Mayan languages

The Mayan languages —also called simply Maya— are a language family spoken in Mesoamerica, mainly in Belize, Guatemala, and southeastern Mexico.

The Mayan languages derive from Proto-Maya, a protolanguage that may have been spoken around 5,000 years ago judging by the degree of internal diversification in a region close to where Mayan languages are currently spoken. These languages are also part of the Mesoamerican linguistic area, an area of linguistic convergence developed through millennia of interaction between the peoples of Mesoamerica.

This whole family shows the basic characteristics of this linguistic area, such as the use of related nouns instead of prepositions to indicate spatial relationships. They also have grammatical and typological features that differentiate them from other Mesoamerican languages, such as the use of ergativity in the grammatical treatment of verbs, subjects, and objects, specific inflectional categories in verbs, and their own grammatical category. The oldest historically attested Mayan language is Classic Mayan.

In pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, some languages in the family were written using glyphs. Its use was very extensive, particularly during the classic period of the Mayan culture (c. 250-900 AD). The collection of more than 10,000 known Maya inscriptions on buildings, monuments, pottery, and bark paper codices, combined with the rich colonial Maya literature (16th centuries, xvii and xviii) written in the Latin alphabet, are important for the understanding of pre-Columbian history.

The Mayense family is one of the best documented and possibly the most studied in the Americas. In 1996, Guatemala officially recognized 21 Mayense languages and on May 26, 2003, added the Chalchiteko language, bringing the total to 22 now languages in official recognition; while Mexico made eight more languages official through the General Law of Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2001.

History

The Mayan languages are derived from Proto-Maya (sometimes called Nab'ee Maya' Tzij "the ancient Mayan language"). it may have been spoken in the Cuchumatanes mountains of central Guatemala, in an area that roughly corresponds to what Kanjobalan currently occupies.

The first division occurred around 2200 B.C. C. when the Huastecan group began to differentiate itself from the common Maya, after the Huastecan speakers migrated northeast along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. Proto-Yucatec and Proto-Cholano speakers later broke away from the main group and migrated north to the Yucatán Peninsula around 1600 BCE. C.

Speakers of the Western Branch moved south into the region now inhabited by the Mamean and Quichean people. When the proto-Tzeltalan speakers later separated from the Cholano group and moved south to the Chiapas highlands, they came into contact with the speakers of the Mixe-Zoquean languages.

In the Archaic period (before 2000 BC) there must have been contacts with speakers of the Mixe-Zoquean languages, which would explain the considerable number of loanwords from the Mixe-Zoquean languages in many Mayan languages. This led scholars to hypothesize that the ancient Maya were dominated by speakers of the Mixe-Zoquean languages, possibly from the Olmec culture.

In the case of the Xinca and Lenca languages, on the other hand, the Mayan languages are more often the dominant, rather than the recipient of loanwords. This suggests a period of Mayan domination over the Lenca and Xinca ethnic groups.

The split between the proto-Yucatecan of the Yucatán peninsula and the proto-Cholano of the Chiapas Highlands and El Petén had already occurred before the Classic period, at the time most Maya epigraphic inscriptions were made. In fact, the two variants of Mayense are attested in glyphic inscriptions from Mayan sites of the time, and both are commonly referred to as a "classic Mayan language" (even when they corresponded to different languages).

During the classical period the main branches diversified further into the different languages recognizable today. However, glyphic texts only record two variants of Maya: a Cholan variety found in texts written in the southern Maya area and the Highlands, and a Yucatecan variety found in texts from the Yucatán Peninsula.

Recently, it has been suggested that the specific variety of Cholano found in the glyphic texts is known as "Classical Choltian", the ancestral language of modern Chorti and Choltí. It is thought that the origin of this language may be in the west or south-central Petén; and would have been used in inscriptions and even spoken by elites and priests. The fact that only two linguistic variants are found in the glyphic texts is most likely because they have served as prestigious dialects in all parts of the world. from the Mayan region; the glyphic texts would have been composed in the language of the elite. However, different Maya groups would have spoken several different languages during the Classic period.

During the Spanish colonization of Mesoamerica, all indigenous languages were displaced by Spanish, which became the new language of prestige. The Mayan languages were no exception, and their use in many important domains of society, including administration, religion, and literature, ended. The Maya region was more resistant to outside influence than others, and perhaps for this reason many Maya communities still retain a high proportion of bilingual and monolingual speakers. However, Spanish now dominates the entire Maya region.

Some Mayan languages are moribund or threatened, although they remain widely used and sociolinguistically viable. The latter continue to be the mother tongue of many people and have speakers of all age groups, and are also used in almost all social spheres.

During the 20th century d. BCE, archaeological discoveries fostered nationalistic and ethnic pride, which led Maya-speaking peoples to begin to develop a shared ethnic identity as Maya and the inheritors of the great Mayan culture.

The broader meaning of «Maya», in addition to geographical aspects, is characterized by linguistic factors, but also refers to ethnic and cultural traits. Most Maya identify themselves primarily with one particular ethnic group, e.g. eg "yucateco" or "quiché"; but they also acknowledge a shared Maya kinship.

Language has been instrumental in defining the limits of this kinship. Paradoxical perhaps, this pride of unity has led to an insistence on the separation of various Mayan languages, some of which are so closely related that they could easily be referred to as dialects of a single language. However, since the term "dialect" has been used by some with racial overtones in the past, making a false distinction between Amerindian "dialects" and European "languages", the preferential use in recent years has been to denote the linguistic varieties spoken by a diverse ethnic group as separate languages.

In Guatemala, matters such as the development of standardized orthographies for the Mayan languages are governed by the Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala (ALMG) which was founded by Mayan organizations in 1986. Following the 1996 peace accords it has been gaining increasing recognition as the regulatory authority on Mayan languages among Mayan scholars and the Mayan people themselves.

Genealogy and classification

Relations with other families

The Mayan language family has no proven genetic relationship to other families. The similarities with some Mesoamerican languages are understood to be due to the diffusion of linguistic features from neighboring languages into Maya and not to common ancestry. Mesoamerica has proven to be an area of substantial linguistic diffusion.

According to Lyle Campbell, an expert in Mayan languages, the most promising proposal is the Macro-Maya hypothesis, which postulates a distant linguistic relationship between this family, the Mixe-Zoquean and Totonacan languages, but more evidence is lacking to support or refute this hypothesis.

Historically, other kinship hypotheses have been proposed, which tried to relate the Mayan family to other linguistic families and isolated languages, but in general these have not been supported by most specialists. Examples include the relationship of the Maya to the Uru-Chipaya, Mapudungun, Lenca, Purépecha, and Huave. Typologically it has similarities with the Xinca but there seems to be no genetic relationship, being rather the result of linguistic borrowings and cultural influence. Maya has also been included, in other hypotheses, within the Penuti languages. Linguist Joseph Greenberg includes Maya in his highly controversial Amerindian hypothesis, which is rejected by most historical linguists.

Internal classification and subdivisions

The Mayan family is well documented and its internal genealogical classification scheme is widely accepted and established; however, a point still in dispute is the position of the Cholano and the Kanjobalan-Chujean. Some scholars think these form a separate western branch (as in the lower diagram). Other linguists do not support the postulate of a particularly close relationship between Cholan and Kanjobalan-Chujean, so they classify these as two distinct branches that derive directly from the Mayan proto-language.

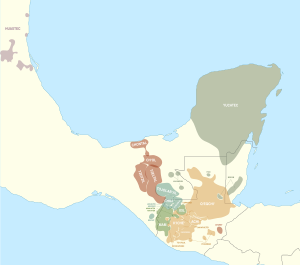

Geography and demographics

List of Mayan Languages (Ethnologue, 2021)

Huastecan Branch

Huastec is spoken in the Mexican states of Veracruz and San Luis Potosí by around 110,000 people. It is the most divergent of the other modern Mayan languages. Chicomuceltec was a language related to Huastec and spoken in Chiapas that probably became extinct before 1982. A branch that separated from the Proto-Maya formed by Huastec and Chicomucelco, its separation occurred when Mixezoquez speakers entered the Gulf of Mexico, separating the Huastec from the rest.

Yucatan Branch

Yucatec Mayan (known simply as Maya by its speakers) is the most widely spoken Mayan language in Mexico. It is currently spoken by approximately 800,000 people, the vast majority of speakers living in the Yucatán Peninsula. It has a rich post-colonial literature and remains common as a mother tongue in rural areas of Yucatán and the adjacent states of Quintana Roo and Campeche.

The other three Yucatecan languages are Mopan, spoken by about 10,000 people mainly in Belize; Itza, a dying or perhaps extinct language, native to or from the Petén of Guatemala; and Lacandon, also in danger of extinction with about 1,000 speakers in some villages near the Lacandon jungle in Chiapas.

The Cabil language was a Mayan language, now extinct, spoken in the towns of Chicomuselo, Comalapa, Yayagüita and Huitatán, in the state of Chiapas.

Western Branch

Cholano

In the past, the Cholan languages occupied an important part of the Mayan area; although today the language with the most speakers is Ch'ol spoken by some 130,000 people in Chiapas. Its closest relative, the Chontal language of Tabasco, is spoken by 55,000 individuals in the state of Tabasco. Another related language, now at risk of extinction, is Chorti, which is spoken by 30,000 people in Guatemala. It was also previously spoken in far western Honduras and El Salvador but the El Salvador variant is now extinct and the from Honduras is considered moribund. Choltí, a sister language to Chorti, is also extinct. All these languages would be descendants of the main language used in Mayan epigraphy, that is, the Classic Mayan language.

The Cholan languages are believed to be the most preserved in vocabulary and phonology, and are closely related to Classic period inscriptions found in the central lowlands. They may have served as prestige languages, coexisting with other dialects in some areas. This assumption provides a plausible explanation for the geographic distance between the Chorti zone and the areas where Chol and Chontal are spoken.

Tzeltalan

The closest relatives of the Cholan languages are the Tzeltalan branch languages, Tzotzil and Tzeltal, both of which are spoken in Chiapas by large and stable or growing populations (265,000 for Tzotzil and 215,000 for Tzeltal). Tzotzil and Tzeltal have a large number of monolingual speakers.

Kanjobalan

Kanjobal is spoken by 77,700 people in the Huehuetenango department of Guatemala, with small populations elsewhere. Jacalteco (also known as Poptí) is spoken by about 100,000 in various municipalities of Huehuetenango. Another member of this branch is Acateco, with more than 50,000 speakers in San Miguel Acatán and San Rafael La Independencia.

Chuj is spoken by 40,000 people in Huehuetenango, and by 9,500 people, mostly refugees, near the border in Mexico, in the municipality of La Trinitaria, Chiapas, and the villages of Tziscao and Cuauhtémoc; Tojolabal is spoken in eastern Chiapas by 36,000 people.

Eastern Branch

Quiché-Mameano

The group of Quiché-Mam languages spoken in the Guatemalan mountains is divided into two sub-branches and three sub-families:

Kekchí, which constitutes by itself one of the sub-branches within Quiché-mam. This language is spoken by about 400,000 people living in the southern Guatemalan departments of Petén and Alta Verapaz, and also in Belize by 9,000 more speakers. In El Salvador it is spoken by 12,000 people as a result of recent migrations.

The Uspantec language, also a direct descendant of Proto-Quiché-Mam, is native only in the Uspantán municipality in the El Quiché department, and has about 30,000 speakers.

Mameano

The largest language of this branch is Mam, spoken by 150,000 people in the departments of San Marcos and the Altos Cuchumatanes. Avocado is the language of 20,000 inhabitants of central Aguacatán, another municipality of Huehuetenango. Ixil is spoken by 69,000 in the "Triángulo Ixil" region of the department of El Quiché. Tectiteco (or Teco) is spoken by about 1,000 people in the municipality of Tectitán, and 1,000 refugees in Mexico. According to Ethnologue the number of Tectitecan speakers is growing.

Quichean

Quiché, the Mayan language with the largest number of speakers, is spoken by more than 2,000,000 people in the Guatemalan highlands, around the cities of Chichicastenango, Quetzaltenango, and the mountains of Cuchumatán, as well as by urban migrants in Guatemala City. The famous Mayan mythological document, the Popol Vuh, is written in Old-fashioned Quiché often called Classical Quiché. Quiché culture was at its pinnacle at the time of the Spanish conquest. Utatlán, near the present-day city of Santa Cruz del Quiché, was its economic and ceremonial center. Among its native speakers is the Nobel Peace Prize winner, Rigoberta Menchú.

Achí is spoken by 85,000 people in Rabinal San Miguel Chicaj, Cubulco and Salama, municipalities of Baja Verapaz. In some classifications, e.g. eg the one made by Campbell, the achí is counted as a form of the quiché. However, due to a historical division between the two ethnic groups, the Achí Maya are not seen as Quiché.

The Cakchiquel language is spoken by about 400,000 people in an area stretching from Guatemala City west to the northern shore of Lake Atitlán. Zutuhil has about 90,000 speakers in the vicinity of Lake Atitlán Other members of the Quicheana branch are Sacapultec, spoken by just under 40,000 people, mostly in the department of El Quiché, and Sipacapense, which is spoken by about 18,000 people in Sipacapa, San Marcos. The Annals of the Cakchiquel, written in Cakchiquel, is an important literary work dating from the 16th century AD. C. that refers to the history of the predominant classes of the Cakchiquels.

Poqom

The Poqom languages are closely related to the Quichean group, thus constituting a sub-branch in the Quichean-Mamean knot.

Pocomchí is spoken by 90,000 people in Purulhá, Baja Verapaz, and in the following municipalities of Alta Verapaz: Santa Cruz Verapaz, San Cristóbal Verapaz, Tactic, Tamahú, and Tucurú. Poqomam is spoken by about 30,000 people in several small nuclei, the largest of which is in the department of Baja Verapaz. There are also Poqomam speakers in El Salvador.

Phonology

Proto-Mayan Phonological System

In Proto-Maya, (the common ancestor of the Mayan languages, which has been reconstructed using the comparative method) roots with a CVC (consonant-vowel-consonant) syllabic structure predominate. -maya were monosyllabic except for some disyllabic nominal stems. Due to subsequent vowel loss, many Mayan languages now demonstrate complex consonant clusters on both syllable endings. Following Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman's reconstruction, the Proto-Mayan language has the following sounds; the sounds present in modern languages are largely similar to this root system.

| Previous | Central | Poster | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut. | Long | Cut. | Long | Cut. | Long | |

| High | ♪ | *i | ♪ | *u mark | ||

| Media | ♪ | *e | ♪ | *o | ||

| Low | ♪ | *a | ||||

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Gloss | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple | Implosive | Simple | Eyectiva | Simple | Eyectiva | Simple | Eyectiva | Simple | Eyectiva | Simple | ||

| Occlusive | ♪ | * | ♪ | ♪ | *tj | *tj | ♪ | ♪ | ♪ | *q. | * | |

| Africa | * | ♪ | * | ♪ | ||||||||

| Fridge | ♪ | * | * | ♪ | ||||||||

| Nasales | ♪ | ♪ | * | |||||||||

| Liquids | ♪ ♪ | |||||||||||

| Sliding | ♪ | ♪ | ||||||||||

Phonological evolution of Proto-Maya

The internal classification and subdivisions of the Mayan languages are based on shared changes between language groups. For example, the languages of the Western group (such as Huastecan, Yucatecan, and Cholano) all changed the Proto-Mayan phoneme */r / in [j], some Eastern Branch languages retained [r] (quicheanas), and others changed it to [ʧ] or, at the end of the word, [t] (Mamean). The shared innovations between Huastecan, Yucatecan, and Cholano show that they diverged from the other Mayan languages before the changes found in other branches had occurred.

| Proto-maya | Huasteco | Yucateco | Mopán | Tzeltal | Chuj | Kanjobal | Mam | Ixil | Quiché | Cakchiquel | Pocomam | Kekchí |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ♪[ra apostles] «Green» | [jagil] | [jaŭ] | [ja aviation] | [jagil] | [ja aviation] | [jagil] | []agil] | []a worship] | [rarit] | [r]ь] | [rarit] | [ra felt] |

| ♪[war] «dream» | [waj] | [waj] | [w]jn] | [waj] | [waj] | [waj] | [wit] (Aguacateco) | [wat] | [war] | [war] | [w]r] | [war] |

The palatized stops /tʲ’/ and /tʲ/ are not found in any of the modern families. In substitution of these original phonemes, the modern Mayan languages perform them in a particular way in the different groups of the family, allowing a reconstruction of these phonemes as palatized stops. In the eastern branch (Chujeano-Kanjobalano and Cholano) they are reflected in [t] and [t’]. In Mamean they are found as [ʦ] and [ʦ'] and in Quicheano as [ʧ] and [ʧ']. Yucatec stands out from other Western Mayan languages in that its palatized stops are sometimes changed into [ʧ] and sometimes [t].

| Proto-maya | Yucateco | Kanjobal | Poptí | Mam | Ixil | Quiché | Cakchiquel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ♪[tje booklets] «tree» | []e arcade] | [te.] | [te.] | []e bombing] | []e arcade] | []e bombing] | []e arcade] |

| ♪[tja covenant] «ash» | [ta coins] | [tan] | [tagil] | []a felt] | []a bombing] | []a felt] | []ax] |

The Proto-Mayan velar nasal *[ŋ] is reflected in the phoneme [x] of the eastern branches (quicheano-mameano); in [n] for Kanjobalan, Cholano and Yucatecan; in [h] for Huastecan; and it is preserved in its original form in Chuj and Jacalteco.

| Proto-maya | Yucateco | Kanjobal | Jacalteco | Ixil | Quiché |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ♪[GRUNTING] «tail» | [ne calling] | [ne] | [GRUNTS] | [xeh] | [xe booked] |

Other innovations

The internal classification of the Mayan languages is based on certain shared linguistic innovations. When a group of languages share a certain common mutation or phonetic change, it is postulated that they derive from a Mayan proto-variety that had undergone said mutation. Thus, the set of phonetic changes makes it possible to establish a phylogenetic tree where each change represents a branch point. The classification used in this article is based on these phonetic changes, which are sometimes present in some Mayan language subgroups but not in others.

The divergence of the Huastecan is reflected in a relatively high number of innovations not shared by other groups. Huastecan is the only branch in which */w/ Proto-Mayanse has changed to [b]. Huastec (but not Chicomuceltec) is also the only Mayan language to have a labiovelar phoneme /kʷ/; however, this is known to be due to a postcolonial development: comparing colonial Huastec documents to modern Huastec, it can be seen that the /kʷ/ originates originally from sequences of *[k] followed by a vowel rounded and an approximant. For example, the word for «vulture», which in modern Huastec is pronounced [kʷiːʃ], was written <guinea pig> in colonial Huastec and pronounced *[kuwiːʃ].

The grouping of the Cholan and Yucatecan branches is supported by the change from *[a] short to [ɨ]. All Cholan languages have changed the Proto-Mayan long vowels *[eː] and *[oː] a [ i] and [u] respectively. The independence of the Yucatecan group is evident because in all the Yucatecan languages the *[t] proto-Mayense gave place [ʧ] in word-final position.

Quichean-Mamean and some Kanjobalan languages have retained the Proto-Mayan uvular stops ([q] and [q']); in all other branches these sounds were combined with [k] and [k'], respectively. Thus, it can be said that the Quicheana-Mameana grouping rests above all on shared retentions instead of innovations.

Mameano is largely distinguished from Quicheano by the substitution of a string of phonemes, which replaced the consonant *[ r] for [t]; *[t] by [ʧ]; *[ʧ] by [ʈʂ] and *[ʃ] by [ʂ]. These retroflex fricatives and affricates later split into Kanjobalan through linguistic interactions. Within the Quichean branch, Cakchiquel and Zutuhil differ from Quichean in having replaced the final phonemes of Proto-Maya *[w] and * [ɓ] by [j] and [ʔ], respectively, in polysyllabic words.

Some other changes are general across the Mayan family are the following: the Proto-Mayan glottal fricative *[h ], which no language has preserved as such, has numerous reflexes in various daughter languages depending on its position within a word. In some cases lengthened a preceded vowel in languages that preserve vowel length. In other languages it gave way to [w], [j], [ʔ], [x] or disappeared.

Other sporadic linguistic innovations have occurred independently in other branches. For example, distinctive vowel length has been lost in Kanjobalan-Chujean (except for Mochó and Acateco), Cakchiquel, and Cholano. Other languages have transformed the length distinction into one of tense vs. loose vowels, later losing the distinction in most cases. However, Cakchiquel has preserved a loose, central schwa as a reflection of the vowel *[a]. Two languages, Yucatec and Uspantec, as well as a dialect of Tzotzil have introduced a tonal distinction in vowels, with high and low tones corresponding to the front length of the vowel as well as reflecting *[h] and *[ʔ ].

Grammar

The grammar of the Mayan languages is simpler than those of other Mesoamerican languages. From the point of view of morphological typology, the Mayan languages are agglutinative and polysynthetic. Verbs are marked by aspect or tense, the person of the subject, the person of the complement (in the case of transitive verbs) and by the plurality of the person. Possessive nouns are marked by the person of the possessor. There are no cases or genders in the Mayan languages. The morphosyntactic alignment is usually of the ergative type.

Word Order

It is conjectured that Proto-Maya had a basic word order of the Verb Object Subject type with possibilities of changing to VSO in certain circumstances, such as complex sentences, sentences where the object and the subject were of equal animacy and when the subject was defined. Modern Yucatecan, Tzotzil, and Tojolabal have a fixed basic order of the VOS type. Mameano, Kanjobal, Jacalteco, and a dialect of Chuj have a VSO order. Only Chorti has basic SVO word order. Other Mayan languages allow for the VSO and VOS word orders.

Numeral classifiers

When counting it is necessary to use the numeral classifiers that specify the nominal class of the objects that are counted; the numeral cannot appear without an accompanying classifier. The nominal class is usually assigned depending on whether the object is animate or inanimate, or according to the general shape of an object. Thus, when counting "flat" objects, a different form of numeral classifier is used than when counting round things, items oblongs or people. In some Mayan languages such as Chontal, the classifiers take the form of affixes attached to the numeral; in others such as Tzeltal, they are free forms. In Jacalteco the classifiers can also be used as pronouns. In Yucateco a classifying suffix is added to the number; when counting animated things, -p’éel is used; if rational beings or animals -túul are counted; for long-shaped objects use -ts’iit; and when trees are counted, -kúul.

There are also mensuratives, as the traditional measures used in the community are called to indicate the magnitude of what is counted. They are not inherent to nouns and have their origin in the grammaticalization of lexical morphemes. The meaning denoted by a noun can be significantly altered by changing the accompanying classifier. In Chontal, for example, when the -tek classifier is used with plant names, the objects being listed are understood to be entire trees. If in this expression a different classifier, -ts'it (for counting long, thin objects) is substituted for -tek, this conveys the meaning that only chopsticks or the branches of the tree are being counted:

| untek wop (a Jahuacte tree) "a jahuacte tree" | unts'it wop (a jahuacte) «a jahuacte tree stick» | ||||

| One- | tek | wop | One- | ts'it | wop |

| One... | «plant» | jahuacte tree | One... | "object.largo.slim" | jahuacte tree |

Possession

The morphology of Mayan nouns is quite simple: they decline for number (singular or plural), and, when possessed, for the person and number of their possessor.

Pronominal possession is expressed by a system of possessive prefixes attached to the noun, as in Cakchiquel ru-kej "his horse [for him or her]". Nouns can also take a special form that marks them as possessed.

For nominal possessors, the noun possessed is conjugated as possessed by a third-person possessor, and followed by the noun for possessor, e.g. eg the cakchiquel ru-kej ri achin "the horse of the man" (literally "his horse of him the man"). This type of formation is a major diagnostic feature of the Mesoamerican linguistic area and is repeated throughout Mesoamerica.

Mayan languages often contrast alienable and inalienable possession by varying the way the noun is (or is not) marked as possessed. The jacalteco, for example, contrasts the inalienable possessed wetʃel «my photo (in which they represent me)» with the possessed alienable wetʃele «my photo (taken by me)". The prefix we- marks first person singular possessor in both, but the absence of the possessive suffix -e in the first form marks inalienable possession.

Related Nouns

All Mayan languages that have prepositions usually only have one. To express position and other relationships between entities, use is made of a special class of "kin nouns". This pattern is also recurrent throughout Mesoamerica and is another diagnostic feature of the Mesoamerican linguistic area. In Maya, the most metaphorically related nouns are derived from parts of the body, so that "on top of", for example, is expressed by the word for head.

Relational nouns are owned by the component, which is the reference point of the relation, and the relational noun names the relation. Thus in the Maya it would say "the head of the mountain" (literally "his head of the mountain") to mean "on (the top of) the mountain." Thus in the classic Quiché of the Popol Vuh we read u-wach ulew "on the earth" (literally "his face of the earth").

Subjects and objects

The Mayan languages are ergative in their alignment. This means that the subject of an intransitive verb is treated similarly to the object of a transitive verb, but differently from the subject of a transitive verb.

The Mayan languages have two systems of affixes that are attached to a verb to indicate the person of their discussions. A system (often referred to in Maya grammars as system A) indicates the person of subjects of intransitive verbs, and objects of transitive verbs. They can also be used with adjective or noun predicates to indicate the subject.

| Use | Example | Example language | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject of an intransitive verb | x-ix-Okay. | Cakchiquel | «You guys. They entered" |

| Object of a transient verb | x-ix-ru-chöp | Cakchiquel | «He/she took You guys.» |

| Subject of a preaching adjective | ix-samajel | Cakchiquel | «You guys. They're workers. » |

| Subject of a noun preaching | 'antz- | Tzotzil | «You. You are a woman." |

Another system (system B) is used to indicate the person of subjects of transitive verbs, and also the possessors of nouns (including related nouns).

| Use | Example | Example language | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject of a transient verb | x-ix-ru-chöp | Cakchiquel | «He/she took you guys." |

| Possive marker | ru-kej ri achin | Cakchiquel | «The Horse of man (literally: "his horse man») |

| Related marker | u-wach ulew | Classic Quiché | "On the earth" (literally: "his the face of the earth”, e.g. “the face of the earth” |

Verbs

In addition to subject and object (agent and patient), the Mayan verb has affixes indicating aspect, tense and mood as in the following example:

| Aspect/mode/time | Prefix of class A | Prefix of class B | Raíz | Aspect/mode/voz | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k- | in- | a- | ch'ay | - | ||

| Incomplete | 1.a person sing. Patient | 2.a person sing. Agent | stroke | Incomplete | ||

| (Quiché) kinach'ayo «You are beating me» | ||||||

Tense systems in Mayan languages are generally simple. The jacalteco, for example, contrasts the past and the non-past, while the mam only has the future and the non-future. Aspect systems are usually more prominent. The mood does not normally form a separate system in Maya, but is instead intertwined with the tense/aspect system. Kaufman has reconstructed a tense/aspect/mood system for Proto-Maya that includes seven aspects: incompletive, progressive, completive / punctual, essential, potential / future, optional and perfective.

Mayan languages tend to have a rich system of grammatical voices. Proto-Maya had at least one passive construction as well as an anti-passive rule for minimizing the importance of the agent in relation to the patient. Modern Quiché has two antipassives: one that attributes the focus to the object and another that stresses the verbal action. Other voice-related constructions that occur in the Mayan languages are the following: mediopassive, incorporacional (incorporating a direct object in the verb), instrumental (promoting the instrument to object to position) and referential (a kind of applicative promotion of an indirect argument as a benefactive or recipient to the position of the object).

Stands and locators

In the Mayan languages, words are generally seen as belonging to one of four classes: verbs, statives, adjectives, and nouns.

Statives are a class of predicative words expressing a quality or state, whose syntactic properties fall in between those of verbs and adjectives in the Indo-European languages. As verbs, statives can sometimes be conjugated for person, but usually lack inflections for tense, aspect, and other purely verbal categories. Statives can be adjectives, positioners, or numerals.

Positioners, a class of words characteristic of, if not unique to, the Mayan languages, are statives with meanings related to the position or shape of an object or person. Mayan languages have between 250 and 500 different positional roots:

Telan ay jun naq winaq yul b'e.There's a man lying on the way.

There was a snake lying around in the entrance to the house yesterday.

Woqan hin k'al ay max ek'k'u.

I spent the whole day sitting

Yet ewi xoyan ay jun lob'aj stina.

In these three Kanjobal sentences, the positioners are telan ("something large or cylindrical lying down as if fallen"), woqan ("the person who sits on a chair-like object"), and xoyan ("coiled up like a rope or snake").

Word formation

The composition of noun roots to form new nouns is banal; there are also many morphological processes for removing nouns from verbs. Verbs also take highly productive derivational affixes of various kinds, most of which specify transitivity or voice.

Some Mayan languages allow the incorporation of noun stems into verbs, as direct objects or in other functions. However, there are few affixes with adverbial or modal meanings.

As in other Mesoamerican languages, there is widespread metaphorical use of roots denoting parts of the body, particularly to form locatives and related nouns such as Tzeltal/Tzotzil ti' na «door» (lit. «house mouth»), or the cakchiquel chi ru-pam «inside» (lit. «mouth his-stomach»).

Writing Systems

A complex script, used to write the Mayan languages in pre-Columbian times and known today from engravings at various Mayan archaeological sites, has been almost completely deciphered. This was an assorted, partly logographic and partly syllabic writing system.

In colonial times the Mayan languages began to be written in a script derived from the Latin alphabet; the spellings were developed primarily by missionary grammarians. Not all modern Mayan languages have standardized spellings, but the Mayan languages of Guatemala use a standardized, phonemic Latin orthography system developed by the Academy of Mayan Languages of Guatemala (ALMG). Orthographies for the languages of Mexico are currently being developed by the National Institute of Indigenous Languages (INALI).

Glyphic script

The pre-Columbian Maya civilization developed and used an intricate and versatile script; this is the only Mesoamerican script that can be said to have been nearly fully deciphered. Early civilizations established to the west and north of the patrias that also had scripts recorded in surviving inscriptions including the Zapotec, Olmec, and Zoque-speaking people of southern Veracruz and the western Chiapas area—but their scripts are still largely undeciphered. It is generally agreed that the Maya writing system was adapted from one or more of these earlier systems, and a number of references identify the undeciphered Olmec script as its most likely precursor.

In the course of deciphering the Maya glyphic script, it has become apparent that this was a fully functional writing system in which it was possible to express any sentence of the spoken language unequivocally. The system is best classified as logosyllabic, in which symbols (glyphs or graphemes) can be used as logograms or syllables.

The script has a complete syllabary (although not all possible syllables have yet been identified), and a Maya scribe would have been able to write something phonetically, syllable for syllable, using these symbols. In practice however, almost all inscriptions of any length were written using a combination of syllabic signs and word signs (called logograms).

At least two major Mayan languages have been confidently identified in glyphic texts, with at least one other language probably identified. An archaic language variety known as Classic Maya predominates in these texts, particularly in Classic period inscriptions from the southern and central lowland areas. This language is most closely related to the Cholan branch of the language family, modern descendants of which include Chol, Chorti, and Chontal.

Inscriptions in an early Yucatecan language (the Yucatecan language is a major survivor of that ancestor) have also been recognized or proposed, primarily in the Yucatán peninsula region and from a later period. Three of the four extant Maya codices are based on Yucatec. They have also conjectured that some inscriptions found in the Chiapas Highlands region may be in a Tzeltalan language whose present-day descendants are Tzeltal and Tzotzil. Other regional varieties and dialects are also presumed to have been used, but have not yet been used. identified with certainty.

The use and knowledge of Maya glyphic writing continued at least until the Spanish conquest in the 16th century d. C.. Bishop Diego de Landa described the use of glyphic writing in the religious practices of the Yucatec Maya, which he actively prohibited.

Modern Spelling

Since the colonial period, virtually all Mayan writing has used Latin characters. The spelling has generally been based on Spanish, and it is only recently that spelling conventions have been standardized.

The first widely accepted spelling rules were put into Yucatec Maya by the authors and contributors of the Diccionario Maya Cordemex, a project led by Alfredo Barrera Vásquez and first published in 1980. Subsequently, the Academy of Mayan Languages of Guatemala (known by its Spanish acronym ALMG), founded in 1986, adapted these standards to the 21 Mayan languages of Guatemala.

| Vocals | Consonants | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA |

| a | [a] | aa | [a memorial] | ä | []] | b' | []] | b | [b] | ch | []] | ch' | []] | h | [h] |

| e | [e] | ee | [e development] | ë | [ scrolls] | j | [x] | k | [k] | k' | [k’] | l | [l] | m | [m] |

| i | [i] | ii | [i mark] | ï | [grunting] | n | [n] | nh | [GRUNTS] | p | [p] | q | [q] | q' | [q] |

| or | [o] | oo oo | [o devoted] | ö | [ cheers] | r | [r] | s | [s] | t | [t] | t' | [t’] | tz | []] |

| u | [u] | uu | [u devoted] | ü | [chuckles] | tz' | []] | w | [w] | x | [CHUCKLES] | and | [j] | ' | [both] |

| |||||||||||||||

For languages that make a distinction between palato-alveolar and retroflex affricates and fricatives (Mam, Ixil, Tectitec, Avocado, Kanjobal, Poptí, and Acatec) the following system of conventions applies.

| ALMG | IPA | ALMG | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| ch | []] | ch' | []] |

| tx | []] | tx' | []] |

| xh | [CHUCKLES] | x | []] |

Lexical comparison

The following are the numerals in various Mayan languages:

GLOSA Huasteco Yucateco Cholano Qanjobal Mam Quiché proto-

MayaCh'ol de

TilaTzeltal

BachajónTzotzil

S. And Lar.Chuj

IxtatanQ'anjobal de

Santa Eulalia1 Hundred Hun Hun- Hun Hun xun χun χuun χun *χuun 2 čaab ka čavy- čeb čib čá pricep kab ' kab ' keb (b) 3 ! oš ## ošeb Åšib Åš ošeb " ooš ošib " * pocketoš(eb) 4 čee coin kam čambin- čaneb čanib čó/25070/ kaneb qaq kaχib *kacil(eb) 5 boo ho ho hoeb hoob hóp Heyb. χwe coin χo pocketob " *χo pocket(eb) 6 Åakak wak wambik- wakeb wakib wák waqeb waqib *waq(eb) 7 buuk ušuk wuk- hukeb hukub (up) uqeb wuqub *huq(ub) 8 wašik wašak wašambik- wašakeb wašakib wáxšak waʼaqeb wáχšaq waqšaqib *waqšaq(eb) 9 belehu Bolom Bolon- baluneb baluneb p '. b ' aloneb beleχu b " élχeb " *b ' elug(eb) 10 lahu lahun lahun- lahuneb lahuneb laxu laχoneb Laaχ laχu *laχu/25070/(eb) "

Literature

From the Classic period to the present day, a body of literature has been written in the Mayan languages. The earliest texts that have been preserved are largely monumental inscriptions, documenting authority, succession, and ascension, conquest, and calendrical as well as astronomical events. It is likely that other types of literature were written on perishable media such as bark codices, only four of which have survived the ravages of time and the Spanish missionaries' campaign of destruction.

Shortly after the Spanish conquest, the Mayan languages began to be written with characters from the Latin alphabet. Colonial-era literature in the Mayan languages includes the famous Popol Vuh, a mytho-historical narrative written in 19th-century Classical Quiché XVII d. C., but it is believed to be based on an earlier work written in the 1550s, now lost. The Title of Totonicapán and the theatrical work of the XVII century d. the Rabinal Achí are other notable early works in Quiché, the last in the Achí dialect.:small-caps;text-transform:lowercase">XVI d. Late C., which provide a historical narrative of the Cakchiquel, contain elements parallel to some accounts that appear in the Popol Vuh. The historical and prophetic accounts in multiple variations known collectively as the books of Chilam Balam are the primary sources of early Yucatec Maya traditions. The only surviving book of early lyric poetry, the Songs of Dzitbalché by Ah Bam, it comes from this same period.

In addition to these unique works, many early grammars of indigenous languages, called «artes», were written by priests and friars. Languages covered by these early grammars include Cakchiquel, Classical Quiché, Tzeltal, Tzotzil, and Yucatec. Some of these came with the indigenous language translations of the Catholic catechism.

Almost no literature in indigenous languages was written in the postcolonial period (after 1821) except by linguists and ethnologists collecting oral literature. The Maya peoples had remained largely illiterate in their mother tongues, learning to read and write in Spanish, absolutely. However, since the establishment of Cordemex (1980) and the Academia Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala (1986), mother tongue literacy has begun to spread and a number of indigenous writers have begun a new tradition of writing in Mayan languages. Notable among this new generation is the Quiché poet Humberto Ak'abal, whose works are often published in dual-language Spanish/Quiché editions.

Contenido relacionado

Grave accent

א

Joaquin