Marxism

| Fathers of Marxism |

|---|

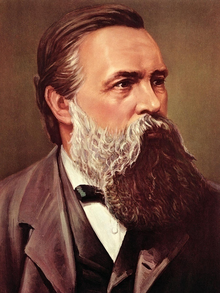

Marxism is a theoretical perspective and method of socioeconomic analysis and synthesis of reality and history, which considers class relations and social conflict using a materialist interpretation of historical development and adopts a dialectical vision of social transformation and a critical analysis of capitalism, composed mainly of the thought developed in the work of the German revolutionary philosopher, sociologist, economist and journalist of Jewish origin, Karl Marx, who contributed to sociology, economics, the law and history.

This group of philosophical, social, economic, political doctrines, etc. It acquired a more defined form after his death by a series of thinkers who complement and/or reinterpret this model, ranging from Friedrich Engels, Marx's companion and co-editor, to other thinkers such as Gueorgui Plekhanov, Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Rosa Luxemburg, Antonio Gramsci., Georg Lukács or Mao Zedong.

It is correct to speak of Marxism as a current of human thought. Marxism is mainly associated with the set of political and social movements that emerged during the XX century, among which the Russian Revolution stood out., the Chinese Revolution and the Cuban Revolution.

Marxism has sought to develop a unified social science (history, sociological theory, economic theory, political science and epistemology) for the understanding of societies divided into classes and the foundation of a revolutionary vision of social change that has inspired countless movements social and political in the world through modern history. It presents three identifiable dimensions: an economic-sociological dimension, a political dimension, and a critical-philosophical dimension expressed in the previous philosophy in Hegel's idealism and Feuerbach's materialism. The Marxist analysis, called historical materialism, emphasizes the determining character of of the material conditions - social relations and places in production - in people's lives and in the consciousness they have about themselves and about the world. Said material base is considered, in this perspective, ultimately determinant of other social phenomena, such as social and political relations, law, ideology or morality.

It has developed into many different branches and schools of thought, with the result that there is now no single definitive Marxist theory. Different Marxist schools place greater emphasis on certain aspects of classical Marxism while rejecting or modifying other aspects. Many schools of thought have tried to combine Marxist concepts and non-Marxist concepts, leading to conflicting conclusions.

Historical materialism and dialectical materialism remain the fundamental aspect of all Marxist schools of thought. This view is not accepted by some post-Marxists such as Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, who claim that history is determined not only by modes of production but also by consciousness and will. Several currents have also developed in academic Marxism, often under the influence of other points of view: structuralist Marxism, historical Marxism, phenomenological Marxism, analytical Marxism, humanist Marxism, Western Marxism and Hegelian Marxism. Marx's legacy has been contested among numerous trends, including Leninism, Marxism-Leninism, Trotskyism, Maoism, Luxemburgism, and libertarian Marxism.

Marxism has had a profound impact on the global academy and has influenced many fields such as archaeology, anthropology, science studies, political science, drama, history, sociology, art history and theory, political science, cultural studies, education, economics, ethics, criminology, geography, literary criticism, aesthetics, film theory, critical psychology and philosophy.

Introduction and summary

The central components of the Marxist explanatory theoretical model can be divided into four essential elements:

Firstly, the concept of «class struggle», which is formulated for the first time in the Communist Manifesto and which progressively transforms into the method of materialist analysis of human history as a result of material economic conditions, around the concepts of «social class», «contradiction» and «social division of labor» (historical materialism). In turn, Marxism follows the philosophical current where matter is the substrate of all reality, whether concrete or abstract (dialectical materialism). This method is at the same time based on the Hegelian logic commonly called «dialectic» (although in strictly Hegelian terms it is an «ontological logic», a model that at the same time surpasses the Hegelian concept of dialectic). Curiously, Marx did not specify in any particular work what the global limits of this method were, nor what was his concept of dialectic, however the prologue of the Critique of Political Economy is cited. > from 1859, as its most precise formulation.

The second central point of the Marxist theoretical model is the critique of the economy of capital, which is extensively developed in his work El capital, made up of three official volumes and a fourth volume edited separately. posthumously under the name of Theories on surplus value. In this work, based on a critique of the theories of the representatives of classical economics, Marx develops his labor theory of value, an alternative model to calculate the concept of "value" of the capitalist economy, based on the transformation of the " labor force" into a "commodity" and that the value of all merchandise is the "socially necessary labor time", distinguishing between "use value" and "exchange value", and reformulates it in his theory with which he deals de describes the exploitation of the proletariat by "capital". surplus value", legitimized in the rule of law through private ownership of the means of production and the free usufruct of those profits.

The third central point is the concept of «ideology», which is developed by Marx in his first books such as The German Ideology (co-authored with Engels) and which tries to explain the forms of mental domination of capitalist society and its relationship with its economic composition. This concept is abandoned for a few years by Marx to focus on political analysis. However, it reappears strongly in his book Capital, under the concept of "commodity fetishism", which would be a way of explaining a person's psychological inability to perceive the "value of use" of a commodity. This concept is extremely important, because it describes all the consequences of the forms of production of life within capitalism: the theory of value added, the idea that capitalism makes money by paying workers less than what they deserve and keep the rest as profit

The fourth central point of the Marxist theoretical model is the concept of «communism», a mode of production generated from the capitalist mode of production, which can exceed the limits of the capitalist society founded on human exploitation, on the extraction of value. Marx used the word many times, but never explained its scope and characteristics (except for some relatively short but lucid references, such as those that can be found in his Critique of the Gotha Program of 1875). A critical analysis of Marx's work would show that he would not have been willing to describe something that does not yet exist; therefore, the meaning of «communism» is found in a synthesis, both of the fundamental economic problems found explicitly in Capital and an analysis of the political-legal critique made by Marx of capitalist institutions.

Engels coined the term scientific socialism to differentiate Marxism from previous socialist currents encompassed by him under the term utopian socialism. The term Marxist socialism is also used to refer to the specific ideas and proposals of Marxism within the framework of socialism.

The proposed objective is that workers have access to the means of production in an institutionalized manner; that is to say, using the public institutions of the State so that the workers obtain means of production and avoid that «the bourgeoisie is concentrating more and more the means of production, the property and the population of the country. It brings together the population, centralizes the means of production (mainly, factories) and concentrates ownership in a few hands."

Marx proposes the abolition of private appropriation (a broader concept than property, which is merely legal) over the means of production, that is, “the abolition of the bourgeois property system”, as he mentions it in his Communist Manifesto: "What characterizes communism is not the abolition of property in general but the abolition of the bourgeois property system", since the bourgeoisie not only appropriates the social product through the law, but also corrupts institutions or other legal mechanisms to appropriate workers' property.

With access to the means of production by workers, Marxism concludes that a society without social classes will be achieved where everyone lives with dignity, without the accumulation of private property over the means of production for a few people, because it supposes that this is the origin and root of the division of society into social classes. This would imply enormous competition and efficiency in the economy; Furthermore, the worker could not exploit himself or another worker because both would have means of production. What such a scenario could cause is that workers organize to create larger companies through fair associations; For this reason, Marx expresses that «the average price of wage labor is the minimum possible. That is, the minimum necessary for the worker to remain alive. Everything that the salaried worker obtains with his work is, then, what he strictly needs to continue living and reproducing. We do not aspire in any way to impede the income generated through personal work, destined to acquire the necessary goods for life. And he emphasizes in his Manifesto : «We only aspire to destroy the ignominious character of bourgeois exploitation, in which the worker only lives to multiply capital». Thus, then, the worker or workers will be owners of their own businesses, starting a high trade; for this reason, in the Manifesto it specifies that "communism does not deprive anyone of the power to acquire goods and services".

Marx considers that each country has its particularities and, therefore, the measures to provide workers with means of production may be different, and that at first it will seem that they are not enough. Marx is clear about the law of scarcity and therefore the distribution of means of production in an institutionalized and legal way will take place little by little in a slow but effective transition; For this reason, he concludes in his Manifesto: «(...) by means of measures that, although at the moment they seem economically insufficient and unsustainable, in the course of the movement will be a great propelling spring, and which cannot be dispensed with, as a means of to transform the entire current production regime.”

In conclusion, Marx proposes the use of state institutions, such as the use of taxes to finance the purchase and distribution of the means of production to workers, which over time will form a perfectly competitive market.

Etymology

The term Marxism was coined by Karl Kautsky, who considered himself an orthodox Marxist during the dispute between Marx's orthodox and revisionist followers. Kautsky's revisionist rival Eduard Bernstein also later adopted use of the term. Engels did not endorse the use of the term Marxism to describe his or Marx's views. Engels claimed that the term was being misused as a rhetorical qualifier by those attempting to become true followers of Marx by while throwing others in different terms, such as those of Lassalle. In 1882, Engels claimed that Marx had criticized the self-proclaimed Marxist Paul Lafargue by saying that if Lafargue's views were considered Marxist, "one thing is certain." and I'm not a Marxist".

Intellectual influences of Marx and Engels

Marx had great philosophical influences, that of Feuerbach, who contributed and affirmed his materialist vision of history, and that of Hegel, based on Kantian philosophy and who inspired the young Hegelians, who among them, Marx used the dialectic in the application of materialism. Although for his doctoral dissertation he chose to compare the two great materialist philosophers of ancient Greece, Democritus and Epicurus, Marx had already endorsed the Hegelian method, his dialectic. Already in 1842 he had elaborated his Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right from a materialist point of view. But in the early 1840s, another great philosophical influence took effect on Marx, that of Feuerbach, especially with his work The Essence of Christianity. Both Marx and Engels embraced Feuerbach's materialist critique of the Hegelian system, albeit with some reservations. According to Marx, Feuerbach's materialism was inconsistent in some respects, which is why he calls it "contemplative." It is in the Theses on Feuerbach (Marx, 1845) and The German Ideology (Marx and Engels, 1846) where Marx and Engels settle their accounts with their philosophical influences and establish the premises for the materialist conception of history.

If in Hegel's idealism history was a process of continuous contradictions that expressed the self-development of the Absolute Idea, in Marx it is the development of the productive forces and the relations of production that determine the course of socio-development. historical. For the idealists, the engine of history was the development of ideas. Marx exposes the material basis of these ideas and finds the common thread of historical development.

Marx's review of Hegelianism was also influenced by Engels's 1845 book, The Condition of the Working Class in England, which led Marx to conceive of the historical dialectic in terms of conflict of classes and to see the modern working class as the most progressive force for revolution. Thereafter, Marx and Engels worked together for the rest of Marx's life so that the collected works of Marx and Engels were generally published together, almost as if it were the result of one person.

But the most significant part of the main guiding ideas, particularly in the economic and historical field, and in particular its clear and definitive formulation, correspond to Marx. What I brought—if it is excepted, all the more, two or three special branches—could have also contributed Marx without me. Instead, I would never have gotten what Marx achieved. Marx had more size, he saw farther, he attacked more and faster than all of us together. Marx was a genius; we, the others, at most, men of talent. Without him the theory would not be today, not with much, what it is. That's why he legitimately holds his name.Friedrich Engels (1886) Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of German Classical Philosophy - Part 4 (Engels footnote)

However, according to Isaiah Berlin, it was the works of Engels, rather than those of Marx, that were the main source of the historical and dialectical materialism of Plekhanov, Kautsky, Lenin, Stalin, Mao and even Trotsky.

In summary, Marx and Engels were based on the classical German philosophy of Hegel and Feuerbach; the British political economy of Adam Smith and David Ricardo; and French revolutionary theory, along with the French socialism of Rousseau, Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Babeuf, and Proudhon respectively, to develop a critique of society that was both scientific and revolutionary. Of these, according to Rudolf Rocker, Proudhon was —founder of mutualism— the socialist who would most inspire Marx. This critique reached its most systematic expression in the most important work dedicated to capitalist society, Capital: Critique of Political Economy.

The Hegelian analysis in his doctoral thesis on Epicurus's atomism was also highly influential in "synthesising the conception of alienation in praxis, associated with Hegel, and the materialist conception of the alienation of the human being from the nature found in Epicurus". Engels admits that it is in Epicurus's materialism that the basis for the development of a materialist dialectic lay, and not in the materialism of the French Enlightenment as Georgui Plekhanov thought. Marx also pointed out the importance of Aristotle in the labor theory of value, differentiating price from value and distinguishing between use value and exchange value. In Capital he concludes: “The brilliance of genius of Aristotle is demonstrated only by this, that he discovered, in the expression of the value of merchandise, a relation of equality. The peculiar conditions of the society in which he lived only prevented him from discovering what, 'truly', was at the bottom of this equality." In addition to the aforementioned roots, some Marxist thinkers of the XX, like Louis Althusser or Miguel Abensour, have pointed out in the work of Marx the development of themes present in the work of Machiavelli or Spinoza.

Another highly influential Greek philosopher was Heraclitus, considered one of the founders of dialectics. Hegel himself considered himself philosophically the heir of Heraclitus, to the point of stating: "There is no proposition of Heraclitus that I have not accepted in my Logic» (Hegel, Lectures on the history of philosophy). Engels, who was associated with the Young Hegelians, also gave Heraclitus credit for inventing dialectic, relevant to his own dialectical materialism, as Vladimir Lenin himself reaffirmed.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels also saw the new understanding of biology brought about by Charles Darwin's The Origin of Species and the understanding of evolution by natural selection as essential to the new understanding of socialism, since it provides a natural science basis for the historical class struggle. On the other hand, Engels turned to Lewis H. Morgan and his theory of social evolution in his work The Origin of the Family, private property and the state. Alexander Vucinich states that "Engels gave Marx credit for extending Darwin's theory to the study of internal dynamics and change in human society".

He then wrote a scathing critique of the Young Hegelians in two books, The Holy Family (1845) and The German Ideology in which he criticized Bruno Bauer and Max Stirner. In The Poverty of Philosophy (1845), Marx also criticized Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who had made his name with his cry "Property is theft!";. Furthermore, he criticized Feuerbach's conception of human nature in his sixth thesis on Feuerbach as a 'type'; abstract that was incarnated in each singular individual: "Feuerbach resolves the essence of religion in the essence of man. But the essence of man is not an abstraction inherent to each individual. In reality, it is the set of social relations". So instead of finding himself in the singular and concrete individual subject like classical philosophy, including contractualism (Thomas Hobbes John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau), but also political economy, Marx began with the totality of social relations.: work, language and everything that constitutes our human existence. He asserted that individualism was essentially the result of fetishism or alienation from commodities. In Capital, Marx criticizes Smith and Ricardo's labor theory of value.

Diverse sociologists and philosophers, such as Raymond Aron and Michel Foucault, have also traced in the Marxist vision of the end of feudalism as the beginning of absolutism and the separation of the State and civil society, the influence of Montesquieu and Tocqueville, particularly in his works on Bonapartism and the class struggle in France.

Materialist conception of dialectic

The dialectical materialism—expression coined by Gueorgui Plekhanov—is the stream of materialism according to the original ideas of Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx who were subsequently enriched by Lenin and systematized, mainly by members of the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union. This philosophic current defines matter as the substrate of all reality, whether concrete or abstract (thinkings), emancipates the primacy and independence of matter before the consciousness and the spiritual, declares the world's cognitiveness by virtue of its material nature, and applies the dialectics—based on the dialectical laws proposed by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel—to interpret the world, thus overcoming mechanistic materialism. dialectical materialism is one of three components—the philosophical basis—of Marxist-Leninist communism. Denominated Diamatdialectical materialism was also the official philosophy of the former Soviet Union.

Materialist conception of history

Historical materialism (a term coined by the Russian Marxist Gueorgui Plekhanov), also known as the materialist conception of history, is a Marxist methodology that focuses on human societies and their development through of history, arguing that history is the result of material rather than ideal conditions.

This work defends what we call "historical materialism" [...] that conception of the overthrown of universal history that sees the final cause and decisive driving force of all important historical events in the economic development of society, in the transformations of the mode of production and of change, in the consequent division of society into different classes and in the struggles of these classes among themselves.Federico Engels (1880) From utopian socialism to scientific socialism, Prologue to the English edition of 1892.

Marx summarized the genesis of his materialist conception of history in Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859):

The first work undertaken to resolve the doubts that struck me was a critical review of the Hegelian philosophy of law, a work whose introduction appeared in 1844 in the Franco-German analysespublished in Paris. My research led me to the conclusion that, both legal relations and forms of State cannot be understood by themselves or by the so-called general evolution of the human spirit, but on the contrary, they are in the material conditions of life whose whole Hegel summarizes following the precedent of the English and French of the century.XVIIIunder the name of “civil society”, and that the anatomy of civil society must be sought in the political economy.In Brussels, to which I moved as a result of a banishment order issued by Mr. Guizot, I continued my studies of political economy begun in Paris. The general result I came to and that once obtained served as a guiding thread to my studies can be summarized as follows: in the social production of their lives men establish certain necessary and independent relationships of their will, production relations that correspond to a certain phase of development of their material productive forces. The whole of these production relations forms the economic structure of society, the real basis on which the legal and political superstructure is built and which corresponds to certain forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the process of political and spiritual social life in general. It is not the consciousness of man that determines his being but, on the contrary, the social being is what determines his consciousness.

As the material productive forces of society come to a particular stage of development, they are in contradiction with the existing production relations or, what is only the legal expression of this, with the property relations within which they have unfolded there. In forms of development of the productive forces, these relationships become their hindrance, thus opening up a time of social revolution.

By changing the economic base, the whole immense superstructure built on it becomes, more or less quickly. When these transformations are studied, one must always distinguish between material changes in the economic conditions of production and which can be seen with the accuracy of the natural sciences, and the legal, political, religious, artistic or philosophical forms, in a word the ideological forms in which men become aware of this conflict and struggle to resolve it. And in the same way that we cannot judge an individual by what he thinks of himself, we cannot judge these times of transformation by his conscience either, but on the contrary, this consciousness must be explained by the contradictions of material life, by the conflict between the social productive forces and the relations of production.

No social formation disappears before all the productive forces within it develop, and new and higher production relationships never appear before the material conditions for their existence have matured within the old society itself. Therefore, humanity always proposes only the objectives that it can achieve, because, looking better, it will be found whenever these objectives only arise when they are already given or, at least, are being developed, the material conditions for their realization. In broad terms, we can designate as many other times of progress in the economic formation of society the Asian, ancient, feudal and modern bourgeois mode of production.

The bourgeois relations of production are the last antagonistic form of the social production process; antagonistic, not in the sense of individual antagonism, but of an antagonism that comes from the social conditions of life of individuals. But the productive forces that develop in bourgeois society at the same time provide the material conditions for the solution of this antagonism. This social formation closes, therefore, the prehistory of human society.K. Marx (1875) Prologue to Contribution to the Critique of the Political Economy

In Capital, Marx exposes his famous materialist conception of history. According to this point of view, economic factors have been the ones that have driven history and determine what is best called the cultural superstructure of the religious, artistic, legal, philosophical, ethical and political ideas in any society. Historical materialism is an example of the scientific socialism of Marx and Engels, which attempts to show that socialism and communism are scientific necessities rather than philosophical ideals. In conclusion, history is not the development of Hegel's "absolute" spirit, but rather the material product of real and concrete men driven by their socioeconomic conditions.

Analysis of social classes

The concept of social class was not invented by Karl Marx, but by the founders of political economy (Adam Smith…), the founders of the French political history tradition (Alexis de Tocqueville), and the history of the French revolution (Guizot, Mignet, Thierry). For English theorists, the identity criteria of a social class are found in the origin of income: types of income, land rent, profits and wages. These three groups are the main ones for the nation: landowners, workers and businessmen.

Among French thinkers, the term “class” is a political term. For example, for authors like Tocqueville, there are differences between classes when the various social groups compete for control of society. Marx noted his contribution to the understanding of social classes:

Now, for me, that I am not the one who deserves merit for the discovery of the existence of classes in modern society, as well as the struggle that is dedicated to it. The bourgeois historians had put before me the historical development of this class struggle and some bourgeois economists described me the economic anatomy. What I offer is: the demonstration that the existence of social classes is only linked to the historical phases through the development of production, that the class struggle necessarily leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat and that this same dictatorship represents only a transition to the abolition of all classes and to a classless society.Letter from Marx to J. Weydemeyer. March 5, 1852.

For Marx, social classes are part of social reality. The struggles of these social classes point to social change as a lasting phenomenon. These classes are the result of a division of labor mechanism, which developed at the same time as the privatization of the means of production. Social classes arise when the differentiation of tasks and functions stop being a matter of chance to become an inheritance. There is a tendency towards polarization between the two classes most antagonistic to each other. This antagonism is the basis of any transformation that affects the functioning of the social organization and that modifies the course of history. For Marx, the capitalist production process creates two positions: that of the exploiters (entrepreneurs) and the exploited (workers). Individualistic and collective behaviors are explained through these positions in the reproduction of a system. Class conflict is a cultural feature of society. These conflicts are the engine of great social changes. Marx is interested in endogenous changes, that is, those that arise from the functioning of society. The position of the individual in the relations of production (worker or exploiter) is, according to him, the element that allows the definition of the class.

Marxists consider that capitalist society is divided into social classes, of which they mainly consider two:

- La working class or proletariatMarx defined this class as “the individuals who sell their labor and do not possess the means of production”, to whom he considered responsible for creating the wealth of a society (buildings, bridges and furniture, for example, are physically constructed by members of this class; also services are provided by wage earners). Engels points out that the proletariat was born after the industrial revolution for the second half of the centuryXVIII in England and then repeated in all civilized countries of the world.

- La bourgeoisie: those who “own the means of production” and employ the proletariat. They constitute the business class par excellence: their wealth comes from the intellectual administration of business. They appropriate the economic surplus of the whole society by the mechanism of surplus value, capable of confiscating in a non-coercive way (mercantile, rational) the value of work, pillar of all value and wealth.

There are other classes that integrate aspects of the two main ones, or that, being associated with one, manifest new particular features of their own.

- The lumpenproletariat: those who live in extreme poverty and cannot find work regularly. It ranges from the vast mass of unemployed indigents and/or from precarious jobs to extreme marginal sectors such as prostitutes and organized crime soldiers, etc.

- La petty bourgeoisie: it is part of the working people, but to a lesser or greater extent its work creates capital and finds in it its bra, although in levels of accumulation always far inferior to that of the great bourgeoisie. This capital generates the most diverse social segments, mainly intellectual (professional), or commercial (small traders), or real estate (small and medium peasants, urban renters) or financial (small speculators) or directly industrial (small entrepreneurs).

Some authors highlight the distinction in Marx's work between class in itself and class for itself. The first refers to the existence of a class as such and the second to the individuals that make up said class as they are aware of their position and historical situation. Analyzing the situation in Great Britain in the 1840s, Marx notes:

In principle, economic conditions had transformed the mass of the country into workers. The domination of capital has created in this mass a common situation, common interests. Thus, this mass is already a class in front of the capital, but not yet for itself. In the struggle, from which we have pointed out some phases, this mass meets, becoming class for itself. The interests they defend become class interests.Marx, Karl; The Misery of Philosophy, p. 257. Ed. Jucar.

Marx believes that, for there to be no social class, there must be class consciousness: the consciousness of having a common place in society. Marx pointed out that it is not enough for many men to be on the side of a single economic plan for the class spirit to be formed. Class consciousness denotes the consciousness, of itself and of the social world, that a social class possesses and its ability to act rationally in its best interest, therefore class consciousness is required before it can effect a successful revolution and Therefore, the dictatorship of the proletariat.

According to Marxist analysis, the dominant social class organizes society by protecting its best privileges. For this, the State is established, a political instrument of domination: “police and army responsible for maintaining security and public order, the “bourgeois” order. Marx also speaks of "the dominant ideology". In any society, there are ideas, beliefs and values that dominate social and cultural life. These ruling ideas are produced by the ruling class, that is, the bourgeoisie. Therefore, these ideas express the opinion of these classes, that is, they justify it and strive to perpetuate themselves. These ideas penetrate the mind, often working as a world view against its real interests.

Class struggle and modes of production

Engels shared the basic assumptions with Marx that the history of humanity is a "history of class struggles" and that its course is largely determined by economic conditions. Engels says that this formula is limited to written history. Yet Marx did not "invent" the concept of class struggle. In fact, the class struggle has been theorized long before him, by restoration historians such as François Guizot and Augustin Thierry. Marx's fundamental contribution to this concept is to have shown that the class struggle did not end in the French Revolution, but continued in the bourgeoisie/worker opposition in the capitalist era.

In Anti-Dühring and in his later writings, Engels further elaborated the concepts of philosophy of history. Engels's view of history is characterized by a fundamental optimism. Like Hegel, he does not understand human history as an "intricate confusion of meaningless violence", but as a process of development, whose internal law can be perceived through all apparent coincidences.

Therefore, Marx borrows from the classical economists the implicit idea of classes as a factor of production, the history of classes and conflict as a producer of history. To all these theories, Marx brings the concept of the state of the social class as its intrinsic struggle: without struggle there are no classes. Social classes are achieved through perpetual historically determined struggles. Each stage of society that has occurred throughout history can be characterized through a different mode of production.

A mode of production is based on the set formed by the productive forces and the social relations of production that occur in society. In each of the stages of evolution, the mode of production demonstrates a state of society. This is taken as something social, since without productive forces, there can be no doubt about the lack of production. Said productive forces are: the instruments of production, the labor force of men, work objects, knowledge and techniques, organization... Because of all these production activities and through them, men come into contact with each other. Social relations. The production model cannot be reduced to a simple technical aspect, since it is one of the most important concepts for Marx.

Marx considered class conflicts to be the driving force of human history, since these recurring conflicts have manifested themselves as distinct transitional stages of development in Western Europe. Consequently, Marx designated human history as encompassing four stages of development in the modes of production:

- Primitive community: as in cooperative tribal societies.

- Slave society: a development of tribal to city-state; aristocracy is born.

- Feudalism: Aristocrats are the ruling class; traders evolve into capitalists.

- Capitalism: the capitalists are the ruling class, which create and employ the proletariat.

- Communism: society without money, state, private property and social classes.

Communism, socialism and dictatorship of the proletariat

Marx is part of a dialectical thought, as opposed to the mechanism that is present in previous materialism, he sees coexistence between classes as a determining role in the development of history. Through this vision, the proletariat becomes a class in itself and for itself, becoming aware of its class interests, which are: socializing the means of production (socialism) in order to maximize the productive forces, the extinction of the different social classes and the existence of a political state (communism). History continues to be the sum of contingencies subject to the ups and downs of social class struggles. History is not a linear evolution between modes of production, but rather a dialectical transformation of becoming aware of classes that experience class struggle fluctuations at certain moments in history. In this development, the productive forces are increasingly contradictory with respect to the social relations of production, since they do not evolve at the same pace. Beyond a certain level of production, social systems become blocked. A time of social revolution that begins to work, allows the elimination of the old production relations to give way to the development of more coherent relations at the level reached by the productive forces.

Bourgeois democracy is exercised as a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie over the proletariat, where the interests of the latter are opposed to those of private property. On the contrary, the dictatorship of the proletariat is the dictatorship of the most numerous class that does not seek to sustain its situation of dominance but to make class antagonisms disappear. Only in communist society, when it has been broken when the capitalists have disappeared and there are no social classes, only then "will the State disappear and we can speak of freedom". Communism thus constitutes the state of society without class divisions and therefore without class struggle. In The Class Struggles in France from 1848 to 1850, Marx expressed that "the emancipation of the proletariat is the abolition of bourgeois credit, since it means the abolition of bourgeois production and its order. "

In fact, from the moment the work begins to be divided, each one moves in a certain circle of exclusive activities, which is imposed on him and which cannot be left; the man is hunter, fisherman, pastor or critical critic, and has no choice but to remain, if he does not want to be deprived of the means of life; the step that in communist society, where each individual does not have a regular circle of activities, but can developK. Marx and F. Engels (1845) The German ideologyChapter 1, Part II, 4. The social division of labour and its consequences: private property, the State, the "denial" of social activity

Some revolutionaries such as Aleksandr Herzen, Dmitri Pisarev, Nikolai Chernyshevsky, and above all, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, harshly criticized egalitarian communism:

This communism, by completely denying the personality of man, is precisely the logical expression of private property, which is this denial. General envy and constituted in power is but the hidden form in which greed is established and simply satisfied otherwise.Economic and philosophical manuscriptsThird Manuscript (1844), K. Marx.

The contributions of the utopian socialists of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier and Robert Owen were positively valued by Marx and Engels, however they were also harshly criticized for being unrealistic:

These fantastic descriptions of tomorrow's society spring up at a time when the proletariat has not yet attained maturity, in which, therefore, a series of fantastic ideas about its destiny and position are still forged, allowing itself to be carried by the first, purely intuitive impulses, to radically transform society.Communist ManifestoSocialist and Communist Literature (1848), K. Marx and F. Engels,

Marx's communist mode of production is divided into two phases, whose realization would be in the hands of the proletariat organized under the leadership of a revolutionary communist party, and which would disappear as a class during its realization. For Marx and Engels, the industrial working class is the only one that, due to its impossibility of private acquisition, can overcome through the communist synthesis the inescapable contradiction of state socialization: it is the communist negation of society because it cannot be transformed into a new exploiting class, it is the communist negation of the State because only by transforming itself into a public power can it overcome its remnant salaried character of bourgeois society, and it is the communist negation of property because only by distributing according to needs and capacities can it acquire the fruits of the means of production. In the Critique of the Gotha program, a difference is made between a previous communist stage where the individual would buy goods with work vouchers, from a higher stage, in which each person will contribute according to their abilities and receive according to their needs. It was not until the Bolshevik Revolution that the term socialism came to refer to the previous stage of communism.

Marxist conception of ideology

The role of ideology, according to this Marxist conception of history, is to act as a lubricant to keep social relations fluid, providing the minimum necessary social consensus by justifying the predominance of the ruling classes and political power. As historical materialism defines the concept, "ideology" it is part of the superstructure (in German: Überbau) determined by the material conditions of the economic and social relations of production or structure (in German: Basis) and the reflection that produces is called "false consciousness". Like the sophist Thrasymachus, Marx said that "the ideas of the ruling class are the ruling ideas in every age".

"It is not the conscience of man that determines his being, but, on the contrary, the social being is what determines his conscience."K. Marx (1859) A contribution to the critique of the political economyI.

Engels explains that "the true propelling forces that move it remain unknown to the ideologue. His ideas appear to the ideologue "as a creation, without looking for another more distant and independent source of thought;" for him, this is the very evidence, since for him all acts, insofar as thought serves them as mediator, also have in thought their ultimate foundation;. These drivers include both obscure subjective interests and the objective economic constellation. On the other hand, Engels also criticized economistic positions that deny any role for the superstructure. For example, in the Middle Ages "ideology was the dominant instance (religion) but the economy was still the determining instance". Only in capitalism "the dominant and the determining authority coincide".

The foundation of this is the ordinary, non-dialectic concept of cause and effect as rigid opposite poles, totally disregarding their interaction; these gentlemen often forget and almost deliberately that once a historical element has been brought into the world by other elements, ultimately by economic facts, it also reacts and can react on its medium and even on its own causes.Letter from Engels to Franz Mehring; July 14, 1893.

From the inadequacy of the dominant ideology to new conditions, alternative ideologies arise that compete with it, producing an ideological crisis. Marx believed that the dominant ideas are "false" because they reflect the economic interests and preferences of the ruling class. This critique has contributed to an academic distrust of notions such as "objectivity", "neutrality", "universality" and the like.

[D]icho in other terms, the class that exercises the dominant material power in society is, at the same time, its dominant spiritual power. [...] Dominant ideas are nothing but the ideal expression of dominant material relations, the same dominant material relationships conceived as ideas; therefore, the relationships that make a certain class the ruling class, that is, the ideas of its domination. [...]The division of labour [...] is also manifested within the ruling class as a division of spiritual and material work, so that a part of this class is revealed as the one that gives its thinkers (the active conceptual ideologues of that class, that make the creation of the illusion of this class about itself its fundamental power branch), while others adopt before these ideas and illusions a rather passive and receptive attitude, since little active members are [...] The existence of revolutionary ideas in a certain period already presupposes the existence of a revolutionary class [...] as a representative of the whole of society, as the whole mass of society, in front of the single class, to the ruling class.

K. Marx and F. Engels (1845) The German ideologyChapter 1, Part III, 1. The ruling class and the dominant consciousness. How the Hegelian conception of the domination of the spirit has been formed in history.

For Antonio Gramsci, one of the most important functions of the State is to raise the population to a certain cultural and moral level, which contributes to the development of the productive forces and therefore to the ruling classes. The school as a positive educational function and the police and the courts as a negative and repressive educational function form, together with other organizations of a private nature, the apparatus for the political hegemony of the State.

Morality in Marxism

Marx did not deal directly with ethical issues. His materialist conception of history considers morality as a product of the economic base of society. Engels spent more time analyzing morality in his work Anti-Dühring . In it he points out that morality has always been "a class morality"; either it justified the rule and the interests of the ruling class, or, as soon as the oppressed class became strong enough, it represented the irritation of the oppressed against that rule and the interests of said oppressed, oriented to the future”, rejecting so any dogmatic ethics based on eternal or immutable laws.

All of you have to do it on the side, that is, useful. If I ask the economist. Do I obey economic laws if I get money from the surrender, from the prostitution of my body to the pleasure of others? (The laborers in France call the prostitution of their daughters and wives the sad hour of work, which is literally true.) Don't I act in an economic way by selling my friend to the Moroccans? (and the traffic of human beings as a trade of conscripts, etc., takes place in all civilized countries), the economist will answer me: do not operate against my laws, but look at what Mrs. Moral and Mrs.Religion say; my Moral and my Economic Religion have nothing to reproach you. But who do I have to believe now, the political economy or morals? The morality of the political economy is profit, work and savings, sobriety; but the political economy promises me to meet my needs. The Political Economy of Moral is wealth with good conscience, with virtue, etc. But how can I be virtuous if I'm not? How can I have a good conscience if I have no awareness of anything? The fact that each sphere measures me with a different and opposite measure to others, with a measure of morality, with another different political economy, is based on the essence of alienation, because each of these spheres is a certain alienation of man and (XVII) contemplates a certain circle of the essential alienated activity; each of them relates in an alienated way to the other alienation. [...] The relationship of the Political Economy with morals when it is not arbitrary, occasional, and therefore trivial and ascientific, when it is not a misleading appearance, when it is considered essential, can only be the relation of economic laws with morality. [...] Moreover, the opposition between political and moral economy is only an appearance and not such opposition. The Political Economy is limited to expressing moral laws in its own way.Karl Marx (1844) Economic and philosophical manuscriptsThird Manuscripts: III. Human requirements and division of labour under the domain of private property.

Despite Marx's clear antipathy towards the capitalist mode of production, it is not correct to use moral or ethical terms such as good / bad or fair / unfair to describe Marxist analysis, since for Marx communism is not a description of how society should be, but a prediction as a result of the contradictions of capitalism. In addition, Marx valued the innovations of capitalism against feudalism and did not say that communism would be the most just form of society.

For us, communism is not a state that must be implanted, an ideal to which reality must be subjected. We call communism the real movement that overrides the state of affairs today. The conditions of this movement stem from the current premise.K. Marx and F. Engels (1845) The German ideologyChapter 1, Part II, 5. Development of productive forces as a material premise of communism

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: "Marx strives to distance himself from those who engage in a discourse of justice and makes a conscious attempt to exclude direct moral commentary in his own works." Encyclopedia Britannica states that: "Marx was often portrayed by his followers as a scientist rather than a moralist." In fact, Engels coined the use of scientific socialism to differentiate Marxism from previous socialist currents, encompassed under the term utopian socialism. Marx criticized the utopian socialists (Robert Owen, Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier and Étienne Cabet), arguing that their favored small-scale socialist communities would be doomed to marginalization and poverty, and that only a large-scale change in the economic system can bring about real change. The term Marxist socialism is also used to refer to the specific ideas and proposals of Marxism within the framework of socialism.

However, authors after Marx have discussed Marx's moral vision, drawing ethical implications from Marxism. For example, Marx takes the categorical imperative from Kantian ethics, in which he expresses himself: "Act in such a way that use humanity, both in your person and in the person of another, always at the same time as an end and never simply as a means. As Marx points out, in the capitalist he does not see the proletariat as an end in itself, but as a commodity (labor or workforce). In the early writings of the young Marx, it seems that he considered human freedom as the ultimate goal that it can only be achieved with the abolition of private property. Engels affirms that "a truly human morality, which is above class oppositions, and above the memory of them, will not be possible in a social state that has not only overcome class opposition, but has also forgotten it." for the practice of life.”

Manuel Fernández del Riesgo suggests a Marxist ethic based on moral relativism, thus rejecting class morality and justifying revolutionary violence when it serves the purpose of producing a change in the infrastructure capable of generating a new and humanized society and a new type of social relations. The problem is that this position is that it runs into the problem of being and should be, seeing itself as an emotivist ethic, where the statement "the workers are being exploited" it becomes an expression of emotional sentiment towards the proletariat.

Ideas about crime

When Marx understands the right as the fruit of the power of the ruling classes, that is, the bourgeois owners of the means of production, he understands that they define arbitrarily what is legal and illegal, punishing all kinds of behaviors that violate their rights. interests, so for Marx crime "is not something objective proper to necessity, but the mere bourgeois definition of actions that threaten property or the economic system."

In this way, Marx himself maintains that "violations of the law are generally the outbreak of economic factors that are beyond the control of the legislator, but, as the operation of the law on juvenile delinquents testifies, depends to a certain extent of the official society to classify certain violations of its rules as crimes and others as mere faults. This difference in nomenclature, far from being indifferent, decides the fate of thousands of men, and the moral tone of society. The law itself can not only punish the crime, but also improvise it."

Marx's thinking on criminality will directly influence Steven Spitzer and his claim to found a Marxist theory of deviance, currently part of the so-called critical criminology.

Marxist theory of alienation

The Marxist theory of alienation (in German: Entfremdung) is the anthropological interpretation of the psychological and sociological concept of alienation. This interpretation considers that the worker, from the capitalist point of view, is not a person in himself but a commodity—called labor force—that can be represented in his dinerary equivalent, that is, the worker is a certain amount of money that is usable, as a labour force, for the multiplication of the worker. The "Encyclopedia of Marxists Internet Archive" defines alienation as "the process by which people become alien to the world in which they live."

Karl Marx, who was strongly influenced by the Greek philosopher Epicuro in taking a revealing theme for his doctoral thesis: Difference between the philosophy of the nature of Democritus and that of Epicuro. It takes the term and applies it to materialism; specifically to the exploitation of the proletariat and to private property relations. In his approach, he called alienation to the distortions that caused the structure of capitalist society in human nature. Although it was the actor who suffered alienation in capitalist society, Marx focused his analysis on the structures of capitalism that caused such alienation.

In the Economic and philosophical manuscripts of 1844Karl Marx expressed the theory EntfremdungFrom the distance from the self. Philosophically, the theory of Entfremdung se base The essence of Christianity (1841) by Ludwig Feuerbach, who claims that the idea of a supernatural god has alienated the natural characteristics of the human being. In addition, Max Stirner extended Feuerbach's analysis in The only one and his property (1845) that even the idea of "humanity" is an alienating concept for individuals to intellectually consider it in all its philosophical involvement. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels responded to these philosophical propositions in The German ideology (1845).

The theoretical basis of alienation within the capitalist mode of production is that the worker invariably loses the ability to determine life and destiny when he is deprived of the right to think (conceive) himself as the director of his own actions; to determine the character of such actions; to define relations with other people; and to possess those valuable articles of goods and services, produced by his own work. While the worker is an autonomous and self-realized human being, as an economic entity this worker is aimed at goals and diverted to activities that are dictated by the bourgeoisie - owner of the means of production - to extract from the worker the maximum amount of surplus value in the course of the business competition between industrialists.

At present, as most philosophical concepts and social institutions, alienation — as an analytical category — is in a theoretical crisis due to the profound social transformations that have led to post-industrial society. The development of society has complicated the analysis of the social mechanisms of alienation by directing them to new and more subtle forms that need to be studied. Among the authors inspired by Marx, who perform this analysis, stands out, for example, Herbert Marcuse.The Marxist concept of alienation includes four components:

We have considered the act of alienation of practical human activity, of work, in two aspects:

- the worker's relationship with the product of work as with an object that dominates it. This relationship is, at the same time, the relationship with the sensitive outer world, with natural objects, as with a strange world for it and that it is faced with hostility;

- the relationship of work with the act of production within the work. This relationship is the worker's relationship with his own activity, as with a strange activity, which does not belong to him.

[... ]

The work alienated, therefore:

- 3. It makes the generic being of man, both of nature and of his generic spiritual faculties, a being alien to him, a means of individual existence. It makes man strange his own body, nature out of it, its spiritual essence, its human essence.

- 4. An immediate consequence of being alienated the man from the product of his work, his vital activity, his generic being, is the alienation of man from man. If man faces himself, he also faces the other. What is valid in relation to the relationship of man with his work, with the product of his work and with himself, also applies to the relationship of man with the other and with work and the product of the work of the other.

Karl Marx (1844) Economic and philosophical manuscriptsFirst Manuscript: IV. Work alienated

Marxist anthropology and the theory of work

Through his analysis of the generic being and the social being, Marx seeks to advance a description of human nature. In the Marxist anthropological vision, the main characteristic that differentiates men from animals, rather than other qualities like reason, it is the transformation of nature or work.

Humans recognize that they possess a real and potential self. For both Marx and Hegel, self-development begins with an experience of the alienation derived from this recognition, followed by the realization that the real self, as a subjective agent, turns its potential counterpart into an object to be apprehended. Marx further argues that by molding nature into desired forms the subject takes the object as its own and thus allows the individual to actualize as fully human. For Marx, human nature - Gattungswesen - exists as a function of human work.

Fundamental to Marx's idea of meaningful labor is the proposition that for a subject to come to terms with its alienated object, it must first exert influence over literal material objects in the subject's world. Marx acknowledges that Hegel "captures the nature of work and understands the objective man, authentic because actual, as a result of his own labor", but characterizes Hegelian self-development as unduly "spiritual& #3. 4; and abstract. Marx thus departs from Hegel by insisting that "the fact that man is a corporeal, actual, sentient and objective being with natural capacities means that he has real and sensual objects for his nature as objects of its expression of life, or that it can only express its life in real sensual objects". Consequently, Marx revises Hegelian "labor" in "work material " and in the context of the human capacity to transform the nature of the term 'workforce'.

Because of this, it is important to know who controls working conditions and how. In primitive communism, work, the means of production and the fruits of work belong to the collective, there being no exploitation. Capitalism deprives man of the product of his work, thus losing the action of realizing his "potential" 3. 4; human.

The extension of the machinery and the division of labour remove it, in the current proletarian regime, all autonomous character, all free initiative and all charm for the worker. The worker becomes a simple spring of the machine, from which only a mechanical, monotonous, easy-to-learning operation is required.K. Marx and F. Engels (1848) Communist Manifestobourgeois and proletarians

The reason why Marx realized that this activity is totally Aristotelian (since it begins with the representation of an end), was showing that the end is the same beginning. The work is mainly a comprehensive representation that understands the purpose of the object and differs in this respect from the case of animals. The product of human work must exist in the ideal representation of the worker, that is, the desired work is an object that perfectly fulfills one of the functions of human life. In chapter VII of Capital, Marx takes the Aristotelian scheme in which it is the worker who is subordinated to the same end that he himself gives. The work is such that the individual identifies and recognizes himself with what he does: by doing the work, the man also carries out his own power, his power of conceptualization and can improve, therefore, the capacity production of it. Intelligence, since it is relieved through the performance of work, as long as man actualizes his own faculties in his work, will be led to a process of identification: in the product of work, the individual a part of his identity.

Since work participates in the identity of the person, we can say that work is not only having (production), but it must also be an ontological dimension appropriate to work.

That is why Marx accuses the capitalist industrial production model of alienating workers. Indeed, the worker is no longer in this case, in the case of comprehensive representation, since the final product is ignored, and therefore, the reason for his activity. The question regarding identity is then annulled because the only problem is that of remuneration. The human becomes animal, revealing a reflection of mechanical automatism (see Charlie Chaplin's film 'Modern Times'). In this sense, the abolition of slavery can be understood, not as an ethical issue, but rather as a matter of economic interest, since it costs more to keep people in servitude under the framework of slavery than in that of work under the framework of the wage earner (see the film "Queimada" by Gillo Pontecorvo with Marlon Brando).

The transition from socialism to communism implies highly productive labor, capable of ensuring an abundance of consumer items. Only then will society be able to abolish the old estimate according to the quantity and quality of the work supplied and inscribe on its banners: "From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs." In communist society, the amount of work will be evaluated directly by the time (hours) spent and not by means of value and its forms. Under communism, work will be the first vital necessity of men and will become a joy instead of being a heavy burden. To achieve this goal, important changes in working conditions are essential.

Communist work, in the most rigorous and strict sense of the word, is a free work for the good of society, a work that is executed not to fulfill a certain service, not to receive the right to certain products, not for established and established norms in advance, but a voluntary work, without rules, done without taking into account any reward, without putting conditions on the remuneration, a work done for the habit of working in the good of society and for the conscious job (transforms).Lenin (1920) From the destruction of a secular regime to the creation of another new

Merchandise fetishism

Alienation is the transformation of people's own work into a power that governs them as if it were some kind of natural or superhuman law. The origin of alienation is commodity fetishism: the belief that inanimate things (commodities) have human powers (i.e., value) capable of governing the activity of human beings. Marx borrows the word "fetish" by Kant, which was coined and popularized by Charles de Brosses in his 1760 book Du culte des dieux fétiches. As a form of reification, commodity fetishism perceives economic value as something that arises from the basic products themselves, and not from the interpersonal relationships that produce them.

The theory of commodity fetishism is presented in the first chapter of Das Kapital. On the market, the products of each individual producer appear in a depersonalized form as separate examples of a given type of product, regardless of who produced them, or where, or under what specific conditions, thus obscuring the social relations of production. Therefore, in a capitalist society, the social relations between people (who does what, who works for whom, the production time of a commodity, etc.) are perceived as social relations between objects; depending on the social function of the exchange, the objects acquire a certain form (for example, if the function is to make the exchange possible, the object acquires value; if its function is to hire a worker, then the object becomes capital). The result is the appearance of a direct relationship between things and not between people, which means that things (in this case, merchandise) would assume the subjective role that corresponds to people (in this case, merchandise producers).) and people in se "objectify" as merchandise (labor or labor power).

The ultimate form of social alienation, that occurs when a person sees his or her being (oneself) as a commodity that can be bought and sold, because he or she considers every human relationship as a commercial transaction.

Marxist Critique of Religion

Marxism has traditionally been opposed to all religions. The Marxist texts where information on the Marxist conception of religion can be found are: The German Ideology by Marx and Engels, and Philosophy as a Weapon of Revolution by Louis Althusser. The philosophical foundation of the Marxist rejection of religion has been linked to the development of dialectical materialism. Regarding religious alienation, Marx wrote about it, following Ludwig Feuerbach, in the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right that «the foundation of irreligious criticism is: the human being makes religion; religion does not make man. For his part, Engels said the following about religion in:

These various false ideas about nature, the character of man himself, the spirits, the magic forces, etc., are always based on economic factors of negative aspect; the incipient economic development of the prehistoric period has, by complement, and also in part by condition, and even by reason, false ideas about nature.

Marx describes religion as an alienating entity, which sets the goal of reaching God, an impossible situation for a human since God is the deified human essence, that is, humanity has given its best characteristics to God. Religion would make man conformist and would force him not to fight in this world, since this is only a prelude to the real one. The suppression of these conditions and the full realization of human communion is separated from the biological condition, being projected "to heaven" as a divine intervention in a future parousia, particularly in the special case of Christianity, instead of being politically constructed through the abolition of private property and the division of labor. Hence the phrase whose ending would become famous:

Religious misery is, on the one hand, the expression of real misery and, on the other, the protest against real misery. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, as well as the spirit of a spiritless situation. That's it. the opium of the people.

The reference to opium has been given a vulgar interpretation since this is not –as is usually supposed– a narcotic nor a hallucinogen, but a narcotic analgesic. This misunderstanding of the contemporary reader has led to a frequent confusion regarding the Marxist sentence, according to which it would seem that Marx despised religion.

Feuerbach therefore does not see that "religious feeling" is also a social product and that the abstract individual that he analyzes belongs, in fact, to a certain form of society.Karl Marx (1845) Thesis on Feuerbach. Thesis VII.

In Marx, the critique of religion is not a defense of atheism, but the critique of society that makes religion necessary. But the theoretical criticism of any religion is based on the fact that it is conceived as the result of the production of the superstructure of society, that is, of the manufacture of ideologies that a society builds on its own economic modes of production. As Engels says in Anti-Duhring:

All religion, however, is nothing but a fantastic reflection in the minds of the men of those external forces who control their daily life, a reflection in which the earthly forces assume the form of supernatural forces.

For his part, Vladimir Lenin expressed in this way in Attitude of the workers' party towards religion that «this aphorism of Marx is the cornerstone of all Marxist ideology on religion. All modern religions and churches and religious organizations are considered by Marxism as organs of the reactionary bourgeoisie, used to preserve the exploitation and stupefaction of the working class." Lenin said "every religious idea and every idea of God is vileness. indescribable of the most dangerous kind, 'contagion' of the most abominable kind. Millions of sins, disgusting actions, acts of violence and biological contagions [...] are far less dangerous than the subtle and spiritual idea of God dressed in the most intelligent ideological disguises".

Thus, religion is always a conception of political ideas that tend to reaffirm the existing economic structure. This reveals the reason for the reference to an opiate: religion is not considered a form of intellectual degradation nor a mere illusion generated by the ruling classes (a non-Marxist interpretation that would suppress the idea that he had of ideology, that is, the illusion of universality within each class), but rather that religion is, on the contrary, the necessary anesthetic of the entire society against social alienation and of the oppressed classes against their material conditions of existence.

From Marxism, religion is seen as a social and historical reality and is one of the many ideological forms in terms of production of ideas, conscience, representations, and in this specific case of spiritual production of peoples. All these productions are due to the production that arises from the material and the consequent social relations. In this sense, as a religion, Catholicism, depending on historical circumstances, assumes a fundamental role in society.

While the French Revolution declared the goddess reason as the supreme being, Marx expressed that "the critique of religion leads to the doctrine that the human being is the supreme being for the human being", that is, that the being human itself is "the criterion" of philosophical criticism, which he calls his categorical imperative. As a consequence, it is necessary to "throw down all the relationships in which the human being is a humiliated, subjugated, abandoned and despicable being", in order to so that for Marx "the goal is to transform the humanity of the human being into the central criterion for the human being itself" and thus "human emancipation". In an 1879 Chicago Tribune interview, Marx declared "that violent measures against religion are nonsense" but "as socialism grows, religion will disappear" through "social development, in which education must play a role”.

However, there are Christian communists who distinguish themselves from Marxist communism, instead basing their communism directly on religion and drawing social conclusions from some of the early apostles' teachings, for example:

32 And the multitude of them that believed was of a heart and a soul; and none said to be their own whatsoever he possessed, but they had all things in common. 33 And with great power the apostles bore witness to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and abundant grace was upon them all. 34 So there was none among them in need: for all that possessed heirs or houses sold them, and brought the price of what was sold, 35 and laid it at the feet of the apostles; and they divided each according to his need.Acts of the Apostles 4:32-35

Both Marx and Engels criticized in the Manifesto of the Communist Party the form of communism and Christian socialism as "reactionary socialism" of a feudal type, which did not care about the interests of the proletariat:

Therefore, in practice they are always willing to take part in all the violence and repressions against the working class, and in the proseic reality they are resigned, despite all the ampulous rhetoric, to collect also the eggs of gold and to stumble the nobility, love and honor of the cavalry for the vile traffic in wool, beet and aguardiente. Since the priests always go from the arm of the feudal lords, it is not strange that with this feudal socialism comes to confluence clerical socialism. Nothing easier than giving Christian asceticism a socialist varnish. Didn't Christianity also fight against private property, against marriage, against the state? Did charity and alms, celibacy and the punishment of the flesh, monastic life and the Church not preach before the institutions? Christian socialism is the hysopazo with which the clergy blesses the aristocrat's contempt.K. Marx and F. Engels (1848) Communist ManifestoSocialist and Communist Literature

In any case, there have been various theorists who consider that being a Marxist and religious are compatible. Among them we can point to the Irishman James Connolly and various authors within liberation theology such as Camilo Torres and Leonardo Boff. The Christian-Marxist synthesis of liberation theologians replies that Marxism does not imply this assertion and that, if this were the case, the ruling classes impregnated with a religious spirit would also be conformist with respect to their material existence and would even be passive in the face of a conflict with other social classes. For these, on the other hand, religion –and in particular the Christian one– always demands a fight in this world based on a religious community: whether with or without classes depending on how it is understood politically. It must be remembered that for Catholicism the resurrection is the return to Eden on earth and that, even if it depends on God, no individual effort would make sense if it were crowned by a death without return (even if the full realization of humanity could only be achieved socially). and not biologically as in the Christian resurrection), since the salvation of each man according to his effort within the alienated world of the present can only be ensured with eternity and participation in the world to come. This is equally true both for the personal self-realization ideology of the Christian right (Calvinist or at least reconciled with the bourgeoisie), and for the class struggle of the Christian left (Marxist or not), as well as for the original ascetic and apolitical positions. of primitive Christianity.

For a society of producers of goods, whose social regime of production is to behave with respect to its products as commodities, that is to say as values, and to relate its private works, covered in this material form, as modalities of the same human work, the most appropriate form of religion is, undoubtedly, Christianity, with its cult of abstract man, especially in its bourgeois modality, under the form of Protestantism, deism, etc.

Christianity, especially Protestantism, is the right religion to a society in which the production of goods predominates.

The latter in particular gave class form to the internal dichotomy between economic and religious life of the otherworldly medieval West and to its historical peculiarity of fusion between «civil society» and «political society» carefully described by Marx in his work On the Jewish question, whose vision would arrive, along with Nietzsche's opposite, to Max Weber, and which would be linked to the Marxist-Weberian debate on the economic influence of religion.

Bourgeois family and child exploitation

Marx and Engels declared in the Manifesto that labor exploitation by the bourgeoisie in capitalism occurs in the proletariat regardless of age and sex, pointing out that "men, women and children, mere instruments of work, between which there is no difference other than cost." This has ruined the family and education, which is based on private profit and is tearing apart the family ties of the proletarians, turning the children of the proletarian into simple instruments of work, and the bourgeoisie has established a system of sexual looting by having to the widows and children of the proletariat at their disposal.

The birth of this industry is celebrated with the great herodic cross of child abduction. [...] Sir F. M. Eden, who is so proud of the atrocities of the campaign since the last third of the centuryXV until the end of the centuryXVIIIin order to expropriate the people of the countryside from their land, which is so pleased to expropriate this historical process as a "necessary" process to open the way to capitalist agriculture and to "establish the fair proportion between the land of labor and the one for cattle", does not credit the same economic perspicacity when it comes to recognizing the need for the theft of children and the slavery of children to open up the fair transformation of manufacturing into the factory.Karl Marx (1867) The capitalBook I, chapter XXIV. The so-called original accumulation.

This movement which tends to oppose private property the common private property, is expressed animally when it opposes marriage (which is obviously a form of exclusive private property) the women's community, in which women become collective and vulgar property. It can be said that this idea of the women's community reveals the secret of this communism still totally gross and devoid of thought. Just as women leave marriage for general prostitution, like the whole world of wealth, that is, the objective essence of man, passes from the state of exclusive marriage to private property to general prostitution with the community. This communism—which at all times denies the human personality—is only a consequent expression of private property that is in itself negation. [...]

The woman, considered a prey and object that serves to satisfy the collective concupiscence, expresses the infinite degradation of man who exists only for himself, since the mystery of man's relations with his resemblance finds his expression not unequivocal, decisive, public, open, in the relationship of man and woman and in the way of conceiving the immediate and natural generic relationship. [...]Karl Marx (1844) Economic and philosophical manuscriptsThird Manuscript: II. Private property and communism