Maus

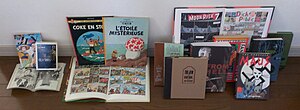

Maus: A Survivor's Tale is a novel graphic completed in 1991 by American cartoonist Art Spiegelman. It is an alternative comic published in installments between 1980 and 1991 in Raw magazine, an avant-garde comics publication headed by Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly. The work, of almost 300 pages, was published in two parts: My Father Bleeds History (My Father Bleeds History, 1986) and And there my problems began (And Here My Troubles Began, 1991), later united in a single volume. The story develops from the author's own experiences and interviews with his father, who narrates his life as a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor. The book makes use of postmodernist techniques and employs conventional resources, typical of classical fables, by representing different human groups as different types of animals: Jews are mice, Germans are cats, non-Jewish Poles appear as pigs, etc.. Maus is a book of memoirs, biographical, historical, autobiographical and one could even say that it is a mixture of genres.

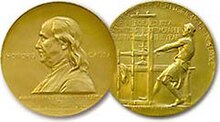

A three-page strip, drawn by Spiegelman in 1972, was the starting point for the author to interview his father about his life during World War II. The taped interviews became the basis for the graphic novel, which Spiegelman began in 1978. In 1992, it became the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize. It also received other prestigious awards and spawned one of two pathways. of the contemporary graphic novel, the independent and autobiographical, as opposed to the superheroic and fictional of Watchmen and Batman: The Dark Knight Returns.

In Maus Art Spiegelman tells the true story of his father, Vladek Spiegelman, a Polish Jew, during World War II, as well as the complicated relations between father and son during the process of making the comic, already in the United States, where Art's parents arrived after the war. The story takes place on the one hand in Rego Park (New York), where Vladek Spiegelman tells his story to his son Art, who is developing a comic. And, on another plane, it is narrated in Vladek's flashbacks about his experiences during the war. According to Rosa Planas, "it is a capital work on the Holocaust for many reasons: the originality of the treatment in the form of overlapping stories, the use of flash-back, the chosen medium (comics) and also the fable character that entails the fact that the protagonists are animals that stage human behavior".

In the present tense narrative, which begins in 1978 in Rego Park, New York, Spiegelman talks with his father about his experiences during the Holocaust with the intention of gathering material for his project Maus. In the narration in the past tense, Spiegelman shows these experiences, beginning with the years before World War II. Most of the story revolves around Spiegelman's complicated relationship with his father and the absence of his mother, who committed suicide when he was twenty. Her husband, Vladek, destroyed her writings on Auschwitz. Spiegelman resorts to a minimalist drawing style, while innovating in the arrangement of pages and panels, in rhythm and structure.

Synopsis

Most of the book oscillates between two timelines. In the present tense narration storyline, Spiegelman interviews his father, Vladek, in Rego Park, New York in 1978- 1979. The story that Vladek tells is shown as past tense narration; it begins in the mid-1930s and continues until the end of the Holocaust in 1945.

In 1958, in Rego Park, a young Art Spiegelman complains to his father that his friends have left without him. His father responds in non-standard English: "Friends?" Your friends? If they were locked up for a week in a room without food... then you'd see what friends are!"

As an adult, Art visits his father, whom he has grown estranged from. Vladek has married a woman named Mala after Art's mother, Anja, committed suicide in 1968.

Art wants Vladek to reminisce about his Holocaust experience. Vladek tells him about his time in Częstochowa, describing how he came to marry Anja from a wealthy family in 1937 and moved to Sosnowiec to open a factory. Vladek pleads with his son not to include this part of the story in the book, and Art reluctantly agrees. Anja suffers a mental breakdown from postpartum depression after giving birth to their first child, Richieu, and the couple attend. to a mental institution in Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia for her to recover. After her return, political and anti-Semitic tensions rise until Vladek is recruited just before the Nazi invasion. Vladek is captured at the front and forced to work as a prisoner of war. After being released, he finds out that Sosnowiec has been annexed to Germany, so he is taken across the border into the Polish protectorate. He manages to sneak across the border and is reunited with his family.

During one of Art's visits, he finds that a friend of Mala's has sent the couple one of the underground magazines where Art had collaborated with the comic strip Prisoner on the Planet of Hell. Despite Mala having tried to hide it, Vladek finds it and reads it; In the comic, the suicide of Art's mother three months after he was released from the psychiatric hospital traumatizes him, and he ends up depicting himself behind bars, saying: "You killed me, Mommy! And you let me take the blame!!!" Despite the fact that he brings back painful memories, Vladek admits that it was good to bring the matter up that way.

In 1943, Jews were transferred from the Sosnowiec ghetto to Srodula, a nearby town, although they were made to march daily to work in Sosnowiec. The family is divided, as Vladek and Anja send Richieu to Zawiercie with his aunt, with whom they think he will be safe. However, as the raids increase and more Jews are sent to Auschwitz, the aunt decides to poison her children, Richieu, and herself, to escape the Gestapo. In Srodula, many Jews—including Vladek—build bunkers to hide from the Germans. Vladek's bunker is discovered and he is sent to a 'ghetto within the ghetto', an area separated by barbed wire. Vladek and Anja's family are left without their last belongings. Srodula is emptied of Jews, except for a group with whom Vladek hides in another bunker. When the Germans march, the group splits up and leaves the ghetto.

In Sosnowiec, Vladek and Anja move from one hideout to another, making occasional contact with other Jews in hiding. Vladek goes undercover in search of supplies, posing as a non-Jewish Pole. After arranging with smugglers to leave the country for Hungary, it turns out to be a trick: the Gestapo arrests them on the train and takes them to Auschwitz, where they are separated until after the war.

Separately, Art asks about Anja's journals, since Vladek had told him they contained his mother's experiences during the Holocaust. They are the only way to find out what happened to her after her separation from Vladek at Auschwitz. Vladek reveals to Art that they said, "I hope my son, when he grows up, will be interested in this," but he also admits that he burned them after Anja's suicide. Art is enraged, calling Vladek a "murderer".

The story jumps to 1986, after the first six chapters of Maus were published in a single volume. Art is overwhelmed by the unexpected attention the book is receiving and admits to being "totally blocked". Art talks to his psychiatrist—Paul Pavel, a Czech national and fellow Holocaust survivor—about the book. Pavel suggests that since those who perished in the camps won't be able to tell their stories, "perhaps it's better not to tell any more stories." Art replies with a quote from Samuel Beckett: "Every word is an unnecessary blot on the silence and nothingness," but then realizes that "on the other hand, he said it."

Vladek talks about his hardships in the camps, about starvation and mistreatment, about his ability to get by, about ways to avoid selektionen — the process of selecting prisoners for more jobs or to execute them— etc. Although dangerous, Anja and Vladek manage to exchange messages occasionally. As the war progresses and the German front is forced back, prisoners are transferred from Auschwitz -in Poland- to Gross-Rosen -inside the Reich-, and then to Dachau, where the hardships only increase and Vladek falls ill with typhus.

The war ends, the prisoners in the camps are released, and Vladek and Anja are reunited. The book ends with Vladek turning in his bed and saying to Art: "I'm tired of talking, Richieu, enough stories for now..." The final image shows Vladek and Anja's grave; Vladek died in 1982, before the book was completed.

Main characters

- Art Spiegelman: Art (1948) is a hysterist and intellectual. It is presented as egocentric, neurotic and obsessive, rabid and given to self-compassion. Art treats his own problems and the inherited from his parents through psychiatric help, which continues after completing the book. He maintains a tense relationship with his father, Vladek, for whom he feels dominated. At first, he shows little sympathy for the difficulties faced by his father, but as history advances his interest.

- Vladek Spiegelman: Vladek (Czestochowa1906–New York 1982) is a Jewish Holocaust-surviving Polish who later moved to the United States in the early 1950s. It is expressed in an incorrect English, proper to a foreigner, and appears as an undivided as a tacaño, austere, of an anal-retentive personality, anxious and obstinate, traits that could have served him to survive in the fields, but that draw their boxes from their family. It shows racist attitudes without realizing, as when Françoise picks up an African-American autostopian and Vladek expresses his fear that he will rob them.

- Mala Spiegelman: Mala (1917–2007) is the second wife of Vladek, who makes her feel that she will never be able to equal Anja. Although he is also a survivor and speaks to Art throughout the book, the character of Art does not make any attempt to learn from his Holocaust experience.

- Anja Spiegelman: Also a Polish Holocaust-surviving Jew, Anja (Sosnowiec 1912– New York 1968) is the mother of Art and the first wife of Vladek. Nervous, submissive and dependent, had his first nervous crisis after giving birth to his first child. He sometimes told Art about the Holocaust when he was young, even though his father didn't want him to know about it. He committed suicide by cutting his wrists in a bathtub in May 1968, without leaving a suicide note.

- Françoise Mouly: Françoise (1955) is married to Art. He is French and became Judaism to please Vladek. Art shows doubts about whether it should be represented as a Jewish mouse, a French frog, or some other animal.

The drawing

Art Spiegelman uses anthropomorphic animals: mice to represent the Jews (Maus means mouse in German), cats for the Germans, pigs for the Poles, frogs for the French, deer for the Swedes, and dogs for the Americans, as well as fish for the British. Apart from the evident fabulistic component, the use of this convention of collective representation visually emphasizes the "deindividuation" fostered by the Holocaust, with the reduction of the individual to a mere national, ethnic or racial identity (eg, Germans, Jews, Poles) that determines her destiny in that historical context. As Spiegelman himself has admitted, this convention is also inspired by a reappropriation of American cartoons (cartoons), such as "Tom & Jerry", very influential in the film and television culture of his childhood.

The work can also be interpreted as a claim to the autonomy of comics, demonstrating that it can address any topic without abandoning its graphic conventions.

The drawing is in black and white, with an angular and nervous line inspired by woodcuts from the beginning of the centuryand which, within the avant-garde work of Spiegelman (very influenced by expressionism), is contained.

The translation

In the original English novel, Vladek Spiegelman uses idiosyncratic English that reveals his Jewish background as a regular Yiddish speaker. Both in the Argentine editions and in the Spanish edition of Planeta DeAgostini, produced by Roberto Rodríguez, 2001, this trait disappeared. On the contrary, in the Penguin Random House edition, with translation by Cruz Rodríguez Juiz, 2007, this characteristic trait of the character is maintained, using resources typical of the Spanish language that try to reflect the original way of speaking about Vladek: the character confuses tenses, grammatical genders, the use of ser and estar, prepositions. In the original North American version, the peculiarities of Vladek's speech, like that of other immigrants of Jewish origin from Eastern Europe, are usually limited to the preposition of some verbal complements, misuse of modal verbs, etc., but his English only supposes a very punctual and recognizable deviation from the norm.

Translations into Spanish and other peninsular languages

- Maus: The story of a survivor (V/1989). Edited by Norma Editorial and Muchnik Editors in soft cover with flaps. Translated from English by Eduardo Goligorsky. (ISBN 84-7669-093-2). In this edition only the first six chapters originally published in Raw magazine, corresponding to the original, were collected. Maus I

- Maus: History of a Survivor (1994). Edited by Emecé Editors (Argentina) in soft cover with flaps, in two volumes (Maus I and Maus II). Translation by Argentine writer César Aira. Reprinted edition by Editorial Planeta Mexicana (Mexico DF, 2009) under the label Emecé.

- Maus: Relation of a Survivor (XI/2001). Edited by Planet DeAgostini, in hard cover, in his Trazado collection. Translated from English by Roberto Rodriguez. In this edition the two parts of the work are collected. At its first edition, of 6,000 copies, and in which the covers had been pixelated due to a printing error, three more followed in which the error was already corrected (ISBN 84-395-9159-4).

- Maus: Relat d'un supervivent (2003). Edited by Inrevés SLL (Palma), with several edits. Translated to Catalan by Felipe Hernández (ISBN 84-932615-2-1).

- Maus: Relato dun survivente (2008). Edited by Inrevés SLL (Palma). Translated to the Galician by Diego García Cruz. ISBN 978-84-935415-4-5).

- Maus (VI/2007). Edited by Mondadori. Translated by Cruz Rodríguez Juiz (ISBN 84-397-2071-3). It maintains greater fidelity to the original and reproduces the peculiarities of Vladek's speech.

Awards and nominations

Awards

- 1988 International Prize for the Angulema Comic Festival

- 1988 Urhunden Award for Best Foreign Album

- 1990 Max & Moritz Award, Special Prize

- 1992 Pulitzer Prize

- 1992 Eisner Award for Best Republished Graphical novel

- 1992 Harvey Award for Best Republished Graphic novel

- 1993 Literary Fiction Award Los Angeles Times

- 1993 International Prize of the Angoulême Comic Festival for the best foreign comic

- 1993 Urhunden Award for Best Foreign Album

Candidacies

- 1986 National Critics Circle Award

- 1992 National Critics Circle Award

Contenido relacionado

Indonesian economy

Indonesian history

Swiss flag