Ligurians

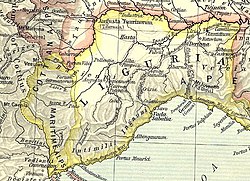

The Ligurians (Latin Ligures < *Liguses) were a protohistoric people of southern Europe. They inhabited the Italian region of Liguria in the Italian northwest and the French southeast in Nice (also in the Italian geographical area) that corresponds to the old Liguria between the Var and Magra rivers. Probably rooted in the Neolithic cultural complex of the western Mediterranean, it is not yet clear whether it is a pre-Indo-European or non-Indo-European people. Supposed traces of their language remain in toponymy and archaeology.

Ethnonym

According to Plutarch, they called themselves Ambrōnes, which would mean "people of the water" (like another people from northern Europe). The word Ligurian is probably of Greek origin. Some historians of the 20th century have considered in this term, the transposition of the name of an Anatolian town. Nino Lamboglia has hypothesized the existence of an indigenous root *liga, whose meaning is "marsh, swamp". Camille Jullian, Pascal Arnaud and Dominique Garcia have suggested that the word comes from the Greek lygies, meaning "very high, perched site". Ligures would then mean "those above".

History

Origins

The region inhabited by the Ligurians was introduced to agriculture and navigation through the Cardial-Impressed Ceramic culture that spread in the 6th and 5th millennia BCE. C. by the western Mediterranean. If we consider the Ligurians as a pre-Indo-European people, in the IV millennium BC. C. his ancestors participated in the rich cultural complex Chassey-Cortaillod-La Lagozza, which for a time united culturally south-eastern France, western Switzerland and[citation needed] northern Italy, to later divide again into smaller groups. The Indo-European invasions of the 13th century a. C. they conquered part of their territory, isolating the Ligurians in the subalpine region (current County of Nice and Liguria). Later they were romanized.

The Ligurians in ancient sources

A fragment of a text from the Catalogues of Hesiod (8th century B.C..), cited by Strabo, mentions the Ligurians among the three great groups of barbarian peoples, along with the Ethiopians and the Scythians.

The most common interpretation of this text is that the Ligurians then controlled the western extremity of the world known to the Greeks. This fragment has been considered valid by H. A. de Jubainville, C. Jullian or more recently by G. Barruol, G. Colonna or F. M. Gambari. However, today it is often considered inauthentic, due to the discovery of a 3rd century AD Egyptian papyrus. C. that cites the Libyans instead of the Ligurians. It is conjectured that the papyrus may contain a transcription error.

Rufus Festo Avieno, in his Latin translation of an ancient travel tale, probably Massaliote [citation needed], dated to the end of the century VI a. C., indicates that the ancient Ligurians would have spread to the North Sea, before being pushed back (or assimilated) by the Celts[citation needed] to the Alps. Avieno also places Agde on the border between the territory of the Ligurians and that of the Iberians.[citation required]

According to the fragments cited by Stephen of Byzantium of Hecataeus of Miletus in his Europa it presented at the end of the century VI a. C. to Marseille as a Ligistic population and to the Elysians as a Ligurian tribe.[citation required]

The Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax, written between the end of the VI century a. C. and IV, gives the following indications:

III. Ligures and iberos. After the Iberians, the ligurines and the Iberians are inhabited until the Rhone. Navigation from Ampurias to the Rhone was two days and one night.

IV. Ligures. Beyond the Rhone following the ligurines to Antion. In this region is the Roman city of Massalia with its port.

The Pseudo Scymnus, based on sources from the IV century a. C., describes Liguria as a coastal region between Emporion and the settlement area of the Tyrrhenians. He also claims that the Celts were the greatest people in the West. [citation required]

Aristotle (IV century BC), located in his Meteorological the underground course of the Rhône near Bellegarde-sur-Valserine, in Liguria[ citation required]. According to Herodotus, the Ligurians controlled the western Mediterranean.

They were located by the Latin authors in the Italian region of Liguria in northwestern Italy and the Maritime Alps (also in the Italian geographical area) which corresponds to ancient Liguria between the Var and Magra rivers. They claim that they would have even occupied a much larger territory: in Italy (Piedmont, Tuscany, Umbria and Lazio), to the west in Languedoc[citation needed], including in the Iberian Peninsula).

The Roman Republic came into hostile contact with the Ligurians after the First Punic War and since its implantation in Northern Italy. The Roman historian Florus thus describes the people the Romans were fighting during the Ligurian War (239-173 BC):

The ligurines, lying at the bottom of the Alps, between the Var and Magra rivers, and hidden in the middle of the bushes, were more difficult to find than to overcome. With the security that provided them with their retreats from the battlefield and for their promptness to flee, this infatigable and agile race was given more to banditry than to war.; finally, Quinto Fulvio Flaco surrounded his dens with vast fires; Lucio BebioDivite made them descend to the plain, and Postumio totally disarmed them so that he only left them with iron tools to cultivate the land.Lucio Anneo Floro, Compendium of Roman History ii.3 Book II in (French)

Tito Livio refers that around the year 189 B.C. C., the Ligurians inflicted a military setback on the Roman legion of Lucio Bebio who surrendered in Hispania.

Sallust and Plutarch relate that during the Jugurtha War (112-105 BC) and the Cimbrian War (104-101 BC) the Ligurians served as auxiliary troops in the Roman army. In the course of this last conflict they played an important role in the battle of Aquae Sextae.

In the year 49 a. C. the Ligures, through the Lex Roscia, and like all the other peoples of the Northern Italy, they obtained full Roman citizenship; while, in the year 42 a. C, by the will of Julius Caesar, the land of the Ligurians, together with the other territories of northern Italy, was definitively and legally annexed to the territory of Roman Italy.

Army

Diodorus Siculus describes the Ligurians as very fearsome enemies: despite not being particularly physically impressive, their strength and tenacity make them the most dangerous warriors. As proof of this, Ligurian warriors were highly regarded as mercenaries and many Mediterranean powers, such as Carthage and Syracuse, went to Liguria to raise armies for their expeditions (for example, Hannibal's elite troops consisted of a contingent of Ligurians)..

Tactics, unit types and equipment

The weapons varied according to which class the owner belonged to, in general most of the warriors belonged to the light infantry, poorly armed. The main weapon was the spear, with spikes that could exceed a cubit (approximately 45 cm), followed by the sword, gallery (sometimes cheap because it is made of soft metals)[citation needed], warriors were very rarely equipped with bows and arrows.

The protection was entrusted to a wooden shield, always of Celtic typology (but unlike of the latter without a metallic element) and a simple helmet, of the Montefortino type.[citation required]

The horned helmets, recovered in the area of the Apuan tribe, were used only for ceremonial purposes: the warrior wore it to underline his virility and military skills. The use of the armor was not known: that of the seated warrior from the site of Roquepertuse looks, from wear, like leather armor, despite the fact that the statue is attributable to the V d. C. And the armor was perhaps used only in this period. It is even possible that the richest warriors possessed armor of organic material like the Gauls[citation needed] or linothorax like the Greeks.

The infantry was good at ranged combat as a peltast, but could fight hand to hand when necessary.

Cavalry

Strabo and Diodorus Siculus say they fought almost on foot due to the nature of their territory, but cavalry was not entirely unknown, Strabo says that the Salyes, a tribe he located north of Massalia, have a substantial cavalry force, but these were one of several Celto-Ligurian tribes, and the cavalry probably reflects the Celtic element [citation required]

Mercenaries

The Ligurians seem to have always been ready to commit mercenary troops to the service of others. Auxiliaries are mentioned in the army of the Carthaginian general Hamilcar I in 480 BC. Greek leaders in Sicily continued to recruit Ligurian mercenary forces from the same quarter as late as the time of Agathokles.

The mercenary trade was a particular form of income: as Greek and Roman sources attest, since very ancient times the Ligurians had served as mercenaries in the armies of the western Mediterranean. Enlistment took place by contingents (evidently not for individual soldiers) when it was essential to have well-functioning units. Centuries of combat experience in the wars with the Phoenicians, Etruscans, Phocaeans, Romans, and much later with the Germanics (Cimbri and Teutons) provided the Ligurians with sufficient fighting skills to fend off Roman legions for nearly two centuries and sell their fighting skills..

Hacking

In ancient times, an activity parallel to navigation was piracy, and the Ligurians were no exception. If they deemed it appropriate, they would attack and pillage ships that sailed along the coast. The thing is not surprising: even in ancient times the fastest way to get goods is to steal them. After all, the continuous incursions of the Ligurian tribes into the territories of neighboring peoples are well documented and constitute an important voice in their economy. The Ingauni, a tribe of sailors located around Albingaunum (today Albenga) were famous for engaging in trade and piracy: hostile to Rome, they were subdued by the consul Lucio Emilio Paulo Macedónico in the year 181 BC. c.

In the Roman army

After the Roman conquest, in 171-168 some of them fought with the Romans against the Macedonians, around the time of Gaius Mario, with which their presence became more common in the Roman army.

According to Plutarch, the battle of Pydna, the decisive confrontation of the third Macedonian war, began in the afternoon, thanks to a trick devised by the Roman consul L. Emillius Paullus. In order to make the enemies move into battle first, push before a horse without reins the Romans rushed against them, and the pursuit of the horse began the attack. According to another theory, instead, the Thracians in the service of the Macedonians attacked some Roman scouts who had come too close to the enemy lines, and the response from there was the immediate charge of 700 Ligurian auxiliaries.

Before Pydna the Romans used their Ligurian auxiliaries with the velites to chase down the peltasts.

Sallust and Plutarch say that during the Ligurian War of Jugurtha from 112 to 105, and during the Cimbrian War from 104 to 101, Ligurians served as auxiliary troops in the Roman army. In the course of the latter conflict they played a role important role in the battle of Aquae Sextae.

Language

No text is available in the Ligurian language. He is known by some proper names (ethnonyms, place names, anthroponyms) and some terms cited in ancient sources. Herodotus points out that the word sigynna would mean "merchant" According to Pliny the Elder, the Ligurians called the river Po Bodincus, meaning "bottomless", and rye it was called asia in the language of the Taurini.

Ligurian has phonetic similarities to both Italic and Celtic languages, but its vocabulary is close to Celtic[citation needed]. The Ligurian ethnonyms do not, however, have an Indo-European etymology. For this reason some authors such as the historian and Celtologist Henri d'Arbois de Jubainville consider it an Indo-European language. Some authors (Benvenuto Terracini, Paul Kretschmer, Hans Krahe), to explain the presence of non-Indo-European ethnonyms, have conjectured that an Indo-European people would have imposed their dominance on the pre-Indo-European populations. As for Bernard Sergent, he considers Ligurian to be a Celtic language.

The Ligurian influence is attributed to the place names -ascu, -oscu, -uscu, -incu or -elu. Among the types -ascu, -oscu or -uscu we can cite Manosque, Tarascon, Venasque, Artignosc, Branoux, Flayosc, Gréasque, Vilhosc, Chambost, Albiosc, Névache, Grillasca, Palasca i>, Popolasca, Salasca, Asco in France and Benasque, Velasco or Huesca in Spain. Arlanc, Nonenque and the old name of Gap (Vappincum) are of the type -incu. The type -elu is represented by Cemenelum (present-day Cimiez).

The study of toponymy has revealed the presence of Ligurian elements not only in the south of the Alps and in the northwest of the Apennines, but also in Italy: in Piedmont, Tuscany, Umbria, Lazio, as well as in the Languedoc[citation required ] and in some parts of the Iberian Peninsula. It is also the case in eastern Sicily, in the country of the Elymus, in the valley of the Rhône[citation needed] and in Corsica (Grillasca, Palasca, Popolasca, Salasca, Asco).

Archaeology

In 1927, Joseph Déchelette found that the Ligurian burial mounds in the Rhône Valley are identical to those erected by the Celts.

In 1955, Jean Jannoray published an analysis of the excavations at the archaeological site of Ensérune, in which he underlined the continuity of settlement of the archaeological sites of Mediterranean Gaul and stressed the impotence of archaeologists to identify the properly Ligurian contributions between the archaeological vestiges.

At the end of the 20th century, archeology revealed the progressive Iberianization of Roussillon and Languedoc between the 7th and 5th centuries B.C. C., subsequent to the development of commercial exchanges with the Phoenician world.

Interpretations

The indications provided by ancient authors regarding the extension that the Ligurians reached in some regions of France (Languedoc), Italy (Tuscany, Umbria, Lazio) and Spain, seem confirmed by the study of the onomastics of these regions. Even the name days of Sicily, the Rhône Valley, Corsica and a part of Sardinia suggest a Ligurian presence.

However, Roger Dion has put forward the hypothesis in 1959, that the Greek authors called Ligurians the set of less civilized tribes of the western Mediterranean and that the term would not designate a specific people in the ancient writings.

Traditionally they have been considered as an indigenous people of southern Gaul, with which successively the Iberians and the Celts mixed. This position was defended above all by Roget de Belloguet and Camille Jullian. Camille Jullian supported the thesis of a considerable Ligurian expansion (Italy, Spain, Gaul, British Isles) and, like Henri Hubert, that of an Iberian invasion from the west of the Ligurian territory. There are, however, other hypotheses: in 1866, that of Amédée Thierry that the Ligurians arrived from Spain in the 17th or 16th century BC when they were expelled by Gallic peoples. In 1940, the hypothesis of Albert Grenier pointed to consider them as a population very close to the Celts.

Until the second half of the XX century they were presented as primitive tribes, colonized by the Greeks from the VII a. C., by the Celts from the century IV a. C., although the Celtic colonization is not attested neither by ancient sources, nor by archaeology. In the 1970s, the reality of these Celtic invasions was questioned, especially by Michel Py; later in the 1980s and 1990s, the notion of acculturation by the Greeks was discussed. In 1999, Danièle and Yves Roman defended the principle of Celtic incursions into southern Gaul, at least from the VI century BCE. C., and considered the Ligurians as an autochthonous people in their work Histoire de la Gaule .

Their expansion took place before that of the Celtic and Italic peoples. They were overwhelmed in the VII century, from the west of their territory by the Iberians, who repulsed them to the east of the Hérault river, and later to the Rhône, but at present this expansion is seen more as the consequence of a commercial development than of a warlike invasion. The strength of the Massalia colony made the Ligurian culture retreat. Later, they also had to retreat before the Celtic advance. In Italy, they were rejected by both the Celts and the Etruscans. Finally, they were definitively integrated into Roman Italy by the will of Julius Caesar and their territory framed as Regio IX Liguria, among the eleven regions within the Italy of Augustus.

Contenido relacionado

Tanned

Eisenach

History of iraq