Martin Luther

Martin Luther (German: Martin Luther; Eisleben, November 10, 1483- ibid., February 18, 1546), born Martin Luder, was an Augustinian Catholic theologian, philosopher, and friar who began and promoted the Protestant Reformation in Germany and whose teachings inspired theological doctrine and culture called Lutheranism.

Luther urged the Church to return to the original teachings of the Bible, which led to a restructuring of Catholic Christian churches in Europe. The reaction of the Catholic Church to the Protestant Reformation was the Counter-Reformation. Her contributions to Western civilization extend beyond the religious realm, as her Bible translations helped develop a standard version of the German language and became a model in the art of translation. His marriage to Catalina de Bora, on June 13, 1525, started a movement in support of priestly marriage within many Christian currents.

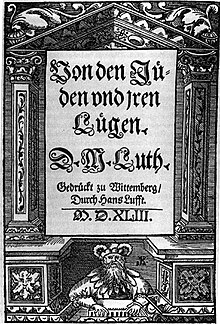

Three years before he died, he wrote a treatise on Christian anti-Judaism called On the Jews and Their Lies, in which he called for the murder of Jews, burning their property and synagogues. His rhetoric was not only directed at Jews, but also at Catholics, Anabaptists, and non-Trinitarian Christians.Luther died in 1546, excommunicated by Pope Leo X.

Biography

Early Years

The son of Hans and Margarethe Luder, Martin was born on November 10, 1483 and was baptized the following morning, the day of Saint Martin of Tours, for which he was named after that saint. In 1484 the family moved to Mansfeld, where his father ran several copper mines. Having grown up in a peasant environment, Hans Luder hoped that his daughter would become a civil servant to bring more honors to the family. To this end, he sent the young Martin to various schools in Mansfeld, Magdeburg, and Eisenach.

In 1501, at the age of 18, Luther entered the University of Erfurt, where he played the lute and was nicknamed The Philosopher.

He received a bachelor's degree in 1502 and a master's degree in 1505, as the second of 17 candidates. Following his father's wishes, he enrolled in the Faculty of Law at this university. But everything changed during a thunderstorm on July 2, 1505. Lightning struck near him while he was returning from a visit to his parents' house. Terrified, he yelled, "Help Santa Ana! I will become a monk!" He made it out alive and abandoned his law degree, sold his books except those of Virgil, and entered the Augustinian monastery in Erfurt on July 17, 1505.

Monastic and academic life

Luther belonged to the order of the Augustinians. His monastic activity consisted of praying, fasting, pilgrimage and confession.

Johann von Staupitz, Luther's superior, concluded that the young man needed more work to distract himself from his excessive reflection, and ordered the monk to begin an academic career.

In 1507 Luther was ordained a priest and in 1508 began to teach theology at the University of Wittenberg. Luther received his bachelor's degree in Biblical Studies on March 9, 1508.

On October 21, 1512, he was "received in the Senate of the Faculty of Theology," giving him the title of Doctor of the Bible. In 1515 he was appointed vicar of his order, eleven monasteries being left in his charge.

During this time he studied Greek and Hebrew to delve into the meaning and nuances of words used in scripture, knowledge that he would later use for Bible translation.

Luther's Theology of Grace

The desire to obtain academic degrees led Martin Luther to study the Scriptures in depth. Influenced by the humanist vocation to go ad fontes ("to the sources"), he immersed himself in the study of the Bible and the early Church. Because of this, terms such as penance and probity took on new meaning for Luther, now convinced that the Church had lost sight of several central truths that Christianity taught in Scripture, one of the most important of which is the doctrine of justification by faith alone. Luther began to teach that salvation is a gift exclusively from God, given by grace through Christ and received by faith alone.

Later, Luther defined and reintroduced the principle of proper distinction between the Law of Moses and the Gospels which reinforced his theology of grace. As a consequence, Luther believed that his principle of interpretation was an essential starting point in the study of the Scriptures. He noted that the lack of clarity in distinguishing the Mosaic Law from the Gospels was the cause of the incorrect understanding of the Gospel of Jesus in the Church of his time, an institution that he blamed for having created and fostered many fundamental theological errors.

The controversy over indulgences

In addition to his duties as a teacher, Martin Luther served as a preacher and confessor at the city's St. Mary's Church. He regularly preached in the palace church, also called & # 34; of all saints & # 34;, because he had a collection of relics from a foundation created by Frederick III of Saxony. It was during this period that the young priest realized the effects of offering indulgences to parishioners.

An indulgence is the remission (partial or full) of the temporal punishment still in place for sins after the guilt has been removed by absolution. At that time, anyone could buy an indulgence, either for themselves or for their dead relatives who remained in Purgatory. The Dominican friar Johann Tetzel had been recruited to travel through the episcopal territories of Albert of Brandenburg (archbishop of Mainz) selling indulgences. With the money obtained by said means, it was hoped to finance the construction of Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome, and buy a bishopric for Alberto de Hohenzollern.

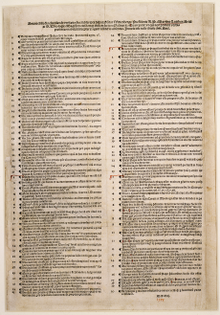

Luther saw this trafficking in indulgences not only as an abuse of power, but as a lie, which, having no basis in Scripture, could confuse people into relying solely on the lie of indulgences, leaving aside the sacrament of confession and true repentance. Luther preached three sermons against indulgences in 1516 and 1517. One night he read a passage from the Letter to the Romans 1:16 and 17 that would lead him to carry out the Reformation: For I am not ashamed of the gospel message because it is power of God so that all who believe may reach salvation, the Jews first and then the Greeks. Well, this message shows us how God frees us from guilt: it is by faith and only by faith. This is what the Scriptures say: The just shall live by faith. But his anger continued to grow and, according to tradition, on October 31, 1517, the ninety-five theses were nailed to the door of the church of the Wittenberg Palace as an open invitation to discuss them. The theses condemned greed and paganism in the Church as an abuse, and called for a theological dispute on what indulgences could give. However, in his thesis he did not directly question the authority of the pope to grant indulgences.

Martin Luther's Ninety-Five Theses were quickly translated into German and widely copied and printed. Within two weeks they had spread throughout Germany and, after two months, throughout Europe. This was one of the first cases in history in which the printing press played an important role, as it facilitated a simpler and more extensive distribution of any document.

Pope's response

After ignoring Luther as a "German drunkard who wrote the theses" and stating that "when he is sober he will change his mind", Pope Leo X ordered the Dominican professor of theology Silvestre Mazzolini in 1518 to investigate the topic. He charged that Luther implicitly opposed the authority of the high priest by disagreeing with one of his bulls, for which he declared Luther a heretic and wrote an academic refutation of his thesis. In it he maintained papal authority over the Church and condemned every & # 34;deviation & # 34; like an apostasy. Luther replied in kind, and a controversy developed.

Meanwhile, Luther wrote his Sermon on indulgence and grace and later took part in the Augustinian convention in Heidelberg, where he presented a thesis on man's slavery to sin and divine grace. In the course of the indulgence controversy, the debate escalated to the point where the absolute power and authority of the pope was called into question, because the doctrines of "Church Treasury" and the "Treasury of Merits", which served to reinforce the doctrine and practice of indulgences, were based on the bull Unigenitus (1343) of Pope Clement VI. In view of his opposition to that doctrine, Luther was branded a heretic, and the pope, determined to suppress his views, ordered him to be recalled to Rome, a trip that was not made due to political problems.

Luther, formerly professing implicit obedience to the Church, now openly denied papal authority and called for a council. He also declared that the papacy was not part of the immutable essence of the original Church.

Wishing to remain on friendly terms with Luther's patron, Frederick the Wise, the pope made a final attempt to reach a peaceful solution to the conflict. A conference with the papal chamberlain Karl von Miltitz in Altenburg in January 1519 led Luther to decide to keep silent while his opponents did so, write a humble letter to the pope, and compose a treatise showing his respects to the Church. catholic. The written letter was never sent because it did not contain any retraction. In the treatise that he later composed, Luther denied any effect of indulgences in Purgatory.

When Johann Eck challenged Carlstadt, a friend of Luther's, to a debate in Leipzig, Luther joined this debate (June 27–July 18, 1519), in the course of which he denied the divine right of throne papal power and the authority to hold the "power of the keys," which according to him had been granted to the Church (as a congregation of faith). He denied that membership in the Western Catholic Church under the authority of the pope was necessary for salvation, maintaining the validity of the Eastern Orthodox Church. After the debate, Johann Eck claimed that Luther was forced to admit the similarity of his own doctrine to that of Jan Hus, who had been burned at the stake.

The gap widens

Luther through the events

In this way, there was no hope of peace. Luther's writings were circulating widely in France, England, and Italy in 1519, and students flocked to Wittenberg to hear Luther, who was now publishing his commentaries on the Epistle to the Galatians and his Operationes in Psalmos (Work on the Psalms).

The controversies generated by his writings led Luther to develop his doctrines further, and his "Sermon on the Blessed Sacrament of the True and Holy Body of Christ, and its Brethren& #3. 4; He extended the meaning of the Eucharist for the forgiveness of sins and the strengthening of faith in those who receive it, also supporting a council to restore communion.

The Lutheran concept of "church" it was developed in his Von dem Papsttum zu Rom (On the Papacy of Rome), a response to the Franciscan Augustin von Alveld's attack on Leipzig (June 1520); while his Sermon von guten Werken (Sermon on Good Works), published in the spring of 1520, was contrary to the Catholic doctrine of good works and works of supererogation (those performed beyond the terms of simple obligation), held that the believer's works are truly good in any God-ordained secular calling (or vocation).

The treaties of 1520

The German Nobility

The controversy in Leipzig (1519) led Luther to make contact with the humanists, particularly Melanchthon, Reuchlin and Erasmus of Rotterdam, and to maintain relations with the knight Ulrich von Hutten, who in turn influenced the knight Franz von Sickingen. Von Sickingen and Silvestre of Schauenburg wanted to keep Luther under his protection, inviting him to his fortress in case he did not feel safe in Saxony because of the papal ban.

Under these circumstances of crisis and confronting the German nobles, Luther wrote To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation (August 1520), where he entrusted the laity, as a spiritual priest, the reform required by God but abandoned by the pope and the clergy. For the first time, Luther publicly referred to the pope as the Antichrist. The reforms that Luther proposed not only referred to doctrinal issues, but also to ecclesiastical abuses: the decrease in the number of cardinals and demands of the papal court; the abolition of the pope's income; recognition of secular government; the resignation of the papacy to temporal power; the abolition of interdicts and abuses related to excommunication; the abolition of harmful pilgrimage; the elimination of the excessive number of holy days; the suppression of nunneries, begging and sumptuousness; the reform of the universities; the abrogation of the celibacy of the clergy; reunification with the Bohemians and a general reform of public morality.

The Babylonian Captivity

Luther wrote doctrinal polemics in the Prelude on the Babylonian captivity of the Church, especially regarding the sacraments.

Regarding the Eucharist, he supported returning the chalice to the laity; In the so-called question of the dogma of transubstantiation, he affirmed the real presence of the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist, but rejected the teaching that the Eucharist was the sacrifice offered to God.

Regarding baptism, he taught that it brought justification only if combined with saving faith in the recipient. However, he maintained the principle of salvation even for those who would later fall and vindicate themselves.

On penance, he affirmed that its essence consists of the words of the promise of exculpation received by faith. For him, only these three sacraments could be considered as such, due to their divine institution and the divine promise of salvation connected with them. Strictly speaking, only baptism and the Eucharist are sacraments, since only they have a "divinely instituted visible sign": water in baptism and bread and wine in the eucharist. Luther denied in his document that confirmation, marriage, priestly ordination and extreme rites were sacraments.

Christian freedom

Similarly, the full development of Luther's doctrine of salvation and the Christian life was set forth in his booklet Christian Liberty (published November 20, 1520), where he demanded complete union with Christ through the Word through faith, the entire freedom of a Christian as priest and king over all external things, and a love for one's neighbor.

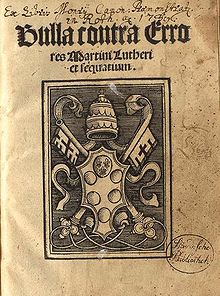

The excommunication of Luther

The pope warned Martin Luther on June 15, 1520, with the bull Exsurge Domine, that he risked excommunication unless within sixty days he repudiated 41 points of his doctrine selected from his writings. At the expiration of this term, it was rumored that Eck had arrived in Meissen with a papal ban, which was actually pronounced on September 21. In October 1520 Luther sent his writing On the Liberty of a Christian to the Pope, adding the significant phrase: "I do not submit to laws when interpreting the word of God". On December 12, Luther personally threw the bull into the fire, which took effect within 120 days, and the papal decree in Wittenberg, defending himself in his Warum des Papstes und seiner Jünger Bücher verbrannt sind and his Assertio omnium articulorum; During the burning of that bull, Luther exclaimed, paraphrasing Psalm 9: Since you have confused the truth [or the saints] of God, today the Lord confuses you. To the fire with you. Pope Leo X excommunicated Luther on January 3, 1521 by means of the bull Decet Romanum Pontificem.

The execution of the prohibition, however, was prevented by the pope's relationship with Frederick III of Saxony and by the new Emperor Charles V who, seeing the papal attitude towards him and the position of the Diet, found it contraindicated to support the measures against Luther. He went to Worms saying that "he would go there even if there were as many demons as tiles on the roofs."

Worms Diet

On January 3, 1521, the bull Decet Romanum Pontificem was published in Rome, by which Pope Leo X excommunicated Luther.

Emperor Charles V inaugurated the imperial Diet of Worms on January 22, 1521. Luther was called to renounce or reaffirm his doctrine and was granted a safe-conduct to guarantee his safety.

Luther appeared before the Diet on April 16. Johann Eck, an assistant to the Archbishop of Trier, presented Luther with a table full of copies of his writings. He asked Luther if the books were his and if he still believed what those works taught. Luther asked for time to think about his response, which was granted. Luther prayed, consulted with his friends and mediators, and appeared before the Diet the next day. When the matter came up in the Diet, Councilor Eck asked Luther to answer explicitly: "Luther, do you reject your books and the errors they contain?", to which Luther replied: «Let me be convinced by the testimonies of Scripture and clear arguments of reason —because I do not believe either the pope or the councils, since it is proven that they have often erred, contradicting themselves — By the texts of Sacred Scripture that I have quoted, I am subject to my conscience and bound to the word of God. That is why I cannot and do not want to retract anything, because doing something against conscience is not safe or healthy. According to tradition, Luther then spoke these words: «I can do no other; this is my stance! God help me!"

In the days that followed, private conferences were held to determine Luther's fate. Before the decision was made, Luther left Worms. During his return to Wittenberg he disappeared.

The emperor issued the Edict of Worms on May 25, 1521, declaring Martin Luther a fugitive and heretic, and forbidding his works.

Exile in the Wartburg Castle

Luther's disappearance during the return trip from Wittenberg was planned. Frederick the Wise arranged for a masked escort on horseback to capture Luther and take him to the Wartburg in Eisenach, where he remained for nearly a year. He grew a broad, shining beard, took on the garb of a gentleman, and assigned himself the pseudonym Junker Jörg (Knight George). During this period of forced stay, Luther worked steadily on the translation of the New Testament.

Luther's stay at the Wartburg was the beginning of a constructive period in his career as a reformer. In his Wartburg "desert" or "Patmos" (as he called it in his letters), he began to translate the Bible, the New Testament being printed in September 1522. In addition to other writings, he prepared the first part of his guide for parish priests and his Von der Beichte (On Confession), in which he denies the obligation of confession and admits the validity of voluntary private confessions. He also wrote against Archbishop Albrecht, whom he forced to desist from restarting the sale of indulgences.

In his attacks on Jacobus Latomus, he advanced his view of the relationship between grace and law, as well as the nature communicated by Christ, distinguishing the goal of God's grace for the sinner, who, by believing, he is justified by God because of the righteousness of Christ, of the saving grace that dwells within sinful man. At the same time he emphasized the insufficiency of the "principle of justification," the persistence of sin after baptism, and the inherence of sin in every good work.

Luther often wrote letters to his friends and allies responding to or asking for their views or advice. For example, Philipp Melanchthon wrote to him asking how to respond to the accusation that the reformers renounced pilgrimage, fasting and other traditional forms of piety. Luther replied on August 1, 1521: “If you are a preacher of mercy, you do not preach an imaginary mercy, but a real one. If mercy is true, you must suffer the real sin, not imagined. God does not save those who are just imaginary sinners. Be a sinner and let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger, and rejoice in Christ who is the victor over sin, death and the world. We will commit sins while we are here, because in this life there is no place where justice resides. We, however, says Peter (2nd Peter 3:13), are looking beyond for a new heaven and a new earth where justice reigns».

Meanwhile, some Saxon priests had renounced the vow of celibacy, while others attacked the validity of monastic vows. Luther in his De votis monasticis (On monastic vows ) advised to be more cautious, basically accepting that the vows were generally taken «with the intention of the salvation or the search for justification». With the approval of Luther in his De abroganda missa privata (On the Abrogation of the Private Mass), but against the staunch opposition of their prior, the Wittenberg Augustinians they made changes in the forms of worship and suppressed the masses. Their violence and intolerance, however, displeased Luther, who in early December spent a few days among them. Returning to the Wartburg, he wrote Eine treue Vermahnung... vor Aufruhr und Empörung ( A heartfelt admonition by Martin Luther to all Christians to guard against insurrection and rebellion ). Even so, Carlstadt and the ex-Augustinian Gabriel Zwilling demanded in Wittenberg the abolition of the private mass and communion under both kinds, as well as the removal of images from churches and the abrogation of the magisterium.

Marriage and family of Martin Luther

On April 8, 1523, Luther writes to Wenceslaus: "Yesterday I received nine nuns from their captivity in the convent of Nimbschen." Luther had decided to help twelve nuns escape from the Cistercian monastery at Nimbschen, near Grimma in Saxony, by carrying them out of the convent inside barrels. Three of them left with their relatives, while the other nine were taken to Wittenberg. In this last group was Catalina de Bora. Between May and June 1523, it was thought that the woman would marry a student at the University of Wittenberg, Jerome Baumgartner, although her family probably denied it. Dr. Caspar Glatz was the next suitor, but Catherine felt "neither desire nor love" for him. for him. It was learned that she wanted to marry Luther or Nicholas von Amsdorf. Luther felt that she was not a good husband, since he had been excommunicated by the Pope and was persecuted by the Emperor. In May or early June 1525 his intention to marry Catherine became known in Luther's inner circle. To avoid any objection from his friends, he acted quickly: on the morning of Tuesday, June 13, 1525, he legally married Catherine, whom he affectionately called "Katy." She moved into her husband's house, the former Augustinian monastery in Wittenberg, and they began to live as a family. The Luthers had three sons and three daughters:

- Johannes, born on 7 June 1526, who later studied laws and became a court official, died in 1575.

- Elizabeth, born on December 10, 1527, died prematurely on August 3, 1528.

- Magdalena, born on May 5, 1529, died in her father's arms on September 20, 1542. His death was very hard for Luther and Catherine.

- Martin, son, born on November 9, 1531, studied Theology but never had a regular pastoral call before his death in 1565.

- Paul, born on January 28, 1533, was a doctor, father of six children and died on March 8, 1593, continuing the male line of the family of Luther through Juan Ernesto, which would be extinguished in 1759.

- Margaretha, born on 17 December 1534, married to the Prussian noble George von Kunheim, but died in 1570 at the age of 36; it is the only lineage of Luther that remains to date.

The War of the Peasants

The Peasants' War or Revolt (1524-25) was a response to Lutheran doctrine, which strongly influenced the lower working class, made up mainly of peasants. This working class implicitly challenged the authority that the nobles had over them. Peasant revolts had been going on on a small scale since the 14th century, but now many peasants mistakenly believed that peasant attacks Luther to the Church and its hierarchy meant that the reformers would help them in their attack on the ruling classes. Since the rebels perceived deep ties between the secular princes and the princes of the Church, they mistakenly interpreted that Luther, by condemning the latter, was also condemning the former. Revolts began in Swabia, Franconia, and Thuringia in 1524, gaining support among the affected peasants and nobles, many of whom were in debt at the time. When Thomas Müntzer came to lead the movement, the revolts led to a war, which played an important role in the founding of the Anabaptist movement. Initially Luther seemed to support the peasants, condemning the oppressive practices of the nobility that had incited many peasants to revolt. Because of Luther's reliance on princes and nobility for support and protection, he was afraid to turn them against him. In Against the Assaulting and Murdering Peasants (1525) he encouraged the nobility to quickly and bloodily punish the peasants. Many of the revolutionaries regarded Luther's words as a betrayal. Others gave up, realizing that there was no support from either the Church or its main opponent. The war in Germany ended in 1525, when the rebel forces were massacred by the armies of Philip I of Hesse and George of Saxony at the Battle of Frankenhausen, in which 6,000 rebels lost their lives. In total, between 100,000 and 130,000 rebels perished throughout the conflict, according to different estimates.

The German Luther Bible

When Luther translated the Bible into German, most of society was illiterate. The Church had the repository of knowledge, its members were studious and educated, in contrast to the illiterate society that acquired its knowledge through oral transmission, memorization and repetition of biblical texts. Luther made possible access to the Bible in German supported by the use of the printing press, facilitating the spread of Protestantism, although he was not the first to print the Bible in German, which he translated from a sacred manuscript into the mother tongue of that nation.. In this way he split the Catholic Church from the German people, and precursored the Protestant Reformation, which occurred thanks to the printing of the Bible that Luther had translated. Luther's intention was that the people would have direct access to the source in the vernacular without the need for knowledge of Latin, making possible the free interpretation of the sacred texts. The translation of the Bible was started during his stay at the Wartburg castle in 1521. The official Bible of that time was the Latin Vulgate, translated from Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek into Latin by Saint Jerome. Luther wanted to translate it from the Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek directly into German, with the intention of making it accessible to the people. Initially it only included the New Testament, since the original texts of the Old Testament were not written in Latin or Greek. The Old Testament was written in Hebrew and Aramaic (languages that lack vowels in the written system; made up of consonant letters). Luther used a Greek edition of the New Testament that was originally edited by Erasmus, a text that was later called the Textus Receptus. During the translation process, Luther visited nearby towns and markets with the intention of investigating the common dialect of the German language. He listened to people talk, so he could transcribe into colloquial language. Indeed, it incorporates "learned syntactic and stylistic elements, but without losing the popular expressive vein" The translation was published in September 1522, which caused great commotion in the Catholic Church. Luther dedicated the German Bible to Frederick the Wise, whom he held in great esteem.

Luther had a poor perception of the books of Esther, Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation. He called the epistle of James a & # 34; epistle of straw & # 34;, finding that very little pointed to Christ and his saving work. He also had harsh words for the Apocalypse, saying he could not "in any way detect that the Holy Spirit produced it". He believed he had reason to question the apostolicity of These books, because the early church classified them as anti-legomena, which meant that they were not accepted without reservation, unlike the canonical ones. Yet Luther did not remove them from his edition of the Scriptures. Luther included as apocrypha those passages which, being found in the Greek Septuagint, were not found in the Masoretic texts available at the time.

It should be noted that Luther's Bible includes the full text of 14 of these documents: the Prayer of Manasseh, Tobias, Judith, the Rest of Esther, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, the Prayer of Azariah, the Canticle of the Three Youth, the Story of Susana, the Story of Bel, the Story of the Dragon, 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees. This is how the Lutheran church, and the Anabaptists (congregated in rural community farms) have used it since then. Although, centuries later, editions devoid of them were made in demand by late Protestant groups, as well as Catholic editions conserving the books. Here are the complete texts of this Bible.

The first complete German translation, including the Old Testament, was published in 1534 in six volumes and was the product of the joint effort of Luther, Johannes Bugenhagen, Justus Jonas, Caspar Creuziger, Philipp Melanchthon, Matthäus Aurogallus, and George Rörer. Luther continued to refine his translation during the remainder of his life, a work that was taken as a reference for the 1546 edition, the year of his death. As mentioned above, Luther's translation work helped standardize Holy Roman German — which would facilitate the unification of the German nation in the 18th century XIX— and is considered one of the pillars of German literature. It also had 117 engravings or illustrations by the painter and engraver Lucas Cranach the Elder, a friend of Luther's, and was printed at Wittenberg in 1534.

Martin Luther in his Commentary on Saint John acknowledged that they had received the Bible through the Catholic Church: «We are obliged to acknowledge to the papists that they are the ones who have the Word of God, that we have received it from them, and that without them we would have no knowledge of it."

Transformations in the liturgy and church government

Luther revised the liturgy in his Deutsche Messe (German Mass) of 1526, stipulating how daily worship and catechesis should be. Even so, he was opposed to a new law of forms and urged that the other liturgies be maintained. Although Luther supported Christian freedom in these matters, he was also in favor of maintaining and establishing liturgical uniformity among those who shared the same faith in a given area. He saw liturgical uniformity as a physical expression of unity in faith, while liturgical variation was a possible indicator of doctrinal variation. He did not consider liturgical change a virtue, especially when done by individuals or congregations, as he was pleased to preserve and reform what the church had inherited from the past. He retained infant baptism, by tradition, against Anabaptist opposition which it only admitted adult baptism, for which reason it condemned its members. Likewise, the paintings and decorations in the churches remained, such as the altarpieces painted by Lucas Cranach the Elder, a friend of Luther, and Luther preached that the images of the saints in themselves they were not bad but everything depended on the attitude of the believers; pictures could be educational and inspirational but not to be adored.

The gradual transformation of the administration of baptism was realized in the Taufbüchlein (Baptismal Booklet) (1523, 1526). In 1529 Luther composed the hymn Strong Castle is our God (Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott) which became popular and became the hymn of the Reformation since it was in German, since until then sacred music it was in latin.

In May 1525, the first evangelical ordination took place in Wittenberg. Luther had rejected the Catholic view of ordination as a sacrament. An ordination service, with the laying on of hands along with a prayer in a solemn congregational service, was considered sufficient.

To make up for the lack of high ecclesiastical authorities due to the fact that very few bishops adopted the reforming doctrine in German lands, Luther maintained from 1525 that secular authorities should take part in the administration of the church. These tasks were not necessarily the exclusive province of secular authorities, and Luther would have preferred them to fall into the hands of an evangelical episcopate. He declared in 1542 that evangelical princes would only be & # 34;emergency bishops & # 34; and he advocated that ecclesiastical powers could be held by Christian congregations, although he decided to wait for the course of events and see what parish priests and scholars did so that they could discover for themselves which were the appropriate persons. The results of his trip to Saxony (1527-29) made him see that the parish priests and scholars were not prepared for such a responsibility, making it necessary to maintain the ecclesiastical structures as they were designed at the beginning of the Reformation.

For the Christmas season, Luther used the figure of Christkind (Child Jesus), instead of Saint Nicholas of Bari, as the one who distributes gifts to children.

Luther had a special interest in education. In his dialogues with George Spalatin in 1524 a school system was planned, declaring that it was the duty of the civil authorities to provide schools and to see that parents sent their children there. He also supported the establishment of primary schools for female education.

Meanwhile, Lutheran churches in Scandinavia and many Baltic states maintained the Apostolic Episcopate and apostolic succession, even those that had adopted Luther's antipapist theology.

Eucharistic Visions and Controversies

The nature of the Eucharist became an important theme in Luther's life. He rejected the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, but maintained the real presence of the body and blood of Christ under the bread and wine of mass. He supported the literal meaning of the words "This is my body", "This is my blood". He synthesized his beliefs on the subject in his Shorter Catechism by writing: "What is the Sacrament of the Altar?" It is the true body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ in bread and wine, given to us Christians to eat and drink, instituted by Christ himself". Refusing to define the mystery of the Eucharist with concepts such as consubstantiation, Luther used the patristic analogy of the doctrine of the Personal Union of two natures in Jesus Christ to illustrate his Eucharistic doctrine "by analogy of the iron put into the fire where both, fire and iron, united in red-hot iron, remain unchanged despite everything", a concept he called "Sacramental Union".

Luther's doctrine differed from that of Carlstadt, Zwingli, Leo Jud and Echolampadius, who rejected the royal presence. Carlstadt, Zwingli and Echolampadius gave different interpretations to what was stipulated by Christ: Carlstadt interpreted the "This" from "This is my body" as the action of Christ aiming at himself. Zwingli interpreted the "is" as "means" and Ecolampadio interpreted "my body" as "a sign of my body". In the controversy that ensued, Luther responds to Ecolampadius in the preface to Syngramma Suevicum (Swabian Writings), expounding his views in the Sermon von den Sakramenten. Wider die Schwärmgeister (Sermon on the Sacrament... Against Fanatical Spirits) and in Dass diese Worte... noch feststehen (These Words... Still Hold Firmes), and more fully in Vom Abendmahl Christi Bekenntnis (Confession regarding the Lord's Supper) (1528).

Because of the dangers of the measures taken by the Second Diet of Speyer in 1529 against Protestantism, and the coalition of the emperor with France and the pope, Landgrave Philip wanted a union of all reformers, but Luther refused. He declared himself opposed to any alliance that would aid heresy, although he accepted the Landgrave's invitation to attend a colloquium at Marburg (1529) to settle the matters in controversy. In said diet on April 19 of that year, 19 delegates, 5 princes and 14 cities protested against the repeal of the truce of tolerance agreed at the Diet of Worms and for this reason Luther's supporters were called Protestants. In Marburg, Luther faced Ecolampadius, while Melanchthon was an antagonist of Zwingli. Although they established an unexpected harmony in other aspects, an agreement could not be reached in the Eucharist. Luther refused to call his opponents "brothers," though he wished them peace and love. Luther was convinced that God had blinded Zwingli's eyes so that he could not see the true doctrine of the Lord's Supper. In his usual polemical style, Luther denounced Zwingli and his followers as "fanatics"; and "demons".

The princes themselves had subscribed to the Schwabach Articles, endorsed by Luther as a condition of their alliance with him. Luther's bases in matters of Eucharistic doctrine were based on a simple and direct understanding of the words of Christ, although he gave importance to the bodily sacrifice of Christ and the fact of offering that same body to the communicants in the Eucharist. When Zwingli excluded the possibility of the real presence due to the inability of Christ's human nature to bilocate or be anywhere other than in a specific place, Luther reaffirmed the integrity of the hypostatic union: Christ is not divided and wherever he is he is. God, even as a man. Luther cited as evidence the three modes of presence according to William of Ockham: "local, circumscribed" (being in one place at a time, taking up space and having weight), "definitive" (detached from space but being where it is needed) and "replete" (filling in all the blanks at once) to introduce the probability that the body and blood of Christ are actually present in the Eucharist.

Luther held that the mere reception of communion is useless without faith. He insisted that the wicked and even the beasts that take and drink the consecrated elements, eat and drink the blood and body of Christ, but drinking and eating "unworthily" is unworthy. they would be judged (1 Corinthians 11:29). Although he did not share the view that the Eucharist was just a simple commemoration, he recognized the existence of a commemorative dimension. As for the effect of the sacrament on believers, he fervently remembered the words & # 34; was delivered for all of you & # 34;, thus emphasizing atonement and forgiveness through death of Jesus Christ.

The Shorter and Larger Catechisms

Frederick III asked Luther in 1528 to visit local churches to determine the quality of Christian education the peasantry was receiving. Luther wrote in the preface to the Shorter Catechism, "Piety! Good God! What abundant misery I have observed! The common people, especially in the villages, have no knowledge of any Christian doctrine, and many united pastors are unable and incompetent to teach". In response, Luther prepared the Shorter and Larger Catechisms. These are instructional and devotional materials that Luther considered to be the foundations of the Christian faith, including the Ten Commandments, the Apostles' Creed, the Our Father, baptism, confession and absolution, the Eucharist, and prayers. The Shorter Catechism was addressed to simple people, while the Greater to pastors.

The Augsburg Diet and the question of civil resistance

The appearance of a common enemy to the entire Holy Empire (the Turkish army) changed the political scenario: now Charles V sought unity to face the new threat, for which purpose the Diet of Augsburg was convened in 1530, in order to definitively clarify the relationship of the Empire with Protestantism. Luther, a fugitive from the Empire, remained safe in Coburg, from there inspiring Melanchthon's speech before the Emperor. Although Martin Luther refrained from maintaining an authoritarian attitude, he did not like Melanchthon's delicacy and caution, because he did not come to propose doctrinal changes, except for the abolition of the papacy. The emperor, forced by the war against the Turks and against the Schmalcald League (an army organized by the princes in defense of Protestantism), managed to ensure unity through the Peace of Nuremberg in 1532, which delayed the definitive solution of the problem until A General Council will be held. Since the Diet of Speyer (1529), the problem had become something of the utmost importance. The point was that the Diet of Speyer had decided in 1526 that it would in no way accept the imposition of the Edict of Worms, which allowed Luther to be killed without fear of sanctions. That same Diet enshrined religious tolerance under the motto Cuius regio, eius religio (that is, To each region the religion of its Lord). Again at the Diet of Speyer in 1529, and faced with the intention of the Catholics to annul the tolerance adopted in 1526, the reformers issued an angry protest complaint, which is why they have been called "Protestants". Now the Peace of Nuremberg established the acceptance of the reformists within the Empire. This situation was forced by the political situation of the moment, since if the Emperor opposed peace, the princes would be legitimized to carry out or support an armed resistance against Carlos V, whose power was beginning to be seriously threatened by the Turks.

This political context had its theological dimension in the so-called question of civil disobedience. Until that moment Luther maintained that he would in no way disobey the Emperor, even if his decision was wrong. In this way he opposed any alliance between the princes, whether offensive or defensive. Martin Luther maintained this attitude even before the League of Esmalcalda. But his position gradually changed when he heard the opinion of jurists who claimed that, in cases of notorious public injustice, the imperial laws themselves granted the right of resistance. It was in 1531 when he accepted the possibility of adopting civil disobedience in his writing Warnung an die lieben Deutschen (1531), as long as it was carried out "for the right causes". Later, in letters written in 1539, he would retract such claims.

In relation to this participation of Luther in political life, it has been said that, if it is usually affirmed that Machiavelli and the humanists sought to emancipate politics from theology, Luther and the first reformers tried to emancipate theology from politics depoliticizing religion. However, it is precisely for this reason that Luther would be converted "forcedly and paradoxically" in a political thinker then:

This has led to a reaffirmation of the state power in which the key lies in the fact that secular authority does not interfere in the domains of the soul (“the soul must neither send it nor send it”), of the Just as religious authority should not interfere with civil laws (the "body and property").

Luther and the Jews

Luther's views on the Jews have been described as racial anti-Semitism by some or religious by others. In other cases as anti-Judaism.

Early in his career he thought that the Jews had not believed in Jesus because of the errors of the Christians and the proclamation of what for him was an impure gospel. He suggested that they would respond favorably to the gospel message if it was presented to them in the right way. When he discovered that this was not the case, he lashed out at the Jews.

In his Von den Juden und ihren Lügen (On the Jews and their lies), published in 1543, he wrote that actions such as burning synagogues should be carried out against the Jews, destroy their prayer books, forbid rabbis from preaching, "smash and destroy" their houses, seize their property, confiscate their money, and force those "poisonous worms" to leave. forced labor or deported "forever". In the opinion of Dr. Robert Michael, it appears that Luther also approved of the murder of Jews.

As the case may be, the truth is that in this libel he asks the German states to act based on these points: "What should we, Christians, do with the Jews, these rejected and condemned people? Since they live with us, we dare not tolerate their conduct now that we are aware of their lies, their insults and their blasphemies… First of all, we must set fire to their synagogues or schools and bury and cover with dirt everything that we do not set on fire, so that no man sees stone or ashes from them again. This is to be done in honor of our Lord and of Christendom, so that God sees that we are Christians and that we do not knowingly condone or condone such lies, cursing and blasphemies to his Son and his Christians… Secondly, I also advise that their houses are leveled and destroyed. Because in them they pursue the same ends as in their synagogues... Thirdly, I advise that their prayer books (sidurim) and Talmudic writings, through which idolatry, lies, curses and blasphemies are taught, be taken from them... Fourthly, I advise that from now on rabbis be prohibited from teaching about the pain of loss of life or limb… Fifthly, that protection on the roads be abolished entirely for Jews. They have nothing to do on the outskirts of the cities since they are not lords, officials, merchants, or anything of the sort... Sixthly, I advise that usury be prohibited, and that all money and all possessions be taken from them. riches in silver and gold, and then all this be kept in a safe place... Seventhly, I recommend putting either a flail or an ax or a hoe or a shovel or a distaff or a spindle in the hands of Jews and Jewesses young and strong and let them eat bread with the sweat of their faces, as was imposed on the sons of Adam."

These harsh words, as they are, have caused many scholars to reconsider Luther's work in a new light, for example, British historian Paul Johnson declared the libel "On the Jews and Their Lies& #34; was the "First work of modern anti-Semitism and a giant step on the road to the Holocaust". Similarly, historians of Nazism cannot fail to point out that four centuries after these essays were written, the Nazis cited them to justify the so-called Final Solution. Some scholars such as Simon and Schuster have even attributed the Shoa or Holocaust directly to Luther's anti-Judaism. Other researchers, such as Uwe Siemon-Netto, refute that view as a historical distortion.

Certainly, the issue may be subject to debate; above all, due to the enormous historical and religious weight that Luther's work possesses. However, it is undeniable that for the philosophers of Nazism the ideas of the reformer paved the way for the creation of the extermination camps. The Lutheran recommendation of a “harsh mercy” or scharfe Barmherzigkeit, which in plain terms meant “absolute intolerance” as a "prophylactic measure& #3. 4; against the Jew was taken by the Nazis as an apology for their vision of the world. During the Nuremberg trial, SA General, Gauleiter of Franconia and Editor of the newspaper Der Stürmer, Julius Streicher pleaded his cause when questioned about the anti-Semitism of his articles, saying: "Anti-Semitic publications have existed in Germany for centuries. For example, a book that I had, and eventually confiscated, was written by Dr. Martin Luther. If this book had been taken into consideration by the prosecution, surely today Dr. Martin Luther would be in my place in the defendant's dock. In this book, "The Jews and Their Lies", Dr. Martin Luther describes the Jews as sons of vipers and recommends setting fire to their synagogues and destroying them." The prosecution could hardly refute such evidence.

Since the 1980s, some bodies of the Lutheran Church have formally denounced Luther's antisemitic writings. In November 1998, on the 60th anniversary of Kristallnacht or the "Night of Broken Glass" The Bavarian Lutheran Church issued the following statement: "It is imperative for the Lutheran Church, which itself is indebted to the work and tradition of Martin Luther, to take seriously his anti-Jewish pronouncements, acknowledge his theological influence, and reflect about its consequences in order to distance himself from every expression of anti-Judaism within Lutheran theology".

Luther regarding witchcraft and magic

Luther shared the medieval character of rejecting all signs that might appear to him to be signs of witchcraft, considering it antagonistic to Christianity. That is why practitioners of witchcraft were persecuted in both Catholic and Protestant territories. Luther is said to have shared some of the superstitions about witchcraft that were common in his time, for example the belief that witches, with the help of the devil, could steal milk simply by thinking of a cow. >Short Catechism Luther teaches that witchcraft was a sin against the second commandment.

Other writings of Luther

The number of books attributed to Martin Luther is quite high. However, some Luther scholars believe that many such works were at least sketched out by some of his friends, such as Melanchthon. Luther's fame gave them a larger potential audience than they would have had from being published under the names of their true authors.

The most comprehensive collection of Luther's voluminous writings is the Weimar Ausgabe (Weimar Edition), which consists of 101 folio volumes, although only a fraction of these writings have been translated.

Some of his books explain how the epistles were established with their canonicity, hermeneutics, exegesis, and exposition, and show how the books of the Bible are integrated with each other. Prominent among them are the writings on the Epistle to the Galatians, in which he compares himself to the Apostle Paul in his defense of the Gospel (for example, the commentary on Luther and the Epistle to the Galatians ).

Luther also wrote about civil and ecclesiastical administration and about the Christian home.

Luther's writing style was controversial, in part because when he was passionate about a subject he would insult his opponents. Like other reformers he was very intolerant of other beliefs and of views opposed to his own and this may have exacerbated the Protestant Reformation in Germany.

His concern about the Ottoman threat is reflected in his Vom Kriege wider die Türken (1529) where he identifies the Turks with the vision of the four beasts from the book of Daniel.

Death

Luther's last trip to Mansfeld was made out of concern for the families of his brothers and sisters, who were still in the Hans Luther copper mine, threatened by the intentions of Count Albrecht of Mansfeld to control that industry to his personal benefit. The controversy involved the four Earls of Mansfeld: Albrecht, Philip, John George, and Gerhard. Luther traveled twice towards the end of 1545 with the aim of participating in the negotiations to reach an agreement. A third visit in early 1546 was necessary to complete them. On January 23, Luther left Wittenberg accompanied by his three children. Negotiations were successfully concluded on February 17. After 8 p.m., Luther suffered from chest pains. Going to bed he prayed saying: « Into your hands I commend my spirit; You have redeemed me, O Lord, faithful God. At one in the morning he woke up with a sharp pain in his chest and was wrapped in hot towels.

Knowing that his death was imminent, he thanked God for revealing his Son, in whom he had believed. His companions Justus Jonas and Michael Coelius shouted: "Reverend father, are you ready to die trusting in your Lord Jesus Christ and confessing the doctrine that he taught in his name? ." A distinctive "yes" was Luther's response. He died at 2:45 a.m. on February 18, 1546 in Eisleben, the town where he was born. He was buried in the Wittenberg Palace Church, near the pulpit.

Her legacy

Luther was the main architect of the Protestant Reformation, in which he played a much more prominent role than other reformers. Thanks to the printing press, his writings were read throughout Germany and influenced many other reformers and thinkers, giving rise to various Protestant traditions in Europe and the rest of the world.

Both the Protestant Reformation and the consequent Catholic reaction, the Counter-Reformation, represented an important intellectual development in Europe, for example: through the scholastic thought of the Jesuits in the case of Catholicism. For his translation of the Bible, Luther is also considered one of the founders of literature in German.

It has been alleged that in the Lutheran territories the absolute power of the kings greatly diminished.[citation needed] The truth is that “the influence of the Protestant doctrine on political approaches has been interpreted according to such varied criteria as to link Protestantism both with the establishment of democratic, totalitarian or absolutist regimes. A first circumstance to keep in mind is the fact that Protestantism entailed a reformulation of the relations between Church and State." Catholics and Protestants waged terrible religious wars against each other. A century after Luther's protests, a revolt in Bohemia sparked the Thirty Years' War, a conflict between Catholics and Protestants that ripped through much of Germany.

Formation of Lutheranism

Luther did not found the Lutheran church as an institution, nor did he plan for its teachings to lead to a new Christian denomination. On the contrary, he expressed, in his own words, his desire that this not happen, when he declared:

- "I pray you leave my name alone. Do not call themselves 'light', but Christians. Who is Luther?, my doctrine is not mine. I haven't been crucified by anyone. How could I, therefore, benefit me, a miserable bag of dust and ashes, give my name to the children of Christ? Let my dear friends cling to these names of parties and distinctions; go to all of them, and let us call ourselves only Christians, according to the one of whom our doctrine comes".

On the other hand, it has been said that "he was a contradictory and unsystematic man to such an extent that one might wonder if Luther would have been a "Lutheran", since Lutheranism implies systematism and this is something difficult to find in him". Despite this, in the historicity of the Protestant Reformation, the name "Lutheran" and "Lutheranism" to refer to the interpretative doctrine and teachings that Luther made about Christianity. This term was used in the same way by the Catholic Church to refer to supporters of the interpretations that Luther had regarding Christianity. However, various self-styled Lutheran churches were consolidating, and with this, that Christian denomination was formed.

Commemoration

The Lutheran liturgical calendar commemorates Martin Luther on February 18, as does the Episcopal Church in the United States. In the Anglican Church he is commemorated on October 31.

Editions in Spanish

- Luther, Martin. Collected works. Air Tower Collection, Cartoné. Editorial Trotta.

Filmography

- 1953: Martin Luther, theatrical film, with Niall MacGinnis as Luther; directed by Irving Pichel. Nominations to Academy Awards for black and white film and art/scenary direction. Relaunched in 2002 on DVD in 4 languages.

- 1974: LutherTheatrical film, with Stacy Keach as Luther.

- 1981: Where Luther Walked, documentary presenting Roland Bainton as a guide and narrator, led by Ray Christensen (VHS launch in 1992), ISBN 1-56364-012-0

- 1983: Martin Luther: Heretic, presented on television with Jonathan Pryce as Luther, led by Norman Stone.

- 2002: Martin Luther, a historic Lion TV/PBS film series Empirewith Timothy West as Luther, narrated by Liam Neeson and led by Cassian Harrison.

- 2003: Luther, German film shot in English, with Joseph Fiennes as Luther and directed by Eric Till.

Contenido relacionado

1053

168

Christ