Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is the name by which the historical region of the Near East located between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers is known, although it extends to the fertile areas adjacent to the strip between both rivers, and which roughly coincides with the non-desert areas of present-day Iraq and the border zone of northern and eastern Syria.

The term refers mainly to this region in the Ancient Age that was divided into Assyria (to the north) and Babylonia (to the south). Babylonia (also known as Chaldea), in turn, was divided into Acadia (upper part) and Chaldea (lower part). Its rulers were called patesi.

The names of cities like Ur or Nippur, of legendary heroes like Gilgameš, of the Code of Hammurabi, of the amazing buildings known as ziggurats, come from Ancient Mesopotamia. And episodes mentioned in the Bible or in the Torah, such as the universal flood or the legend of the Tower of Babel, allude to events that occurred in this area.

The history of Mesopotamia is divided into five stages: the Sumerian period, the Akkadian Empire, the Babylonian Empire, the Assyrian Empire, and the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

The social system was linked to the economy, so there was no caste or stratification, only differentiation in economic positions.

The economy of Mesopotamia was based on agriculture and the division of land as follows:

- State or public sector: the property of the temple and the palace, as the property of the god, and aimed at the production for the maintenance of the temple and the staff (writers, priests and administrative) and were worked by peasants influenced by physical or ideological coercion, who were paid with barley rations, wool and oil for illumination and hygiene in quantities according to age and sex.

- Private sector: they were communal and private land, managed by macro families in exchange for tribute.

The following socio-economic distinctions could also be found within the population, which was subject to their level of economic dependence or independence:

- Mezquinos: it was certain sectors that could live only of their body work and the cultivation of their plots. They belong to the weakest social groups because they are socially unprotected and are subject to the king (responsible of the temple).

- Men: they are citizens with the possibility of accessing the land. They are linked to the palatial activity, plot owners, scribes or officials who have managed to accumulate the capital for the exploitation of the lands.

- Servants: These are people who had debts to the palace and were volunteer servants for payment.

- Slaves: captive enemy warriors.

Etymology

The regional place name Mesopotamia (/m ɛ s ə p ə teɪ mi ə/, Ancient Greek: Μεσοποταμια "[the land] between rivers"; Arabic: Balad ٱ lrafdyn Bilad 'ar-Rafidayn' or Arabic: International ٱ lnhryn 'AN-Nahrayn Bayn'; Persian: myanrvdan miyan Rudan; Syriac: quartet: /? 34;medium" and ποταμός (potamos) "river" and translates as "(land) between rivers". It is used throughout the Greek Septuagint (c. 250 BCE) to translate the Hebrew and Aramaic equivalent Naharaim. An earlier Greek use of the name Mesopotamia is evident in The Anabasis of Alexander, which was written in the late 2nd century AD. C., but refers specifically to sources from the time of Alexander the Great. In the Anabasis, Mesopotamia was used to designate the land east of the Euphrates, in northern Syria.

The Aramaic term biritum / birit narim corresponded to a similar geographical concept. Later the term Mesopotamia was applied more generally to all the lands between the Euphrates and the Tigris, thus incorporating not only parts of Syria, but also almost all of Iraq and southeastern Turkey. The neighboring steppes west of the Euphrates and the western part of the Zagros Mountains are also often included under the broader term Mesopotamia.

A further distinction is usually made between northern or upper Mesopotamia and southern or lower Mesopotamia. Upper Mesopotamia, also known as Jazira, is the area between the Euphrates and Tigris from their sources to Baghdad, while Lower Mesopotamia is the area from Baghdad to the Persian Gulf and includes Kuwait and parts from western Iran.

In modern scholarly usage, the term Mesopotamia often also has a chronological connotation. It was generally used to designate the area until the Muslim conquests, with names like Syria, Jazira, and Iraq describing the region after That date. It has been argued that these later euphemisms are Eurocentric terms attributed to the region in the midst of various Western invasions of the 19th century.

Geography

Mesopotamia encompasses the land between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, both of which have their headwaters in the Taurus Mountains. Both rivers are fed by numerous tributaries, and the entire river system drains a vast mountainous region. Land routes in Mesopotamia generally follow the Euphrates because the banks of the Tigris are often steep and difficult. The region's climate is semi-arid with a vast desert expanse in the north giving way to a 15,000-square-kilometre (5,800-square-mile) region of swamps, lagoons, marshes, and reed banks in the south. In the far south, the Euphrates and Tigris join and flow into the Persian Gulf.

The arid environment spanning from the northern rainfed agriculture areas to the south, where agricultural irrigation is essential to earn excess energy on energy invested (EROEI). This irrigation is aided by a high water table and melting ice from the high mountain peaks of the northern Zagros Mountains and the Armenian Highlands, the source of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers for which the region is named. The utility of irrigation depends on the ability to mobilize sufficient labor for the construction and maintenance of canals, and this, from the earliest period, has aided the development of urban settlements and centralized systems of political authority.

Agriculture throughout the region has been supplemented by nomadic herding, where tent-dwelling nomads herded sheep and goats (and later camels) from river pastures in the dry summer months onto grazing lands seasonal on the desert fringe in the wet winter season. The area generally lacks building stone, precious metals, and timber, so it has historically engaged in long-distance trade in agricultural products to obtain these items from outlying areas. In the salt marshes to the south of the area, a complex fishing culture has existed since prehistoric times which has added to the cultural mix.

There have been periodic interruptions in the cultural system for various reasons. From time to time the demand for labor has led to population increases that exceed the limits of ecological carrying capacity, and in the event of a period of climatic instability, central government may collapse and populations decline. Alternatively, military vulnerability to invasion by marginal hill tribes or nomadic pastoralists has led to periods of commercial collapse and abandonment of irrigation systems. Similarly, centripetal tendencies among city-states have meant that central authority over the entire region, when imposed, tends to be short-lived, and localism has fragmented power into smaller tribal or regional units. These trends have continued to the present day in Iraq.

History

In the interior of Mesopotamia, agriculture and livestock were imposed between 6000 and 5000 BC. C., assuming the full entry into the Neolithic. During this period, the new production techniques that had been developed in the early Neolithic area spread through the regions of later development, including interior Mesopotamia. This fact led to the development of cities, some of the first being Bouqras, Umm Dabaghiyah and Yarim and, later, Tell es-Sawwan and Choga Mami, which formed the so-called Umm Dabaghiyah culture. Later this was replaced by the Hassuna-Samarra cultures, between 5000 and 5600 BC. C., and by the Halaf culture between 5600 and 4000 B.C. C. (late Halaf).

About 3000 B.C. C., the writing appeared, at that time used only to keep the administrative accounts of the community. The first writings that have been found are engraved on clay (very common in that area) with drawings made up of lines (pictograms).

Urban civilization continued to advance during the El Obeid period (5000 BC–3700 BC) with advances in ceramic and irrigation techniques and the construction of the first urban temples.

After El Obeid, the Uruk Period took place, in which urban civilization settled definitively with enormous technical advances such as the wheel and calculation, made by annotations on clay tablets and that would evolve towards the first forms of writing.

Sumerians and Akkadians

The Sumerians

Sumeria was the first Mesopotamian civilization. After the year 3000 B.C. C. the Sumerians created in lower Mesopotamia a set of city-states: Uruk, Lagaš, Kiš, Uma, Ur, Eridu and Ea whose economy was based on irrigation. They were governed by an absolute king, who called himself the "vicar" of the god protector of the city. The Sumerians were the first to use writing (cuneiform) and also built large temples (ziggurats).

The Archaic Dynastic Period

The spread of the advances of the Uruk culture throughout the rest of southern Mesopotamia gave rise to the Sumerian culture. These techniques allowed the proliferation of cities through new territories and regions. These cities were soon characterized by the appearance of walls, which seems to indicate that wars between them were frequent. It also highlights the expansion of writing that jumped from its administrative and technical role to the first dedicatory inscriptions on enshrined statues in temples.

Despite the existence of the Sumerian royal lists, the history of this period is relatively unknown, since a large part of the reigns exposed in them have impossible dates. Actually these lists were made from the 17th century B.C. C., and its creation was probably due to the desire of the monarchs to trace their lineage back to epic times. Some of the kings are probably real but there is no historical record of many others and others whose existence is known do not appear in them.

The Akkadian Empire

The prosperity of the Sumerians attracted diverse nomadic peoples. From the Arabian peninsula, Semitic tribes (Arabs, Hebrews, and Syrians) constantly invaded the Mesopotamian region starting in 2500 BC. C., until they established their definitive domain.

Circa 3000 B.C. C. spread to the north, creating different groups such as the Amorites, which include Phoenicians, Israelites and Arameans. In Mesopotamia, the Semitic people that acquired the greatest relevance were the Akkadians.

Circa 2350 B.C. C., Sargon, a usurper of Akkadian origin, seized power in the city of Kiš. He founded a new capital, Agade, and conquered the rest of the Sumerian cities, defeating the hitherto dominant king of Umma, Lugalzagesi. This was the first great Empire in history and would be continued by Sargon's successors, who would have to face constant revolts. Among them stood out the grandson of the conqueror, Naram-Sin. This stage marked the beginning of the decline of the Sumerian culture and language in favor of the Akkadians.

The Empire fell apart around 2220 BC. C., due to the constant revolts and invasions of Gutis and Amorite nomads. After its fall, the entire region fell under the rule of this tribe, which prevailed over the city-states of the region, especially around the destroyed Agade. The Sumerian chronicles consistently describe them in a negative light, as "horde of barbarians" or "mountain dragons", but it is possible that the reality was not so negative; In some centers there was a real flourishing of the arts, like the city of Lagaš for example, especially during the government of patesi Gudea. In addition to artistic quality, materials from distant regions were used in Lagaš's works: cedar wood from Lebanon or diorite, gold and carnelian from the Indus Valley; which seems to indicate that trade should not have been particularly weighed down. The southern cities, further away from the center of Guti power, bought their freedom in exchange for large tributes; Uruk and Ur prospered during their 4th and 2nd dynasties.

Sumerian Renaissance

According to a commemorative tablet it was Utu-hegal, king of Uruk, who, around 2100 B.C. C., defeated and expelled the Guti rulers from the Sumerian lands. His success would not be of much benefit to him since shortly after he was defeated by Ur-Nammu, the king of Ur, who became the hegemonic city in the entire region during the period of the Third Dynasty of Ur (also usually called Ur). this period Sumerian Renaissance). The Empire that emerged as a result of this hegemony would be as extensive or more than that of Sargon, from whom he would take the idea of a unifying Empire, an influence that can even be seen in the naming of the monarchs, who, in imitation of the Akkadians, will call themselves &# 34;kings of Sumer and Acad".

Ur-Nammu will be succeeded by his son Shulgi, who fought against the eastern kingdom of Elam and the nomadic tribes of the Zagros. This was succeeded by his son Amar-Sin and this one, first his brother, Shu-Sin and then another Ibbi-Sin. In the reign of the latter, the attacks of the Amorites, coming from Arabia, became especially strong and in 2003 B.C. C. the last predominantly Sumerian Empire fell. From now on it will be the Akkadian culture that predominates and later Babylon will inherit the role of the great Sumerian empires.

Babylonians and Assyrians

With the fall of the hegemony of Ur there was not a repeat of a period of darkness like the one that had occurred with that of the Akkadian Empire. This stage will be marked by the progressive rise of Amorite dynasties in practically all the cities of the region.

For the first 50 years it seems that it was the city of Isin that tried unsuccessfully to assert itself in the region. Later, around 1930 a. C. it will be the monarchs of Larsa who launch to the conquest of the neighboring cities, attacking Elam and the cities of Diyala and conquering Ur, despite which they did not achieve complete dominance in the region, although they retained their hegemony until practically the rise of Hammurabi's Paleo-Babylonian Empire, except for a period between 1860 and 1803 BCE. C. in which neighboring Uruk managed to challenge his leadership.

In Elam, Akkadian influence grew stronger and the kingdom became increasingly involved in Mesopotamian politics. In northern Mesopotamia, the first strong states began to emerge, possibly reformed by the existing trade between the southern areas and Anatolia, highlighting mainly the new kingdom of Assyria, which would eventually expand to the Mediterranean under the reign of Šamši-Adad I.

The Paleo-Babylonian Empire

In 1792 B.C. C. Hammurabi comes to the throne of the hitherto unimportant city of Babylon, from which a policy of expansion will begin. In the first place, he freed himself from the tutelage of Ur to, in 1786, confront the neighboring king of Larsa, Rim-Sin I, seizing Isin and Uruk from him; With the help of Mari, in 1762 he defeated a coalition of cities on the banks of the Tigris, to, a year later, conquer the city of Larsa. After this he proclaimed himself king of Sumer and Acad , a title that had arisen in the time of Sargon of Acad, and that had been used by the monarchs who achieved control of the entire region of Mesopotamia. After a new confrontation with a new coalition of cities he conquered Mari, after which, in 1753, he completed his expansion with the annexation of Assyria and Ešnunna, north of Mesopotamia.

Over the centuries, the image of the monarch was mythologized, not only due to his conquests, but also to his activity in the construction and maintenance of irrigation canals, and the elaboration of law codes, such as the well-known code of Hammurabi.

Hammurabi died in 1750 B.C. C., being succeeded by his son Samsu-iluna, who had to face an attack by the nomadic Casitas. This situation would be repeated in 1708 a. C., during the reign of Abi-Eshuh. Indeed, since the conqueror's death, the problems with the Casitas had multiplied. This pressure was constant and in progress during the 17th century B.C. C., which was wearing down the Empire. It was an attack by the Hittite king, Mursili I, that delivered the coup de grace to Babylon, after which the region fell under the power of the Cassites.

Assyrians

Around 1250 B.C. C. the Assyrians settled in the north of Babylon, who took control of the entire country. Its most important cities were Assur and Nineveh, and among its most illustrious monarchs the following stood out: Assurnasirpal, Assurbanipal, Salmanasar III, Sargon II and Sennaquerib. Babylonians and Medes allied and entered Assyria from the Iranian plateau, and finally, in 612 B.C. C. took and burned Nineveh.

The Neo-Babylonians

Babylonia resurfaced with the Chaldeans, another Semitic tribe, when it was refounded by their king Nabopolassar in the late VII century. His son, Nebuchadnezzar II & # 34; the Great & # 34;, was his successor and is considered one of the most important Babylonian kings as his domains reached from Mesopotamia to Syria and the Mediterranean coast.

Persian invasion

In the year 539 B.C. C., the Persian king Cyrus, the new king of Asia, occupied Babylon and established his power throughout Mesopotamia.

Archaeological history

The first surveys in the region were carried out in 1786 by the vicar general of Baghdad, Joseph de Beauchamps, but it would be necessary to wait until 1842 for the first real archaeological excavation, promoted by the French consul in Mosul, Paul Émile Botta, which it focused on the area of tell Kujunjik, near Nineveh. The results were not interesting but, after moving the excavation on the advice of a villager, some Assyrian bas-reliefs appeared, which were the first historical finds of the Mesopotamian civilizations, of which, until then, they had only been known from mentions in the Bible.

From this moment on, the investigation was marked by the rivalry between the English and the French. The first, led by Austen Henry Layard, discovered Ashurbanipal's extremely important library; the second, the palace of Sargon II in Khorsabad, whose findings had an unfortunate end when a boat with 235 boxes of material sank in the Tigris.

In the southern area, in the 1850s, the cities of Uruk, Susa, Ur and Larsa were discovered, although it was not after 1875 when evidence of the Sumerian civilization was found. Up until the early years of the XX century, a large number of remains appeared, including a large number of statues of Gudea. German and American excavations also begin to progress at this stage.

One of the main characteristics of the archaeological sites in the area is that texts written in cuneiform have been found in great abundance, mainly on raw clay tablets, which have withstood the passage of time, which has made it possible to preserve some of the first pages of human history.

Culture

The culture of Mesopotamia was a pioneer in many of the branches of knowledge: they developed the writing that was called cuneiform, at first pictographic, and later phonetics; in the field of law, they created the first law codes; In architecture, they developed important advances such as the vault and the dome, created a calendar of 12 months and 365 days, and invented the sexagesimal numbering system.

Science

Many of them ventured into what today we call science or mathematics, also bequeathing important concepts such as the atomic theory (Democritus), various mathematical theorems (Thales of Miletus, Pythagoras, etc.), medicine (Hippocrates), the theory of the four humors (Empedocles), etc.

Math

Mesopotamian mathematics and science were based on a sexagesimal numbering system (base 60). This is the source of the 60-minute hour, the 24-hour day, and the 360-degree circle. The Sumerian calendar was based on the seven-day week. This form of mathematics was instrumental in the early creation of maps. The Babylonians also had theorems on how to measure the area of various shapes and solids. They measured the circumference of a circle as three times the diameter and the area as one twelfth of the square of the circumference, which would be correct if π were set to 3. The volume of a cylinder was taken to be the product of the area of the base and the height. The frustum of a cone or a square pyramid was incorrectly taken to be the product of the height and half the sum of the bases. Also, there was a recent discovery where a tablet used π as 25/8 (3.125 instead of 3.14159 ~). The Babylonians are also known by the Babylonian mile, which was a measure of distance equal to about seven modern miles (11 km). This measure of distances eventually became a mile of time used to measure the travel of the Sun, thus representing time.

Astronomy

Since Sumerian times, temple priests had tried to associate current events with certain positions of the planets and stars. This continued until Assyrian times, when the Limmu lists were created as an association of year-by-year events with planetary positions, which, when they have survived to the present day, allow precise associations of relative relationship with absolute dating to establish Mesopotamian history..

Babylonian astronomers were very adept at mathematics and could predict eclipses and solstices. Scholars thought that everything had a purpose in astronomy. Most of these related to religion and omens. Mesopotamian astronomers developed a 12-month calendar based on the cycles of the moon. They divided the year into two seasons: summer and winter. The origins of astronomy and astrology date from this time.

During the 8th century and the VII a. C., Babylonian astronomers developed a new approach to astronomy. They began to study philosophy on the ideal nature of the early universe and began to employ an internal logic within their predictive planetary systems. This was a major contribution to astronomy and the philosophy of science and some scholars have referred to this new approach as the first scientific revolution. This new approach to astronomy was adopted and developed in Greek and Hellenistic astronomy.

In Seleucid and Parthian times, astronomical reports were thoroughly scientific; how soon their advanced knowledge and methods were developed is uncertain. The Babylonian development of methods for predicting the motions of the planets is considered an important episode in the history of astronomy.

The only known Greco-Babylonian astronomer who supported a heliocentric model of planetary motion was Seleucus of Seleucia (b. 190 BC). Seleucus is known for the writings of Plutarch. He supported Aristarchus of Samos's heliocentric theory where the Earth revolved around its own axis which in turn revolved around the Sun. According to Plutarch, Seleucus even proved the heliocentric system, but it is not known what arguments he used (except that he theorized correctly about the tides as a result of lunar attraction).

Babylonian astronomy served as the basis for much of Greek, classical Indian, Sasanian, Byzantine, Syrian, medieval Islamic, Central Asian, and Western European astronomy.

Medicine

The oldest Babylonian texts on medicine date back to the Old Babylonian period in the first half of the 2nd millennium BC. However, the most extensive Babylonian medical text is the Diagnostic Manual written by the ummânū, or chief scholar, Esagil-kin-apli of Borsippa, during the reign of the king Babylonian Adad-apla-iddina (1069-1046 BCE)

Along with contemporary Egyptian medicine, the Babylonians introduced the concepts of diagnosis, prognosis, physical examination, enemas, and prescriptions. In addition, the Diagnostic Manual introduced the methods of therapy and etiology and the use of empiricism, logic and rationality in diagnosis, prognosis and therapy. The text contains a list of medical symptoms and often detailed empirical observations along with the logical rules used to combine the symptoms observed in a patient's body with the patient's diagnosis and prognosis.

A patient's symptoms and illnesses were treated through therapeutic means such as bandages, creams, and pills. If a patient could not be physically cured, Babylonian doctors often relied on exorcism to cleanse the patient of any curses. The Esagil-kin-apli Manual of Diagnosis was based on a logical set of axioms and assumptions, including the modern view that through examination and inspection of symptoms of a patient, it is possible to determine the patient's disease, its etiology, its future development, and the patient's chances of recovery.

Esagil-kin-apli discovered a variety of diseases and described their symptoms in his Diagnostic Manual. These include the symptoms of many varieties of epilepsy and related diseases, along with the diagnosis and prognosis of it.

Literature

Before the development of literature, written language was used to keep administrative accounts in the community. Over time, it began to be used for other purposes, such as explaining facts, quotes, legends or catastrophes.

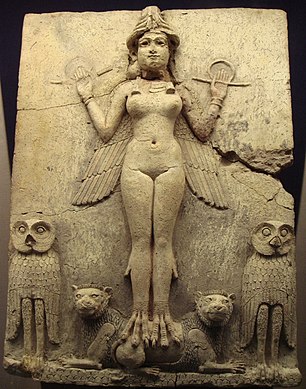

Sumerian literature comprises three major themes: myths, hymns, and lamentations. The myths are made up of brief stories that try to outline the personality of the Mesopotamian gods: Enlil, the main god and progenitor of the minor divinities; Inanna, goddess of love and war; or Enki, god of fresh water, frequently faced with Ninhursag, goddess of the mountains. Hymns are texts in praise of gods, kings, cities or temples. Lamentations relate catastrophic themes such as the destruction of cities or palaces and the resulting abandonment of the gods.

Some of these stories may have been supported by historical events such as wars, floods, or the building activity of an important king, magnified and distorted over time.

A creation typical of Sumerian literature was a type of dialogue poems based on the opposition of contrary concepts. Proverbs are also an important part of Sumerian texts.

Religion

The religion was polytheistic; in each city different gods were worshiped, although there were some common ones. These include:

- Anu: God of heaven and father of the gods.

- Enki: god of wisdom. I had the mission to create the man.

- Nannar: god of the moon.

- Utu: God of the Sun (about 5100 B.C. was called Ninurta).

- Inanna: goddess of love and war; later associated with the goddess Venus.

- Enlil: god of agriculture.

In the 17th century B.C. C., King Hammurabi unified the State, made Babylon the capital of the empire and imposed Marduk as the main god. This god was in charge of reestablishing the celestial order, of making the earth emerge from the sea and of sculpting the body of the first man before dividing up the domains of the universe among the other gods.

Something that characterized these gods was that they were associated with different activities; that is to say, there were gods of livestock, writing, clothing, etc., which led to a very broad pantheon

See: Deities by attributes.

Philosophy

The many civilizations in the area influenced the Abrahamic religions, especially the Hebrew Bible. His cultural values and literary influence are especially evident in the Book of Genesis.

Giorgio Buccellati believes that the origins of philosophy go back to early Mesopotamian wisdom, which embodied certain philosophies of life, particularly ethics, in the form of dialectics, dialogues, epic poetry, folklore, hymns, lyrics, works in prose and proverbs Babylonian reason and rationality developed beyond empirical observation.

The earliest form of logic was developed by the Babylonians, especially in the rigorous non-ergodic nature of their social systems. Babylonian thought was axiomatic and is comparable to "ordinary logic" Described by John Maynard Keynes. Babylonian thought was also based on an open systems ontology that is compatible with the ergodic axioms. Logic was employed to some extent in Babylonian astronomy and medicine.

Babylonian thought had a considerable influence on early Greek and Hellenistic philosophy. In particular, the Babylonian text Dialogue of Pessimism contains similarities to the agonistic thought of the sophists, the Heraclitean doctrine of dialectic, and Plato's dialogues, as well as a precursor of the Socratic method. The Ionian philosopher Thales was influenced by Babylonian cosmological ideas.

Languages

The early development of agriculture in the region may have allowed numerous small human groups to spread independently throughout the region, causing the region's linguistic diversity to be initially very large. This situation contrasts with that which occurs when agricultural human groups with superior technology penetrate a territory less densely populated by semi-nomadic populations, which gives rise to a much lower diversity, as happened in Europe with the entry of the Indo-European peoples.

In Mesopotamia two large linguistic families are recognized: the Indo-European (whose presence is due to several waves, so there are languages from different branches) and the Semitic (of which two branches are attested). Along with these there is a significant number of isolated languages (Sumerian, Elamite) or quasi-isolates (Hurrian-Uratian), and a number of poorly documented languages whose affiliation cannot be adequately specified (Casita, Hatti, Kaskas). Many of the isolates, quasi-isolates and unclassified seem to have ergative features, which typologically brings them closer to some Caucasian languages, although this is not proof of kinship, as these features could be a sign that an area may have existed in the past. linguistics.

Festivals

The ancient Mesopotamians had ceremonies every month. The theme of each month's rituals and festivals was determined by at least six important factors:

- The lunar phase (a growing moon meant abundance and growth, while a waning moon was associated with the decline, conservation and festivals of the underworld)

- The annual agricultural cycle phase

- Equinoxes and solstices

- The local myth and its divine patterns

- The success of the reigning monarch

- The Akitu, or New Year's Festival (first full moon after spring equinox)

- Commemoration of specific historical events (foundation, military victories, temple festivals, etc.)

Music

Main article: Music of Mesopotamia

Some songs were written for the gods, but many were written to describe important events. Although music and songs amused kings, they were also enjoyed by common people who liked to sing and dance in their homes or in the markets. Songs were sung to the children who passed them on to their children. Thus the songs were passed down through many generations as an oral tradition until writing became more universal. These songs provided a means of transmitting through the centuries very important information about historical events.

The Oud (Arabic: العود) is a small stringed musical instrument used by the Mesopotamians. The oldest pictorial record of the Oud dates back to the Uruk period in southern Mesopotamia over 5,000 years ago. It is on a cylinder seal currently housed in the British Museum and purchased by Dr. Dominique Collon. The image shows a woman crouched with her instruments in a boat, playing with her right hand. This instrument appears hundreds of times throughout Mesopotamian history and again in ancient Egypt beginning in the 18th Dynasty in long-necked and short-necked varieties. The oud is considered as a precursor of the European ones. lute. Its name is derived from the Arabic word العود al-'ūd 'the wood', which is probably the name of the tree from which the oud was made. (The Arabic noun, with the definite article, is the source of the word 'lute'.)

Games

Hunting was popular among Assyrian kings. Boxing and wrestling appear frequently in art, and some form of polo was probably popular, with men sitting on other men's shoulders rather than on horses. They also played majore, a game similar to sports rugby, but with a wooden ball. They also played a board game similar to senet and backgammon, now known as the 'Royal Game of Ur'.

Family Life

Mesopotamia, as evidenced by successive legal codes, those of Urukagina, Lipit Ishtar and Hammurabi, throughout its history became more and more of a patriarchal society, in which men were much more powerful than women. For example, during the early Sumerian period, the "en", or high priest of male gods was originally female, that of female goddesses, male. Thorkild Jacobsen, as well as many others, has suggested that early Mesopotamian society was governed by a "council of elders" in which men and women were equally represented, but that over time, as the status of women declined, that of men rose. As for schooling, only royal sons and the sons of the wealthy and professionals, such as scribes, doctors, and temple administrators, attended school. Most of the boys were taught their father's trade or learned a different one, while the girls had to stay at home with their mothers to learn cleaning, cooking and taking care of the younger children. Some children would help crush grain or clean birds. Unusually for that historical period, Mesopotamian women had rights. They could own property and, if they had a good reason, get divorced.

Burials

Hundreds of tombs have been excavated in different parts of Mesopotamia, revealing information about Mesopotamian burial habits. In the city of Ur, most of the people were buried in family tombs under their houses, along with some possessions. Some have been found wrapped in mats and rugs. The deceased children were put in large "jars" They were placed in the family chapel. Other remains have been found buried in common cemeteries in the city. 17 tombs have been found with very precious objects in them. It is assumed that these were royal tombs. Rich from various periods, they have been found to have sought burial in Bahrain, identified with Sumerian Dumemun.

Art

In the fertile zone of both plains, abundantly irrigated in its lower part by the two rivers that delimit this civilization, the nomadic peoples who crossed it soon became sedentary, becoming farmers and developing a culture and an art with an astonishing variety of forms and styles.

All in all, art in general maintains enough unity in terms of its intentionality, which results in a somewhat rigid, geometric and closed art, since, above all, it has a practical and not an aesthetic purpose and is developed at the service of society.

Sculpture

Sculpture represents both gods and sovereigns or officials, but always as individualized persons (sometimes with their name engraved), and seeks to replace the person rather than represent it. The head and face were disproportionate with respect to the body, which is why it is said that they developed the so-called conceptual realism: they simplified and regularized natural forms through the law of frontality (absolutely symmetrical right and left parts) and geometrism (figure within a geometric scheme that used to be the cylinder or the cone). Human representations showed a total indifference to reality, although animals showed greater realism.

Some recurring themes of Mesopotamian sculpture are monumental bulls, highly stylized and realistic (protective, monstrous and fantastic genies like everything supernatural in Mesopotamia). His main techniques were monumental relief, stele, parietal relief, glazed brick relief, and stamp: other ways to sculpt and develop authentic comics or narratives on them.

Painting

Due to the characteristics of the country, there are very few samples of painting; however, the art is very similar to the art of the Magdalenian period of prehistory. The technique was the same as in the parietal relief, without perspective. Like the mosaics (more enduring and characteristic) it had a more decorative purpose than the other facets of art.

In painting and engraving, the hierarchy was shown according to the size of the people represented in the work: those with the highest rank were shown larger compared to the rest.

The painting was strictly decorative, as it was used to embellish the architecture. It lacks perspective, and it is chromatically poor: only white, blue and red prevail. The tempera technique was used, which can be seen in the decorative mosaics or tiles. The paint was used in domestic decoration. The subjects were scenes of wars and ritual sacrifices with a lot of realism, and geometric figures, people, animals and monsters were represented, without representing shadows.

Architecture

The Mesopotamians had a very particular architecture due to the resources available. They made use of the two basic construction systems: the vaulted and the lintelled.

They built mosaics painted in bright colors, such as black, green or bicolor, as murals. The buildings had no windows and light was obtained from the roof. They were concerned with earthly life and not with that of the dead, therefore the most representative buildings were the temple and the palace.

The temple was the religious, economic and political center. It had farmland and herds, warehouses (where the crops were kept) and workshops (where utensils, copper and ceramic statues were made). The priests organized trade and employed peasants, herders, and artisans, who were paid plots of land to grow grain, dates, or wool. In addition, the ziggurats had a large patio with rooms to house the people who lived in this town.

Regulated urbanism was present in some cities, such as the Babylon of Nebuchadnezzar III, mostly with a checkerboard design. As for the engineering works, the very extensive and ancient network of canals that linked the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and their tributaries stands out, favoring agriculture and navigation.

Technology

The development of technology in Mesopotamia was conditioned in many aspects to advances in the domain of fire, achieved by improving the thermal capacity of the ovens, with which it was possible to obtain plaster (from 300 ° C), and lime (from 800 °C). With these materials, wooden containers could be covered, which allowed them to be placed on direct fire, a predecessor technique of ceramics that has been called "white tableware".

The beginnings of this technique have been found in Beidha, south of Canaan, and date back to the 9th millennium BC. C. approximately; from the subsequent millennia it spreads northwards and to the rest of the Near East, covering it completely between 5600 and 3600 BC. C.

Ceramics

In Mesopotamia, ceramics began to be developed at the beginning of the Neolithic, which is why we speak of a Pre-Pottery Neolithic. After this, there is a period in which ceramics appear intermittently in the remains. This is due, more than to a series of discoveries and forgetfulness, to the fact that the "white crockery" it was still sufficient for most applications. Around the fourth millennium B.C. C. ceramics reached full development, with kilns where the fire and the firing chamber were well differentiated.

From here, and with the control of even higher temperatures, a new technique arose: vitrification of the paste. Around the 3rd millennium B.C. C., during the Jemdet Nasr period, it was possible to manufacture glass pearls and a millennium later the technique of glazing was already mastered. Finally, during the second millennium B.C. C., the manufacture of glass objects was achieved.

Metallurgy

The use of small carved metal objects had been a constant in the region since the 6th millennium BC. C., however it was not until the development of more powerful furnaces when the use of these materials became general through the appearance of metallurgy. This change can be placed in the middle of the III millennium BC. c.; a greater quantity of metallic objects begins to be found; Due to their composition, it can be seen that these objects are obtained by casting, not by carving metals in their natural state, and they began to experiment with alloys.

With the development of alloys came the birth of bronze metallurgy, which was differentiated into two aspects depending on the metals with which the alloy was obtained, whether they were copper and tin or copper and arsenic. Arsenous bronze developed in the areas of the Caucasus, eastern Anatolia, southern Mesopotamia, and the Mediterranean Levant, tracing a north-south axis. Tin bronze predominates in Iran, all of Mesopotamia, northern Syria, and Cilicia, tracing an east-west axis. The crossing point of these two axes is southern Mesopotamia, that is, the cradle of the Sumerian civilization. This situation is maintained during the 4th and 3rd millennia B.C. C., until in the second the arsenous bronze disappears.

Between 1200 and 1000 B.C. C. a new advance is produced: iron, which until then had been scarce to the point of costing the same as gold, is popularized probably due to the discovery of new techniques, achieved in the area of northern Syria or in the land of the Hittites.

Government

The geography of Mesopotamia had a profound impact on the political development of the region. Between the rivers and streams, the Sumerian people built the first cities along with irrigation canals that were separated by vast expanses of open desert or swamp where nomadic tribes roamed. Communication between the isolated cities was difficult and sometimes dangerous. Thus, each Sumerian city became a city-state, independent from the others and protector of its independence. Sometimes a city would try to conquer and unify the region, but such efforts were resisted and failed for centuries. As a result, Sumer's political history is one of almost constant warfare. Eventually Sumer was unified by Eannatum, but the unification was tenuous and did not last as the Akkadians conquered Sumer in 2331 BC. C. only a generation later. The Akkadian Empire was the first successful empire that lasted for more than a generation and saw the peaceful succession of kings. The empire was relatively short-lived, as the Babylonians conquered them in a few generations.

Kings

Main articles: Sumerian king list and Babylonian king list

The Mesopotamians believed their kings and queens descended from the City of Gods, but unlike the ancient Egyptians, they never believed their kings were actual gods. Most kings called themselves "king of the universe" or "great king". Another common name was " shepherd ", since kings had to take care of their people.

Power

When Assyria became an empire, it was divided into smaller parts, called provinces. Each of these is named after its major cities, such as Nineveh, Samaria, Damascus, and Arpad. They all had their own governor who had to make sure everyone paid their taxes. Governors also had to summon soldiers for war and supply workers when a temple was built. He was also responsible for enforcing the laws. In this way, it was easier to maintain control of a large empire. Although Babylon was a fairly small state in Sumerian times, it grew enormously during Hammurabi's rule. He was known as 'the lawgiver,' and soon Babylon became one of the major cities of Mesopotamia. It was later called Babylon, which meant 'the gateway of the gods'. It also became one of the largest centers of learning in history.

War

With the end of the Uruk phase, walled cities grew and many isolated Ubaid villages were abandoned, indicating an increase in communal violence. One of the early kings of Lugalbanda was supposed to have built the white walls around the city. As the city-states began to grow, their spheres of influence overlapped, creating arguments among other city-states, especially over land and canals. These arguments were recorded on tablets several hundred years before any major war: the first recording of a war occurred around 3200 BC. C., but it was not common until about 2500 a. An early dynastic king II (Ensi) of Uruk in Sumer, Gilgamesh (c. 2600 BCE), was praised for military exploits against Humbaba, guardian of the Cedar Mountain, and was later celebrated in many poems and later songs in which it was stated that he was a two-thirds god and only one-third human. The Post-Late Early Dynastic III (2600–2350 BC) Vulture Stela, commemorating the victory of Eannatum of Lagash over the neighboring rival city of Umma, is the world's oldest monument celebrating a massacre. From this moment on, warfare was incorporated into the Mesopotamian political system. Sometimes a neutral city can act as an arbitrator for the two rival cities. This helped form unions between cities, leading to regional states. When empires were created, they went to war more with foreign countries. King Sargon, for example, conquered all the cities in Sumer, some cities in Mari, and then went to war with northern Syria. Many Assyrian and Babylonian palace walls were decorated with the images of successful fights and the enemy desperately escaping or hiding in the reeds.

Laws

The Mesopotamian city-states created the first legal codes, drawn from legal precedence and decisions made by kings. The codes of Urukagina and Lipit Ishtar have been found. The most famous of these was that of Hammurabi (created around 1780 BC), due to its set of laws, being one of the earliest sets of laws found and one of the best preserved examples of this type of document from ancient times. Mesopotamia. He codified more than 200 laws for Mesopotamia. Examination of the laws shows a progressive weakening of women's rights and an increasing severity in the treatment of slaves.

Technological advances

Some of the creations that we owe to the civilizations that inhabited Mesopotamia are:

- Writing (quaneiform writing).

- The coin.

- The wheel.

- The first notions of astrology and astronomy.

- The development of the sexagesimal system and the first code of laws, written by King Hammurabi.

- The postal or mail system.

- Artificial irrigation.

- The plow.

- The boat and the candle.

- I snare them for animals.

- The metallurgy of copper and bronze.

- A calendar of 12 months and 360 days.

Contenido relacionado

Roman Republic (1798-1799)

Independence of Chile

Albanian coat of arms