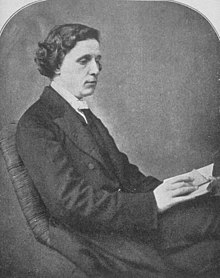

Lewis carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Daresbury, Cheshire, United Kingdom, January 27, 1832-Guildford, Surrey, United Kingdom, January 14, 1899), better known by his pseudonym Lewis Carroll, was a British Anglican deacon, logician, mathematician, photographer and writer. His best-known works are Alice in Wonderland and its continuation, Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There .

Biography

Family, childhood and studies

Dodgson's ancestors came mainly from the north of England, with some Irish connections. Conservatives and members of the Anglican High Church, most of them dedicated themselves to the two characteristic professions of the English upper-middle class: the army and the Church. His great-grandfather, also called Charles Dodgson, his grandfather, another Charles

The eldest of them—also named Charles—chose an ecclesiastical career. He studied at Westminster School and later at Christ Church, Oxford. Mathematically gifted, he earned a double degree that promised to be the beginning of a brilliant academic career. However, the future father of Lewis Carroll preferred, after marrying his cousin in 1827, to become a rural parish priest.

Their son Charles was born in the small parish of Dareso, in Cheshire. He was the third of the Dodgsons' children, and the first boy. Eight more children would follow and, most unusual for the time, all of them—seven girls and four boys—would survive to adulthood. When Charles was eleven years old, his father was appointed parsonage of the North Yorkshire town of Croft-on-Tees, and the whole family moved into the spacious rectory that would be the family home for the next 25 years.

Dodgson Sr. rose through the ecclesiastical ranks: he published several sermons, translated Tertullian, became Archdeacon of Ripon Cathedral, and took an active part in the passionate discussions that then divided the Church of England. He was a supporter of the High Church and favorable to Anglo-Catholicism; he admired John Henry Newman and the Tractarian movement, and did what he could to pass his views on to his children.

Young Charles began his education in his own home. The reading lists of his kept by the family attest to his intellectual precocity: at the age of seven he read The Pilgrim ’s Progress by John Bunyan. It has been said that he suffered a childhood trauma when forced to counteract his natural tendency to be left-handed; there is, however, no evidence that he was so. Yes, he suffered from a stutter that would have detrimental effects on his social relationships throughout his life. He also suffered from deafness in his right ear as a result of an illness. At twelve he was sent to a private school outside Richmond, where he seems to have fitted in well, and in 1845 was transferred to Rugby School, where he was evidently somewhat unhappy, he wrote some years after leaving the place:

I think... for nothing in this world would come back to live the three years I spent there... I can honestly say that if I had been... safe from the nightly trouble, the hardness of day life would have been made, in comparison, much more bearable.

The nature of this "night trouble" will perhaps never be correctly interpreted. It can be a delicate way of referring to some kind of sexual abuse. Academically, however, Charles managed quite well. His mathematics teacher, R.B. Mayor, said of him: "I haven't met a more promising boy since I've been at Rugby."

He left Rugby in the late 1850s and in January 1851 transferred to Oxford University, where he entered his father's old college, Christ Church. He had only been in Oxford for two days when he had to return to his house because his mother had died of "inflammation of the brain" (possibly meningitis) at the age of forty-seven.

Whatever feelings his mother's death produced in Dodgson, he did not allow them to deter him from the goal that had brought him to Oxford. Perhaps he didn't always work hard, but he was exceptionally gifted and easily achieved excellent results. His early academic career oscillated between his successes, which promised an explosive career, and his irresistible tendency to be distracted. Because of his laziness, he lost an important scholarship, but even so his brilliance as a mathematician won him, in 1857, a professorship of mathematics at Christ Church which he would hold for the next 26 years (although he does not seem to have particularly enjoyed it). of your activity[citation required]). Four years later he was ordained a deacon.

At Oxford, he was diagnosed with epilepsy, which at the time constituted a considerable social stigma. However, recently John R. Hughes, director of the University of Illinois (Chicago), has suggested that there may have been a diagnostic error[citation needed] .

Carroll and photography

Dodgson soon achieved excellence in this art, which he converted into an expression of his personal inner philosophy: the belief in the divinity of what he called beauty, which for him meant a state of moral, aesthetic or physical perfection. Through photography, Carroll sought to combine the ideals of freedom and beauty with Edenic innocence, where the human body and human contact could be enjoyed without guilt. In his middle age, this vision became the pursuit of beauty as a state of grace, a means to recover lost innocence. This, together with his passion for the theater, which accompanied him throughout his life, would bring him problems with Victorian morality, and even with the Anglican principles of his own family. As his chief biographer, Morton Cohen, notes: "He flatly rejected the Calvinist principle of original sin and substituted for it the notion of innate divinity."

The definitive work on his activity as a photographer (Lewis Carroll, Photographer, by Roger Taylor [2002]), exhaustively documents each of Lewis Carroll's surviving photographs. Taylor estimates that just over half of his surviving work is dedicated to portraying girls. However, it must be taken into account that less than a third of all of his work has been preserved. The girl who most often served as his model was Alexandra Kitchin ("Xie"), daughter of the dean of Winchester Cathedral, whom he photographed about fifty times from the age of 4 to the age of 16. In 1880 he attempted to photograph her in a dress bathroom, but he was not allowed. Dodgson is alleged to have destroyed or returned the nude photographs to the families of the girls he photographed. It was believed that they had been lost, but six nudes have been found, of which four have been published and two are barely known. Dodgson's nude photographs and sketches encouraged the assumption that he had pedophilic tendencies, although such speculation has been challenged by several academics who argue that Carroll must be understood in context and, among other things, that in the space and time of In Victorian culture, the appearance of naked girls was seen as completely normal because it was equivalent to a symbol of innocence, (similar scenes appearing even on Christmas cards). It has also been argued that there have been inconsistencies and later manipulations in biographies, which contributed to speculation of what has been dubbed "the Carroll myth".

Photography was also useful for him as an entry into high social circles. When she managed to have her own studio, she made notable portraits of important people, such as John Everett Millais, Ellen Terry, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Julia Margaret Cameron and Alfred Tennyson. She also cultivated the landscape and the anatomical study.

Dodgson gave up photography suddenly in 1880. After 24 years, he was in complete command of the medium, running his own studio in the Tom Quad neighborhood, and had created some 3,000 images. Fewer than 1,000 have survived time and deliberate destruction. Dodgson carefully recorded the circumstances surrounding the creation of each of his photographs, but the record of him was destroyed.

Her work was recognized posthumously, along with that of Julia Margaret Cameron, thanks to her vindication by photographers of pictorialism, as well as the support of the Bloomsbury Circle, which included Virginia Woolf. Today, he is considered one of the most important Victorian photographers, and certainly the most influential in contemporary fine art photography.

Literary career

Dodgson wrote poetry and short stories, which he submitted to various magazines and met with modest success. Between 1854 and 1856 his work appeared in the national publications The Comic Times and The Train, as well as in smaller magazines such as the Whitby Gazette and the Oxford Critic.

Most of Dodgson's writing is humorous, and occasionally satirical. But he had a high level of self-demand. In July 1855 he wrote: "I do not think I have yet written anything worthy of real publication (which did not include the Whitby Gazette or the Oxonian Advertiser ), but I don't despair of doing it one day." Years before Alice in Wonderland, he was looking for ideas for children's stories that could bring him money: "A Christmas book [that could] sell well... Practical instructions for building puppets and a theater".

In 1856 he published his first work under the pseudonym that would make him famous: a predictable little romantic poem, "Solitude", which appeared in The Train signed by Lewis Carroll. His nickname was created from the Latinization of his name and his mother's surname, Charles Lutwidge. Lutwidge was Latinized as Ludovicus, and Charles as Carolus. The resultant, Ludovicus Carolus, returned again to the English language as Lewis Carroll.

Also in 1856, a new dean, Henry Liddell, arrived at Christ Church, bringing with him his young wife and daughters, who were to play an important role in Dodgson's life. He developed a great friendship with his mother and with the children, especially with the three daughters, Lorina, Alice and Edith. It seems that it became something of a tradition for Dodgson to take the girls on picnics to the river, at Godstow or Nuneham.

It was on one of these excursions, specifically, according to his journals, on July 4, 1862, that Dodgson invented the plot of the story that would later become his first and greatest commercial success. He and his friend, the Reverend Robinson Duckworth, took the three Liddell sisters (Lorina, thirteen, Alice, ten, and Edith, eight) for a boat ride on the Thames. According to Dodgson's own, Alice Liddell's, and Duckworth's accounts, the author improvised the narrative, which the girls, especially Alice, were enthusiastic about. After the excursion, Alice asked him to write the story. Dodgson spent a night composing the manuscript, presenting it to Alice Liddell the following Christmas. The manuscript was entitled Alice's Adventures Underground (Alice's Adventures Under Ground), and was illustrated with drawings by the author himself. The play's heroine is speculated to be based on Alice Liddell, but Dodgson denied that the character was based on any real person.

Three years later, Dodgson, moved by the great interest that the manuscript had aroused among all his readers, took the book, suitably revised, to the publisher Macmillan, who liked it immediately. After shuffling the titles of Alice Among the Fairies and Alice's Golden Hour, the work was finally published in 1865 as Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. wonders (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland), and signed by Lewis Carroll. The illustrations in this first edition were the work of sir John Tenniel.

The success of the book led its author to write and publish a second part, Alice Through the Looking-Glass (Through the Looking-Glass and what Alice Found There).

Later, Carroll published his great parody poem The Hunting of the Snark, in 1876; and the two volumes of his last work, Silvia and Bruno, in 1889 and 1893, respectively.

He also published many articles and books on mathematics under his real name. Worthy of note is The Game of Logic and Euclid and His Modern Rivals, as well as An Elementary Theory of Determinants written in 1867. In the latter, he gives the conditions by which a system of equations has non-trivial solutions.

Carroll and mathematics

Although Carroll devoted most of his attention to geometry, he also wrote on numerous other mathematical subjects: squaring the circle, message encryption (even inventing some methods), algebra, electoral arithmetic, and voting, as well as logic.

In the last years of his life he paid attention not only to recreational mathematics (with calculation games like the ten knots in his book A Tangled Tale) or to study of paradoxes (he analyzed the paradox of Achilles and the tortoise and developed his own, that of the barbershop), but also devoted himself to the search for ways of systematic exposure of, for example, the theory of syllogism. Otherwise, he produced Venn-type charts, cards, and diagrams and introduced logic trees.

Speculations and unknowns

Drug use

There has been a lot of speculation that Dodgson was using psychoactive drugs, although there is no evidence to support this theory. However, most historians consider it likely that the author used laudanum from time to time, a fairly common pain reliever at the time that would help him with the pain of his arthritis. It should be noted that this substance comes from opium, and can produce psychotropic effects if used in large enough doses. Despite this, there is no evidence to suggest that Dodgson abused narcotics, or that they had any influence on his work. On the other hand, some [who? ] have believed they saw in the hallucinations suffered by his character, Alicia, a reference to psychedelic substances. For example, in the case of the Amanita muscaria, which produces macropsia and micropsia.

Pastor Ministry

Dodgson was destined to end up as a pastor, given his resident status at Christ Church. However, he would begin to reject this idea, delaying the time to become a deacon until December 1861. When a year later, it was his turn to take the next step to become a pastor, he appealed to Liddell not to continue. This attitude was not compatible with the norms, and Liddell himself told him that he would probably have to leave his job if he resigned from the ministry, although he would consult with the governing body of the institution, something that undoubtedly would have led to an expulsion. For unknown reasons, Lidell changed his mind and allowed Dodgson to stay and never reach the ministry of pastor.

There is no conclusive clue as to why Dodgson avoided becoming a pastor. Some have pointed out that his stuttering may have influenced the decision, so that he would have been afraid to give sermons. However, Dodgson did not shy away from public speaking, nor did he have any problem with performances such as storytelling, or putting on magic shows. In addition, in his last stage, he would come to preach, despite not holding the status of pastor.

Lewis Carroll suspected of being Jack the Ripper

Although he was always considered a harmless dreamer, in 1996 author Richard Wallace did not hesitate to accuse him of having been the man who was hiding under the alias of Jack the Ripper. The alleged evidence that allegedly accused him were cryptic phrases contained in his books nineteen years before the massacre in the autumn of 1888. According to this interpretation, the already unbalanced writer left clues there anticipating the crimes he planned to commit.

Works

Some works by Lewis Carroll

- Alice in Wonderland (Alice's Adventures in Wonderland(1865), published in Spanish by Ed. Siruela, ISBN 84-7844-760-1.

- Alicia through the mirror (Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There(1872), published in Spanish by Ed. Gaviota, ISBN 84-392-1611-4.

- The Snark Hunt (The Hunting of the Snark(1875), published in Spanish by Editorial Mascaró, Barcelona, 1981, ISBN 84-264-2837-1.

- The game of logic (The Game of Logic(1876), published in Spanish by Editorial Alliance, ISBN 84-206-7757-4.

- A tale swept up (A Tangled Tale(1885), published in Spanish by Nivola books and editions, ISBN 84-95599-33-3.

- Silvia and Bruno (Sylvie and Bruno(1889), published in Spanish by Edhasa, ISBN 978-84-350-4010-5.

- Alicia for the little ones (The Nursery Alice.(1890)

- Journal of a trip to Russia (The Russian Journal), published in Spanish by Nocturna Ediciones, ISBN 978-84-937396-0-7.

- Mathematically, selection by Leopoldo María Panero of stories written by Carroll related to mathematical problems. Published by Ediciones Tusquet, ISBN 978-84-8310-641-9.

Correspondence

- Girls. Lumen, 1998, ISBN 978-84-264-2314-6.

- Unpublished letters to Mabel Amy Burton, Night Editions, 2010, ISBN 978-84-937396-4-5.

- The man who loved the girls. Correspondence and portraitsLa Felguera, 2013, ISBN: 978–84–937467–8–0

Contenido relacionado

Eritrean flag

Kenyan flag

Navarre (disambiguation)