Lope de Vega

Félix Lope de Vega Carpio (Madrid, November 25, 1562 - Madrid, August 27, 1635) was one of the most important poets and playwrights of the Spanish Golden Age and Due to the length of his work, one of the most prolific authors of universal literature.

The so-called Phoenix of wits and Monster of Nature (by Miguel de Cervantes) renewed the formulas of Spanish theater at a time when theater was beginning to be a mass cultural phenomenon. The greatest exponent, along with Tirso de Molina and Calderón de la Barca, of Spanish Baroque theater, his works continue to be performed today and constitute one of the highest levels reached in Spanish literature and arts. He was also one of the great lyricists of the Spanish language and author of several novels and long narrative works in prose and verse.

Some 3,000 sonnets, three novels, four short novels, nine epics, three didactic poems and several hundred comedies are attributed to him (1800 according to Juan Pérez de Montalbán). A friend of Francisco de Quevedo and Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, at odds with Luis de Góngora and in a long rivalry with Cervantes, his life was as extreme as his work. He was the father of the also playwright Sor Marcela de San Félix.

Biography

Youth

Lope de Vega Carpio, a native of a noble family, although humble, with a plot of land, according to Lope himself, in Vega de Carriedo, today Vega de Villafufre, Cantabria, was the son of Félix or Felices de Vega Carpio, an embroiderer by profession, who died in 1578, and Francisca Fernández Flórez, who survived him by eleven years. There are no precise data on his mother. On the other hand, it is known that after a brief stay in Valladolid, his father moved to Madrid in 1561, perhaps attracted by the possibilities of the newly established capital of the Villa y Corte. However, Lope de Vega would later claim that his father came to Madrid for an affair from which his future mother would rescue him. Thus, the writer would be the fruit of reconciliation, and he would owe his existence to the same jealousy that he would analyze so much in his dramatic work.

He was baptized with the name of Lope, son of Feliz de Vega and his wife Francisca, in the parish of San Miguel de los Octoes on December 6, 1562. Lope had four siblings: Francisco, Juliana, Luisa and Juan. He spent part of his childhood in the house of his paternal great-uncle, Don Miguel de Carpio, Inquisitor of Seville.

A very precocious child, he was already reading Latin and Spanish at the age of five. At the same age he composes verses. In his Posthumous Fame..., his friend Juan Pérez de Montalbán describes those early days thus:

He went to school, surpassing others in the cholera of studying the first letters; and since he could not, by age, form the words, he repeated the lition more with the ademn than with the tongue. Five years old he read in romance and Latin; and it was so much his inclination to the verses, that while he could not write he shared his lunch with the other elders because they wrote to him what he dictated. He then passed to the studies of the Society, where in two years he became master of the Grammar and the Rhetoric, and before he turned twelve he had all the graces that allows the curious youth of the young, such as dancing, singing and bringing well the sword, etc.

He studied at the prestigious Imperial College of the Jesuits, then improperly called Theatinos. Always according to Lope himself, at twelve he wrote comedies ("I composed them at eleven and twelve years old / four acts and a four sheets / because each act contained a sheet»). It is possible that his first play was, as Lope himself would affirm in the dedication of the work to his son Lope, El verdadero amante, although the text we know today of this play probably underwent modifications after the date of first writing. This tremendous facility for writing he attributed to a natural gift. And so, through the mouth of Belardo, when they ask him for some sonnets for the king in The animal of Hungary and they ask him how long it will take, he writes:

In an hour. - An hour? - And less, and exhaust. / —Callad, it cannot be, / that many I hear say / that those who make sudan, / grow, groan and roam / as who wants to give birth... / —Fal them the natural / that gives the sky to whom he wants.

His great talent led him to the school of the poet and musician Vicente Espinel, in Madrid, whom he always quoted with veneration (he dedicated his comedy El caballero de Illescas, c.1602). Thus the sonnet: This pen, famous teacher / that you put in my hands, when / the first characters were signing / I was, fearful and inexperienced... While studying around 1573 at the Theatine College, he translated into Spanish verse Claudiano's poem De raptu Proserpinae, which he dedicated to Cardinal Colonna. He continues his training with the Jesuits (1574):

The letters of litions served me as drafters for my thoughts, and often wrote them in Latin or Spanish verses. I began to gather books of all letters and languages, that after the beginnings of the Greek and large exercise of the Latin, I knew well the Tuscan, and of the French I had news... (The Dorotea, IV).

Later, he studied four years (1577-1581) at the Colegio de los Manriques of the University of Alcalá, but did not obtain a degree. Perhaps his disorderly behavior and womanizing (already in 1580 the student Lope was cohabiting with María de Aragón, the Marfisa of his verses, from whom he had his first daughter, Manuela the following year) of a fatherless makes him unfit for the priesthood. Many of the characters in his early comedies are true libertines. He himself, through the mouth of Belardo, paints himself like this:

If I flatter the beautiful/sold as the friend, / and as I say it / I am feeling something else. / I ask you to love me; / and, if I come to reach you, / I already have full place / that it is very foolish and very fierce...

His high protectors stop paying for his studies. Thus, Lope does not get a bachelor's degree and to earn a living he has to work as a secretary to aristocrats and great men, or writing comedies and circumstantial pieces. In 1583 he enlisted in the navy and fought in the battle of Terceira Island under the command of his future friend Álvaro de Bazán, I.ermarquis of Santa Cruz. Time later he would dedicate a comedy to the son of the marquis.

Banishment

He studied at that time (perhaps 1586) liberal arts with the teacher Juan de Córdoba and mathematics and astrology at the Royal Academy with Juan Bautista Labaña, Felipe II's senior cosmographer, and served as secretary to Pedro Esteban Dávila y Enríquez, marquis de las Navas; but from all these occupations the continuous love affairs distracted him. Elena Osorio, whom he met in 1583, was her first great love, the "Filis" of her verses, then separated from her husband, the actor Cristóbal Calderón; Lope was with her for four years and repaid her favors with comedies for the company of the father of her beloved, the theater manager or author Jerónimo Velázquez. In 1587 Elena accepted, for convenience, to establish a relationship with the noble Francisco Perrenot Granvela, nephew of the powerful cardinal Granvela. A spiteful Lope de Vega then circulated some of her libels against her and her family, including one in macaronic Latin, In doctorum Damianum Velazquez Satira Prima , which has not been preserved:

- A lady sells to whoever wants her.

- Almond's in. You want to buy it?

- His father is the one who sells it, even if he shuts it,

- His mother served her as a pregoner...

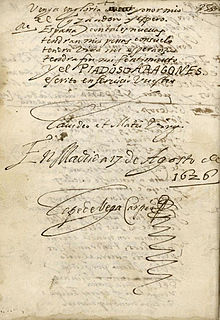

He denounced the situation in his comedy Belardo furioso and in a series of sonnets and pastoral and Moorish romances. He had a judicial process and ended up in jail for defaming Elena. He reoffended and a second judicial process was more emphatic: he was banished from the Court for eight years and two from the kingdom of Castile, with the threat of death if he disobeyed the sentence. Lope de Vega took revenge by selling his comedies to the businessman Porres and years later he would recall his love affair with Elena Osorio in his dialogue novel ("prose action" he called it) La Dorotea . However, by then he had already fallen in love with Isabel de Alderete y Urbina, daughter of King Diego de Urbina's painter, whom he married on May 10, 1588 after kidnapping her with her consent. In her verses he called her with the anagram "Belisa".

On May 29 of the same year, he tried to resume his military career by marching to Lisbon with his friend Claudio Conde, enlisting in the Great Navy, on the galleon San Juan; his intention was, at least, for that reason to reduce his sentence, according to recent documents have revealed.At that time he wrote an epic poem in real octaves in the style of Ludovico Ariosto, The beauty of Angélica , that went unnoticed. It is probable that his enlistment in the navy mobilized for the assault on England was the condition imposed by the relatives of Isabel de Urbina, eager to lose sight of such an unpresentable son-in-law, to forgive him for kidnapping the young woman. his trip to England when, through Belardo, he complained about not having yet gone to see the monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, despite having traveled so far:

I was born / in Madrid, and confident / to be so close, I have been / without seeing it until agora, and I was / 2 thousand leagues once / only to see England...

The reason for this game however seems quite complex. In his Arcadia he included in this regard some verses that declared an image of Spain that he never repeated again, however: a beloved country but essentially envious and ungrateful:

Oh, sweet and face Spain, / stepmother of your true children / and, with strange piety, / pious mother and host of strangers! / Envidia in you kills me, / that every homeland is usually ungrateful. / But, because it is my glory / revenge my enemies with my absence, / I will have for more victory / equal with your envy my patience / not to suffer the fury / of which you do not see and the other insult... / I give birth to be an example / of vain hopes and favors, / because I already contemplate / out of their envy and fears, / where my life ends / poor, envied, sad and persecuted (BAEXXXVIII, 65 (a)

In December 1588 he returned on the ship San Juan after the defeat of the Great Armada and headed for Valencia, once again with his friend and almost brother Claudio Conde, after breaking his sentence passing by Toledo. He lived in Valencia with Isabel de Urbina and there he continued to perfect his dramatic formula, attending the performances of a series of geniuses who would later form the so-called Academy of the nocturnes, such as the canon Francisco Agustín Tárrega, the secretary of the Duke of Gandía Gaspar de Aguilar, Guillén de Castro, Carlos Boil and Ricardo de Turia. He learned to disobey the unity of action by telling two stories instead of one in the same work, the so-called imbroglio or Italian imbroglio. Claudio Conde ended up in the Torres de Serranos prison, but Lope got him out of there.

After completing two years of exile from the kingdom, Lope de Vega moved to Toledo in 1590 Isabel de Urbina, the "Belisa" of some of her poems and the heroine of Las bizarrías de Belisa was a minor when she married Lope. The family of the young woman, of high social position, rejected this marriage, motivated in large part by the sentence to exile against Lope because of the insults against the comedian Jerónimo Velázquez and his family. The lovers organized the kidnapping of the bride and, before the fait accompli, the Urbina ended up accepting a marriage by proxy because of their exile. After two years in Valencia and eight years from fully serving the sentence, Lope decided to settle on Calle de la Sierpe in Toledo, so close to Madrid that he could continue to be in contact with the center of the monarchy without violating the distance ("five leagues away"). of the court”) established in the sentence”. And there he served Francisco de Ribera Barroso, later the second Marquis of Malpica and, some time later, the fifth Duke of Alba, Antonio Álvarez de Toledo y Beaumont. For this he joined the ducal court of Alba de Tormes as a gentleman of the chamber, where he lived between 1592 and 1595. In this place he read the theater of Juan del Encina, from which he took the character of the graceful or graceful figure, further perfecting its dramatic formula. Near Alba de Tormes there was also the Castillo del Carpio, which helped him to fantasize about a possible chivalrous origin of his last name, related to that of the hero Bernardo del Carpio, to whom he dedicated three comedies. In the fall of 1594 Isabel de Urbina died of labor or puerperium. At that time she wrote her pastoral novel La Arcadia , where she introduced numerous poems and an engraving that represented the shield of Bernardo del Carpio: nineteen towers. This boast caused the ridicule of Luis de Góngora, who dedicated a sonnet to him:

For my life, Lopillo, that you erase me / the nineteen towers of the shield / because, though all are of wind, I doubt / that you have wind for so many towers...

This coat of arms was considered to belong to the lineage of Bernardo del Carpio because it could be seen in a relief of the tomb of Pedro Bernardo del Carpio (1135), considered a descendant of the legendary hero, in the old church of San Martín in Salamanca.

Vuelta a Castilla

In December 1595 he completed eight years of exile from the Court and returned to Madrid. The following year, right there, he was prosecuted for cohabiting with the widowed actress Antonia Trillo. In 1598 he married Juana de Guardo, daughter of a wealthy court meat supplier, which led to the ridicule of various mills (Luis de Góngora, for example), since she was apparently a vulgar woman and everyone thought that Lope she had married for money, since love was not precisely what she lacked. He settled in Toledo for the second time, from August 1604 to 1610, with his wife and his lover Micaela de Luján and children. He lives with his legitimate wife in a house "in the alley of the San Justo neighborhood" (today Juan Guas street). The exact property of the house inhabited by Lope and Juana Guardo on Juan Guas street is unknown, although the document de rent informs that it belonged to his friend, the writer Gaspar de Vargas. Lope noted that it was so high "that it has made me think that from here with less work you can reach heaven", something that agrees with the height of some of these houses that allow a certain aerial sensation from their windows. In September 1610, the couple left this home and moved to Madrid, where three years earlier Lope had already rented a house with Micaela Luján. Jokingly, Lope blames the sacristan of the Church of Santos Justo y Pastor (“San Yuste”) for his departure, because, apparently, the ringing of bells so close to his home bothered him. This is indicated in a letter addressed to his friend from Toledo, the Doctor of Law Gregorio de Ángulo:

“God keep the Peralera my years,/that if there were no sacristantes in San Yute,/Madrid would never see me in its corner”

La “Peralera” (currently “Peraleda”) is a farm adjacent to the Palacio de Buenavista (Toledo), separated by a section of the Tagus River, which surely constituted a scene of pleasant walks among the members of the Literary Academy of Buenavista, of which the writer was a part during his stays in Toledo. Simultaneously, he rents a house from his lover in the nearby San Lorenzo neighborhood of the Imperial City.Lope had up to five children with the actress from La Mancha Micaela de Luján (Angelilla, Mariana, Félix, Marcela and Lope-Félix).. The "Celia" or "Camila Lucinda" of her verses was a beautiful, but uneducated and married woman, with whom he maintained relations until 1608, when the literary and biographical trace of her was lost. She was unique among the older lovers of the Phoenix whose separation left no mark on his work. In 1606 his wife Juana Guardo gave birth to Carlos Félix, a much loved son of Lope.

In Toledo he had numerous friends, such as the poet Baltasar Elisio de Medinilla, to whom he dedicated his comedy Santiago el Verde, from around 1615 (Lope wept in verse for his accidental murder in 1620). He returned to work as personal secretary of Pedro Fernández de Castro y Andrade, at that time IV Marquis of Sarria and future VII Count of Lemos, to whom he wrote in a letter: «I, who so often at his feet, like a faithful dog, I've slept".

For many years Lope was divided between the two households and an indeterminate number of lovers, many of them actresses, among others Jerónima de Burgos, as attested by the legal process that was opened against him for being in cohabitation in 1596 with Antonia Trillo; the name of another lover, María de Aragón, is also known. To sustain this way of life and support so many relationships and legitimate and illegitimate children, Lope de Vega displayed an unusual firmness of will and had to work very hard, lavishing a torrential work consisting, above all, of lyrical poetry and comedies, printed you are many times without his permission, distorted and without correction.

At the age of thirty-eight he was finally able to correct and edit part of his work without the errors of others. As the first professional writer of Spanish literature, he sued to obtain copyrights over those who printed his comedies without his permission. He got, at least, the right to correct his own work.

In 1602 he made a trip to Seville, where his uncle don Miguel del Carpio had lived, brother of his mother and feared inquisitor in Seville, with whom he was educated in his childhood, when he was eight or nine years old at most. He met the classicist poet Juan de Arguijo, a nobleman and musician who held the position of twenty-four and was his host and patron, including him in the gathering that he met in his house, and from there he visited Granada on one or two occasions.. During this last trip he stopped in Antequera, where he was treated and feted by the poet Luis Martín de la Plaza, who composed two sonnets for the occasion. It is also proven that he met the poet Antonio Ortiz Melgarejo and the great and already famous novelist Mateo Alemán in Seville. In Seville Lope completed La hermosura de Angélica, printed in Madrid in 1602 in the same volume in the that the three parts of his celebrated Rhymes were included, openly Mannerist, which includes among his two hundred sonnets a group that forms a Petrarchan songbook dedicated to Lucinda; they are also dedicated to Arguijo himself.

In 1605 he entered the service of Luis Fernández de Córdoba y de Aragón, sixth Duke of Sessa. This relationship would torment him later, when he took holy orders and the nobleman continued to use him as a secretary and pimp, so that even his confessor would deny him absolution. This is verified by the abundant correspondence that he exchanged with the Duke, which has been published modernly.

In 1609 he read and published his New Art of Making Comedies, a capital theoretical work, contrary to Neo-Aristotelian precepts, and entered the Brotherhood of Slaves of the Blessed Sacrament in the oratory of Caballero de Gracia, to which almost all the relevant writers in Madrid belonged. Among them were Francisco de Quevedo, who was a personal friend of Lope's, and Miguel de Cervantes. He had strained relations with the latter because of the antilopesque allusions in the first part of Don Quixote (1605). The following year, he joined the oratory on Calle del Olivar.

Priesthood

The time that sponsored Lope de Vega's priestly ordination was one of a deep existential crisis, perhaps driven by the death of close relatives. His Sacred Rhymes and the numerous devotional works that he began to compose respond to this inspiration, as well as the meditative and philosophical tone that appears in his last verses. The writer was the victim of an assassination attempt from which he barely escaped on the night of December 19, 1611. Juana de Guardo suffered frequent illnesses and in 1612 Carlos Félix died of fever. On August 13 of the following year, Juana de Guardo died, giving birth to Feliciana. So many misfortunes affected Lope emotionally, and on May 24, 1614, he finally decided to be ordained a priest Lope was ordained a priest in his diocese of Toledo and as a first measure, the cardinal's assistant, titular bishop of Troy, ordered him to shave his head. the mustache and the goatee, since their use goes against the synodal laws. His response is famous: "From Troy had to come what would appease my fires." While awaiting his ordination, he stays at the home of his ex-lover, Jerónima de Burgos, and since he continues to pimp the love correspondence of his protector, the Duke of Sessa, his confessor denies him absolution after being ordained a priest, but Cardinal Bernardo de Sandoval y Rojas, much more condescending, appoints him as a member of the court that was conducting the process of beatification of Teresa de Jesús, and two years later again appoints him prosecutor of the Apostolic Chamber of the Archbishopric of Toledo, based on "his gifts of wisdom, the rectitude of his behavior and the good reputation in both divine and human letters. On the contrary, the successor of Sandoval and Rojas, the Cardinal Infante Don Fernando of Austria (son of Felipe III), will not take long to dismiss him because of his conduct weaknesses. In his correspondence, Lope shows the doubts he harbors at this time about the orientation that he has to give to his life, reaching disturbing conclusions: «I was born in two extremes, which are to love and hate; I have never had the means... I am lost, if in my life I was, for the soul and body of a woman, and God knows with what feeling of mine, because I do not know how this is going to be or last, nor live without enjoying it...» (1616). However, the priesthood opened the faucet of ecclesiastical benefits for him: through the Duke of Sessa he obtained a "lender" in the diocese of Córdoba and in 1615 he requested a chaplaincy that his former protector Jerónimo Manrique instituted in Ávila. In October of that same year he accompanied his lord in the retinue that went to Irún with the Infanta Ana of Austria and gave an honor escort to Madrid to Isabel de Borbón, future wife of Felipe IV; but the duke asked Lope in correspondence to continue serving as a pimp, and that broke the conscience of the now priest. However, some women involved in Lope's dealings did not stop scandalizing the Toledo neighborhood.

The literary expression of this crisis and its regrets are the Sacred Rhymes, published in 1614; there he says: «If the body wants to be earth on earth / the soul wants to be heaven in heaven», irredeemable dualism that constitutes his entire essence. The Sacred Rhymes are a book that is both introspective in sonnets (he uses the technique of spiritual exercises that he learned in his studies with the Jesuits) and devoted to poems dedicated to various saints or inspired by the sacred iconography, then in full swing thanks to the recommendations issued by the Council of Trent. He was then surprised by the aesthetic revolution caused by the Soledades by Luis de Góngora and, although the aesthetic tension of his verse increased and bi-membering began to appear at the end of his stanzas, he distanced himself from extreme culteranismo and continued cultivating his characteristic mixture of conceptism, cultured Castilian traditionalism and Italian elegance. Plus, he taunted the new aesthetic and made fun of it when he got the chance. Góngora reacted with satires to this hostility, which the Phoenix always raised in an indirect way, taking advantage of any corner of his comedies to attack, more than Góngora himself, his disciples, an intelligent way of confronting the new aesthetics and that has to do with his famous conception of satire: "Pique without hate, that if anything slanders / neither expect glory nor claim fame." In any case, he ambiguously tried to ingratiate himself with the Cordovan ingenuity by dedicating his comedy Secret Love to Jealousy (1614), with a very significant title. On the other hand, he had to fight with the contempt of the Aristotelian preceptors who condemned his dramatic formula as contrary to the three units of action, place and time: the poets Cristóbal de Mesa and Cristóbal Suárez de Figueroa and, above all, Pedro Torres Rámila author of a Spongia (1617), a libel intended to denigrate not only Lope's theater, but also all his narrative, epic and lyrical work. Lope's humanist friends responded furiously against this pamphlet, headed by Francisco López de Aguilar, who wrote an Expostulatio Spongiae a Petro Hurriano Ramila nuper evulgatae in June 1618. Pro Lupo a Vega Carpio, Poetarum Hispaniae Principe. The work contained praise for Lope from none other than Tomás Tamayo de Vargas, Vicente Mariner, Luis Tribaldos de Toledo, Pedro de Padilla, Juan Luis de la Cerda, Hortensio Félix Paravicino, Bartolomé Jiménez Patón, Francisco de Quevedo, the Count of Salinas, and Vicente Espinel, among others less known. Encouraged by this support, Lope, although besieged by criticism from cultists and Aristotelians, continues with his epic attempts. After Góngora's Polifemo, he essays the extensive mythological fable with four poems: La Filomena (1621; where he attacks Torres Rámila), La Andrómeda (1621), La Circe (1624) and The White Rose (1624; coat of arms of the count-duke's daughter, whose complicated mythical origin it exposes). He returns to the historical epic with The Tragic Crown (1627, in 600 octaves about the life and death of Mary Stuart).

Last years

In the last years of his life, Lope de Vega fell in love with a twenty-five-year-old girl, Marta de Nevares, married at thirteen, in what can be considered "sacrilege" given his status as a priest; She was a very beautiful woman, with curly hair and green eyes, a skilled singer and dancer, as Lope declares in the poems he composed for her, calling her "Amarilis" or "Marcia Leonarda" since her husband died in 1619, as in the Novels that he destined for her. At this time in his life, he especially cultivated comic and philosophical poetry, doubling himself in the burlesque heteronymous poet Tomé de Burguillos and serenely meditating on his old age and crazy youth in romances such as the famous "barquillas".

In 1627 he entered the Order of Malta, and to date it has been discussed whether he should have provided proof of his nobility through his father's branch and was exempted from the other three mandatory quarters, or whether it was exclusively at the behest of the pope that the Grand Master received him in the Order. Be that as it may, this membership was an enormous honor for Lope, who in the most widespread portrait of him wears the habit of San Juan. Lope's interest in the orders of chivalry in general, and in that of Malta in particular, led him to write between 1596 and 1603 the play El valor de Malta, set in the maritime fights that the Order held throughout the Mediterranean with the Turks. But between March and April 1628 he fell so seriously ill that he was at death's door, as he writes to the Duke of Sessa:

Your Excellency, thank God, Lope de Vega, who had not had him until today: so he doubted my life. I cried on this evil black man, that black must be, for Your Excellency prescribes me black, more than twenty days with great work and sorrow, so much that I understood that I had become Don Juan de Alarcón; and at last I fell into bed, today eighteen days ago, of such a painful swelling, that I lit in terrible socks and caused so many evils that I was already wept by the domestic and strange Musas. May God be praised, His Most Holy Mother and Saint Isidro, who am in the port of clarity, that in April, and [with] not a few years, much to fear.

Lope was already sixty-six years old. The pang against Juan Ruiz de Alarcón can be explained by the gossip: in the comedy of the severe and moralizing Mexican ingenuity Los pechos privilegiados a mischievous allusion to the marital union of the donjuán priest and the girl had slipped:

- Blame an old velvet/so green that, at the same time / that is bound by tins, / walks making muffins.

Among the barely hidden scandal of the almost twenty years of his life that he spent with Marta de Nevares Santoyo and despite the honors he received from the king and the pope, Lope's last years were unhappy. The Count-Duke of Olivares ignored him for having served the Duke of Lerma and for being Sessa's secretary, disgraced and banished from the Court. In addition, Lope's private calaveras caused the Palace to dismiss his claims for positions, honors and perks, since Olivares wanted to moralize customs after the rampant corruption of the reign of Felipe III. In his Eclogue to Claudio (1632), addressed to his old friend and companion of youth adventures Claudio Conde, his bitter disappointment appears for having tried to reach the permanent position of chaplain to the Duke of Sessa or that of chronicler of Felipe IV and considers himself back from everything. In addition, he had suffered when Marta became blind in 1626 and died insane in that same year of 1632, as he recounts in the memory he dedicates to her in the eighth reales of the eclogue Amarilis, which would be published in 1633. Also in 1632 he published La Dorotea, a meditation on his youthful love affairs. And he evokes the death of Marta in this sonnet from the Rimas humanas y divinas by Tomé de Burguillos (1634) entitled «That time and death do not forget true love»:

Solved in dust already, but always beautiful, / without letting me live, lives serene / that light, which was my glory and sorrow, / and makes me war, when in peace I rest. / So alive is the jasmine, the pure rose, / that, softly burning in blue, / I embrace the soul of full memories: / ash of his loving phoenix. / Oh, cruel memory of my anger!, / what honor can give you my feeling, / in dust turned your spoils? / Allow me to call only a moment: / that no longer have tears my eyes, / no concepts of love my thought.

Las Rimas humanas y divinas (1634), the last of his poems, indicates that Lope de Vega was already writing for himself, to entertain himself, escape and distance himself through parody and humor, How important are they in this collection? Well, there were even more misfortunes: Lope Félix, his son with Micaela de Luján and who also had a poetic vocation, drowned fishing for pearls in 1634 on Margarita Island, off the coast of Venezuela. His beloved daughter Antonia Clara was kidnapped by a hidalgo, her boyfriend, named Tenorio to top it off. Feliciana, his only legitimate daughter at that time, had had two children: one became a nun and the other, Captain Luis Antonio de Usategui y Vega, died in Milan in the service of the king. Only one of his natural daughters, the nun Marcela, survived him.

Lope de Vega died on August 27, 1635. His remains were deposited in the church of San Sebastián, on Calle de Atocha. In the middle of the same century XVII went to the common grave. Two hundred authors wrote praises to him that were published in Madrid and Venice. During his lifetime, his works gained a mythical reputation. "Es de Lope" was a phrase frequently used to indicate that something was excellent, which did not always help to attribute his comedies correctly. In this regard, his disciple Juan Pérez de Montalbán recounts in his Fama posthumous to the life and death of Doctor Frey Lope de Vega Carpio (Madrid, 1636), a print composed to exalt the memory of the Phoenix, that a man he saw a magnificent burial go by saying that "it was Lope's", to which Montalbán added that "he was right twice". Cervantes, despite his antipathy for Lope, called him "the monster of nature" because of his literary fecundity.

Marriages and offspring

During his life, Lope de Vega was a man fond of love affairs, which more than once brought him difficulties. In total he had fifteen documented children between legitimate and illegitimate:

- With Mary of Aragon (called Marfisa in the works of Lope), daughter of a flamenco baker, called Jácome de Antwerp, installed in Madrid:

- ManuelaApparently the firstborn of all her prole. Baptized on 2 January 1581, he died on 11 August 1585.

- After the end of the relationship, Marfisa married a flamenco in 1592 and died on September 6, 1608.

- With Isabel Ampuero de Alderete Díaz de Rojas y Urbina (known as Isabel de Alderete being single, and as Isabel de Urbina when she married), her first wife, with whom she married by powers on May 10, 1588, after having "raptured" her from the paternal house (although in fact she agreed to go voluntarily):

- Antonia, probably born in 1589, died in 1594, apparently shortly before his mother.

- Theodoraborn in November 1594, died in childhood between 1595 and 1596.

- Isabel de Urbina died in the birth of her second daughter, in November 1594.

- With Juana de Guardo, his second wife since April 25, 1598. Daughter of Antonio de Guardo, rich meat and fish supplier from Madrid, is believed to be a marriage of convenience:

- Jacinta, baptized in Madrid on 26 July 1599, possibly deceased in childhood because there is no more news of it.

- In a letter written to a friend dated August 14, 1604, Lope announced that his wife is about to give birth. In his 1627 testament, Lope named a daughter, Juanaalready dead. It is likely, given the name and dates, that this daughter is the creature born of Lope and his wife in August 1604.

- Carlos Félix, baptized on March 28, 1606, so it is believed that the previous year was born in 1605. Predilect son of his father died on June 1, 1612, after a disease of several months. The devastated Lope gives you a choice published in the Rimas Sacras.

- Felicianaborn on 4 August 1613. The only legitimate offspring to survive childhood, married Luis de Usátegui, "official of the secretariat of the Royal Indian Council of the Province of Pirú", on 18 December 1633. Lope promises to give her daughter with clothes and money worth 5000 ducats, the inheritance of her maternal grandparents.

- Juana de Guardo died nine days after giving birth on August 13, 1613, due to overpart. Lope didn't get married again. In early March 1614 he received minor orders in Madrid. On March 12 he went to Toledo (located at the house of the actress Jerónima de Burgos, with whom he had an affair), where he received the degree of clergy of epistle and then the Gospel. On May 25, in Madrid, he received the last degree of his priestly ordination. On May 29, he said his first mass at the Carmen Descalzo church in Madrid.

- With the actress Micaela de Luján, married to the actor Diego Díaz, who was absent to Peru, where she died in 1603. Mother of nine children, five of them are at least Lope, with whom she maintained a relationship of about fifteen years (possibly begun after her second marriage, about 1599), despite other fleeting loves:

- Angela.

- Mariana.

- Felixbaptized on October 19, 1603.

- Marcela, baptized on May 8, 1605. On February 2, 1621 it is consecrated in the convent of Trinitarias Descalzas, with the name of Sister Marcela de San Felix. Lope describes the consecration in the Epistle to Don Francisco de Herrera Maldonado.

- Lope Felixborn on 28 January 1607. Boy of a discola nature, he was locked up by his father, due to his bad behavior, in the asylum of Our Lady of the Disarmed, in 1617. With literary inclinations like his father, in the end he became military, dying in 1634 on a shipwreck on the coast of Venezuela, where he had gone on an expedition to fish pearls. Lope dedicated him a piscatory egloga.

- With Marta de Nevares, Marcia Leonarda of novels, and Amarilis of the poems and letters of Lope), born about 1591 and married on August 8, 1604 (against his will) with Roque Hernández de Ayala, a merchant, of which soon separated. Amateur of poetry, she wrote verses, sang, tañía and danced, was of good conversation and prose, and even had talent as an actress (represented a comedy of Lope in her house). His relations, begun around September 1616, had as fruit a daughter:

- Antonia Clara (Clarilis), born on 12 August 1617. The minor of all his descendants and the joy of his old age, escaped from the father's home on August 17, 1634 with Don Cristóbal Tenorio, a knight of the Order of Santiago, a protector of the Count-duke of Olivares and help of the House of His Majesty. Lope never recovered from this blow.

- Marta de Nevares was blind in 1622, and then lost his reason. He died in the care of Lope at his house on April 7, 1632. I was 41. This was the last significant relationship in the life of Lope de Vega.

In addition to these offspring, Lope de Vega procreated two other children from fleeting relationships:

- Fernando Pellicer, Fray VicenteThere's a valencian.

- Fray Luis of the Mother of God, of an unknown mother.

Narrative work

The Arcadia

The author did not dare to publish an unstructured collection of poems, nor did he want to give up presenting his verses in society under his name. The expedient chosen was —and it is the usual formula at the time— to frame them in a pastoral novel: Arcadia, written in imitation of the homonymous work by Jacopo Sannazaro and his Spanish followers. The lopesca novel saw the light of day in Madrid in 1598. It had considerable success. It was the most reprinted Phoenix work in the 17th century: Edwin S. Morby records twenty editions between 1598 and 1675, of they sixteen in life of the author. Osuna recalled "there are about 6,000 [verses] that the novel contains, more than prose lines in the edition that we handle." Indeed, today the reader finds it difficult to imagine that a novel, no matter how poetic it may be, can contain more than 160 poems, some of them brief, but of considerable length. It does not seem that such a number of verses serve as an ornament to the prose. Rather, they reveal to us that the story becomes an excuse to offer the public an extensive previous poetic production, to which he probably added numerous lyrical compositions written ad hoc .

The pilgrim in his homeland

This new novel in which Lope tries out the Byzantine or adventure novel —with the peculiarity that all of them take place within Spain— saw the light of day in Seville at the beginning of 1604. It was an immediate success (there are two Madrid prints and another two from Barcelona from 1604 and 1605, another from Brussels from 1608 and a new revised edition from Madrid, 1618). The pilgrim in his homeland does not present the poetic richness of Arcadia . Not because the number of interspersed verses is less, but because many of them are dramatic: four sacramental plays, with their praises, prologues, songs. Among the thirty or so poems that he introduced into the Byzantine narrative, there is not much to note.

Shepherds of Bethlehem

Shepherds of Bethlehem. Divine Prose and Verse appeared in Madrid in 1612. The work enjoyed notable success. In the same year, new publications were published in Lérida and Pamplona. Six new editions would come out during the poet's lifetime. We are before a declared contrafactum that pours into sacred matter that mixture of prose and love verses of the Arcadia of 1598. The canvas of the pastoral novel is used here to narrate some episodes evangelicals related to the Nativity of the Lord. Like Arcadia, it contains an extensive poetic anthology. A total of 167 poems of the most varied metric forms have been catalogued.

Dorothea

Like other poetic cycles, this one on old age was opened by Lope with a prose text, in this case in dialogue, in which he inserted a varied poetic anthology. La Dorotea appeared in 1632. It is probably no coincidence that the first poem to be heard in the action in prose is "I'm going to my solitudes" and that it appears expressly attributed to Lope. The penultimate of his elegies, and the most celebrated, "Poor little boat of mine", has the fragile little boat as its interlocutor.

Lope calls this work «action in prose», and its most obvious model is the celestinesque genre. It evokes the story of her jealous love for Elena Osorio from the height of her adulthood. The style is simple and natural, but sometimes, as in Lope's other works, particularly the prologues, he gathers a stony, cheap erudition taken fundamentally from the encyclopedic repertoires of the time, among which he had a particular fondness for Dictionarium historicum, geographicum, poeticum by Carolus Stephanus (1596) and the inevitable Officina and Cornucopia by Jean Tixier, better known as Ravisio Textor.

Lyrical work

In his novel La Arcadia (1598) and in other places Lope de Vega reiterates that he agrees with Pierre Grégoire's Syntaxeon in that the lyric is a conjunction of initial natural inspiration and later rhetorical work:

It consists of its precepts poetry / being art of ingenious preeminence, / although nature its harmony / first infuses with greater violence. / Help the Art, and together for porphy / come to such extreme of excellence / it seems divine and rare furor / and its strength clear instrument

Later on, in the Silva V.ª of his Laurel de Apolo, written in measured Gongorism, he writes that "poetry is / an art that, consisting of precepts / dresses of figures and concepts". Regarding the poet's relationship with the musicians, Lope composed many songs, mainly letrillas and tonos for the five-string vihuela; he worked first in his youth with the Sevillian composer Juan Palomares, and when he died, with Juan Blas de Castro, both of whom he always remembered with gratitude in many passages of his works; for example, of the latter he wrote in El acero de Madrid (1608):

Glassy streams, / sound noise and meek / that seems to run / tones of Juan Blas singing, / because already running fast / and already in the guides slowly, / it seems that you enter in leaks / and that you are typical and low.

Romances

Together with his eternal rival, Luis de Góngora from Córdoba, Lope led a precocious poetic generation that became known in the decade between 1580 and 1590; They are the so-called «romance poets» who return to the eight syllable when the fever of the hendecasyllable and the Italian stanzas introduced by Garcilaso and Boscán in the first half of the century has passed. XVI; they do not disdain the Italian school and continue to cultivate its forms, but they no longer disdain the previous octosyllabic and popular tradition of the XV century and the they also assume writing what will later be known as New Ballads. From the early age of eighteen or twenty these poets began to be known and celebrated for their romances and —it is obvious— they had no great interest in controlling or demanding anything from the printers. They are, in general, young poets (Lope, Góngora, Cervantes, Pedro Liñán de Riaza), less than thirty years old and often they did not bother to claim their authorship, at least directly. Modern criticism has taken care to elucidate the authorship of this or that ballad, but has not made the necessary effort to seriously try to establish the corpus ballads of the different poets. Lope's has remained in vague approximations. Much has been said about the meaning and scope of this romancero from the generation of 1580, in which Lope imposes guidelines recreated by many others. The leading role of our poet was recognized from the outset. The new romancero was a literary formula that quickly caught on with social sensibility and young poets proposed to their readers and listeners a happy hybrid of conventional fantasy and coded references to love affairs, favors and disdains, likes and dislikes of the activity. erotica. But sentimental exhibitionism is not presented in them naked. It appears, for greater charm, veiled by the heroic fantasy of Moorish romances or by pastoral melancholy. The age-old tradition of frontier romances, composed for the most part in the XV century in line with the historical events to which they allude, revived at the end of the XVI century in this fashion genre.

Los moriscos were the first fashionable romances composed by the generation of 1580 [vid. "Saddle me the Dapple donkey"; "Look, Zaide, I'm warning you"]. The fashion for the Moorish ballads was replaced by the pastoral, although there was a time when both [vid) lived together. "Of breasts on a tower"; "Hortelano was Belardo"]". Cf. on this last aspect Francisco de Quevedo: Historia de la vida del buscón. Edited by Ignacio Arellano. Madrid: Espasa, 2002, p. 129:

Item, noting that after they ceased to be Moors (although they still retain some relics) [the poets] have plunged into shepherds, so they walk the skinny cattle to drink their tears, shawned with their lit anomas, and so imbued in their music that they do not peace, we command that they leave such an office, pointing hermits to the friends of loneliness.

Alonso Zamora Vicente described how Lope used the form of romance to embody his own love life: «Under a Moorish or pastoral guise (the two great veils of the artistic ballads), Lope, with unbridled impetus and youthful verve with which we have seen him live, he transmutes love with Elena Osorio, exile, marriage with Isabel de Urbina ». All these romances achieved enormous popularity and were widely publicized, to the point that Lope complained that many were attributed to him that did not belong to him. This divulgation is what he remembers in a song, over time:

Since everyone my passions / my verses presume, / fault of my tired hypists, / I want to move in style and reasons.

Consequently, Lope abandoned the specific composition of personal romances between the 16th and 17th centuries (but not in his theater) and returned to them in his old age in the famous little boats: «Pobre barquilla mía...» and «I go to my solitudes...».

Rhymes

In November 1602, sandwiched between La hermosura de Angélica and La Dragontea, a collection of sonnets appeared in the Madrid printing press of Pedro Madrigal: the first collection of poems without mortar narrative that Lope published under his name. The public must have welcomed the collection of two hundred sonnets because Lope decided to publish them, without the epic poems, and accompanied by a "Second part", made up of eclogues, epistles, epitaphs. This new edition was published in Seville in 1604. The 1604 edition amended the sonnets published in 1602 in certain details and judiciously rearranged some of them. The process of accretion had not yet finished. In 1609 Lope edited them again in Madrid, with the addition of the New Art of Making Comedies. The print, though highly neglected, was well received. The text, which we can consider definitive, with the two hundred sonnets, the Second part and the New Art, was reprinted in Milan, 1611; Barcelona, 1612; Madrid, 1613 and 1621; and Huesca, 1623. In the case of the «Rhymes» we find poems that can be dated between 1578 and 1604. The two hundred sonnets cover, disorderly and inlaid with other matters, the obligatory itinerary of the Petrarchan canzonieri. The love conflicts with [Elena] Osorio gave rise to a celebrated series by Lope: the meek one. The pastoral motif is recreated in a trilogy made up of the sonnet «Vireno, that mi meek gift», preserved in the «Cartapacio Penagos» but not printed until it was published by Entrambasaguas in 1934, and sonnets 188 and 189 of the Rhymes. Sonnet 126, "To faint, to dare, to be furious," limits itself to noting contrary reactions, psychologically plausible, from the lover. The first thirteen verses have accumulated the predicate of the definition, without naming the subject. The second hemistich of the last verse convinces us that we have not heard an abstract and impersonal scholastic definition, but the artistic expression of a living experience: "whoever tried it knows it." Among all the poems that gloss these matters, 61 achieved quick and enduring fame: "Go and stay, and leave with staying." The poems added in 1604, despite their remarkable interest, have hardly aroused the curiosity of critics and readers. It begins with three eclogues of different billing, interest and depth. The New art of making comedies in this time, written at the end of 1608, is a didactic poem, a talk or a conference and, as such, escapes the strict limits of the lyric or the epic.

Sacred rhymes

The first edition is from Madrid, from 1614, with the precise title Sacred Rhymes. First part. As far as we know, there was never a second part. We are before one of those collections of poems in which the author synthesizes a whole vein of his fertile muse. Its structure corresponds to what we have been calling the lopesco songbook. It is made up of a Petrarchan canzoniere (the hundred initial sonnets) and a variety of compositions in different meters and genres: narrative poetry in octaves, glosses, descriptive romances, poems in linked triplets, lyres and songs. The Sacred Rhymes are going to widely develop the palinodia that the literary tradition of Petrarchism demanded. Not only because the initial sonnet is a rewriting of Garcilaso de la Vega's (“When I stop to contemplate my state”), but because the essential idea of offering an example of repentance for worldly love is developed here, not in a sonnet, but in the entire initial series and in many other poems that stitch the Petrarchan "canzoniere". Most of the sonnets in the Rimas sacras are written in the first person and addressed to an intimate and immediate you. The most celebrated of all, the XVIII, is a monologue of the soul, which speaks with colloquial and direct voices to a Jesus in love: "What do I have, that my friendship seeks?". Opposite these sonnets of intimacy, there are, in a smaller but relevant number, those of a hagiographic, liturgical or commemorative nature. However, some narrative poems, such as "Las lágrimas de la Madalena", the longest, are a continuation of the predominant poetic universe in the sonnets. "Tears" belongs to a kind of epic.

The Philomena

In July 1621 La Filomena appeared in Madrid with various other rhymes, prose and verses. In that same year he discovered a new Barcelona edition, the work of the most passionate lopist among Catalan printers: Sebastián de Cormellas. A miscellaneous volume, then, in which Lope rehearses, with that permanent experimental vocation that we have been pointing out, two genres that have burst onto the literary scene of his time: the novel and the mythological fable; and he tries to reply to his greatest creators and perpetual rivals: Góngora and Cervantes. The poem that gives the volume its title is presented in two different parts in meter (octaves versus silvas), genre (narrative versus symbolic fable of literary polemic) and intention. The first part, in three songs, narrates the tragic story of Philomena, raped and mutilated by her brother-in-law Tereo, according to the well-known Ovidian story from book VI of the Metamorphoses. "The fortunes of Diana", a short novel, is not exempt from polemical eagerness and spirit of emulation either. We are facing an almost final blow of the tail of the bitter dispute that arose as a result of the publication of Don Quixote. First part (1605) and the response of Lope's circle in the apocryphal, signed by Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda (1614). But it is not our purpose to comment on the narrative art of the «Novels to Marcia Leonarda», but to point out its lyrical dimension. Its main core is a new installment of pastoral romances. "La Andromeda" is a poem related to "La Filomena" although somewhat shorter: 704 verses in a single song. He narrates with his usual ease, and with fewer digressions than usual, the story of Perseus, the death of Medusa, the birth of Pegasus, the emergence of the source of Hypocrine. Much more interesting are the poetic epistles that follow, including two that are not by Lope.

La Circe

La Circe con otros poemas y prose appeared in Madrid in 1624. La Circe is a miscellaneous volume, twin of La Filomena, although with nuances and differences. The poem that gives the volume its title is a replica and, in a certain way, an overcoming of the model of the mythological fable set by Góngora. In two ways: in its length and complexity (three songs with 1,232, 848, and 1,232 verses) and in its moral scope. An omniscient narrator introduces the reader to the tragic fall of Troy. The same narrator tells us how Ulysses' soldiers open the skins of Aeolus who has locked up the winds and, in the midst of the storm, they reach the island of Circe. We witness the transformation of soldiers into animals. Circe defeated, Ulysses' friends recover their original image. Ulysses departs, but he still has to descend to hell to consult his future with the soothsayer Tiresias. "The White Rose" is the second mythological poem in this volume, shorter and more concentrated than La Circe, with 872 verses in octaves. It brings together in rapid succession a series of mythical episodes linked to the goddess Venus. As in La Filomena, Lope reserved the three novels "To Mrs. Marcia Leonarda" to insert the contribution of Castilian verses that we have in all of his collections of poems. He does not abuse them: three or four original poems host each of the stories. The six epistles in verse of La Circe (there are three more in prose) are a prolongation and purification of the genre and the poetic spirit that we saw in La Filomena.

Divine Triumphs

After ten years as a priest, in the midst of the literary controversies surrounding culteranismo, Lope returned to sacred poetry as another instrument to approach political and ecclesiastical power. These circumstances are evident in Triunfos divinos (Madrid, 1625), dedicated to the Countess of Olivares. The extensive poem that gives the volume its title is an a la divino version of Petrarch's Triomphi. The liveliest part of the collection of poems are the sonnets that continue the penitential and introspective line of the 1614 volume. With its own title page, addressed to Queen Isabel de Borbón, the volume closes with a short epic poem (three songs; 904 verses) entitled The Virgin of the Almudena.

Apollo's Laurel

The campaign with which Lope tries to project his figure among high places and in literary circles should include the publication of Laurel de Apolo (1630). The central poem, which gives the volume its title, is the act of some courts on Parnassus. For this transcription he uses the silva as the stanza. Lope proposed to praise the poets of his time and he did so. Throughout ten silvas, about three hundred Spanish and Portuguese vates, thirty-six Italians and French and ten illustrious painters parade. Within the long catalog of poets some mythological fables are inserted, two of them with their own identifying title (Diana's Bath, El Narciso). Lope also takes advantage of this to indirectly attack his rival for the position of Chronicler of the Kingdom of Castilla y León, José Pellicer de Salas y Tovar, who was also one of the commentators of his great enemy, Luis de Góngora, whose style is criticized also in the Apollo's Laurel through his bad followers. The volume of the Apollo's Laurel, although occupied for the most part by the long poem described, has an appendix that is not without interest. There is found La selva sin amor, a pastoral eclogue, a silva, an epistle and a handful of eight sonnets, among which the anticulteran satires have always stood out: "Boscán, we are late. Is there an inn...?".

The Eclogue to Claudius

The Eclogue to Claudio, of which there is an autograph copy in the Códice Daza with many variants, was probably composed in January 1632 and printed loose without a year addressed to the scholar Lorenzo Ramírez de Prado; then it appeared within the posthumous La Vega del Parnaso (1637). It is a fundamental work of the last Lope, when he has already been disappointed in his last and vehement illusions: reaching the permanent position of chaplain to the Duke of Sessa or being a chronicler of Felipe IV.

Thus, after so many dilations / with peaceful modesty suffered, / forced and impeled / of so many scoundrels, / leave among superb humilitys / of the mine of the soul the truths. [...] / I go on the path of dying clearer / and of all hope I retire; / that I only grasp and look / where everything stops; / for I have never seen that afterward I lived / who did not look first that I died

As Juan Manuel Rozas, the main scholar of this highly cited work, writes, he expresses a disappointment «surprising due to its intensity in the mouth of the creator of a theater that propagates the monarchical-aristocratic principle and, at the same time, the theocentric monarchy. It is about the disenchantment of the vitalist and winner Lope de Vega. I've called that loop senectute. It has its beginnings in the Corona tragica (1627) and the Laurel de Apolo (1630), it is shown clearly, since 1631, through the Dorothea (1632) and the Rimas de Burguillos (1634), to have its most direct expression, almost monographic, in the poetry gathered in La Vega del Parnaso (1637) ».

In its subject matter, as heterogeneous and miscellaneous as is typical of the author, its extensive autobiographical content stands out (his friend Juan Pérez de Montalbán called it the «epitome of his life») and misleads as to its title: it is not about not an eclogue in dialogue but an epistle. Its thematic axes, according to Rozas, are three of a symmetrical type: young Lope / old Lope; young writers / Lope creator of the new comedy; Lope's life and work at the service of his nation and the Crown / contempt for him, old man, by the Court. Its structure is also triple; according to Rozas, "a quick review of his life, a very detailed account of his learned work and an assessment of his theater"; actually conceals an apology pro domo sua , something quite common in the work of his last years. Lope talks to Claudio Conde, the only friend of his youth who has survived so that he is therefore an exceptional witness to the events.

Criticism of his disciples in theater and lyrical poetry is based on his lack of «concept» and realism, on his excessive philosophicalism and on the abuse of formal ornamentation, scenery and decorations («appearances»)...critiques in the background directed at gongorismo or culteranismo and the school of Pedro Calderón de la Barca:

Well it is true that I fear the lucimiento / of so many metaphysical violence / founded in appearances, / deceit that makes the wind / (here the bell) in the ear / it seems conceto and is sound.

Against all this, he opposes his idea of poetry in two words: «Purity and harmony». Like Quevedo, he seeks solace in the old stoicism: "Fuera esperança, if I've had any: / I no longer need Fortune"; or "Claudio, that's how all who live change: / I don't know if I'm the one".

The plain of Parnassus

Among Lope's collections of poems, this one presents a very peculiar story. The nucleus of it is made up of a series of lyrical compositions of a certain length printed as loose sheets or pamphlets of few pages in the last years of the poet's life. Lope thought of giving the printer El Parnaso , but he did not carry out his proposal. The new collection of poems did not see the light of day until, after the author died, his friends and heirs published it in 1637 in the Kingdom Printing Office under the title La vega del Parnaso . In La Vega works of very different depth, intention and importance were collected. Single prints prior to 1633, which have already been mentioned, were included. Ancient texts were recovered. Occasional poems from Lope's last stage accumulated, among them a heartfelt elegy, "Elogio en la muerte de Juan Blas de Castro", in which he recalled the times when this musician was his confidante in the court of Alba de Tormes, where both worked for the Duke, of his love affairs with Filis, and how he went to her house to kiss the hand of the deceased, who had set so many of his songs or tones to music; he was also the composer of the incidental music for many of his theatrical pieces, and had gone blind in his later years, like Marta de Nevares. Some works written in the last months of the poet's life were also grouped together. This mix of drama and lyrics is entirely foreign to Lope's editorial habits. La vega del Parnaso is Lope's penultimate lyrical revolution. In several poems he employs two types of six-line lyre. With this meter he seeks a more concise expression. It is a momentary abandonment of his long career as a Petrarchan and loving poet to try a poetry turned towards the social that will earn him the respect and help of the court. One of the key themes of the collection of poems is the awareness of death.

Human and divine rhymes by Mr. Burguillos

In November 1634, at the Kingdom Printing Office, at the expense of Alonso Pérez, the last collection of poems that Lope would see during his lifetime was printed: Rimas humanas y divinas del licenciado Tomé de Burguillos. The book has the usual structure of the lopesco songbooks: a Petrarchan songbook (made up of most of the 161 sonnets), which is fundamentally parodic and humorous, since it focuses on a washerwoman from Manzanares, Juana, whom the author, a mask or heteronym of Lope, the poor student Tomé de Burguillos. Along with these poems there are other epigrammatic, humorous, serious, disappointed, satirical, humorous, religious and even philosophical poems, which belong to the quiet cycle de senectute lopesco, as well as an exceptional comic-burlesque epic, La Gatomaquia, in seven silvas, undoubtedly the most perfect and finished example of the epic genre that came from Lope's pen, starring cats. On the cover appears the "Licenciado Tomé de Burguillos" and an engraving, presumed portrait of the same; the synthetic biography of him is given to us in the "Warning to the reader." Burguillos, parallel in a certain sense to the figure of the grace of his comedy, embodies the anti-heroic, skeptical and disappointed vision of the old Lope, who parodies his own biography and his literary creation. However, the approval of the author's friend, Francisco de Quevedo, suggests that his style is very similar "to the one that flourished without thorns in Lope de Vega". Burguillos traces a Petrarchan canzoniere in the key of parody, self-parody.

Lyrics in the theater

With Lope de Vega, around 1585, the Spanish theater recovered its primitive lyrical vocation. In the end, the creators of the new comedy are the same ones who have made Moorish and pastoral romances fashionable. Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo already perceived that many of Lope's comedies were inspired by songs of a traditional nature. In El caballero de Olmedo, for example, although there was a real tragic historical event, the murder of the gentleman Juan de Vivero, the matter gave rise to some popular seguidillas and an anonymous romance that are cited in the text and give much of their atmosphere to the comedy. In others, for example in Fuenteovejuna, it no longer introduces, but instead imitates traditional ballads, which appear on stage sung by musicians ("Al val de Fuenteovejuna / the girl with low hair.... 4;); other times he uses popular songs, such as the one about the harvest in Peribáñez and the commander of Ocaña. Many old traditional Castilian lyric (villancicos, serranillas, wedding songs, seguidillas...), now disappeared, are has been preserved or reconstructed thanks to the inclusion of Lope and his imitators in his comedies.

On the other hand, Lope inserts in his comedies passages of cultured lyric that use above all the sonnet (when there are monologues and the characters are left alone) or when the action calms down in comedies in which the strength is found in the characterization, as in the case of El perro del hortelano, in which it includes no less than five. He also uses the lyric in the tenths (which "are good for complaints", as he indicates in the New Art of Making Comedies) and less frequently in the romances and real octaves, which used only for "relationships", that is, when one character tells something to another.

Epic work

The snapdragon

Lope devoted a considerable part of the efforts of his best years to becoming Spain's quintessential cultured epic poet. The first attempt of his published by him, La dragontea , had notable problems in the appearance of him. Permission to publish it was denied by the Castilian authorities in 1598, which is why the book had to be printed in Valencia. Relying on this Valencian permit, Lope once again requested authorization to publish it in Castilla. Not only was the new edition not allowed, but the copies that were circulating in the kingdom of Castile were ordered to be collected. He did not give up the poet and, hidden behind The beauty of Angélica and the two hundred sonnets, he published it in Madrid in 1602.

In the 732 octaves (5856 verses) of ten cantos, he narrates the forays of sir Francis Drake, accompanied by "Juan Achines", that is, John Hawkins, through American lands in 1595 and 1596 (Canary Islands, Puerto Rico, Panama, Nombre de Dios and Portobelo), his persecution at the hands of General Alonso de Sotomayor, and his death in Portobelo poisoned by his own (actually, dysentery), being inspired, as affirms Lope himself, in a Relationship composed by the Royal Court of Panama using reliable testimonies from several people present at the events, and, perhaps, in the data offered in the Captain's Speech Francisco Drake and San Diego de Alcalá composed by Juan de Castellanos, which were corroborated by those offered by the Expeditio Francisci Draki Equitis Angli in Indias Occidentales Anno MDLXXXV (1588) by Walter Bigges.

The poem was intended to reflect popular anti-English sentiment; & # 34; never the English, if it is not for inclement of the sea or for great inequalities in the people, have had good success & # 34;, he writes in the prologue. Despite everything, it did not achieve success and it was only reprinted the following century, in the Obras solas of 1776.

Isidro

The most lively of the hagiographic poem Isidro (Madrid, 1599), about the life of the patron saint of Madrid, San Isidro Labrador, written in limericks along ten songs are, without dispute, the abundant fragments in which the poet approaches the rural universe in which the saint moves; Indeed, Lope wholeheartedly loved the simple life of the peasants and yearned all his life for direct contact with nature. But this biographical poem is something more than that, since it is solidly documented: he read everything previously written about the saint and had access to the papers for the cause of beatification collected by Father Domingo de Mendoza, pontifical commissioner for the beatification of Isidro.

The beauty of Angelica

This poem was published in 1602, together with Rhymes and La dragontea; it is dedicated to his Sevillian friend, the poet Juan de Arguijo; in the prologue Lope says that he wrote it in the moments that the marine life left him free, "over the waters, between the rigging of the galleon San Juan and the flags of the Catholic King", continuing the fringes of the story of Angélica that Ludovico Ariosto traced in his Orlando furioso, since he himself proposed to other mills that they continue if they did better. He transfers the story of Angélica to Spain and outlines with her adventures and misadventures twenty cantos in real octaves.

Jerusalem conquered

In 1604, in the prologue to the Seville edition of Rhymes, Lope announced the imminent appearance of a new epic poem. The work did not see the light of day until February 1609, under the title The Conquered Jerusalem, a Tragic Epic. The text that was printed does not have sixteen books, but twenty. Rafael Lapesa suggests that the original text ended with the wedding of the daughter of Alfonso VIII with Ricardo Corazón de León in the recently liberated Jerusalem, but to match the number of songs in Torquato Tasso's poem (Gerusalemme liberata, 1581), Lope added four in which he had to narrate the abandonment of the company by the Crusaders.

This heroic poem, dedicated to Felipe III, is of more than doubtful historicity: it exposes the false military presence of the Castilian king Alfonso VIII (represented in a magnificent preliminary engraving and who is supposed to be the direct ancestor of Felipe III) in the ill-fated Third Crusade with the purpose of liberating the Holy Land from Muslim power and is accompanied by not a few scholarly notes; there were Spaniards in the undertaking, it is true, but not the king himself. Consequently, it turns out to be a poem of commendatory purpose as well as "a nationalist revision of the Tasso epic, and of history itself", although also, according to modern criticism, a "story of stories". Each of his twenty songs in real octaves is preceded by an "argument"; in prose summarized in the form of a sonnet and the work is preceded by a praise from his friend, the painter and poet Francisco Pacheco. In it he ponders "the much imaginative" and "understanding and art so together, so perfect" of the author, along with his well-achieved ease. Lope reciprocated by dedicating his comedy La gallarda toledana to Pacheco in Part XIV of his comedies and with praise in his Laurel de Apolo . Furthermore, Antonio Carreño, modern editor of the work, affirms that

The genealogical, mythical discourse alternates in [the play] with the nationalist and ethnic. The desire to serve the homeland, to remove the facts of its heroes from oblivion, to contradict the silent version of the foreign historians who, when describing the heroic facts of the crusaders, silence the Castro presence, also moves the traits of the pen of this abhorrent narrator. And, in spite of becoming Lope the historical narrative with the fabulda, and mixing indistinctly both as possible, justifies the hand of the Poetry of Aristotle the validity of alternating factum —narration of a fact—with the poesis —the universal truth that transcends the particular fact—

In fact, Aristotle, in his Poetics, distinguishes History and Poetry saying that "one says what has happened and the other what could happen" and for this reason "poetry is more philosophical and elevated than history, since poetry rather says the general, and history, the particular." But this warning by Lope did not discourage his critics, in in particular the humanist Juan Pablo Mártir Rizo, who pointed out its defects in several passages of his Poetics of Aristotle translated from Latin (1623). "The hybrid mixture of diverse stories, the lack of characterization, the absence of a hero (individual or collective) and, above all, the extensive digressions, sometimes erudite, annoying". Among these stand out the narratives, like the story of Alfonso VIII's love affair with the Jewish woman Raquel in Toledo, a matter already dealt with by Lope and which is like a separate poem; as for the diffuse prominence, it is shared by King Felipe II of France, Ricardo Corazón de León and Alfonso VIII himself; the final songs appear as surplus, with other structure and composition flaws that do not tarnish the verve and poetic brilliance of the author, whose vivid and prodigious imagination achieves admirable and brilliant passages. But Lope himself did not hide the damage that criticism would do him in Spain, and at the end of the last canto he wrote:

I always of persecuted envy, / alien in my homeland and banished, / to Ovid only in this likeness, / though by the strangers always honored; / alone my favored truth / and the mortal power deceited... / But what can you expect from your mountain / wit that walks through Spain?

Such a complex epic was published in three volumes by the lopista Joaquín de Entrambasaguas (Madrid: CSIC - Instituto "Miguel de Cervantes", 1954) and more recently by Antonio Carreño (Madrid: Fundación José Antonio Fernández de Castro, 2003, volume III of the Complete Works of the Castro Library).

Dramatic work

The Creation of the New Comedy

Lope de Vega created the classical Spanish theater of the Golden Age with an innovative dramatic formula. In this formula he mixed the tragic and the comic, and broke the three units advocated by the Italian school of poetics (Ludovico Castelvetro, Francesco Robortello) founded on Poetics and Rhetoric of Aristotle: unit of action (that a single story is told), unit of time (in 24 hours or a little more) and of place (that it takes place in a single place or in nearby places).

Regarding the unit of action, Lope's comedies use the imbroglio or Italian imbroglio (telling two or more stories in the same work, usually a main one and a secondary one, or a carried out by nobles and another by their commoner servants). That of time is recommended but not always followed, and there are comedies that narrate the entire life of an individual, although he recommended matching the passage of time with the intermissions. Regarding the place, it is not complied with at all.

What's more, Lope de Vega does not respect a fourth unit, the unit of style or decorum that is also outlined in Aristotle, and mixes the tragic and the comic in his work and uses a polymetric theater that uses different types of verse and stanza, depending on the background of what is being represented. He uses romance when a character makes relationships, that is, tells facts; the eighth real when it comes to making lucid relationships or descriptions; rounds and limericks when it comes to dialogues; sonnets when it comes to introspective monologues or you expect or when the characters have to change costumes behind the scenes; tenths if it is complaints or regrets. The predominant verse is the eight syllable, somewhat less the hendecasyllable, followed by all the others. It is, therefore, a polymetric and little academic theatre, unlike classical French theatre, and in that sense it is more like Elizabethan theatre.

On the other hand, he dominates the theme over action and action over characterization. The three main themes of his theater are love, faith and honor, and it is interspersed with beautiful lyrical intermissions, many of them of popular origin (Romancero, traditional lyric). Themes related to honor are chosen preferably ("they move all people with force," writes Lope) and satire that is too overt is avoided.

Lope took special care of the female audience, who could make a performance fail, and recommended "deceiving with the truth" and making the audience believe in outcomes that then did not occur until at least halfway through the third day; He recommended some tricks, such as transvestite actresses with masculine costumes, something that excited the libidinous imagination of the male audience and that in the future would spread in the universal comic theater as a common script trick in comedy of all times: war of the sexes, that is, changing the masculine and feminine roles. Impetuous women who behave like men and indecisive men who behave like women. Lope recommends all these precepts to those who want to follow his dramatic formula in his New art of making comedies in this time (1609), written in blank verse with couplets for a literary academy.

Lope against the publishers of his plays

Lope frequently complained that the manuscripts he gave to the "authors" (theatrical impresarios, in the language of the time) were altered, defaced, cut and adapted and, frequently, taken to the printer without his permission as which one had remained This was the case since in 1604 they began to publish Parts of his dramatic works. Through the mouth of Belardo, Lope says in Los Burgos de Lerma (1613):

And as for the first / prints run light, / I come to be soap: / mine the signs are / and yours are scissors.

Tired of being printed without the slightest care or correction, he sued the publisher Francisco de Ávila, who prepared the edition of the Sixth part of his Comedias and the Flor de las comedias de diferentes autores, both from 1615, trying to prevent him from publishing the seventh and eighth Parts without prior revision; but Ávila won the lawsuit on the basis of rights acquired when he bought the original manuscripts from the "authors" Baltasar de Pinedo and Luis de Vergara, to whom Lope had sold them.

The Phoenix complained bitterly about this when he managed to edit his comedies himself from the ninth Part, in 1617; in his foreword he lamented "the cruelty with which my opinion is torn apart by some interests" and, to avoid this, he continued to edit his own comedies up to volume XX. Since he was convicted of libel, Lope has never had any confidence in the courts; he dedicates an ironic sonnet to lawsuits in his Human and Divine Rhymes :

Pleths, to your procedural gods / humble confess my ignorance; / do ye of anatomy hope, / even the detrimental judicial.

And in the comedy Friendship and Obligation, he speaks through the mouth of Belardo:

I'm sorry to leave you like this / and that the Court doesn't see, / that I'm afraid even the village / come some lawsuit behind me... / Before I flee from the people; / that with not being delinquent / everything I love vara. / There is no pillar that I do not imagine / that is a solicitor; / there I will be better. Oh, God your things go!

A ban in 1625 on publishing comedies and hors d'oeuvres hampered his purpose; then, like other authors, he managed to circumvent the law by publishing them loosely within poetic miscellanies such as La Filomena, La Circe, El laurel de Apolo and La vega del Parnaso (in which he included no fewer than eight) until the ban was finally lifted in 1634. Lope had already prepared parts XXI to XXIV, but he died before seeing them printed.

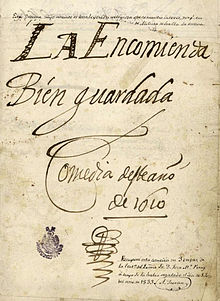

Classification and main dramatic works

Lope's dramatic works were composed only for the stage and the author did not reserve any copies. The copy suffered from the cuts, adaptations, extensions and retouching of the actors, some of them also comedy writers.