Linguistics

The linguistics (from the French linguistique; this from linguiste, «linguist» and that from the Latin "lingua", «language») is the scientific study of the origin, evolution and structure of language, in order to deduce the laws that govern languages (ancient and modern). Thus, linguistics studies the fundamental structures of human language, its variations across all language families (which it also identifies and classifies), and the conditions that make understanding and communication possible through natural language (this the latter is particularly true of the generativist approach).

Although grammar is an ancient study, the non-traditional approach to modern linguistics has several sources. One of the most important is the Neogrammatiker, who inaugurated historical linguistics and introduced the notion of law in the context of linguistics and, in particular, formulated various phonetic laws to represent linguistic change. Another important point is the terms synchrony, diachrony, and structuralist notions popularized by the work of Ferdinand de Saussure and the Cours de linguistique générale (inspired by his lectures). The century XX is considered, from the structuralism derived from the works of Saussure, the "starting point" of modern linguistics. At that time the use of the word "linguistics" seems to have become widespread. The word "linguist" is found for the first time on page 1 of volume I of the work Choix des poésies des troubadours, written in 1816 by Raynouard.

Target

The objective of theoretical linguistics is the construction of a general theory of the structure of natural languages and of the cognitive system that makes it possible, that is, the abstract mental representations that a speaker makes and that allow him to make use of language. language.

The objective is to describe the languages characterizing the tacit knowledge that the speakers have of them and to determine how they acquire them. There has been some discussion about whether linguistics should be considered a social science or rather part of psychology. In the social sciences the awareness of the participants is an essential part of the process; however, the consciousness of the speakers does not seem to play any relevant role in linguistic change or in the structure of languages. Although the speaker's consciousness certainly does have a role in areas normally included within linguistics, such as sociolinguistics or psycholinguistics, these two areas are not the main nucleus of theoretical linguistics, but disciplines that study collateral aspects of language use.

The aim of applied linguistics is the study of language acquisition and the application of the scientific study of language to a variety of basic tasks such as the development of improved methods of language teaching. There is considerable debate about whether linguistics is a social science, since only humans use languages, or a natural science because, although it is used by humans, the intention of the speakers does not play a significant role in evolution. history of languages since they use linguistic structures unconsciously. This was studied by F. de Saussure, who came to the conclusion that changes in a language are produced arbitrarily by involuntary variations made by the subject, and that the language varies throughout history. That is why he proposes that the study of the language must be carried out diachronically and synchronously. Consequently, Saussure puts aside the history of languages and studies them synchronously, at a given moment in time. In particular, Noam Chomsky points out that linguistics should be considered part of the realm of cognitive science or human psychology, since linguistics has more to do with the functioning of the human brain and its evolutionary development than with social organization or institutions., which are the object of study of the social sciences.

In order to situate the scope or objective of a linguistic investigation, the field can be divided in practice according to three important dichotomies:

- Theoretical linguistics for practical purposes, whose differences have been pointed out a little higher.

- Synchronous linguistics versus diachronic linguistics. A synchronous description of a language describes the language as it is at a given time; a diachronic description deals with the historical development of that language and the structural changes that have taken place in it. Although in its scientific beginnings the linguistics of the centuryXIX was first of all interested in linguistic change and the evolution of languages over time, the modern approach focuses on explaining how languages work at a given point in time and how speakers are able to understand and process them mentally.

- Microlinguistic versus macrolinguistic. The first refers to a more restricted view in the field of linguistics, and the second to a wider one. From a microlinguistic point of view, languages should be analysed for their own benefit and without reference to their social function, or the way they are acquired by children, or the psychological mechanisms that underlie the production and reception of speech, or the aesthetic or communicative function of language, etc. In contrast, macrolinguistics cover all these aspects of the language. Several areas of macrolinguistics have had a terminological recognition such as psycholinguistics, sociolinguistics, anthropological linguistics, dialectology, mathematical linguistics, computer linguistics and stylists.

History

Pre-scientific linguistics

The science that has been built around the facts of language has gone through three successive phases before adopting the current modern approach.

It began by organizing what was called the grammar. This study, inaugurated by the Greeks and continued especially by the French, was founded on logic and devoid of any scientific vision, and was not interested in language itself. What the grammar proposed was only to give rules to distinguish the correct forms from the incorrect forms; it was a normative discipline, far removed from pure observation, and his point of view was therefore necessarily narrow.

Then philology appeared. A philological school already existed in Alexandria, but this term is associated above all with the scientific movement created by Friedrich August Wolf, beginning in 1777, which continues to this day. Language is not the only object of philology, which wants above all to fix, interpret, and comment on texts. This first study also leads to literary history, customs, institutions, etc.; everywhere he uses his own method, which is criticism. If it deals with linguistic questions, it is above all to compare texts from different periods, to determine the particular language of each author, to decipher and explain inscriptions written in an archaic or obscure language. Undoubtedly, these investigations are those that prepared historical linguistics: Ritschl's works on Plautus can already be called linguistic, but, in this field, philological criticism fails on one point: that it clings too slavishly to the written language, and forgets the living language For the rest, Greco-Roman antiquity is the one that absorbs it almost entirely.

The third period began when it was discovered that languages could be compared with each other. This was the origin of comparative philology or comparative grammar. In 1816, in a work entitled System of Sanskrit Conjugation, Franz Bopp studied the relationships between Sanskrit and Germanic, Greek, Latin, etc. and he understood that the relations between parent languages could become a self-contained science. But this school, having had the indisputable merit of opening a new and fertile field, did not come to constitute the true linguistic science. He never bothered to determine the nature of his object of study. And without such an elementary operation, a science is incapable of procuring a method. (Excerpt from Chapter I "A Glance at the History of Linguistics" of the Introduction of the General Linguistics Course. Ferdinand de Saussure)

Scientific Linguistics

Modern linguistics began in the 19th century with the activities of those known as neogrammarians who, thanks to the discovery from Sanskrit, they were able to compare the languages and reconstruct a supposed original language, the Proto-Indo-European language. This encouraged linguists to create a positive science, even going so far as to speak of phonetic laws for language change.

It was not, however, until the publication of the General Linguistics Course (1916), made up of notes that students took in the course taught by the Swiss Ferdinand de Saussure, when linguistics became in a science integrated into a broader discipline, semiology, which in turn is part of social psychology, and define its object of study. The distinction between language (the system) and speech (use) and the definition of the linguistic sign (meaning and signifier) have been fundamental for the subsequent development of the new science. However, his perspective —known as structuralist and which we can describe, in opposition to later currents, as empiricist— will be called into question at the moment when it had already given most of its fruits. and, therefore, its limitations were more highlighted.

American Structuralist Approach

After the outbreak of the First World War, the lack of communication between continents made collaborative linguistic work impossible and in line with the same objectives. American linguists and anthropologists then decided to focus on the linguistic reality of the local non-literate aboriginal communities, whose languages were disappearing. Thus, experts such as Bloomfield, Boas or Sapir tried to redefine the approach to language Archived September 18, 2020 at the Wayback Machine, oriented towards its relationship with the world; they called this "linguistic relativism.

Latest Approaches

In the XX century, the American linguist Noam Chomsky created the current known as generativism. With the idea of solving the explanatory limitations of the structuralist perspective, there was a shift in the focus of attention that went from being language as a system (the Saussurian langue) to language as a process of the mind of the user. speaker, the innate (genetic) ability to acquire and use a language, competence. Any proposal for a linguistic model must, then —according to the generativist school— be adapted to the global problem of the study of the human mind, which leads to always seeking mental realism in what is proposed; that is why generativism has been described as a mentalist or rationalist school. In this perspective linguistics is considered as a part of psychology or more exactly cognitive science.

Both the Chomskian and the Saussurean schools have as their objective the description and explanation of language as an autonomous, isolated system. Thus they collide —both equally— with a school that gained strength at the end of the XX century and is known as functionalist. In opposition to it, the traditional Chomskian and Saussurian schools are jointly called formalists. Functionalist authors —some of whom come from anthropology or sociology— consider that language cannot be studied autonomously, ruling out the "use" of language. The most relevant figure within this trend is perhaps the Dutch linguist Simon C. Dik, author of the book Functional Grammar. This functionalist position brings linguistics closer to the social realm, giving importance to pragmatics, change and linguistic variation.

The generativist and functionalist schools have shaped the panorama of current linguistics: practically all currents of contemporary linguistics stem from them and their mixtures. Both generativism and functionalism seek to explain the nature of language, not just the description of linguistic structures.

Study levels

We can approach the study of language at its different levels, on the one hand, as a system, attending to the rules that configure it as a linguistic code, that is, what is traditionally known as grammar and, on the other hand, as an instrument for communicative interaction, from disciplines such as pragmatics and textual linguistics.

From the point of view of language as a system, the levels of linguistic inquiry and formalization that are conventionally distinguished are:

- phonetic level, which includes:

- Phonetics: study of the phonemes of a tongue.

- Phonology: study of the individual allophonic realization of such phonemes. Fons are sounds of speech, differentiated realizations of the same motto.

- Although they are not strictly linguistic fields, as cultural and historical factors are involved, the study of Graphémica, Orthology and Orthography is often considered within this level.

- Morphos-incidence level, including:

- Morphology: study of the minimum unity with meaning (the morphema), the word and the mechanisms of formation and creation of words.

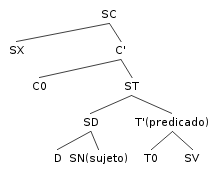

- Syntax: study of the syntagmatic combination, on two levels: the suborational, which corresponds to the so-called syntagmas, and the orational that studies the specific syntagmatic relationships of the linguistic signs that make up, in turn, the upper grammatical linguistic sign of the system of the tongue.

- Lexicon level, including:

- Lexicology: study of the words of a language, its organization and its meanings.

- Lexicograph: deals with the theoretical principles underlying the composition of dictionaries.

- Phraseology: study of repeated speech phrases (locutions, routine formulas, placements) of a language, its organization and its meanings.

- Paremiology: study of the paremias (refranes and proverbs) of a language, its organization and its meanings.

- Semantic level, which, although not properly a level, since it affects everyone, except the phonetic-phonological (actually the phenological does have semantic content; see "minimum pairs") includes:

- Semantics: study of the meaning of linguistic signs.

From the point of view of speech, as an action, it stands out:

- Text: superior communication unit.

- Pragmatic: studies the statement and the statement, the deixis, the modalities, the acts of speech, the presupposition, the information structure of the statement, the analysis of discourse, the dialogue and the textual language.

Depending on the approach, the method and components of analysis vary, which are different, for example, for the generativist school and for the functionalist school; therefore not all of these components are studied by both currents, but rather one focuses on some of them, and the other on others. The theoretical study of language is in charge of General Linguistics or Theory of Linguistics, which deals with research methods and issues common to various languages.

Language schools

The type of problem considered central and most important in each stage of the study of modern linguistics has been changing from historical linguistics (born from studies of etymologies and comparative philology) to the study of syntactic structure, passing by dialectology, sociolinguistics. The following list lists some of the top schools in chronological order of appearance:

- Neograms (s. XIX)

- Structuralism (first half s. XX)

- Prague Language Circle

- Copenhagen or Glossary School

- American linguistic structure (Franz Boas, Edward Sapir, B.L. Whorf)

- Language structure (Leonard Bloomfield, Bernard Bloch, Zellig Harris, Charles F. Hockett)

- Distribution

- Tagmémica (K. L. Pike, R. E. Longacre)

- Stratifying grammar (Sydney Lamb)

- Transformative Generative Grammar (Noam Chomsky) (second half s. XX)

- Principles and parameters (years 1980)

- Recruitment and ligation (1980s)

- Minimist program (1990-present)

- Functional systemic grammar (Michael Halliday)

- Language function (André Martinet) (second half s. XX-present)

- Theory of Optimism (1993-present)

Humanistic Linguistics

The fundamental principle of humanistic linguistics is that language is an invention created by people. A semiotic tradition of linguistic research views language as a system of signs arising from the interplay of meaning and form. The organization of linguistic levels is considered computational. Linguistics is seen as essentially related to social and cultural studies because different languages are shaped in social interaction by the speech community. Frameworks that represent the humanist view of language include structural linguistics, among others.

Structural analysis means dissecting each linguistic level: phonetic, morphological, syntactic and discursive, down to the smallest units. These are collected in inventories (for example, phonemes, morphemes, lexical classes, phrase types) to study their interconnection within a hierarchy of structures and layers. Functional analysis adds to structural analysis the assignment of semantic roles and other functional roles. that each unit can have. For example, a noun phrase can function as the subject or object of the sentence; or the agent or the patient..

Functional linguistics, or functional grammar, is a branch of structural linguistics. In the humanist reference, the terms structuralism and functionalism are related to their meaning in other human sciences. The difference between formal and functional structuralism lies in the way the two approaches explain why languages have the properties they do. The functional explanation involves the idea that language is a tool for communication, or that communication is the main function of language. Consequently, linguistic forms are explained by appealing to their functional value or utility. Other structuralist approaches take the view that form derives from the internal mechanisms of the multilayered, bilateral language system.

Biological Linguistics

Approaches such as cognitive linguistics and generative grammar study linguistic cognition with a view to discovering the biological foundations of language. In generative grammar, these foundations are understood to include innate domain-specific grammatical knowledge. Therefore, one of the central concerns of the approach is to discover which aspects of linguistic knowledge are innate and which are not.

Cognitive Linguistics, by contrast, rejects the notion of innate grammar and studies how the human mind creates linguistic constructs from event schemata, and the impact of cognitive limitations and biases on human language. Similar to NLP, language is approached through the senses. Cognitive linguists study the embodiment of knowledge by looking for expressions that relate to modal schemata.

A closely related approach is evolutionary linguistics, which includes the study of linguistic units as cultural replicators. It is possible to study how language replicates and adapts to the mind of the individual or the speech community. Construction grammar is a framework that applies the concept of meme to the study of syntax.

The generative approach versus the evolutionary approach are sometimes referred to as formalism and functionalism, respectively. However, this reference is different from the use of the terms in the human sciences.

Interdisciplinary Studies in Linguistics

- Language acquisition

- Linguistic anthropology

- Criptoanalysis

- Description

- Scripture

- Stylist

- Philosophy of language

- Anthropological linguistics

- Applied language

- Cuantitative linguistics

- Computational language

- Linguistics of corpus

- Evolutionary Linguistic

- Forensics

- Historical or comparative language

- Neurolinguistic

- Pragmatic

- Psycholinguistic

- Sociolinguistic

- Use of language

Linguistic study topics

- Individual speakers, universal speaking and linguistic communities

- Description and prescription

- Language spoken or written

- Diacrony and synchrony

Language Research Centers

- CELIA Centre d'Études des Langues Indigènes d'Amérique

- CUSC - Centre Universitari de Sociolingüística i Comunicació, Universitat de Barcelona, http://www.ub.edu/cusc

- PROEL Promotora Española de lengua

- SIL Summer Institute of Linguistics

- CLiC-Centre de Llenguatge i Computació, Universitat de Barcelona

- Valparaiso Language School

- Child Language and Literacy Lab

- National Institute of Indigenous Languages, Government of Mexico.

Featured Linguists

- Willem Adelaar

- John L. Austin

- Charles Bally

- Andrés Bello

- Émile Benveniste

- Leonard Bloomfield

- Franz Bopp

- Ignatius

- Salvador Gutiérrez Ordóñez

- Francisco Marcos Marín

- Pedro Martín Butragueño

- Lyle Campbell

- Rodolfo Cerrón Palomino

- Eugen Coșeriu

- Noam Chomsky

- Violeta Demonte

- Lucien Tesnière

- Robert M. W. Dixon

- John Rupert Firth

- Joseph Greenberg

- Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm

- Claude Hagège

- Michael Halliday

- Henk Haverkate

- Louis Hjelmslev

- Roman Jakobson

- William Labov

- George Lakoff

- Čestmír Loukotka

- André Martinet

- Alfredo Matus Olivier

- Igor Mel'čuk

- José G. Moreno de Alba

- Merritt Ruhlen

- Edward Sapir

- Ferdinand de Saussure

- Sergéi Stárostin

- John Sinclair

- Morris Swadesh

- Alfredo Torero

- Nikolái Trubetskói

- Robert van Valin

- Concepción Company

- Teun van Dijk

- Viktor Vinográdov

Languages of the world

About 6000 languages are known, although the number of languages currently spoken is difficult to determine due to several factors:

- First, there is no universal criterion to decide whether two speak with a certain degree of mutual intelligibility should be considered dialects of the same historical language or two different languages.

- Secondly, there are insufficiently studied areas of the planet to specify whether human groups present in them actually speak the same or the same languages as other more known human groups. This applies especially to New Guinea; certain areas of the Amazon, where there is evidence of more than 40 uncontacted tribes; the southeast of Tibet, western Nepal and northern Burma and one of the Andaman Islands.

- Thirdly, as long as speakers are discovered of some language that was presumed extinct, and that they are able to use it in their daily lives.

Despite the high number of mutually unintelligible languages, historical linguistics has been able to establish that all these languages can be grouped into a much smaller number of language families, since each of these languages derives from a protolanguage or language mother of the family This fact usually serves as the basis for the phylogenetic classification of the world's languages. In addition to this type of classification, various types of typological classification can also be made, referring to the type of structures present in a language rather than its historical origin or its relationship with other languages.

List of families and languages of the world

- List of languages: languages of the world organized by alphabetical order.

- Families of languages: phylogenetic classification of languages, according to their genetic relationship and historical origin.

- Annex: National language classes: list by alphabetical order of different countries in which the description of various languages spoken in each country is accessible.

- ISO 639: codes for languages and groups or families of languages.

Geographic distribution

The distribution of languages across continents is very uneven. Asia and Africa have about 1,900 languages each, this represents 32% of the total linguistic diversity of the planet. On the contrary, Europe has only 3% of the languages on the planet, being the continent with the least linguistic diversity. In America there are about 900 indigenous languages (15% of the planet's languages) and in Oceania and adjacent regions about 1,100 (18%).

The most linguistically diverse region on the planet is New Guinea and the least diverse is Europe. In the first region until the XX century there was no state entity, while in Europe the existence of large states since ancient times, it restricted cultural diversity, producing a very important standardizing effect in terms of linguistic diversity.

Languages by number of speakers

The world's languages are highly dispersed in terms of the number of speakers. In fact, a few major languages concentrate the majority of speakers of the world population. Thus, the 20 most widely spoken languages, which account for around 0.3% of the world's languages, concentrate almost 50% of the world's population, in number of speakers; while the 10% of the least-spoken languages barely concentrate 0.10% of the world's population. And although the average number of speakers of a terrestrial language is around one million, 95.2% of the world's languages have fewer than one million speakers. This means that the most widely spoken languages accumulate a disproportionately high number of speakers and for this reason the previous average is misleading regarding the distribution. Languages with few speakers may be in danger of extinction, although not necessarily, since the key factor for the disappearance of a language is usually the presence of language substitution.

Contenido relacionado

Annex: Lexical differences between Spanish-speaking countries

Accusative case

Lexical accent