Manuel Azana

Manuel Azaña Díaz (Alcalá de Henares, January 10, 1880-Montauban, November 3, 1940) was a Spanish politician, writer and journalist, president of the Council of Ministers (1931-1933) and president of the Second Republic (1936-1939). He stood out for the reforms that he implemented during his government, the so-called social-azana biennium, and for his role as head of the Republican side during the Spanish civil war. [ citation needed ]

Belonging to the Alcalá middle class, he came from a liberal family and had a religious upbringing, factors that would form his republican, leftist and anti-clerical thought. After graduating in Law, Azaña began to get involved in the cultural and political life of the Restoration, advocating for greater economic freedoms and rights for workers, as well as collaborating in the Ateneo de Madrid, of which he would be president. A firm opponent of the generation of '98, he is framed as an author within the generation of '14. He collaborates with intellectuals such as José Ortega y Gasset in projects to reform Spanish political life and joins the Reformist Party. During the First World War, Azaña displayed an allied sentiment, and worked as a war correspondent in France and Italy. After several unsuccessful literary and electoral projects, he created Acción Republicana in 1926, during the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. That same year he was awarded the National Literature Award for his biography Vida de Don Juan Valera . Azaña was one of the signatories of the San Sebastián pact in 1930, a fact that ended up solidifying republicanism as a political alternative. The conflicts of the Restoration culminated after the municipal elections of April 1931 with the abdication of Alfonso XIII and the proclamation of the Second Republic, whose government Azaña would preside over for a few months on a provisional basis.

Being elected President of the Government in the general elections of 1931, he carried out educational, economic, military, social and structural reforms, among which the agrarian reform, the military reform, the creation of an autonomy statute for Catalonia stand out, and the secularization of the State. The controversial nature of his reforms, in conjunction with the Sanjurjada and the events in Casas Viejas, led to his resignation in September 1933. Despite being arrested after the 1934 revolution, without being accused of any crime, Azaña returned to political life refounding his party in the Republican Left, which will form part of the Popular Front in the 1936 elections. These return Azaña to the presidency of the Government, to later be invested as president of the Republic, replacing Niceto Alcalá-Zamora, with Santiago Casares Quiroga at the head of Government. After a few months, there is a military uprising whose failure starts the Spanish civil war. In this period, the role of Azaña is notoriously reduced before the authority that the war context propitiates to the anarchist militias and the Communist Party. He sought Franco-British intervention in the conflict and a national reconciliation, demanded in his speech Peace, Mercy and Pardon in 1938.

Once the French government opened the way for civilians and soldiers across the border, in January and February 1939, Azaña, his family and his collaborators headed towards it. On February 4, Negrín personally informed him that it was the government's decision that he take refuge in the Spanish embassy in Paris until he could organize his return to Madrid. Azaña, however, made it clear that, after the war, there was no possible return to Spain. On the 12th General Rojo presented him with his resignation and on the 18th Negrín sent him a telegram urging him that, as president, he should return to Spain. Azaña, however, was clear that he was not going to return, as he was clear that he would present his resignation as soon as France and the United Kingdom recognized Franco's government, which happened on February 27. From France, Azaña sent the letter of resignation to the president of the Cortes on February 28. On March 31, at a meeting of the Permanent Deputation of the Congress of Deputies in Paris, Negrín strongly criticized Azaña's decision not to return to Spain.

Biography

Childhood and adolescence

Manuel Azaña was born into a family with a solid financial position and a presence in the political and intellectual life of Alcalá. The full name with which he was registered in the civil registry was "Manuel María Nicanor Federico Azaña Díaz-Gallo". However, years later he was corrected at the request of his grandmother, so that the surname "Gallo" would disappear, considering that said historic lineage had been dishonored for being associated with republicanism. His father was Esteban Azaña Catarinéu, an owner, and his mother, María Josefina Díaz-Gallo Muguruza, a housewife. His father, from a family of notaries and City Hall secretaries, was also involved in politics and became mayor of the city; he wrote and published in 1882 and 1883 a History of Alcalá de Henares in two volumes. As for his mother's family, an old and notorious noble house that was dedicated to commerce, it came from the Burgos town of Escalada. His name, Manuel, was that of his maternal grandfather Manuel Díaz-Gallo (whose birth names They were Díaz and Gallo-Alcántara, a relative who was of the Count of Liniers), married to María Josefa Muguruza, his maternal grandmother. His paternal grandparents were Gregorio Azaña and Concepción Catarinéu. The best man at his parents' wedding was Antonio Cánovas del Castillo.

Manuel was the second of four siblings (Gregorio, Josefa and Carlos were the others). In addition to his parents, and especially after their premature death, his maternal uncle Félix Díaz-Gallo played an important role as protectors during his childhood, with a certain intellectual influence over Manuel, and his paternal grandmother, Conception Catarineu.

He studied at the Colegio Complutense de San Justo y Pastor until high school, which would begin in the academic year 1888-1889, taking the exams at the Instituto Cardenal Cisneros, in Madrid. He was a student with excellent grades, with the A predominating among his grades, although he would eventually complete his bachelor's studies with a passing grade.

On July 24, 1889, his mother died; a few months later, on January 10, 1890, his father. Manuel and his brothers went to live at the house of his paternal grandmother, Concepción. There, with a constant feeling of loneliness, he would carry out his first readings of him, thanks to the different books accumulated by his grandfather Gregorio de él:

Always, every time he evokes his childhood, the same metaphor: Manuel Azaña is remembered in the days of his childhood and adolescence, especially as a book devourer.

By his grandmother's decision, Manuel completed his higher studies in Internal Law at the recently created María Cristina de El Escorial Royal University College. Since the school lacked the power to issue bachelor's degrees, students had to take the exam for free at the University of Zaragoza.

After three courses (preparatory and the first two Law courses), during the 1896-1897 academic year he suffered a religious crisis that led him to drop out of school, continuing his studies at home:

It was not hostility, nor resentment, nor some sort of "unselfish rebelief", as some friar has dictated, confusing the feelings of a young man of sixteen years who one day says he does not want to confess to those of a militant atheist: it was simply that religion, in all the dimensions in which he had lived as a child and a teenager, stopped making sense for him.

During the academic year 1897-1898, he edited the magazine Brisas del Henares with some friends, in which he published various local chronicles.

On July 3, 1898, at the University of Zaragoza, he passed the Licenciatura en Derecho degree exam with the grade of outstanding.

Youth

He settled in Madrid in October 1898, with a view to preparing the doctoral course at the Central University. At the time, and thanks to the efforts of his uncle, he began to work as an intern in the law firm of Luis Díaz Cobeña, where he coincided with Niceto Alcalá Zamora.

In February 1900, he applied for admission to the undergraduate exercises and presented his thesis, entitled The Responsibility of Crowds, on April 3, obtaining the title of Doctor of Laws with the qualification of outstanding. In his thesis, Azana

He stated that when he acts in multitude, the individual is responsible for his actions and recognized that when the crowds raise their voices threatening to disturb the order is to claim something that is almost always due to them in justice.

During that time, his readings basically focused on works related to social issues, socialism and the history of France and England.

Since October 1899, he was a member of the Academy of Jurisprudence, where he actively participated in various debates. In January 1902, he read his report on Freedom of Association, in which he addressed the need for religious orders and congregations to be regulated by the State, and appealed for respect for freedom of education for the Catholic associations formed for that purpose. In other interventions, regarding reports presented by different partners, Azaña expressed ideas such as that what was decisive in choosing a government system was the degree of acceptance of it, whether it was a monarchy or a republic, and the existence of principles such as respect for equality among citizens, universal suffrage, national sovereignty and representative institutions. In another case, he appealed to the need for the law to establish a reform that would introduce a true freedom of the market, with the recognition of the freedom of association of the proletariat.

Towards the end of 1900, Azaña also entered the Ateneo de Madrid, where he frequently expressed his critical attitude both towards the generation of '98 and towards regenerationism. Regarding the importance that this institution would have in his life, Giménez Caballero wrote in 1932:

Azaña became the Ateneo, and the Ateneo, Azaña. Azaña would not understand without Alcalá and without El Escorial. But much less without the Athenaeum. Alcalá and El Escorial formed his character. The Athenaeum was the pretext to exercise it, the divinity to which to offer it.

On the other hand, from February 1901 he began to collaborate, with literary texts and theater critics, in the magazine Gente Vieja, signing with the pseudonym Salvador Rodrigo, which he had already used in his teens.

However, unexpectedly, in 1903 he returned to Alcalá to take charge of the family businesses with his brother Gregorio: a farm, a brick and tile factory, and the Complutense Power Plant. Simultaneously, he resumed his literary activity concentrating on the writing of an autobiographical novel, The vocation of Jerónimo Garcés . He also returned to journalistic work through a local magazine, La Avispa , founded by his brother Gregorio and some of his friends.

But the failure of the family businesses led him to return to Madrid and request to take part in 1909 in the exercises of the opposition to Third Party Assistants of the General Directorate of Registries and Notaries. In June 1910 he appeared as number one on the list of results, being proposed for the corresponding position. After various natural promotions within the ranks, in 1929 he was appointed Second-class Section Chief Officer of the Technical Body of Lawyers of the Ministry of Grace and Justice, with an annual salary of 11,000 pesetas.

Parallel to his work as a civil servant, Azaña continued to carry out intellectual work. Thus, in 1911 he delivered his first political conference at the Casa del Pueblo in Alcalá de Henares. In it, he faced the fashionable subject, the Spanish problem , but instead of focusing on the solution that most of the intellectuals proposed in this regard, the school, Azaña showed his concern for the state. Thus, in his conference he affirmed that

the "problem of Spain" consists of democratically organizing your state, the only medicine to end the "apartment of the cultural life of Europe" (...). [And that] to achieve this, it is indispensable to release him from the social powers that mediate him (...) through the political action of citizens aware of his duties.

That same year, in two articles published in La Correspondencia de España, Azaña insisted, critically confronting Pío Baroja's generation, on the need for an active political attitude > by the citizens to face the solution to the problem in Spain with guarantees.

With the intention of taking French civil law courses at the University of Paris, he applied to the JAE for a six-month pension, which was accepted at the end of September 1911. On November 24, he arrived in Paris and there, until his departure a year later, he developed an intense intellectual activity of which he left testimony, in addition to personal notes, in various articles sent under the pseudonym Martín Piñol to La Correspondence from Spain. Azana was especially impressed by

the vision of Paris as the unique work of civilization that has known to bring together (...) the Christian heritage with the rehabilitation of reason.

In other articles, he addressed the importance of rehabilitating the functionality of parliaments as guarantors of national security and the concept of homeland, which Azaña associated with culture and with justice and freedom aimed at a common good.

In Paris, in addition to various readings and cultural visits to churches and monuments, he attended political rallies and multiple conferences on various topics, including some dedicated to the history of religions by Alfred Loisy and others on psychiatry given by Henri Piéron.

He met and became friends with Luis de Hoyos, with whose fifteen-year-old daughter Mercedes he fell in love with.

After a few days in September in Belgium, he returned to Spain on October 28, 1912.

In February 1913 he became part of the Ateneo's board of directors as first secretary; the advanced age and the great activity of the president, Rafael María de Labra, led Azaña to have to assume some of his functions, especially since 1916. In addition to revitalizing his library, Azaña managed to clarify certain economic questions that plagued the institution.

Simultaneously, in addition to receiving German classes, he began to take seriously the idea of writing a study on the literature caused by the disaster of 98, for which he studied the centuries of the Late Middle Ages, in search of an explanation of Spanish decadence, and engaged in a critical and controversial dialogue with the intellectuals who had addressed the question of that mess. As a consequence of these investigations, Azaña developed a personal concept of patria in which he denies its medieval existence (although, paradoxically, he was looking for his true parents during that period) and which he identifies with "the equality of citizens before the law; that is, it is democratic."

At that time, his friendship with Cipriano de Rivas Cherif was definitively consolidated.

Maturity and beginnings of his political activity

In mid-October 1913, together with other young people from the new intellectual generation in Spain and the company of José Ortega y Gasset, he endorsed with his signature, the first, a so-called «Prospectus of the Political Education League of Spain », who cried out for:

the organization of a minority in charge of the political education of the masses, linking the fate of Spain to the advance of liberalism and the project of nationalization, [and] grouping with the purpose of exercising some kind of political action that would open, without leaving the monarchy, the doors to democracy.

Politically, the manifesto implied explicit support for the Reformist Party chaired by Melquíades Álvarez, to which many of them, including Azaña, immediately joined.

In his first speech as a member, in December 1913, Azaña vindicated, once again, parliamentary democracy, the need for a secular and sovereign State, attentive to social justice and culture, and the imperative need to end with caciquismo; for the rest, he rejected the possibility that his party could undertake such an undertaking with the help of socialists, republicans or liberals.

Despite his desire to present himself as a candidate for the district of Alcalá in the elections of March 8, 1914, in the end he did not do so, as he estimated that he could cause problems in his town due to the existing political division. For the rest, the bad electoral results of the party and the presence in it of a greater percentage of intellectuals than politicians, ended up making the formation languish for a while, while the debate on whether the formation should come closer to the Liberal Party was consolidated. of the count of Romanones, something that Azaña rejected outright.

The beginning of the First World War led Azaña to position himself in favor of the allies and to develop some moral support activities for them. He made the gallery of the Ateneo available to various French intellectuals, endorsed a «Manifesto of Adhesion to the Allied Nations» (published in Spain on July 9, 1915) and in October 1916 he paid a visit to France with a group of Spanish intellectuals, which included an approach to the front. Along with his admiration for the civic force shown by the French during the war, Azaña also expressed his rejection, far from any myth, of the horrors caused by it.

The controversy between pro-allies and Germanophiles, permanent throughout the conflict, intensified when the former decided to explicitly criticize the latter. Thus, the same weekly España published a manifesto written by a so-called Anti-Germanophile League, which Azaña signed. As an intellectual support for the movement, he also gave a conference at the Ateneo with the title of «Los motivos de la germanofilia», where he stressed the idea that the neutrality of Spain in the Great War had as a real reason the country's lack of military means; otherwise, explaining the courageous resistance of the French, he reiterated his principle that patriotism was directly linked to civic virtue, the ideal motive of citizens as members of a political society.

In September 1917, Azaña made a trip to Italy together with Unamuno, Américo Castro and Santiago Rusiñol to visit the war fronts; in November of that same year, he traveled to France again with the same objective.

On his return, and from January 1918, he began a series of lectures at the Ateneo on «The military policy of the French Republic», a topic that had been occupying him for a long time and that, finally, would end up materializing in a project of work in three volumes on France of which only the first would be published, precisely on that military issue.

Azaña's thesis was that

modern society is based on a contract in which individuals agree to alienate part of their freedom for the formation of the collectivity; the National Army is one of the institutions that update that covenant, and the one that most seriously does so. In defense of the nation, citizens, without distinction of classes, must be willing to give not a few years of their lives, but their entire life if necessary.

For the rest, Azaña understood that the modern State creates the nation, but, at the same time, as a system opposed to the characteristic of pre-modern societies, it also creates the individual, endowed with inalienable rights that allow him, in turn, to defend himself of the State.

As a consequence of this dedication to the military issue, he was in charge in the Reformist Party of developing the ideological part of it on War and Navy; Basically, Azaña proposed moving the army away from politics, reducing the number of officers or, at least, preventing its growth, and reducing the length of military service.

At the same time, he maintained his incipient interest in politics and ran as a candidate in the general elections on February 24 for the district of El Puente del Arzobispo; Assuming the need for unity, he appealed to the union of the left in his talks with citizens and insisted on transmitting his idea of homeland as quality of free men . Also, in these first rallies, he made his first direct attacks on the Crown and some first references to the possibility of a revolution, by force if necessary, to change the status quo of Spanish reality. He got 4,139 votes, which were not enough to make him a deputy.

In May 1919, in a meeting called by the Reformist Party to denounce the delivery of the decree of dissolution of the Cortes to the government of Antonio Maura, Azaña participated with a speech in which he spoke of the collapse of his liberal hopes, associating liberalism with the rights of workers as individuals. The rally definitively distanced the reformists from any hope of reforming the established regime and brought them closer to the left, especially to the demands of the socialists.

Simultaneously to the above, together with several republican, socialist and reformist intellectuals, he participated in the creation of the Spanish Democratic Union for the League of the Free League of Nations, which demanded a full democracy for Spain. The good relations between the politicians of these factions were further consolidated with a series of conferences (entitled "The current political moment") that, on the occasion of the Spanish political crisis of the late 1920s, were held at the Ateneo from April of 1919.

Between October 1919 and April 1920, he lived in Paris with his friend Rivas Cherif, and worked as a special envoy for the newspaper El Fígaro sending articles on the political situation in France after the war and on criticism of that war.

At the beginning of the year, he broke his relations with the Ateneo resigning as secretary, in what would be an indication of some new intellectual concerns that would materialize with the foundation, together with Rivas Cherif, of a literary magazine that would have the patronage of the architect Amós Salvador. Thus, in June 1920 La Pluma, Literary Magazine hit the streets. Azaña, in his collaborations, played the most varied registers, from the melodrama to literary criticism, passing through the political essay.

In 1923 he was commissioned to revive the magazine España, for which they had to sacrifice La Pluma. Azaña increased his political collaboration and reflected his impressions on the paths of the Reformist Party, which in December 1922 had installed one of its members, José Manuel Pedregal, as Minister of Finance, and more insistently directed his criticism of the dependency of the government military and church.

In April 1923, he repeated his candidacy for Congress for the district of El Puente del Arzobispo, obtaining similar results to the previous time.

The reaction to the coup d'état by Primo de Rivera

Miguel Primo de Rivera's coup was a critical moment in his political evolution. In the first place, he led him to break with the Reformist Party because he understood that its doctrinal and moral foundation was insufficient to deal with the political situation in Spain. Basically, Azaña understood that the party had been founded to democratize the monarchy, preserving its form and its historical prestige, but in no way its inherent arbitrariness, so that its acceptance of the coup could be considered a simply unforgivable betrayal and a failure in the line of the party that failed to see the impossibility of trusting the monarchy. Derived from the above, secondly, Azaña also broke with the monarchy. And thirdly, he definitively moved away from many of the figures of 1998 and regenerationism, who took the Dictatorship as an opportunity to break with the previous regime, something that was unthinkable for Azaña.

As a consequence of all this, Azaña ended up identifying democracy with the republic and postulated the union of republicans and socialists as the basis for trying to achieve it. Thus, he summoned Julián Besteiro and Fernando de los Ríos to symbolize this new movement of political action.

capable of opposing the overwhelming bloc of the collated obscurantist forces, the first resistance, the counter-offensive after, of the latent liberal will so the well-known resignation of the country.

When the magazine España was closed due to censorship, in May 1924 he finished writing a manifesto entitled Appeal to the Republic which, finally, after numerous refusals from friends and colleagues to facilitate its distribution, it was published clandestinely in La Coruña. The core of the manifesto was the idea that monarchy was the same as absolutism, and that democracy was only possible in the republic; for the rest, it opened the doors to a great political alliance in which the members should only confirm their acceptance of the above, that is, they should only recognize its liberal essence in the most elementary sense of the term: the individual as a subject of rights and the nation as a framework where the free man fulfills his destinies. Azaña devised, then, a republican action in which the proletariat and the liberal bourgeoisie would go hand in hand. The manifesto did not have large supporters.

Annulled any possible initiative for the control of the dictatorship, Azaña took refuge in his love of writing and began to participate in a kind of clandestine gathering that was held in the laboratory that the pharmacist José Giral had on Atocha street in Madrid. There he began to work more actively in the preparation of the republic, something that materialized in a new manifesto written in May 1925. Ideologically, this manifesto reiterated what was said in the Appeal, but incorporated the novelty that it was conformed as the germ or the materialization of a political group constituted at the end of 1925 by the members of that gathering that was called, in principle, Republican Action Group or Group of Political Action. The denomination responded to the desire not to be confused with the traditional political parties and to open the way as a possible point of union between them, according to the idea of a liberal alliance enunciated by Azaña in his manifestos. In this sense, one of his first approaches was made to the Radical Republican Party of Alejandro Lerroux. This is how the Alianza Republicana platform emerged, which also included the Federal Republican Party, represented by Manuel Hilario Ayuso, and the Partit Republicà Català (Catalan Republican Party) represented by Marcelino Domingo.

On the occasion of the celebration of the anniversary of the First Republic, February 11, 1926 marked the official beginning of the activities of the Republican Alliance. In his "Manifesto to the country", he presented himself as a point of articulation for republicanism; In addition, it demanded a federative organization of the State, attention to education, agrarian reform measures and social legislation, etc.

However, the dictatorship, reinforced by the calm in Morocco, annulled any public initiative of a political nature. Around 1926 relations with Lerroux were fixed and Azaña participated in the latter's house in the meetings of the Alianza interim board; Also, on several occasions he became involved in military insurrection projects against the dictatorship.

Azaña frequently had to take refuge in his activity as a writer. In 1926 he was awarded a National Literature Prize for his Vida de don Juan Valera , which he would not publish. He also returned to his reflection on the relationship between the ideas of the group of '98 and the dictatorship, and subjected Ángel Ganivet's Spanish Idearium to strong criticism. Likewise, he submitted to analysis the revolution of the commoners, in which he saw a precedent of the revolutions of the third estate, which would remain since then in confrontation with the monarchy and the nobility. In this way, he reinforced his idea of the need for political union between the bourgeoisie and the working class so that, already disillusioned by the possible evolution, he would resume the old idea discarded in the past that the path was the revolution that ended the power of the alliance between the Crown and the oligarchy.

In 1927 he published The Friars' Garden, a narrative with autobiographical components, which was well received by critics in general. The drama that he describes in it is that of the constitution of the individual, in which the teaching received is subjected to a very strong criticism. She also dedicated herself with special interest to the theater, representing her play La Corona in 1928.

As for his private life, on February 27, 1929, he married María Dolores de Rivas Cherif in San Jerónimo el Real in Madrid.

Republican Leadership

In January 1930, the withdrawal of Primo de Rivera caused a revulsion in the situation, causing the republican sentiment to reactivate. Thus, on February 8, the Republican Action Group was presented publicly and Azaña resumed his idea of a great coalition of political forces united by his pro-republic attitude. And he stressed that the republic

He will undoubtedly cover all the Spaniards; he will offer them all justice and freedom; but he will not be a monarchy without a king: he will have to be a republican republic, thought by the Republicans, governed and directed according to the will of the Republicans.

Simultaneously, Azaña also had to address the Catalan problem; From his point of view, although he did not conceive of a separation, he recognized that, if Catalonia wanted to separate from Spain, it would have to be allowed.

In June he took over the presidency of the Ateneo, and put it at the service of the republican mobilization, in which he was fully involved with the immediate objective of achieving a united front. Thus, he first achieved a pact between the Alianza and the Radical Socialist Party, and shortly after another with the Radical Socialist and Federal parties and the Galician Republican Federation. At the same time, under the auspices of Miguel Maura, they managed to form a Republican Liberal Right with young ex-monarchists.

On Sunday, September 28, 1930, a massive Republican meeting was held in the Las Ventas bullring in Madrid. Among others, Azaña spoke, greeting those present as a manifestation of the national will and identifying them with some spontaneous Cortes of the popular revolution, repeating his old idea of the importance of individuals in the conformation of the Republic and insisting on the inescapability of the popular revolution to achieve a change in the status quo:

Let us be men, determined to conquer the rank of citizens or to perish in the endeavor. And one day you will rise to this cry that sums up my thought: Down with the tyrants!

Finally, the Republican Alliance was constituted, with the presence of the radicals of Lerroux and those of Acción azañista. In October, the Socialists were invited to join the alliance, who were divided on the matter between opponents such as Besteiro, and those in favor such as Largo Caballero. With an immediate insurrection in mind, Azaña and Alcalá-Zamora asked them that the working people accompany the army as soon as the uprising occurred, so that the military, the people and the middle class were its protagonists, and not only the army. The Socialists accepted in exchange for two positions in the revolutionary committee of the Alliance.

In subsequent meetings, it was decided that for the day of the uprising a general strike would be declared in all of Spain, a manifesto was prepared that would have to be disseminated previously, calling for the revolution (justified by them as the state of Spain was of tyranny) and the Provisional Government that was to assume power was designed, in which Azaña would be in charge of the Ministry of War.

On December 15, 1930, the projected day for the insurrection, events went awry and the main Republican leaders were arrested. Azaña managed to hide at his father-in-law's house, where for almost a month he dedicated himself to writing his novel Fresdeval, in which he tells the story of his family in Alcalá de Henares in the XIX and exposes his criticism of the liberals for not having known how to take advantage of the War of Independence to found the nation.

The Second Spanish Republic and the Civil War

The proclamation of the Second Republic

Still in hiding, Azaña continued to monitor the development of events. He tried to support the validity, even provisional, of the government designed on December 15 and, already on the eve of the municipal elections that would precipitate everything, he granted the meaning of a plebiscite to these and advanced the possibility of a manifestation of the popular will that, without the impediment of the army would constitute a kind of "national uprising". Finally, on April 12, 1931, the Republican-Socialist coalition triumphed in the municipal elections in the capitals and main towns. Given the enthusiasm of the population in Madrid, who went out into the streets, Azaña was picked up from the house where he was hiding by his companions and went with them to Puerta del Sol, to later look out on the balcony of the Ministry of the Governorate.

That same night, accompanied by artillery captain Arturo Menéndez, he appeared at the Buenavista Palace, where he met the undersecretary of the Ministry of the Army, General Enrique Ruiz-Fornells. He took charge of the Ministry and thus communicated it to all the military garrisons, to which he asked for patriotism and discipline; Subsequently, by decree, he established the obligation of all members of the military establishment to promise their adherence and fidelity to the Republic, rendering the fact null and void to the institutions that were already defunct at that time. With the decree known as the withdrawals or Azaña law , he began a process of reducing military forces. In general, the intelligentsia praised these measures, but they caused discomfort in high military hierarchies.

As a consequence of the arrival of the Republic, and with a view to the imminent Constituent Cortes elections, the Republican Action Group became a political party, deciding on a leftist orientation. Throughout their first National Assembly, held at the end of May, they outlined their political program, taking great care to maintain an intermediate position between the Socialists and Lerroux's radicals. At the inaugural meeting of the campaign, in Valencia in June, Azaña reiterated the objective of radically breaking with the past and rebuilding the country and the State, for which it was necessary to crush the caciquismo.

In the June 28 elections, Acción Republicana won 21 deputies. His consequent maneuver was to try not to be subordinated to Lerroux or break with the Socialists, reinforcing the Alliance and maintaining a leftist position for his party, which would be fully defined in its second National Assembly, held in September, with Azaña remaining as president. There, in the closing speech, he stressed the need for the Republic to penetrate all the organs of the State, and explicitly pointed to the educational sphere, specifically the schools controlled by religious orders.

One of the critical moments in the elaboration of the draft Constitution dealt with this matter, when article 24 (later it would be 26) was discussed. In principle, in addition to sanctioning the submission of religions, as associations, to the State, the article established the dissolution of religious congregations and the nationalization of all their assets. Both the Catholic hierarchy and several politicians, among them Alcalá Zamora (President of the Republic), reacted negatively, which made it necessary to reformulate the article so as not to block the formation of the government. Azaña, fearing that both Alcalá Zamora and Maura, and even Lerroux, would disassociate themselves from the government, leaving it exclusively in the hands of the left, decided to support this new wording, in which the most conflictive elements were softened: they would dissolve only orders with a special vow of obedience to an authority that was not the State (the Jesuits) and the exercise of education, industry and commerce would be prohibited for the rest.

On October 13, he had to deliver a speech in congress in order to make the most leftists reflect on the advisability of accepting the new wording of the article. Not incorporating the dissolution of all religious orders focused on its fair terms what, in his words, was the so-called religious problem , since this

"it cannot exceed the limits of personal consciousness"; it is a political problem, a state constitution. It is a matter of organizing the State according to a premise that the proclamation of the Republic makes axiom: "Spain has ceased to be Catholic".

Thus, then, Azaña exposed his idea that the central trunk of Spanish culture was no longer Catholic, and that there was no going back. His idea was that this national religion had to be replaced by another of a secular nature. Hence, for Azaña it was enough to prohibit religious orders from teaching and to demand freedom of conscience for citizens.

From all of the above, it was derived the fact that between April and October Azaña had completely reformed the military and religious policy of Spain. The emotional impact of all those weeks on Azaña was summed up by himself with one sentence: he seemed to be witnessing what happens to another.

Otherwise, as the weeks progressed, the difficulty in forming a government made all eyes turn towards Azaña as a possible president. The vote in favor of the new article on the religious question led to the resignation of Alcalá Zamora. Maura, who had also resigned from the government, pointed out that there were only two possibilities for substitution: either Lerroux or Azaña. Lerroux rejected his candidacy and pointed out that Azaña was the ideal man, since he represented a minority party that could serve as a bridge between the majority.

President of the Government

He replaced, therefore, Niceto Alcalá-Zamora as president of the Second Provisional Government of the Second Spanish Republic (in October of the same 1931).

The immediate objectives were the approval of the Constitution and the budgets of the Republic, and the elaboration of the Agrarian Law. In addition, he carried out a Defense Law with the intention of endowing the government with extraordinary powers in case of need, and promulgated a decree to considerably reduce the staff of officials. Once the Constitution was approved, he recovered Alcalá Zamora for the presidency of the Republic, with which he incorporated the liberal Catholic right as a participating force in the direction of the country. In December, he got the Republican Alliance to definitively accept the coalition with the Socialists for the government, which led to the immediate withdrawal of Lerroux. Next, Azaña presented the resignation of the government to Alcalá Zamora and left the solution of the crisis in his hands. The President of the Republic, advised by Besteiro and Lerroux himself, once again entrusted the task of forming a government to Azaña, who in principle tried to repeat the previous balance of forces. However, Lerroux ended up refusing on the basis of his incompatibility with the Socialists, and with the probable intention that a government of that type could open the doors to the presidency of the same a few months later. Azaña once again put his position at the disposal of Alcalá Zamora, but he confirmed it in the same.

On December 17, he was finally able to present a program that turned out to be very ambitious, and which had as its most outstanding points the Agrarian Reform Law, the incorporation of unions into labor negotiations, the Confessions Law and Religious Congregations, the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia, an educational reform with the objective of universalizing primary education, the introduction of divorce, the reform of the Civil Code, the equalization of rights between men and women, ending the military reform, etc. He also had time to premiere his drama La Corona in Barcelona on December 19. He had to face two serious social problems at the beginning of 1932: a general strike called by the Federation of Land Workers (of the UGT) that resulted in several deaths, both by the Civil Guard and by demonstrators, and the proclamation of libertarian communism in the Llobregat basin. In both cases, he justified the use of military force as the only way, not to control the strikes, but to redirect an order that had been violently broken. In this sense, he set the limit of what can be assumed by the government in what is established by the Constitution.

On February 2, Azaña was initiated into Freemasonry, in an act (after which he would never step foot in a Masonic lodge again) of political intent aimed at facilitating his relations with the Radical Party (the Matritense Lodge, where the ceremony took place, he was lerrouxista) who began to strongly oppose his government. On the other hand, since the presidency of the government Azaña also had to face the development of at least three conspiracies against the Republic. In the first place, one promoted by the king, Alfonso XIII in order to return him to the throne; later, another carried out by monarchical elements attached to the infant Don Juan who sought the abdication of Alfonso; and, thirdly, one of a military type (simultaneous by the continuous complaints by commanders and army officers), led by generals Barrera and Cavalcanti, which would have been taking shape since mid-1931. Finally, on the night of the 9th On August 10, 1932, another conspiracy broke out, also led by General Barrera and accompanied on this occasion by General Sanjurjo, which Azaña managed to stop only with the help of the Civil Guard.

Although the coup was more complicated in Seville, the resolution favorable to the government ended up reinforcing it. Azaña, to seize the moment, made a trip that took him to numerous cities, including Barcelona, where he was received in September as the architect of the Statute of Autonomy in the smell of multitudes. However, he recalled, once again, that the destinies of Catalonia and Spain were united in the Republic.

Barely a year later, the winter of 1932 to 1933 marked the decline of Azaña's work as head of the government. The events in Casas Viejas, Castilblanco and Arnedo served as a pretext to support a political offensive by the center-right of Lerroux (which criticized the economic, social and political failure, and blamed part of the coalition with the Socialists) and the right of Miguel Maura, who would finally motivate the dismissal of Azaña, on September 8, 1933, by President Alcalá-Zamora. For the rest, in March of that year Catholicism had appeared as a political force under the name of the Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Rights, led by the young lawyer from Salamanca, José María Gil-Robles. Azaña and the Republican parties minimized their relevance and their ability to unite broad sectors of Spanish society, based on an idealistic concept of the Republic in which the people no longer belonged to anyone in particular The municipal results of April 23, 1933 gave this new right a decisive space in the Spanish political scene, in which the Republicans were increasingly disunited.

All in all, Azaña, even at the height of the criticism (February), maintained his positive assessment of his politics and his relationship with the socialists, whom he considered essential for the creation of what he called the new republican order; In particular, he strengthened his ties with Indalecio Prieto, with whom he had established not only a personal relationship, but "a complete agreement on strategies and political tactics." On June 8, in the midst of a crisis over the religious issue, and with most of the of the press and the intelligentsia against him, Azaña resigned, although he had to be entrusted again with the formation of the government. He tried to incorporate, once again, Lerroux's radicals, but Martínez Barrio prevented it by keeping Azaña the socialists in the government.

However, the new government did not last long: not only had relations between Alcalá-Zamora and Azaña been seriously damaged after the approval of the Confessions Law, but the division between socialists and republicans increased; Thus, the President of the Republic withdrew his confidence in Azaña on September 7 and entrusted Alejandro Lerroux with the task of forming a government.

In opposition

Acción Republicana contributed to it the figure of Claudio Sánchez Albornoz for the Ministry of State, a collaboration that the Socialists criticized to the point of causing their definitive break with the Republicans. Finally, as Lerroux did not obtain parliamentary support (after the debate that Azaña would call "of anger"), Alcalá-Zamora entrusted it to Martínez Barrio, who, after obtaining Lerroux's acceptance of the matter, presented on October 9 a concentration government with the presence of socialist politicians. On October 16, in the closing speech of the National Assembly of Republican Action, Azaña reaffirmed his policy carried out as president of the government and was proud of the revolution carried out in the right way. of various regime changes: political, family, religious, etc. With a view to the November elections, Azaña sought by all means a coalition with the Socialists, knowing that, otherwise, defeat would be inevitable against the right.

Indeed, on November 19, 1933, the coalition formed by the Radical Republican Party of Alejandro Lerroux and the Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Rights (CEDA) of José María Gil-Robles triumphed. Azaña kept his seat as deputy thanks to the fact that he had presented himself for the district of Indalecio Prieto (in Bilbao), who had maintained, against the slogans of his party, the coalition with the Republicans. On December 16, Lerroux became president of the government, with the support of Gil-Robles' CEDA, who made clear from the outset his future aspiration to govern. Azaña, in different public statements, was very critical of the CEDA's aspirations to govern, as long as they did not show their fidelity to the Republic, since he did not accept that, on the one hand, they seized power through votes and that, on the other, and according to him, they intended to put an end to the same system that had made it possible. In this sense, he clearly underlined the hierarchy of relevance for the State in the event of a critical situation:

above the Constitution, is the Republic, and above the Republic, the revolution.

In another order of things, Azaña, in these first months of 1934, dedicated almost exclusive attention to the issue of the necessary union between the left-wing republican parties, as the only way of arbitration between the polarization already begun between the Catholic right and the Socialist Party. In this context, Acción Republicana was dissolved to merge with the Autonomous Galician Republican Organization and the Independent Radical Socialist Party in the new formation called Republican Left, which would be born at the beginning of April under the presidency Azana himself. From his first speech in office, he made clear his disgust toward those Republicans who had chosen to ally with an anti-republican right to run the country and, implicitly, disowned any future alliance with the first.

Beyond this, Azaña entered a political semi-retirement and returned to literary and editorial activity. The books Una política and In power and in opposition, compilations of parliamentary speeches, date from these dates. However, an early government crisis, which ended with Lerroux as president, made Azaña return to the first political line, establishing talks with the center and right-wing republicans in order to bring Alcalá Zamora the proposal for a national republican defense government, in order to redirect the political situation by dissolving the Cortes. The President of the Republic did not agree and the matter did not go beyond the recomposition of personal relations between the different republican leaders of the left and center-right. Azaña tried again to achieve a coalition with the Socialists for electoral purposes, but it was impossible, given their animosity towards the republican system, which from the pages of El Socialista was considered a regime no better than the monarchy.

On August 30, during a short vacation in Catalonia motivated largely by reasons of personal security (in Madrid he was forced to change his address frequently to avoid attacks by violent right-wing elements), he was honored with a banquet at the which was attended by 1025 people, at the end of which he gave a speech in which he analyzed the political situation of the moment. Fundamentally, he expressed his complaint that politics had fallen into the hands of political gangs and stated that the situation had only two possible escape routes, linked to his new ascent to the presidency of the government: the suffrage or revolution. He explicitly avoided the electoral path, assuming a certain defeat against the center-right given the extreme division of the left; As for the revolution, he reminded once again that an overthrow of the republican regime from within could not be allowed. At the beginning of October, the Samper government broke up and Lerroux was commissioned to form a new government, which included three CEDA ministers. Almost immediately, the government of the Generalitat proclaimed the Spanish Federal Republic and the Catalan State within it, a project in which Azaña refused to get involved because he considered that his fidelity lay with the Constitution and the Statute; Also, at the beginning of October a general strike took place throughout Spain, in which the events that occurred in Asturias were especially serious. Simultaneously, rumors began to spread of a revolt (already in circulation since the end of September) and of the imminence of Azaña's ascension to the presidency of the Republic. As a consequence of all this, and of the circumstantial presence of Azaña in Barcelona where the start of that revolt was expected, on October 8 he was arrested by the military authority.

He was imprisoned on different navy ships (the ship Ciudad de Cádiz and the destroyers Alcalá Galiano and Sánchez Barcáiztegui), where he was interrogated several times by different judges in relation to the rebellion in Barcelona, with a cache of arms found on the steamer Turquesa on the beach of San Esteban de Pravia and with some contacts with Portuguese citizens, supposedly to help them prepare in Portugal in 1931 something similar to the proclamation of the Second Republic in Spain. In the Ciudad de Cádiz he was held in incommunicado prison, despite which his wife Dolores traveled to Barcelona by train under intense police surveillance and finally got a brief interview with her husband under the pretext of carrying out notarial management.

On December 28, the Supreme Court decided to dismiss the proceedings and released him. Azaña would recount these events in his book My Rebellion in Barcelona , where he, incidentally, openly criticizes certain sectors of Catalan nationalism which he calls anti-democratic, authoritarian and demagogic . During his imprisonment there was a wave of displays of affection towards him in identical proportion to the criticism he received from the monarchist and Catholic right. The result of this confrontation of appreciations about the character gave rise to a clear division between staunch supporters (azañistas ) and detractors of the same, which would last over time and which would symbolize in he the budding civil confrontation, as Azaña himself was already malicious at that time. At the beginning of January 1935 he resolved with several members of the National Council of the Republican Left to maintain the identity of the party and fidelity to the Constitution, and to insist on the need for unity between the republican parties with a view to the following elections. In those first months he also had to face an accusation, which would come to nothing, promoted by the CEDA and the radicals, which held him responsible for the sale of a shipment of arms to the revolutionary socialists of Asturias.

On March 20, he gave a speech in Congress in which he broke all possible political relations with Alcalá Zamora (whom he blamed, in part, for the political crisis for having given rise to rumors of all kinds) and appealed to the need for a dissolution of the Cortes and a call for elections to get out of the delicate political situation of the moment. At the end of May, with a massive rally at the Mestalla soccer field in Valencia (described by the newspaper El Sol as "the most important event in recent times"), he began a series of public acts in order to vindicate the validity of the Republic and the need for a coalition between the parties related to it. His personal success was enormous and the rally in Campo de Comillas, near Madrid, which also attracted a huge crowd (of around half a million attendees), was even advertised by the newspaper Pueblo , organ of the PCE; his political rival Gil-Robles affirmed that "no one, neither in Spain nor abroad, had ever achieved such an impressive audience". His speeches insisted on the usual ideas: politics based on the Constitution, and a Constitution, moreover, reformist in the social order and founded on universal suffrage. One of the first consequences of this activity was the reestablishment of his relations with Indalecio Prieto, to the point that he invited him on a trip with his wife to Belgium in September. Upon his return to Spain, however, Largo Caballero maintained his refusal to join any coalition with the Republicans, exemplifying the manifest break between his line and Prieto's. However, a government crisis that seemed to precipitate the accession of the CEDA leader to power led Largo Caballero to rectify in November, accepting the coalition proposed by Azaña, a coalition only for the elections (never for the government).) and in which trade unionists and communists should be included. People dubbed the new left-wing Republican coalition the Popular Front.

President of the Government again

On February 16, 1936, this coalition of left-wing parties was victorious by a narrow number of votes, although the victory was resounding in seats. Immediately, the president of the Council, Manuel Portela Valladares, resigned and Azaña took over the government without the Cortes having been constituted. Azana's messages to the population were constantly in the same direction:

Calm the moods, settle democracy, apply the electoral program loyally, democratize the army to avoid situations like those of the last hours [after the victory of the popular front, there were rumors of coup d'etat], approve the amnesty [for the reprisals of the October revolution], restore order, apply the law.

On February 19, 1936, the new government was formed, which presented a coalition of the Republican Left and the Republican Union. At the same time that he managed the aforementioned prisoner amnesty and reestablished relations with Catalonia by annulling the suspension of the Statute, the state of alarm that existed in the country allowed him to imprison the senior staff of the Spanish Falange for the attack committed by a Falangist on 12 March against the vice president of the Cortes, Luis Jiménez de Asúa (in which only his escort would die). To the tension and violence that was being experienced in the country, Azaña countered a speech in Parliament on April 3 in which he tried to calm things down, especially given the disorientation of the two parties with the largest parliamentary representation and the greatest popular following: the CEDA and the PSOE. On April 15, he presented his government before the Cortes, but already with the idea of acceding to the Presidency of the Republic, in the belief that his popularity qualified him more for that position as an arbitrator than in the presidency of the government. For the rest, from there it also had the objective of definitively incorporating the socialists into the government.

On April 30, he was elected the sole candidate for the Presidency of the Republic from all the parties that made up the Popular Front. After the dismissal of Alcalá-Zamora (whose liberal-democratic party had suffered a setback in the elections), he was elected President of the Republic on May 10, 1936 with 754 votes out of 847 deputies and delegates, promising the position up to date. following.

President of the Republic and Civil War

The new head of state moved his residence to the Quinta palace in El Pardo, a fact that could have cost him his life. At that time, a majority of the officers of the Pardo Transmissions regiment were involved in the uprising; among them Captain José Vegas Latapié, who had planned the kidnapping of Azaña. His brother, the conspirator and anti-republican propagandist Eugenio Vegas Latapié, was also involved (in fact both would join the coup leaders two months later), although in the end the project was aborted.

With the background of an ongoing military conspiracy and a worker and peasant mobilization, Azaña entrusted the presidency of the government to Santiago Casares Quiroga, who formed an exclusively republican one, and entered the institutional dynamics of his new position, without doing much case of everything that was brewing. Thus, when the coup took place, the government collapsed almost immediately. Casares Quiroga resigned on the afternoon of July 18 and Azaña, from the National Palace (now the Royal Palace, where he had been transferred for security), promptly commissioned the President of Parliament, Diego Martínez Barrio, to form a government that would incorporate elements of the right and not incorporate communists. However, the PSOE, through the mouth of Indalecio Prieto (but following Largo Caballero's strategy), refused to participate in such a government. However, on the morning of the 19th, he had formed a government with members of the Republican Left, the Republican Union and the National Republican Party (without socialists or communists, therefore).

Martínez Barrio came to speak with some of the rebel generals (Cabanellas and Mola), but there was no going back. In addition, both socialists and anarcho-syndicalists and communists also rejected any kind of turning back and demanded arms to face the uprising, refusing to recognize the new government. Martínez Barrio resigned the same day 19. Azaña then brought together the parties in order to find a satisfactory solution for all. Largo Caballero made socialist participation conditional on the distribution of arms to the unions and the licensing of all soldiers. Azaña then entrusted the formation of the government to José Giral, who formed an exclusively republican one and who assumed the distribution of arms. On July 23, Azaña gave a radio address to the country in which he encouraged and thanked those who defended the Republic for their efforts, vindicating his legitimacy and condemning his aggressors. However, simultaneously with these externalizations,

those who had visited him a few weeks earlier and returned now for talks with him again proved a rapid aging, a marked paleness on his face, an obvious tiredness, a tremor of emotion in the voice when he evoked the atrocities of the insurgents and the sacrifice of the people, although he spoke without resentment and without showing any vengeance.

In early August, learning that France and the United Kingdom were not going to support the Republic with arms, Azaña became convinced that there would be no way to win the war. On August 22, the Modelo prison in Madrid was stormed by a crowd and several of Azaña's personal friends were assassinated, including Melquíades Álvarez. As a result of everything, the next day Azaña considered resigning, although Ángel Ossorio y Gallardo finally helped him to reconsider his intention. For the rest, a new problem became visible in Spain: indiscipline, the fragmentation of power and the desire for revenge.

The widespread disorder caused José Giral to resign at the beginning of September and with him the entire government. Giral recommended a government that, due to its influence on the people, would include unionism; Azaña, despite considering the unions as the main responsible for the chaos, ended up accepting the leader of the UGT, Largo Caballero, as president of the government. The new coalition government was made up of socialists, republicans, communists and a member of the PNV. Given the proximity of Franco's army to Madrid, the government decided that Azaña would move from Valencia to Barcelona. Before leaving, he gave an important speech at the Valencia City Hall on January 21, 1937, in which he said: "We make war because they make it to us." Six months later, on July 17 (the first anniversary of the start of the war), he delivered another significant speech at the University of Valencia:

We have to become accustomed again to the idea, that it can be tremendous, but that it is inexcusable, that the twenty-four million Spaniards, as much as they kill each other, will always remain quite a lot, and what remains need and obligation to continue living together so that the nation does not perish.

At the end of October, he established his residence and office in the Palacio de la Ciudadela. From there, in the same month of October and anticipating a difficult republican triumph, he tried, through the ambassadors in England and Belgium, to mediate with the British to achieve an end to the war so that the Spanish could decide their future. peaceably. However, the favorable environment for the uprising in both countries put an end to the attempt. On November 2, Azaña changed his residence to the Monastery of Montserrat. There he received the news that Largo Caballero had granted four ministries to the CNT, partly thanks to a misunderstanding between Azaña and Giral, who had mediated in the matter. Azaña was upset (as opposed as he was to entrusting political posts to unions), and exposed to the president his special opposition to the presence of FAI ministers, but there was no turning back.

Throughout the following months, Azaña had to resist different attacks of his state of mind before the events that were unfolding, but he resisted without abandoning his position for various reasons:

the first was his clear and forceful repudiation of the rebellion, which he defined from the beginning as an aggression without example, as horrendous guilt, a "crime not of the country, but of the humanity", putting in the face of its perpetrators the crime of tearing the heart of the homeland. He never found any justification or explanation for this crime: "although all the evils that were charged to the Republic were true, there was no need for war. It was useless to remedy those evils. They were all aggravated, adding to them those who are so devastated." The second (...) was their respect for the fighters. (...) the third (...) is the very cause of the Republic (...) the Republic was the law, order, coexistence, democracy and those values had given its life.

Azaña lived for several months in reclusion and sadness between Montserrat and Barcelona, and outside the Republican government. Finally, in December 1936, Ángel Ossorio encouraged him to go to Valencia, to which Azaña agreed.

In January 1937, he gave a speech at the Valencia City Council in which he stressed that, although the war was, originally, an internal problem due to the rebellion of a large part of the army against the State, due to the presence of forces from different countries had become a serious international problem. And that Spain was fighting, therefore, also for its national independence. In this sense, he insisted on his efforts so that the signing of a cessation of hostilities would facilitate the departure of foreign powers from Spain and, incidentally, a reestablishment of relations between the parties in conflict to, finally, reach a referendum that would clarify the future.

Back in Catalonia, he moved to live in Barcelona, although he made frequent visits to Valencia, where the government was based. He thought of a plan, which he communicated to several members of the government (which he shared in March 1937), which consisted of the blockade of arms and contingents, and the re-embarkation of foreign fighters with a suspension of arms, for which the intervention of the United Kingdom and France would be necessary; he did not receive the necessary attention from the government and ultimately came to nothing.

At the beginning of February 1937, he also had in mind that the only way to redress the situation of failure in the war was to get the unions out of the government and leave it in a coalition of communists, socialists and republicans. Stalin himself complained that the war was not taken seriously and that there was no military discipline. The anarchist insurrection in Barcelona in May intensified the separation between Azaña and the government of Largo Caballero, which remained quite passive regarding the revolt, to the point that Azaña once again considered resigning. Azaña, however, continued, and later managed a new government crisis with a view to getting Largo Caballero to leave the presidency of the government, which he would achieve thanks to the joint pressure of socialists and communists, and the acquiescence of republicans.

Although it was expected that the replacement would be Indalecio Prieto, Azaña opted for Juan Negrín because he did not trust the former's ups and downs and because he seemed more apt to lead a coalition government, given his correct relations with all the political forces. All in all, the decisive reason was to understand that Negrín was the most appropriate politician to attempt, once again, a way out of the war through international mediation, which at the time of the change of president, in May 1937, had better prospects. than on previous occasions. However,

the proposal of a plan of intervention of the foreign powers that left the war on boards (...) did not come into the horizon of the insurgent commands or their ecclesiastical allies that, by then, had already redescribed the "alzation" as a "cross" that could only end the liquidation and extermination of the adversary.

Around that time, Azaña settled in La Pobleta, a farm near Valencia, where he began what he would later call the Cuaderno de La Pobleta. Political and war memories , where he recorded a multitude of conversations with different personalities of the moment.

He pointed out to the new government what he considered to be the priorities of the moment: the defense of the interior (with special mention of Catalonia, where it was necessary to restore the authority of the government) and not losing the war abroad. Regarding the latter, in a new speech delivered on July 18, he once again openly criticized the passivity of the United Kingdom and France in relation to the war in Spain. In November 1937 he went to Madrid and gave a new speech at the town hall, now very focused on the moral aspects of the war and its reality and calamitous consequences for everyone, something he was moved to see when he visited Alcalá the next day.

In December he moved again to Catalonia, now near Tarrasa, at the La Barata farm, together, as always, with his wife and his closest collaborators. He insisted on the armistice, but now both the Central Committee of the Communist Party and Franco have expressed their rejection of it; for the rest, the Negrín government did not seem to accept that possibility either. After the offensive on Teruel and the collapse of the Aragon front, Franco arrived in the Mediterranean in April 1938. Azaña reaffirmed his idea of the impossibility of winning the war and that, therefore, any effort in the direction of achieving victory military was doomed to fail. Thus, then, the frustrated offensive of the Republic in the military field, which obviated the defensive idea that Azaña advocated to force foreign intervention, ended up losing all hope that it would come to pass.

At the end of February 1938, he had clearly stated to the French ambassador the need to end the war immediately. In this sense, he proposed that France and the United Kingdom take over the naval bases of Cartagena and Mahón to balance those that Franco's army had in Ceuta, Málaga and Palma; the counterpart would be the search for peace in Spain. The communication cut between Barcelona and Valencia put the government in a bind, and Negrín had to ask for help directly from France on March 8. The situation worsened in Spain and he had to return in a week with a mediation proposal from the French government. The Negrín government failed to agree on it, partly because Negrín himself, for example, was convinced of victory, and it was rejected on March 26. Azaña thought of replacing Negrín as head of the government, taking refuge in the criticism he received for his relationship with the communists, which had partly caused Prieto's departure from the government, and the situation of the war in general. At the beginning of April, Azaña summoned the government with the hope of being able to get out of it with Negrín dismissed, but it was not possible. His position was, in short, weakened, to the point that Prieto had to convince him not to resign.

because your resignation would demolish everything; for you personify the Republic that respect the non-allied countries of Franco.

However, his disappointment was so great that in the middle of that same month he sent a money transfer worth one million French francs to Cipriano de Rivas (which he would convert into gold dollars) to prepare for his family's exile in France.. On May 1st, a thirteen-point declaration signed by the Government of the National Union was presented, which highlighted the objectives, among others, of defending the independence of Spain from all foreign powers and establishing a Democratic Republic, and announced a great amnesty for those who wanted to collaborate in it.

On July 18, 1938, in the Barcelona City Hall building, he delivered a famous speech in which he urged reconciliation between the two sides, under the motto Peace, mercy and forgiveness. The core of the speech was the expression of his idea of what was being the most serious damage that the war was causing in Spain:

a dogma that excludes from nationality all who do not profess it, be a religious, political or economic dogma, [the one who opposes] the true basis of nationality and patriotic feeling: that we are all children of the same sun and tributaries of the same stream.

At the end of that month, he had a conversation with John Leche, a British charge d'affaires, in which he offered Negrín's head and the removal of the communists from the government in exchange for British intervention imposing a suspension of arms. The British response was what it had been up to now: his policy was non-intervention. The defeat in the battle of the Ebro precipitated the events by making the government enter into a continuous crisis. On January 13, 1939, Azaña received a notice from General Hernández Saravia asking him to leave Spain. On the 21st he left Tarrasa along with his family and various collaborators, and went first to Llavaneras and then to the castle of Peralada, where he arrived on the 24th. There they learned that Barcelona had been taken by Franco's army. On the 28th he received a visit from Negrín and General Rojo, the chief of the General Staff, who presented a report that proposed a surrender plan and a transfer of powers between the military. Azaña asked Negrín, who seemed to agree, to bring the government together to make a decision. However, two days later the president of the government returned, but noting to Azaña that his idea was to continue resisting until the end.

Once the French government opened the way for civilians and soldiers across the border, between January 28 and February 5, Azaña, his family and his collaborators headed towards it. They deviated from the main road towards La Bajol and there he met Jules Henry on February 4 to tell him that he did not agree with Negrín's decision to continue the resistance; insisted, once again, on the need for France and England, with the support of the United States, to intervene in the end, presenting a peace plan to Franco that, basically, would facilitate humanitarian treatment for the defeated, including political leaders and military of the Republic. Negrín did not accept because, regardless of his insistence on continuing the war, he understood that Franco would never accept that type of peace.

That same day, the 4th, Negrín personally informed him that it was the government's decision that Azaña take refuge in the Spanish embassy in Paris until he could organize his return to Madrid. Azaña made it clear that, after the war, there was no possible return to Spain.

On February 5, they resumed their journey toward exile. In total, there were about twenty people, the older ones going in police cars. Before reaching the top of a pass, one of the cars broke down and, preventing the others from passing, forced them to continue the journey on foot, arriving at dawn. They crossed the border through the customs post; They were, among others, Azaña, his wife, Negrín, José Giral, Cipriano de Rivas and Santos Martínez. They descended towards Les Illes through an icy ravine.

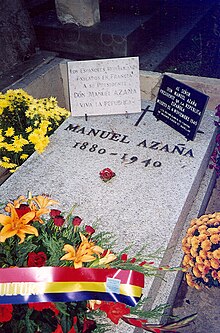

Resignation and death in exile

From Les Illes they traveled to Collonges-sous-Salève, where they arrived on February 6 to settle in La Prasle, a house that his brother-in-law, Cipriano de Rivas Cherif, and his wife, Carmen Ibáñez Gallardo, had rented the summer of 38. From there, he confirmed to the ambassador in France, Marcelino Pascua, that he would arrive in Paris on the 8th, where he would stay for several days.

On the 12th General Rojo offered him his resignation and on the 18th Negrín sent him a telegram urging him that, as president, he should return to Spain. Azaña, however, was clear that he was not going to return, just as he was clear that he would present his resignation as soon as France and the United Kingdom recognized Franco's autarkic government. Thus, he returned to Collonges on February 27 (two days after the go-ahead for the establishment of diplomatic relations with Spain was given) and from there he sent the letter of resignation to the president of the Cortes.

The recognition of a legal government in Burgos by the powers, uniquely France and England, deprives me of the international legal representation to make the foreign governments heard, with the official authority of my office, which is not only dictated my Spanish conscience, but the deep longing of the vast majority of our people. Disappeared the political section of the State, Parliament, superior representations of the parties, etc., I lack, within and outside Spain, the organs of Council and of action indispensable to the presidential function of channeling the activity of government in the manner that circumstances require with empire. In such conditions, it is impossible for me to keep or nominally continue my post to which I did not resign on the same day that I left Spain because I hoped to see this time span taken advantage of for peace.

On March 31, at a meeting of the Permanent Deputation of the Congress of Deputies in Paris, Negrín harshly criticized Azaña's decision not to return to Spain, calling him almost a traitor, words that, at least, were supported by Dolores Ibarruri.

Azaña's comment on those statements, made known through a letter to Luis Fernández Clérigo, occurred on July 3 and went in the direction of insisting on what has already been stated on other occasions: the intrinsic illegitimacy of the new regime against to republican legitimacy, which was based not on the survival of the institutions in exile but on having been elected by the Spanish people, something to which they would eventually have to return. For the rest, he decided to withdraw from any personal political activity convinced that it would be completely useless. In his opinion, what had to be tried was not so much the Republic, but rather the national emotion that it represented, while the most important thing was to recover the conditions so that the Spaniards could choose freely the regimen they wanted.

Isolated, therefore, from politics, he tried to focus on his intellectual work and decided to publish a retouched version of the 1937 diaries under the title Political and War Memories. The notebooks of La Pobleta and his work in dialogue with him The evening in Benicarló . Only this second one was published in August 1939 in Buenos Aires. He also began a series of articles on the war in the magazine The World Review , but it would not continue because the outbreak of World War II shifted journalistic interest towards it. In his first article, Azaña insisted on two of his most frequent ideas in relation to the war: to hold Franco-British politics responsible for the disaster of the Republic, also responsible, by omission, for the meddling of the Soviet Union in Spain; and in the need to resist not to win, as Negrín wanted, but to force the enemy to finish negotiating.

Between April and December 1939, pressure from the new Spanish ambassador to France, José Félix de Lequerica, ended up having its effects, but more in Spain than in France. There it was decided to apply the law of February 9 of political responsibilities (LRP) to Azaña, for which the investigating judge had to collect various reports from various parties. It is in these reports that the vision of Manuel Azaña that the new regime wanted to popularize is clearly exposed for the first time: enemy of the army, religion and the homeland, sexual pervert, Freemason and Marxist. The consequence of the order was the seizure of all his assets (seized by the Spanish Falange, previously) and a fine of one hundred million pesetas. On April 28, 1941, the provincial court of the LRP will propose to the Council of Ministers that the former president of the extinct Republic (now deceased) be even stripped of Spanish nationality (by virtue of article 10 of said law).

Azaña remained in Collonges until November 2, when fearing that France would be invaded by Germany, he had to move to Pyla-sur-Mer, near Bordeaux, settling in the villa L'Éden with his wife and brothers-in-law, among others.

In early January 1940, he developed flu-like symptoms that he had already manifested the previous summer. The doctors, however, discovered a very serious aortic condition with considerable dilatation of the heart and various problems in the cardiac system. Until May, his health was very delicate: