they left by divine designs. Historical evidence shows —with the exception of the hypotheses of Wigberto Jiménez Moreno and Paul Kirchhoff who place them on the island of Mexcaltitlán Nayarit or in the south of Guanajuato, respectively— that the idea of Aztlán responds, like many other Mexica symbolisms and diphrasisms, to a mythical and archetypal conception of the islet of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, in which the myth was already forged with the splendor of said city, in addition to the documentary sources mentioning an assimilation of the Mesoamerican from the early stages of migration. According to the mythical Mexica vision, the departure from the island was made in four or seven calpulli groups, of which the Huitznahuaque was the strongest, whose tutelary god was Huitzilopochtli, accompanied by the teomamaques or priests who carried the various tlaquimilolli (sacred bundles), which contained relics of the ancestors or various objects very sacred to the groups.

The Boturini Codex states the official route made by the Mexicas, which included sites in Hidalgo and Mexico; There are more than 30 sources that apparently indicate particular itineraries, these through the analysis are reduced to three main routes, so it is necessary to take into account in addition to Boturini those other two great traditions. The second derives from the Codex Mexicanus and the third from the Codex Telleriano-remensis.

The official mythical tradition must be seen through the way in which the ancient Mexicans created and wrote their history, to which they tried to insert religious and political elements, so it is necessary to separate its components and discern looking for the historical facts more plausible.

Arrival in the Basin of Mexico

Upon arriving in the Basin of Mexico, the Mexicas found a complex and settled political landscape, as well as the submission by the Tepanecas of Azcapotzalco to almost all the Altepetls; We can consider from the sources that their arrival is at the time of settling in the Xaltocan-Tzompanco region, most likely between 1226 and 1227. This seems to be the strongest historical moment from which their spread to the western shore of Lake Texcoco starts., until settling in Chapultepec approximately in 1280. After being expelled from Chapultepec (1299) by the altépetl of Azcapotzalco, Xaltocan, Culhuacan and Xochimilco, they settled in Tizaapan, territorial domain of Culhuacan, which they abandoned due to the harshness of the conditions and a confrontation with the Culhuas, going to the Texcoco region before choosing an islet where there were previous settlements, according to archaeological evidence.

According to the accepted official history, on an islet to the west of Lake Texcoco, the Mexicas founded Mexico-Tenochtitlan in the year 2 Calli or 1325 where, according to the official myth, the prophecy of an eagle devouring a snake was fulfilled on a nopal Now it is known that the Mexicas previously settled in various towns, they even founded some cities (such as Huixachtitlán), the information encoded in the documents reveals that they had already inhabited the islet since 1274. The final settlement included the acceptance of Azcapotzalco as supreme altepetl, paying tribute periodically and a general condition of obedience. The islet was grown with tulares, reeds and a rich aquatic diversity that will allow them subsistence as well as a strategic military position, although the first years their living conditions will be precarious.

The Mexica and war

The Mexica religion held that it was necessary to appease the gods with human sacrifices. For this reason, explains the historian Victor W. von Hagen:

"War and religion, at least for the Aztecs, were inseparable. They belonged to each other... In order to obtain appropriate prisoners-victims to sacrifice the gods, there were incessant small wars and even their armament was willing to incapacitate, not to kill, all to obtain food for the gods: blood and heart. ”

Territory

Mexico-Tenochtitlan was located on an islet to the west of Lake Texcoco, in the lacustrine zone of the Basin of Mexico. The Mexica culture occupied most of the center and south of the current Mexican Republic, it extended from the west of the Toluca Valley, covering almost all the states of Veracruz, Puebla, in the center, Hidalgo, Mexico, Morelos and Michoacán. only what is today the Municipality of Zitácuaro since there was an important border between the Tarascos and the Mexicas, in the south; a large part of the states of Guerrero and Oaxaca, as well as the Chiapas coast up to the border with Guatemala. However, the lordships of Meztitlán (in Hidalgo), Teotitlán and Tututepec (in Oaxaca), Purépechas (in Michoacán), Yopitzingo (in Guerrero) and Tlaxcala were outside their domain.

The Basin of Mexico is a geographical entity of more than 7800 square kilometers that is located in the southern part of the Central Highlands in the Republic of Mexico. It is a basin limited by chains of high mountains in the shape of an amphitheater, which had a lacustrine system in the middle made up of the Zumpango, Xaltocan, Texcoco, Xochimilco and Chalco lakes. Where the level was low and the waters fresh, as in the lakes of Xochimilco and Chalco, chinampero cultivation was possible. Between 2,270 and 2,750 meters above sea level, the somonte zone is included, whose fertile lands are favorable for the development of forests as well as for extensive agricultural practice. From 2,750 meters above sea level, the slopes are dominated by coniferous forests and populated by larger fauna. Despite being located south of the Tropic of Cancer, the Basin of Mexico had a temperate climate in pre-Hispanic times with average rainfall of 700 millimeters per year.

Status

The altépetl subjugated by the Mexica people did not form a unified political system but, rather, a system of tribute to Tenochtitlan. Among the Nahua peoples, the most important leader was called huey tlatoque ('great chief'), also known as huey tlatoani ('the who speaks').

After the formation of the Triple Alliance, the Mexica political model was definitively established as an elective monarchy. A council was in charge of choosing the huey tlatoani, who, once elected, was given absolute and unrestricted powers. However, it is suspected that a tlatoani huey, Tízoc, was poisoned by the council, for being considered inept and weak. It is noteworthy that religious and cosmogonic factors influence the formation of a tripartite government such as the Triple Alliance (where Mexico-Tenochtitlan had the greatest power and the largest proportional part of tributes) after the defeat of the Tepanec power and the submission of the Altépetl of Azcapotzalco, since it was not the first time that governments of this type were formed.

At the time Moctezuma Xocoyotzin governed another 38 altépetl paid tribute (according to the Mendoza Codex), where tribute was the central element of submission as well as the transfer of land where paid peasants (mayeques) worked and the product obtained went directly to the tlatoani; the acceptance of the main Mexica deity, the supply of men to the military contingents, the provisioning of the same to the step towards a campaign of conquest and settle political and legal issues in Tenochtitlan. For this reason, it is imprecise to speak of an empire, since Tenochtitlan did not seek a geographical extension per se or a state or national unity, but a greater allegation of resources and obedience to the huey tlatoani. Most of the altepetls preferred to pay tribute instead of receiving a military expedition that would burn their main temple and throw their deity down the steps (a symbol even represented iconographically in the codices of subjugation of an altepetl).

In the most important altépetl there was also a calpixque or collector who focused his activity on taxation. The altepetl who expressly accepted the Mexica domain were allowed to maintain their forms and administrative and political organizations as well as deities as long as they were under Huitzilopochtli. Only in important regions, containing other ethnic groups or where there was an open rebellion, did Mexica officials with tlatoani powers reside. For more than 50 years and until the appraisal made by the oidor Valderrama, this structure will remain with few changes in the indigenous towns of central New Spain.

City

Originally, Tenochtitlan was built on a small islet in the primitive Lake Texcoco that was successively artificially enlarged until it was joined to the islets of Tlatelolco, Nonoalco, Tultenco and Mixhuca, through hydraulic engineering of fills, piles and channels internal, as well as water container dams and bridges to reach about 13.5 square kilometers. There is no consensus on the population of Tenochtitlan, most historians give a conservative value between 80,000 to 230,000 inhabitants, larger than most of the European cities of its time, Constantinople (with 200,000 inhabitants), Paris (with 185,000) and Venice (with 130,000). Other historians give other estimates: Eduardo Noguera, based on old maps, calculates 50,000 houses and 300,000 inhabitants; Soustelle calculates 700,000 inhabitants by including the population of Tlatelolco and that of the islets and satellite cities in the area. Tlatelolco was originally an independent city from Mexica power, but was eventually subdued and turned into a suburb of Tenochtitlan.

Political organization

Government Institutions

The supreme authority in Mexico City-Tenochtitlan was a tlatoani (in Nahuatl tlahtoani 'orador'). The "Mexica empire" Called by his subjects Triple Alliance, it was initially a military alliance of three cities: Texcoco, Tlacopan and Tenochtitlan. In front of each of these there was a tlatoani who was the highest authority in that city. With the passage of time, the city of Tenochtitlan was prominent and in fact the other two became de facto subject to the orders of the tlatoani of Tenochtitlan, which is why it was called huēy tlahtoani ('great orator') to signal his position above the other two. This is the position that European historiography calls "Mexica emperor".

All tlatoani positions (Nahuatl tlahtoqueh or tlahtoanih) were hereditary positions. In addition to the tlatoanis there were the "nobles" (náhuatl pīpiltin) with many of whom the tlatoani had kinship relations. To that class frequently belonged the wife of the 'emperor'. The rest of society was made up of warriors, priests, and commoners (Nahuatl macehualtin).

Measuring methods

Using the Acolhua-Mexica codices with modern mathematics, the precision of the area values was evaluated, where the mathematical validity of the records in the codices is verified. The Acolhua-Mexica calculation methods had an error of less than 5% in 75% of the measured plots, while 85% of the measurements had only an error of less than 10%. In the codices, five recurring algorithms were detected that exactly reproduced the area in 78% of the registered plots.

These results indicate that the areas were calculated and not physically measured. Acolhua-Mexica arithmetic was functionally accurate in its cultural context, and its precision was compared with current measurement methods, thus proving a great accuracy of the results with a very low margin of error in most of the fields analyzed. The margin of error in 60% of the plots studied is negligible (<1%).

Advanced measurement and calculation

Other, more advanced calculation methods are still unknown, since only codices survive referring to lands of low economic value where the area was for tax allocation. It is suspected that more precise methods[citation needed] were used for Mexica engineering works, such as dikes, aqueducts, temples, etc. These unknown methods were necessary for the construction of structural elements which required an advanced calculation of their capacities, such as columns, walls, pipes, stairways, squares, among others. However, more precise measurements with smaller units were used for the creation of the most important sculptures in the ceremonial center of Tenochtitlan. Studies carried out on the Tlaltecuhtli Monolith show a design pattern which follows these units.

Accuracy of Mexica calculations

Apart from the side-by-side rule, the Surveyor's Rule was widely used, also developed by the Sumerians and used by the Romans where the area is the product of two averaged sides opposites.

A = (a + c)/2 x (b + d)/2.

According to studies that used this surveyor's rule, the large number of quadrilaterals with similar Ac (Recorded area in the codices) and Am (Calculated area) indicates that the tlacuilos chose algorithms to approximate the largest possible area in the boundaries of a given piece of land. This characteristic indicates that in order to reduce the tax burden, the Tlacuilos may have intentionally produced inaccurate measurements by systematically registering lower values in their linear measurements and areas. Other systematic errors were found when comparing them with a base 20, since this was the base of the Mesoamerican number system.

Reading of milcocollis and tlahuelmantlis

To obtain the values of the milcocollis (perimeter codes) the values of the sides of the measured lands were simply added, the unit used was the tlalcuahuitl (T). In the case of the tlahuelmantlis (area codes) the reading is more complex. The central glyphs are multiplied by the value 20 (since the areas were commonly registered in units of 20) to this result an additional value is added which is indicated in the upper right part of the terrain polygon; the result is the value of the land area in square tlalcuahuitl (T2). Some tlalhuemantlis showed a maize glyph within the terrain polygons, which indicated that the terrain was less than 400 T2.

Measurements of length

To measure distances, the Mexica used a group of units that were related to each other, among which the known measurements are the cemmatl (one hand), cemyollotli (one heart), cemomitl (one bone), cemacolli (one arm), cemmitl (one arrow). These symbols were used together with the annotation of other multiplier symbols of the number of times the object to be measured was worth, which were a vertical line that represented the unit, a group of 5 lines joined the first with the last with a horizontal line representing 5 units, a solid circle or banner (pantli) representing 20 units. The perimeters of lands were recorded in milcocollis (perimeter codices).

| Unit | Description | Approximate equivalent in the SI |

|---|---|---|

| Matlacicxitla | measuring 10 feet | 2,786 m |

| maitlneuitzantli | 3 rods | 2,508 m |

| Tlalcuahuitl | measuring wooden stick (3 rods) | 2,508 m |

| niquizantli | Vertical brace, 2.5 varas | 2.090 m |

| maitl | hand, horizontal brace, 2 rods | 1,672 m |

| cenequeztzalli | height of a peasant | 1.60 m |

| mitl | Venablo de Atlátl, 1.5 varas | 1,254 m |

| Yollotli | heart, 1 rod | 83.59 cm |

| ahcolli | shoulder | 77.5 cm |

| ciacatl | axila | 72.0 cm |

| tlacxitl | Step | 69.65 cm |

| Molicpitl | elbow, half rod | 41,80 cm |

| matzotzopaztli | forearm | 38.6 cm |

| omitl | bone | 33,44 cm |

| xocpalli | footprint | 27,86 cm |

| macpalli | palm of the hand, fourth, a room of rod | 20,90 cm |

| Canmiztitl | jeme | 18,0 cm |

| centlacol icxitl | half foot | 13,93 cm |

| Mapilli | finger of the hand | 1.74 cm |

Use of measurement units in monumental works

Teotihuacan

A repeated value of 0.83 m has been discovered in the city of Teotihuacán, corresponding to the Mexica “heart” yollotli. A railing of the Pyramid of Quetzalcóatl measures 1.66 m, where the archaeologist Sugiyama demonstrated that this measurement was applied systematically and correctly to the other buildings in the city.

Monolith of Tlaltecuhtli

Several multiples of yollotli are used in the Tlaltecuhtli Monolith discovered in the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlán; this monumental sculpture measures 4.17 m long (5 yollotli) or 20 fourths, and 3.62 m wide or 18 fourths. In addition, texts compiled by Bernardino de Sahagún show how Nahua units were used in traditional daily life

Palace of Nezahualcóyotl

The palace of Nezahualcóyotl was only documented by Alva Ixtlixóchitl and only its dimensions are mentioned, there are no milcocollis or tlahuelmantlis reporting its dimensions, only the accounts of Ixtlixóchitl where it expresses its dimensions in measurements of the Mexica metric system, which converted in the SI they are 1,031 km long, 0.817 km wide, with a diagonal of 1,316 km and a perimeter of 3,699 km. Only a basic description of the palace is found on the map or Quinatzin Codex.

Oztoticpac Palace

The palace of Oztoticpac, unlike the palace of Nezahualcóyotl, is fully documented with its dimensions, shape, and distribution. This uses milcocollis or tlahuelmantlis to describe the dimensions of its corridors, squares, and mansions, as well as including land attached to the palace.

Greater Temple of Tenochtitlan

The Templo Mayor in the Sacred Enclosure of Tenochtitlan, was also built according to the Mexica metric system. According to the archaeological remains in the streets of Mexico City and with the help of various reports after the conquest, it is believed that the Templo Mayor, in its seventh and last stage of construction, is 91 m long, 100 m wide with a diagonal of 135 m with a perimeter of 383 m.

Metallurgy in the Mexica Empire

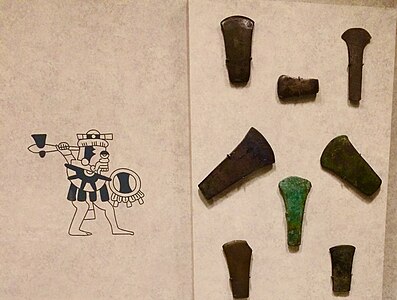

The use of metals in Mesoamerica is believed to date back to 800 B.C. C. with most of the evidence for it in western Mexico. Much the same as in the case of South America, precious metals are found more abundantly among the elites. In this area, a tradition specialized in metal alloys developed, which included, in addition to pure metals, alloys of precious metals with structural metals. High hardness tools were developed by alloying bronze with various metals, using cold work to increase its hardness. They also used the alloy of gold and silver added to bronze to give them ornamental tones, as well as to modify their sound properties in the various metallic instruments used by the Mesoamericans.

The exchange of technology and articles between the peoples of Ecuador and Colombia with western Mexico promoted development and research in both civilizations. Similar metallic artifacts have been found in these two regions: rings, needles, tweezers, axes, awls, knives and shields, which were made in a similar way and in contemporary historical contexts in both areas.

In addition to all these artifacts, of which specimens survive, there are many other objects and tools found only in the codices. Among these are the Tepoztli, the Amamalocotl and the metallic version of the Coa or Uictli. However, from the uictli and the Tepoztli specimens survive, but only the tips and heads of these respectively; These objects are in the Regional Museum of Guadalajara.

Collection of the Regional Museum of Guadalajara

The Regional Museum of Guadalajara in the state of Jalisco in Mexico, has one of the largest collections of metal objects from the Purépecha Empire. It has around 3,200 artifacts that come from the states of Jalisco, Michoacán, Colima and Nayarit. This collection was collected by Federico Solórzano.

| Artefacto | Amount | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Campanillas | 1934 | 60.5 |

| Open rings | 685 | 21.4 |

| Decoration axes/moneda | 186 | 5.8 |

| ornamental plates | 136 | 4.3 |

| Needles | 87 | 2.7 |

| Axes | 41 | 1.3 |

| Blinds | 42 | 1.3 |

| Puzones | 23 | 1 |

| Decorative Bells | 22 | 1 |

| Pins | 17 | 1 |

| Soils | 14 | 1 |

| Abalotes | 9 | 1 |

| Uictlis (Coas) or Azadas | 3 | 1 |

Purepecha Empire

Continuous contact between these civilizations kept the flow of ideas fostering the development of long-distance Andean trade lines, influence from areas further south seems to have reached the region and led to a second period (1200-1300 BC). until the arrival of the Spanish). By this time, bronze alloys were already widely used by metallurgists in western Mexico, especially the Purépecha Empire, partly because specific mechanical properties were needed for tools, weapons, and decorations. In some cases, the introduction of different metals to the alloy was with the aim of changing the tonality of the object or changing its resonance to improve its musical quality.

Items and techniques were imported from South America, but metallurgists in western Mexico began working ores from metals that were abundant in local deposits, the metal was not imported from South America. This technology also spread to the rest of Mesoamerica, where western Mexico had the best manufacturing in the area. Provenance studies on some artifacts from southern Mesoamerica made using the lost wax technique have shown that they were dissimilar to artifacts from the west, so a second point of metallurgical development could have been had since it has not been possible to identify it. the source.

- Bronze ax specimens

Mexica Empire

In the beginning, the Mexicas did not use metals in a massive way, even when they acquired objects from other civilizations. However, during its military expansion, the metallurgical technology present in the various dominated areas began to disperse throughout the empire. By the time of the conquest, it is believed that the use of bronze alloys was so common that in part of the daily life of the citizens of Tenochtitlan it was customary to give away bronze axes as a sign of social status and to gain favor within the hierarchical structure of the Mexica government

Musical instruments

A large number of bells, rattles and especially rattles have been found, where the latter were manufactured using the lost wax casting technique as seen in Colombia and also in most of Mexico. During this period copper was used almost exclusively.

Metallurgical Properties

Mesoamerican axes were made mainly of bronze in the Postclassic period, with very high Vickers hardness (VHN) values between 130 and 297 VHN for bronze alloys. Only the preclassic axes, which were older and more primitive, their value varied between 80-135 VHN.

The use of metallurgy in western Mexico via the sea route during the Classic period, since most of the objects found have been found near the coast. This technology appears to have been imported through the League of Merchants which traded objects as far south as Ecuador and as far north as Culiacán, Mexico. Objects from Ecuador and western Mexico show that these artifacts were found in contexts analogous archaeological sites, share identical chemical composition and manufacturing techniques and their designs are very similar.

The grain size of the metal alloy is variable throughout the object, showing intensive cold work by hammering its edges. This cold work treatment increases the hardness of the ax in this important part, leaving the rest of the structure softer so that it can resist the impacts of its daily use.

| Material | Value |

|---|---|

| Bronze Cu-Sn | 274HV |

| Bronze Cu-As-Sn | 297HV |

| Bronze Cu-As | 195HV |

| Stainless steel 347L | 180HV |

| Iron | 30–80HV |

Cultural aspects

Education

Universal education for children was compulsory until the age of fourteen. It was in the hands of their parents, but supervised by the authorities of their calpulli. Part of this education involved learning a collection of sayings, called huēhuetlàtolli ("sayings of the old"), which represented Aztec ideals.

There were two types of schools: telpochcalli, for practical and military studies, and calmécac, for specialized learning in writing, astronomy, theology, and leadership..

Religion

The Mexica religion was the synthesis of the ancient beliefs and traditions of the ancient Mesoamerican peoples, of a complexity that implied the very existence, the creation of the universe and the situation of the human being with respect to the divine, closely linked to agriculture and to the rain The human concert had its raison d'être in divine nature and implied various concepts, of which the Mexicas were the heirs of a Mesoamerican religious nucleus built over many centuries.

According to what was exposed by the scholar Alfredo López Austin, in the Mesoamerican conception matter was made up of an animated part —visible, tangible— and another with an internal charge with two forces, one bright, hot and dry and the other dark, cold and humid, similar to the notion of the cosmos (which synthesized a cosmogonic belief that the luminous part was the celestial vault up to the place where the sun dwelt —of a masculine/paternal characteristic, producer of fertile rain— and the dark part with the underworld —feminine/maternal recipient of the fertilizing rain and site of human and natural conception). The gods were integrated in a variety of ways by these two materials and maintained constant communication with humans, those who could "host" in mundane bodies intensely (turning the being inhabited into the god himself, as in the festivals in which a nobleman who was inhabited by Xipe Tótec was sacrificed) or lightly causing perversions or virtues.

These forces permeated everything inhabited on Earth and their balance characterized the micro and macrocosmic order, which had to be maintained. In the Mexica case, a solid priestly elite held the power of communication and balance as a form of ideological submission to the bulk of the population, neophyte in cosmogonic explanations. The religious festivals were intended to balance the creative will against the destructive or harmful and thus guarantee the continuity of the cycles, from the vital to the agricultural. It was not until the Postclassic peoples that the combination of these beliefs together with the necessary vital renewal and recycling of vital forces had in human blood the living expression of the ritual of continuity. For this reason, sacrifices were made either to humans invaded by divine forces and who were immolated in order to renew the powers of the "humanized" gods or in search of vital food (blood, or precious water, atl-tlachinolli) to ensure celestial transit. After Tlacaelel's reform, the Mexicas believed that blood was Tonatiuh's food, which was transported through the sky in two huge serpents. This belief is represented in the Stone of the Sun. In this connection it is worth mentioning that the political, religious and military elites practiced ritual anthropophagy with the sacrificial victims.

Quetzalcóatl was an ancient god, prior to the Mexica of which there are different versions: for some he was the creator of man, while for others he was a civilizing god. He is also known as the god of the wind under the name of Ehécatl, which is one of his forms, and another of his forms is the god of water and god of fertility. Quetzalcóatl is considered the son of the virgin goddess Coatlicue and twin brother of the god Xólotl. As an introducer of culture, he brought agriculture and the calendar to man, and is patron of arts and crafts. In a Mexica myth, the god Quetzalcóatl allowed himself to be seduced by Tezcatlipoca, but he threw himself onto a funeral pyre out of regret. After his death, his heart became the morning star, and as such he is linked to the divinity Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli. In any case, this god, described as a white-faced and bearded being, was a peaceful and civilizing god, opposed to human sacrifices, who tried to stop this ritual practice. Failing in his purpose, he migrated eastward, promising that one day he would return in a certain year from the Mexica count. The myth of Quetzalcóatl is very interesting to understand the Mexica's reaction to the arrival of the Spanish (Hernán Cortés).

Temple Mayor

In the center of the city was the Templo Mayor, a walled enclosure (with a snake-shaped wall, coatepantli) where the main temples and the Youth House (telpuchcalli) were located. Nearby was the palace of Axayácatl, which had 100 rooms with their own bathroom for visitors and ambassadors. It was there that Cortés's men stayed, along with their Tlaxcalan allies.

Moctezuma Xocoyotzin's palace had several annexes. One of them was the menagerie: two enclosures where animals from a large part of Mesoamerica were cared for. One enclosure was dedicated to birds of prey and the other to a wide variety of animals, including birds, reptiles, and mammals. About 300 people were in charge of caring for the animals. There was also a botanical garden dedicated especially to medicinal plants. Another section was a kind of aquarium, containing 10 saltwater ponds and 10 freshwater ponds for fish and waterfowl.

The canals were crossed by wooden bridges that were removed at night. It was trying to cross these channels at night that the invaders lost most of the gold they had stolen from Moctezuma's palace. The layout of the canals is still preserved in the layout of some avenues in current Mexico City such as México-Tacuba, Calzada del Tepeyac or Calzada de Tlalpan.

Arts

The Mexica people were good sculptors since they could make sculptures of all sizes in which they captured religious or nature themes. They captured the essence of what they wanted to represent and then executed their works in great detail. In the largest sculptures they used to represent gods and kings. The smallest were used for representations of animals and common objects. The Mexica used stone and wood and sometimes decorated the sculptures with colored paint or inlaid with precious stones.

Music, song and dance accompanied all ceremonies of a religious nature, marriages, funerals, sacrifices, those of a political nature such as the ascension of a new leader, those of a warrior nature and even festivities related to the calendrical cycles. Religious dances were performed in the courtyards of the temples. Some musical instruments used are Teponaztli, Tecomapiloa, Omichicahuaztli, Huehuetl, Coyolli, Chililitli, Chicahuaztli, Cacalachtli, Ayotl, Ayacahtli, Tetzilacatl, Ayoyotes. The tlapitzalli, a clay flute, was used to signal the start of a battle. Conch shells were also used as trumpets.

Mexican astronomy and astrology: the relationship between the stars and heavens

Without a doubt, the three stars that attracted the most attention to the Mexicas are: the sun, the moon and the planet Venus, for this reason these stars have caused great beliefs and myths. On the one hand they believed that the Moon was a god who had sacrificed himself and on the other that he was the son of Tlaloc. They thought the vaguely visible spots were made by rabbits. In the same way they attributed death and the reactivation of their environment, (for example: Vegetation, menstruation, etc.) Due to the way in which it "disappeared" and "reappeared". The Moon represented femininity, fertility, vegetation and also drunkenness, having as a symbol tecciztlì (the sea snail) which in turn is the symbol of the female reproductive system. When an eclipse occurred, they thought that the moon died, (for this reason it was a sacrificed god), and they represented it as a goddess in opposition to the Sun (male star). In ancient Teotihuacán they sacrificed men to the Sun and women to the moon. In certain aspects the moon is related to water, in the manuscripts it is represented in a crescent-shaped container filled with water, highlighting the silhouette of the rabbit on it.

The goddesses (such as the goddess of water) have not a few attributes in common, particularly in their clothing. The gods of drunkenness (being several, since there are several ways to get drunk) such as that of "pulque" were considered lunar divinities, since it was considered the cause of abundant harvests, turning the gods of drunkenness gods of the crops bountiful and banquet protection, veritable drink festivals to celebrate abundance. They were called Centzon Totochtin, the "four hundred rabbits”, however, when analyzing their names we realized that they refer to the names of a town, (eg Tepoztlán, a Nahua town in the Cuernavaca valley), this is explained since small local gods were grouped for each harvest and celebration. Undoubtedly the most important of the four hundred rabbits was Ometochtli "Two-rabbit". These gods were so important that several religious hymns were dedicated to them. When comparing what was previously said about the Sun and the Moon, it is possible to notice under both Astro the characteristics of the primordial couple, fire (sun) and Earth (moon); the very ancient duality represented in Heaven.

Venus

The planet Venus was called Hueycitlalin (the great star). In his god aspect (see Deity) he was Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli. Various manuscripts represent said god as an archer. He was feared as a cause of diseases and to avoid them care was taken to repair the cracks in the houses and close all openings in them when Venus was going to ascend the western horizon.

In another aspect (Borgia Codex plate 54, upper right) the god Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli appears in the funereal costume of the god of death, Mictlantecuhtli, with his face covered with a mask in the shape of a dead man's head. With this disguise, in addition to receiving the characteristics of a god that gives diseases and bad omens, he remembers that Venus was born from the death of Quetzalcóatl. After the sacrifice, Quetzalcóatl, turned into Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli, spent four days in the hell of the North, the domain of Mictlantecuhtli. Here is the theme of death and rebirth, of the trip to the country of death that unites the three personalities of Quetzalcóatl-Xólotl-Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli.

The observation of the movement of Venus gained great importance in astronomy and in indigenous Chronology. Seventy-five Venusian synodic cycles of 584 days are equivalent to 104 solar years, this period was called huehuetiliztli (old age). On the other hand, the Venusian synodic cycles were counted in groups of five (equivalent to 8 solar years). That is why Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli is usually represented with his face painted with five large white dots, two on each cheek and one on the nose.

The ancient Mexicans distinguished and knew numerous constellations. They especially observed the movement of the Pleiades (called in Nahuatl "Tianquiztli") every end of the “century”, that is, every 52 years. Its importance lies in the fact that if that movement continued at midnight, the world would not yet perish during the next period of 52 years. The Big Dipper is represented by Tezcatlipoca, in the form of a jaguar (ocelotl). Tezcatlipoca is also everything, the night sky where darkness reigns supreme, it synthesizes the gloomy and dark side of nature.

In general, all the stars were divided into two opposite groups: the Centzon Mimixcoa to the north and the Centzon Huitznáhuac to the south. The "Four Hundred Serpents of Clouds", small northern divinities, haunt the great steppe of cacti; the “Southern Four Hundred” are brothers of Huitzilopochtli, whom he killed at birth.

The thirteen heavens

The Aztecs had a basic structure of the Universe; As already mentioned, all the celestial bodies are divided into two groups: the Centzon Mimixcoa to the north and the Centzon Huitznahuac to the south; the four hundred serpents or four hundred meridionals, that is, the innumerable stars, and of Coyolxauhqui, the Moon, who were brothers of Huitzilopochtli, whom he killed at birth. And thirteen heavens are recognized (the number of heavens was fixed at thirteen because it is the great supreme number of the calendar), which were made up as follows:

- Ilhuícatl-Meztli: the stars;

- Ilhuícatl-Tetlalíloc: it is inhabited by the Tzimime, who are heavenly demons or feminine stars trying to prevent the sun from being born during the eclipses;

- Ilhuícatl-Tonatiuh: there are Tezcatlipoca (gods of the night and all material things) and those responsible for keeping the heavens;

- Ilhuícatl-Huitztlán: there are the souls of the sacrificed warriors who are transformed into precious birds;

- Ilhuícatl-Mamaloaco: that of the serpents of fire (the comets);

- Ilhuícatl-Yayauhco: the sky where winds are found in number four, one for each cardinal point;

- Ilhuícatl-Xoxoauhco: the one who shows his face in the day;

- Ilhuícatl-Nanatzcáyan: where the knives of obsidian crunch;

- Ilhuícatl-Teoiztac: white region;

- Ilhuícatl-Teocozáuhco: yellow region;

- Ilhuícatl-Teotlatláuhco: red region;

- Ilhuícatl-Teteocán: it is the place where the gods take faces;

- Ilhuícatl-Omeyocán: residence of Ometeotl, master of duality.

At a symbolic level, his vision of heaven can be interpreted as follows: the Sun born from a sacrifice crosses the sky from East to West, with his male and female entourage, passing through midday where he reigns, reaches the west and sinks into the home of the dead, where the world is surrendered to the fearsome powers of twilight and the arrows of Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli; only the moon shines as a symbol of fertility, and on the summit of the universe reigns the old primordial couple.

Researchers and scholars of Mexica culture

- CenturyXVI

- Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, Fray Toribio de Benavente ("Motolinia"), Fray Diego de Durán, Diego Muñoz Camargo, Fray Juan de Torquemada.

- CenturyXVII

- Hernando de Alvarado Tezozómoc, Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxóchitl, Francisco de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin, Juan Bautista Pomar, Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora

- CenturyXVIII

- Lorenzo Boturini Benaducci, Francisco Xavier Clavijero.

- CenturyXIX

- Alfredo Chavero, Manuel Gamio, Edward King Kinsborough, Antonio de León and Gama, Manuel Orozco and Berra, Francisco del Paso and Troncoso, Antonio Peñafiel..

- Twentieth and twenty-first century

- Robert Barlow, Frances Berdan, Ignacio Bernal, Woodrow Borah, Pedro Carrasco, Alfonso Caso, Víctor Manuel Castillo Farreras, Marco Antonio Cervera Obregón, Charles E. Dibble, Justino Fernández, Enrique Florescano, Ángel María Garibay Kintana, Ross Hassig, Joaquín Galarza, Paul Gendrop, Charles Gibson, Serge Gruzinski, Wigberto Jiménez Moreno

Contenido relacionado

Annex: Timeline of Microscope Development

October 26th

Cuzco