Mayan codices

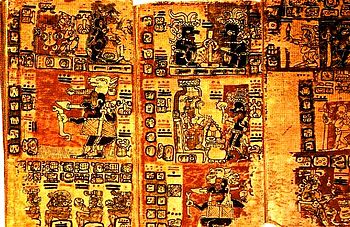

The Mayan codices are books from the Mayan culture of pre-Columbian origin, that is, before the conquest of America by the Europeans, in whose writing glyphs were used that are still being interpreted today.. The codices have been named taking as a reference the city in which they are located: the Dresden Codex, perhaps the most important and the most studied; that of Madrid; that of Paris and the Mayan Codex of Mexico, the latter located in the mountains of Chiapas, Mexico, which has only recently been recognized by some experts as authentic.

The Maya developed their type of paper relatively early, as there is archaeological evidence of the use of bark from the early 5th century. They called it huun.

«[...] Early in their history, the Mayas produced a kind of mantle from the inner part of the bark of certain trees, mainly from the wild fig or amate, and from the matapalo, another ficus. From this and with lime they formed paper, when it happened, we did not know it. The paper invented by the Mayas was superior in texture, durability and plasticity to the Egyptian papyrus. »Sandstrom and Sandstrom, Traditional Papermaking

History

There were several Mayan books written at the time of the conquest of Yucatán in the 16th century, but almost all of them were later destroyed by conquistadors and missionaries. In particular, those found in the Yucatan Peninsula were destroyed on the orders of Diego de Landa in July 1562. Together, the codices are a primary source of information on Mayan culture, along with inscriptions on stones and monuments, and stelae that survived to the present day and the frescoes of some temples.

Alonso de Zorita wrote that in 1540 he saw those books in the Guatemalan highlands that "narrated his history of more than eight hundred years ago and that were interpreted to him by very old indigenous people" (Zorita 1963, 271-2). Fray Bartolomé de las Casas lamented when he discovered that those books were destroyed and wrote: "These books were seen by our clerics, and I could even see remains burned by the monks apparently because they thought they could harm the indigenous people in matter of religion, since they were at the beginning of their conversion". The last to be destroyed were those of Tayasal, Guatemala, the last city in the Americas to be conquered in 1697.

Only four codices considered authentic survived to our times. These are:

- Dresden codex;

- Madrid Codex, also known as the Tro-Cortesian Codex;

- Paris Codex, also known as the Peresian Codex;

- Grolier Codex (Mayan Codex of Mexico for its new denomination)

Similar in form and structure, each is written on a single folded sheet nearly 7 meters long and 20 to 22 centimeters high, in sheets that are about 11 centimeters wide.

The authenticity of the Grolier Codex was not accepted by all Mayanists and for many years it was considered a forgery. Only recently, in 2016, have some experts worldwide concluded that it is not only authentic, but that it is physically the oldest of the four known.

The Dresden Codex

The Codex Dresdensis is kept at the Sächsische Landesbibliothek (SLUB), the state library in Dresden, Germany. It is the most elaborate of the codices. It is a calendar that shows which gods influence each day. Explains details of the Mayan calendar and the Mayan number system. The codex is written on a long sheet of brown paper that is folded to create 39 sheets, written on both sides. It was probably written by Mayan scribes just before the Spanish conquest. Somehow it made its way to Europe and was sold to the royal library of the Saxon court in Dresden in 1739.

On pages 46-50 he includes a Venus calendar, showing that the Maya had a very complex calendar associated with ceremonial ideas. On each of these pages there are four columns, each with thirty of the signs used in the 260-day calendar, called "tzolkin". Each of the signs represents the day in the tzolkin on which a particular position of one of the five Venus periods that complement eight years of 365 days has begun. The four columns on each particular page represent Venus in her four positions in the firmament: the superior conjunction, the morning star, the inferior conjunction, and the evening star. At the bottom of each page the number of days of each period is shown in Mayan numbers.

A German amateur, Joachim Rittsteig, linked to certain pseudoscientific theories, announced in 2011 that he had deciphered this codex which, he claimed, would allow him to locate a treasure of about eight tons of gold on tablets. As expected, this "discovery" it was denied by true experts on the subject shortly after.

In 1825-1826 the Italian Agostino Aglio made a copy of the Dresden Codex in black and white for Lord Kingsborough. (currently known as the Kingsborough Codex) He, in turn, published it in the book Antiquities of Mexico, which had nine volumes. Aglio had also prepared a color version, but Kingsborough died before it was published. The set of facsimile documents and copies of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican manuscripts that Lord Kingsborough included in his Original publication: Antiquities of Mexico.

The Madrid Codex

The Madrid Codex is in the Museo de América in Madrid, Spain. It has 112 pages, which are separated into two sections, known as the Troano Codex and the Cortesiano Codex. Both sections were reunited in 1888. Perhaps it was sent to Carlos I of Spain by Hernán Cortés, together with the Quinto Real. In the first relationship letter, Cortés describes: "More two books than the ones the Indians have here". López de Gómara in his chronicle describes that & # 34; they also put with these things some books of figures by letters, which the Mexicans use, taken as cloths, written everywhere. Some were made of cotton and paste, and others made of metal sheets, which serve as paper; sick thing to see But since they did not understand them, they did not appreciate them." When the first letter was sent, the Cortés expedition had already had exchanges with the Maya on the island of Cozumel, and with the Chontal Maya after the Battle of Centla.

The Paris Codex

Presumed to have been discovered in a dusty chimney corner of the Imperial Library of Paris (now National Library of France) after being acquired in 1832, it was made known in 1859 by Léon de Rosny. This codex, also known as the "Códice Peresianus", is currently in the Mexican Fund (Fonds Mexicain) of the National Library of France and is jealously guarded without public display. copies that have allowed their study. These prints, for the most part, derive from Léon de Rosny's 1887 chromolithographic version (like the 1968 Graz publication and Thomas Lee Jr.'s 1995 Chiapas publication) and the 1888 black and white photographic version.

The document has a total of eleven pages, of two of which all the details have been completely lost, and in the other nine the glyphs located in the central part are preserved reasonably intact, but all the motifs close to the four margins have been erased. The only complete discussion of the codex is Bruce Love's work in "The Paris Codex: Manual for a Maya Priest" of 1994, which refers its theme to ritual issues, corresponding to the gods and their ceremonies, prophecies, a calendar of ceremonies and a zodiac divided into 364 days.

The Grolier Codex, now called the Mayan Codex of Mexico

Unlike the other three codexes, which had already been found since the XIX century, the Grolier Codex was given to know in 1971. It is said that this fourth Mayan codex was found in a cave in the mountains of Chiapas in 1965; It belonged to Dr. José Sáenz, who showed it to the mayor Michael Coe at the Grolier Club in New York, which is why it is known by this name. It is a very poorly preserved 11-page fragment, and it has been determined that it must have belonged to a 20-page book. Each page measures 18 cm high by 12.5 cm wide.

Description: The pages of this codex are much less detailed than those of the other known ones. It is made of amate paper stuccoed on both sides (although only the obverse of each one is illustrated). On each page there is always a figure (presently identified as a god) facing the left side of the page and invariably holding a weapon, either a javelin or an atlatl, while in the other hand he holds a rope that always ends in a captive tied up The colors used are a hematite-based red, black, Mayan blue, a red, and a light brown. At the top of each page is a number, written in the Mayan slash-and-dot manner. At the bottom is a list of dates and calendrical calculations.

Controversies surrounding the Grolier Codex

Since its discovery in the 1960s, there have been controversies among scholars on the subject. On the one hand, some experts such as the American Michael D. Coe maintained the authenticity of the codex, while others, including the greatest scholar of Mayan culture at the time, J. Erick S. Thompson, considered it a forgery. One of the tests carried out on the codex was radiocarbon dating, which revealed a possible date of production in the 12th century; however, some authors still doubted its authenticity, stating that the document could be a forgery painted on authentic paper and arguing that - unlike the other known Mayan codices - the Grolier is written only on the obverse of the pages. This discussion continued through the 1980s and 1990s, with more scholars such as John B. Carlson, Yuri Knorozov, Thomas A. Lee, Jr., Jesús Mora Echeverría, George E. Stuart, and Karl Taube commenting on its authenticity. Later, already in 2005, Dr. Laura Elena Sotelo, a specialist in Mayan codices from the Center for Mayan Studies of the Philological Research Institute of the UNAM, declared that

"the evidence points to the fact that it is done in 1960, although there are still disputes about it."

It was not until 2016, when through an epigraphic, semiotic and iconographic study carried out by experts Stephen Houston, Michael D. Coe, Dr. Mary Miller and expert iconographer Karl Taube, a new effort was made to verify ultimately the authenticity of the artifact.

The main arguments in favor of the authenticity of the codex were:

- The calendaric variations in the Grolier - with respect to the other codexes - can be explained by "an accepted alternative function of mayan codex and regional or temporal variations in the mythology of the planet Venus".

- The use of sketches and grids in the codex is consistent with its equivalent in Mayan mural paintings.

- Studies at the Laboratory of the UNAM Institute of Physics revealed that modern materials were not used in the pigments with which the codex was painted, including the present Mayan blue, pigment whose formula had been lost in the colonial period, until re-discovered in 1993.

- From the iconographic point of view, one of the key arguments to validate this codex was the fact that the forgers would have to have known in advance the identification of the Maya-Toltec deities painted in the codex, in order to represent them; however these deities were only identified until the 1980s, which makes it impossible to have painted them properly at the time when the codex was discovered.

These arguments, coupled with previous radiocarbon dating (which yielded a date of manufacture of the amate paper on which the codex is painted, of between 1257 ± 110 and 1212 ± 40) tilted the opinion of the international scientific community in in favor of its veracity: the Codex is not only authentic, according to this new investigation, but it is physically older than the other three (the others are copies made in the post-classical period of classic originals and it is theorized that it is painted in a rustic way - using only numbers and no text - since it seems that its use was more casual, the product of a less educated society than the classical one.

Although controversy regarding the authenticity of the codex has been sustained due to objections raised against the procedure by the authors of the 2016 study, more recent expert opinions tend to leave such authenticity as a proven fact. Accordingly, the codex will be incorporated into the Memory of the World program, based on the appointment granted by UNESCO and the name by which the codex will be known in Mexico will be Códice Maya de México.

Form of creation

For years it was thought that the codices were made of maguey fiber, but in 1910 R. Schwede determined that they were made by a process that used the inner bark of a variety of the fig tree, known as amate. Later the bark was treated with a layer of stucco on the surface, on which it was written with brushes and ink. The black ink was carbon black from soot, the red tones were made from hematite (iron oxide), a type of deep blue paint (Mayan blue), and there were also greens and yellows. The codices were written on long strips of this paper and folded accordion-style. The pages were about 10 by 23 cm (4 by 9 inches).

The "Perez Codex"

This is not a codex like the previous ones, since it is not a primary document, although it also has great historical value. Códice Pérez is the name that Bishop Crescencio Carrillo y Ancona gave to the work carried out at the beginning of the 19th century by the Mayanist researcher Juan Pío Pérez, consisting of a series of fragmentary copies of various books from Chilam Balam, compiled with the purpose of carrying out the chronological studies undertaken by the investigator of the Mayan culture in Yucatan.

This codex also contains a loose Maní almanac and some other transcriptions of various documents, apart from the Chilam Balam books noted above, particularly the Ixil, Maní, and Kaua books.

According to the historian and also Mayanist Alfredo Barrera Vásquez:

"Códice Pérez's name lends itself to confusion as a fragment of it has been called "Pérez Codex". The real title that Juan Pío Pérez gave him is: Main epochs of ancient Yucatan history... In addition to the so-called fragment (Pérez Codex), there is the pre-Courtesian manuscript "Codex Peresianus", which has nothing to do with Pio Pérez, or with the books of Chilam Balam, in a direct way. The "Codex Peresianus", or Paris Codex, is kept in the National Library of Paris and is, of course, an original hieroglyphic document.

Contenido relacionado

Carlism

Lautaro Lodge

Kingdom of Navarre