Mary Wollstonecraft

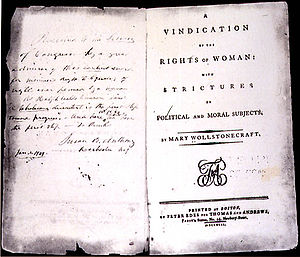

Mary Wollstonecraft /ˈwʊlstənkrɑːft/ (27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was an English writer and philosopher. She considered a leading figure of the modern world. She wrote novels, short stories, essays, treatises, a travelogue, and a book of children's literature. As a woman of the 18th century , she was able to establish herself as a professional freelance writer in London, unusual for the time. In her work A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), she argued that women are not by nature inferior to men, but appear to be so because they do not receive the same education, and that men and women should be treated as rational beings. She also imagines a social order based on reason. With this work, she established the foundations of liberal feminism and made her one of the most popular women in Europe at the time.

From both the general public and feminists, Wollstonecraft's life has been the subject of just as much, if not more, interest than her works, due to her unconventional and often tumultuous relationships. After two ill-fated romances with Henry Fuseli and Gilbert Imlay, Wollstonecraft married the philosopher William Godwin, one of the forerunners of the anarchist movement; she with him she had a daughter, Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein and wife of romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Wollstonecraft died at the age of thirty-eight from complications arising from the birth of her daughter, leaving behind several unfinished manuscripts.

After Wollstonecraft's death, her husband published a memoir of her life (1798), revealing her unorthodox lifestyle, inadvertently wrecking her reputation for more than a century. However, with the rise of the feminist movement leading up to the turn of the XX century, Wollstonecraft's advocacy of equality for women and her critiques of conventional femininity grew in importance. Today, she is considered one of the founding figures of feminist philosophy and is often cited by feminists as a major influence on both her life and her work.

Early Years

Wollstonecraft was born on April 27, 1759 in Spitalfields, London, England. Although her family had a decent income when she was growing up, her father squandered it on speculative ventures. As a result, the family became financially unstable and were forced to move frequently during Wollstonecraft's youth. This financial situation became so dire that Mary's father forced her to spend an inheritance that she otherwise he would have received in his maturity. In addition, it seems that he was a violent man who mistreated his wife when he was drunk. As a teenager, Wollstonecraft used to lie to protect her mother from her, and with her sisters, Everina and Eliza, she played an equally influential role. For example, at one point in 1784, she convinced her sister Eliza, who had suffered from what was probably postpartum depression, to abandon her husband and her baby; Wollstonecraft arranged for Eliza to run away, thus demonstrating her willingness to defy social norms. The price she had to pay, however, was high: her sister suffered social rejection and, since she could not remarry, she was banished to a life of poverty and hard work.

Wollstonecraft had two friendships in her youth, the first with Jane Arden in Beverley. The two often read books together and attended classes taught by Arden's father, a self-styled scientist and philosopher. Wollstonecraft greatly enjoyed the intellectual atmosphere of the Arden household and highly valued her friendship with the girl, sometimes to the point of being emotionally possessive. Wollstonecraft wrote to him "Certain romantic notions of friendship have formed in me... I am a little peculiar in my understanding of love and friendship; I have to have first place or none.” Some of Wollstonecraft's letters to Arden reveal the volatile and particularly depressive emotions that plagued her throughout her life.

The second, and possibly more important, friendship was with Fanny Blood, whom Wollstonecraft credited with opening her mind. Wollstonecraft imagined a utopia of coexistence with Blood; They made plans to rent rooms together and support each other emotionally and financially, but this dream was dashed by the reality of her financial problems. Furthermore, Wollstonecraft realized that she had idealized Blood, she was more in favor of the values traditionally considered feminine than Wollstonecraft herself. Regardless, Mary remained devoted to her and her family throughout her life (she frequently offered some money to her brother, for example). In order to earn a living, Wollstonecraft, her sisters, and Blood opened a school in Newington Green, a nonconformist community, but Blood soon became engaged to a man. After her wedding, her husband, Hugh Skeys, took her to Europe with the intention of improving her health, which had always been poor, but after becoming pregnant, Blood's health declined. deteriorated further. In 1785, Wollstonecraft went to Lisbon with Blood to care for her, but to no avail, Blood died in childbirth on November 29 of that year; furthermore, her abandonment of the school caused the project to fail. Blood's death shattered Wollstonecraft and was part of the inspiration for her first novel.

“The first of a new genre”

After Blood's death, Wollstonecraft returned to Britain, where she began working as a governess for the respectable Kingsborough family in Ireland. Although she could not get along with Lady Kingsborough, to the children she was a stimulating instructor; Margaret King later said that she "had freed her mind of all superstition". Some of Wollstonecraft's experiences during those years would be reflected in her only book of children's literature, Original Stories from Life. royal (1788).

Frustrated by the limited employment options available to respectable but poor women—a barrier Wollstonecraft eloquently describes in the chapter Reflections on the Education of Daughters (1787) titled Unfortunate Situation of Females, Fashionably Educated, and Left Without a Fortune, whose possible translation would be "unfortunate situation of modernly educated women who have been left without fortune"— decided, after exercising a year as a governess, embark on a career as an author. This was a radical decision, since, in those days, few women could survive as writers. When she wrote to her sister Everina in 1787, she was trying, in her own words, to become "the first of a new genre". She moved to London and, aided by the liberal publisher Joseph Johnson, established a home in which to live and began a job that supported her. She learned French and German and translated texts, including On the Importance of Religious Opinions by Jacques Necker and Elements of Morality for dealing with children by Christian Gotthilf Salzmann. She also wrote reviews, primarily of novels, for Johnson's Analytical Review. Wollstonecraft's intellectual universe was expanded during this time thanks to the reading that she carried out for her reviews and also by the companies that she frequented, Wollstonecraft attended the renowned Johnson dinners and met intellectuals such as Thomas Paine and William Godwin.

While in London, Wollstonecraft had a relationship with the artist Henry Fuseli, despite the fact that he was married. She was, she wrote, captivated by his genius, "the greatness of his soul, the quickness of his comprehension, and his charming charm." He proposed a utopian arrangement of joint living with Fuseli and his wife, but refused. Fuseli's wife was horrified and Fuseli broke off his relationship with Wollstonecraft. After Fuseli's rejection, Wollstonecraft decided to travel to France to escape the humiliation of the incident and to participate in the revolutionary events he had recently celebrated in his Avindication of the rights of man (1790). She wrote this work in response to Edmund Burke's conservative criticism of the French Revolution in Reflections on the French Revolution (1790). She took aim at these same ideas more indirectly in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), her best-known and most influential work.

France and Gilbert Imlay

Wollstonecraft marched on Paris in December 1792, arriving about a month before Louis XVI was guillotined. The country was in turmoil. She sought out other British visitors such as Helen Maria Williams and joined the city's expatriate circle. Having just written A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, she was determined to put her ideas into practice, and in the intellectually stimulating atmosphere of the French Revolution had her most experimental love affair: she met and fell hopelessly in love with Gilbert Imlay, an American adventurer. Whether or not Wollstonecraft was interested in a marriage, Imlay was not, and she seemed to have fallen in love with him. an idealization of this man. Although Wollstonecraft had rejected the sexual component of relationships in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Imlay aroused her passion and interest in sex. Wollstonecraft soon became pregnant, and on 14 May 1794 she gave birth to her first daughter, Fanny, whom she named after what may have been her best friend. Despite all the turmoil surrounding her, Wollstonecraft never stopped writing; while she was in France, she collected information for her historical version of the early years of the Revolution and wrote avidly at Le Havre. In December 1794 she was published in London A Historical and Moral View of the Origin of the French Revolution.

The political situation worsened, Great Britain declared war on France, placing British citizens established in France in considerable danger. To protect Wollstonecraft, Imlay registered her as her wife in 1793, even though they were not married.Some of Wollstonecraft's friends were not so lucky; many of them, like Thomas Paine, were arrested and some were even guillotined. Later, after leaving France, Wollstonecraft would continue to refer to herself as Mrs. Imlay, even to her sisters, in order to grant her daughter legitimacy.

Imlay, unhappy with the motherly homely Wollstonecraft, left her. He promised that he would return to Le Havre, France, where she had gone to give birth, but his delays in writing and her long absences convinced Wollstonecraft that he had found another woman. Her letters to him are filled with desperate protests, seen by many critics as expressions of a deeply depressed woman, according to some as a result of her circumstances, alone with a daughter in the midst of a revolution.

England and William Godwin

Wollstonecraft returned to London in April 1795 to seek Imlay, but he turned her down. In May 1795 she tried to commit suicide, probably with laudanum, but was saved by Imlay (although how is not entirely clear). In a last-ditch attempt to win him back, she embarked on some business related to him in Scandinavia, trying to recover some of his losses. Wollstonecraft undertook this arduous journey with her little daughter and a maid of hers. He recounted the events and his thoughts in letters to Imlay, many of which were later published as Letters Written During a Brief Stay in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark in 1796. Wollstonecraft considered his suicide deeply rational and wrote after his rescue: «I have only to regret that, when the bitterness of death had passed, I was inhumanly brought back to life and misery. But I have the firm determination that this disappointment does not disconcert me; I will not let what was one of the calmest acts of my reason remain as a desperate attempt. As far as that is concerned, I only have myself to answer to. If I cared about what they call reputation, it would be other circumstances that would dishonor me."

Little by little, Wollstonecraft returned to her literary life, associating with Joseph Johnson's circle again, particularly Mary Hays, Elizabeth Inchbald, and Sarah Siddons through William Godwin. Godwin and Wollstonecraft's courtship began slowly, but eventually developed into a passionate relationship. Godwin had read her Letters written in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark and later wrote that "If ever there was a book made for the reader to fall in love with its author, for me it is this. She speaks of her pain in a way that fills you with melancholy and melts you in tenderness, at the same time that she demonstrates a genius that inspires great admiration ».Once Wollstonecraft became pregnant, they decided to marry so that her child was legit. Their wedding exposed the fact that Wollstonecraft had never been married to Imlay, and she and Godwin lost many friends as a result. Godwin received criticism because he had advocated the abolition of marriage in his treatise Inquiry into Political Justice. After the wedding, which took place on 29 March 1797, they moved into two terraced houses, known as like El Polígono, so that they could preserve their independence; they often communicated by letter. They were reportedly happy and had a stable, if tragically brief, relationship.

Death and Memoirs of Godwin

On August 30, 1797, Wollstonecraft gave birth to their second daughter, Mary. Although the delivery seemed to go well at first, the placenta ruptured and became infected during birth, not uncommon in the 18th century. After several days of agony, Wollstonecraft died of sepsis on 10 September. Godwin was devastated; he wrote to her friend Thomas Holcroft: & # 34; I firmly believe that there is no one in the world who can compare to her. I know from experience that we were made to make each other happy. I absolutely do not expect to ever be happy again." She was buried in St Pancras Old Church and a memorial was built there, although both her and Godwin's remains were later moved to Bournemouth. you can read, "Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: Born April 27, 1759: Died September 10, 1797."

In January 1798 Godwin published his Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Although Godwin felt that he was describing his wife with love, compassion and sincerity, many readers were shocked by his revealing the illegitimacy of Wollstonecraft's first child, their love affairs and her suicide attempts. Robert Southey accused him to uncover all the secrets of his deceased wife. Godwin's Memoirs portrayed Wollstonecraft as a woman deeply committed to her feelings, balanced, and more skeptical of religion than her own writings suggest.

Legacy

Wollstonecraft has had what Cora Kaplan calls a "curious" legacy: "for an activist author fond of many genres, Wollstonecraft's life has been followed much more closely over the last quarter-century than her writings." After the devastating effect of the Memoirs Wollstonecraft's reputation did not enjoy very good health for a century; she was even criticized by authors such as Maria Edgeworth, who clearly created the eccentric Harriet Freke from Belinda (1801) in the image and likeness of Wollstonecraft. It was not until the end of the XIX century that the writer was applauded again. With the advent of the women's movement, women with as different political views as Virginia Woolf and Emma Goldman recaptured Wollstonecraft's story and celebrated the "experiments of a lifetime," as Woolf called them in a famous essay. Many In any case, they continued to despise the Wollstonecraft way of life.

Thus, the feminism of the 60s and 70s brought success again to the works of Wollstonecraft. Her good moment reflected the one that the feminist movement also enjoyed; for example, in the early 1970s six biographies of Wollstonecraft were published presenting her passionate life as well as her radicalism and rationality. Wollstonecraft was seen as a paradoxical and intriguing figure who did not subscribe to the 1970s version of feminism. In the 1980s and 1990s, a different image of the writer appeared, describing her much more as a creation of her time; intellectuals such as Claudia Johnson, Gary Kelly and Virginia Sapiro showed the continuation between Wollstonecraft's thought and other important ideas of the 18th century, such as sensibility, economics and political theory.

MAIN WORKS

Reflections on the education of daughters (1787) and original stories (1788)

The first two works of Wollstonecraft addresses the issue of education. The first one, reflections on the education of the daughters, is a behavior guide, a text that advises not only about moral issues such as benevolence, but also about those related to the label, like dressing. This type of writings was extremely popular during the century xviii , particularly among the emerging middle class, which saw in them the way of developing customs in the middle class that challenged the code of aristocratic behavior. Although much of those writings are not very original, some fragments, such as the Wollstonecraft description of the suffering of the single woman They point out that the writer was not simply content to imitate other authors.

Vindication of the rights of man (1790)

in 1790 Edmund Burke published reflections on the French revolution . Burke, who had supported the war of independence of the United States, surprised his contemporaries arguing against the French revolutionaries. His book resulted in what is now known as the " Revolution Controversy " (which could be translated as " controversy of the revolution "), a war brochure that responded to Burke's text.

La Vindication of human rights of Wollstonecraft was the first of many other seminal works in this war, such as The rights of men Thomas Paine. But Wollstonecraft wasn't just answering the Reflections of Burke, but also his Philosophical inquiry into the origin of our ideas about the sublime and the beautiful (1756), in which the writer argued that beauty is associated with weakness and femininity and that the sublime is associated with strength and masculinity. Wollstonecraft turns Burke's rhetoric around Reflections, turning it against him; he argues that his theatrical staging, like the one that makes in his well-known and adorned description of the horrors that Marie Antoinette had to suffer, turns Burke's readers—the citizens— into weak women who are convinced by the show. He also criticizes Burke's classic argumentation, demonstrating, like many other critics, that he is moved by the suffering of Marie Antoinette but not by the pressing situation of poor and starving women in France; in fact, he despises these openly. Wollstonecraft also challenges Burke's assertion that tradition must sustain political theory; it defends rationality, noting that Burke's system would logically lead to the continuation of slavery by the simple fact of being an ancestral tradition. Wollstonecraft does not reject the need for compassion in the human relations that Burke emphasizes, but often argues that this compassion is insufficient for social cohesion and at some point writes: "A similar misery asks for more than tears—I stop to remind myself—we must always analyze any situation rationally." Significantly, it ends Vindication of human rights with a reference to the Bible: "He fears God and loves the creatures that belong to him. Behold the duty of man to the full!"

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)

A Vindication of Women's Rights is a blend of literary genres—a political treatise, a behavior guide, and an educational treatise. In order to discuss the position of women in society, Wollstonecraft outlines the connections between four terms: right, reason, virtue, and duty. Rights and duties are completely linked for Wollstonecraft—if you have civic rights you also have civic duties. As she briefly comments "without rights there can be no obligation"

One of Wollstonecraft's main arguments in A Vindication of the Rights of Women is that women should be educated rationally, so that they can thus contribute to society. Wollstonecraft thus scathingly answers writers such as James Fordyce and John Gregory and educational philosophers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who argues that women do not need rational education. (Rousseau, as he is well known, argued in Emile (1762) that women should be educated for pleasure.) Wollstonecraft, on the contrary, maintains that wives should be the rational companions of their husbands. He points out that if a society decides to leave the education of its children to women, they must be well educated in order to pass the knowledge on to the next generation. Wollstonecraft declares that women are stupid and superficial (calling them, for example, &# 34;spaniels" or "toys" at a certain point), but says it is not due to an inborn deficiency but rather because men have denied them access to education. Wollstonecraft is determined to illustrate the limitations that a lack of education has placed on women; poetically, he writes: "Taught from childhood that beauty is the scepter of women, the mind molds itself to the body and, wandering in its gilded cage, seeks only to adorn its prison." The implication of this statement is that, without Despite the ideological damage that encourages young girls from an early age to focus their attention on beauty and outward enhancements, women could achieve much more.

The extent to which Wollstonecraft believed in the equality of women and men can be debated; she was certainly not a feminist in the modern sense of the word (the words feminist and feminism did not exist until after 1890), since she did not ask for equal rights (for example he did not call for the right to suffrage for women) in his writings. He declares that men and women are equal in the sight of God and that they are subject to the same moral laws. In any case, the calls for equality are in contrast to his statements about the superiority of masculine strength and courage. Wollstonecraft maintains, in the well-known and ambiguous phrase: "Do not conclude that I want to reverse the order of things; I have already asserted that, by their constitution, men seem designed by Providence to achieve a greater degree of virtue. I speak referring to this sex in general; but I see no reason to conclude that their virtues should differ because of their nature. In fact, how could it be if virtue is an eternal constant? I must, therefore, if I reason consistently, hold as strongly that they follow that same end as I hold that God exists."

One of Wollstonecraft's most scathing criticisms in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman is the one she makes against false and excessive sensitivity, particularly in women. She argues that women who succumb to sensitivity are "moved by any momentary gust or feeling" and because they are "prised by their senses" are unable to think rationally. And so, she declares, they harm not only themselves but others. all of civilization: these are not women who can help perfect civilization — a popular idea in the 18th century — but women who collaborate in its destruction. Wollstonecraft is not advocating that reason and feeling should act independently; she thinks they should serve each other.

In addition to her more general philosophical arguments, Wollstonecraft outlines a specific educational plan. In Chapter 12, "On National Education," she argues that all children should be sent to a "national boarding school." at the same time that they are given a certain education at home that "encourages a love of home and homely pleasures." She also maintains that this schooling should be mixed, since men and women, whose marriages are the foundation of society, should be "educated according to the same model."

Wollstonecraft directs her text at the middle class, which she calls "the most natural state," and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman is steeped in the bourgeois vision of world. He defends modesty and diligence and attacks wealth using the same language with which he accuses women of lack of usefulness. Anyway, she is not a staunch friend of poverty; for example, in her national education plan she suggests that, after the age of nine, the poor should be separated from the rich and taught in another school.

Mary (1788) and Maria (1798)

Both are novels by Wollstonecraft focusing on the desperate plight of some women in the 18th century. In the first of them, Mary: A Fiction (in Spanish María's novel ), the protagonist of the same name, who was ignored in her childhood, suddenly becomes an heiress; consequently her family arranges for her a convenient marriage with a man she doesn't even know. Mary's husband, Charles, quickly disappears in the novel and the story focuses on the relationship between Mary and her ailing friend, Ann. They travel through Europe together hoping to improve Ann's health, but to no avail; Ann dies. During that time, Mary meets and falls in love with Henry. After Ann's death, Mary and Henry return to England. Henry is also sick, but Mary chooses to live with him and her mother for her remaining weeks. Mary never recovers from the loss of Ann and Henry and when her husband reappears at the end of the book she cannot bear to be in the same room with him. The ending of the book suggests that she will die young. Like María, this book is a reflection on marriage. There is no successful marriage in the novel and at the end, as she is dying, Mary "thinks she is getting closer to that world where there is no marriage and being given in marriage", presumably as a positive part of your situation. The only satisfying relationships in the book are friendships, and even these end tragically for Mary.

Mary is an unfinished novel often considered Wollstonecraft's most radical work. In it she details many of the "injustices suffered by women", not only from one point individual but also general view. The protagonist, María, is locked up in an asylum by her spendthrift husband in order to steal her money; sadly, her daughter is also taken from her. While in the asylum, Maria meets and perhaps falls in love with a man named Darnford, but since the tale is unfinished, it is unclear whether Wollstonecraft intended to happily resolve the sentimental plot or end the novel tragically. Maria also befriends one of the nurses, Jemima, who, like Maria herself, has a horrifying story to tell about her married life. Jemima's tale gives Wollstonecraft the opportunity to show the bonds between women of different classes. Significantly, it is one of the first moments in the history of feminism in which an argument related to social classes is advanced, which affirms that women of different economic positions have the same interests in the fact that they are women. Deeply affected by Through her own love affairs and experiences in France, Wollstonecraft changed some of her previous views about classes; she would not have made those same claims six years earlier, when she described the middle class as "the natural state."

Letters written in Sweden, Norway and Denmark (1796)

Letters Written in Sweden is a travelogue, but a very particular one; it consists not only of Wollstonecraft's reflections on Scandinavia and its people but also on her relationship with Imlay (although she is not mentioned by name). In this, her last major finished work, Wollstonecraft is strongly influenced by the themes Rousseau treats in Reveries of the Solitary Stroller (1782): "the search for the source of human happiness, the stoic rejection of material goods, the ecstatic embrace of nature, and the essential role of feeling in understanding." While Rousseau ultimately rejects society, Wollstonecraft celebrates the national landscape and industrial progress in her texts. Wollstonecraft also explores the connections between the sublime and sensibility. Many of the letters describe the stunning landscape of Scandinavia and Wollstonecraft's desire to create an emotional connection to that natural world. In this way, she leaves a greater role to the imagination than she had previously done in her own works. The writer compares this imaginative connection to the world with a commercial and mercenary attitude that she associates with Imlay and that she criticizes through her writing.

Works

- Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787), translated into Spanish as Reflections on the education of daughters.

- Mary: A Fiction (1788), translated into Spanish as The novel by Mary.

- Original Stories from Real Life (1788), translated into Spanish as Original Real Life Stories.

- Of the Importance of Religious Opinions (1788) (translation).

- The Female Reader (1789) (anthology).

- Young Grandison (1790) (translation).

- Elements of Morality (1790) (translation).

- A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790), translated into Spanish as Vindication of human rights.

- A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), translated into Spanish as Vindication of women ' s rights.

- An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution (1794).

- Letters Written during a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark (1796).

- Contributions Analytical Review (1788-1797) (posthumous publication).

- The Cave of Fancy (1798, posthumous publication; fragment).

- Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman (1798, posthumous publication; unfinished).

- Letters to Imlay (1798, posthumous publication).

- Letters on the Management of Infants (1798, posthumous publication; unfinished).

- Lessons (1798, posthumous publication; unfinished).

- On Poetry and our Relish for the Beauties of Nature (1798, posthumous publication).

Tributes

In Spain, the writer Fernando Marías Amondo and the artistic collective he founded, called Hijos de Mary Shelley, organized a show in honor of Mary Wollstonecraft and also published a book entitled Wollstonecraft. Daughters of the Horizon in which important writers such as Cristina Fallarás, Espido Freire, Paloma Pedrero, Nuria Varela, Cristina Cerrada, Eva Díaz Riobello, María Zaragoza, Raquel Lanseros and Vanessa Montfort participated.

Contenido relacionado

Ideal (philosophy)

Lee Marvin

Henri Leon Lebesgue