Luis Bunuel

Luis Buñuel Portolés (Calanda, February 22, 1900-Mexico City, July 29, 1983), known as Luis Buñuel was a Spanish film director, who after the exile of the Spanish civil war was nationalized Mexican. He has been widely considered by many film critics, historians and directors as one of the greatest and most influential filmmakers of all time.

Despite the cinematographic milestones achieved in his native country with Viridiana (1961) and Tristana (1970), the vast majority of his work was made or co-produced in Mexico and France, due to their political convictions and the difficulties imposed by Franco's censorship to film in Spain.

Biography

Early Years

He was born in the Teruel town of Calanda on February 22, 1900. His father, Leonardo Manuel Buñuel González, originally from the same town, was a soldier in Cuba and owned a hardware store and a shipping company, for which he obtained a considerable fortune. After the Spanish-American War, he liquidated his businesses and returned to his hometown, where he married on April 10, 1899, María Portolés Cerezuela, seventeen years old, twenty-eight years his junior, with whom he had seven children: Luis (1900), María (1901), Alicia (1902), Concepción (1904), Leonardo (1907, pediatrician and radiologist), Margarita (1912) and Alfonso (1915), the latter an architect and designer with artistic concerns who stood out as an author of surreal collages.

Three years after the birth of their eldest son, the family moved to Zaragoza and from then on they divided their vacations between Calanda (where they returned at Easter and for the summer) and sometimes to San Sebastián. On one of these occasions, when he was sixteen years old, he was introduced to a very young Concha Méndez at a dance, two years older than him, and who at that time also spent her summers in San Sebastián, with whom he began an engagement that would last seven years.. This is how the writer from 1927 puts it on record in some recordings recorded in 1981 deposited in the music library of Mexico: "One summer in San Sebastián, I met an Aragonese boy who introduced me, at one of the dances, to another boy, who It turned out to be Luis Buñuel, the film director. At that time he was only interested in insects. And we got into relationships. (...) We were together for seven years." A relationship about which we know few details because Buñuel always kept her in the dark and refused to allow Concha to meet all her friends, as she herself continues to recount in the recordings: "We never met together with the boys from the Student's residence. (...) he told me about them, but he never introduced them to me. He asked me how I could reconcile both worlds; one more frivolous, our life together, and the other artistic, in which surreal traits were already filtering."

Luis spent his entire childhood and adolescence in Zaragoza, where he attended primary and secondary education, first at Corazonistas (with a French majority) and in 1908, for seven years, at the Jesuit school in El Salvador, at the beginning of the walk of the Constitution, where today the main headquarters of Ibercaja are located, near the Plaza de Aragón; as a half-board student, he did not wear the full uniform of the boarders, but only the cap with a braid. His grades were generally excellent.

What is known about the first films he saw comes from Buñuel's own statements, and they are imprecise and contradictory. In 1975 he told Pérez Turrent and José de la Colina that he had seen as a child "talking and colored cinema, in the Coine [sic] room, in Zaragoza", alluding to the talking cinema that Ignacio Coyne Lapetra ran between 1905 and 1909.; he recalled a film where “a pig, wearing a police commissioner's sash and top hat, was seen singing a song. It was a cartoon with very bad colors that came out of the figures, and the sound came from a gramophone", but he also told the same authors that in the first film he saw there was a bloody murder. On the other hand, in his memoirs, entitled My Last Sigh, stated that in 1908 he attended the Farrucini [sic] cinema for the first time, which refers to the New Metensmograf Cinematograph Farrusini fair booth of the Barcelona fairground trader Enric Farrús, who settled in Zaragoza in 1908 during the Spanish-French Exhibition of that year that commemorated the centenary of the sites of Zaragoza. He also remembered having seen at that time many funny films by André Deed, who in Spain was known as Toribio, and Georges Méliès's A Trip to the Moon .

In Calanda he gave performances with a theater of cardboard characters that his parents had bought in Paris and shadow play shows with a magic lantern. She regularly went to the theater and the opera, since the Buñuels had, as a wealthy family that they were, a paid box in the Principal, one of the four that then existed in the Aragonese capital. Her nanny also took him to the Circo theater that offered comedies, detective dramas, melodramas, farces, skits, and zarzuelas; Possibly there she would contemplate an operetta based on The Children of Captain Grant , which Buñuel had as one of his best memories, due to the spectacular scenery of him. Already as a teenager, in 1915, he attended numerous theater and opera performances at the Teatro Principal La vida es sueño, El mayor de Zalamea, Don Álvaro o la Force of Fate, La Favourite, Lucia of Lammermoor, Gounod's Faust, Rigoletto, The Barber of Seville, Carmen...

From the age of ten or twelve he began playing the violin and studying it from the age of thirteen. The following year he left Aragon for the first time and traveled to Vega de Pas (Cantabria) and San Sebastián, where he often spent the summer. In 1915 he was expelled from the school by the Jesuits and enrolled in the Zaragoza Institute of Media Education (later called "Goya") as a free student. At that time he read Darwin's The Origin of Species, as well as books from his father Leonardo's extensive library, such as Romain Rolland's Jean-Christophe, works by the French freethinkers Rousseau, Diderot or Voltaire and Spanish classics such as Quevedo or Benito Pérez Galdós, as well as detective novels (Nick Carter, Dick Turpin) and a novel that will leave a mark on him: Robinson Crusoe.

Youth. Madrid and the Student Residence

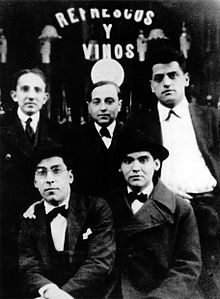

At the age of seventeen, after finishing high school, he left for Madrid to pursue university studies. In the capital he stayed in the recently created Student Residence, founded by the Board for the Extension of Studies, heir to the spirit of pedagogical krausism and the Free Institution of Education, where he stayed for seven years. His purpose, induced by his father, was to study Agricultural Engineering. At this time he became interested in naturism and led a Spartan diet and clothing, liking to wash in ice water. He took part in the activities of the Residencia's film club and became friends, among others, with Salvador Dalí, Federico García Lorca, Rafael Alberti, Pepín Bello and Juan Ramón Jiménez. He also participated in the ultraist gatherings and, every Saturday from 1918 to 1924, in those at the Café Pombo, directed by Ramón Gómez de la Serna.

In 1920, he began studying entomology with Dr. Ignacio Bolívar, which he abandoned to enroll in Philosophy and Letters, a branch of History, since it had been reported that several countries offered work as a Spanish reader to graduates in Philosophy and Letters, which was an opportunity to fulfill his desire to leave Spain.

He did his first staging rehearsals with his colleagues from the Residencia, with delirious versions of Don Juan Tenorio in which Lorca, Dalí and other colleagues acted.

In 1921 he visited Toledo for the first time, a city that made a deep impression on Buñuel and his friends. During these years, he was also aware of the most important international trends in thought and art, and showed interest in Dadaism and the work of Louis Aragon and André Bretón. And, of course, he continued to regularly attend the movies.

Since 1922 he has been writing poems, poetic prose and short stories in various literary magazines of the time, mainly those that served as a vehicle for ultraism and the generation of '27, such as Vltra, Horizonte, Alfar, Helix or The Literary Gazette. His first film projects are also from this time. In 1926, the Junta Magna del Centenario de Zaragoza commissioned him to make a film about the painter Francisco de Goya. The script was finally rejected by the Board, citing economic issues. In 1927 Buñuel proposed to Ramón Gómez de la Serna to make a film. This would be inspired by eight stories by the writer, which would be linked through different news items published in a newspaper read by the protagonist.

In 1923 his father died in Zaragoza, he began his military service and published his first article, which was followed by stories and poems in avant-garde magazines and he even prepared a book that compiled them under the title An Andalusian dog. Many of the images of his writings from these years, prior to French surrealism, went to his cinema. On Saint Joseph's Day of that same year, 1923, he founded the parody Order of Toledo and named himself constable. To be a gentleman you had to get drunk and spend the whole night without sleeping. To it belonged, among others, Dalí, Pepín Bello, Alberti...

In 1924, the year in which Dalí painted his first portrait of him, he graduated in History and gave up his doctorate, determined to go to Paris, which at that time was the cultural capital of the West.

Paris and surrealism

In January 1925, after attending the lecture given by Louis Aragon at the Student Residence, Buñuel left Madrid for Paris. In the French capital he attended the gatherings of the Spanish immigrants and is getting closer and closer to the surrealist group. His fondness for cinema intensified and he regularly saw three films a day, one in the morning (usually private screenings, thanks to a press pass), another in the afternoon at a neighborhood cinema, and another at night.

The pianist Ricardo Viñes proposed the stage direction of El retablo de Maese Pedro, by Manuel de Falla, which, premiered in Amsterdam on April 26, 1926 and also performed the following day, meant a major success. This experience led him to write an avant-garde chamber theater piece entitled Hamlet in 1927, which was staged at the Café Sélect in Paris.

His total conversion to film came after seeing the film The Three Lights (Der müde Tod), by Fritz Lang. Several weeks later, the well-known French film director Jean Epstein appeared on a set and offered to work at any job in exchange for learning everything he could about cinema, and Epstein ended up allowing him to serve as assistant director on the set. from his silent films Mauprat (1926) and The Fall of the House of Usher (La chute de la maison Usher), from 1928.

He began to collaborate as a critic in several film and art publications, in which he recorded his initial cinematographic conceptions, such as the French Cahiers d'Art and the Spanish La Gaceta Literaria, of which he was director of its film section from 1927. The director of this magazine, Ernesto Giménez Caballero, proposed that he found a film club in the Student Residence. The idea was carried out and Buñuel, traveling occasionally to Madrid, promoted avant-garde cinema and surrealist ideas in Spain.

In these years he also collaborated as an actor in small roles, such as the smuggler in the film Carmen (Jacques Feyder, 1926) with Raquel Meller, and in La sirène des tropiques (Henri Étiévant and Mario Nalpas, 1927) with Joséphine Baker. All this background familiarized him with the film business and allowed him to meet good professionals and actors who would later collaborate with him on Un perro andaluz and La edad de oro , the first two films of him. As a critic, he praised Buster Keaton's cinema and attacked the French film avant-garde, in whose ranks Jean Epstein himself was a member, as pretentious. His break with it is well known when the Aragonese refused to work on the new project of the most renowned of the French avant-garde directors, Abel Gance, of whose Napoleon Buñuel had recently written a harsh criticism.

Increasingly interested in Breton's surrealist group, he began to convey the news of this trend to his colleagues at the Student Residence, writing poems of an orthodox surrealism and urging Dalí to move with him to Paris to discover the new movement In 1927 he wrote a book of surrealist poetry, which he never edited, whose title was initially Polismos and later Un perro andaluz , which was what he would later receive. his first movie.

In 1928 he prepared a film script about Francisco de Goya on the occasion of the centenary of his death, sponsored by a commission from Zaragoza. The project did not come to fruition due to lack of budget, nor did another based on a script by Ramón Gómez de la Serna that was going to be titled The world for ten cents, in which the common thread was to be the successive changes of owner of a coin, or, different narrations that were found in a newspaper. Gómez de la Serna finally sent him the script for Caprichos (his new title), although it has not been preserved, since between October and November of that year he would abandon the project when he began working with Dalí on the of An Andalusian dog.

Un chien andalou and L'Âge d'or

In January 1929, Buñuel and Dalí, in close collaboration, finalized the script for a film whose project would successively be titled The Marist on the Crossbow, It's Dangerous to Look Inside and, finally, Un perro andaluz, once the publication with this title of his projected surrealist collection of poems was rejected. The film began shooting on April 2 with a budget of 25,000 pesetas contributed by Buñuel's mother. It premiered on July 6 at the Studio des Ursulines, a Parisian film club, where it achieved resounding success. among the French intelligentsia, and ran for nine consecutive months at Studio 28.

From the screening of Un chien andalou, Buñuel was fully admitted to the surrealist group, which met daily at the Café Cyrano to read articles, discuss politics and write letters and manifestos. There, Buñuel forged friendships with Max Ernst, André Breton, Paul Éluard, Tristan Tzara, Yves Tanguy, Magritte and Louis Aragon, among others.

At the end of 1929, he met again with Dalí to write the script for what would later be L'Âge d'or, but the collaboration was no longer so fruitful, because between the two stands the great love of Dalí, Gala Eluard. Buñuel began shooting the film in April 1930, when the painter was enjoying a vacation with Gala in Torremolinos. When he discovered that Buñuel had already finished the film with the substantial patronage of the Viscounts of Noailles, who wanted to produce one of the first sound films in French cinema, Dalí felt left out of the project and betrayed by his friend, which caused a rift between them that it increased in the future. Despite that, he congratulated Buñuel on the feature film, assuring that he had found it "an American film." The premiere took place on November 28, 1930. Five days later, far-right groups attacked the cinema where it was being shown, and the French authorities banned the film and seized all existing copies, beginning a long censorship that would last for half a century. it would not be distributed until 1980 in New York and a year later in Paris.

Hollywood and the Madrid of the Republic. The Hurdes

In 1930, Buñuel traveled to Hollywood, hired by Metro Goldwyn Mayer, as an "observer", in order to familiarize himself with the American production system. There he met Charlie Chaplin and Sergei Eisenstein. In 1931 he arrived in Spain, on the eve of the proclamation of the Second Republic. The Golden Age was screened in Madrid and Barcelona. In 1932 he attended the first meeting of the Association of Revolutionary Writers (AERA), broke away from the Surrealist group, and joined the French Communist Party. Hired by Paramount, he returned to Spain and worked as a synchronization manager.

In April 1933, financed by his friend Ramón Acín, he began filming Las Hurdes, tierra sin pan, a documentary about that region of Extremadura. The right wing and the Spanish Falange began to rebel and the film was censored by the Second Republic for considering it denigrating Spain. That same year he signed a manifesto against Hitler with Federico García Lorca, Rafael Alberti, Sender, Ugarte and Vallejo.

In 1934, he visited Dalí in Paris, already married to Gala. Dalí was indifferent to Buñuel, which increased his distance from him. On June 23, he married Jeanne Rucar, whom he had met at the home of his friend Joaquín Peinado in 1925 when he was studying anatomy in Paris, and who had been a bronze medalist in artistic gymnastics at the 1924 Paris Olympics. The wedding It was held in the XX district town hall of the French capital, without inviting the family, with three impromptu witnesses (one of them, an unknown passerby) and, after lunch, Buñuel returned to Madrid, since he had agreed to work for the Warner Brothers as dubbing director. The couple would have two children, Jean Louis, born in Paris, and Rafael, who would be born in New York.

In 1935, with the help of some family money, together with Ricardo Urgoiti, he founded the Filmófono production company, which competed with the Casanova brothers' Cifesa, the main Spanish production company of the 1930s. Filmófono produced films such as Don Quintín el amargao, where the great bailaora Carmen Amaya made her film debut, Juan Simón's daughter, Who loves me? or ¡Sentinel alert!, and Buñuel's only condition for producing them was, curiously, not to appear on the technical sheet, since in his eyes they were nothing more than "cheap melodramas& #3. 4;. All these feature films were profitable and represented the consolidation of the Spanish film industry in the thirties. However, the Civil War aborted this project.

The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939)

The coup d'état of July 1936 surprised Buñuel in Madrid. Just as Dalí aligned himself with Franco and sympathized with the rebel side, Buñuel always remained faithful to the Second Republic. However, he did not stop helping his friends on the Francoist side when they were in danger of death; Thus, he managed to get José Luis Sáenz de Heredia (first cousin of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of the Falange, who sympathized with Franco, since they had worked together at Filmófono, released. On August 18, 1936, Lorca was assassinated.

In September 1936 he left Madrid on a crowded train for Geneva, via Barcelona. There he had been summoned for an interview by Álvarez del Vayo, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic, who sent him to Paris as a trusted man of Luis Araquistáin, ambassador to France, to carry out different missions, mainly intelligence. He supervised and wrote with Pierre Unik the documentary Loyal Spain in Arms . He made his air baptism in several lightning trips to Spain, on war missions.

During 1937, he was in charge of supervising the Spanish pavilion at the International Exposition in Paris for the Republican government. Dalí painted the second and last portrait of him: The Dream. On September 16, 1938, helped with the travel expenses by his friends Charles de Noailles and Rafael Sánchez Ventura, he traveled to Hollywood again, this time commissioned by the Republican Government to supervise, as technical and historical adviser, two films about the Civil War that were going to be shot in the United States.

In 1941, after the war was over, when filming began on Cargo of Innocents, the General Association of American Producers banned any film against Franco, which meant the end of the project in the that Buñuel was involved. Jobless and with little money, and with his wife and children reunited with him, he accepted the assignment offered to him by the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York, as associate producer for the documentary area and supervisor and chief editor of documentaries for the Coordination of Inter-American Affairs, directed by Nelson Rockefeller. His mission was to select anti-Nazi propaganda films; he had his own personal office in charge of him. His first work for MoMA consisted of the reissue of The Triumph of the Will , by Leni Riefenstahl, in order to make it shorter and more accessible to members of the United States Government so that they could see the potential of cinema as a propaganda tool. But he was fired in 1943 following the publication of the book The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí , where the painter branded Buñuel an atheist and a man of the left. A journalist from the Motion Pictures Herald attacked Buñuel in an article where he warned about how dangerous the presence of this Spaniard was in such a prestigious museum. Buñuel met with Dalí in New York to ask him for explanations and that interview meant the break in their relations.

He returned to Hollywood and went to work for Warner Brothers as head of dubbing for Spanish versions for Latin America. After the collaboration with Warner in 1946, he stayed in Los Angeles in search of a job related to the cinema and waiting to be granted US citizenship, which he had applied for.

Mexican stage

When Luis Buñuel was still living off the money he had saved the previous year, it happened that he met Denise Tual, the widow of Russian actor Pierre Batcheff (leader of An Andalusian dog, who had committed suicide in 1932). The woman, who had remarried the French producer Ronald Tual, offered him to work on the new project that she intended to carry out: La casa de Bernarda Alba , which Buñuel would direct. Tual, who had come to Los Angeles with the interest of learning more about the American film industry, had the intention of making the film between Paris and Mexico, for which he took advantage of his return to Paris to make a stopover in Mexico and finalize some business with him. French producer of Russian origin Oscar Dancigers, exiled in that country. Once there they found out that the rights to the work had been sold to another production company that had bid higher.

The project was cut short, Luis Buñuel was lucky that Dancigers offered him another job: directing Gran Casino, a commercial film with the well-known Mexican singer Jorge Negrete and the leading Argentine figure Libertad Lamarque. Buñuel accepted and, once all the residency papers were arranged and installed with his wife and his children, he entered the Mexican film industry. This first film of his new stage was a resounding flop and for the next three years he was forced to support himself on the money his mother sent him every month.

In 1949, when he was about to leave the cinema, Dancigers asked him to take over the direction of El gran calavera, since Fernando Soler could not be both director and protagonist. The success of this film and the granting of Mexican nationality encouraged Buñuel to propose a new project to Dancigers more in keeping with his wishes as a filmmaker, proposing, under the title My little orphan, boss!, a plot about the adventures of a young lottery seller. This offer was followed by a better response from Dancigers, the making of a story about poor Mexican children.

Thus, in 1950 Buñuel made Los olvidados, a film with strong ties to Las Hurdes, tierra sin pan, and which at first the ultranationalist Mexicans did not like (Jorge Negrete the first), since it portrayed the reality of suburban poverty and misery that the dominant culture did not want to recognize. However, the prize for best director awarded to him at the 1951 Cannes Film Festival meant international recognition for the film, and the rediscovery of Luis Buñuel, and the rehabilitation of the filmmaker by Mexican society. Currently, Los olvidados is one of the only three films recognized by Unesco as Memory of the World.

In 1951 he filmed Susana and Him; the latter was a commercial failure but would be valued in the following years. In 1952 he left Mexico City to film Subida al cielo , a simple film where a dream of the protagonist gives the surreal touch of Buñuel and which earned him another visit to Cannes. That same year he filmed Robinson Crusoe, the first film to be shot in Eastmancolor (prints were sent to California every day to check the results), and, along with The Young Woman, which he directed in 1960, one of the only two films he shot in English and with an American co-production. In 1953 he directed The Illusion Travels by Tramcar, one of the films considered "minor"; but because of its freshness and simplicity, and backed by writers like José Revueltas and Juan de la Cabada, it survives over the years.

In 1954 he directed The River and Death and was elected a member of the jury at the Cannes International Film Festival. In 1955, the year in which he filmed Así es la aurora in France (which gives him the opportunity to visit his mother in Pau), faithful to his ideas, he signed a manifesto against the atomic bomb which, together with his support for the anti-fascist magazine España Libre (positioned against the US), led to his inclusion on the US blacklist until 1975. From then on, each time they passed through the US, both he and his family were questioned. However, Buñuel said that the US was the most beautiful land he had ever known.When someone asked him if he was a communist, he always answered that he was a Spanish republican.

After Essay of a Crime (1955), he made Death in the Garden (1956), with a script by Luis Alcoriza and Raymond Queneau, which adapted the novel of the same name of Lacour. The National Film Theater of London held a retrospective of his work. Nazarín (1958), International Award Winner at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival, is the first of the three films he would make with actor Paco Rabal. That same year he shot Los ambicios, a film of political and social commitment. In 1960 he last directed a play, Don Juan Tenorio , in Mexico, and made and premiered in the US La joven .

He was the winner of the National Fine Arts Award, awarded by the Government of Mexico in 1977.

In 1962 he shot The Exterminating Angel, one of his most important and personal films, in which he alluded to several private jokes from his days in the Student Residence and the surrealist period he spent in France.

During this stage, Buñuel and Jean-Claude Carrière were offered to adapt Malcolm Lowry's novel Under the Volcano on two occasions. However, in both the filmmaker and screenwriter turned down the offer after reading the novel and "not finding a movie behind the book".

Spanish stage

In 1960 Buñuel returned to Spain to direct Viridiana, a Spanish-Mexican co-production with a script written with Julio Alejandro. The film was produced by Gustavo Alatriste (on the Mexican side) and by Pere Portabella and Ricardo Muñoz Suay, on behalf of the Spanish production companies UNINCI (Unión Industrial Cinematográfica) and Films 59. It starred Silvia Pinal, Francisco Rabal and Fernando Rey.

Viridiana was entered into competition at the 1961 Cannes Film Festival as the official representative of Spain and won the Palme d'Or, which was received by the then General Director of Cinematography, José Muñoz Fontán. However, after the Vatican newspaper L'Osservatore Romano condemned the tape as blasphemous and sacrilegious, Spanish authorities sentenced it to an 'administrative death'.;, denying him the so-called definitive filming permit, which in turn gave rise to an economic conflict between the Spanish and Mexican producers. Viridiana could not be officially screened in Spain until 1977.

In 1970, Buñuel shot again in Spain, this time as a Spanish-French-Italian co-production; It was Tristana, starring Catherine Deneuve, who had already played the leading role in Belle de jour, and Fernando Rey.

In 1977, Buñuel rounded off his work with Ese obscuro objet de deseo (Cet Obscur Objet du Désir), a Spanish-French co-production partially shot in Spain, which received the special prize from the San Sebastián Film Festival. In the film, which reviews themes previously discussed in Viridiana or Tristana, Carole Bouquet and Ángela Molina play the female character who replicates Fernando Rey together.

In addition to those professional stays in Spain, between the years 1960 and 1980, Buñuel used to spend time in Madrid where he lived in an apartment in the Torre de Madrid. In this building a plaque remembers Luis Buñuel as a "Key figure of the 20th century".

French stage

Already in his Mexican stage, Buñuel had shot several French-produced films after the laudatory European reviews of Ensayo de un crimen, Así es la aurora or Death in the Garden, but his real return to French cinematography came in 1963 with Diary of a Waitress (Le Journal d'une Femme de Chambre), adaptation of the novel by Octave Mirbeau. Thus he begins his cooperation with the producer Serge Silberman and the screenwriter Jean Claude Carrière.

In 1964 he filmed his last Mexican film, Simón del desierto, which did not end as projected due to lack of budget. Even so, he obtained the Silver Lion from the Venice Film Festival in 1965, the year in which, together with Carrière, he prepared the adaptations of The Monk and Là-bas .

In 1966, Dalí telegraphed him from Figueras offering to prepare the second part of An Andalusian Dog. That same year Belle de jour premiered, which won the Golden Lion in 1967 at the Venice Mostra. This film achieved extraordinary public success in France and from then on Buñuel's premieres became cultural events, which motivated Silberman to grant him complete creative freedom and sufficient resources for the production of his films, which characterized the stage end of his work. In 1969 the Mostra awarded him the grand prize of homage for all of his work.

In 1972 he became the first Spanish director to win the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, for The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (Le Charme Discret de la Bourgeoisie), a film that was going to be shot in Spain, which was impossible due to censorship. This film, along with The Milky Way (La Voie Lactée, 1968) and The Phantom of Liberty (Le Fantôme de la Liberté, 1974), make up a kind of trilogy that attacks the foundations of conventional narrative cinema and the cause-consequence concept, advocating the exposure of chance as the engine of behavior and the world. That same year, 1972, he visited Los Angeles, where his son Rafael lived, and George Cukor offered a dinner in his house in honor of Buñuel, which was attended, in addition to his son Rafael and Carrière, by important filmmakers such as Alfred Hitchcock, Billy Wilder, G. Stevens, William Wyler, R. Mulligan, Robert Wise or Rouben Mamoulian.

In 1980 he made his last trip to Spain and underwent prostate surgery. In 1981, fifty years after it was banned, The Golden Age was rerun in Paris, he was hospitalized for gallbladder problems, Agustín Sánchez Vidal published his literary work, the Center Georges Pompidou in Paris organized a tribute in his honor and An Andalusian dog was projected on a screen placed on the roof of this cultural center.

In 1982 he published his memoirs, written in collaboration with Carrière and entitled My Last Breath.

Death

Luis Buñuel died in Mexico City on July 29, 1983 at dawn, due to liver and kidney disease caused by cancer. His last words were for his wife Jeanne: & # 34; Now I really die & # 34;. That same year he had been named doctor honoris causa by the University of Zaragoza. He remained faithful to his ideology until the end: there was no farewell ceremony, being in 1997 when his ashes were finally scattered on Mount Tolocha, located in his hometown, Calanda.

Recurring collaborations

Throughout his career, Buñuel collaborated with great artists from Mexico, Spain and France.

| Actor | An Andalusian dog (1929) | The golden age (1930) | The Huerdes, land without bread (1933) | Grand Casino (1947) | The big skull (1949) | The forgotten (1950) | Susana (1951) | The daughter of deceit (1951) | Up to the sky (1952) | A woman without love (1952) | Gross (1953) | He (1953) | The river and death (1954) | The illusion travels in tram (1954) | Robinson Crusoe (1954) | Abismos of Passion (1954) | Cream testing (1955) | That's the aurora. (1955) | Death in this garden (1956) | Nazareth (1959) | The ambitious (1959) | The young (1960) | Viridiana (1961) | The exterminating angel (1962) | Journal of a prisoner (1964) | Simon of the desert (1965) | Belle de jour (1967) | The dairy way (1969) | Tristana 1970) | The discreet charm of the bourgeoisie (1972) | The Ghost of Freedom (1974) | That dark object of desire (1977) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michel Picccoli | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Julien Bertheau | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fernando Rey | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Claudio Brook | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Silvia Pinal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Francisco Rabal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lilia Prado | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fernando Soler | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tito Junco | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Catherine Deneuve | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ernesto Alonso | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rita Macedo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Delphine Seyrig |

Filmography

As director

Between 1929 and 1977 he directed a total of thirty-two films. In addition, in 1930 he shot Menjant garotes ("Eating hedgehogs"), a silent film of only four minutes, with the Dalí family as the protagonist.

- An Andalusian dog (A chien andalou1929).

- The golden age (L'âge d'or, 1930).

- The Hurdes, land without bread (The Hurdes1933).

- Grand Casino (In the old Tampico1947).

- The Great Skull (1949).

- The forgotten (1950).

- Susana (Demon and flesh1951).

- The daughter of deceit (1951).

- A woman without love (When the children judge us1952).

- Up to the sky (1952).

- Gross (1953).

- He (1953).

- The illusion travels in tram (1954).

- Abismos of passion (1954).

- Robinson Crusoe (in 1952 and registered in 1954).

- Trial of a crime (The criminal life of Archibaldo de la Cruz, 1955).

- The river and death (1954-1955).

- That's the aurora. (Cela s'appelle l'aurore1956).

- Death in the garden (Death in this garden, The mort in ce garden1956).

- Nazareth (1958-1959).

- The ambitious (The fever goes up to El Pao, La fièvre monte a El Pao1959).

- The young (The Young One, 1960).

- Viridiana (1961).

- The exterminating angel (1962).

- Journal of a waitress (Le journal d'une femme de chambre1964).

- Simon of the desert (1964-1965).

- Belle de jour (Beautiful day1966-1967).

- The Milky Way (La Voie Lactée1969).

- Tristana (1970).

- The discreet charm of the bourgeoisie (Le charme discret de la bourgeoisie, 1972).

- The Ghost of Freedom (He fantôme de la liberté1974).

- That dark object of desire (Cet obscur objet du désir1977).

Apart from the films he made as a director or actor, or in which he collaborated in one way or another, there were also a number of projects that he was unable to carry out.

As assistant director

- Mauprat (Jean Epstein, 1926).

- La Sirène des tropiques (Mario Nalpas and Henri Étiévant, 1927).

- The maison Usher chute (Jean Epstein, 1928).

As a producer or supervisor

- An Andalusian dog (1929).

- Don Quintin, the bitter (Luis Marquina, 1935).

- The daughter of John Simon (José Luis Sáenz de Heredia, 1935).

- Who loves me (José Luis Sáenz de Heredia, 1936).

- Sentry alert (Jean Grémillon, 1936).

- Spain loyal to arms (Jean-Paul Le Chanois, 1937). Proprietary Documentary also known as Spain 1936 or Madrid 1936.

As a scriptwriter in films not made by him

- If you can't, I can. (Julián Soler, 1950). Guion de Janet Alcoriza based on an argument by L. Buñuel and Luis Alcoriza.

- The monk (Le moine(Ado Kyrou, 1965). Guion de L. Buñuel and Jean-Claude Carrière.

- The midnight bride (Antonio F. Simón, 1997). Guion de L. Buñuel and José Rubia Barcia adapted by Lino Braxe.

As an actor

- Mauprat (Jean Epstein, 1926).

- Carmen (Jacques Feyder, 1926).

- La Sirène des tropiques (Henri Étiévant, Mario Nalpas (co-directors), 1927).

- An Andalusian dog (1929).

- The bitter fruit (Arthur Gregor, 1931).

- The daughter of John Simon (José Luis Sáenz de Heredia, 1935).

- I cry for a bandit (Carlos Saura, 1964).

- In this town there are no thieves (Alberto Isaac, 1964).

- Belle de jour (1967)

- The chute d'un corps (Michel Polac, 1973).

- The Ghost of Freedom (1974).

Literary work

Luis Buñuel made various forays into various fields (theatre, literature and poetry) before and after dedicating himself to the world of cinema, although his most relevant contribution was the surrealist poems and prose written between 1922 and 1929 during his stay at the Residencia de Estudiantes de Madrid. His texts from this period can be inscribed among the most interesting contributions, together with those of Juan Larrea (1895-1980), of the introduction of surrealism as a key component of the Generation of '27. But the texts Literary works from this period are not only influenced by French surrealism, but also reveal the traits of Ramón Gómez de la Serna's greguería and the ultraism of the Madrid avant-garde.

Many of these texts were going to make up a book of surrealist poetic and prose texts about which he has been reporting since 1926 and was initially going to be titled Polismos. Still in 1929, in a letter written to Pepín Bello on February 10, he intended to publish it, although now with the title An Andalusian Dog , which eventually became his first film..

The most significant texts are:

Initial texts

- Unqualified betrayal. Prosa. Publication: Ultra, Madrid, n. 23, February 1, 1922, [p. 4]. First text published by Buñuel.

- The guignol [sic]. Lecture given at the Student Residence on the history of the script as a presentation of a puppet performance by Félix Malleu, possibly on May 5, 1922.

- Instrumentation. Dedicated to musicologist Adolfo Salazar. Definitions of musical instruments of an orchestra influenced by the guild. Publication: Horizon, Madrid, No. 2, November 30, 1922.

- Suburbs. Subtitle "Motives". Prosa. Publication: HorizonNo. 4, January 1923.

- Inadvertent tragedies as themes of a novice theater. Theoria aesthetic of futuristic roots. Publication: AlfarLa Coruña, February 26, 1923.

- Why I don't wear a watch. Subtitles «tale». Prosa. Publication: AlfarNo. 29, May 1923.

- The Blind of Turtle. I count. Published in the Revista Tyflófila Hispano-Americana los Ciegos.

- Theorem. Unpublished Poem written in 1925.

- Lucille and his three fish. Unpublished Poem written in 1925.

- Flood. Poetic prose. Unpublished in 1925.

- Ramuneta on the beach. Poetic prose. Unpublished in 1926.

- Rustic horses. Poetic prose. Written in 1927.

- A decent story. Short story with epilogue titled "Indecent story". Written in 1927.

- The pleasant slogan of Santa Huesca. Surreal tale. Written in 1927.

- Letter to Pepín Bello on the day of San Valero. Dated in Madrid, February 2, 1927. This is a deeply literary letter consisting of a surreal account.

- Story project. 1927. Surrealist narrative outline.

- The Holy Eucharist. 1927. Surrealist narrative outline.

- Menage a trois. 1927. Poetic prose.

- Hamlet. Surrealist theater. Original dated July 1927. Unpublished (according to news from Buñuel to Sánchez Vidal) in the coffee Select of Montparnasse, where it was represented by Francisco García Lorca, Augusto Centeno, Joaquín Peinado, Francisco Bores, Hernando Viñes, José María Ucelay, the son or brother of Darío Regoyos and Luis Buñuel himself in the role of Hamlet.

Texts of the unpublished book An Andalusian dog

The ten poems in the unpublished book, which was initially going to be titled Polismos, were written around 1927. Some were published later.

- I'd like it for me.

- Miraculous polysoir

- It doesn't sound good or bad.

- When we get into the bed

- The rainbow and the cataplasm

- Redentora. Published in The Literary GacetaNo. 50, 15 January 1929, p. 2.

- Bacanal. Published with Redentora in The Literary Gaceta.

- Olor of Holiness. Published in The Literary GacetaNo. 51, February 1, 1929.

- Ice Palace. Published in Helix, Villafranca del Penedés, No. 4, May 1929.

- Bird of distress. Published with Ice Palace in Helix.

Other texts

- A giraffe. Texts written in French for installation. Published in the magazine of the surrealist group Le Surréalisme au Service de la RevolutionNo. 6, May 15, 1933.

- The Poetry Instrument Film. Recorded and transcribed conference in the magazine University of MexicoDecember 1958.

- The Duchess of Alba and Goya. Synopsis written in 1937 for the Paramount in the form of a short account of the script of his project for the centenary of Goya of 1927.

- Lighting around a dead hand. 1944. Original in English. Guion for a sequence of the film The beast with five fingers.

- Unreadable son of flute. Guion of 1947 in collaboration with Juan Larrea for a surreal film project.

- Mon dernier soupir (autobiographie) / My last sighco-written with Jean-Claude Carrière, 1982.

Film criticism

Since 1927, Luis Buñuel directed the film section of the magazine La Gaceta Literaria. In it he wrote several articles, although he also published in French magazines, such as Cahiers d'Art or its supplement Feuilles Volantes .

- "One night in the "Studio des Ursulines", The Literary GacetaNo. 2, January 15, 1927.

- «From the photogenic plane», The Literary GacetaNo. 7, April 1, 1927. Dated in the original in Paris in December 1926.

- «Metropolis», The Literary GacetaNo. 9, May 1, 1927. About the Fritz Lang movie.

- «Napoleon Bonaparte», Cahiers d'ArtNo. 3, 1927. About the Abel Gance movie.

- «When the flesh succumbs», Cahiers d'ArtNo. 10, 1927. About The fate of the flesh (The way of all flesh)Victor Fleming. He hasn't survived any copies of this movie.

- «Sportsman for love», Cahiers d'ArtNo. 10, 1927. About The schoolgirl (College)Buster Keaton.

- «The lady of the camelias», The Literary GacetaNo. 24, December 15, 1927. First number with monographic section of cinema (pages 4-5) directed by Buñuel. Buñuel's critique refers to Fred Niblo's film, Margarita Gautier (Camille)whose premier dates from December 18, 1926, and its marketing of 1927, film lost today, except for very deteriorated and fragmented copies.

- «Variaciones sobre el mustache de Menjou», The Literary Gaceta, n.o 35, 1 June 1928; previously published in French with the title of "Variations sur Menjou", in Feuilles Volantes of Cahiers d'Art1927.

- «Découpage or film segmentation, The Literary GacetaNo. 43, October 1, 1928. Monographic number dedicated to the cinema, where the following three texts were also published.

- "News from Hollywood." The Literary GacetaNo. 43, October 1, 1928.

- «Our poets and cinema». The Literary GacetaNo. 43, October 1, 1928.

- «Juana de Arcoof Carl Dreyer." The Literary GacetaNo. 43, October 1, 1928.

- «The comic in the cinema», The Literary GacetaNo. 56, April 15, 1929.

Awards and distinctions

Contenido relacionado

Prehistoric art

Mere (Maori)

Radiohead