Martial art

The martial arts (also military arts or military arts) are practices and traditions whose objective is to subdue or defend oneself using a specific technique.

There are various styles and schools of martial arts that typically exclude the use of firearms or other types of modern weaponry. In turn, what differentiates martial arts from mere belligerence or physical violence (street fighting) is the organization of its techniques and tactics in a coherent system; adherence to a philosophy of life or code of conduct and the codification of effective methods proven in antiquity. Currently, martial arts are practiced for different reasons: health, personal protection, personal development, mental discipline, character building and self-confidence. The strict meaning is that of 'military arts', by extension it applies to all kinds of styles of hand-to-hand fighting arts and the use of traditional weapons such as ancient swordsmanship.

Introduction

As far as martial arts of oriental origin are concerned, a beginning is established from the visit of Gautama the Buddha (approx. 500 BC) to China, where he blesses developers with knowledge of the Qí, active principle of traditional Chinese culture that is part of every living being and that could be translated as "vital flow of energy". This invited them to reflect on a new way of harmonic movements where the Qí would circulate correctly through the body and manifest itself on the outside with beauty, softness, ease and power. From the knowledge of energy begins one of the oldest developments of body arts as a martial tool.

However, it was not until the 19th century that the modern concept and term of martial arts emerged. >, which derives from the Chinese characters wǔ shù 武術 and wǔ yì 武藝. For its part, the martial name comes from Mars, the Roman god of war. Oriental martial arts, in some cases, were practiced in closed circles or were distinctive of an elite related to the militia and the nobility, as was the case with the samurai warriors, and their content went far beyond what constituted the training of the troops.

The Chinese-English Dictionary Chinese-English Dictionary (1882), by Herbert Giles, translates wǔ yì as 'military arts'. For its part, the term wǔ shù was not used until 1931, in Mathews' Chinese-English Dictionary. The term also appears in 1920, in Takenobu's Japanese-English Dictionary, in the Japanese translation bu-gei (武芸) or bu-jutsu (武術), as "the trade or performance of military affairs". Other common pronunciations of the character pair 武術 are: mou seut, in Cantonese, and võ-thuật, in Vietnamese. In China, during the Republican Period, from 1928 to 1949, Chinese fighting systems were called guoshu or kuoshu (國術, "national skill")..

The origin of the concept of martial arts is related to the irruption of the Modern Age in East Asia in the XIX century. This phenomenon supposed the transformation of the feudal social structures; the beginning in the use of firearms, which made the traditional forms of struggle lose validity and the disappearance of the principles by which the oriental world was governed. In China and Korea, by contrast, during the 19th century and early XX martial arts and their practitioners were viewed with contempt due to the rise of Confucianism as part of state policy. Consequently, the military component of the nation was weakened.

When the traditional military arts lost their crucial place in the domain of society and the defense of the country, they became an option for the physical and moral development of the nation, in order to improve the population physically and spiritually, which contributed to the loss of much of the knowledge of their practical applications.

Today, traditional Eastern martial arts still include the practice of a precise ethical code that has its roots in Eastern philosophies such as Chinese Confucianism, Japanese Shintoism, and Zen Buddhism (chan 禪). In addition, some martial arts, such as tai chi chuan, are preserved today as a practice to improve physical and mental health.[citation needed]

In China, for its part, chuan fa or kung-fu was invented, which later gave rise to wushu.[quote required] In Japan, on the other hand, do (or 'paths') appeared, such as karate-do, judo , aikido, kendo and kobudo.[citation needed] Through these disciplines, taekwondo, tangsudo, hapkido and hankido] were later developed in Korea. .

The success of traditional martial arts, which arose as a reinterpretation of historical military arts, led to the recovery of fighting systems with and without classical weapons in various cultures. Thus, in Japan, the ancient classical schools known as "koryu budo", are differentiated in relation to modern traditional martial arts, which emerged after the Meiji restoration (1868) or &# 34;gendai budo", and in China, martial arts have evolved into modern wushu.

Some martial arts, and in particular the martial arts originating in China, Japan and Korea, go beyond physical applications, and include knowledge of traumatology, psychophysical regulation ("chi kung" or "qigong"), therapeutics (acupuncture, acupressure, herbalism) and other areas related to traditional Chinese medicine. This is a natural extension of the martial art, because, at an advanced level, the techniques take advantage of a detailed knowledge of the physiology and energy functioning in the opponent's body, in order to increase their efficiency.

In addition, practitioners of various traditional martial arts have begun to rediscover the different methods of building ancient weapons, from sword forging to catapult assembling and siege tower crafting, including replicating armor and dresses; and to investigate about the customs and traditional knowledge originating from these techniques.

Other martial arts have other origins, such as capoeira, of Afro-Brazilian origin.

Boxing is also considered a martial art by some currents.

Classification

One of the general classifications of martial arts is the division between systems without weapons and systems with weapons.

Most martial arts are specialized in one type of weapon or one type of bare hand (unarmed) techniques. However, some claim to be complete systems with and without weapons. Examples of these are most of the classical Chinese martial arts, such as kung-fu type shaolin or Taoist styles; some Japanese martial arts like ninjutsu, and even modern arts like hapkido.

Weaponized systems include as primary weapons:

- The bow

- The spear

- The sword

- The poles of different lengths, thicknesses and materials

There are also multiple secondary weapons such as chains, maces, axes, and knives.

Techniques developed in unarmed systems may include strikes such as punches, open-hand strikes, kicks, or fighting techniques such as grappling, locking, choking, throwing, and pinning, and may address the existence or not of armor by the opponent.

Methods

A common training procedure consists of practicing a group of techniques chained and coded in a series. It is known as structure or, more popularly, as form (kata, poomse, chuan tao, kuen, tao lu, hyung or tul). The practice of forms is a method of learning and training techniques with a specific application.

Another training system is simulated fighting with a partner or exercises in pairs (sparring, randori, kumite, tui shou, rou shou, chi sao, san shou), in which fighting techniques are trained with a partner with the goal of learning, unlike combat or competition, where the goal is victory.

History

Egypt, Greece, Africa and Rome

There are no documents that help to locate exactly when martial arts originated, because this entails a long development process. However, it can be said that the oldest combat method that is known in different civilizations is the fight.

In the tombs of Beni Hassan, in Egypt, are paintings dating from 2000 BC. C. In these, wrestlers are shown practicing a whole series of movements, such as throws and submissions. Nubian wrestlers in Africa were held in high esteem for their skill. In the Egyptian tombs at Amarna, which date to the 14th century B.C. C. in 1350 a. C., paintings appear that show Egyptian wrestlers practicing fighting with short sticks, using protections on their forearms, in addition to wrestling. In murals of Mesopotamian art, there are images of people practicing it as well.[citation needed]

Zulu warriors from southern Africa developed tactics and techniques for fighting with weapons such as the club, spear, and shield. The Shaka warrior (XVIII and XIX) revolutionized mass warfare techniques, with the addition of the assagai (a stabbing spear, with a shorter handle), as well as the way he trained his army and the tactics used against other African tribes and later against the English.

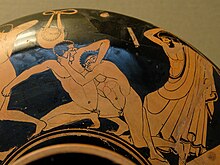

In Greece, three types of combat systems were practiced that not only took part in the Olympia games, but also served to maintain the physical condition of its citizens and prepare them for war: Boxing, wrestling, and pankration, all of them combat methods. In different Greek artistic expressions, different fighting techniques are observed, including the use of "dirty" techniques, such as eye attacks and biting. In turn, they must have developed techniques for the use of weapons. In Sparta, meanwhile, martial practice was emphasized from an early age. As an example of its application, there is the use of the phalanx, a combat formation, which served the Greek army for the expansion of its empire. Some people have suggested that during the occupation of India (326-321 BC)..) by Emperor Alexander the Great (356-323 BC), Greek fighting techniques were absorbed into Indian techniques and these, in turn, were introduced to China by the monk Bodhidharma. However, these hypotheses do not have to date any serious historical support.

In ancient Rome there was fighting, practiced even with weapons, in shows such as gladiator combat in the Roman Colosseum, among others. The Roman army emphasized fighting in groups; while the gladiators were trained in the individual fight. These warriors were slaves who had to be proficient in the use of a large number of weapons, as well as bare-handed combat. Two types of famous gladiators are the Thracian and the Retiarius. The first was armed with a sica (Thracian sword), with a helmet and a small rectangular shield (parma), for which training manuals were published. The retiarius was armed with a trident or harpoon, a net and a dagger. In turn, the gladiators were experts in boxing (they used the caestus ) and in fighting, as seen in frescoes from the period.

China, Korea and Japan

Martial arts in China

References on Chinese martial arts place their origin in 2100 BC. C., although there is no certainty about its real antiquity. The reason for the survival of martial arts has been the development of defense and attack methods in physical confrontations, preponderating the use of the body, fists, hands, elbows, knees, etc., with its maximum expression in war conflicts. The association with religious methods and philosophies in countries like China occurred at the end of the Ming dynasty, due to the appearance of firearms, which caused the techniques of using bladed weapons, as well as fighting with weapons, to begin. to lose its importance in the theater of war.

During the end of the Ming dynasty and during the Qing dynasty, Chinese martial arts began to be seen as methods of improving health and began to be combined with Taoist calisthenics (daoyin) practices, as well as to see themselves as ways to achieve enlightenment.

There are already references to shoubo ("fighting techniques"), wuji ("war techniques") and to ji ji ("fighting skill") before the construction of the shaolin monastery and Bodhidharma's alleged visit to China. The first mention of the involvement of Buddhist monks in the war comes from the thirteen monks who helped capture Wang Shichong's nephew. After which Li Shimin, first emperor of the Tang dynasty, 618 to 907 AD. C., rewarded the monastery. However, there is no reference to a particular style practiced by these monks.

Buddhist monks

The involvement of Buddhist monks in warfare suggests that they were not monks in the strict sense of the word. Buddhist teachings consider killing another human being as the most serious offense and with the worst karma. The novel Shuǐhǔ Zhuàn (The Bandits of the Swamp or The Water Margin) mentions a character named Lu Zhishen ("Lu, the Shrewd") or the Crazy Monk, an army officer who, for having murdered a man, was forced to hide in the Wutai mountain monastery. However, this "monk" who drank wine, ate meat and liked to fight was sent to another monastery, because of his bad behavior.

This type of "monk" appears in other literary works as in the case of Ji Dian ("Crazy Ji"). In turn, in the XVII century, mention is made of many "monks" who lived in the surroundings of the Shaolin monastery, violating the Buddhist rules and doctrines. This could explain why some "monks" had no qualms about taking a life or behaving in a manner opposite to that of a Buddhist monk. During campaigns against Japanese pirates or "wako" in the Ming dynasty, the first mention of a fighting system originating from the shaolin monastery is made. Staff techniques were considered by General Qi Jiguang, while they were criticized by General Yu Dayou (General Qi's comrade-in-arms), who recruited a small group of monks and taught them his own staff fighting techniques, so that they, in turn, could teach them to their classmates.

Ming Dynasty

During the Ming dynasty, General Qi, in his book Ji xiao xin shu (Book of Effective Discipline), mentions that bare-hand fighting techniques are a preparation for combat techniques with weapons. In this book, Qi devotes sections to two-handed sword and staff fighting that were copied from the weapons used by Japanese pirates, who used them with deadly effectiveness. Other sections include spear, trident, saber and shield fighting, firearms, and more.

Qi created the first written routine of bare hand techniques. It combined techniques from a dozen other systems known at his time. He also devised the mandarin duck fighting formation, which included a leader, two soldiers armed with sabers and shields, two with many-pronged bamboo spears (langxian), four with long spears, two with tridents or two-handed sabers, and a cook. If the unit leader was killed, the soldiers of the entire unit were executed.

Qing Dynasty; Republican period (1912-1947); Chinese Revolution (Mao Zedong)

During the Qing dynasty, stories spread regarding Bodhidharma, the shaolin temple, Zhang Zanfeng, and the general Yue Fei, among others, as the founders of many martial styles. In this period, esoteric practices and incantations were used, in the belief that these would give members of pseudo-religious/martial sects the power to resist firearms. The boxer revolution further increased these types of ideologies as inspiration in the face of foreign intervention in China. During the Republican period, an attempt was made to eliminate this type of myth and a more elaborate and technical method began to be used. Historians such as Tang Hao write about the origin of the Chinese combat arts and refute the beliefs that until now were held about these systems. The martial practice of this period was also characterized by its rejection of those elements of display and its focus on practical application in combat. The Nanjing Central Academy of Martial Arts, Zhongyang Guoshuguan (in 1928) was inaugurated, whose objective was to strengthen the nation through the practice of martial arts. In this period, Chinese combat systems were called guoshu ("national skill").

The Chinese Revolution, led by Mao Zedong in 1949, changed all this and focused martial practice on display, creating modern wushu.

Martial arts in Japan

The history of the evolution of Japanese martial arts is sparse; the oldest records come from Chinese sources.

In the History of the Reign of Wei (Weizhi), from the year 297 AD. C., hundreds of populations living peacefully on the Japanese islands are mentioned. In the History of Han (Hou Hanshu), on the other hand, one reads about a period of great instability and war.

Sumo

The oldest reference to the practice of sumo could be found in 23 BC. C., but the first mention as a martial art was recorded more recently in 720 AD. C., in the Nihon soki. However, it uses the Chinese word jueli. In 682 AD C., the word xiangpu is used, in Chinese ("sumo").

Tang Dynasty in Japan; 16th century

During the Tang Dynasty, Japan had the most cultural contact with China. During the first half of the 16th century, Japanese pirates raided the eastern shores of China, their two-handed saber techniques and the skill of archery demonstrated its high technical development, while the uses of the saber sowed terror among the Chinese ranks. The methods designed by Qi Jiguang were introduced to Japan, and were published in the Heiho hidensho (okugisho), a strategy book written by Yamamoto Kanasuke, in the XVI.

Conquest of China (Manchu); 17th and 18th centuries

During the Manchu conquest of China, many emigrants traveled to Japan; among them, Chen Yuanyun (1587 to 1671) or Chen Gempin, in Japanese. In the scrolls of the Kito-ryu school (1779), located in the precincts of the Atago Shrine, in Tokyo, one reads: «Instruction in kempo began with the emigrant Chen Yuanyun."

19th century: karate

In the 19th century, jiu jitsu systems were modified, giving place to judo, by Jigorō Kanō (1860 to 1938); to aikidō, by Morihei Ueshiba (1883 to 1969), and to the techniques of the island of Okinawa or tuidi / to-de and tegumi. These were organized and promoted the creation of karate, a method disclosed by Gichin Funakoshi (1868 to 1957).

Bayonet combat; 1930s

Japanese bayonet fighting methods or "juken jutsu" they were studied by members of the Guoshu Academy in Nanking and included as part of both military and civilian training in the 1930s. In Japan, the Japanese warrior or samurai class combined the practice of Zen Buddhism with that of the arts. of war, in the so-called way of the warrior or Bushido, a trend that has continued to this day.

Meiji Restoration Period

During the Meiji Restoration period, the Japanese warrior code Budo originated. Thus, Zen Buddhism and Japanese martial arts served as support and inspiration in the birth of the nationalist movement that led to the beginning of aggressive Japanese expansionism and World War II.

Martial Arts in Korea

On the Korean peninsula, the earliest evidence of martial practice appears in tombs near the northeastern border of China during the Koguryo kingdom (37 BC to AD 668). Korea was colonized and came under Chinese military control between 108 B.C. C. and 313 d. C. In some frescoes fight scenes can be seen (jueli, in Chinese; kajko, in Korean).

King Sunjo (1567 to 1608) ordered his officers to study the book written by the Chinese general Qi Jiguang, and to prepare a similar book, copying the methods of Ming dynasty soldiers. King Jungjo (1776 to 1800) ordered the manual used by the army to be expanded to include fighting techniques typical of the Japanese. This book is titled Muye Dobo Tongji (Illustrated Manual of Martial Arts). In the introduction to this book, King Jungjo wrote that the only official combat system since the reign of King Kwanhaekun (1608 to 1623) was the practice of archery.

Korean combat systems such as tang soo do (hand of the Tang dynasty), hwa rang do, taekkyon, neikung, kumdo, kuk sool won, among others claim to be entirely Korean and hundreds of years old. However, the Muye Dobo Tongji contradicts them, considering the birth of current Korean martial arts under Chinese or Japanese influence for the most part.

Other countries

An example of other fighting systems that also helped in the formation of empires is the bökh fighting method of Mongolia. Mongol armies used wrestling practice, horseback games, and archery competitions to keep their troops in top physical shape. These skills are still practiced today during the summer festival celebration known as naadam.

In 1295, the oldest known manual containing techniques for sword and shield combat was published in Germany, among many such works published on the European continent. In the Middle Ages in Europe, combat manuals such as the Flos duellatorum (the flower of battle) were published in 1410, which described techniques with and without weapons. In the Viking sagas, combat tactics are discussed as well as strategy.

In Thailand and Cambodia, originated what is known today as muay thai or Thai boxing, and the bokator . However, there are no reliable sources that narrate the origins of this method of fighting. Another form of fighting that shares Thai origin is the krabi krabong which focuses on the use of weapons such as the cane, the shield or double sabers, among others.

In India there are two martial traditions considered to be the most important. The Tamil (Dravidian) and the Sanskrit of the Dhanur-veda ('truth about the bow'). In the first, there are poems written between 400 a. C. and 600 AD. C. where armed conflicts in the south of the country are mentioned. The warriors trained in the use of the spear (vel), the sword (val) and the shield (kedaham). On the other hand, in the Sanskrit tradition, the use of the bow and arrow was considered the most important, as read in the Indian writings of Majabhárata and Ramaiana . In the chapters of the Dhanur-veda,, on the other hand, topics such as the organization of military divisions with war chariots, elephants and horses, infantry and fighting are exposed. Five types of weapons are also described. In turn, some traditions that have survived to date are varma ati (attack on vital points) and silamban (fighting with a stick) of the Tamil Nadu tradition; the kalaripayatu, of the province of Kerala, which currently does not include free combat, but rather pre-arranged combats and the mushti (wrestling), dandi (stick fighting) of North India. Other fighting systems on the Indian mainland are those practiced by the Sikhs, who are called gatka.

In Russia, the need to engage various enemies under adverse weather and terrain conditions led to the development of versatile and instinctive fighting techniques by the Cossacks. Thus began, during the first half of the XX century, an accumulation of martial knowledge that gave rise to the sambo method. .

Also, there are other combat systems of recent disclosure such as arnis / eskrima / kali (in the Philippines) and silat (in Indonesia), which have not yet been publicized, structured in depth or promoted as combat sports in the West due to their wide variety of styles, and their main focus remains self defense and use in armed combat.

The approach to martial arts in the 21st century

At the end of the XX century, different hybrid systems arose, that is, derivatives of traditional martial arts, covering the military combat or combat sports. Some of recent creation and development are: Israeli krav maga, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, Samoan lima lama, Japanese kickboxing, Korean hapkido, jeet kune do (created by Bruce Lee), and mixed martial arts, or MMA. In the case of the Russian systema, this was recovered since during Soviet times it was forbidden to the population, being taught only to Spetsnaz.

References and notes

- ↑ a b R. Patterson, William (2008). «Bushido’s role in the growth of pre-World War II Japanese nationalism». Journal of Asian Martial Arts (in English) 17 (3).

- ↑ a b Victoria, B.D.: Zen at war2006

- ↑ W. Qu, Huang, S., and Shu, S.: Zhongyang guoshuguan shi1996.

- ↑ Graff, D. and Higham, R. (2002). A Military History of China.

- ↑ Yang, Charlotte (August 22, 2016). "Exit the Dragon? Kung Fu, Once Central to Hong Kong Life, Is Waning". The New York Times (in English). ISSN 0362-4331. Consultation on 23 October 2022.

- ↑ Green, T.A., Martial Arts of the World.

- ↑ Poliakoff, Combat Sports in the Ancient World1987.

- ↑ Dervenis and Lykiardopoulos, The Martial Arts of Ancient Greece.

- ↑ G. Tausk, Martial Arts of the World.

- ↑ K. A. C. Gewu, Spring and Autumn of Chinese Martial Arts, 5000 Year1995

- ↑ Acevedo, W., Cheung, M., and Hood, B. (2008), «A lifetime dedicated to the martial traditions. An interview with professor Ma Mingda», Kung Fu Taichi Magazine, 2008.

- ↑ Shahar, M. The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion and the Martial Arts, 2008.

- ↑ Henning, S., The Martial Arts in Historical Perspective.

- ↑ Shapiro, S., Outlaws of the Marsh.

- ↑ Shahar, M., Meat, Wine, and Fighting Monks.

- ↑ Guang, Q. Ji xiao xin shu.

- ↑ Acevedo, W., Chinese martial arts: myths and realities.

- ↑ Mikiso Hane, Brief History of Japan

- ↑ «Excerpts from History of the Kindom of Wei (Wei Zhi)». Asia for Educators (in English) (Columbia University).

- ↑ Ron, R., Martial Arts of the World.

- ↑ Henning, S., Martial Arts of the World.

- ↑ Muye Dobo Tongji: The comprehensive illustrated manual of martial arts of ancient Korea. S. H. Kim.

- ↑ A. Fields: Martial arts of the world.

- ↑ «Historical fencing manuals online - Swords & swordsmanship manual de esgrima italiano-- censo».

- ↑ K. Prayukvong, and L.D. Junlakan: Muay thai, a living legacy.

- ↑ P. B. Zarrilli: Martial arts of the world.

- ↑ «.: Systema Russian Martial Arts - History:.». European Russian Martial Arts Association (in English). Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Consultation on 22 October 2022.

Contenido relacionado

Ecuadorian Language Academy

Mile run

Circus