Metaphysics

Metaphysics (from the Latin metaphysica, and this from the Greek μετὰ [τὰ] φυσικά, "beyond nature") is the branch of philosophy that studies the nature, structure, components and fundamental principles of reality. This includes the clarification and investigation of some of the fundamental notions with which we understand the world, such as entity, being, existence, object, property, relationship, causality, time and space. Along with logic and epistemology, metaphysics is the most basic branch of philosophy. It has been studied by philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Boethius, Aquinas, Leibniz, Locke, etc.

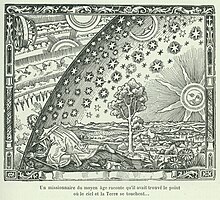

Before the advent of modern science, many of the problems that today belong to the natural sciences were studied by metaphysics under the title of natural philosophy. Today metaphysics studies aspects of reality that are inaccessible to investigation empirical. According to Immanuel Kant, metaphysical statements cannot be given in a priori synthetic judgments, which excludes metaphysics from becoming a positive science in the style of physics or mathematics. This will result in the XX to the Heideggerian reading of Western metaphysics as ontotheology and, therefore, to the need to rethink the question of being from the very origin of presocratic thinkers. Aristotle designated metaphysics as the "first science". In chemistry, the existence of matter is assumed, and in biology, the existence of life, but neither science defines matter or life; only metaphysics supplies these basic definitions.

Ontology is the part of metaphysics that deals with investigating which entities exist and which do not, beyond appearances. Metaphysics has two main themes: the first is ontology, which in Aristotle's words is the science that studies being as such. The second is teleology, which studies ends as the ultimate cause of reality. There is, however, a debate that continues today on the definition of the object of study of metaphysics, and on whether its statements have cognitive properties.

It is difficult to find an adequate definition of metaphysics. Over the centuries, many philosophers have held, in one way or another, that metaphysics is impossible. This thesis has a strong version and a weak version. The strong version is that all metaphysical statements are meaningless or meaningless. This of course depends on a theory of meaning. Ludwig Wittgenstein and the logical positivists were explicit advocates of this position. On the other hand, the weak version is that although metaphysical statements have meaning, it is impossible to know which are true and which are false, since this goes beyond the cognitive capacities of man. This position is the one held, for example, by David Hume and Immanuel Kant. On the other hand, some philosophers have argued that the human being has a natural predisposition towards metaphysics. Kant described it as an "inevitable necessity", and Arthur Schopenhauer even defined the human being as a "metaphysical animal".

Etymology

The word «metaphysics» derives from the Greek μετὰ φύσις, which means «beyond nature or beyond physics», comes from the title given by Andronicus of Rhodes (Siglo I BCE) to a collection of Aristotle's writings. This does not imply that metaphysics was born with Aristotle, but rather that it is in fact older, since there are cases of metaphysical thought in the pre-Socratic philosophers. Plato studied in various dialogues what being is, thus preparing the ground for Aristotle of Stagira, who developed what he called a "first philosophy", whose main objective was the study of being as such, its attributes and its causes.

The term «metaphysics» comes from the work of Aristotle composed of fourteen volumes (papyrus scrolls), independent of each other, which deal with various general themes of philosophy. These books are esoteric in nature, that is, Aristotle never conceived them for publication. Rather, they are a set of personal notes or notes on topics that he may have covered in class or in other systematic books.

The peripatetic Andronicus of Rhodes, when producing the first edition of Aristotle's works, ordered these books after the eight books on physics (μετὰ [τὰ] φυσικά). From there arose the concept of "metaphysics", which actually means: "what is on the shelf after physics", but which also in a didactic way means: "what follows explanations about nature" or "what that comes after physics”, understanding “physics” in its ancient meaning that referred to the study of φύσις, that is, of nature and its phenomena, not necessarily limited to the material plane.

In Antiquity the word «metaphysics» did not denote a particular discipline concerning the interior of philosophy, but rather the already mentioned compendium of Aristotle's scrolls. It is only from the [[XIII]] century that metaphysics becomes a special philosophical discipline whose object is the being insofar as it is. It is around that century when Aristotelian theories began to be known in the Latin West thanks to the influence of Muslim thinkers such as the Persian Avicenna and the Andalusian Averroes.

From then on, metaphysics became the highest philosophical discipline, thus reaching the Modern Age. Over time the word "metaphysics" acquired the meaning of "difficult" or "subtle" and in some circumstances it is used with a pejorative character, coming to mean "speculative, doubtful or non-scientific". In this sense, metaphysics is also considered a way of reflecting too subtly on any subject that runs between the dark and difficult to understand.

Definitions and concepts

In Aristotle's Metaphysics there are various definitions of metaphysics as a science. Metaphysics considered as "atheology" is the science of supreme causes (A, 1). As ontology it is the science of beings qua beings (G, 1). As theology it is the science of divine things (E, 1) and as "useology" it is the science of substance (Z, 1). Throughout history the positions regarding these definitions have been diverse. In fact, some consider that in Aristotle's Metaphysics there are four different metaphysics; while others think that the four definitions are integrated to form a single metaphysics. Metaphysics finds its unity in the following way: ontology and useology possess predicative universality, while ontology and useology are causally universal. In this way, the subiectum of metaphysics would be in the being as being, now the being is said primarily of the substance, for this reason the subiectum integrates the universal sciences by preaching. The principles of metaphysics come from the universal sciences by causality.

For Immanuel Kant, «Metaphysics is a speculative knowledge of reason, entirely isolated, which rises above the teachings of experience through mere concepts (not like mathematics, through their application to intuition), and where, therefore, reason must be its own disciple."

The Royal Spanish Academy defines metaphysics as the «part of philosophy that deals with being as such, and its properties, principles and first causes».

Objectives

Metaphysics asks about the last foundations of the world and of everything that exists. Its objective is to achieve a theoretical understanding of the world and of the most elementary general principles of what there is, because its purpose is to know the deepest truth of things, why they are what they are; and, even more, why they are.

Four of the fundamental questions of metaphysics are:

- What is being?

- What is it?

- Why is there something, and nothing else?

- Why am I in this world?

Then, one wonders not only what there is, but also why there is something. In addition, it aspires to find the most basic characteristics of everything that exists: the question raised is whether there are such characteristics that can be attributed to everything that is and if certain properties of being can be established with this.

Some of the main concepts of metaphysics are: being, nothing, existence, essence, world, space, time, mind, God, freedom, change, causality and end.

Some of the most important and traditional problems of metaphysics are: the problem of universals, the problem of the categorical structure of the world, and the problems linked to space and time.

Methods

Metaphysics proceeds in different ways:

- It is speculative, when it comes to a supreme principle, from which it interprets the whole of reality. A principle of this kind could be the idea, God, being, monad, universal spirit, or will.

- It is inductive, in its attempt to unifiedly consolidate the results associated with all the particular sciences, setting up a metaphysical image of the world.

- It is reductionist (not empirical-inductive, not speculative-deductive), when it is understood as a mere speculative construct based on budgets of which human beings have always had to leave in order to become known and to act.

Concepts

Being

Being is the most general of the terms. With the word "being" it is intended to encompass the real sphere in the general ontological sense, that is, the reality by antonomasia, in its broadest sense: "radical reality". The Being is, therefore, a transcendental, that which transcends and exceeds all the entities without being himself an entity, that is, without any entity, as wide as it is and is present, exhausts it. In other words: Being overwhelmed and dialectically overcomes the world of forms, the mundus asdpectabilis, moving in another context, "beyond the horizon of forms", beyond all "cosmic morphology".

The question for being does not correspond only to the West: already the ancient philosophers of China independently developed positions about being. Laozi in the sixth century BC makes the distinction between being and not-being. Then neo-Taoist schools (Wang Bi, Guo Xiang, etc.) will prevail the non-being over the being.

Tradition distinguishes two types of approaches other than the concept of being:

- The univocal concept of being: "being" is the most general characteristic of different things (called entities or entities), which remains equal to all the entities, after all the individual characteristics have been eliminated to the particular entities, that is: the fact that they "be", that is, the fact that they all belong to "being" (cf. ontological difference). This concept of “being” is the basis of the “metaphysics of essences”. The opposite of “being” is to be in this case the “essence”, to which the existence is simply added. In a sense, much of the concept of nothing is no longer differentiated. An example of this is given by certain texts of Thomas Aquinas' early philosophy (De ente et essentia).

- Analogical concept of being: “being” comes to be what can be attributed to “everything”, although in different ways (analogy) intis). Being is that, in what the different objects coincide and in what, in turn, are distinguished. This approach of being is the basis of a metaphysics (dialectic) of being. The opposite concept of being, is here nothing, since nothing can be out of being. The mature philosophy of Thomas Aquinas gives us an example of this understanding of “being” (Summa theologica)

Entity

Substance

The substance or substance (of the Greek: oασα, ousia) is a philosophical, metaphysical, ontological and theological term, originally used in the ancient Greek philosophy and later in the Christian theology, which refers to the being or essence of a thing, understood as what "underlies" or "under" the qualities or accidents, which exists in itself/by itself and which serves them as support. In this sense it is assumed that a characteristic of the substance is that it can remain the same as changing the qualities it bears; on the contrary, a change of the substance is a change to another substance.

It was used by several ancient Greek philosophers, such as Parmenides, Plato and Aristotle, as a primary designation for philosophical concepts of essence. In contemporary philosophy, it is analogous to English concepts to be and Contico. In Christian theology, the concept of θεα ουσα (Divine essence) is one of the most important doctrinal concepts, central to the development of trinitarian doctrine. The concept can be classified as monistic, dualistic or pluralistic varieties according to the number of substances that exist in the world. Monists argue that there is only one substance in the world (e.g., Spinoza pantheism). Dualism understands the world as composed of two fundamental substances (e.g. Cartesian dualism with res cogitans and the extensive). The pluralists maintain the existence of multiple substances (e.g., the theory of Plato forms, the hylemorphism of Aristotle and the monads of Leibniz).

The term comes from the Greek ousiathat translated into Latin as essentia or Substantia and, therefore, to Spanish and essence, entity, substance or substance and with expressions as true form or true nature of things.Category

In colloquial language, the degree of hierarchy within an order is understood by category, which can be:

- social: the place that occupies a particular person or institutional office, usually related to the exercise of power in all its fields:

- taxonomic: the level of importance of anything regarding all others.

Absolute

Branches

Ontology

The ontology (of the ancient Greek).ν [on] —genitivo).ντος— [onits], 'ent'; and λόγος [logos] 'science, study, theory') or general metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies what there is, as well as the relations between the entes (e.g., the relationship between a universal—such as red—and a particular cicuta)

Ontologists usually try to determine which are Category or higher and how they form category system which provides an inclusive classification of all entities. Commonly proposed categories include substances, properties, relationships, states of things and events. These categories are characterized by fundamental ontological concepts, such as particularity and universality, abstraction and concretion or possibility and necessity. Of special interest is the concept of ontological dependencewhich determines whether entities of a category exist at the level more fundamental. The disagreements within the ontology usually revolve around whether entities belonging to a particular category exist and, if so, how they relate to other entities.

Some ontological questions are: what is matter? What is a process? What is space-time? Are there emerging properties? Do all events fit any law(s)? Is there natural species? What makes an object real? Are there final causes? Is chance real? Many traditional questions of philosophy can be understood as ontological questions: Does God exist? Are there mental entities, such as ideas and thoughts? Are there abstract entities, such as numbers? Are there universals?

When used as a accounting noun, the terms "ontology" and "ontologies" do not refer to the science of beingbut the theories within the science of being. Ontological theories can be divided into several types according to their theoretical commitments. The monocategory ontologies they argue that there is only one basic category, which is rejected by polycategory ontologies. The hierarchical ontologies They claim that some entities exist at a more fundamental level and that other entities depend on them. The flat ontologiesInstead, they deny that privileged status to any entity.Teleology

Philosophical cosmology

The philosophy of space and time, also known as philosophic cosmology, is the branch of philosophy that deals with the aspects of ontology, epistemology and the nature of space and time.

The problems associated with space and time have traditionally been central to philosophical systems, from pre-democratic to Bergson and Heidegger. Analytical philosophy and logical positivism, in exercise of their critique of the traditional scientific method and metaphysics, have studied them with particular interest since their beginnings.Natural Theology

Rational Psychology

The rational psychology, also called the philosophy of man, metaphysical psychology or philosophical psychology, deals with the soul or mind of man.

History

Old Age

Since the beginnings of philosophy in Greece, with the so-called pre-Socratic philosophers, attempts to understand the entire universe from a unique and universal (original) principle, the αρχη (arche).

Parmenides of Elea (VI-V century BC) is considered the founder of ontology. It is he who uses the concept of being/entity in an abstract way for the first time. This metaphysical knowledge began when the human spirit became aware that what is real is not what our senses offer us, but what is captured by thought. (“It is the same thing to think and to be”) It is what he calls “being”, and which he characterizes through a series of conceptual determinations that are outside the data of the senses, as unborn, incorruptible, immutable, indivisible, one, homogeneous, etc. Parmenides exposes his theory with three principles: "being (or being) is and non-being is not", "nothing can pass from being to non-being and vice versa" and "thinking is the same as being" (The latter refers to the fact that what cannot be thought cannot exist). From his basic statement ("being is, non-being is not") Parmenides deduces that being is unlimited, since the only thing that could limit it is non-being; but since non-being is not, it cannot establish any limitation. Therefore, according to deduce Melisso de Samos, the being is infinite (limitless in space) and eternal (limitless in time). The influence of Parmenides is decisive in the history of philosophy and thought itself. Until Parmenides, the fundamental question of philosophy was: what is the world made of? (to which some philosophers had responded that the fundamental element was air, others that it was water, others a mysterious indeterminate element, etc.) Parmenides installed "being" (esse) on the scene as the main object of philosophical discourse. The next decisive step will be taken by Socrates.

Socrates (470-399 BC), on the other hand, focuses on morality. His fundamental question is: what is good? Socrates believed that if the concept of good could be extracted, people could be taught to be good (as mathematics is taught, for example) and evil would thus be eliminated. He was convinced that evil is a form of ignorance, a doctrine called moral intellectualism. He developed the first known philosophical technique: maieutics. It consisted of asking and asking again about the answers obtained over and over again, going deeper each time. With this he intended to reach the "logos" or the final reason that made one thing that thing and not another. This "logos" is the embryo of the "idea" of Plato, his disciple.

Plato (427-347 BC) places the central point of philosophy in the theory of Ideas. Plato observed that Socrates' logos was a series of characteristics that we perceive in objects (physical or not) and are associated with it. If we separate this logos from the physical object and give it formal existence, then it is called an “idea” (the word “idea” was introduced by Plato). In the Platonic dialogues Socrates appears asking what is fair, courageous, good, etc. The answer to these questions presupposes the existence of universal ideas knowable by all human beings that are expressed in these concepts. It is through them that we can capture the world in constant transformation. Ideas are the paradigm of things. His place is between being and non-being. They are prior to things, which participate (methexis) in them. In a strict sense, only they are. The particular things that we see only represent more or less exact copies of the ideas. The determination or definition of the ideas is obtained through a rigorous dialogic exercise, framed in a certain historical and conjunctural context, delimiting what the research has focused on (the idea). With the theory of Ideas Plato intends to prove the possibility of scientific knowledge and impartial judgment. The fact that all human beings have the possibility of accessing the same knowledge, both in the field of mathematics and in ethics, is explained through the theory of «memory» (ἀνάμνησις), according to which we remember the eternal ideas that we knew before our birth. With this, Plato explains the universality of the rational capacity of all human beings, confronting some of his contemporaries who maintained the inability to access knowledge by slaves or non-Hellenic peoples, among others. The postplatonic tradition often understood Plato's theory of Ideas in the sense that it would have assumed an existence of ideas separate from the existence of things. This theory of the duplication of worlds, in the Middle Ages led to the controversy about universals.

Aristotle (384-322 BC) never used the word “metaphysics” in his work known as Metaphysics. This title is attributed to the first systematic editor of the Stagirite's work, Andrónico de Rodas, who assumed that, due to their content, the fourteen books that he grouped together should be placed after "physics" and for that reason he used the prefix " μετὰ» (beyond... or after...) Metaphysics, according to Aristotle, is first, a theory of the general principles of thought (which he addresses in more detail in his logic); and secondly, a doctrine (logos) of being (on) as such. Aristotle's metaphysics revolves around two fundamental questions: that of the beginning and that of unity. In his analysis of beings, Aristotle goes beyond matter, studying the qualities and potentialities of what exists to end up speaking of "first being", the "immobile motor" and unmoved generator of all movement, who would later be identified with God. For Aristotle, metaphysics is the science of the essence of entities and the first principles of being. Being is said in many ways and these reflect the essence of being. In this sense, he elaborates being, independently of the momentary, future and casual characteristics. The ousía (generally translated as substance) is that which is independent of the characteristics (accidents), while the characteristics are dependent on the ousía. The ousia is what exists in itself, as opposed to the accident, which exists in another. Grammatically or categorically, it is said that the substance is that to which characteristics are attached, that is, it is that about which something can be affirmed (predicated). What is stated about the substances are the predicates. To the question of what would ultimately be the essence that remains immutable, Aristotle's answer is that the ousía is a determining form –the eidos- is the origin of everything. to be, that is to say, that for example in the eidos of Socrates, what in his human form, determines his humanity. And also the one that determines that man being free by nature and not being a free slave, determines that the slave is a constitutive part of his master, that is, that he is not only his master's slave at a certain juncture and from a certain perspective, but who is a slave by nature.

Middle Ages

In the Islamic world, the arrival of Greek philosophy was not direct, but has to do with the Christian monasteries in the Arabian peninsula and those belonging to ideologies considered heretical that used Greek philosophy not as an end, but as an instrument that served them for their theological speculations (like the Monophysites or the Nestorians). It is due to the practical interest in Greek medicine that translations into Persian began to be made, which later would later be transferred to Arabic. It is worth mentioning that in Arabic there is no verb "to be" and more hardly a construction like "to be", which is a turned into a noun. The metaphysics of the Islamic world was greatly influenced by the metaphysics of Aristotle.

In the Christian world, after the "rediscovery" of Aristotle's Metaphysics in the mid-XII century, many scholastics wrote comments on this work. The problem of universals was one of the main problems involved during that period. Other topics include:

- Hilomorphism: development of the aristotelian doctrine that individual things are a compound of material and form

- Existence and essence

- Causality: the discussion on causality consisted mainly of comments about Aristotle, mainly about physical works, About heaven and About generation and corruption. The focus of this thematic area was only medieval, the rational research of the universe was seen as a way of approaching God

Metaphysics came to be considered the "queen of the sciences" (Thomas Aquinas), although there was also debate about the distinction and order of hierarchy between metaphysics and theology, especially in scholasticism. The question of the distinction between metaphysics and theology would also be omnipresent in modern philosophy.

The medieval scholastics set themselves the task of reconciling the tradition of ancient philosophy with religious doctrine (Muslim, Christian or Jewish). Based on late Neoplatonism, medieval metaphysics proposes to recognize the "true being" and God from pure reason.

The central themes of medieval metaphysics are the difference between the earthly being and the celestial being (analogy entis), the doctrine of transcendentals and the proofs of the existence of God. God is the absolute foundation of the world, which cannot be doubted. It is discussed whether God created the world out of nothing (creation ex nihilo) and whether it is possible to access knowledge of him through reason or only through faith. Inspired by the theory of the duplication of worlds attributed to Plato, his metaphysics manifests itself as a kind of "dualism" of "here" and "beyond", of "mere sensible perception" and "pure thinking as rational knowledge". », of an «immanence» of the inner life and a «transcendence» of the outer world.

René Descartes was one of the greatest exponents of metaphysics in the Middle Ages (although Descartes lived in the Modern Age). Descartes built a metaphysical thought talking about issues such as existence, substance and God. Descartes defines metaphysics as the roots of knowledge if it were a tree, the trunk being physics and natural philosophy and the branches being the mechanical arts. Descartes speaks about the substance as that which can exist by itself without the need for anything else, affirms the existence of the thinking substance (res cogitans) and the extensive substance (res extensa), this being the substantial dualism apart from the existence of the infinite substance (God).

In his text called "Metaphysical Meditations" René considers that he can only believe what is indubitable, in other words, everything that can be doubted is false. Starting from that idea:

- Find that he exists (Cogito ergo sum).

- It proves that God exists from solipsism.

- It proposes the existence of an Evil Genius who makes him believe false ideas.

- It again proves the existence of God from an ontological argument.

- It shows the existence of the material and that there is a soul and a body.

Main article: Metaphysical Meditations.

Modern Age

The modern tradition divides metaphysics into: general metaphysics or ontology —the science of beings as beings— and special metaphysics, which is divided into three branches:

- Philosophy of nature, also called rational cosmology or simply cosmology

- Philosophy of man, also called metaphysical psychology, philosophical psychology, rational psychology, metaphysical anthropology or philosophical anthropology

- Natural theology, also called theodicea or rational theology

This classification, which was proposed among others by Christian Wolff, has been later disputed, but is still considered canonical.

Kant's transcendental idealism marked a "Copernican turn" for metaphysics. His position towards metaphysics is paradigmatic. He attributes it to being a discourse of "hollow words" without real content, accuses it of representing the "hallucinations of a psychic", but on the other hand he picks up on her the demand for universality. Kant set out to found a metaphysics "that can be presented as a science." For this he first examined the very possibility of metaphysics. For Kant, the ultimate issues and the general structures of reality are linked to the question of the subject. From this budget he deduced that we must study and judge what can be known by us. Through his criticism, he explicitly differentiated himself from philosophical positions that have as their object the question of what knowledge is. He thus distanced himself from the prevailing philosophical tendencies, such as empiricism, rationalism and skepticism. Also through his criticism, he distanced himself from the dogmatism of metaphysics, which -according to Kant- had become a series of statements on issues that go beyond human experience. He then tried to carry out a detailed analysis of the human faculty of knowing, that is, a critical examination of pure reason, of reason unrelated to the sensible ( Critique of pure reason , 1781- 1787). For this, Kant's epistemological assumption is decisive that reality does not appear to the human being as it really is (in itself), but as it appears to him due to the specific structure of his faculty of knowledge. As scientific knowledge also always depends on experience, man cannot make judgments about things that are not given by sensations (such as «God», «soul», «universe», «everything», etc.) For this reason Kant deduced that traditional metaphysics is not possible, because the human being does not have the ability to form a concept based on the sensitive experience of the spiritual, which is the only one that would allow the verification of metaphysical hypotheses. Since thinking has no knowledge of reality in this regard, these issues will always remain in the speculative-constructive realm. So, in principle, according to Kant it is not possible to rationally decide central questions such as whether God exists, whether the will is free or whether the soul is immortal. Mathematics and physics can formulate synthetic judgments a priori and, therefore, achieve universal and necessary knowledge, scientific knowledge.

From Kant's transcendental idealism arises German idealism —represented above all by Fichte, Schelling and Hegel— which considers reality as a spiritual event in which the real being is overcome, being integrated into the ideal being. German idealism picks up Kant's transcendental turn, that is, instead of understanding metaphysics as the search for obtaining objective knowledge, it deals with the subjective conditions of possibility of such knowledge. Thus, it arises to what extent the human being can come to recognize this evidence. However, he rejects that knowledge is limited to possible experience and mere phenomena, and proposes an overcoming of this position, returning to metaphysical postulates that can claim universal validity: "absolute knowledge" as it was said from Fichte to Hegel. If we accept that the contents of knowledge are only valid in relation to the subject —as Kant supposed— and we consider that this perspective is absolute, that is, it is the perspective of an absolute subject, then valid knowledge for this absolute subject also has absolute validity.. From this approach, German idealism considers that it can overcome the empirical contradiction between subject and object, in order to grasp the absolute.

Hegel maintains that from a pure and absolute identity a difference cannot arise or be understood (such an identity would be like «the night, in which all the cows are black»): it would not explain reality in all its diversity. That is why "the identity of the absolute" must be understood as existing from its origin, since it contains within itself the possibility and the necessity of a differentiation. This implies that the absolute is realized in its identity by shaping and overcoming non-identical moments, that is, dialectical identity. From this approach Hegel develops the Science of Logic considered, perhaps, as the last great system of Western metaphysics.

Contemporary Age

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels adopted an anti-metaphysical attitude based on their conception of dialectical materialism, which derives from Hegel's dialectical idealism. According to it, only matter is real, together with its changes. Dialectic explains these transformations, according to which all natural and social processes occur by contradiction. For example, in the analysis of the commodity in Capital, the commodity object is the "contradictory unit" of use value and exchange value. This explanation claims to be universal and valid for both nature and for society and thought. In his work Thesis on Feuerbach he concludes in the famous thesis 11: "Philosophers have only interpreted the world in different ways, but from what it is about transforming it". Although some aspects of Marxist thought can be interpreted as metaphysics, Marxism would criticize a certain way of doing metaphysics.

Friedrich Nietzsche considers Plato to be the initiator of metaphysical thought and makes him responsible for the split in being that will later have varied but constant forms. The division between the sensible world and the intelligible world, with its correlative body-soul, and the pre-eminence of the latter ensured by the theory of Ideas places the true world beyond the senses. This leaves out of thinking the becoming, that which cannot be grasped in the sensible-intelligible division due to its formless nature, and which is also allowed to escape by the subsequent Aristotelian divisions, such as substance-accident and act-potency.

Martin Heidegger said that our age is that of the «completion of metaphysics», since certain results have been produced since the beginnings of Western thought that configure a panorama that metaphysical thought can no longer account for. The very success of metaphysics has driven away from it. Given this, the power of thought consists precisely in knowing and intervening on the known. But metaphysical thought already lacks power since it has yielded its last fruits.

Heidegger stated that metaphysics is "Western thought in its totality of essence". The use of the term "essence" in this definition implies that the technique for studying metaphysics as a form of thought is or should be metaphysics in the first sense indicated above. This means that the critics of metaphysics as the essence of Western thought are aware that there is no "no man's land" in which to situate themselves, beyond that way of thinking; Only careful study and the conscious and rigorous modification of the tools provided by the philosophical tradition can adjust the power of thought to the transformations operated in what metaphysics studied: being, time, the world, man and his knowledge.. But this modification supposes, in turn, a "leap" that the entire tradition of thought has staged, pretended or dreamed of taking throughout its development. The leap out of metaphysics and therefore, perhaps the reversal of its consequences.

Heidegger characterized metaphysical discourse for its impotence to think about the ontic-ontological difference, that is, the difference between beings and being. Metaphysics refers to being the model of entities (things), but that would be irreducible to these: entities are, but the being of entities cannot be characterized simply as these. The being is thought of as a supreme entity, which identifies it with God; the ontotheological drive is a constant in Western thought. For Heidegger, metaphysics is the "forgetting of being", and the awareness of this forgetfulness should open a new era, faced with the possibility of expressing what has been left outside of thought.

Analytic philosophy was from its birth with authors such as Russell and Moore very skeptical regarding the possibility of a systematic metaphysics as it had been traditionally defended. This is due to the fact that the birth of analytical philosophy was mainly due to an attempted rebellion against the neo-Hegelian idealism then hegemonic in the British University. It would be from the twenties when the Vienna Circle would offer a total critique of metaphysics as a set of meaningless propositions for not meeting the verificationist criteria of meaning. However, this position is today a minority in the analytical panorama, where interest has been recovered in certain classical problems of metaphysics such as universals, the existence of God and others of an ontological type.

Post-structuralism (Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida) takes up Nietzsche's critique, and argues that what is unthinkable in metaphysics is precisely “difference” as such. The difference, in metaphysical thinking, is subordinated to the entities, between which it occurs as a "relation". The claim to "inscrib the difference in the concept" by transforming it and violating the limits of Western thought already appears as a claim that leads philosophy beyond metaphysics.

Contenido relacionado

Reason (disambiguation)

Golden ratio

Positivism