Lucino Visconti

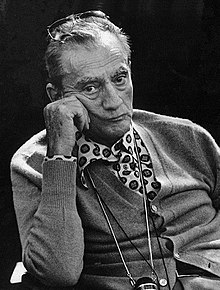

Luchino Visconti di Modrone, Count of Lonate Pozzolo (Milan, November 2, 1906 – Rome, March 17, 1976), was an Italian aristocrat, opera and film director. He has been one of the most internationally recognized contemporary Italian filmmakers.

Biography

Luchino Visconti was born in 1906 in Milan, capital of the Lombardy region in Italy, into one of the oldest families of the Lombard aristocracy, the Visconti, whose lineage dates back to the Middle Ages. He was the son of Duke Giuseppe Visconti di Modrone and Carla Erba, daughter of a powerful Milanese industrialist.

From a very young age, he was linked to the La Scala theater in Milan, turning opera into one of his passions, a means of artistic expression with which his grandfather, Duke Guido Visconti, and his uncle Huberto Visconti maintained a close relationship, since both were sovrintendenti (superintendents) of the La Scala theatre.

Cinema career

Obsession, La terra trema and Senso

In 1935 he moved to Paris, where, thanks to Coco Chanel, he became linked and collaborated with the French filmmaker Jean Renoir, with whom he participated as an assistant director on Los Bajos Finos (1936) and as an assistant and costume designer in A Country Game (Une Partie de Campagne) (1937).

His work then approaches the artistic principles of neorealism. Obsession (from 1943) was the first neorealist film, a movement that takes the novelist Giovanni Verga as its predecessor; He introduced a new vision of cinema, of directing actors (frequently non-professionals) and in the conception of reality and social problems. Neorealism was not a school with entirely consistent principles and artistic personalities, neither in the directors nor in the scriptwriters, hence the existence of a more idealistic line, represented by Roberto Rossellini, and another, closer to Marxism or to related social conceptions, represented precisely by Visconti, among others.

One of the most important Marxist theorists of neorealism was Guido Aristarco, author of The dissolution of reason —discourse on cinema—, who considered that The earth trembles (La terra trema, from 1948) was the most successful and ideologically and aesthetically advanced film, which undertook a search for man before things that did not subject them to them as permanent by themselves, which would constitute an alienation, and that also did not admit an immutable human nature (Visconti's anthropomorphic cinema).

With Obsession in 1943, a film with a strong Renoirian influence, Visconti dealt with subjects not acceptable until then by the fascist censorship based on a novel by James M. Cain, The Postman Calls twice, narrating the murder of a man committed by his wife's lover. What most impacted the Italian society of the time, beyond the excellent direction of the actors and the meticulousness of the style, was the climate of oppression and the sordid environment that was perceived in the film, despite having no apparent political implications.

The years that followed his second production, The Earth Tremble (La terra trema, 1948), found Visconti committed to the anti-fascist struggle and the Italian resistance. The harsh living conditions of the fishermen, peasants and workers in southern Italy captured his attention, and served as an inspiration for his new film, which was an economic failure, but placed Visconti at the top of the political and social scene of the time, because of the moral and human commitment that he had faced.

In the 1950s, after filming Bellissima, starring Anna Magnani, a melodrama set in the world of cinema, Visconti addressed the issue of the Risorgimento and Italian unity with Senso, a love story set in the most dramatic moments of the Risorgimento and a critical vision that once again paved the way for censorship to be imposed with all its force. This totalizing conception of the Risorgimento was completed with the inclusion of an important cultural aspect: an opera by Verdi and the spirit of Verdi melodrama as the core of the film.

Rocco and his brothers, and El Gatopardo

After an incursion into creative cinema with the free adaptation of a work by Dostoevsky, The White Nights, Visconti returned to the path of films filled with social questions, with the film Rocco and his brothers (1960). He once again addressed the issue of the conflicts suffered by the southern peasants, this time within the framework of the story of a family that moves to Milan and the harsh reality that they must face there.

The importance that Visconti gave to the nuclear family in the context of his films is also revealed in other films.

In El gatopardo, his next film, he materialized the signs of great production evidenced in his previous film. In it, with great visual beauty and based on the book by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, he reflected Prince Di Salina's reflections on the decline of his noble class and his dying world, while the new bourgeoisie rose to economic and political power in the frame of the events that shook Sicily in 1860 (the invasion of the red shirts led by Giuseppe Garibaldi).

Towards a cinema with a historical perspective

Indecent atavism or Sandra (Vaghe stelle dell'Orsa in the original) in 1965 was a free adaptation of Sophocles' Electra and continued to use Claudia Cardinale as his fetish character —it was also a new essay in his interiority cinema— and The Stranger —a faithful reproduction of the novel by Albert Camus—, in 1967, served as a prelude to The Fall of the gods, a metaphor for evil and the moral corruption of a German family linked to Nazism during World War II.

The Fall of the Gods realistically and harshly reflected a dark period in the history of mankind, and was hailed by critics as a film of brilliant historical detail.

Death in Venice was considered one of the most important films of the 70s, its fundamental content being the contradiction between the artist —the film's protagonist— and his bourgeois position.

Ludwig (about Ludwig II of Bavaria) meant a coherent continuation of the previous production, that is, a reflection on the relationships between life and art, between aesthetics and ethics.

In 1974 he directed Confidences or Family Portrait in the Interior (Gruppo di famiglia in uno interno), Visconti declaring that it was an anti-fascist film in the critical and broad sense of the term. A twilight portrait of the inability of the coherent intellectual to face his social group and to adapt to a world of banal cultural values, with which Visconti saw himself very much reflected, although the main character was a transcript of the art critic Mario Praz.

Shortly before his death, and in a rather serious state of health, he managed to make his last film, The Innocent, an adaptation of the homonymous novel by Gabriele D'Annunzio.

His death occurred on March 17, 1976 in the city of Rome, when he was 69 years old.

The artistic collaboration between Visconti and various colleagues (Claudia Cardinale, Alain Delon, Burt Lancaster, Nino Rota, Silvana Mangano, Suso Cecchi D'Amico, Alida Valli, Dirk Bogarde, Anna Magnani, Rina Morelli, Paolo Stoppa, Giorgio Albertazzi, Anna Proclemer and others) adds prestige to the work of one of the most important film and opera directors of the XX century who, along with directors Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Roberto Rossellini, Mauro Bolognini, and later Pier Paolo Pasolini, Bernardo Bertolucci, Vittorio de Sica or the Taviani brothers, placed Italian cinema in a position of honor.

His works conducting opera

Opera was Visconti's first love and the genre framed or featured conspicuously in several of his performances such as Senso, The Leopard and Ludwig, which tells of the Bavarian king's obsession with the music of Richard Wagner. The title The Fall of the Gods alludes to Wagner's opera of the same name, drawing a parallel between Wagner and Nazi Germany.

On the Milanese operatic stage he brought his hometown theater, La Scala, to a new splendor with his magnificent stagings of La Traviata, Anna Bolena, Iphigenia in Táuride and La Sonnambula for Maria Callas.

He worked at La Scala, the Paris Opera and Covent Garden in London in a memorable production of Verdi's Don Carlos with Jon Vickers. Apart from Callas, his greatest collaborators were Leonard Bernstein, Carlo Maria Giulini and Franco Zeffirelli, his most famous disciple.

In Death in Venice music was once again present in the figure of the tortured composer. The film is largely responsible for the current popularity of the music of Gustav Mahler whose Adagietto from the Fifth Symphony frames each scene.

Filmography

- 1943 — Obsession (Ossessione)

- 1945 — Giorni di glory (documentary)

- 1948 — The earth trembles (The terra trema)

- 1951 — Appunti his a fatto di cronaca (documentary)

- 1951 — Beautiful (Bellissima)

- 1953 — We women (Siamo donne. Episode: Anna Magnani)

- 1954 — Senso (Senso)

- 1957 — White nights (I noticed him bianche)

- 1960 — Rocco and his brothers (Rocco e i suoi fratelli)

- 1962 — Boccaccio 70 (Boccaccio '70. Episode: Work [chuckles]Il lavoro])

- 1963 — The catpardo (Il gattopardo)

- 1965 — Sandra (Vaghe stelle dell'Orsa...)

- 1967 — The witches (Le streghe. Episode: The burnt witch alive [chuckles]The Live Witch Straits])

- 1967 — Foreign (Straniero)

- 1969 — The Fall of the Gods (The caduta degli dei)

- 1970 — Alla ricerca di Tadzio (documentary)

- 1971 — Death in Venice (Die to Venezia)

- 1973 — Luis II de Baviera (Ludwig)

- 1974 — Confidences (Inner Family Portrait) (Gruppo di famiglia in an intern)

- 1976 — The innocent (L'innocente)

Trajectory in theater

Prose Theater Director

- Parenti terribili of Jean Cocteau (1945)

- Fifth colonnade of Ernest Hemingway (1945)

- The macchina da scrivere of Jean Cocteau (1945)

- Antigone of Jean Anouilh (1945)

- A porte chiuse by Jean-Paul Sartre (1945)

- Adamo by Marcel Achard (1945)

- La via del tabacco John Kirkland (1945)

- Il marriage di Figaro by Pierre Augustin Caron De Beaumarchais (1946)

- Delitto and punishment by Gaston Bary (on the work of Dostoievski) (1946)

- Zoo di vetro of Tennessee Williams (1946)

- Euridice of Jean Anouilh (1947)

- Come vi piace by William Shakespeare (1948)

- A tram che si chiama desiderio of Tennessee Williams (1949)

- Oreste Vittorio Alfieri (1949)

- Troilo e Cressida by William Shakespeare (1949)

- Morte di un commesso viaggiatore of Arthur Miller (1951)

- Il seduttore of Diego Fabbri (1951)

- The crazy girl of Carlo Goldoni (1952)

- Tre sorelle of Anton Chejov (1952)

- Il tabacco fa male of Anton Chejov (1953)

- Medea Euripides (1953)

- Come le foglie by Giuseppe Giacosa (1954)

- Il Crogiuolo of Arthur Miller (1955)

- Zio Vania of Anton Chejov (1955)

- Contessina Giulia of August Strindberg (1957)

- L'impresario di Smirne of Carlo Goldoni (1957)

- One sguardo dal ponte of Arthur Miller (1958)

- Immagini e tempi di Eleonora Duse (1958)

- Veglia my house, angelo by Ketti Frings (da Thomas Wolfe) (1958)

- Deux sur la balançoire by William Gibson (1958)

- I ragazzi della signora Gibbons of Will Glickman and Joseph Stein (1958)

- Figli d'arte of Diego Fabbri (1959)

- L'Arialda by Giovanni Testori (1960)

- Dommage qu'elle soit une p... by John Ford (dramaturgo) (1961)

- Il tredicesimo albero of André Gide (1963)

- Après la chute of Arthur Miller (1965)

- Il giardino dei ciliegi of Anton Chejov (1965)

- Egmont by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1967)

- The Monaca di Monza by Giovanni Testori (1967)

- L'inserzione of Natalia Ginzburg (1969)

- Both tempo fa of Harold Pinter (1973)

Collaborations (prose drama)

- Carità mondana by Giannino Antona Traversi, staged (1936)

- Il dolce aloe by Jay Mallory, staged (1936)

- Il viaggio by Henry Bernstein, staged (1938)

- Vita col father by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse, supervision (1947)

- Festival of Age, Scarpelli, Dino Verde and Vergani, supervision, (1954)

Opera Director

- The Vestal of Gaspare Spontini (1954)

- The sonnambula by Vincenzo Bellini (1955)

- The traviata by Giuseppe Verdi (1955)

- Anna Bolena of Gaetano Donizetti (1957)

- Ifigenia in Tauride of Christoph Willibald Gluck(1957)

- Don Carlo by Giuseppe Verdi (1958)

- Macbeth by Giuseppe Verdi (1958)

- Il Duca d'Alba of Gaetano Donizetti (1959)

- Salome by Richard Strauss (1961)

- Il diavolo in giardino by Franco Mannino his libretto dello stesso Visconti, Filippo Sanjust and Enrico Medioli (1963)

- The traviata by Giuseppe Verdi (1963)

- Le nozze di Figaro by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1964)

- Il trovatore by Giuseppe Verdi (1964)

- Il trovatore by Giuseppe Verdi (1964), diverse

- Don Carlo by Giuseppe Verdi (1965)

- Falstaff by Giuseppe Verdi (1966)

- Der Rosenkavalier by Richard Strauss (1966)

- The traviata by Giuseppe Verdi (1967)

- Simon Boccanegra by Giuseppe Verdi (1969)

- Manon Lescaut by Giacomo Puccini (1973)

Ballets

- Mario e il Mago, choreographic action, (1956)

- Maratona di Dance, libretto (1957)

Awards and distinctions

- Oscar Awards

| Year | Category | Movie | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | Best argument and original script | The Fall of the Gods | Nominee |

- Cannes International Film Festival

| Year | Category | Movie | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | Palma de Oro | Il gattopardo | Winner |

- Venice International Film Festival

| Year | Category | Movie | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | International Prize | The earth trembles | Winner |

| 1960 | Special Jury Award | Rocco and his brothers | Winner |

| FIPRESCI Award | Winner | ||

| 1965 | Golden Lion | Sandra | Winner |

| New Cinema Award - Best Film | Winner |

Contenido relacionado

Santiago Aguilar Oliver

Prompter

Roos Tarpals