Lombards

The Lombards (in Latin, langobardi, from which the alternative name of longobards comes) were a Germanic people originating from northern Europe who settled in the Danube valley and from there invaded Byzantine Italy in AD 568. C. under the leadership of Alboino. They established the Lombard kingdom of Italy, which lasted until AD 774. C., when it was conquered by the Franks.

Legendary origins and name

The full account of Lombard origins, their history and practices, is found in Paul the Deacon's Historia gentis Langobardorum (History of the Lombards), written in the 8th century. Paul's main source for Lombard origins, however, is the century work VII Origo gentis Langobardorum (Origin of the Lombard people).

The Origo tells the story of a small tribe called the Winnili who lived in southern Scandinavia (Scadanan) (the Codex Gothanus writes that the Winnili first inhabited near a river called the Vindilicus on their extreme border of Gaul.) The Winnili divided into three groups and one part left the homeland to seek foreign fields. The reason for the exodus was probably overpopulation. The people who left were led by the brothers Ybor and Aio and their mother Gambara and reached the lands of Scoringa, perhaps the Baltic coast or the Bardengau on the banks of the Elbe. Scoringa was ruled by the Vandals and their chiefs, the brothers Ambri and Assi, who gave the Winnili a choice between tribute or war.

The Winnili were young and brave and refused to pay tribute, saying "It is better to preserve liberty by arms than to stain it by paying tribute". The Vandals prepared for war and consulted to Godan (the god Odin), who replied that he would grant victory to those whom he saw first at dawn. The winnili were fewer in number, and Gambara sought the help of Frea (the goddess Frigg), who advised her that all Winnili women should tie their hair under their faces like beards and march together with their husbands. At dawn, Frea turned her husband's bed to the east and woke him up. So Godan saw the winnili first, and asked, "Who are these with long beards?" and Frea replied, "Lord, you have given them the name, now grant them victory as well." From then on, the Winnili were known as the Langobards (Latinized and Italianized as Lombards).

When Paul the Deacon wrote the History between 787 and 796, he was a Catholic monk and devout Christian. Thus, he thought the pagan stories of his people were "silly" and "ridiculous". Paul explained that the name "Langobard" came from the length of their beards, from the Germanic words lang 'long' and bard 'beard'. One modern theory suggests that the name Langbard comes from Langbarðr, a nickname of Odin. Priester claims that when the i>winnili changed their name to "Lombards", they also changed their ancient cult of agricultural fertility to the cult of Odin, thus creating a conscious tribal tradition. Fröhlich reverses the order of events in Priester and states that with the worship of Odin, the Lombards grew their beards to resemble the Odin of tradition, and their new name reflected this. Bruckner notes that the Lombard name stands in a close relationship to the veneration of Odin, whose many names include "he with the long beard" or "he with the gray beard", and that the Lombard name Ansegranus ('he who has the beard of the gods') shows that the Lombards had this idea of their chief deity.

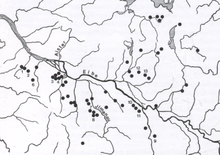

Archaeology and migrations

From the combined testimony of Strabo (AD 20) and Tacitus (AD 117), the Lombards dwelt near the mouth of the Elbe River shortly after the beginning of the Christian era, near the Caucians. Strabo states that the Lombards lived on both banks of the Elbe. The German archaeologist Willi Wegewitz defined several Iron Age burial sites on the Lower Elbe as Langobardic. VI a. C. up to III d. so a break in settlement seems unlikely. The lands of the lower Elbe fall into a zone of the Jastorf culture and became Elbe Germanic, differing from the lands between the Rhine, Weser, and Sea Seas. North. Archaeological finds show that the Lombards were an agricultural people.

The first mention of the Lombards occurs between the year 9 AD. and 16 AD, by the Roman court historian Veleyus Paterculus, who accompanied a Roman expedition as prefect of cavalry. Paterculus described the Lombards as "fiercer than the ordinary German savages". Lombards among the Suevian tribes, and subjects of Marobod the King of the Marcomans. Marobod had made peace with the Romans, and therefore the Lombards were not part of the German confederation under Arminius at the Battle of the Forest of Teutoburg in the year 9. In the year 17, war broke out between Arminius and Marobod. Tacitus says:

Not only the cherubim and their confederates took the weapons, but the senones and the longobards, both the Sueva nations, rebelled against him from the sovereignty of Marobod... The armies... were stimulated for their own reasons, the cherubim and the Lombards fought for their old honor or their newly acquired independence...

In 47, a fight broke out between the Cheruscans and they expelled their new leader, Arminio's nephew, from their country. The Lombards appear on the scene with enough power, it seems, to control the fate of the tribe that, thirty-eight years earlier, had led the fight for independence, as they restored the deposed chief. In the middle of the century II, the Lombards also appear in the Rhineland. According to Ptolemy, the Lombard Suevi settled to the south of the Sicambrians, but remained on the Elbe, between the chauci and the Suevi, indicating Lombard expansion. The Codex Gothanus also mentions Patespruna (Paderborn) in connection with the Lombards. Cassius Dio informs us that just before the Marcomannic Wars, six thousand Lombards and the ubians crossed the Danube and invaded Pannonia. The two tribes were defeated, so they gave up their efforts and sent Ballomar, king of the Marcomanni, as ambassador to Aelius Basao, who was then administering Pannonia. Peace was made and the two tribes returned to their home, which in the case of the Lombards was in the lands of the lower Elbe. Around this time, Tacitus, in his work Germania (98 AD. C.), describes the Lombards as follows:

To the langobards, on the contrary, their small number distinguishes them. Although surrounded by a host of more powerful tribes, they are safe, not subjecting, but challenging the dangers of war.

From the II century onwards, many of the Germanic tribes of the time of Emperor Tiberius began to form large tribal unions, resulting in the Franks, Alemanni, Bavarians, and Saxons. The reason why the Lombards disappear as such from Roman history in the period 166–489 might be that they dwelt so deep in Inner Germania that they were only detected when they reappeared on the banks of the Danube, or because the Lombards found themselves subjected to a larger tribe, probably the Saxons. It is, however, quite likely that when the bulk of the Lombards emigrated, a considerable part remained behind and more they were later absorbed by the Saxon tribes in the region, while only the emigrants retained the name Lombards. However, the Codex Gothanus writes that the Lombards were subdued by the Saxons around the year 300, but they rose again against the Saxons under their king Agelmund. In the second half of the IV century, the Lombards left their home, probably due to poor harvests, and embarked on their migration.

The migration route of the Lombards, from their homeland to Rugiland in 489, included several places: Scoringa (believed to be their land on the shores of of the Elbe), Mauringa, Golanda, Anthaib, Banthaib and Vurgundaib (Burgundaib). According to the Ravenna Anonymous, Mauringa was the land east of the Elbe.

The crossing to Mauringa was very difficult, the assipitti (usipetes) denied them passage through their land; a fight was arranged between the strongest man of each tribe. The Lombards were victorious, they were allowed through and the Lombards reached Mauringa. The first Lombard king, Agelmund, of the house of Guginger, ruled for thirty years.

The Lombards left Mauringa and reached Golanda. Scholar Ludwig Schmidt believes this was further east, perhaps on the right bank of the Oder. Schmidt considers the name to be the equivalent of Gotland, meaning simply 'good land'. This theory is highly plausible., Paul the Deacon mentions an episode of the Lombards crossing a river, and the Lombards could have reached Rugiland from the Upper Oder through the Moravian Gate.

Leaving Golanda, the Lombards passed through Anthaib and Banthaib and reached Vurgundaib. Vurgundaib is believed to be the ancient lands of the Burgundians. At Vurgundaib, the Lombards were defeated by the "Bulgars" (probably Huns); King Agelmund was assassinated. Laimicho was later promoted to power; he was in his youth and wished to avenge the death of Agelmund. The Lombards themselves were probably subjects of the Huns after the defeat, but the Lombards rose again against them and defeated them with great slaughter. The victory gave the Lombards a great booty and confidence because they "...became more daring when it came to facing each other in war".

In the 540s, Alduin (ruled 546-565) led the Lombards across the Danube back into Pannonia. They settled there thanks to a foedus of 540, as Justinian encouraged them to fight against the Gepids to have them as allies and serve as a barrier to Italy against invasions by other barbarian peoples. Since Justinian had supported them in a war against the Gepids, they fought the Ostrogoths in return.

The kingdom of the Lombards in Italy

In 560 a new and energetic king arose: Alboíno, who defeated his Gepid neighbours, made them his subjects and, in 566, married his king Cunimund's daughter, Rosamunde. In the spring of 568, Alboíno, assisted by some contingents from other Germanic tribes, invaded Italy by forcing the limes of Friuli. Around one hundred thousand Lombards crossed the Julian Alps and invaded northern Italy (the Roman population in northern Italy was approximately two million people) due to pressure from the Avars. At that time Longinus, who had succeeded Narses in the government of Italy with the title of exarch, did not expect this invasion. In the summer of 569, the Lombards conquered the Roman center of northern Italy, Milan. The area was then recovering from the terrible Gothic wars, and the small Byzantine army left to defend it could do nothing.

Pavia subsequently fell, after a three-year siege, in 572, becoming the first capital of the new Lombard kingdom of Italy. The following year, the Lombards penetrated further south, conquering the Tuscany region. Later, the Lombard tribes also settled in central and southern Italy establishing the duchies of Spoleto and Benevento, which soon became semi-independent. The Byzantines managed to retain control of the regions of Ravenna and Rome, linked by a narrow corridor that ran through Perugia.

When they entered Italy, some Lombards retained their native form of paganism, while some were Arian Christians. Hence, they did not have good relations with the Catholic Church, which they persecuted with the zeal of neophytes. Gradually, they adopted Roman titles, names and traditions, and partly converted to Orthodoxy (VII), not without a long series of religious and ethnic conflicts.

As a result of these events, thirty-six independent duchies were formed in the territory conquered by the Lombards, but this dismemberment was detrimental to them and fatal to Italy. Its leaders settled in the main cities. The king ruled over them and administered the land through emissaries called gastaldi. This subdivision, however, together with the duchies' independent lack of docility, deprived the kingdom of its unity, weakening it even in comparison to the Byzantines, especially after they began to recover from the initial invasion. This weakness became even more evident when the Lombards had to face the growing power of the Franks. In response to this problem, the kings tried to centralize power over time, but lost control of Spoleto and Benevento for good in the attempt.

The Lombard invasion, on the other hand, destroyed the limes of Friuli and the strongholds of Veneto. Consequently, this area was left open for other barbarians to cross the Alps and invade. This was done by the Avars and the Slavs, who attacked the plains, sometimes reaching the Adriatic Sea.

Social Structure

Language

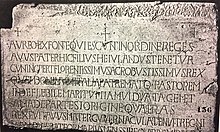

The Lombard language is extinct. The Germanic language declined after the 7th century century, but was able to continue to retain scattered use until around 1000. The Lombard language written is only fragmentarily preserved, the main evidence being individual words quoted in Latin texts. In the absence of Lombard texts, it is not possible to reach any conclusion about the syntax and morphology of the language. The genetic classification of the language is necessarily based entirely on phonology, since there is evidence that Longobardic participated in it, and indeed shows some of the earliest evidence for High-German consonant shift, which is classified as a Elbe Germanic or Upper German dialect.

Longobardic fragments are preserved in runic inscriptions. Among the primary source texts are brief Old Futhark inscriptions, including the "Schretzheim bronze capsule" (c. 600). There are a number of Latin texts that include Lombard names, and Lombard legal texts contain terms taken from the vernacular legal vocabulary. In 2005, there were some claims that the inscription on the Pernik sword may be Lombard.

Society of the migration period

Lombard kings can be traced back to around 380 AD and thus to the beginning of the Great Migration. Kingship developed among the Germanic peoples when the unity of a single military command was deemed necessary. Schmidt believed that the Germanic tribes were divided by cantons and that the earliest government was a general assembly that selected the heads of the cantons and the warlords of the cantons (in times of war). Such figures were probably selected from a caste of nobles. As a result of the wars of his wanderings, royal power developed in such a way that the king became the representative of the people; but the influence of the people over the government did not completely disappear. Paul the Deacon gives an account of the Lombard tribal structure during the migration:

...to be able to increase the number of their warriors, to grant freedom to many of those who release from the yoke of slavery, and that the freedom of these can be considered established, they confirmed in their way accustomed to an arrow, uttering certain words of their country in confirmation of the fact.

Complete emancipation seems to have been guaranteed only between the Franks and the Lombards.

Catholic Kingdom Society

Lombard society was divided into classes comparable to those found in the other Germanic kingdoms: Frankish Gaul and Visigothic Hispania. The Lombards confiscated the land and the native nobility, be it Roman or Gothic, took over. This noble class occupied the upper echelon of society. Below them, there was a class of free men; then there were the serfs, not slaves but not free either, and finally, the slaves. The Lombard aristocracy was poorer, more urbanized, and less tied to the land than the other Germanic peoples. In addition to the richest and most powerful dukes and the king himself, Lombard nobles tended to live in cities, unlike their Frankish counterparts. Their land holdings were little more than twice the land owned by a merchant, which is a far cry from the provincial Frankish aristocracy, who owned vast tracts of land hundreds of times the size of men of the next social class below. The aristocracy of the 8th century depended largely on the king for income related especially to judicial duties: many Lombard nobles are mentioned in contemporary documents as iudices (judges), even when their positions also had important military and legislative functions.

The freemen of the Lombard kingdom were considerably more numerous than among the Franks, especially in the VIII century, when they were nearly invisible in surviving documentary evidence for the latter. Small landowners, owner-cultivators, and renters are the most numerous types of people in the remaining diplomas of the Lombard kingdom. They may have owned more than half the land in Lombard Italy. Free men were exercitales and viri devoti, that is, 'soldiers' and 'devoted men' (a military term like "servants"); they formed the levy of the Lombard army and were, albeit infrequently, sometimes called to serve, although this seems not to have been their preference. The small landowner class, however, lacked the necessary political influence with the king (and the dukes) to control the politics and legislation of the realm. The aristocracy was more rigorously political in Italy than in contemporary Gaul and Hispania.

The urbanization of Lombard Italy was characterized by the città ad isole ('cities on islands'). It turns out from archeology that the great cities of Lombard Italy —Pavia, Lucca, Siena, Arezzo, Milan— were themselves formed by small urbanization islands within the ancient Roman walls. The cities of the Roman Empire have been partially destroyed in the series of wars of the centuries V and VI. Many sectors were left in ruins and the ancient monuments were turned into grassy fields used as pastures for animals, thus the Roman Forum became the campo vaccinio: the 'cow field'. The portions of the cities that remained intact were small and modest, containing a cathedral or main church (often sumptuously decorated), and a few public buildings of the aristocracy. In the end, the inhabited parts of the cities were separated from each other by strips of grass even within the city walls.

At this time, the capital of the Lombards, Pavia, had a special importance. It was the administrative center where the Royal Chamber was located, that is, the treasury or financial body of the Lombard kingdom; but it was also a religious metropolis, first of Arianism and then of Catholicism, in which bishops' synods were held.

Religious history

Paganism

Early indications of Lombard religion show that, while in Scandinavia, They worshiped the Vanir from German mythology. After settling along the Baltic coast, through contact with other Germanic peoples, they adopted the cult of the Aesir, a change that represented the cultural transition from an agricultural society to a warrior society.[citation needed ]

After their migration to Pannonia, the Lombards came into contact with the Sarmatians. From these towns they borrowed customs and certain religious symbols. The most prominent was a funeral ritual by which a pole crowned with the effigue of a bird was placed in the house of a man killed on the battlefield whose body could not be recovered. Usually the bird was oriented towards the point where the warrior had fallen.[citation needed]

Christianization

Established in Pannonia, the Lombards were introduced to Christianity for the first time, and some of their nobles were baptized, but their conversion was purely nominal. During Wacho's reign, they considered themselves Catholics and allies of the Byzantine Empire, but King Alboino converted to Arian Christianity as an ally of the Ostrogoths and soon after they invaded Italy. All these conversions affected, above all, the aristocracy; the common people remained mostly pagan.

In Italy, however, the Lombards were heavily Christianized and pressure to convert to Catholicism was great. With the Bavarian queen Teodelinda, a Catholic, the monarchy was brought under strong Catholic influence. After initial support for the followers of the Three Chapters schism, Theodelind turned to Pope Gregory I. In 603, Adaloald, the heir to the throne, received a Catholic baptism. For the next century, Arianism and paganism continued to exist in north-eastern Italy and in the duchy of Benevento. A succession of Arian kings were militarily aggressive and posed a threat to the Papacy in Rome. In the 7th century century, the nominally Christian aristocracy of Benevento still practiced pagan rituals, such as sacrifices in "sacred" groves. By the end of Cunipertus's reign, however, the Lombards had become more or less completely Catholic. Under Liutprando, Catholicism became the predominant religion as the king sought to justify his title of rex totius Italiae by uniting the south of the peninsula with the north and uniting his Roman and Germanic subjects into a single Catholic state.

Christianity in Benevento

The duchy and eventually principality of Benevento in southern Italy developed a unique Christian rite in the 7th and centuries. span style="font-variant:small-caps;text-transform:lowercase">VIII. The Benevento rite is more closely related to the liturgy of the Ambrosian rite than the Roman rite. The Benevento rite has not survived in that complete form, although most of the major festivals of local significance still exist. The Benevento rite seems to have been less comprehensive, less systematic, and more liturgically flexible than the Roman rite.

Characteristic of this rite was the Beneventan chant, a Lombard-influenced chant that bears similarities to the Ambrosian chant of Lombard Milan. Beneventan chant is broadly defined by its role in the liturgy of the rite; many Beneventan chants were assigned multiple roles when inserted into Gregorian chants, appearing variously as antiphons, offertories, and communions, for example. It was eventually supplanted by Gregorian chant in the 11th century.

The main center of Beneventan chant was Montecassino, one of the first and largest abbeys of Western monasticism. Gisulf II of Benevento donated a large part of land to Monte Cassino in 744 and it became the base of an important state, the Terra Sancti Benedicti , which was subject only to Rome. Montecassino's influence on Christianity in southern Italy was immense. Monte Cassino was also the starting point of another characteristic of Beneventan monasticism: the use of a distinctive Beneventan script, a clear, angular form of script derived from Roman cursive as used by the Lombards.

Art and architecture

During their nomadic phase, the Lombards created little art that could not be easily carried with them, such as weapons and jewelry. Although relatively little of these works has survived, they resemble those of the other Germanic tribes of northern and central Europe from the same period.

The first great modifications of the Germanic style of the Lombards occurred in Pannonia and especially in Italy, under the influence of the local Byzantine and early Christian styles. From pagan nomads they became sedentary Christians opening up to new forms of artistic expression, such as architecture (especially churches) and the decorative arts that accompany it (such as frescoes).

Few Lombard buildings have survived. Most of them have been lost, rebuilt, or renovated at some point, so they retain little of their original Lombard structure. Lombard architecture has been well studied in the 20th century, and Arthur Kingsley Porter's four volumes Lombard Architecture (1919) are a "monument of illustrated history."

The small Oratorio di Santa Maria in Valle in Cividale del Friuli is probably one of the oldest surviving pieces of Lombard architecture, as Cividale was the first Lombard city in Italy. Here are also the most outstanding pieces of Lombard sculpture, greatly influenced by the Byzantine style: the altar of King Rachis (740) and the saints.

Parts of Lombard constructions have been preserved in Pavia (San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro, Basilica of Santísimo Salvatore, Monastery of San Felice, Crypts of Sant'Eusebio and San Giovanni Domnarum) and Monza (cathedral). The Autarian Basilica at Fara Gera d'Adda near Bergamo and the church of San Salvatore in Brescia also have Lombard elements. All of these buildings are found in northern Italy (Langobardia major), however the best-preserved Lombard structure is found in southern Italy (Langobardia minor). It is about the church of Santa Sofia in Benevento; It was erected in 760 by Duke Arechis II. It preserves Lombard frescoes on the walls and even Lombard capitals on the columns.

Lombard architecture flourished thanks to the impetus given by Catholic monarchs such as Teodolinda, Liutprando and Desiderio, and the founding of monasteries to promote their political control. The Bobbio Abbey was founded at this time.

Some of the late Lombard structures of the IX and X contain the style elements associated with Romanesque architecture and have been called "early Romanesque". These buildings, along with other similar ones in the south of France and Catalonia, are considered to mark a transitional phase between the pre-Romanesque and the full Romanesque.

Like most Germanic peoples, the Lombards excelled in the applied arts, which is logical within a nomadic tradition in which fortune was invested not in the land, but in objects they could take with them, such as jewelry, clothing, or weapons. The Lombards received Scytho-Sarmatian influences, with features typical of steppe art that included the representation of fantastic animals, such as griffins; these themes passed to Gothic goldsmithing under the influence of the Lombards. Special mention should be made of the treasure of the cathedral of Monza, which is awarded to Queen Teodolinda and which includes the Iron Crown, which is said to have been made with a nail from the Cross of Christ.

Contenido relacionado

Wesley-clark

Bolivian Politics

Cliometrics