Lima culture

Geographic location of the Lima culture

The Lima culture developed fundamentally in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín rivers, located on the central coast of Peru. These three valleys (including the Dry Ancón Valley) have common characters that give them geographical unit.

Potra

A distinctive seal of this culture is its iconography, which is simple: most of its designs are based on the image of two snakes with triangular heads (whose bodies form a zigzag), a smiling supernatural being and an octopus of the Species Octopus sp . This iconography had to be created by weavers and then copied to other materials and supports.

Some peculiar characteristics of the Lima culture are:

- The construction techniques, basically two:

- The use of the upholstery, that is to say, of walls made with large adobes or adobones of clay.

- The use of small adobes shaped as a parallelepiped, these arranged in the walls as books in a shelf.

- The design of monumental architectural complexes, structured around squares and an adjacent housing area.

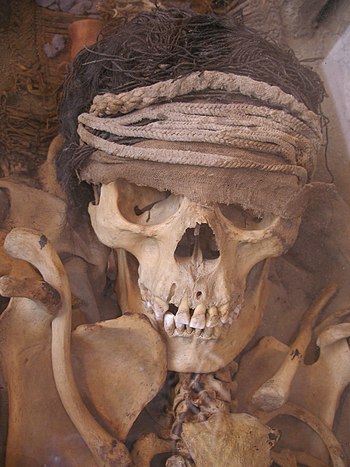

- Funeral customs (they buried the bodies in an extended way, of dorsal or ventral cubit, a fact that abruptly broke the old tradition of the bodies with a reflected position).

Main settlements

The main sites of the Lima culture are:

- In the valley of Chancay: Cerro Trinidad.

- In the dry valley of Ancón: Playa Grande.

- In the Chillón valley: Cerro Culebra, La Uva, Copacabana.

- In the Rímac valley: Maranga, which is an immense architectural complex, the most important of the last phases of the lime culture, currently in the districts of the Near, San Miguel and Pueblo Libre, where stands out the huaca of San Marcos; the Cajamarquilla complex and the pyramid of Nieveria, both in the district of Lurigancho-Chosica; Pucigancho, in the district of San Juan Lur Pugliana or Juliana, in the coastal zone of the district of Miraflores; the Trujillo huaca (Huachipa); Vista Alegre (near Puruchuco).

- In the Lurin valley: the old temple of Pachacámac, that is the oldest construction of this sanctuary.

PERIODS OF YOUR DEVELOPMENT

<pThree big stages

When the Chavín culture decay, the communities of the central coast of the current Peru developed in three stages until they were absorbed by the Huari culture. These stages differ mainly from the style of their respective ceramics and are called:

- First stage: Bathrooms of Boza or Miramar (Culture pre Lima, century)III a. C. al II d.C.)

- Ceramics: White on Red

- Second stage: Playa Grande (Culture lime, century)II Al VI (d)

- Tricolor ceramic: White, red and black

- Style interlocking

- Third stage: Maranga - Cajamarquilla - Nievería (Culture lime, century)VI Al VII (d)

- Tetracolor ceramic: White, red, black and grey

The subdivision in phases by T. Patterson

These styles were in turn subdivided into a classification that the American archaeologist Thomas C. Patterson made in 1964. This scholar, following the methodological contributions of John Rowe, defined 13 groups of ceramic sets that share a significant number of features and correspond to the same number of phases:

- The first four phases are the antecedent of lime culture, so it is also called as pre Lima, and is characterized by the development of the style White on Red, whose ceramic samples were found in Miramar, near Ancón, which have been correlated with other similar style samples found in Baños de Boza and Cerro Trinidad, in the valley of Chancay.

- The next nine phases or styles correspond to the lime culture; the first seven of them correspond to the style known as interlocking and the last two to Maranga.

Ceramic styles

Below is a brief explanation of the three great styles of pre Lima and Lima ceramics:

- The white style on red [pre lime] is characterized by its white painted decoration on the natural red background of the vessel (another modality was to cover first the surface of the vessel with a white paint on which it was decorated with black and red strokes). The ceramic specimens are burdo-like, with simple and geometric decoration. The most common forms are almost globulre pots with short neck, plates, bowls, small pitchers, etc.

- The style interlocking (interlaced) [lima] is characterized by having as the main reason of decoration a series of stylized figures in the form of fish or serpent intertwined among themselves, as geometric figures of lines and points. Use the white, red and black (tricolor) colors on a red goose background. The representative forms are cups, pots and glasses.

- The style Maranga [lima] is characterised by presenting in its decor of grecas, interlaced fish, interlocking lines, triangles, circles and white dots. Use the red, white, black and gray (tetracolor) colors on a orange, fine, lustrous and shiny background. The forms of the ceramios are very varied, including the so-called lenticular form. Its final phase is known by the name of style Nievera.

Stages

The stages of cultural development of this culture are:

First stage: BOZA OR MIRAMAR BATIES

As already noted, this cultural stage is the immediate antecedent of the Lima culture and is located in the end of the Chavín influence and the beginnings of the early intermediate (century III </s, because they seem to have foreign origin. We even know at the time of the transition, the white style on Red coexisted for a good time with that of the Lima culture.

The German archaeologist Max Uhle was the one who at the beginning of the century XX </s Trinidad, near the town of Chancay. He also found evidence of another ceramic style, which would later be baptized interlocking, whom he missed as the oldest. For the 1920s Alfred Kroeber continued the studies in Cerro Trinidad, and later, William D. Strong and John M. Corbett found remains of white style ceramics on red in Pachacámac, further south, in the Lurin Valley.

It was Gordon Willey who was responsible for correctly fixing the chronological sequence of the ceramic styles found in Cerro Trinidad, placing in the white style on red as the oldest of that part of the central coast. Willey also excavated in Baza Baños, also located in the Chancay Valley, which turned out to be an isolated place with almost exclusive occupation of the white style on red, which is why it was known as "Baza de Boza style." Willey published the results of his studies in 1945.

Other excavations made in Miramar (near Ancón) brought to light various pottery specimens with another modality of white style on red, which was baptized as "Miramar style." In 1964 the American archaeologist Thomas Patterson, in his well -known sequence of phases of ceramic development, placed in the white style about red or miramar in four phases, prior to those of the Lima culture.

The white style on red, in its modalities Baza and Miramar bathroom Rímac and Lurín), after the cessation of the influence of Chavín style ceramics. The excavations have brought to light remains of almost global pots, with a short neck, of dilated and almost convex opening. Dishes, glasses, small pitchers, etc.

of this stage small fishing villages (Ancón) and farmers are known. The latter occupied terrified hills at the edge of the valley. The side ravines were particularly important because they collected water during the rainy season. A reservoir system in Huachipa allowed to store water. In Tablada de Lurín, extensive cemeteries have been found, from 20 to 50 hectares, which housed thousands of burials of this era. The presence of weapons, cheerleaders and funeral offerings and the evidence of shelters protected from walls in the high parts of the hills indicate that relations with neighboring ethnic groups were not entirely peaceful.

Second stage: Playa Grande

This stage and its ceramic style (also called interlocking ) correspond to the first stage of the Lima Culture (centuries II to V d. C.).

What gives him his name is the settlement of Playa Grande located in the current spa of Santa Rosa, district of Santa Rosa, Metropolitan Lima, 3 km south of Ancón, discovered by Louis Stumer In 1952. However, the style had already been previously identified by Max Uhle in Cerro Trinidad (Chancay), and studied by Kroeber (1926), Strong and Corbett (1943) and Willey (1943), under the name of interlocking or Interlocked Fish , in view of the fact that its main characteristic is a stylized design of fish (or snakes) intertwined that decorate the walls of the ceramics, combining the colors black, white and red (white and red (white and red (tricolor). Apparently, its origin would be in the influence of the recovery culture, located further north, in Áncash.

His stratigraphic position as after Boza Baños and before Maranga and Tiahuanaco-Huari was corroborated by thorough studies conducted by Ernesto Tabío in 1957. Then, Patterson included it in his sequence of ceramic development that encompassed under the name of “ Lima ”(1964).

demonstrating technological progress, potters at the service of ceremonial centers of this era manufactured fine ceramic and pleasant ways, although large, thick pasta and gross -looking tested have also been found.

The distribution area of this style is between the Chancay Valley to the north, and that of Lurín to the south. To the east, perhaps it reached the cisandino segment. All of which suggests that the great lords of the central coast had expanded their domains.

Buildings made during the Boza-Miramar bathroom phase were expanded, becoming large staggered platform pyramids. These palaces-time had huge courtyards for ritual meetings and commercial activities. Urban complexes were also built in various places of the valleys. The sanctuaries and homes of the nobles were surrounded by extensive plantations and pens with abundant cattle.

The quadrangular base of monumental architecture was made with stone walls. Then the platforms of several floors appeared, built with adobitos in different shape and size. The inner walls were plastered tapia. They decorated their walls with red and white nuances, which made them see how splendid buildings. Some main walls were decorated with the interlocking style, multicolored, as has been discovered in Cerro Culebras (Chillón Valley).

To make these gigantic pyramids, with thousands of stones and millions of adobites, the participation of architects, masons, assistants, carriers, painters, decorators, carpenters, technicians and abundant labor must have been necessary. Therefore, it follows that the population of the valleys must have been very numerous.

A significant characteristic of this stage were the changes in funeral behaviors: the traditional flexed position of the body with the members strongly shrunk, sitting or on one side, is replaced by the Lima ritual, with the extended position of the body. Scarce dates obtained from carbon 14 would place this fact between the century iv and the century v d. C. In Playa Grande, 12 burials were located with 30 individuals; The most notable thing they had quartz offerings, jadeita, turquoise, lapislázuli, spondylus and obsidian. In one of the tombs two human heads were found as offering, as well as birds of beautiful plumage.

Of all the settlements of this era, Playa Grande was probably the most important, then being well above the old sanctuary of Pachacámac and other settlements of the Lima culture. The location of Playa Grande, in front of the sea and a group of islands show their religious importance, as well as the wealth of its ceramics and instruments found (for example, the Lanzón de Playa Grande).

Unfortunately, much of the information hidden in Playa Grande was destroyed with the construction of the spa; At present and due to lack of resources and interest of the authorities, underlying remains can be lost in more than 100 hectares of the non -urbanized area of the spa; Zone on which several real estate companies have put their interest with consent from the state entity.

Other classic examples of the Playa Grande style were found in the Chillón Valley, particularly in Cerro Culebra and Copacabana, two settlements with monumental architecture. Also, extremely comparable vessels and textiles, associated with architecture with adobitos, were also found in the neighboring basins of Rímac (Huaca Trujillo, near Cajamarquilla, in Huachipa) and Lurín (Pachacámac and La Tablada de Lurín).

Third Stage: Maranga - Cajamarquilla - Nievería

The last period in the history of the Lima culture (VI-VII centuries d. C.) was rebuilt by archaeologists primarily from the excavations in the valleys of Rímac and Lurín. Crucial importance had the work in Cajamarquilla and Nievería (both on the right bank of the Rímac) as well as in the monumental complex of Pyramids of Maranga (left bank of the same river), today partially within the university city of the University of San Marcos.

Max Uhle was the first to study the ceramic style of Nievería, of fine finish and elegant decoration, which related to other samples found in Cerro Trinidad and which he called "Proto Lima", believing her of Nasca origin. Raoul Dancourt, in 1922, preferred to call Cajamarquilla for the ceramics of Nievería. Subsequently, in 1949, the Ecuadorian archaeologist Jacinto Jijón and Caamaño used the term "Maranga" for the late phase of the so -called "Proto Lima", by the name of the architectural complex where he then studied. It was Stumer who suggested the names of "Playa Grande" for the early stages (then called interlocking ) and "Maranga" for late. And in 1964, T. Patterson unified these names under the word "Lima", divided into 9 phases, placing the Nieverría style at the beginning of the average horizon (660 d. C.). It is currently defined as a local and contemporary variety of the last phase of the Lima or Maranga style.

Maranga style could be a derivation of Playa Grande; The truth is that it surpasses it technically. The potters of this period made ceramics in various forms, decorated with greezes, intertwined fish, cross -linked lines, triangles, circles and white points. As for the coloration, it was Tetracolor: in addition to the colors already used in the posterior phases of Playa Grande (red, white and black) a new color, the gray was added. This ceramic style lasted until the domination of the Huaris, no doubt because it was superior to that of the conquerors, although it inevitably suffered the foreign influence.

It was in the final period of this stage, after a phenomenon of the child that occurred between the 5th and VII centuries. C. when intense agricultural activity resumed in the Huachipa creek. The settlements moved from the easy places to defend (elevations or hills) to the spaces adjacent to the cultivation fields. All this motivated the rise of the great pyramidal constructions and their surrounding buildings and enclosures, being the most spectacular in terms of size and extension of the Cajamarquilla site. The other notable complex is that of Maranga.

These pyramids (which would be palaces-Santuarios) in their structure followed the guidelines of other facts in the previous stage, but were complemented with some details. They are monumental architectural works, full of platforms and palace, all painted yellow and white (the red of the previous stage was discarded). In a good extension of these sanctuaries, gigantic murals were painted, mainly with fish figures. Those polychrome walls could be seen from afar.

In addition to the already mentioned complexes of Maranga and Cajamarquilla-Nievería, there are other architectural testimonies belonging to this stage:

- In the lower valley of the Rimac (current province of Lima): Armatambo, at the foot of the Solar Moor (Chorrillos); and Mangomarca (San Juan de Lurigancho), both currently affected by urban expansion. Other relatively cotaneous architectural testimonies are the Pucllana huaca (Miraflores) and the Granados huaca (La Molina).

- In the Chillón valley the structures of Carabayllo and the huaca of Cerro Culebras stand out.

- In the dry valley of Ancón: the settlement of Playa Grande.

- In the valley of Chancay: the temple-palacio of Cerro Trinidad, where a polychrome mural was found, with interwoven fish design.

- In the Lurín valley: the old temple of Pachacámac adobitos.

The ability to mobilize entire communities for public works and a certain standardization in the style of ceremonial ceramics are indications of the existence of a central political power.

Artistic manifestations

Architecture

The monumental complexes are typical of the Lima culture: high pyramids with plazas and adjacent residential areas, accessible at their tops by means of paths bordered by walls and ramps.

Lima's monumental architecture has two recurring techniques:

- The use of the upholstery, i.e., walls made from large adobes or adobones of clay.

- The use of small bricks of adobes with a parallelepipe shape, which replaced the plane-convex adobe (paniforme) handmade. Very often these adobits are arranged inside the wall vertically, as books in a shelf. This technique did not survive after the end of lime culture.

A representative example of this architecture is the immense architectural complex of Maranga, today located within the urban area of Lima, between the districts of Cercado, Pueblo Libre and San Miguel. They are pyramidal monuments, with ramps and steps, enclosures and warehouses. One of the most notable buildings belonging to this group is the Huaca de San Marcos, located on Avenida Venezuela, on the campus of the University of San Marcos.

La Huaca Pucllana, in the district of Miraflores, is another construction characterized by the use of adobitos. It is a pyramidal construction accompanied by a series of structures formed by straight walls that form enclosures and patios, also built in adobitos.

Ceramics

The development of Lima ceramics is divided into two major stages:

- The "interlocking style" or "Playa Grande", which is characterized by having as the main reason for decoration a series of fish-shaped figures or intertwined snakes, as geometric figures of lines and points. Hence the name of interlocking that translated from English means “worked” or “interlinked”. It combines black, white and red (tricolor) colors on a red goose background. Ceramics are fine and in pleasant forms, although they have naturally also found large pots, thick pasta and gross appearance. The fine vessels found are spherical olives, cylindrical vessels, cups in chalice, camping vessels, plates and bowls of soft coverage, mamiform vessels or in the shape of a turtle.

- The style Marangawhich exhibits a more frequent use of modeling. His last phase is traditionally known as Nievera stylealready under the influence of Moche and Huari. Highlights the use of very fine clays as well as excellent cooking and surface finishing conditions. In its decoration it is characterized by grecas, intertwined fish, intertwined lines, triangles, circles and white dots. Use the red, white, black and gray colors (tetracolor) on a orange, fine, lusty and shiny background. The forms of the ceramios are very varied: there are lenticular vessels that, with strangulation in its central part, appear two mushroom dishes joined by their bases. They have asa-puente, sometimes uniting two long and conical hats or a gollete with the modeling of a anthropomorphic or zoomorpha figure or statuette (sculatory ceramic), or simply between the beak and the body of the vessel, which in these cases is spherical. There have also been dishes, pots and fine-finished clay pitchers, mostly.

As we have already pointed out, in 1964 Patterson subdivided this ceramic development of the Lima culture into nine styles, the first seven corresponding to the interlocking style and the last two to the Maranga style:

- La Lima 1 it was characterized by producing large pitchers and dishes, with black and white decoration.

- La Lima phase 2 ollas with straight neck and plates are found, and the first ones are applied a white or red gum on the surface.

- La Lima 3, where the glasses of straight sides predominate, large pitchers, dishes, etc.

- La Lima 4, in which a new type of pot with flat edge appears, with painted decoration.

- La Lima 5 where the dishes of curved sides, flat edge pots and mamiform pitchers are presented mainly and the recurring motif is the interlocking snake.

- La Lima phase 6, in which large pitchers predominate.

- La Lima phase 7 it has curved-necked pots and expanded-necked pitchers, among others, with decoration of triangles and painted intertwined snakes.

- La Lima 8, in which previous forms are repeated, with decoration of triangles, broad bands of colors and thin white lines painted.

- La Lima phase 9which repeats previous forms and finds the snake intertwined in the decoration.

Textile Art

Textiles were another important activity of the Limas. Cotton fibers and camelid wool were widely used. The prevailing decorations are the same as ceramics: figures of fish, snakes and various intertwined lines. A greater number of colors are used in the Maranga era compared to pottery. Blue, gray, green, brown and various shades of red appear. At that time, upholstery also appeared (for the first time on the central coast), and brocade and painting on fabric.

Feather art

Feather art was one of the characteristic artistic activities of the Limas. It consisted of fixing feathers painted or selected in different colors (red, green, black, blue and yellow), they were sewn within a design scheme that gives the cloak an extraordinary beauty. The feathers are mainly from seabirds, parrots, macaws and other species from the inter-Andean valleys, obtained from interregional trade. These feathered fabrics were for the exclusive use of the lords in charge of the cult or the government.

Basketry

Another artistic activity with a remarkably developed technique was basketry. The archaeologist Ernesto Tabío, who carried out excavations in Playa Grande, has pointed out that this "was a remarkably basket-making town" (1955). Indeed, he found an extraordinary number of baskets, with great variety in their construction techniques, decoration motifs, size and shapes.

Economy

Like all coastal zone cultures, the base of their economy was fishing and agriculture.

Fishing

As in all coastal culture, fishing was a fundamental activity. The most curious thing is that, in addition to the artisanal fishing species (pejerrey, corvina, cojinoba, liza, etc.) fish remains have also been found that can only be found in schools that are 100 or 200 m deep, such as for example, the machete, the sardine, the anchoveta and the bonito. It is unknown how they managed to capture them.

They were great divers, that's for sure. They took sea shells up to 8 m deep, which served as decorative objects. In all the palaces they have been found in great quantity.

Agriculture

Agriculture became an intense activity. They gained farmland through a network of canals or aqueducts, some of which are still in use. Their main crops were: corn, pallar, beans, squash, pumpkin, sweet potato, peanuts, cherimoya, lucuma, pacae, etc. Such would be the fertility of the coastal valleys and the number of farms or cultivated spaces, that it is estimated that the Rimac Valley alone would accommodate a population of 200,000 people. Spanish chroniclers have testified that, in effect, said valley was the richest in ruins and remains of ancient constructions, particularly in the lower region, near the sea. The choice of Francisco Pizarro to found the capital of his government there, today the capital of the Peruvian Republic, was based on a pre-existing, prosperous and highly populated settlement. For this reason, we can affirm that the city of Lima was not actually born in 1535, the year of its Spanish foundation, but that its antecedents go back many centuries.

To ensure the permanent irrigation of their crop fields and the water supply for the populations, the “limas” built two monumental hydraulic engineering works in the Rímac valley that are still in use today:

- The river Surco, which is a irrigation channel that carries the waters of the river Rimac of Ate to Chorrillos, passing through Santiago de Surco, Miraflores and Barranco.

- The Huatica canal, which transports the waters from La Victoria to Maranga.

These works were carried out in the last period, the so -called Maranga, between 500 and 700 d. C. It is possible that the droughts of the century vi and the increase in rainfall caused by a phenomenon of the child during the century VII have been decisive stimuli for such works.

Commerce

During the time of splendor of the Lima culture, the entire area he occupied had undoubtedly become a large shopping center. His valleys connected it to strategic places in the Sierra, whose inhabitants exchanged their products. In archaeological sites there are still elements of neighboring regions and cultures, which naturally exerted influences on the artistic manifestations of the Limas, as Luis Lumbreras points out: “Lima culture is not an impersonal culture; To explain it, it has to resort to its relations with many other cultures of the coast and the Sierra, being its character of a strong receptivity. ”( of the peoples, cultures and arts of ancient Peru >. Lima, 1969).

Burials

Two forms of burials have been found:

- Common: The body was covered with one or two mants, accompanied by few household utensils, placed in horizontal position and buried at 1 m or 1.5 m depth.

- Special: The body was placed on a parihuela (liter size or portable bed) made of sticks and rods. The position of the deceased varies according to the time: for the stage before Lima, i.e. the so-called Boza Baths (“White on Red”), the position is lateral; for the next stage or Playa Grande (“interlocking”), the body is placed with ventral cubit (downsided) with the stretcher on the back; and for the final stage or Maranga, it is placed with a number of homework,

End of a culture

All excavated Lima constructions indicate that they were abandoned during the VIII d. C. It was theorized that the causes have been natural cataclys or foreign destructive invasions, such as that of the Huaris. However, the vestiges indicate that it was an organized closure of public spaces with full respect for precise rules. The courtyards and other constructions at the top of the pyramids were buried with intentional fillings. The accesses were sealed with adobe pircas, Greden or Stone blocks. We do not know if all cases of closing and abandonment occurred at the same time and for the same reasons. It is eventually possible that it was a ritual related to the death of the last residents of each palace of the Maranga phase. In any case, burials and other evidence of human activity show that the public architecture of Lima was abandoned when vessels and textiles adorned with designs from Tiwanacu and Nasca (Viñaque, Pachacámac and Atarco) were disseminated on the central coast). Sometimes, local potters also adopted those expressions (Nievería style).

This panorama of collapse of the central power contrasts with the dissemination of the local style, Nievería, towards Lambayeque, along with other southern styles. It is likely that several representatives of the Lima elites join other Huari groups and participate in the northern conquest. Already by then the Sanctuary of Pachacámac was reaching importance as a center of attraction of thousands of pilgrims, from where the worship of the God of the same name was spread in the Andean world. Perhaps it was in that center where the hypothetical alliance between Mr. Lima and the Huari was sealed.

Contenido relacionado

54

51

Carmona