Lepidoptera

The lepidoptera (Lepidoptera, from the Greek λεπίς, lepís: 'scale', and πτερόν, pteron: 'ala') are an order of holometabolous insects, almost always flying, commonly known as butterflies; the best known are the diurnal butterflies, but most of the species are nocturnal (moths, sphinxes, peacocks, etc.) and go largely unnoticed. Its larvae are known as caterpillars and typically feed on plant matter, so some species can be very damaging pests for agriculture. Many species fulfill the role of pollinators of plants and crops.

This taxon represents the second order with the most species among insects (being surpassed only by the order Coleoptera); in fact, it has more than 165,000 species classified into 127 families and 46 superfamilies. The largest day butterfly that exists is the female Ornithoptera alexandrae, which can reach a wingspan of 31 cm (the male is slightly smaller), lives in southeastern New Guinea. The largest lepidopteran that science has discovered is the well-known Atlas butterfly or Atlas moth (Attacus atlas), native to the tropics of Southeast Asia and is a heterocera (moths or moths) although it is of daytime habits.

Systematics

Taxonomy

There are about 127 families within the order Lepidoptera, but opinions of which these are often change among scientists. The treatment given here is that adopted by the London Natural History Museum database.

For many years, the order Lepidoptera was subdivided into two suborders, the Ropaloceras, or moths, and the Heterocera, moths, or moths. Modern cladistics has shown that this ancient classification is artificial, and the suborders Aglossata, Heterobathmiina, Zeugloptera, and Glossata are now admitted. The first three contain a few species, while Glossata includes 99% of extant Lepidoptera.

- Suborden Zeugloptera

- Suborden Aglossata

- Suborden Heterobathmiina

- Suborden Glossata

- Infraorden Heteroneura

- Ditrysia Division

- Cossina Section

- Tineina Section

- Monotrysia Division

- Ditrysia Division

- Infraorden Dacnonypha

- Infraorden Lophocoronina

- Infraorden Exoporia

- Infraorden Neopseustina

- Infraorden Heteroneura

Phylogeny

The phylogenetic relationships of the four suborders are as follows:

| Lepidoptera |

| ||||||||||||||||||

Fossil Lepidoptera

There are very few butterfly fossils when compared to other groups of insects. The distribution and abundance of the most common fossils indicate that there must have been large migrations of butterflies during the Paleogene in the North Sea, which is where many fossils of this group are found.

Some fossils are also found in amber and some fine sediments. Remains left by leafminer larvae May be valuable, but interpretation is not easy.

Features

Butterflies have two pairs of membranous wings covered in colored scales, which they use for thermoregulation, courtship, and signaling. Their mouthparts are of the proboscis type, equipped with a long proboscis that is coiled in a spiral (spiritrompa) that remains coiled in a state of rest and which serves to drink the nectar of the flowers that they pollinate.

Male courtship is highly variable in the different families of the order, but basically consists of displays and the production of sexual pheromones. With the flight maneuvers the males cover the females with the scent of these pheromones. After mating, the males can prevent the female from copulating again by plugging her genitalia with a sticky secretion.

Its development is holometabolous: a larva or caterpillar emerges from the egg that will transform into a pupa and this will give rise to the adult. The larva, unlike the adult, has a chewing mouthpiece; most of the larvae are phytophagous. In less than 1% the larvae are carnivorous or even cannibalistic. We can distinguish the larvae of Lepidoptera from those of other insects because they have a series of five false legs —those of the Symphyte Hymenoptera have seven or more— at the end of the abdomen, which in some cases means that their way of walking is like the of an accordion opening and closing alternately. Lepidoptera are terrestrial insects and only occasionally some larvae are aquatic.

Coloring

In the order Lepidoptera the coloration, especially that of the wings, reaches the maximum specialization. Morphologically, the wing surface is covered with scales whose surface has a multitude of longitudinal edges (separated sometimes less than 1 μm, that is, one thousandth of a millimeter) that alter the reflection of light, producing very striking and often iridescent colors. and iridescent.

Wing Venation

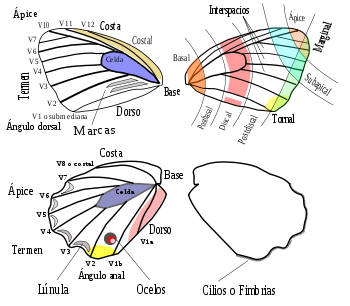

The veins of the wings of butterflies form a characteristic and unique design depending on the species or families in question. Knowing this pattern is, in some cases, essential for the correct determination of a specific species of butterfly. In order to describe this design clearly and precisely, the following entomological terminology is used:

- Both the previous wings and the subsequent ones are the following areas or areas: basal, is the closest to the body, sometimes subdivided into basal and postbasal; submarginal, premarginal or, simply, marginal, is the most remote. Between both is the discal zone which, in turn, is divided into discal and postdiscal or postmedial. Finally, the apical area is located on the distal and upper part of both wings.

- In the perimeter of the previous wing is the border of attack that is called coastline or coastline. Then the apex followed by the external margin or end. Immediately afterwards, in the previous wings appears the dorsal angle and, in the later, the anal angle. The periphery of the wing is completed with the internal margin or back.

- Between the basal and discal zones of both wings, near the coast, there is an elongated area, framed by veins and almost always closed, called cell or cell discal, discoidal, discocelular, or, simply, cell. At the top it is defined by the subcostal vein, at the bottom by the medium vein, and by the post-discal by the three discidal veins. When one of these veins is missing, it is called an open cell.

- The veins are not always easy to observe, sometimes it is better to observe them from the back or use alcohol humidification techniques to make them visible between the scales and androconial hairs. Those of the previous wing are numbered from 1 to 12 (V1, V2,..., V12), from below. The V1 or submedian vein, of the most difficult to appreciate, is born at the base and runs parallel to the back. The V2 or median starts at the middle of the lower edge of the cell. The V12 or coastal vein is born at the base of the wing and runs parallel to the coast. The ones in the rear wing are 8, although there are often two V1, V1a and V1b annal veins. They are also numbered from the bottom up, being the V8 the rib vein. Some butterflies may lack veins, both from one wing and the other, usually between the V6 and the V9. In these cases they are numbered successively, so there may be butterflies in which the last vein is the V9.

- Among the veins are the spaces called cells that are also numbered. Thus, between the back and V1 is the E1a cell; between V1 and V2 appears E1b; between V2 and V3 E2; and so on until reaching E12 in the previous wing, and E8 in the later, between the last vein and the coast. As in the case of veins, the numbering is always correlative, being able to end in E9.

Pattern formation in color

The butterfly wing develops in the larva as an epidermal sac (imaginal disc) which invaginates in metamorphosis to form an immobile wing during the pupal stage. Pigmented scales are secreted in the late pupal stage, but epidermal cell interaction is determined in earlier stages and determines the scale color defining pattern in the adult. For its part, the eye spot is specified from a signaling in the central region (French, 1997). On the other hand, it is believed that the color pattern is organized around a hypothetical focus and that this serves as a source of information for the position and synthesis of the appropriate pigment. The specific pattern appears from the variations in the number of foci on the wing and the variation in which position information is interpreted.

Another study showed the existence of a focus that determines the length of the eyespot on the hindwing of Precis coenia. By cauterizing three hundred cells in the center of the putative eyespot in early wing development, wing development can be completely inhibited. These same cells can be transplanted to another region of the wing and induce a ring-shaped pigment in the tissue around the graft. This study demonstrated that the focus is a physiological entity.

Histological studies on the wing epithelium revealed that scale formation always occurs in parallel rows, close to the wing axis. This cell formation of the wings appears to be formed by differentiation in situ and not by migration. The pigments that generate the color pattern in the wings are synthesized exclusively in the scales. This pattern is formed by four different melanin colors; the specific enzymes for its synthesis are incorporated in insoluble forms in the cuticle of the scales. The synthesis of these pigments begins when the melanization substrate begins to be supplied by the circulatory system.

Finally, it has been found that the expression of homologous genes in the pattern of Drosophila appendages are also involved in the color pattern. The angrailed gene is expressed on the posterior and apterous on the dorsal surface of the wing disc. For its wingless part it is expressed around the dorso-ventral margin on the wing disc. The Wg protein together with the Decapentaplegic gene have been shown to have a function as a morphogen gradient in Drosophila controlling gene expression and consequently the morphological pattern in the dorso-vetral and antero axes. -back.

Food

Caterpillars feed on the plant matter that surrounds them: leaves, flowers, fruits, stems, roots, which gives them great agricultural importance as they constitute important crop pests. Some species are specialized in one or a few related species, others are polyphagous, able to feed on a wide variety of plants from different families. Some species are capable of mining (tunneling) into the surfaces they feed on. Others, on the other hand, take advantage of human manufactures, or stored products (flour, grains,...).

A small number of species are carnivorous. The families Epipyropidae and Lycaenidae are noteworthy.

Adults, with the exception of the representatives of the Micropterigidae family (whose diet, derived from their chewing capacity, includes pollen, fungal spores, etc.), feed by sucking, that is, absorbing nectar or other liquid substances through its licking-sucking mouthparts (spiritrompa). However, there are species whose life cycle requires a short imago phase: in these cases, the adult does not even eat, but instead devotes all its energy to reproduction.

Life Cycle

Reproduction and development

Lepidoptera are holometabolous insects, that is, they undergo complete metamorphosis and go through the stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult or imago. The vast majority of butterflies are herbivorous, meaning they feed on plants. Only a few species are carnivorous or eat wool or other materials.

Egg

Most Lepidoptera are oviparous, although a few are ovoviviparous. The female can lay the egg on a variety of substrates. Some species lay eggs on the fly. In this case, they are species that can feed on a wide variety of plants (polyphagous). The more specialized species deposit their eggs on or near the host plant. Some species lay single eggs, others do so in masses. Females select host plants instinctively, using mainly chemical or odor signals.

The egg stage can last a few weeks or less; in other cases, the egg goes into diapause during the winter and the larva emerges only the following spring.

Larva or caterpillar

They hatch as worm-like larvae called caterpillars. The body consists of thirteen segments, three thoracic and ten abdominal.

Most species feed on leaves, stems, or other parts of plants while growing rapidly. Many species require one or a few species of plants for food, and the extinction of one plant can bring about the extinction of a species of butterfly. Other species feed on a wide variety of plants from different families, they are polyphagous. Still others (very few) are carnivorous or detrimental.

Pupae

When development is complete, the caterpillar takes shelter in a sheltered place and there it transforms into a pupa. The pupa may be wrapped in a silk cocoon, as in most moths, or it may lack a silk cocoon, as in chrysalis butterflies. At this stage it does not feed, and undergoes great metabolic and morphological changes, the whole of which is called metamorphosis. The adult butterfly emerges by breaking the external skeleton of the chrysalis.

Adult or imago

Most adult butterflies feed by sipping nectar from flowers with their spirituscus, an extendable mouth structure evolved from some of the typical jointed mouthparts of insects. Adults of a few species are very short-lived, lack mouthparts, and do not feed.

This "rolled tongue" It is flexible and very sensitive. It can be inserted inside a flower, but it can also be tilted steeply, so that the butterfly can feed from different angles without even having to move its skeleton. Once the butterfly has finished feeding, the tongue curls back and fits exactly under the insect's head. Males and females actively search for each other, using their characteristic wingbeats as a visual guide, and employing the sense of smell. After fertilization, the female lays several hundred or thousands of eggs. In some cases, adult life is brief, lasting no more than the time necessary (sometimes a single day) to ensure reproduction.

Migration

Some species are migratory. Among them, some are among the insects that cover the greatest distances in their travels.

Among the best-known migratory species are the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus plexippus), the sphinx hummingbird (Macroglossum stellatarum), the common thistle (Vanessa cardui), the red admiral (Vanessa atalanta) and Colias croceus. Another example is Urania fulgens which can have explosive migrations in certain years in the Neotropics.

Contenido relacionado

Dichanthelium

Human embryology

Goniothalamus