Mammalia

The mammals (Mammalia) are a class of homeothermic (warm-blooded) amniotic vertebrate animals that have milk-producing mammary glands with which they feed their young. Most are viviparous (with the exception of monotremes: platypus and echidnas). It is a monophyletic taxon; that is, they all descend from a common ancestor that probably dates back to the late Triassic, more than 200 million years ago. They belong to the synapsid clade, which includes the so-called mammalian reptiles, a group of synapsids that were neither reptiles nor mammals, although they were more related to the latter than to the former, such as pelycosaurs and cynodonts. Some 5,486 extant species are known, of which 5 are monotremates, 272 are marsupials, and the rest, 5,209, are placentals.

The specialty of zoology that specifically studies mammals is called theriology, mammalogy, or mammalology.

Features

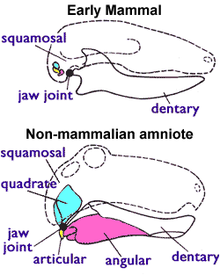

Down: pelicosaurus skull (“reptil” mamiferoid), in which it is observed as the lower jaw is articulated with the square and consists of several bones (dentary, angular, joint).

The class of mammals is a monophyletic group, since all its members share a series of exclusive evolutionary novelties (synapomorphies) that do not appear in any other animal species not included in it:

- They possess sweat glands, modified as breast glands, able to segregate milk, food from which all mammals are supplied. This is their main characteristic, from which they derive their name from mammals.

- The jaw is formed only by the dentary bone, unique and exclusive trait of all mammals, constituting the main diagnostic characteristic for the group.

- They present seven vertebrae in the cervical segment of their spine; biological constant that is verified in species as dissimilar as the mouse, giraffe, ornitorrinco or blue whale.

- The joint of the jaw with the skull is made between the dentario and the scamosal, also unique and exclusive feature of the mammals.

- They present three bones in the middle ear: hammer, yunque and estribo, with the exception of the monotremas, which present the reptilian ear.

- The mammals have atrial pavilions, except whales, dolphins and others living in the water and that in their evolutionary process have lost them for hydrodynamic reasons.

- They are the only current animals with hair present in almost all stages of their life, and all species, to a greater or lesser extent, have it (although it is in embryonic state).

- Like their primitive ancestors, modern mammals possess a single pair of temporary fenstras in the skull, unlike the diagnoses (dianosaurs, modern reptiles and birds), which present two pairs, and the anathos (tortugas), which have none. In addition to this skeletal difference—and other less significant ones such as the importance of the dental bone in the lower jaw and the heterodontic condition or ability of the teeth to perform different functions—the main characteristics of the mammals are the presence of hair and skin glands.

But despite these and other similarities that are not defining the class, its diversity is such that there are many more differences, especially in terms of external appearance.

Anatomy and Physiology

The synapomorphic characters of the class Mammalia have already been noted. All the species present them and they are exclusive in addition to the class:

- The dentario as the only bone in the jaw, which is articulated with the squamous in the skull.

- Middle ear bone chain: hammermalleus), yunque (incus) and stribo (stapes).

- Hair on the surface of your body.

- Milk production in the breast glands.

- Presence of seven vertebrae in the cervical segment of the spine.

Teeth are made up of substances that do not belong to the skeletal system, but to the integumentary system, such as skin, nails, and hair. The matter that forms the body of the tooth is ivory or dentin, which is generally covered on the outside with another very hard substance, enamel, while at the base of the tooth the external envelope is made up of a third substance called cementum..

In mammals, the teeth are always inserted in the skull bones that surround the mouth, which are, above, two maxillae and two premaxillae, and below, a mandible or jawbone, which articulates directly with the jawbone. skull. The latter, in turn, connects with the vertebral column through two bulges, or condyles, which are on either side of the hole through which the spinal cord enters to join the brain. Although the number of vertebrae in the spinal column varies greatly depending on the species, there are seven cervical or neck vertebrae in all mammals except sloths, which can have up to 10, and manatees, which only have six. But, in addition, there are other characteristics common to these species that also serve to identify them as part of the taxon:

- The mammals are the only animals that have one bone in each jaw, the dentario, articulated directly with the skull. The bones of the jaw of the reptiles were transformed into two of the three bones that form the bone chain of the ear, the hammer (articular) and the yunque (square). The stribo comes from the only bone that presents reptiles in the ear, the columella.

- The teeth are highly specialized according to the eating habits, and are generally replaced once in life (diphyodontia).

- There is a secondary palate that is able to separate the passage from the air into the trachea of the transit of water and food to the digestive system.

- Diaphragm is a muscle structure that separates chest cavity from the abdominal and contributes to digestive and respiratory functions. It is only found in mammals and all species possess it.

- The heart is separated into four cavities and only the left aortic arch develops in adults.

- Hematites are non-nucleus cells in most mammal species.

- The cerebral lobes are well differentiated and the cerebral cortex very developed, with marked circumvolutionions more evident in species with greater intellectual capacity.

- Sex is determined from the very moment of the formation of the zygote by the sexual chromosomes: two different in the males (XY), two equal in the females (XX).

- Fertilization is internal in all species.

- All species are endothermal, that is, they can produce heat with their body, and most are also homeothermal, or what is the same, they can keep the temperature within a given range. Only monotremas present certain limitations of this capacity.

Skin

The skin, generally thick, is made up of an outer layer or epidermis, a deep layer or dermis, and a subcutaneous layer full of fat that serves as protection against heat loss, since mammals are homeothermic animals.

It contains two of the synapomorphies of the Mammalia class: hair and mammary glands.

It is directly involved in animal protection, thermoregulation capacity, excretion of waste products, animal communication and milk production (mammary glands).

Other skin formations of a horny nature that mammals have are nails, claws, hooves, hooves, horns and the beak in the case of the platypus.

Locomotor system

The locomotor system is the set of systems and tissues that make it possible to maintain the animal's body and its movement.

- Skeleton:

- Axial skeleton:

- Head: skull and jaw.

- Spinal column: cervical vertebrae, thoracics, lumbars, sacrals, or coxygee.

- chest box: stern and ribs.

- Appendicular skeleton:

- Capular waist: collarbone and omoplates or scapulars.

- Previous tips: humerus, cubit, radio, carpos, metacarpos and phalanges.

- Pelvic tape: ilion, ischion and pubis.

- Subsequent extremities: femur, kneel, tibia, perone, tarsos, metatarsos and phalanges.

- Axial skeleton:

In addition, there are other bone formations such as the bones of the hyoid apparatus (support of the tongue), of the middle ear, the penile bone of some carnivores and even the cardiac bones of some bovids in which the cardiac cartilage ossifies.

In addition to the skeletal system, the locomotor system is made up of the muscular system and the joint system.

Digestive system

The digestive system consists of an inlet, or esophagus, an intestinal tube with an outlet to the outside, and a stomach, plus some adjoining glands, the most important of which are the liver and pancreas. With few exceptions, the food undergoes prior preparation, chewing, through the teeth, hard organs that line the mouth and whose number and shape vary greatly depending on the diet of each animal. In most cases there are, first of all, some cutting teeth, called incisors, then others suitable for tearing, which are the fangs, or canines, and, finally, others that are used to crush and grind, called molars or molars. As a general rule, mammals have one set of teeth when they are young and later change them to others.

The digestive system of mammals is a tubular visceral complex in which food is subjected to intense treatment to obtain the maximum use of nutrients.

During the digestive transit, from the moment it is ingested until it is excreted, the food is subjected to an intense process of mechanical and chemical degradation in which a series of strategically linked organs and tissues intervene.

- Scheme of digestive transit:

- Mouth: chewing and insalivation with absorption of scarce components.

- Esophagus: transit with low absorption.

- Stomago: mechanical and chemical digestion with partial nutrient absorption.

- Thin Intestine: mechanical and chemical digestion (enzymatic and bacterial) with abundant nutrient absorption.

- Thick Intestine: mechanical and chemical digestion (bacterial) with water absorption and mineral salts, mainly.

- Anus: elimination.

The animal's diet significantly determines the physiology and anatomy of this organic apparatus.

Respiratory and circulatory systems

These two devices are responsible for the exchange of gases and their distribution throughout the body.

Mammals breathe the oxygen present in the air that is inspired through the respiratory tract (mouth, nose, larynx and trachea) and is distributed through bronchi and bronchioles to the entire saccular complex that constitutes the pulmonary alveoli.

Blood coming from the tissues carries carbon dioxide and when it reaches the alveolar capillaries, it eliminates it while it captures oxygen. this will be transported back to the heart and from there to all the tissues to provide them with the necessary gas for cellular respiration, transporting the residual carbon dioxide back to the lungs.

The design and functioning of all these organs and tissues is perfectly synchronized to make the process profitable, especially in aquatic or subterranean species in which the oxygen supply is limited.

Nervous system and sense organs

The nervous system is a complex set of highly specialized cells, tissues and organs whose mission is to receive stimuli of a different nature, transform them into electro-chemicals to transport them to the brain, translate them here and order a response that will be transmitted again as electrochemical signals to the organ or tissue involved in its execution.

The scheme of the nervous system is basically:

- Central nervous system:

- Encephalo: Brain, brain and brain stem.

- Spinal cord.

- Peripheral nervous system:

- Nerves.

- Neuronal Ganglios.

The sense organs, for their part, are organs rich in nerve endings capable of translating external stimuli into information to relate the individual to their environment. In general, the most important in mammals are smell, hearing, sight and touch, although in certain groups, other senses such as echolocation, magnetosensitivity or taste become more important.

Poison

Mammals have not specialized in the development of toxins in the same way as other classes such as amphibians or reptiles. Due to its large size, physical strength and the use of claws and fangs have been enough to feed and defend itself. However, some small mammals of the orders Monotremata, Chiroptera, Primates and Eulipotyphla have opted for the use of toxins as an evolutionary strategy. For example, the Solenodon paradoxus has developed a hypotensive venom that it uses when hunting prey.

The vast majority of venomous mammals belong to the order Eulipotyphla. An evolutionary convergence can be observed in the composition of the venom and it is produced in the submandibular salivary glands from KLK1.

Playback

In all mammals the sexes are separated and reproduction is viviparous, except in the group of monotremes, which is oviparous.

The development of the embryo is accompanied by the formation of a series of embryonic annexes, such as the chorion, amnion, allantois and the yolk sac. The villi of the chorion, together with the allantois, attach to the wall of the uterus and give rise to the placenta. This remains attached to the embryo by the umbilical cord, and it is through it that substances from the mother's body pass to that of the fetus.

The gestation period and the number of pups per litter vary greatly between groups. Normally, the larger the animal, the longer the gestation period and the fewer the number of offspring. Most mammals provide their children with parental care.

Lastly, the way they reproduce is also characteristic of mammals. Although some species are oviparous, that is, the fertilized ovum leaves the outside forming an egg, in the vast majority the embryo develops inside the mother's body and is born in a more or less advanced state. From here is derived a first classification of the group into mammals that lay eggs and viviparous mammals. The latter have been called therios, a term derived from classical Greek meaning "animals", and those that are oviparous, prototerios, that is, "first animals", since the fossil record allows us to assume that the first mammals that appeared in the world belonged to this category.

In the therians, it is still possible to distinguish between mammals whose children are born in a very delayed state of development, having to spend some time in a bag that the female has on the skin of the belly, and those others in which no similar is observed particularity. The first are the metatherians (also called marsupials), that is, "the animals that come behind", those that follow the prototherians, and the last ones are the eutherians or placental mammals. Within the class that concerns us, these constitute the vast majority.

Diversity

Mammals constitute a very diverse group of living beings and, despite the small number of species that make it up in comparison with other taxa of the animal or plant kingdom, their study is by far the deepest in the field of Zoology.

To illustrate with an example this phenotypic, anatomo-physiological and ethological diversity, it is enough to list some of its species, such as the human being (Homo sapiens), a red kangaroo (Macropus rufus), a chinchilla (Chinchilla lanigera), a white whale (Delphinapterus leucas), a giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis), a lemur ring-tailed cat (Lemur catta), a jaguar (Panthera onca) or bats ("Chiroptera").

Just by comparing the largest animal species that has ever existed, the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus), which can reach 160 t, with the Kitti's hog-nosed bat (Craseonycteris thonglongyai), considered the smallest mammal, whose adults barely weigh 2 g, we can see that the difference in body mass between the more and less voluminous species is 80 million times.

The great adaptability of the individuals that make up the class has led them to inhabit all the ecosystems of the planet, which has given rise to a multitude of anatomical, physiological and behavioral differences, making them as a whole one of the dominant groups on Earth. They have been able to colonize the green canopy of the jungle and the subsoil of the deserts, the cold polar ice and the warm tropical waters, the rarefied environments of the high peaks and the fertile and extensive savannahs and grasslands.

They crawl, jump, run, swim, and fly. Many of them are capable of taking advantage of the widest range of food resources, while others are specialized in certain foods. This myriad of circumstances has forced these animals to evolve adopting a multitude of forms, structures, capacities and functions.

It is curious to see how in many cases, species very distant from each other geographically and phylogenetically have adopted similar morphological structures, physiological functions and behavioral aptitudes. This phenomenon is known as convergent evolution. The similarity in the head of a gray wolf (Canis lupus, a placental), and a thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus, a marsupial), is surprising, being two species so far apart phylogenetically.

The common European hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus, placental) and the common echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus, monotreme) can confuse any layman, since they have not only adopted the same defense structure, but rather share similar morphologies to exploit similar food resources.

Adaptation to very diverse environments

The great diversity of mammals is the result of an extraordinary capacity for adaptation that has allowed them to be distributed throughout the vast majority of the planet's environments.

The mechanisms developed by each species to adapt to the environment evolved independently. Thus, while some species such as the polar bear (Ursus maritimus) protected themselves from the cold with a dense layer of fur that appears white with light reflection, others such as pinnipeds or cetaceans did so. producing a dense layer of fatty tissue under the skin.

In other cases, phylogenetically very distant species resort to similar mechanisms to adapt to similar circumstances. The development of the auricles of the fennec (Vulpes zerda) and the African elephant (Loxodonta africana) to increase the heat exchange surface and promote homeostasis is a clear example.

The reconquest of the waters by animals that were completely terrestrial is another example of the adaptability of mammals. Different groups of the class have evolved completely independently to return to the aqueous medium and exploit marine and fluvial niches.

To cite a few examples that illustrate the variability of the mechanisms developed to adapt to aquatic life, two orders whose species are strictly aquatic, Cetacea and Sirenia, the families of carnivores Odobenidae (walrus), Phocidae (seals) and Otariidae (bears and sea lions), mustelids such as the sea otter (Enhydra lutris) and other river species, rodents such as the beaver (Castor sp.) or the capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), Pyrenean desman (Galemys pyrenaicus), hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius), yapok (Chironectes minimus), the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus)...

Along with birds and the extinct pterosaurs, a group of mammals, bats have been able to move by active flight. Not only have they developed essential anatomical structures such as wings, but they have also developed physiological adaptations that allow energy savings, thus compensating for the tremendous cost of flight.

In addition, these animals, having to function in the strictest darkness of the night and inside the caves, have evolved perfecting the echolocation system that allows them to accurately perceive the world around them.

Moles and other sappers, mainly rodents, lagomorphs, and some marsupials, live underground, some spending most of their lives buried. They have managed to conquer the interior of the terrestrial surface, but the perception of the exterior, the movement underground, the relationships between individuals and the nutritional and respiratory requirements have been some of the issues that they have had to resolve throughout their evolution, suffering during it notable transformations and essential specializations.

Such specialization causes that, in case of an alteration of the environment, the species can reach extinction. In this way, species, families and even entire orders have disappeared as their habitat has been modified. In recent years, humans have caused the destruction of some natural environments. For example, the disappearance of virgin hunting grounds is causing the extinction of the Iberian lynx (Lynx pardina) and the clearing of forests has greatly threatened the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). In the same way, the introduction of foreign species such as cats, dogs or foxes has produced a reduction in the number of Australian marsupial cats.

Ecological paper

Trying to summarize the ecological role played by the approximately 5,000 species of mammals is as difficult as doing it with respect to all living beings and their environment, since given the diversity of colonized ecosystems, biological and social behaviors, as well as anatomy and morphological adaptations of all of them, gives rise to a variability unknown in any other animal or plant group on the planet, despite being the least numerous group in terms of diversity.

On the other hand, the high energy requirements due to the need to keep their body temperature constant significantly condition the repercussions that the interactions of these animals have on the environment.

In general, predators have a great impact on the populations of their prey, which in large numbers are other mammalian species, while precisely these can suppose in some cases the basis of food for many others.

There are species that, with few individuals, give rise to ecological interactions of great magnitude, as occurs with beavers and the water currents that they stop, while others, which supposes intense pressure is the number of specimens that come together as This is the case of the large herds of herbivores of the prairies or savannahs.

A separate chapter involves the interaction exerted by humans on each and every one of the ecosystems, inhabited or not.

Geographic distribution

Mammals are the only animals capable of being distributed over practically the entire surface of the planet, with the exception of the frozen lands of Antarctica, although some species of seal inhabit its coasts. At the opposite extreme, the range of the hispid seal (Pusa hispida) extends to the vicinity of the North Pole.

Another exception is the remote islands, far from the continental coasts, where there are only cases of species introduced by man, with the well-known ecological disaster that this entails.

On land, they are found from sea level to 6,500 meters above sea level, inhabiting all existing biomes. And they do it not only on the surface, but also under it, and even above it, both between the branches of the trees and having undergone anatomical modifications that allow them to fly actively, as in the case of bats, or passively, as in the case of bats. of colugos, gliders and flying squirrels.

The aquatic environment has also been conquered by these animals. There is evidence that throughout the planet, mammals populate its rivers, lakes, wetlands, coastal areas, seas and oceans reaching depths greater than 1000 meters. In fact, cetaceans and marine carnivores are two of the most widely distributed groups of mammals on the planet.

As taxonomic groups, rodents and bats, in addition to being the most numerous in terms of species, are the ones that have come to inhabit the largest areas, since except for Antarctica, they can be found all over the planet, including islands not so close to the coast, impossible to colonize by other terrestrial species.

At the opposite extreme, the orders with few species are those with the smallest global distribution area, with special mention to two of the three orders of American marsupials that are limited to a relatively limited area of the southern subcontinent, especially the little monkey del monte (Dromiciops australis), the only representative of the order Microbiotheria.

Sirenians, although with limited ranges for each of the few species with living specimens, can be found in Asia, Africa, Central and South America, and Oceania. Some orders are exclusive to certain continents, having evolved in isolation from the rest of the mammals, such as the cingulates in South America, the tubulidentates in Africa or the dasyuroformes in Oceania, to name a few examples.

If we except man (Homo sapiens), and the animals associated with him, both domestic and wild, from among the other species, perhaps they are the gray wolf (Canis lupus) or the red fox (Vulpes vulpes), the most widely distributed, since its specimens are found throughout most of the northern hemisphere. Also the leopard (Panthera pardus), which does so from Africa to India, or the puma (Puma concolor), from Canada to southern Patagonia, are two species with areas of very extensive distribution. Other carnivores such as the lion (Panthera leo), the tiger (Panthera tigris) or the brown bear (Ursus arctos) have spread widely part of the earth until relatively recent times, although their areas of distribution have been gradually decreasing until breaking up and ending up disappearing from most of them today.

In contrast, a much larger number of them occupy limited areas and not all because they have been reduced for some reason, but because throughout their evolution they have not been able or have not needed to extend them beyond the current ones.

But not only certain species have been the ones that have disappeared from more or less extensive regions of the planet, but also some entire groups of mammals that in other times inhabited certain continents, have not managed to survive until present times. Equidae, for example, which inhabited almost the entire planet in the wild, today only exist in freedom in Asia and Africa, having been reintroduced by man in a domestic state in the rest of the planet.

And in other cases the fortuitous or voluntary introduction of certain species in regions where they did not exist, has endangered and even caused the disappearance of native species.

Number of species by country

This section does not list all the mammal species of each country.

- Africa: Democratic Republic of the Congo (430 species), Kenya (376 species), Cameroon (335 species), Tanzania (359 species).

- North America: Mexico (523 species), United States (440 species), Canada (193 species).

- Central America: Guatemala (250 species), Panama (218 species), Costa Rica (232 species), Nicaragua (218 species), Belize (125 species), El Salvador (135 species), Honduras (173 species).

- South America: Brazil (648 species), Peru (508 species), Colombia (442 species), Venezuela (390 species), Argentina (374 species), Ecuador (372 species), Bolivia (363 species).

- Asia: Indonesia (670 species), China (551 species), India (412 species), Malaysia (336 species), Thailand (311 species), Burma (294 species), Vietnam (287 species).

- Europe: Russia (300 species), Turkey (116 species), Ukraine (108 species).

- Oceania: Australia (349 species), Papua New Guinea (222 species).

Social behavior

The high energy needs of these animals also condition their behaviour, which, although it varies substantially from one species to another, always has the goal of saving energy to maintain body temperature.

While mammals that inhabit cold regions of the planet have to avoid losing body heat, those that inhabit hot, dry climates direct their efforts to avoid overheating and dehydration. Therefore, everyone's behavior is aimed at maintaining physiological balance, despite environmental conditions.

Mammals, in general, exhibit all kinds of life forms: there are species with arboreal and other terrestrial habits, there are exclusively aquatic mammals and other amphibians, and even those that spend their lives underground digging galleries in the sand. Therefore, locomotion styles are also diverse: some swim, others fly, run, jump, climb, crawl or glide.

Social behavior is also very different between species: some are solitary, others live in pairs, in small family groups, in medium-sized colonies, and even in large herds of thousands of individuals.

On the other hand, they show their activity at different times of the day: diurnal, nocturnal, crepuscular, evening, and even those like the yapok (Chironectes minimus) that seem to show no circadian rhythm.

Origin and evolution

Existing mammals are descended from primitive synapsids, a group of amniotic tetrapods that began to flourish in the early Permian, about 280 million years ago, and continued to dominate terrestrial "reptiles" until about 245 million years ago (early of the Triassic), when the first dinosaurs began to emerge. Due to their competitive superiority, the latter made most of the synapsids disappear. However, some survived and their descendants, the mammaliaforms, later became the first true mammals towards the end of the Triassic, about 220 million years ago.

The oldest known mammals are, on the one hand, the multituberculates and on the other, the australosphenids, groups that date from the Middle Jurassic.

However, it should be noted that the Mamalian organization, after initial success during the Permian and Triassic, was almost completely supplanted, in the Jurassic and Cretaceous (for about 100 million years), by the diapsid reptiles (dinosaurs, pterosaurs, crocodiles, plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs, and pliosaurs), and it was not until the meteorite strike that caused the Cretaceous-Tertiary mass extinction that mammals diversified and attained their dominant role.

Taking advantage of resources without having to compete with larger animals meant adapting to inhospitable regions with a normally cold climate, to nocturnal habits, also with low temperatures and poor lighting.

Throughout the evolutionary history of mammals, a series of events occurred that will determine the acquisition of the traits that characterize the class. The homeothermic capacity, that is, to regulate their body temperature, is undoubtedly the characteristic that allows mammals a world free of competition and rich in highly nutritious resources. It was thanks to her that they were able to conquer cold territories and, above all, develop a nocturnal activity.

The growth of hair protecting their bodies from heat loss and the development of vision suitable for low light levels were the other two circumstances that contributed to the conquest of these ecological niches until now free of higher animals. The adaptations of the skeleton were the first step to achieve greater energy effectiveness based on the increase in the use of resources and the reduction of spending.

The skull becomes more effective, loses mass, maintains resistance and simplifies structures while allowing muscular development and effectiveness as well as cerebral (brain) growth and greater intelligence. The modifications of the skull also entail the formation of a secondary palate, the formation of the bone chain of the middle ear and the specialization of the dental pieces. The jaw is formed from a single bone (the dental) and this is the main characteristic to determine if the fossil of an animal belongs to the class of mammals, due to the usual loss of soft tissues during fossilization.

The limbs gradually stop articulating on both sides of the trunk to do so below. In this way, while the mobility of the animal increases, energy expenditure decreases by lowering the requirements for movement and maintenance of the upright body. For its part, the internal gestation of the pups and providing them with food for their first age without having to look for it (milk), allowed greater freedom of movement for the mothers and with it an advance in their survival capacity, both individually and as a whole. of the species.

In all these evolutionary changes, each and every one of the organic structures were involved, as well as the physiological processes. The specializing biological machinery required greater effectiveness of the respiratory and digestive processes, causing the improvement of the circulatory and respiratory systems in relation to physiological effectiveness, and that of the digestive system to achieve a greater nutritional use of food were other achievements achieved by these animals during their evolution.

The central nervous system was acquiring a size and histological structure that is not known in other animals, and the deficiency of lighting faced by nocturnal species was compensated with the development of other sensory organs, especially hearing and the smell. All these evolutionary phenomena took several hundred million years, after which mammals have come to dominate life on Earth.

Summary Cladograms

Phylogeny among extant groups

Genetic studies reveal the following phylogenetic relationships for mammals with respect to other living tetrapods (including protein sequences obtained from Tyrannosaurus rex and Brachylophosaurus canadensis). Mammals constitute the basal amniote group, as they diverged from reptiles and birds in the mid-Carboniferous.

| Tetrapoda |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The phylogeny between extant orders is as follows according to recent genetic studies (including protein sequences obtained from the meridungulates Toxodon and Macrauchenia):

| Mammalia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Phylogeny with fossils

The following cladogram shows the phylogenetic relationships of mammals to some of their ancestors:[citation needed]

| Tetrapoda |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The phylogenetic relationships between the main groups of mammals are, according to the Tree of Life Web Project, the following:

| Mammalia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Classification (systematics and taxonomy)

Classical taxonomy has been based fundamentally on morphological data to establish similarities and differences in order to classify the different species, but new paleontological discoveries and continuous advances in genetics and molecular biology call into question many of the evolutionary theories to date. moment accepted.

As a cladistic summary of what is exposed in the main article, the following tree can be used, in which only taxa of different rank appear directly related to the class Mammalia or pending a more precise hierarchy:

Relationship between humans and other mammals

Negatives

Sometimes, and other times due to unfounded fears, there are many species of mammals considered negative by humans.

Some species of mammals feed on grain, fruit, and other plant products, taking advantage of human crops for food.

For their part, carnivores can generally pose a threat to the lives of livestock and even humans.

Other mammals inhabit urban and suburban areas, causing some considerable problems for the population: car accidents, breakage and deterioration of material goods, infectious and parasitic pests, etc. It should be noted that in this group we include both wild or semi-wild animals and domestic ones.

Kangaroos in Australia, raccoons in North America or foxes and wild boars in Mediterranean Europe illustrate some examples of situations of real or potential danger to populations, but also diseases such as rabies, bubonic plague, tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis or leishmaniosis are closely linked to other mammalian species, usually in close contact with humans.

Furthermore, domestic animals, especially species introduced into new ecosystems, have caused and are causing true ecological tragedies in the local flora and fauna, which indirectly has a negative impact not only on humans, but on other species living on the planet, both animal and vegetable. On numerous oceanic islands, the introduction of domestic animals such as dogs or cats, goats or sheep has led to the total or partial disappearance of numerous species.

Positive aspects

Mammals are an important economic resource for humans.

Many species have been domesticated to obtain food resources from them: milk from cows, buffaloes, goats and sheep, the meat of these species and others such as pigs, rabbits, horses, capybaras and other rodents and even the dog in certain regions of Southeast Asia.

Others, to use them for transport or for work that requires strength or another quality that man does not have: equines such as donkeys, horses and their hybrid mules, camelids such as llama or dromedary, bovids such as the ox or the yak, the Asian elephant or the dogs that pull sleds are some of these examples.

However, before achieving this superiority, early mammals may well have had to become nocturnal to avoid competition with dinosaurs. And it is likely that, to survive the cold of the night, they began to develop endothermy, that is, the internal self-regulation of body temperature —commonly called "warm blood"—, thanks to the appearance of hair and sebum that covered it. waterproofs (the secretion of the sebaceous glands), and sweat from the sweat glands. Once endothermy was acquired, the first true mammals improved their competitive capacity against other terrestrial tetrapods, because their continuous metabolism allowed them to face the rigors of the climate, grow faster and be more prolific. In addition to the skeletal characteristics and others already mentioned —presence of hair and skin glands— that earned them predominance on earth from the Paleocene, mammals present other less distinctive characteristics.

From others, fibers and leather are obtained for the manufacture of clothing, footwear and other utensils: the wool of sheep, alpacas, llamas and goats, the leather of cattle slaughtered for consumption, or that of fur animals bred in captivity for Such an end can serve us as some of these cases.

Other mammals are domesticated to be companion animals. The dog is undoubtedly the closest to man in most parts of the planet and the most versatile (herding, rescue, security, hunting, show,...). But others like the cat, the hamster, the guinea pig, the rabbit, the ferret, the shorttail, and some primates are among the most widespread pets throughout the world.

Hunting is another activity from which humans benefit from mammals. From the beginning of humanity to the present day, hunting has been and still is in some human societies an important food resource.

Animals are also domesticated for recreational or sporting activities: horse riding involves taking advantage of one of the best-known and most appreciated species of mammals by almost all cultures and civilizations: the horse (Equus caballus).

Circuses and zoos are also two enterprises in which man benefits from mammals and other animals.

Some wild mammals also provide a direct benefit to humans without their involvement at all. Bats, for example, are a great ally against insect pests in crops or populated areas, thus also controlling the vectors of certain infectious and parasitic diseases that would put the health of populations at serious risk.

Conservation

In the last half millennium, more than 80 different species have become extinct. The overexploitation of the land, the destruction of the habitat, the fragmentation of the territories through which they are distributed, the introduction of exotic species and other pressures exerted by man threaten mammals around the world.

Currently, the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) considers around 1,000 more species at risk of extinction.

Some factors that contribute to the extinction of species are:

- There are species that are rare by nature, and their low number of specimens is an important risk factor.

- Also those in need of wide territories are threatened, in this case by the loss of land free from human performance and the fragmentation of territories, such as the Iberian lynx.

- Any species that poses a risk to humans or their interests is seriously threatened by the harassment and persecution they are subjected to. Tibetan was an example of these species.

- Wild species that are exploited as food or economic resources by man are usually at critical levels, such as whales and rhinoceros.

- Of course, climate change that modifies habitat is a risk, not only for mammals, but for the entire life on the planet.

Contenido relacionado

Rapid eye movement sleep

Pheromone

Sehima