Louis Braille

Louis Braille (French pronunciation: /lwi bʁɑj/; Coupvray, Seine-et-Marne, France, January 4, 1809-Paris, France, January 6, 1852) was a French educator who designed a reading and writing system for people with visual disabilities. His system is known internationally as the Braille system and is used in writing, reading and musical notation.

Despite his premature disability, Louis Braille excelled in his studies and received a scholarship to the Institut National des Jeunes Aveugles. Still a student there and inspired by Charles Barbier's military cryptography, he crafted a tactile code specifically designed to make reading and writing easier for visually impaired students much more quickly and efficiently than existing methods in That moment.

Background

At the end of the 18th century France experienced profound political, social and cultural changes. During the French Revolution of 1789, a series of transformations began to take place that in turn were going to be decisive for people with disabilities. The old regime began to shake and crack in such a way that new changes occurred and new conditions appeared that were favorable for groups that until then had been marginalized from society, to have access to education and the basic rights of all citizens.. Until that moment, the only attention that had been given to people with visual disabilities were hospices created especially for them. Despite the fact that throughout history there were cases of people with this disability who stood out in the artistic, scientific or even political field, most were isolated cases of which little is known today.

Valentin Haüy, an erudite figure in the world of letters who held important positions in the Paris City Hall, in 1786 became very interested in trying to improve the situation of these people motivated by an experience that he himself described. Haüy observed the painful situation of a group of blind people who, sheltered in the Quinze-Vingt asylum (founded in 1269 by Louis IX), played music in the street to earn, between mockery and contempt, the occasional alms:

In September 1771, a café at the San Ovidio Fair presented an orchestra of ten blind, chosen among those who only have the sad and humiliating resource of begging their bread on the public track with the help of some musical instrument. How many times the listeners are rushing to offer a handful of alms to those disenfranchised, regretting not being able to do so by admiration, but by the desire to stop their terrible music. They had been grotesquely disguised; with robes and long punctuated hats. They had put on their nose ridiculous glassless cardboard glasses. And, placed before a pupitre with useless scores and lights, they executed a monotonous song: the singer, the violins and the bass all repeated the same melody [...] If — I said to myself — taken away by a noble enthusiasm, I will make this ridiculous farce a reality: I will read the blind, I will put into their hands books printed by themselves. They will betray the characters and read their own writing. Finally I will run harmonious concerts.

Haüy dedicated a large part of his life to the education of these people. The meeting in 1784 with the composer and pianist Maria Theresia von Paradis, blind since she was two years old and who had taught herself to read texts and music by touching pins stuck in cushions, greatly reinforced this great work of hers.

Haüy founded in 1786 the Institute for Blind Children, one of the first schools dedicated to the education of blind people. Likewise, he began to design a method of writing in relief that facilitated access to reading and writing through tactile perception. During the French Revolution, Haüy was removed as director of his Institute and it passed into the hands of the State and was called the Institute for Blind Workers until it finally became the headquarters of the National Institute for Blind Youth.

Biography

Early Years

Braille was born in Coupvray, a small town about 40 kilometers east of Paris. He and his three older siblings – Monique Catherine Josephine Braille (b. 1793), Louis-Simon Braille (b. 1795), and Marie Céline Braille (b. 1797) – lived with their mother, Monique, and their father, Simon-René, on three hectares of land and a few vineyards in the countryside. The Braille family was a humble family, traditionally dedicated to saddlery. Louis was the youngest son of a family made up of older parents and older brothers. All this determined a very special family framework, especially when dealing with a child who lost his sight at a very early age. It is possible, then, that his affable, warm, persistent, attentive and observant character was due in large part to that family framework that he was always so present in the early years of his childhood. Despite being a family with little cultural training and few resources, they showed great tenacity and skill so that Louis would develop just like the other children did at his age. It is notable that, given the circumstances, he did not become overprotective of his son because of his disability.

Simon-René, Louis's father, taught him to read by means of upholsterer's studs with which he formed the letters on a piece of wood or a piece of leather. Louis ran his fingers over those marks until he learned letters and whole words. In 1818 the Brailles sent his son to the town school with the same naturalness that they did with his other three children. Despite the fact that his learning was initially through oral transmission, the school teacher Antonie Bécheret was surprised to see that Louis could possess such a predisposed attitude towards learning. In his first years as a student, he obtained a scholarship to enter the National Institute for Blind Youth in Paris, which allowed him to start his studies, since his family did not have the resources to cover the expenses. From then on, he would begin a long path both as a student and as a teacher in that institute.

The visual impairment of young Louis Braille

In the year 1812, Louis was only three years old, and while he was playing in his father's workshop trying to imitate him, he took a tranchete that he used for his work and tried to cut a strap with such bad luck that a small accident of which there is no exact knowledge (a little piece of leather that could have jumped into his eye or the tip of the tool) injured his right eye. The inflammation ended up also damaging the left eye, causing irreversible blindness due to sympathetic ophthalmia. If this inflammation is not treated in time, the autoimmune reaction that is caused in the damaged eye ends up affecting the contralateral eye, which can cause irreversible blindness in both eyes. Given the context and also the economic situation, it was practically impossible that it would not end up affecting both eyes and that is why Louis was left with this disability at the age of five.

It must be borne in mind that when blindness occurs before the age of five or six, the child retains practically no clear visual image, not even the memory of the faces of his relatives or the place where he spent his childhood. In addition, the face itself loses part of its expressive mobility that arises as a natural effect of the spontaneous imitation of children at an early age. As a result of this, there are some descriptions that are still preserved in which some professors of the Institution de Ciegos de París describe him as not very expressive. Obviously, under this external appearance due to the precocity of his blindness, there was a person with great qualities that little by little would be discovered during his stay at the Institute.

The National Institute for Blind Youth

Initially, the Royal Institution for Blind Youth in Paris was made up of different buildings that were mostly old and not really equipped to receive students. In those buildings, a hundred young students with visual disabilities, in addition to service personnel, had to live and work in a house that had a chapel, a library, a printing press, classrooms for instrument classes, and a room for public exercises; in addition to the rooms of the students who lived there as boarding schools. The student dining room was a gallery with a staircase at each end and the main workshop (the loom) was a covered patio, which deprived the students of light. adjoining lower floors. The remaining workshops were separated by a simple balustrade and the rooms faced one another. There was also a bathroom that revealed terrible hygienic conditions, in addition to the fact that they used to bathe only once a month. In fact, the very reports of the doctors of that time illustrate a reality that seemed distant but true. In one of Pierre Henri's interventions he mentions one of the reports made by a doctor on May 14, 1838, and says: «Yesterday I went to visit the establishment for Blind Youth and I can assure you that there is not the slightest exaggeration in the description of that place [...] since, certainly, there is no description that can give you an idea of that narrow, infected and gloomy place; of those corridors divided in two to make true cubbyholes that are called workshops or classes there; of those innumerable tortuous and worm-eaten stairs that, far from being prepared for unfortunates who can only be guided by touch, seem like a challenge thrown at the blindness of those children [...].»

And other considerations from the students themselves who come to complete this testimony:

"Today the blind cannot form an exact idea of the many humiliations of this kind by which it was necessary to pass at that time when the visionaries in charge of our education, they still ignored to what extent our skill can come, so they demanded things far superior to which a blind man, however expert, can practice."

In summary, these are the conditions in which the young student and his classmates lived for more than 15 years. The school facility, however, was moved in 1843 to a new building in Paris and conditions improved, but possibly Louis Braille's state of health and the tuberculosis disease that accompanied him from an early age had already originated. in the old facilities.

Inheritance

Braille began to stand out first as a student and then as a teacher, also devising his reading and writing system known today as the braille system. Initially, the students of the Institute learned to read and write through Valentin Haüy's system, which consisted of preparing the letters in relief, despite the fact that in practice they were not very pleasant to touch. Louis, however, this system allowed him to read many of the printed books that were in the Institute's library, He also learned to write in pencil with the intention of being able to communicate with the psychics. To do this, he used molds that contained the empty letters along whose edges the pencil had to be slipped. He learned mathematics and geography in the same way. In the case of musical notation, for many years relief was dispensed with to incorporate musical teaching through oral transmission and memorization.

Since his admission, he demonstrated his ability to develop in different areas such as: grammar, rhetoric, history, geometry, algebra and above all music, both in theory and in practice (he learned to play the organ, cello and piano). In the institute, he taught more than one subject and made some history and arithmetic manuals for his students. In fact, he not only taught blind but also sighted children since at that time the institute admitted a certain number of sighted to those that were taught for free in exchange for a certain cooperation that was given to young blind people, such as helping them to read, write or guide them when walking.

Braille had a great reflective and methodical capacity, he was close to his students and managed to arouse their interest, understand them and advise them in the most difficult moments. Possibly this capacity for synthesis is derived from the complicated procedures of writing and printing, since, as he himself said, "we must try to express our thoughts with the fewest possible number of words".

Last years

From 1835 and due to the first symptoms of tuberculosis, he progressively withdrew from his teachings until he was solely in charge of music classes. In fact, the mentioned profession that appears in his will is that of & # 34; music teacher & # 34;. In the year 1840 he received classes from the best teachers: Mme. Van der Burch at the piano; Bénazet for the cello and Mangues for the organ. Braille was organist for many years at the church of Saint Nicholas des Champs in Paris. On the organ, says Cotalt, "her playing of him was exact, brilliant, and jaunty, and presented quite well the air of the whole person of him."

Louis Braille died at the age of 43 of tuberculosis, a disease that had accompanied him for a long time and that probably began due to the terrible hygienic conditions existing in the first Institute for Blind Youth. The funeral was held in the chapel of the National Institution and his body was transferred to his hometown to be buried in the small cemetery of Coupray, next to his father and his sister who had died years before. His coffin was deposited there on January 10, 1852. In 1952 his remains were transferred to the Panthéon in Paris. Only his hands remained buried in Coupray as a symbol to the tactile reading system he invented.

Braille system

In 1825 Louis Braille devised his system of raised dots that provided blind people with a valid and effective tool to read, write and facilitate access to education, culture and information.

The origins of the braille system and its diffusion

During the early years of the XIX century, there was great concern about finding a reading system that suited the needs of of people with visual disabilities. In fact, years before, the Italian priest Francesco Lana de Terzi, in his book Prodromo, introduced a new alphabet of his own invention for blind people, based on signs (hyphens) that could be recognized by touch.

Haüy had also tried to solve this problem by reproducing the letters in high relief, however this was a slow and complicated task. In April 1821 Braille was introduced to the Barbier system. Its creator, Charles Barbier, had always shown a special interest and great dedication to the study and experimentation of reading systems and one of his primary objectives was to improve the communications of the French army during those years. In this way he generated an encrypted code that he called "night writing" and that would be used so that officers in the campaign could write encrypted messages in the dark and also be able to decipher them with their fingers.

This writing presents a series of virtues that would later be taken and developed in the Louis Braille system. The first is the use of the dot as the key element to generate the tactile reading code (unlike the high relief used up to now) and the second is the fact that it does not use the common letter but rather generates other representations. Despite these advantages, the system also had certain drawbacks: Barbier's system does not represent the alphabet but groups of sounds from the French language. In addition, the base consisted of a high number of points that made it difficult to read quickly by touch. Barbier sonography was used at the institute for a few years until it was practically displaced by the Braille system, despite the fact that the latter was not initially accepted at the Institute.

Possibly during the year 1825, the most advanced students of the Institute who enthusiastically used the system devised by Barbier, began to reflect and discuss possible improvements to this new system. It is probable, therefore, that among all of them they tried to perfect sonography given the indisputable interest they had. This interest did not only consist of learning a system that would allow them to speed up their reading and writing skills, but also consisted of showing what they were capable of doing to a society with so many prejudices against the blind community. These students had to have their alphabet and possibly Braille was the young student who ended up finding the formula that allowed him to ingeniously perfect the system devised by Charles Barbier. Unlike Barbier, it was possibly the fact that Braille was blind that would endow him with greater "psychological intuition" and he tried to generate a sign made of dots that could form an image under the finger, synthetically converting tactile reading..

Particular features of the Braille system

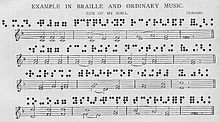

Before the age of 30, Louis had devised a system that perfectly matched the characteristics of tactile perception at the psychological, structural, and physiological levels. The braille sign, made up of a maximum of six dots, adapts perfectly to the fingertip and this means that the person can learn it in its entirety, transmitted as an image to the brain. This system consists of 63 characters formed from one to six dots and which, when printed in relief on paper, allow reading by touch. Likewise, the characters that make up the system, which Braille published in 1829 and 1837, are adapted to musical notation, thus facilitating their understanding.

Initially the system encountered strong opposition and it was even banned for many years in that Institute. Many teachers considered that this system, being different from the one used by the sighted, generated isolation and segregation for disabled students. This argument does not stop seeming on many occasions an excuse to justify that sighted people (especially Institute professors) did not use their time to learn a totally different code from conventional writing. In fact, it was blind people who defended and promoted the system, without a doubt the most suitable to decide on this issue.

There are many anecdotes that have survived those years in which the system was banned. For example, many students and some blind teachers at the Institute used it clandestinely by writing letters and copying texts that would later be shown to others, and so on. Thus, in 1844, thanks to the pressure exerted by these groups and coinciding with the inauguration of the Institute's new building on Boulevard des Invalides in Paris, the director claimed responsibility for the system by paying homage to its inventor. In 1853, a year after the death of Braille, the system was officially accepted by the Institutions and therefore its author was never officially recognized while he lived.

The Braille system, originating in France, used many symbols corresponding to the 64 combinations of the six dots to represent special accents corresponding to French. When used in other languages, the braille dot combinations change their meaning. For example, the full stop and capital sign change from Spanish to English. Likewise, Braille and his friend Pierre Foucault came to develop a typewriter to make the production of texts in Braille even easier: the ratigrapher.

Music and the musical notation system in Braille

Music had a special place in the life of Louis Braille. Throughout his life he dedicated himself to teaching music and was also a notable instrumentalist. Likewise, he devised a musical notation system in braille (Musical Braille Signography, currently known as musicography) for people with visual disabilities and also studied the possible forms of communication between musical writing in ink and in relief with the intention that they could be used and exchanged reciprocally between sighted and disabled people. We must keep in mind that during the decade of the XVIII century and even at the beginning of the XIX it was common to identify blindness with begging, something which led to the elimination of musical education from school programs for many years to avoid its kinship.

Tributes

In 1952, a century after his death, his remains were transferred to the French capital and buried in the Panthéon in Paris.

In 1999, an asteroid (9969) Braille was named in honor of Louis Braille.

Belgium and Italy each issued commemorative 2 euro coins in 2009 to celebrate the 200th anniversary of his birth.

Contenido relacionado

Joseph Nicephore Niepce

Francisco Varela

Jose Celestino Mutis

Pedro Duke

Chilean National Science Award