Mary Miller

María Juana Moliner Ruiz (Paniza, Zaragoza, March 30, 1900-Madrid, January 22, 1981) was a Spanish librarian, archivist, philologist and lexicographer, author of Dictionary of use of Spanish.

Biography

Family and early years

He was born on March 30, 1900 in the Zaragoza town of Paniza. Her parents were the rural doctor Enrique Moliner Sanz (1860-1923) and Matilde Ruiz Lanaja (1872-1932), she being the middle of three siblings, between Enrique (August 15, 1897) and Matilde (July 7, 1904).

In 1902, according to their own testimony, the parents and both older children moved to Almazán (Soria) and, almost immediately, to Madrid. The youngest daughter, Matilde, was born in the capital. In Madrid, the brothers attended, intermittently, the Institución Libre de Enseñanza school on Calle del Obelisco, later called Martínez Campos, and they took their own exams at the Cardenal Cisneros Institute. As he recalled years later in a couple of interviews and told Carmen Castro, at the Institution he received classes from Américo Castro, which aroused his interest in grammar.

Years of difficulty and training

His father, who had obtained a medical position in the navy, after a second trip to America in 1912, stayed in Argentina, abandoning the family, although in the early days he continued to send money. This probably motivated the mother to decide in 1915 to leave Madrid and return to Aragón, where she had some land and family support. There the family got ahead largely thanks to the financial help of María, who, even when she was very young, He dedicated himself to giving private classes in Latin, mathematics and history. According to what her children later said, these harsh circumstances were fundamental in the development of her mother's personality.

She took her first baccalaureate exams, as a free student, at the Cardenal Cisneros General and Technical Institute in Madrid (between 1910 and 1915), passing in July 1915 to the Goya Institute, then General and Technical Institute of Zaragoza, of the who was an official student from 1917 and where she finished high school in 1918.

First steps as a philologist and archivist

In Zaragoza she trained and worked as a philologist and lexicographer at the Aragon Philology Study, directed by Juan Moneva from 1917 to 1921, years in which she collaborated in the production of the Aragonese Dictionary of said institution. As has been highlighted, the work method acquired and practiced in this institution must have been very important in her philological training and in her later work as a lexicographer.

He graduated in 1921 specializing in History, the only one existing at that time in the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters of the University of Zaragoza, with the highest marks and Extraordinary Award. Almost the same steps were followed by her sister Matilde Moliner, who graduated in the same discipline with the same honors, but in 1925 and was also a cooperator at the Aragon Philology Study.

Career as an archivist and librarian

The following year he won the opposition for the Facultative Corps of Archivists, Librarians and Archaeologists, beginning his internship at the National Library of Spain, being assigned in August to the General Archive of Simancas, from which he passed, in 1924, to the Archive of the Delegation of the Treasury in Murcia, and years later, at the beginning of the thirties, that of Valencia.

In Murcia she met Fernando Ramón Ferrando, nine years her senior, who had won the chair of General Physics in 1918 and was a renowned professor in the Murcian capital. They were married in the parish church of Santa María de Sagunto on August 5, 1925. Her first daughter died.In Murcia their sons Enrique (medical researcher in Canada, who died in 1999) and Fernando, an architect, were born. After the family moved to Valencia, the two youngest children were born: Carmen (philologist) and Pedro (industrial engineer, director of the ETSI of Barcelona, who died in 1985). She was also the first woman to teach at the University of Murcia, during 1924. In the decade 1929-1939 he took an active part in the national library policy, collaborating with the Institución Libre de Enseñanza in projects such as the Pedagogical Missions.

Her inclination for the archive, for the organization of libraries and for cultural diffusion, led her to reflect on it in several texts (Rural libraries and library networks in Spain, 1935) and to a very active participation in the work group that published, collectively, the Instructions for the service of small libraries (1937), a work linked to the aforementioned Pedagogical Missions projected and launched by the Second Spanish Republic. The program to provide each town in Spain with a small library managed to open more than 5,500.

In addition, he directed the Library of the University of Valencia, participated in the Book Acquisition and International Exchange Board, which was in charge of making the books that were published in Spain known to the world, and carried out extensive work as a member of the Library Section of the Central Council of Archives, Libraries and Artistic Treasure, created in February 1937, in which she was in charge of the School Libraries Subsection; from there, in 1938, she designed the Organization Plan project General of State Libraries.

In 1939, after the Spanish Civil War had ended and the Second Spanish Republic had disappeared, the couple suffered Franco's purge of the Spanish teaching profession: he lost his chair and was transferred to Murcia, and María returned to the Valencia Treasury Archive, lowering eighteen levels in the ranks of the Corps. However, in 1946 her husband was rehabilitated, becoming a professor of Physics at the University of Salamanca.

Before 1936, he had studied German. After 1939, she studied English at the British consulate in Valencia, her teacher being the wife of the writer Walter Starky.

The family settled in Madrid and María joined the Library of the Superior Technical School of Industrial Engineers of Madrid, becoming its director until her retirement in 1970. That year, the Ministry of Education and Science, by order of July 6, 1970, agreed to his entry into the Civil Order of Alfonso X the Wise, in his category of Lazo.

Last years

The last years of her life were marked by the care of her husband, who retired in 1962, sick and blind by 1968, and by the desire to quietly polish and expand his Dictionary of Spanish use which had been published in two large volumes in 1966-1967. However, in the summer of 1973 the first symptoms of cerebral arteriosclerosis suddenly appeared, a disease that gradually withdrew her from all intellectual activity. Her husband died on September 4, 1974. In 1970 she left her house on Don Quijote street (Cuatro Caminos neighborhood) and moved to Moguer street (Ciudad Universitaria neighborhood), where she died in 1981; a plaque memorial marks the building where he spent those last years.

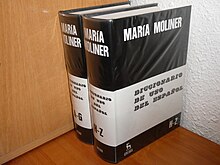

Dictionary of Spanish Use (DUE)

Around 1952 his son Fernando brought him from Paris the Learner’s Dictionary of Current English by A. S. Hornby (1948). To her, who, aware of the deficiencies of the DRAE, was already making notes on words, this book gave her the idea of making "a small dictionary... in two years." At that time, she began to compose her Dictionary of Spanish use , an ambitious undertaking that would take her more than fifteen years, always working in her house. At the request of the academic Dámaso Alonso, who followed his work with interest and had connections with the Gredos publishing house, Moliner ended up signing, in 1955, a contract with it for the future publication of the work, whose typographical edition was very laborious. For fifteen She wrote it at her living room table outside of her five-hour work shift as a librarian using index cards, a Mont Blanc pen, and an Olivetti Pen 22 typewriter.

His Dictionary was of definitions, synonyms, expressions, set phrases and word families. In addition, he anticipated the arrangement of the Ll in the L, and from Ch to C (a criterion that the RAE did not follow until 1994), or terms in common use but that the Royal Academy Spanish had not admitted, such as "cybernetics", and added a grammar and syntax with numerous examples. As she once stated, «The dictionary of the Academy is the dictionary of authority. In mine, authority has not been taken into account too much»... «If I start to think about what my dictionary is, something presumptuous assails me: it is a unique dictionary in the world».

The first (and the only original edition authorized by her) was published in 1966-1967.

In 1998, a second edition consisting of two volumes and one CD-ROM was published, as well as an abridged one-volume edition. The third and last revision was published in September 2007, in two volumes.

As Nobel Prize winner for Literature Gabriel García Márquez put it:

Mary Moliner — to put it in the shortest way — made a prowess with very few precedents: she wrote alone, in her house, with her own hand, the most complete, most useful, more aquecious and more fun dictionary of the Castilian language. His name is Dictionary of Spanish use, It has two tomes of nearly 3000 pages in total, weighing three kilos, and it comes to be, therefore, more than two times longer than that of the Royal Academy of Language, and — in my opinion — more than two times better. Maria Moliner wrote it in the hours that left her employment as a librarian free.Gabriel García Márquez

Relationship with the Royal Spanish Academy

On November 7, 1972, the writer Daniel Sueiro interviewed her in the Heraldo de Aragón. The headline was a question mark: "Will María Moliner be the first woman to enter the Academy?" She had been proposed by Dámaso Alonso, Rafael Lapesa and Pedro Laín Entralgo. But the chosen one, in the end, was Emilio Alarcos Llorach. Among the possible reasons for not accepting it, the fact that she is not a trained philologist, her condition as a woman, or even that her dictionary did not include profanity have been pointed out.She commented on the subject as follows:

Yeah, my biography is very spit about how my only merit is my dictionary. I mean, I don't have any work that can be added to that to make a long list that contributes to accrediting my entrance to the Academy [...] My work is clean the dictionary. [Later added:] Of course it is a point that a philologist [by Emilio Alarcos] enters the Academy and I already throw myself out, but if that dictionary had been written by a man, he would say: "But and that man how he is not at the Academy!Maria Moliner quoted by Daniel Sueiro

The proposals did not prosper and it was another woman, Carmen Conde, who took the chair. The process came to be glossed in one of her obituaries entitled "An academic without a chair."

Violeta Demonte, professor of Spanish Language at the Autonomous University of Madrid commented on Moliner's dictionary: «The attempt is important and novel. However, as the theoretical foundation, the criteria of his analysis are not always clear and his fundamental assumptions have an intuitive origin, the usefulness of his work is uneven ».

Her most recent biographer, Inmaculada de la Fuente, summarized the causes as follows:

Because he was an intruder, in a way. Because he studied history at the University of Zaragoza, but had run his life around the world of archives and libraries and was not considered a philosopher. At that time, it did influence the woman. A woman who puts herself into a dictionary, but not the dictionary she initially wanted to do, but a dictionary that also questioned that of the RAE. I think she was admired, but not valued.Immaculate Source

In June 1973, the Royal Spanish Academy unanimously awarded him the Lorenzo Nieto López prize "for his work in favor of the language". María Moliner rejected the award.

In 1981, Luis Permanyer wrote a critique of the attitude of most academics, and in 2021, for the 40th anniversary of Moliner's death, the director of the RAE, Santiago Muñoz Machado, stated:

I like it not to be academic when I well deserved it for the work he did, and I am happy to celebrate and recognize the enormous merits of his work. [Also added:] It is not the RAE to blame for a recalcitrant machismo that existed for a long time and that could have been palliated when Maria Moliner appeared.Santiago Muñoz Machado

Documentaries

- Maria Moliner. Having words. Written, directed and produced by Vicky Calavia in 2018. Javier Barreiro, Pilar Benítez, José Manuel Blecua, Lucía Camón, Antón Castro, Manuel Cebrián, Imaculada de la Fuente, Marco Dugnani, Aurora Egido, Inés Fernández-Ordóñez, Luisa Gutiérrez, Victor Juan, María Antonia Martín Zorraquino, Eva Puyó, Soledad Puértolas, Carmen Ramón Moliner, Carme

- Maria Moliner: the books. Within the programme Women in history TVE. With a duration of 27 minutes it was issued in 2004. Among others, his biographer María Antonia Martín Zorraquino, Pilar Faus (archivera), Alvar González (son of José Navarro Alcacer, co-founder of Cossío schools) and his daughter Carmen Ramón Moliner (filóloga). Carmen Bonet was the writer and director. Ana Vargas was an advisor.

Acknowledgments

- Various Institutes of Secondary Education (IES), Schools of Child and Primary Education (CEIP) and Libraries bear their name; likewise the work of Maria Moliner has been honored and remembered at different cultural events, streets, etc.

- The playwright Manuel Calzada Pérez wrote in 2012 a play on María Moliner, called The dictionarywhich has been carried to the tables with great success in Spain, Chile and Argentina, among other countries. The work was the winner of the 2014 National Dramatic Literature Award and the 2015-2016 ACE Award.

- On March 30, 2019, the Google search engine commemorated Maria Moliner on her 119th anniversary of birth with a Doodle.

- In July 2019, the National Library of Spain baptized the general reading room, "María Moliner".

- In February 2020, the Circle of Fine Arts baptized its new room on the fifth floor as "María Moliner".

- The General Maria Moliner Library of the University of Murcia receives this name in its honor.

- For the 40th anniversary of its death, the National Library of Spain organized an act of tribute to its work and contribution to culture.

Works by María Moliner

- MolinerMary, Dictionary of Spanish use, volume 1, Gredos, 1979, 1502 pp. ISBN 9788424913441.

- Moliner, Dictionary of Spanish use, volume 2, Gredos, 1979, 1585 pp. ISBN 9788424913489.

Contenido relacionado

Complex

Oath

Frans Hals