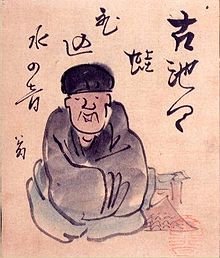

Matsuo Basho

Matsuo Bashō (Japanese: 松尾芭蕉) born Matsuo Kinsaku (Ueno, 1644 - Osaka, November 28, 1694), was the most famous poet of the Japan Edo period. During his lifetime, Bashō was recognized for his works on the Haikai no renga (俳諧の連歌). He is considered one of the four great masters of haiku , along with Yosa Buson, Kobayashi Issa and Masaoka Shiki; Bashō cultivated and consolidated the haiku with a simple style and a spiritual component. His poetry achieved international renown and in Japan many of his poems are reproduced on monuments and traditional places.

Bashō began to practice the art of poetry at an early age and later became part of the intellectual scene of Edo (now Tokyo), quickly becoming a celebrity throughout Japan. Despite being a teacher of poets, at certain times he renounced the social life of literary circles and preferred to travel the entire country on foot, even traveling through the northern part of the island, a sparsely populated territory, in order to find sources of inspiration for his writings.

Bashō does not break with tradition but continues it in an unexpected way, or as he himself comments: "I do not follow the path of the ancients, I seek what they sought". Bashō aspires to express with new means the same concentrated feeling of great classical poetry.His poems are influenced by a first-hand experience of the world around him, and he often manages to express his experience with great simplicity.. Of the haiku Bashō had said that it is "simply what happens in a given place and at a given time".

Biography

Early Years

Bashō was born Matsuo Kinsaku (松尾金作) around 1644, somewhere near Ueno, in Iga Province (present-day Mie Prefecture). His father, Matsuo Yozaemon, was a low-ranking samurai. rank, with few resources, in the service of the powerful Todo family, and wanted Bashō to pursue a career within the military. He had an older brother and four sisters. Biographers traditionally believe that he worked doing chores in kitchens. However, as a child he became a page in the service of Todo Yoshitada (藤堂良忠), heir to the Todos and two years older than Matsuo. Under Yoshitada's protection, Bashō was able to train in haikai composition under Master Kitamura Kigin (1624-1705), a poet and critic of the Teitoku school of haikai. Young Yoshitada and Bashō, despite their great difference in social class, would share a love for haikai no renga , a form of literary composition that is the fruit of cooperation between various poets. The sequences begin with a verse in the format 5-7-5 blackberries; this verse was named hokku, and later haiku, and was produced as a small independent piece. The hokku continued with an addition of 7-7 mulberries by another poet. Both Yoshitada and Bashō gave each other the corresponding I have (俳号), pen names haikai, Bashō's was Sobo (宗房), which is simply constructed from from the on'yomi transliteration of his samurai name, Matsuo Munefusa (松尾宗房); Yoshitada's pen name was Sogin. In 1662 Bashō's first poem was published; in 1664 a compilation of two of his hokku was printed, and in 1665 Bashō and Yoshitada composed a hundred verses renkus.

In 1666 Yoshitada's sudden death marked the end of Bashō's quiet serf life in the setting of a traditional feudal society. No documentary record of this period exists, but it is believed that Bashō considered becoming a samurai and left home. Biographers have proposed possible motivations and fates, including the possibility of a romance between Bashō and a Shinto miko named Yute (寿贞), but this relationship is unlikely to be true. Bashō's own references to this time are few; later he recalled that "for a long time I coveted the fact of being a civil servant and having a corner of land", and also, "there was a time when I was fascinated with the forms of homosexual love", but there is no sign that he was referring to a true fictional obsession or something else. He was not sure if he could become a full-time poet; he commented that "alternatives were fighting in my head and my life was full of restlessness". His indecision may have been influenced by the still relatively low artistic and social status of renga and the haikai no renga. In any case, he continued to create his poems that would be published in anthologies in the years 1667, 1669 and 1671. In 1672 he published his own compilation of the works carried out by himself and other authors of the Teitoku School, Kai ōi (貝おほひ). In the spring of that year, he settled in Edo to further study poetry.

Renowned Writer

Nihonbashi literary circles quickly recognized the value of Bashō's poetry for its simple and natural style. In 1674 he became part of the inner circle of haikai practitioners and secretly received teachings from Kitamura Kigin (1624-1705).At that time he wrote this hokku in homage to the Tokugawa shogun:

kabitan mo / tsukubawasekeri / kimi ga haru(1678)

- The Dutch, too, / kneel before his lord / spring to his reign.

He adopted a new I have, Tosei, and by 1680 he was already dedicating himself to the profession of poet full-time, being the teacher of twenty disciples. The same year Tosei-Montei Dokugin-Nijukasen((桃青门弟独吟二十歌仙), a work containing the best poems of Tosei and his twenty disciples, which showcased the artist's talent, was published. In the winter of 1680, he made the surprising decision to move across the river to Fukagawa, away from people and choosing a more solitary life. His disciples built him a rustic hut and planted a banana tree (芭蕉, bashō or Musa basjoo) in the courtyard, giving a new have to the poet who would henceforth be called Bashō, and his first permanent home.He loved the plant very much and it bothered him very much watching plants of the genus Miscanthus, a typical Fukagawa Poaceae, grow around his banana tree.

Bashō UETE / Mazuria nikumu ogi no / Futaba kana(1680)

- For my new banana plant / the first sign of a thing I hate / an eulalia outbreak!

During this time of retirement, Bashō's work underwent a new stylistic shift. Abandoned by the "madding crowd" of the city and, with it, the parodic and transgressive style of the Danrin school that prevailed in the 1970s, attention is now directed to the Chinese classics, above all to the texts of the Zhuangzi and the poetry of Du Fu and Su Dongpo (Su Shi), with whom he shared the retreat experience. The Bashō production opened a new path in the history of haikai: it was a poetry intimately linked to the poet's personal experience, although mediated by a continuous dialogue with classical Chinese poetry and with the work of other Japanese retirement poets like Saigyo or Sogi. As a result, the vital experience of abandonment and poverty converges with the wabi-sabi aesthetic. The presence of everyday objects (a piece of dried salmon, the dripping of rain in a bucket...) take center stage as poetic motifs exploring "the high in the low, the spiritual in the mundane, wealth in poverty"

Bashoo nowaki shite / tarai ni ame wo / kiku yo kana(1680)

- The temporary roof / my banana / all night I hear / droplets on a bucket.

Despite his success, he lived unsatisfied and lonely. He began to practice Zen meditation, but it does not appear that he was able to regain his peace of mind.In the winter of 1682 his cabin caught fire and shortly thereafter, early in 1683, his mother died. With all these events he traveled to Yamura to stay at a friend's house. In the winter of 1683 his disciples gave him a second cabin in Edo, but his mood did not improve. In 1684 his disciple Takarai Kikaku published a collection of his and other poets' poems, Minashiguri (虚栗), Wrinkled Chestnuts. year, he left Edo for the first of his four great journeys.

Travelling poet

Traveling in medieval Japan was very dangerous and Bashō's expectations were pessimistic; he believed that he could die in the middle of nowhere or be killed by bandits. As he progressed on the trip, his mood improved and he found himself comfortable doing what he did; He met many friends and began to enjoy the changing landscape and seasons, his poems became less introspective and reflected observations of the world around him:

uma wo sae / nagamuru yuki no / ashita kana(1684)

- Even a horse / my eyes stop at it / snow in the morning.

Along with the vital experience, the trips also represent for Bashō an aesthetic experience of encounter with places already sanctioned by the tradition of classical poetry waka (utamakura) (the cherry trees of the Yoshino hills, the Taima temple, the tomb of the lady Tokiwa, the plains of Musashi…) present in his poems since his first travel diary.

The first journey to the west took him from Edo to the distant province of Omi. Following the famous Tokaido route along the Pacific coast, he gazed at Mount Fuji, until he reached Ise Bay, where he visited the famous Shinto temple. After resting for ten days in Yamada, he visited his hometown of Uedo and the famous cherry trees on Mount Yoshino. in Nara. In Kyoto he met with his old friend Tani Bokuin and several poets who considered themselves his disciples and asked him for advice. Bashō showed them contempt for the contemporary style existing in Edo and even criticized their work Wrinkled Chestnuts, saying that it "contains many verses that are not even worth talking about". During his time in Nagoya he met with local poets and disciples, composing five kasen that would form part of the work Winter Sun (Fuyu no hi). This work would inaugurate the new Minashiguri style, where classical Chinese poetry was established as an aesthetic reference. He returned to Edo in the summer of 1685 and devoted time to writing more hokku and left comments about his own life:

Toshi kurenu / kasa kite waraji / hakinagara(1685)

- A year has passed / a traveler shadow on my head / straw sandals at my feet.

At this time he would record the experience of this first trip in the book Diary of a Skull in the Wild (Nozarashi Kiko, 野ざらし紀行), although he would not finish it until 1687. When he returned to Edo, to his cabin, he happily resumed his work as a poetry teacher; however he was already making plans for another trip.At the beginning of 1686 he composed one of his best haiku, one of the best remembered:

rau ike ya / kawazu tobikomu / mizu no oto(1686)

- An old pond / a frog that jumps: / the sound of the water.

Historians believe this poem became famous very quickly. In the same month of April, the Edo poets met at Bashō's hut to compose haikai no renga based on the theme of frogs; it seems that in a tribute to Bashō and his poems, they placed it at the top of the compilation.

Bashō remained in Edo, continued his master's degree, and entered literary contests. He did a couple of trips. The first was an excursion in the autumn of 1687 to participate in the tsukimi, the festival to celebrate the autumn moon, accompanied by his disciple Kawai Sora and the Zen monk Sōha that he would pick up on his Journey. to Kashima (Kashima Kiko) (1687). In November he would undertake a longer trip when, after a brief stay in Nagoya, he returned to his native Ueno to celebrate the Japanese New Year, the fruit of which would emerge Notebook in a Backpack (Oi no Kobumi , 1687). Back in Edo, he would visit Sarashina in Nagano to contemplate the harvest moon, an experience that he would recount in The travel diary to Sarashina (S arashina Kiko , 1688).

Back home, in his cabin, he alternated solitude with company, going from rejecting visitors to appreciating their company. At the same time, he enjoyed life and had a subtle sense of humor, as reflected in in the following hokku:

iza Sarabia / yukimi ni korobu / tokoromade(1688)

- Now, we leave / to enjoy the snow... until / slip and fall!

Oku no Hosomichi

Bashō's planning for another long private journey culminated on May 16, 1689 (Yayoi 27, Genroku 2), when he left Edo with his disciple Kawai Sora (河合曾良); It was a trip to the northern provinces of Honshu, the main island of the Japanese archipelago.

From the first lines of the book, Bashō presents himself as an anchorite poet and half-monk; both he and his traveling companion walk the roads wearing the habits of Buddhist pilgrims; His journey is almost an initiation and Sora, at the beginning of the path, shaves his skull. Throughout the trip they were writing a diary that is accompanied by poems and, in many of the places they visit, the local poets receive them and compose the corresponding collective haikai no renga with them.

By the time Bashō arrived in Ōgaki, Gifu Prefecture, he had already completed his journey's record. It took him about three years to revise it and he wrote the final version in 1694, with the title of Oku no hosomichi (奥の細道) or Path to Oku . The first edition was published posthumously in 1702. It was immediately a commercial success and many other itinerant poets followed his journey. He begins the diary with the following words: Months and days are travelers of eternity. The year that is leaving and the year that is coming are also travelers. It is often considered to be his best work, with some hokku such as the following:

araumi ya / Sado ni yokotau / Amanogawa(1689)

- Sea agitated / extends to Sado / The Milky Way

At the end of the journey, and of the book, Bashō reaches the town of Ohgaki from where he finally embarks to return home. The work ends with the last haiku, difficult to translate. We add four proposals:

hamaguri no / futami ni wakare / yuku aki zo(1689)

- Like the clam / in two walnuts, I give up / you with the fall. ( Cabezas García )

- From the clam / separate the fences / towards Futami I go with the autumn. ( Eighth Peace )

- How clams the separation; to Futami / march in autumn. ( Rodríguez-Izquierdo )

- Starting towards Futami / dividing me like a clam and the fences / we go with the fall. ( Donald Keene )

Last years

After resting for a couple of months in his hometown, Bashō, accompanied by his disciple Rotsu, visited Nara in January 1690 to attend the famous Kasuga festival. In February he returned to Ueno, staying at the castle of the lord of Tangan. During the month of April, the first mention of the poetic principle of karumi (lightness) is documented, which would guide his poetic production in this last phase of his life. Once again on his way, he headed for Zeze, a town to the shores of Lake Biwa, where he would spend the summer in a cabin built by his disciples. Around this time his health problems began. From there he would make short trips around the area.

When he returned to Edo in the winter of 1691, Bashō lived in a new cabin, surrounded by his disciples, located in a neighborhood to the northwest of the city called Saga. There he wrote the Saga Diary ( Nikki Saga ). This time he was not alone, with him he had a nephew and his friend, Yute, who were recovering from an illness. He received a large number of visitors while helping his disciples Kyorai and Bonchō prepare Sarumino (1691), considered the best anthology of the Bashō school. Sensing an improvement in his health, he once again left Edo to live in a new hut near the Gishu temple, one of his most beloved places. After a long journey accompanied by his niece Tōri, he would return to Edo in December 1691.

Back in the capital, Bashō began to feel tired of the literary circles and popularity that had trivialized the composition of haikai. Little by little he was reducing his public activity, remaining with a small group of faithful disciples among which were Sanpu and Sora. They were the ones who built him a new cabin in a place not far from his original residence in Fukugawa, where they would transplant the famous banana tree.

Bashō was still unwell and restless. He wrote to a friend and commented that 'worried about others, I have no peace of mind'. The death of his beloved nephew Toin, whom he had taken with him on his last journey, plunged him in deep sadness. Around this time he also began to care for a young woman, named Jutei, with her three children. Some biographers relate Jutei to a love affair that the poet had in his youth. With the arrival of autumn he gradually resumed his social life, although he was not physically recovered.

Early in the new year, Bashō began planning a new trip. Aware of his state of health, he wanted to say goodbye to his relatives in Ueno. As he would write to a friend, he "felt that he was nearing the end of it." In addition, the disputes between his disciples in Nagoya and Osaka had him worried. In this year's poems, a new poetic style was evident, characterized by what he would call karumi (lightness, lightness). Leaving Jutei with his two daughters in his hut, Bashō left Edo for the last time in the summer of 1694 accompanied by Jirobei, Jutei's son. Passing through Nagoya, he arrived at Ueno on June 20. Despite his exhaustion and his state of health, he arrived in Kyoto and settled in Villa Rakushi. There he received the news of Jutei's death. His school was gaining more and more prestige. Proof of this were the appearance of two anthologies Betsuzashiki and Sumidawara.

After revisiting Kyoto, return to Edo at the end of August. The desire to spread the new style, marked by the karumi , made him set off again for Osaka, where he arrived exhausted and very ill. After a brief improvement, suffering from stomach problems, he passed away peacefully, surrounded by his disciples on November 28. Bashō is buried in Otsu (Shiga Prefecture) in the small Gichu-ji temple (義仲寺), together with the warrior Minamoto Yoshinaka. Although he did not compose any poems on his deathbed, the last poem written during his last illness has come down to us and is considered his farewell poem:

tabi ni yande / yume wa karen wo / kake meguru(1694)

- Fall sick during the trip / my dream wandering strike / on a dry lawn field.

Influence and literary criticism

Rather than clinging to the formulas of kigo (季语), a form that is still popular in present-day Japan, Bashō aspired to reflect emotions in his hokku and the environment that surrounded him. Even in life his poetry was highly appreciated; after his death this recognition increased. Some of his students, and notably Mukai Kyorai and Hattori Dohō, collected and compiled Bashō's own views on his poetry.

The list of disciples is very long. On the one hand, there was the so-called group of the "ten philosophers", among which it is worth highlighting Takarai Kikaku; on the other hand, a diversity of followers, among which it is worth noting Nozawa Bonchō, who was a doctor.

During the 18th century the appreciation of Bashō's poems rose even more fervently, and commentators such as Ishiko Sekisui Moro and Nanimaru traveled far to find references to his hokku, searching for historical events, medieval documents and other poems. These admirers were lavish in their praise of Bashō and concealed the references; it is believed that some of the alleged sources were probably false. In 1793, Bashō was "godified" by the Shinto bureaucracy, and for a time any criticism of his poetry was considered blasphemy.

At the end of the XIX century, this period of unanimous passion for Bashō's poems came to an end. Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902), possibly Bashō's most famous critic, overthrew the long period of orthodoxy by raising objections to Bashō's style. Shiki, however, also helped Bashō's poetry reach the leading intellectuals of the day and the Japanese public in general. He invented the term haiku, which replaced that of hokku, to refer to the freestanding form with a 5-7-5 structure, which he considered the most convenient and artistic form. all the haikai no renga. Of Bashō's work he went so far as to say that "eighty percent of his production is mediocre".

On this issue, Jaime Lorente maintains in his research paper "Bashō and the 5-7-5 metro" that, of the 1012 hokkus analyzed by master Bashō, 145 cannot be classified in the 5-7-5 meter, since they are broken meter (specifically, they present a greater number of blackberries [syllables]). In percentage they represent 15% of the total. Even establishing 50 poems that, presenting this 5-7-5 pattern, could be framed in another structure (due to the placement of the particle "ya") the figure is similar. Therefore, Lorente concludes that the teacher was close to the traditional pattern.

Critical review of Bashō's poems continued into the 20th century, with notable works by Yamamoto Kenkichi, Imoto Nōichi, and Tsutomu Ogata. The 20th century also saw Bashō's poems translated into various languages and published around the world. Considered the haiku poet par excellence, he managed to be a benchmark, also due to the fact that haiku came to be preferred to other more traditional forms such as the tanka. or renga. Bashō has been considered the archetype of Japanese poets and poetry. His concise, impressionistic view of nature influenced Ezra Pound and the Imagists in particular, and later the poets of the Beat generation as well. Claude-Max Lochu, on his second visit to Japan, he created his own 'travel painting', inspired by Bashō's use of travel for inspiration. Musicians such as Robbie Basho and Steffen Basho-Junghans were also influenced by him. In Spanish, José Juan Tablada is worth noting. In Catalonia there are examples of the use of haiku by Carles Riba and in Mallorca by Llorenç Vidal.

List of works

- "Kaio" (1672)

- "Minashiguri" (1683)

- "Nozarashi Kiko" "Remembers of a journey of a demaculate sack of bones") (1684)

- "Fuyu no Hi" (1684)

- "Haru no Hi" (1686)

- "Kashima Kiko" (1687)

- "Oi no Kobumi," or "Utatsu Kiko" (1687)

- "Kiko Sarashina" (1688)

- "Arano" (1689)

- "Hisago" (1689)

- "Sarumino" (1691)

- "Saga Nikki" (1691)

- "Basho no Utsusu kotoba" (1691)

- "Heiko no Setsu" (1692)

- "Sumidawara" (1694)

- "Betsuzashiki" (1694)

- "Oku no Hosomichi" (1694)

- "Zoku Sarumino" (1698)

Referenced bibliography

- Pagès, J.; Santaeulàlia, J.N. Marea low. Haikus of spring and summer. Barcelona: Edicions de la Magrana, 1986. ISBN 84-7517-176-1.

- Heads Garcia, Antonio. Path to deeplands (Senda de Oku), Matsuo Basho. Madrid: Hiperion, 1993. ISBN 978-84-7517-390-0.

- From the Source, Ricardo. “Introduction”, Fifty Haikus. Madrid: Hiperion, 1997. ISBN 84-8264-011-9.

- Heads Garcia, Antonio. Immortal Jaikus. Madrid: Hiperion, 1983. ISBN 84-7517-109-5.

- Carter, Steven. «On a Bare Branch: Bashō and the Haikai Profession». Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 117, 1, p. 57-69.

- Lawlor, William. Beat Culture: Lifestyles, Icons, and Impact. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2005. ISBN 978-1-85109-405-9.

- Lorente, Jaime. Bashō and 5-7-5 subway. Toledo: sabi-shiori, 2023 (2nd edition). ISBN 979-8602733846

- (Kenzō Okamura) says (Bashō to Yute-ni). Åsaka:会 Русский (Basho Haiku Kai), 1956.

- Shirane, Haruo. Traces of Dreams: Landscape, Cultural Memory, and the Poetry of Basho. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8047-3099-7.

- Ueda, Makoto. The Master Haiku Poet, Matsuo Bashō. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1982. ISBN 0-87011-553-7.

- Ueda, Makoto. Matsuo Basho. Tokyo: Twayne Publishers, 1970.

- Ueda, Makoto. Bashō and His Interpreters: Selected Hokku with Commentary. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8047-1916-0.

- Takarai, Kikaku (2006). An Account of Our Master Basho's Last Days, Translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa in Springtime in Edo. Hiroshima, Keisuisha. ISBN 4-87440-920-2

- Kokusai Bunka Shinkōkai (Colombian Federation) Introduction to Classic Japanese Literature. Tokyo: Kokusai Bunka Shinkōkai, 1948.

- Matsuo, Bashō (1966). "The narrow road to the Deep North", translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa. Harmondsworth, Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044185-9

- Matsuo, Bashō (2014). By paths of mountains. Selection, translation and notes by Fernando Rodríguez-Izquierdo and Gavala. Gijón, Satori. ISBN 978-84-940164-7-9

- Matsuo, Bashō (2015). Daily travel. Castilian version of Alberto Silva and Masateru Ito. Mexico, FCE. ISBN 978-987-719-089-2

- Matsuo, Bashō (2016). Leve presence. Selection, translation and notes by Fernando Rodríguez-Izquierdo and Gavala. Gijón, Satori. ISBN 978-84-945781-2-0

- Matsuo, Bashō. (2014). On the way to Oku and other travel papers. Version of Jesus Aguado. Palma (Spain): The boatman. ISBN 978-84-9716-912-7

Contenido relacionado

Bruce Willis

The Rolling Stones

Spanish theater of the first half of the 20th century