Maria Zambrano

María Zambrano Alarcón (Vélez-Málaga, Málaga, April 22, 1904-Madrid, February 6, 1991) was a Spanish intellectual, philosopher, and essayist. civic commitment and poetic thought, was not recognized in Spain until the last quarter of the XX century, after a long exile. Already elderly, she received the two highest literary awards granted in Spain: the Prince of Asturias Award in 1981, and the Cervantes Award in 1988.

Biography

Early Years

María Zambrano was born in Vélez-Málaga on April 22, 1904, the daughter of Blas Zambrano García de Carabante and Araceli Alarcón Delgado, both teachers, as was her paternal grandfather, Diego Zambrano. While on vacation with her grandfather Maternal care in Bélmez de la Moraleda (Jaén), María suffered the first warning of what would be a constant throughout her life: her delicate health; On that first occasion, she was given up for dead after a collapse of several hours and a long convalescence.

In 1908 she moved with her family to Madrid and the following year they moved to Segovia when her father obtained the chair of Spanish Grammar at the Normal School of Teachers in the city. María spent her adolescence there and there, the day before On her birthday, her sister Araceli was born, according to her words "the greatest joy of her life".

In Segovia, María began a first love –later forbidden– with her cousin Miguel Pizarro between 1917 and 1921, the year in which the family intervened and Miguel was sent to Japan, as a professor of Spanish at the University of Osaka. After a first moment of desolation, her cousin's escape led her to live a new love experience, recorded in her letters, with Gregorio del Campo, from whom the "baby" would be born, who died shortly after, as described. emerges from the correspondence between the two.

Training

In 1924 his family moved back to Madrid, where he enrolled free of charge (due to his poor health) at the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters of the University. Between 1924 and 1926 she attended the classes of García Morente, Julián Besteiro, Manuel Bartolomé Cossío and Xavier Zubiri at the Central University of Madrid, she also met Ortega y Gasset in an examination panel. In 1927 she was invited to the gathering of the Revista de Occidente, a circle in which, despite her youth, she would assume a mediating role between Ortega y Gasset and some young writers, such as Antonio Sánchez Barbudo or José Antonio Maravall.

In 1928 he began his doctorate and joined the Federación Universitaria Escolar (FUE), where he began to collaborate in the "Aire Libre" of the Madrid newspaper El Liberal. He participates in the foundation of the Social Education League, of which he will be a member. He also teaches philosophy classes at the Instituto Escuela that were interrupted by a new relapse in his health (on this occasion the diagnosis is concrete: tuberculosis).He did not, however, interrupt his collaborations with the FUE and many of his writings. of the.

In 1931 she was appointed Zubiri's assistant professor in the chair of History of Philosophy at the Central University (since, substituting for Zubiri when he is traveling, she would occupy until 1935); at that time she began her unfinished doctoral thesis on "The Salvation of the Individual in Spinoza." She integrated into the apparatus of the republican-socialist coalition, she attended the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic in Puerta del Sol on April 14, 1931; she did not accept, however, the offer of a candidacy to the Cortes as a deputy for the PSOE.

The Spanish Front

On March 7, 1932, María's professional closeness and intense collaboration with José Ortega y Gasset led her to commit what she would soon discover as the "worst political mistake" of her life: the signing of the Manifesto and the creation of the Front Español (FE), with Ortega "pulling the strings in the shadows". That platform of a "National Party" (to which José Antonio Primo de Rivera would try to join without succeeding due to María's personal opposition), very soon showed her fascist profile. Zambrano, making use of his undisputed authority in the collective, and "as he had the power to do so", dissolved the fledgling movement. She could not avoid, however, that the statutes of that & # 39; Orteguian company & # 39; and the initials FE were used by Falange Española.

Disillusioned with party politics, with the notable exception of her fidelity to the Republic during the Civil War, from now on, Zambrano would channel her political concern into the realm of thought. In other words, from this moment on she would no longer participate in party politics, but he would not for that reason abandon the motivation of a political nature in a broad sense that inspired his thought. Thus, his political activity would crystallize on the one hand as a criticism of rationalism and its excesses and, on the other, with the proposal of an alternative and integrating reason, the poetic reason.

Pedagogical Missions

That same year, and in a very different context of life, he met Rafael Dieste through his friend Maruja Mallo at the Valle Inclán gathering, who would henceforth be one of his closest friends; With him and other young people from that group (Arturo Serrano Plaja, Luis Cernuda, Sánchez Barbudo and the one who would later be her husband, Alfonso Rodríguez Aldave) she participated in some Missions in Cáceres, Huesca and Cuenca, environments and chores in which anguish personnel that had besieged it were displaced by the reality of a "Spanish task".

During this period, between 1932 and 1934, María Zambrano collaborated generously in the four cultural circles she frequented: the Revista de Occidente, the poetic gathering of stars of 27 gathered in Los Cuatro Vientos, the youthful Hoja Literaria from Azcoaga, Barbudo and Plaja and the sanctuary of José Bergamín Cruz y Raya, in whose gatherings he met a stunned Miguel Hernández whom it will welcome in a harmony of silences and sorrows.

Many of the members of those circles would end up giving themselves up to the habit of going to have tea at María's house in the Plaza del Conde de Barajas. The thinker moves away from the philosophical cave of the Revista de Occidente and Ortega, and gains an exceptional position among the Spanish poetic intelligentsia. It was the year 1935 and at the beginning of the course María began her task as a philosophy teacher at the Residencia de Señoritas and at the Cervantes Institute, where Machado held the chair of French.

Spain our time, our duty: know it, fulfill it

On July 18, 1936, María Zambrano joined the founding manifesto of the Alliance of Intellectuals for the Defense of Culture (AIDC), collaborating in its drafting and marking the commitment to "the freedom of the intellectual&# 3. 4; with the "people standing up" for an "armed reason". Like her own father and like her admired and admirer Antonio Machado, Zambrano, who never spared lucidity and courage, definitively aligned herself with reality, a human and personal gesture that very much it will soon appear in his work under the heading of "poetic reason".

On September 14, 1936, she married the historian Alfonso Rodríguez Aldave, recently appointed secretary of the Spanish Embassy in Chile, the country to which they traveled in October. On that trip they stopped in Havana, where María gave a lecture on Ortega y Gasset and met who will perhaps be her best friend José Lezama Lima.

Eight months later, in the middle of the Spanish civil war, they return to Spain, the same day that Bilbao falls and the Spanish intellectual diaspora begins; When asked why they return if the war is lost, they will answer: "That's why." Her husband joined the army and she collaborated in the defense of the Republic from the editorial board of Hora de España . She participated in the II International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture (held from July 4 to 17, 1937 in Valencia), where she met Octavio Paz, Elena Garro, Nicolás Guillén, Alejo Carpentier and Simone Weil (dressed in militiawoman). She was appointed Counselor of Propaganda and National Counselor for Evacuated Children, and participated in the reopening and management of the House of Culture of Valencia.

At the beginning of 1938 he moved with his family to Barcelona, where he would teach a course at the university. That year, on October 29, his father died, to whom Antonio Machado dedicated a farewell obituary in number XXIII of the magazine Hora de España (which was never published at the time), later included in his posthumous Mairena. On December 23, twenty-five divisions of the "national army" they approached the offensive of Catalonia. On January 25, Barcelona capitulated and decided to go into exile.

Exile

In the Caribbean and Mexico

On January 28, 1939, María crossed the French border in the company of her mother, her sister Araceli, her husband, and other relatives. In France, María reunited with her husband and after a brief stay in Paris, They leave for Mexico invited by the Casa de España, stopping before in New York and Havana, where she was invited as a professor at the University and the Institute of Higher Studies and Scientific Research. From Cuba she went to Mexico, where —after a series of maneuvers carried out by some former colleagues— she was appointed professor at the Michoacana University of San Nicolás de Hidalgo de Morelia, (Michoacán), which meant a small exile for María within the great exile and caused him to leave Mexico, living for a few years between Puerto Rico and Cuba. relationship with Alfonso Reyes and Daniel Cosío Villegas.

Between 1940 and 1945, he worked intensely in seminars and conference cycles or giving lessons and courses in various Cuban and Puerto Rican institutions, such as the Department of Hispanic Studies of the University of Puerto Rico, the Association of Graduated Women and the Ateneo, or the Assembly of University Professors in exile meeting in Havana. In parallel, she continues to publish articles and some books such as The Confession: Literary Genre and Method , The agony of Europe or The living thought of Seneca . World War II prevents him from reuniting with her sick mother and her sister Araceli, a widow and on the brink of madness, who survive in Nazi-occupied Paris.

America, Havana, Rome, Paris

With the French capital finally liberated, the slow procedures for her visa will mean that when María arrives in Paris her mother is already buried, and her sister "buried alive", a situation that leads the Spanish thinker to make the decision not to separate from Araceli again. Thus, in 1947, the Zambrano sisters settled in an apartment on Rue de L'Université, a temporary home that María's husband joined in March of that year. Coexistence turned out to be untenable.

In 1948, alone and together until the end, María and Araceli Zambrano moved to Havana, and from there to Mexico and back to Havana. But the economic situation begins to be oppressive and they decide to return to Europe. Their condition as wandering beings in continuous exile begins to be almost obsessive. In 1949 the Zambrano sisters returned to Europe, settling in Rome until June 1950, when the Italian government refused to extend their residence permits. They go to Paris where María meets her husband again, the relationship will be brief and finally Rodríguez Aldave and his brother (with whom he has lived for the last three years, since 1947), left for Mexico. During that period, María Zambrano became friends with the French intellectual Albert Camus, who gave him his support so that Zambrano could publish a translation of his work El hombre y lo divino in the Gallimard publishing house: this project would be cut short by the accidental death of Camus in 1960.

The Zambrano sisters remained in Paris until March 1953, when they again moved to Havana. But the initial euphoria of the Caribbean reunion will dissolve in the tide of the Cuban political situation, Araceli's longings, María's love affair with Pittaluga and her own ghosts.In June 1953 a ship returned them to Rome.

The longest Roman period of the Zambranos followed (1953-59); María lived in it a fruitful friendship with Italian intellectuals such as the sisters Elena and Silvia Croce, or Elemire Zolla and his partner Vittoria Guerrini (alias "Cristina Campo"), and recovered her relationship with old friends such as Diego de Mesa (his student at the Instituto Escuela), Carmen Lobo, Nieves de Madariaga, Tomás Segovia, Jorge Guillén, or the Mexican Sergio Pitol. His economy and health, always weak, were comforted by the generosity of Timothy Osborne. Tireless, Maria continues to write. From his effort, among a wide range of articles, essays and books, and a spectrum that opens up between tragic history, painting and poetic reason, will come out masterpieces such as Spain, dream and truth or The Spain of Galdós.

In September 1957, María received a sentence from a Mexican court announcing her divorce from Rodríguez Aldave, accused of abandoning the home and other charges that are not cited and declared 'failed to appear' (without having received any summons). That same fall, she met the Venezuelan poet and singer Reyna Rivas who, with her husband, Amando Barrios, became friends, mediators, and protectors until the last moment. Her Roman house became famous for its gatherings, for its songs and dances, and for its overflowing population of cats. The summer and autumn of 1958 take place largely in Florence, where she is in contact with the painter Ramón Gaya.

After a period of five months in Trèlex-sur-Nyon (Switzerland) in the house rented by their cousin Rafael Tomero, the Zambrano sisters (and their court of cats that accompanied Araceli wherever she moved) returned to Rome, where he also joins them at "Villa Riccio" her aunt Asunción of her during the first months of 1960. In April 1962, Araceli traveled to Mexico to try to agree with Rodríguez Aldave a pension for María with more than negative results. Another setback was the expulsion order from the city of Rome, signed by a senator with a fascist past in September 1963. The reason: the cats. Through the mediation of Elena Croce, the Ministers of Justice and the Minister of the Interior intervened, postponing the process. On September 14, 1964, after a new complaint and its subsequent "sanitary-civic" inspection, the Zambranos and thirteen cats left Rome for France with a notice to the French police that it was about &# 34;dangerous people".

"The Piece"

Contemplating the old house of “La Pièce” for the first time, in the French Jura, Maria said: "It looks like an abandoned convent, but it is funny"... She lived in it until 1977. The The solitude of the little house in the forest would be seen from time to time animated by visits from Spanish and Italian friends and cousins. In it, the Spanish thinker concluded, expanded or forged works such as: The tomb of Antigone , Man and the divine or Forest clearings . It is during this period that his work began to be appreciated in Spain after the publication in the Revista de Occidente, in February 1966, of the article by José Luis López Aranguren Los sueños de María Zambrano, which was followed by the works of José Ángel Valente in Ínsula and José Luis Abellán. Fragments of her work have also been published in Papeles de Son Armadans and Caña Gris .

A project to move to Naples at the beginning of the 1970s did not prosper due to administrative delays and due to the deteriorating health of Araceli, who finally died on February 20, 1972. The death of her sister made her leave her house in the forest, to which he would not return until two years later. Stays in Rome, tourist trips around Greece, all with the company and generosity of his patron Timothy Osborne and his second wife. In 1974 she returned to "La Pièce", where she is assisted and accompanied by her cousin Mariano and Rafael Tomero, hers by three of her dogs and some surviving cat.

From 1975 is the poem that Lezama Lima dedicated in Fragments to his imam, two years before the death of the Cuban, whom María baptized with the title of true man:

Mary has become so transparent / we see her at the same time / in Switzerland, in Rome or in Havana...

But the deterioration of his physical health is progressive; in 1978 he moved to Ferney-Voltaire, where he would stay for two years; In 1981 she moved to Geneva and the Asturian colony in that Swiss city names her Adoptive Daughter of the Principality of Asturias, the first of a long and belated list of recognitions. It seemed that everyone was in an irrepressible rush to entertain her.

Last years and recognitions

In 1981 she was awarded the Prince of Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities, in its first edition. In turn, the city council of Vélez-Málaga, her hometown, named her Favorite Daughter. The following year, on December 19, the Governing Board of the University of Malaga agreed to appoint her as Doctor honoris causa.

After a relapse in her health and the doctors declaring her hopeless, the already elderly but still lucid thinker recovered and on November 20, 1984, María Zambrano finally returned to Spain after almost half a century of exile. She settled in Madrid, a city from which she would leave on a few occasions. In this last stage her intellectual activity was, however, tireless. She also continued her official recognition: she was the Favorite Daughter of Andalusia in 1985, and in 1987, the foundation that bears her name was established in Vélez-Málaga. Finally, in 1988 she was awarded the Cervantes Prize. She died in Madrid on February 6, 1991, and was buried between an orange and a lemon tree in the Vélez-Málaga cemetery, where the mortal remains of her "dos Aracelis", her mother and his sister. On her tombstone can be read as an epitaph, the verse of the Song of Songs , "Surge amica mea et veni".

She continued to receive posthumous awards, many of them from regional claims: Favorite Daughter of the Province of Malaga in 2002. On November 27, 2006, the Ministry of Public Works baptized the central railway station of Malaga with her name. In 2008 she launched the maritime salvage tugboat, María Zambrano (BS-22). The Central Library of Philology and Law of the Complutense University of Madrid, her Alma Mater, also bears her name. On April 28, 2017, the Plenary of the Segovia City Council unanimously approved the granting of the title of Adoptive and Favorite Daughter of Segovia. The city's university campus also bears her name.

In the La Galera neighborhood of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, a street bears his name. Calle María Zambrano-Philosopher-.

Philosophy

For María Zambrano, philosophy begins with the divine, with the explanation of everyday things with the gods. Until someone wonders what are things? then the philosophical attitude is created. For Zambrano there are two attitudes: the philosophical attitude, which is created in man when he asks something, out of ignorance, and the poetic attitude, which is the answer, calm and in which, once deciphered, we find the meaning of everything. A philosophical attitude communicated with a very peculiar language and a creative exposition of her way of thinking, which determine her literary style, and which, ultimately, would constitute the basis of what she herself will call hers & # 34;method".

The question and its method

He establishes it under two great questions: the creation of the person and poetic reason. The first of them would present, let's say, the state of the question: the being of the human being as a fundamental problem for the human being. And what the human being is constitutes as a problem for the human being, because his being is presented in principle as longing, nostalgia, hope, and tragedy. If satisfaction were his lot, he certainly would not propose his own being as a problem.

The theme of poetic-reason, on the other hand, without having been specially and systematically exposed in any of his works, nonetheless underlies all of them to the point of constituting one of the fundamental nuclei of his thought. Poetic-reason is built as the appropriate method to achieve the proposed end: the creation of the person. Both themes addressed extensively, agglutinate as adjacent all the other issues discussed. Thus, the creation of the person is closely related to the theme of the divine, with that of history and dreams, and poetic-reason with the relationship between philosophy and poetry or with the insufficiency of rationalism.

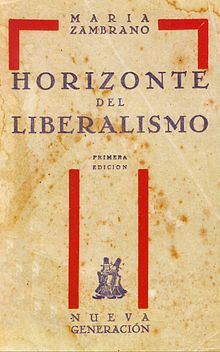

Politics

All the work of María Zambrano is structured by a political spirit that manifests itself in a very diverse way throughout her thought. Her political activity is more direct during the years that preceded the establishment of the Second Republic and, therefore, Of course, during the Civil War. However, it is true that Zambrano refused to participate in party politics, which is why she rejected the position of deputy for the Courts of the Republic that Jiménez de Asua offered her, opting instead for her philosophical vocation.. However, it cannot be said that Zambrano abandoned politics for philosophy, but rather that he chose to do politics from the very root of thought, since, as he explains in his first book, Horizonte del liberalismo (1930), "one becomes political whenever one thinks of directing life" and this is precisely what she aspired to achieve through the exercise of her poetic reason and her criticism of all movements of a fascist or authoritarian nature, as well as also with his profound critique of discursive reason and rationalism.

The phenomenology of the divine

In his prologue to the 1973 edition of El hombre y lo divino, Zambrano commented that “el hombre y lo divino” could very well be the title that best suited his entirety. production. And indeed, man's relationship with "the divine", with the dark root of the "sacred" outside and within himself, of that "being" that has to give birth, to vision, is a constant throughout his work. Phenomenology of the divine, phenomenology of the person or phenomenology of the dream, it is always an inquiry that aims at the unveiling of «what appears», the phainómenon that in its appearance constitutes what being human is. An essential search, therefore, a search for the sacred, elusive essence of the human that nevertheless shows itself in multiple ways, under aspects that we have called "the gods", "time" or "history", for example.

From the dawn of history, when man was immersed in a sacred universe, until the moment of consciousness in which history is assumed responsibly by the individual in the process of becoming a person, there has been a long process during which that individual has been ordering reality, naming it, at the same time that he assumed the challenge of the question in tragic moments, moments in which the gods were no longer the adequate answer. This long process is described by Zambrano as the passage from a poetic attitude to a philosophical attitude. Poetry, Zambrano thinks, is an answer, philosophy, on the other hand, is a question. The question comes from chaos, from emptiness, from hopelessness even when the previous answer, if there was one, no longer satisfies. The answer comes to order the chaos, makes the world walkable, kind even, safer.

To deal with reality poetically, Zambrano thinks, is to do it in the form of delirium, and "in the beginning it was delirium", and this means that the man felt that he was being watched without seeing. Reality appears completely hidden in itself, and the man who has the ability to look around him —although not at himself— supposes that, like him, what surrounds him also knows how to look, and it looks at him. Reality is then "full of gods," it is sacred, and it can possess you. Behind the numinous there is something or someone who can possess it. Fear and hope are the two proper states of delirium, a consequence of the persecution and of the grace of that "something" or "someone" who looks without being seen.

Mythical gods are presented as an initial response; the appearance of these gods is a first ordered configuration of reality. Naming the gods means getting out of the tragic state where the indigent was plunged because by naming them they can be invoked, win their grace and appease fear.

The gods, then, are revealed by poetry, but poetry is insufficient and there comes a time when the multiplicity of the gods awakens in the Greeks the yearning for unity. "Being" as identity appeared in Greece as the first question that, not yet being entirely philosophy, pulled man out of his initial state because it signaled the appearance of consciousness. The first question is the ontological question: "What are things?" Born, according to Ortega, from the emptiness of being of the Greek gods, this question would give birth to philosophy as tragic knowledge. Every essential question is, for Zambrano, a tragic act because it always comes from a state of indigence. He wonders why it is not known, why something is ignored, why something is missing; ignorance is the lack of something: knowledge or being. These tragic acts are repeated cyclically, because the destruction of mythical universes is also cyclical. The gods appear by a "sacred" action, but there is also a sacred process of destruction of the divine. The death of the gods restores the sacred universe of the beginning, and also fear. Every time a god dies, a moment of tragic emptiness happens for man.

During the time between the advent of the first gods and the establishment of the Christian god, the discovery of individuality had happened, along with an internalization of the divine. The birth of philosophy had given rise to the discovery of consciousness, and with it, to the loneliness of the individual. The divine had taken on the appearance of the extreme extrapolation of rational principles. For this reason, the god that Nietzsche killed was the god of philosophy, the one created by reason. Nietzsche decided, according to Zambrano, to return to the origin, delve into human nature in search of the conditions of the divine. With Nietzsche tragic freedom was forged according to Zambrano, exultant according to Nietzsche himself and with it the recovery, in the divine, of everything that, defined by philosophy, had been hidden. In this way, Nietzsche destroyed the limits that man had established for man; he recovered all his dimensions, and of course "the inferos", the hells of the soul: his passions. And in hell: darkness, nothingness, the opposite of being and anguish. Nothing then ascended from the infernos of the body and entered consciousness for the first time, occupying the places of being there.

Nevertheless, nothingness, threatening to being when it tries to consecrate itself, is also a possibility, because when an absence makes itself felt and this reminds us of Sartre, one suffers: the nothingness suffered as absence is nothingness of something, for which reason it is also a possibility of something. The nothingness of being points to being as its opposite. But what kind of "being"? That of the Greeks had been transformed from ontological to theistic-rational, and this had drowned in existential abysses. That concept was therefore not recoverable. But the "origin" was. And to "being" as "origin", to that nothing at the beginning, to that place without space and without time where "nothing was different", to the pure sacred, is what Zambrano tried to return to or arrive at. That sacred, is nothing but the pure possibility of being. From that "nothing" man would have to take upon himself the responsibility of creating his being, a being that is no longer conceptual but historical; create himself from nothing, under his own responsibility as soon as he was born from him, with the freedom that the emergence and acceptance of consciousness gives him. From here the long process of creating the person can begin.

Rationalism and history

Rationalism is an expression of the will to be. It does not pretend to discover the structure of reality, but establishes power from a presupposition: reality must be transparent to reason, it must be one and intelligible. Rationalism, like all absolutism, somehow kills history, stops it, because it abstracts time. Located between definitive truths, man stops feeling the passage of time and its constant destruction, he stops feeling time as opposition, as resistance, he stops knowing that he is in a perpetual struggle against time, against the nothingness that comes his way. If all history is construction, architecture, the dream of reason, absolutism and monotheistic religions is to build above time. Consciousness, in that artificial timelessness of the eternal true, cannot awaken, since consciousness arises at the same time as personal will and this grows with resistance.

The problem that concerns Zambrano is “humanizing history and even personal life; achieve that reason becomes an adequate instrument for the knowledge of reality, above all of that immediate reality that for man is himself. Humanizing history: assuming one's own freedom, and this through the awakening of personal conscience, which will have to assume time, and even more: the different times of the person.

The creation of the person

The same parameters with which Zambrano defines social history, is applied by her to personal history, and it should not be surprising, since history, everyone's, is made by individuals who project their fears on a social level, their anxieties, their desires, their abuses, their ignorance, their desires. Social deformations are the institutionalization of personal deformations, and constitutions, the price that each one pays for consensually attenuating his own vital anguish. Thus, the deification of some, the alienation of others (idolatry and sacrifice), the instrumentalization of reason and the temporary structure are guidelines correctly applicable to the History of all, the one that is built in community and to that other history that is the argument of every human being, suffered in History and under it.

Man as a being who suffers from his transcendence

Man is not only a historical being, the one whose time is successive, time of consciousness applied to reality as a succession of events. Man is above all that being destined to transcend, to transcend himself by suffering this transcendence, a being, man, in perpetual transit that is not only a passing but a passing beyond himself: of those characters that the subject goes through. dreaming about himself. That man is a transcendent being means that he has not finished making himself, that he has to create himself as he lives. And if being born is coming out of an initial dream, living will be coming out of other dreams, successive ones, through successive awakenings.

The phenomenology of time

The structure of the person is elaborated, like history, on another structure: the temporal one. But although history conforms to multiple times, these are always included within the historical time itself: the successive one; temporal multiplicity means only the multiplicity of rhythms, the "tempo" of the connections between the event, its memory, and its projection. Subject tenses imply something else. Schematically, they can be distinguished:

- Time ahead or time of conscience and freedom, measurable in its three dimensions (passed-present-future);

- Time of the psyche or initial timeliness, time of dreams, where thought has no place, nor freedom. In this timelessness the subject does not decide, does not move but is moved by circumstances;

- Creation time or states of lucidity, another type of timelessness, but unlike the former, creator. The subject is not found Low the time, as in the timeliness of the psyche, on Time. This timelessness can give rise on the one hand to the discoveries of art or thought, and on the other, to personal discovery or what Zambrano understands by "creation of the person". These moments of lucidity in which the time of consciousness is suspended are those in which the “desperts” occur.

The way I dream

The phenomenology of the dream form supports the study of times based on the consideration that in human life there are different degrees of consciousness, and above all, different ways of being asleep or subjugated consciousness. María Zambrano saw the need to proceed with an examination of dreams, not so much in their content (psychoanalysis had already dealt with this) as in their form, that is, in the way these states present themselves. He thus distinguished between two forms of sleep:

- Dreams of the psychewhich correspond to the timeliness of the psyche, and among them mainly the dreams of orexis or desire and dreams of obstacle.

- Dreams of the person, also called dreams of awakening or dreams of purposewhich are those who seek the person the vision necessary for their fulfillment. When they arise during the vigil, they are called Real dreamsand they must be deciphered as enigma.

The ethical question: the essential action

The person's dreams demand, on their part, an action, and the only possible action, under the dream, is to wake up. The action is completely different from the activity in that it is a free action that corresponds to the person while the activity is the movement of the character, that continuous activation that is also characteristic of the mind when it acts out of control. This is the same distinction that Zambrano makes between transiting and transcending: the movement of the character is a transit; that of the person is transcendence, a going beyond himself creating himself. The action of the person is always an essential action: it is directed towards the fulfillment of his finality-destiny, which is equivalent to saying that, in his action, the person fulfills himself as such.

The action always comes from a subject, but from a subject that is, above all, will, since there is another part of the subject, the self, to which consciousness is properly attributed. This difference is important in understanding that consciousness often opposes any kind of awakening. The self, knowing that it is vulnerable, acts as an implacable sovereign, defending the kingdom of reason, of laws and habits, erecting walls that isolate it from the extraconscious outer space. The sovereign Yo is terrified of the idea of seeing what is well established shake; he fears more than anything knowing that his kingdom, established in a known space and time and possessed by him, is like a ship sailing on the sea of timelessness. But Zambrano warns: "if such a vigil were fulfilled perfectly, the sovereign subject would spend his life in a state of sleep." Fortunately it is not so; the sovereign is vulnerable, and breaches can be opened in the walls that allow something of the external timelessness to pass through, something yet to be interpreted, something with which to reconstruct reality, another reality, something, above all, that will modify the person since that any comprehensive action fulfills its destiny in it, which is none other than, as Heidegger thought, "to be comprehensively."

Poetic Reason

María Zambrano proposes poetic reason, different from Ortega's vital and historical reason and Kant's pure reason. Zambrano's reason is a reason that tries to penetrate the depths of the soul to discover the sacred, which is revealed poetically. The poetic reason is born as a new suitable method for the achievement of the proposed end: the creation of the individual person.

For Zambrano, man, the self, is endowed with a substance within, being, that being is his feelings, his deepest ideas; the most sacred of the self and of a conscience. Through these substances he must seek the unity of himself as a person. Being is innate, it comes from the first day we exist, even without being conscious; consciousness is created little by little as soon as doubts arise.

The being is encoded by the poetic word, that word must be decoded by consciousness, and this in turn manages to decode it by poetic thought. That decoded poetic word reaches the consciousness of man and converts it into a verbal word, which is the word with which man is able to communicate. By being capable of communicating his being, man has already been created as a unit, since he is capable of uniting his Consciousness with his Being.

If we use a small child as an example, the child wants, loves, feels pain, but is not aware of it (because he has the being, but has not yet developed consciousness) until little by little, he becomes aware of it. He realizes what each thing is and manages to decipher it (when his consciousness develops and he manages to decode his being).

The method. Poetic-reason

A method is a path, a path along which one begins to walk. The curious thing here is that the discovery of this path is not different from the action itself that has to lead to the fulfillment of the person who performs it. The characteristic of man is to open the way, says Zambrano, because in doing so he puts his being into exercise; man himself is the way.

The ethical action par excellence is to open the way, and this means providing a mode of visibility, since what is properly human is not so much to see as to give to see, to establish the framework through which vision —a certain vision— is possible. Ethical action, then, along with knowledge, since by drawing the frame a horizon opens up, and the horizon, when it clears up, provides a space for visibility.

It can be said that the thought of María Zambrano is an «oriental» philosophy in the sense in which the Persian mystics used the term: as a type of knowledge that originates to the east of Intelligence, there where the sun or light he wake up. A philosophy therefore that deals with inner vision, a philosophy of dawn light. And intelligible light is, clearly in Zambrano, the dawn of consciousness, which does not always have to be that of reason, or not only, or not entirely, since reason will have to be assisted by the heart in order for it to be present. the entire person. The vision depends, effectively, on the presence, and who has to be present is the subject, consciousness and united will.

The poetic-reason, the method, begins as auroral knowledge: poetic vision, attention ready to receive, to the unveiling vision. The attention, the vigilant attention, no longer rejects what comes from outer space, but remains open, simply willing. In its nascent state, poetic-reason is dawn, unveiling of forms before the word. Later, the reason will act revealing; the word will be applied in the outline of the symbols and beyond, where the symbol loses its mundane consistency, maintaining only its link character. It is then that poetic-reason will fully occur, as a metaphorical action, essentially creator of realities and above all of the first reality: that of the person himself who acts by transcending, losing himself and gaining being in the return of his characters..

Reason, then, but synthetic reason that is not immobilized in arborescent analysis and deductions; reason that acquires its weight, its measure and its justification (its justice: its balance) in its activity, following the rhythm of the beating, the inner drive itself. This type of reason, which Zambrano has not hesitated to call "method" does not aspire to establish any closed system. It aspires — aspiration that comes from the soul or breath of life — to open a place that widens like a clearing in the middle of the forest, that forest of which the spirit-body consists of the one who is fulfilled in/with the method.

Poetic-reason, essentially metaphorical, approaches without hardly forcing the pace, to the place where vision is not yet informed by concepts or judgments. Rhythmically, the metaphorical action traces a comprehensive network that will be the area where reason builds poetically. Reality will then have to be presented reticularly, since this is the only possible order for a reason that seeks maximum breadth and minimum violence.

Truth, reality and language

The idea of poetic knowledge or poetic reason carries with it a certain way of conceiving truth, reality and language. There are various perspectives that have been raised about these concepts.

The reality that is presented when knowing poetic is that background in which resides the enigmatic, the mysterious, the sacred. «Reality», as María Zambrano has written, «is presented to the man who has not doubted [...] it is something prior to things, it is an irradiation of life that emanates from a depth of mystery; it is the hidden, hidden reality; corresponding in short to what we call sacred today» (Man and the divine).

The word reality, in the context of poetic knowledge, points to everything that the human being poetically experiences as fundamental (life, being), and that is why Zambrano resorts to metaphors such as the root, the heart, etc..

María Zambrano's thought is truly philosophical, metaphysical thought, but to the extent that it is located on the border of what is accessible to discursive reason, it is a thought that is close to mystical.

Now, reality is only accessible in the non-violent attitude, if not "pious" and receptive of the one who knows how to wait, listen and welcome. Hence, the truth is understood as a gift that is received "passively", and fundamentally as a revelation.

This truth is not revealed or manifested in any form of language, but in the poetic word. This is not the word that serves as an instrument of domination, that names and defines things in order to dominate and seize them. Nor is it considered an instrument of communication.

In the authentic word, more than communication, there is "communion" between those who listen and understand it. In Claros del bosque (her most important work, perhaps the most suggestive of all), this philosopher points out that «the word not intended for consumption is what constitutes us: the word we do not speak, the that speaks in us and we, sometimes, translate into saying».

All these reflections by María Zambrano aim to establish a «poetic thought», a thought capable of overcoming the abyss between philosophy and poetry (this is Zambrano's great concern). Precisely this attempt makes two different levels seem to be confused in her discourse:

- The level of philosophical reflection on the insufficiency of rationalism is a philosophical discourse.

- The level of "translation by saying" is philosophical and of a mystical-poetic character. This duality of planes is perhaps what makes the reading of his work more interesting Of the forest.

Work

- Horizon of Liberalism (1930, Morata Editions, reissued in 1996 by the same editorial with introductory study by Jesus Moreno Sanz)

- Towards a knowledge of the soul (1934)

- Philosophy and Poetry (1939)

- The Living Thought of Séneca (1941)

- Towards a knowledge of the soul (1950)

- Delirium and destination (written in 1953 and published in 1989)

- Man and the Divine (1.a edition: 1955. 2.a, increased: 1973)

- Person and Democracy: A sacrificial History (1958, reissued in 1988)

- Spain, dream and truth (1965)

- Dreams and time (reissued in 1998)

- The Creator Dream (1965)

- Of the forest (1977)

- The Tomb of Antigone(1967) (Mondadori Spain, 1989)

- From the aurora (1986)

- The rest of the light (1986)

- The blessed (1979)

- For a history of piety (1989)

- Unamuno (written in 1940 and published in 2003)

- Letters from the Pièce. Correspondence with Agustín Andreu (written in the 1970s and published in 2002)

- Confession, literary gender and method (Luminar: Mexico, 1943; Mondadori: Madrid 1988 and Siruela: Madrid, 1995).

Complete Works

At the end of 2011 the publication of his complete works began under the responsibility of Galaxia Gutenberg/Círculo de lectores, compiling his published books, articles not published in books and the many unpublished ones preserved in the Archive of the María Zambrano Foundation in Vélez-Málaga. In total there will be eight volumes that make it up.

- Zambrano, Mary (2011-). Complete works. Eight volumes. Jesus Moreno Edition. Gutenberg Galaxy/Reader Circle.

- Volume I: Books (1930-1939). 2015. ISBN 978-84-16252-41-1.

- Volume II: Books (1940-1950). 2016. ISBN 978-84-16495-49-8.

- Volume III: Books (1955-1973). 2011. ISBN 978-84-8109-953-9.

- Volume IV: Books (1977-1990).

- Take 1. 2018. ISBN 978-84-15472-88-9.

- Volume 2. 2019. ISBN 978-84-17355-26-5.

- Volume V: Articles and unpublished (1928-1990). (In preparation)

- Volume VI: Autobiographical Writings (1928-1990). 2014. ISBN 978-84-15863-84-7.

- Volume VII: Articles and unpublished (1951-1973). (In preparation)

- Volume VIII: Articles and Unpublished (1974-1990). (In preparation)

Typecasting

The work of María Zambrano, ignored for much of her life, has been progressively recognized and attached to different groups, tendencies and generations. The author herself denies in her work and in her correspondence that cultural policy of factions, slogans and pigeonholes.

Nevertheless, here is a reference to the attempts to frame the work and person of Zambrano in the Generation of 1998, 1927 and 1936, the latter in which, as Ricardo Gullón indicates, due to his age and the The friendship he had with Miguel Hernández and Luis Cernuda would theoretically be reunited.

Acknowledgments

In July 2018, the Association “Herstóricas. History, Women and Gender” and the “Comic Authors” Collective created a project of a cultural and educational nature to make visible the historical contribution of women in society and reflect on their consistent absence in a card game. One of these letters is dedicated to Zambrano. In the town of Vélez Málaga there is a park dedicated in her honor, the María Zambrano park. It was inaugurated on December 4, 2003 and is the largest green space in the town. Also in this town is the María Zambrano Foundation, with its headquarters in the Beniel Palace.

In 2004, coinciding with the centenary of her birth, she was recognized as Author of the Year in Andalusia and, for this reason, the Andalusian Center for Literature organized different outreach activities around her figure and her work, among others the traveling exhibition 'María Zambrano: the dawn of thought'. That same institution published a Brief Anthology by Professor Juan Fernando Ortega Muñoz and, more recently, has published the María Zambrano Didactic Notebook, the work of María Luisa Maillard, for distribution in educational centers.

In the city of Málaga, the Málaga-María Zambrano Station bears her name. It was inaugurated on November 28, 2008. It has 7 platforms and 11 tracks, with metro, suburban and high-speed train connections.

The philology library of the Complutense University of Madrid also bears her name, a space that is located halfway between the Faculty of History and the Faculty of Philosophy and Philology (formerly the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters) where she herself studied.

The Maritime Safety and Rescue Society owns a ship called María Zambrano (BS-22).

From October 19, 2022 to January 15, 2023, the Teatro Fernán Gómez Cultural Center of the Villa organized an exhibition curated by Tània Balló on Las Sin Sombrero, to make visible that, within the group of 27, there was also a generation of women painters, poets, novelists, illustrators, sculptors, thinkers, filmmakers and composers who enjoyed national and international success in their time, and among whom Zambrano is recognized.

Some dictations and sentences

- The attitude of asking implies the appearance of consciousness.

- The question, which is the awakening of man.

- The word of poetry will always tremble on silence and only the orbit of a rhythm can sustain it.

- Philosophical is the question and poetic finding.

- Philosophy is a preparation for death and the philosopher the man who is ripe for it.

- Earth manages everything, it distributes everything. Well, I mean these things, if they leave her. But they don't leave her, no. They never leave her, those who command. Will you ever let her do her work in peace?

- Who has unity, has everything.

| Predecessor: - | 1st Prince of Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities 1981 | Successor: Mario Bunge |

| Predecessor: Carlos Fuentes | Miguel de Cervantes Award 1988 | Successor: Augusto Roa Bastos |

Contenido relacionado

Marguerite Yourcenar

Aware

Metaphysics