Lenin

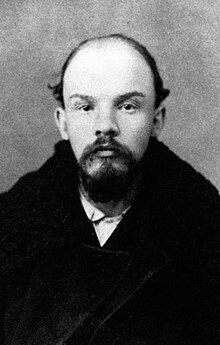

Vladimir Ilich Uliánov(in Russian, Вльянов, romanization Vladimir Il'ič Ul'janov,pronunciation ![]() [vl]ðdjimj α εхljit] ・ljanambif] (?·i)), aliases Lenin(Lean, [jjjjjjjjjn]; Simbirsk, April 10Jul./ 22 April 1870Greg.-Gorki, January 21, 1924), was a politician, revolutionary, political theorist, philosopher and Russian communist leader. Leader of the Bolshevik sector of the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party (POSDR), became the leading leader of the October Revolution of 1917. In 1917, he was appointed president of the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom), becoming the first and highest leader of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (URSS) in 1922. Politically Marxist, his contributions to Marxist thought are called Leninism, or better known as Marxism-Leninism, a socialist ideology that would expand by most of the "communist bloc" and the "second world" during the Cold War.

[vl]ðdjimj α εхljit] ・ljanambif] (?·i)), aliases Lenin(Lean, [jjjjjjjjjn]; Simbirsk, April 10Jul./ 22 April 1870Greg.-Gorki, January 21, 1924), was a politician, revolutionary, political theorist, philosopher and Russian communist leader. Leader of the Bolshevik sector of the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party (POSDR), became the leading leader of the October Revolution of 1917. In 1917, he was appointed president of the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom), becoming the first and highest leader of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (URSS) in 1922. Politically Marxist, his contributions to Marxist thought are called Leninism, or better known as Marxism-Leninism, a socialist ideology that would expand by most of the "communist bloc" and the "second world" during the Cold War.

He has been a member of the revolutionary political left since his youth. During his university studies he was arrested and exiled for three years in Siberia. He then fled to various Western European countries, and went on to become a leading party theoretician. In 1903, he played a key role in the schism experienced by the POSDR, establishing himself as the leader of the Bolshevik faction, as opposed to the Menshevik faction led by Yuli Martov. He returned to Russia for a short time on the occasion of the 1905 Revolution. In 1914, with the outbreak of World War I, he began campaigning to transform the war in Europe into a revolution of the entire proletariat.

He was the main Bolshevik leader of the October Revolution of 1917. Once in power, Lenin proceeded to apply different reforms that included the transfer to the State or to the Soviet workers of the control of properties and lands in the hands of the aristocracy, the old crown or landowners. Faced with the threat of an invasion by the German Empire, he signed a peace treaty that led to Russia's exit from World War I. In 1921, Lenin's government established the New Economic Policy, which combined socialist and capitalist elements and which began the process of industrialization and recovery of the country after the Russian civil war, a harsh conflict that included the participation of fourteen foreign nations against the new Soviet state.

After his death in 1924, Leninism gave rise to various schools of thought, including Marxism-Leninism and Trotskyism, of Stalin and Trotsky respectively, who both fought for power in the USSR. declaring themselves more faithful followers of Marx and Lenin than the other. Communism became an ideology that had hundreds of millions of followers throughout the world during the 20th century and whose approaches were put into practice by numerous countries, competing for global supremacy with the capitalist system. Lenin continues to be a highly controversial and manipulated figure. He had a very significant influence within the international communist movement and is considered one of the most prominent and influential figures of the XX century.

Biography

Early Years

Born in Simbirsk, a Russian city on the banks of the Volga, in 1870, he was the fourth child of Ilyá Nikolaevich Ulyanov and Maria Alexandrovna Blank. His father, a liberal supporter of Tsar Alexander II's reforms, was a school inspector of the province, a relatively high position in the ranks of the imperial bureaucracy that carried the title of "his excellency", which equated him to the petty nobility. His rise in the state civil service had led him to reach the nobility. hereditary in 1874. Nikolai Ulyanov, Lenin's paternal grandfather, the son of a serf from Astrakhan, was part Kalmyk, an ethnic Mongolian people to whom his wife Anna also belonged. His maternal grandfather Aleksandr Blank (son of Moishe Blank, a merchant from Volhynia and Ana Ostedt, Swedish), was a doctor of Jewish origin converted to Christianity, married to Ana Groschop, from a German Lutheran family. Blank became rich, became a state councilor and in 1847 he retired to his poses ions from Kokushkino, in Kazan, the farm where Lenin spent part of his youth.

His family was a mixture of the ethnicities and religious traditions that then made up the Russian Empire. He was probably of Kalmyk ancestry on his father's side, German, and Swedish on his maternal grandmother, who was also a Lutheran while his maternal grandfather was of Jewish origin. Vladimir himself, known as a child by his diminutive Volodia, was baptized by the rite of the Russian Orthodox Church. Lenin's childhood was conventional, in a happy and cultured family, in a mixture of small landowners on his mother's side and ennobled serfs thanks to his efforts on his father's side. He maintained a close relationship with his family throughout his life. During the usual summer visits to the Kokushkino estate, the children of the family engaged in country activities, including hiking, observing nature, and hunting, which Lenin retained as an adult. The children were good students. and Lenin's older brother, Aleksandr, brilliant in his studies, managed to enter the University of Saint Petersburg, something unusual since Russia barely had about ten thousand university students. Strange at the time, the parents of Lenin educated all his children equally, regardless of their sex.

In his youth, contrary to what some later biographies claim, Lenin showed no interest in politics, he was still religious and his studies focused on the classics and literature. Fyodor Kerensky, the director of the Simbirsk lyceum (and father of Aleksandr Kerensky, later prime minister of the Provisional Government ousted during the Bolshevik revolution) wrote a report on Ulyanov in 1887, his last year at the center, in which he considered him a model student who had never caused problems for the school authorities.

After the death of his father in January 1886 from an unexpected cerebral hemorrhage, Vladimir's brother, Aleksandr Ulyanov, came into contact with a group of students from Saint Petersburg University who followed the revolutionary tradition populist organization of the People's Will (Naródnaya Volia), although they lacked relations with the remnants of this. Almost all of them came from prominent families, among them was, for example, the future Polish leader Józef Piłsudski, they slipped into terrorism and planned an assassination attempt on Tsar Alexander III on March 1, 1887, the sixth anniversary of the assassination of their father, Alexander II. The plot was discovered by the police and its leaders imprisoned in the fortress of Saint Peter and Saint Paul. Aleksandr, who had been in charge of designing and manufacturing the bombs, was finally executed in May in the company of four other leaders. of the conspiracy. He had tried to exonerate the other conspirators, refused repentance, and his mother's attempts to save him from execution proved futile; his death was a hard blow for the family, especially for the young Lenin.Aleksandr's execution coincided with Lenin's final education exams, which did not prevent him from passing with outstanding marks.

Although the death of his brother had an important influence on the development of his ideas, there are no indications that, as has been suggested, his sympathies already turned to Marxist revolutionaries at this time. At first his ideas were strongly influenced by Nikolai Chernyshevsky, who with his novel What to do? (1862) had created the model of the Russian revolutionary hero who lives only for his cause; the novel and the character of the tough revolutionary Rakhmetov served as a model for a whole generation of Russian revolutionaries, such as Sergei Nechayev and the Russian populists of the People's Will. Only slowly, and especially after his arrival in Saint Petersburg in 1893 and his contact with the work of Georgui Plekhanov, he unreservedly adhered to Marxism drawing on its sociological analysis, although characteristically combined with the activism of the People's Will: it was not necessary to wait for the "objective conditions" for revolution to be met, they must also be brought about through political action.

Start of political activity

In the fall of 1887 he entered the Faculty of Law of the University of Kazan thanks to his condition as an excellent student and the great effort of its director Fyodor Kerensky, since the arrest of his brother made admission difficult. Kazan Vladimir, following in his brother's footsteps, came into contact with similar underground circles. He was arrested during the student demonstrations in December of the same year and, probably because of family precedents, expelled from the university with thirty-nine others. classmates. The exact circumstances of the expulsion are unknown, but it is known that the reason for the expulsion was related to the university protests.

The next day, he addressed the following letter to the rector of the University:

Considering that it is not possible to continue my studies at the University in the current conditions of university life, I have the honour to humbly beg His Excellency to grant my exclusion as a student at the Imperial University of Kazan.

He was allowed, however, to continue his studies by correspondence at the university in the capital of the empire. He settled in Kokushkino, near Kazan, under police surveillance. At this time, the young Lenin, intellectually brilliant, he combined his formal education as a law graduate, which ended with excellent grades, with the informal one, in which he became interested in various subjects as a voracious reader. It was in the summer of 1888 in Kokushkino, when he discovered revolutionary literature and He read the novel What to do? by Nikolai Chernyshevski, which influenced him mainly in his visceral rejection of conformism and concessions to the revolutionary ideal.

His requests to readmission to Kazan University, as well as to study abroad or move to Moscow or St. Petersburg, were rejected by the authorities, he eventually obtained permission to return to Kazan in October, where he worked at the study of Karl Marx's Capital, and joined a Marxist circle organized by Nikolai Fedoseev. For several years after his expulsion from the university, Lenin spent much of his time in the countryside, only visiting the city of Kazan. In 1889 his mother inherited an estate in Alakáevka, near Samara, where she tried in vain to get her son to settle. Lenin did not adjust to the life of a small landowner. In May the family moved moved to the farm near Samara, which freed Lenin from being detained during the summer as was the rest of the Marxist circle to which he belonged. During these years, the young Lenin continued his Marxist readings and began to study the reality of empire following these, convention Doing that the incipient capitalism would be the principle that would end the autocracy thanks to the social transformation that was already taking place.

In June 1890, and after several rejected applications, he was authorized to take the external exam in Law subjects at the University of Saint Petersburg and to travel to the capital to take the exams; these were held between September 1890 and the autumn of 1891. During her exams in the spring of 1891, her sister Olga died suddenly of typhus (9 MayJul./ May 21greg.), who also studied in the capital and took care of him; after accompanying his mother at her funeral, they returned to the country estate together for the summer.Lenin's closeness to his family was constant; unable by his exile to be with his mother at her death in July 1916, one of his first actions upon returning to Russia in the spring of 1917 was to visit the grave of Olga and her mother.

In January 1892, he obtained his university diploma with excellent grades despite not having attended any classes, and began practicing as a lawyer's clerk in Samara, where he defended peasants, but in August 1893 he returned to the capital. In July of this year, and after repeated requests to the Samara County Court and the Police Department, he obtained the certification that gave him the right to practice law for the rest of the year, which was renewed the following year. During this time he wrote, for his reading in Marxist circles, some texts against the populists (naródniki ). He practiced intermittently between 1893 and 1894, but by then his interest in revolutionary activity had displaced the legal profession; when in the city Lenin met with revolutionary circles, when he returned to the countryside, he indulged in socialist literature.

At the end of 1893, he moved to Saint Petersburg, stopping along the way in Nizhny Novgorod and Moscow, where he came into contact with various Marxist groups. He went on to work for a city lawyer but his main activity was revolutionary; After settling in Saint Petersburg, he came into contact with a Marxist organization at the Technological Institute, an environment in which he would spend the rest of his life.

In 1894, he wrote On the so-called question of markets. Having become one of the leading leaders in the city's Social Democratic circles thanks to his energy and erudition, he spent the next two years improving his organization in cooperation with other activists such as Martov. In the capital, in February 1894, he met his future wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, also a member of underground socialist groups. Thanks to her, Lenin came into contact with workers in the capital, since the circles in which he originally carried out his activity were mainly made up of intellectuals. to learn about the life of the workers to facilitate their work of revolutionary agitation and propaganda among the proletariat. His main activity was, however, literary, both in writings addressed to them and to the Russian intelligentsia.

In 1894, he moved to Moscow, where he continued his relationship with Marxist and worker circles, and continued to work theoretically against the ideas of the naródniki or populists. The attack on the populists occupies the bulk of his work in the first half of the 1890s. Against them he writes his works Who are the "friends of the people" and how they fight against the Social Democrats (1894) —polemic against the Social Revolutionaries and in defense of Marxist Social Democracy— and The economic content of populism and its critique in Mr. Struve's book (1894-1895), written together with other authors in collaboration with Piotr Struve. In these years in Saint Petersburg, he adopted the core of his political thought, which remained fundamentally unchanged for the rest of his life. For Lenin, the transformation of empire into a socialist society would be achieved through the activity of the proletariat, whose historical mission consisted of being the vanguard of the people, ending autocracy and imposing a democratic system that was to ensure popular state power that, over time, would transform society into a socialist one. The engine of these changes was It was to be the chain inspiration: the party was to inspire the proletariat in its action, which, in turn, would inspire the entire Russian people, which, finally, would inspire the world in the great transformation.

Between May and September 1895, he made his first trip abroad; his goal was to come into contact with and learn from the great figures of European social democracy. He first visited the "father" of Russian Marxism, Gueorgui Plekhanov, exiled in Switzerland, and the rest of the founders of the Group for the Emancipation of Labor, one of the first Russian Marxist organizations. Plekhanov recommended him to Wilhelm Liebknecht, one of the main leaders of the German SPD; he later visited Karl Marx's son-in-law, Paul Lafargue, in Paris, before passing through Berlin and returning to Russia on September 19.

Exile in Siberia

In the early 1890s, Marxists adopted a strategy of mass agitation aimed at raising workers' consciousness by organizing labor struggles. After Lenin's return from his trip to Western Europe, at the end of 1895 Vladimir Ulyanov and Yuli Martov (author together with Arkady Kremer of the booklet About Unrest of that same year) founded the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class, an organization that was dismantled almost immediately with the arrest of its leaders on the night of December 20, accused of social democratic propaganda among the workers of the capital. After more than a year in prison, he was exiled between 1897 and 1900 to Siberia, although he was allowed to choose his destination for health reasons and chose the village of Shúshenskoye, in the Minusinsk region south of Krasnoyarsk. The three years of exile, which he served in full, they proved productive personally, professionally, and politically. There he was married on July 10jul./ July 22, 1898greg. with Nadezhda (Nadia) Krúpskaya, a necessary marriage for her —also condemned to internal exile—could accompany him and should have been celebrated by the church. He also dedicated this time to writing his voluminous work The Development of Capitalism in Russia (1899). For Lenin, the extension of capitalism in the empire destroyed the old unity of the peasantry, increasingly divided into a dispossessed majority—a rural proletariat—and a minority of well-to-do peasants; both, however, were interested in opposing autocracy and bringing about a democratic revolution. Thus, the growth of capitalism in Russia was creating an ever-widening opposition, in which the peasants were united, in a vanguard role, the urban proletariat.

Politically, he developed his ambitious plan to unite the underground socialist organizations into a single party, an objective that he reflected in What to do? (1902) and in which he systematized the experiences of Russian activists in recent years to try to import the model of the German SPD (worker mobilization through party campaigns) into the repressive atmosphere of tsarist absolutism. This new clandestine party had to avoid police persecution and, at the same time, maintain its ties with the world The main link between the party and the workers' sympathizers would be a new national newspaper, which would also serve as a coordination instrument for the dispersed Russian social-democratic groups. The centralized party project proposed in ¿ What to do? until the Second Congress it had the support of the rest of the Iskra editorial board, who also considered it a necessary condition for the proletariat to obtain a leading role in the future bourgeois revolution.

His main ideological concern during exile was the rise of economism, a current influenced by the revisionism of Eduard Bernstein and the work of other social-democratic theorists such as Karl Kautsky, who defended the need to improve the conditions of workers within the capitalist system by peaceful means. These ideas began to be followed in Russia by Marxists such as Ekaterina Kuskova or Piotr Struve and, partly as a reaction to this, Lenin and Martov founded in 1900 the newspaper Iskra (The Spark), published in Munich, London and Geneva, with the aim of defending the political action of a centralized party that, in order to overthrow the Tsarist regime, considered that it could not follow the tactics of the German Social Democrats. This need for discipline and cohesion he set it out in more detail in the essay, explicitly inspired by Chernyshevski, What to do? (1902).

Iskra, the economists and the organization of the new social democratic party

While Lenin remained in Siberian exile, the socialist movement grew in Russia and in March 1898 the First Congress of the POSDR was held; the police detained all its participants and it was not possible to create a central institution to coordinate the various groups, but they began to feel part of a national organization. Eager to participate in the organization of the new party, when it ended in 1899 he he met Yuli Martov and Aleksandr Potresov and the three went into illegal exile in 1900. After meeting members of the Group for the Emancipation of Labor in Geneva, the three settled in Munich. After some friction among the Russian veterans in Geneva and the newcomers, the six founded the new newspaper that Lenin had planned during his exile: Iskra, which appeared in December. The publication, smuggled into Russia through various channels and with news from the Empire, it became the center of activity for Lenin, who not only wrote for the newspaper, but coordinated its distribution, collected information, or commissioned articles from other writers. In April 1902 and for a year, he moved to London when the German publishers decided to stop printing the publication, which they considered a risk. The newspaper also served as the germ of party unity, uniting the various Russian committees into an organ central office —the newspaper—, creating at the same time with its distribution network the base of an organization of professional revolutionaries skilled in clandestine tactics and facilitating the program unity of the committees.

Lenin considered that the economists idealized the current situation, which he considered primitive and with an amateur organization and advocated forming a strong, organized and disciplined one with a solid theoretical base. He justified his defense of a clandestine organization of professional revolutionaries by autocratic conditions in Russia, which did not allow for open agitation. In his opinion, the Economists incorrectly yielded to the primitive level of political consciousness of the masses instead of pushing them towards revolutionary positions. He was also opposed to admitting the sympathizers in the organization—though not in the general movement—because he argued that this would only facilitate the infiltration of the Tsarist police into it. Justified at the time by the autocratic conditions of Tsarist Russia, centralization, and secrecy as characteristics of the party clandestine were perpetuated once the monarchy had disappeared and the conditions is changed.

In April 1903, Lenin and Krupskaya reluctantly moved from London to Geneva at the request of the other Iskra editors, who wanted the group to reside in the same city.

Objection abroad and the split of the party

This conception of Lenin's led to the important split in 1903 during the Second Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, held between Brussels and London in August. Against Martov's theses, who defended the need for a mass party On a broad basis including sympathizers, Lenin wanted to admit as militants only professional revolutionaries integrated into a centralized leadership. Although Lenin's proposal was rejected by twenty-eight votes to twenty-three, the subsequent withdrawal of the five Bund delegates and two economists from then on he was granted a slight majority in the following matters dealt with in the congress. From that moment the division of the party was consolidated into two factions, the Bolshevik ("majority") faithful to Lenin's theses and with twenty-four votes in the last votes of the congress, and the Menshevik ("minority"), with twenty. Although the congress served to finally create some organizations for the party and to agree on a common program and tactics for the various committees that comprise it, the unexpected disagreements between the editors of Iskra (partly personal quarrels and desires to obtain positions in central organizations, but also tactical disagreements) frustrated the unification of the party and gave rise to the division (which gradually grew) between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks. At the congress and for a short period afterwards, Lenin had the support of Plekhanov. He warned that such a centralized and authoritarian policy was in danger of ending in a dictatorship and, in fact, the first thing Lenin did was remove the Mensheviks Pavel Axelrod, Aleksandr Potresov and Vera Zasulich from the editorial board of Iskra, which also led to the departure of Martov in solidarity with them. Lenin, in an attitude that he repeated later, broke relations with him, very close until then, due to their differences. political heritage. For Lenin, the obedience of the local organizations of the party to the leadership (the "centralist democracy") prevented the lack of coordination of the party (the fact that each local organization chose which directives to follow and which not) and the discipline of the members of the party avoided the growth of revisionist or economistic currents that could divert it from its revolutionary objective. In practice, it was capable of violating this rule of submission to the decisions of the party leadership —democratically elected— when these favored its members. political adversaries, preferring then the split of his supporters to the acceptance of rival positions. Extremely harsh with his adversaries and ruthless in defending his positions during the sessions, the Lenin of the congress was implacable and Machiavellian according to his critics, determined and defender of the correct tactics according to his followers. The break with Martov and his acceptance of and a split in the party revealed their willingness to make whatever sacrifices they deemed necessary to achieve their political ends. Extremely reluctant to give in to positions he did not share and to work under the leadership of another, he preferred to maintain a group of loyal supporters though this was scarce.

In May 1903, Lenin reluctantly returned to Geneva where, however, he once again combined his enjoyment of nature with the journalistic activities and political analysis that characterized his years in exile. He wrote a large number of articles, aimed mainly at the intelligentsia and with a not very subtle style of argumentation, often repetitive, for the various publications in which he participated during his long exile (among them Iskra, Vperiod or Proletarii). in nature. The family, always very close, and a changing circle of friends —modified according to the political alliances of the moment— supported Lenin during this period of hard political confrontations in the party. During these years, the obj Lenin's main objective that led to disagreements with his adversaries —in addition to the personal quarrels that also abounded— was his fear that any ideological concession to a position that he considered erroneous could end up undermining the revolutionary spirit of the party and converting it to the doctrine revisionist, which he rejected. Lenin gradually adopted an increasingly radical and minority position in the organization. His refusal to give in to what he believed to be non-negotiable and correct principles separated him more and more from the rest of the party members; what his few supporters saw as decisiveness and clarity of principle seemed to his adversaries dogmatism and intolerance. Little by little, Lenin created the nucleus of a centralized party of adherents in which he would have a decisive influence. The continuous disputes brought unpleasant consequences: illness —which appeared especially in moments of tension—, growing intolerance towards opponents and breaking with former colleagues due to ideological differences, with which he compromised less and less. His defense of the need for a disciplined party appeared in a series of works published at the end of 1903 and beginning of 1904. If during the congress Lenin had been the most prominent leader, by the end of the year he found himself isolated and on bad terms with his former co-publishers of Iskra, of the one who had resigned. In November he had broken his previous alliance with Plekhanov —willing to negotiate with the other currents, an attitude that he rejected— and resigned from Iskra, although the same month he joined the party's central committee. This, however, was a minor victory, since the Mensheviks controlled Iskra, an instrument key to dominating the party.

Although Lenin was essentially isolated from the rest of the party and European socialist figures in late 1903 and in 1904 — in the middle of this year he lost control of the central committee, made up mainly of Bolshevik supporters of the agreement with the Mensheviks and opposed to his intransigence that he considered in principle—and lacked a publication in which to present his ideas, his intransigence with what he considered opportunism from his adversaries began to attract a new generation of socialists who revived the faction. A notable part of the party's activists in Russia continued to see him as their mouthpiece; the Bolshevik faction eventually emerged from the organization of Lenin's supporters in Russia. The main members of this new generation were the brothers-in-law Anatoli Lunacharsky and Aleksandr Bogdanov. who, in turn, served as a contact with the second most famous Russian writer of the time, Maxim Gorky. This became an impor Much financial support for the Bolsheviks thanks to their patrons. The differences between Lenin and these new collaborators, however, ended up turning into an open confrontation, especially after the failed revolution of 1905.

According to Axelrod himself, he was the "idol" of Russian party activists. This year, Lenin became fully involved in intra-party disputes, leaving the imminent Russian revolution in the background. Even after the outbreak At the end of the revolution, he concentrated mainly on holding a new congress that would give control of the party to the Bolsheviks. The Third Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, boycotted by the Mensheviks, was held in London in April 1905 and was held in London. focused on the advisability of an armed insurrection in Russia.

Personal and political characteristics

Extremely active and intellectually original, Lenin displayed a combination of great ability to analyze certain aspects of a question with an inability to grasp the overall situation, a dogmatic rigidity which, coupled with self-confidence, gave rise to to a polemical style of dealing with those who disagreed with his opinions. His relationship with those around him also became pragmatic: according to his critics, Lenin approached those who were useful to him for his political purposes; for his followers, it was part of a messianic feeling that they admired, part of the rectitude of his convictions that could lead him to distance himself from those he considered wrong despite his previous closeness. The extremism of his positions, the ferocity with his His adversaries and his intransigence with dissents polarized reactions towards him: either total rejection or quasi-adoration. He poorly tolerated opposition, which he used to consider not only wrong, but often malevolent.

Throughout his career, a mixture of a scholar given to controversy and a radical politician devoted to his revolutionary ideal, he had the support of a close family circle (especially that of his mother and his sisters, as well as his wife) and of friends. If during his long exiles the intellectual part dominated the short periods of active politics in congresses and meetings —often followed by seasons of rest and exercise—, after the seizure of power the balance was definitively reversed until his gradual incapacitation from 1921.

The Revolution of 1905

The socialist parties had little influence in the unleashing of the 1905 revolution, they were still very weak, the internal militancy was scarce (some forty thousand members between Mensheviks and Bolsheviks for fifty thousand Socialist-Revolutionaries in November 1906) and almost all their leaders were in exile. Despite Lenin's interest in the revolution, he had remained in Geneva until the grant of an amnesty accompanying the October Manifesto allowed him to return safely to Russia on November 8 Jul./ November 21greg..

During the first ten months of the revolution, he wrote various articles on the situation of the empire, but the disputes in the party continued to have priority. To try to settle the disputes, he convened, as he had repeatedly demanded but in vain, a new party congress—the third—that was held in London between April 25 and May 12, which was ultimately attended only by his supporters. The congress gave control of the central party organs and the new official newspaper to Lenin and his followers, but he did not obtain the support of the International Socialist Bureau and had to be conciliatory with his adversaries in the party; the October Manifesto reinforced the convenience of unity in the organization in the face of the situation in Russia.

Lenin, who since Bloody Sunday had been sending instructions from Geneva to organize riots, only returned in November with the intention of organizing an armed revolt. In a series of articles written throughout the year, he made it clear his distrust of the Russian bourgeoisie and his conviction that the imminent bourgeois revolution would not be carried out by the bourgeoisie, but by an alliance between the urban proletariat and the peasantry. The following month he had gone into hiding, bothered by police surveillance. He did not play a notable active role in the events of the day, did not join the Saint Petersburg Soviet, and although he supported the Moscow uprising, his contribution was minimal.. Although he made some public appearance, his main activity was theoretical. He continued to dedicate himself mainly to the reorganization of the party. Having arrived in Russia after the mo Critical moment of the revolution, his calls for uprising were unsuccessful; by then the tsarist government was retaking control of events.

During 1905 and 1906, along with other socialist theorists, Lenin studied the possible evolution of the revolution in Russia in various writings that were not published until after his death. Convinced that only through civil strife first with the autocracy and later with the bourgeoisie the socialist revolution would triumph, he argued that this would be possible only if the Russian proletariat, abandoned by the peasant middle classes in the last phase of the conflict, had the support of the European proletariat. Socialist revolution in Russia, a backward country, was only possible if it had previously triumphed in the most advanced countries of Western Europe; then the European proletariat would come to the aid of the Russian who had been the origin of the chain revolutions with his bourgeois revolution in Russia. In his analysis of the nineteenth-century European revolutions, he emphasized the importance of armed confrontation and the need for the proletariat to show itself merciless to its class enemies. He later rejected moral criticism of the armed activities of his supporters during the subsequent reactionary period that he considered inappropriate in a situation he described as civil war. At the same time (1908), Lenin exposed the need for the State, immersed in civil war, to take the form of a dictatorship based on unlimited use of force, not on laws.

The Menshevik-dominated St. Petersburg Soviet, led by Trotsky, began a wave of strikes, with the result that on December 3 all its leaders were arrested. In response, the Moscow Social Democrats declared a general strike and distributed weapons to the workers. There they were actively aided by Maxim Gorky, who had met Lenin in 1902 and had become close to the Bolsheviks after Bloody Sunday, but with the arrival of army reinforcements around mid-December the insurgents were crushed. Trotsky was imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress, while Gorky and Lenin fled to Finland, from where Gorky went to the United States and Lenin returned to Switzerland. Increased reaction in Russia and greater political freedom in Finland, made him decide to leave Saint Petersburg and settle there. During his period in Finland, from March 1906 until his return to Western Europe in December 1907, he made several trips both to Saint Petersburg and Moscow, as well as to various foreign cities (Stockholm, Copenhagen, London —to attend the fifth party congress— or Stuttgart, etc), generally to attend party meetings. His main activity in this period was attending different party conferences and congresses in which decisions were made his position on various issues. Throughout 1906 he maintained his support for the armed insurrection, which was less and less likely, at the same time that he changed his opinion about the advisability of pa participate in the Duma: he opposed participating in the first but defended participation in the second, although he rejected pacts with the liberal deputies. As the revolution progressed, he gradually abandoned his defense of an armed uprising to concentrate on the usefulness of the new Parliament as an instrument of propaganda for the socialist movement; to this end, he advocated participation in the third Duma, elected by a more restricted electorate than the previous ones.In the summer and fall of 1907, he waned his interest in the situation in Russia and returned to focusing on European events.; the confiscation of a selection of his works by the police decided him to leave the empire at the end of the year, fearing arrest, he left for a new ten-year exile.

Meanwhile, attempts to reunify the party in various congresses continued. advocated by the Bolsheviks, he had a Menshevik majority. In the fifth (1907), on the contrary, his supporters had a majority. By then the differences between the two currents had become so accentuated that these attempts at reunification failed.

The period of reaction, exile and new disputes

Analysis of the failed revolution and preparation for the next one

After the failure of the 1905 Revolution, Lenin argued that the task of social democrats was to prepare for a new revolution that would end autocracy and establish a provisional government of workers and peasants. Only this type of government (the " revolutionary democratic dictatorship of workers and peasants") could, in his opinion, establish a democratic republic and defeat the forces of the counterrevolution. To achieve this objective, he defended a strategy based on two premises: the maintenance of the urban proletariat as the vanguard of the revolution and the spread of the socialist movement despite government repression; for Lenin, these two tactics had led to the first revolution and would serve to trigger the second.

Return to theory and the life of an émigré

He returned to Geneva in January 1908, but the events of the failed revolution made exile life less and less tolerable. While the party in Russia suffered a deep crisis caused by official persecution, worker and intellectual indifference after During a period of intense support, a lack of funds and the activity of police infiltrators who encouraged the dissolution of the cells or the arrest of their dwindling members, Lenin moved from Geneva to Paris in December 1908, where he continued with his usual activity. as a party intellectual: immersed in the disputes between factions or preparing motions for the various congresses. These post-revolutionary years were for him mainly a series of endless disputes with the various currents of the party that made sense due to the need for it to adopt the positions and objectives that he considered correct. Despite the move to Paris, the situation did not improve; the return to inactivity and the intensification of disputes in the party discouraged the exiles. Lenin and Krupskaya resumed their life of disputes in the party, continuous trips to different meetings, observation of the international situation and enjoyment of nature.

Break in the Bolshevik ranks

In the reactionary climate of the years following the failed revolution of 1905, a new philosophy, empiriocriticism, began to exert influence among Russian and German socialist circles. Its main representatives were Mach and Avenarius. It was a supposedly Marxist philosophy, which sought to abandon materialism, drawing inspiration from the recent crisis in physics and from philosophies based on the scientific method, such as positivism. Lenin's confrontation with this philosophy, which he described as idealist and the successor to Berkeleism, materialized in one of his most important philosophical works: Materialism and Empirio-Criticism (1909). In this he unleashed a fierce attack against Aleksandr Bogdanov and the German precursors of monism, while criticizing idealism and the affirmation of the impossibility of knowledge beyond one's own consciousness. At a tense meeting of Proletarii held in Paris between on June 21 and 30, Lenin's position was victorious, Bogdanov's supporters went into opposition and he was expelled from the editorial board; again, Lenin eliminated from the party those he considered heterodox, broke relations with the main intellectuals of the party and returned to isolation within the organization.The failure of the revolution also ended with the temporary rapprochement of Bolsheviks and Mensheviks; once the reaction was established, disagreements quickly resurfaced. In a letter to Zinoviev written at this time, Lenin expressed his opposition to the Mensheviks, Bogdanovists and Trotsky, whom he considered worse than the other two factions, despite attempts to this for cooperating with him. During the years before the World War, disputes abounded between Lenin and these three groups, which alternated successive ruptures with ephemeral rapprochements. With Plekhanov, whom he still hoped to attract, however, he maintained a more cordial attitude. Increasingly, Lenin considered that the unification of the party should not be carried out through concessions to the other currents, but by their acceptance of the positions he held. defeat of the revolution in Russia, which affected all the currents of the party, instead of trying to reunify it through the cession, Lenin dedicated himself to accentuating the differences, trying to make the p Bogdanov's supporters were not recognized by the German socialists—who managed the party's funds in the face of the constant quarrels of its members—as legitimate representatives of the POSDR and to punish "liquidationists" and "reversalists" in their writings.

Break with the Mensheviks

In the late summer of 1910, he attended the International Socialist Congress in Copenhagen; he took advantage of his visit to the Baltic to see his mother in Stockholm, the last time he was able to do so before her death in 1916. That same year, he became friends with Inessa Armand, a determined Bolshevik, who, according to most authors, became a temporarily in her lover, which did not prevent her friendship with Krupskaya or end her marriage. Neither this episode, nor the frequent trips and periods of rest from political activities alleviated the growing boredom of life abroad, especially when Starting in 1912 with the massacre of the Lena mines, opposition to the autocracy in Russia began to resurface and with it the hope of the exiled revolutionaries. The new wave of protests and strikes increased worker militancy; This mainly favored the Bolsheviks, who began to have majorities in unions and cooperatives. Faced with the impossibility of returning to Russia yet but wanting to follow events more closely, he moved from Paris to Kraków accompanied by Zinoviev in 1912, shortly after the conference in Prague, where his spirits improved due to the similarity of the atmosphere with the Russian one and the distance from the emigrant community and their continuous disputes; there he felt only "semi-exiled". During his stay in Austria-Hungary, Lenin dedicated himself to analyzing both the situation in Russia, which he believed was going to lead to a new revolutionary period, and the international one, characterized by increasing tensions. that led to war, in his opinion a consequence of imperialism.

The differences between factions were already so great that in 1911 Lenin advocated the separation into two parties. He wanted to expel the Menshevik liquidationists from the formation. After various maneuvers, the Prague conference of January 1912 met. It was one of the main milestones in the formation of a Bolshevik party separate from the other Social Democratic factions; eighteen Bolsheviks and two Mensheviks attended and Lenin controlled it. He confirmed the party's split with the formation of a new central committee (including Lenin, Zinoviev and fourteen Bolshevik activists from Russia), although it did not serve to end the disputes between currents or to obtain the party funds guarded by the International Socialist Bureau. It had important consequences: Lenin entered the central committee and elected him as the party's representative to the Bureau, Pravda was founded on May 5 —to which Lenin contributed a large number of art icles—and the majority of the leaders who later collaborated with him during the 1917 Revolution gathered around him., published an article in which he made it clear that unity could only be achieved if the other factions accepted his conditions. Rejecting attempts by European socialists at reconciliation between the factions, it was probably only the outbreak of World War I that freed him. of condemnation of those for their total opposition to reconcile with the Mensheviks, a position that, however, had increasing support in Russia. Again, the second decade of his political career ended in a similar way to the first: with its almost total isolation from the émigrés but with notable support among activists in Russia. Lenin planned a sixth party congress for the summer of 1914 that would have consummated the division ion with the Mensheviks started at the 1912 conference, despite attempts at reconciliation by European socialists.

World War I

Brief arrest and return to Switzerland

At the beginning of the summer of 1914, he considered that the war could reduce his work by isolating him from Russia but he did not expect the consequences that the war brought for European socialism. When the world war broke out on August 4, 1914, Lenin he was in his summer retreat in the mountains, in Poronin at the foot of the Tatra Mountains, where he had spent the previous summers since his installation in Austro-Hungarian Galicia. The next day, after weeks of protests by the various socialist parties against the war, received incredulous news that German Socialist deputies had approved war credits in the Reichstag. Considered suspected of espionage, police searched his rented cabin on 7 August, seized his notes, and arrested him the next day. He achieved his release on the 19th thanks to the intercession of the socialist leader Victor Adler before the very Austrian Minister of the Interior, to whom he assured Lenin's hostility to the Tsar After his release, he received another deep impression, that of the Russian socialists who were enlisting in the French Army; shortly thereafter he left by train for Bern in neutral Switzerland, arriving on 5 September after passing through Vienna. Accepting help from Adler, whom Lenin routinely criticized as "opportunistic", was characteristic of Lenin: during his career he took advantage of the sentimentality of his adversaries if he thought it necessary; for him, the advance of what he believed to be the true revolution was his moral reference.

Rupture of the socialist movement due to the world war

If the World War ended the pre-war European order, it also destroyed the hitherto known socialist movement. The conflict disrupted the national unity of the socialist parties—generally divided among a majority that supported participation in the war and an opposing minority—and internationalist solidarity between the formations of the different countries. The Bolsheviks were the only left-wing party that, almost unanimously, opposed World War I from the beginning. For its leaders, the support of the German Social Democrats for the war projects of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany was a real shock. Nikolai Bukharin called it "betrayal", Aleksandra Kolontai had to leave the Reichstag when the military budget was approved, and Lenin, who was in Switzerland like Trotsky, initially refused to believe it. The German action sparked a process in a chain in which the majority of the socialists of the different countries that participated in the conflict supported their respective governments, instead of opposing the war. The internationalist minorities opposed to the war proved incapable of forming an alliance since that united them little more than the rejection of the conflict.

Rejection of the world war and defense of the civil war

The same day he arrived in Bern, he met with some Bolsheviks and raised the need to write a theses to face the world war. He exposed the need to turn the imperialist world war into a civil war: the world war should serve to accelerate the revolutionary process both in each country and internationally. The majority attitude of European socialists in support of their respective governments seemed to him a sign of opportunism, a betrayal of revolutionary socialism. According to Lenin, his position was not a change With respect to the one before the conflict, it was the majority of the socialist leaders who had changed their attitude with the war. A minority even among the socialists opposed to the war, he tried to form a leftist current within them that rejected peace as a priority He held that only revolution, which could temporarily lead to an increase in fighting rather than a reduction, could end with the capitalist root of war.

The war caused the progressive approach of many Mensheviks, such as Kolontái or Trotsky, to Lenin's positions. His party, like the Social Revolutionary Party, had been divided between Plekhanov's "defensist" current, which considered it a priority to avoid Russia's military defeat, and another "internationalist" current with pacifist ideas led by Martov, who in principle was Trotsky, the majority, also joined. Lenin, however, went further and aspired to take advantage of the war to provoke worker uprisings against their respective governments or even authentic civil wars. For Lenin, the world war was an imperialist conflict, a natural consequence of the last capitalist stage and of the desire of the different powers for supremacy, from which the proletariat did not obtain any advantage, which had to be unambiguously denounced and turned into a fight against the bourgeoisie to eliminate it from power. In his opinion, the pacifists were wrong and the civil war was necessary to overthrow the bourgeois power.

Analysis of the world war: the clash of imperialist blocs

His analysis was greatly influenced by the work Financial Capital by the Austro-Hungarian Rudolf Hilferding, with which he shared the rise of international oligopolistic companies that fostered profit-seeking imperialism, caused the race in their mutual competition and led to world war. Lenin also shared with Hilferding his conviction that imperialism was the cause of improving the living conditions of certain working classes in the most technologically advanced countries; for him, this change explained the appearance of revisionist currents within socialism. Following Hobson and unlike Hilferding, Lenin also argued that the system was in its final crisis. According to Lenin, the conflict was nothing more than a clash between two capitalist blocs, the German and the Franco-British, who were fighting for control of international markets and seeking the ruin of their adversary; Russia was nothing more than a pawn of the second block. After the war, it used the peace treaties of Brest-Litovsk and Versailles to justify this analysis. The internalization of capitalism, indicated by Hilferding, Bukharin or Luxembourg, also served it well. to justify the possibility of a socialist revolution in Russia: since capitalism is no longer national but international, the development —a necessary condition for the emergence of socialism according to Marxist analysis— of the country was not crucial for the beginning of the revolution, provided that then it would spread to the more developed countries; the revolution could take place in backward Russia, Lenin thought, if the more developed nations then joined it. The framework of analysis went from being national to international.

According to Lenin, the powers would not stop the confrontation until they had achieved the defeat of their rivals that would grant them primacy. This would lead to a polarization of the factions and, within each country, to the growing search by the proletariat of organizations opposed to the prolongation of the conflict. This would eventually lead to the bourgeois revolution in Russia and to the socialist one in the most advanced countries of Western Europe. Despite the fact that this position was very minority at the beginning of the war, it was not he hesitated to support it throughout the war period. He was convinced that, with the progress of the fighting, the majority of the European proletariat would end up supporting it.

Break with the defenders

He harshly denounced those socialists who supported their governments in the contest, since he considered that they deceived the workers and led them to defend the interests of the bourgeoisie. He also disagreed with the majority of socialists opposed to the contest in the possibility and convenience of reviving the Socialist Second International in the company of those who had supported their governments in the conflict. At the beginning of 1916, he moved to Zurich to use its library for the writing of Imperialism, phase superior of capitalism , a work critical of the warlike Kautsky; the move, initially temporary, became permanent.

He came to consider a Russian defeat preferable because he foresaw it would hasten the disintegration of the Tsarist Empire, for which he also proposed stimulating internal nationalist movements. Although Bukharin, Kolontai, Trotsky and other leaders, such as Lunacharsky or Antonov-Ovseyenko, disagreed on these substantive issues, what they saw as inactivity and passivity in the Menshevik strategy caused them to come closer to Lenin's more active tactics and, towards the end of the war in 1917, they were all on his side.

Activity in isolation

While the contenders bled to death in the great battles of the conflict, Lenin lived as a scholar and writer in neutral Switzerland, virtually cut off from Russia and the rest of the continent by the war. Despite difficulties, he resumed the publication of The Social Democrat and devoted himself again to philosophical study. His review of certain philosophers, such as Aristotle or Hegel, convinced him of the importance of dialectic to understand the works of Marx and led him to affirm that his followers, neglecting it, had failed to interpret them correctly. His conclusions, however, were not then published.

He participated in the Zimmerwald Conference in September 1915 but, despite the fact that the assembled Socialists were overwhelmingly anti-war, his position was outnumbered, as was the case at the subsequent Kienthal Conference in April 1916.

Also during the war, Krupskaya and Lenin suffered significant personal losses: on March 20, 1915, her mother died, her usual companion in marriage, and on July 25, 1916, Lenin's did. Although Lenin maintained apparently impassive upon receiving the news, he visited her grave hours after reaching Petrograd in April 1917.

Lenin and the 1917 revolution

After the outbreak of the First World War, with the shock that the support of the German Social Democracy caused to the Bolsheviks, the situation made him a key figure when the evolution of the war was openly unfavorable for Russia.

Despite expecting that the war would soon lead to revolution in Europe, the February Revolution and the fall of the monarchy in Russia were unexpected for Lenin, as for many other observers of the day, both in Russia and abroad. The change in Russia could be the beginning of a world revolution which, in his opinion expressed shortly before, could take decades to end world capitalism. The life of socialist libraries, publications and conferences gave way abruptly to a desire for emigrants to return to Russia as soon as possible.

Letters from afar and April Theses

On March 15, 1917, he received news of the February Revolution, the abdication of the Tsar, the formation of the Provisional Government and the Petrograd Soviet. Lenin, who had been in exile for seventeen years except for a brief interval of six months between In 1905 and 1906, when the February Revolution occurred, he was in Zurich and wanted to return to Russia as soon as possible, something extremely complicated in the midst of the First World War.

Faced with British opposition, even Trotsky and Bukharin were being held in England upon their return from the United States, and it was Martov who proposed an exchange of exiles in Switzerland in exchange for other German prisoners. France was also opposed to the passage of internationalists through its territory and clandestine passage through Germany was soon ruled out. As the Bolsheviks were opposed to the war, the German government, which was already financing their activities, immediately agreed. Consequently, the Provisional Government was suspicious and the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Pavel Miliukov, was openly opposed in view of Lenin's "defeatist" stance and upon his return to Russia. Despite being aware that they could be accused of collaboration with the Germans, as was the case later, thirty-two émigrés requested the mediation of the Swiss socialist Fritz Platten, who negotiated with the German ambassador their transfer through the empire to Sweden, from where they would go to Finland before reaching Petrograd. Most of the Russian émigrés living in Switzerland ended up accepting the German offer to return to Russia through its territory. On March 27Jul./ April 9greg., Lenin began the trip on a "sealed" train, which the Germans let circulate without inspections of any kind and arrived at the Station of Petrograd Finland on the night of April 3Jul./ April 16greg.. The sealed train had left Gottmadingen on the German-Swiss border to Sassnitz where the thirty of émigrés took a ferry to Sweden. The fact that the Germans could not board the train and contact the Russians was a condition that Lenin hoped would reduce the negative impact of the trip on his image; an enemy government allowed passage (as he had succeeded in Austria-Hungary in 1914) to an enemy of the Russian Government. Immediately after his arrival in the capital, he ended the festive character of the reception with a speech in which he strongly criticized the Provisional Government and the attitude of the Soviet of Petrograd and which included the fundamental points of his April Theses.

In these, Lenin outlined a series of key concepts of his program for the interrevolutionary period: frontal rejection of revolutionary defencism, refusal to support the Provisional Government and decision to denounce its actions, the need to transfer state power to the Soviets, the demand creation of a non-parliamentary Soviet republic or the consideration that power should pass to the workers and poor peasants in a second revolution. The April Theses were, in reality, almost a repetition of the already raised in October 1915: rejection of the government of "revolutionary chauvinists" determined to continue the war, support for the transfer of power to the soviets, defense of the peasant occupation of land or use of diplomacy to turn the world war into a war Once again, he reiterated his conviction that the democratic revolution in Russia would facilitate a socialist one in Europe, a fundamental condition for Russia to be able to pass well to socialism. The political leaders of the capital generally rejected the theses, but these allowed the emergence of a strong current of leftist opposition, both to the Government and to the positions of the Petrograd Soviet, led by Lenin. Lenin rejected likewise any rapprochement with the rest of the socialist formations since he considered the total independence of the party essential for the fight that should lead to the establishment of the communist system and that, in his opinion, the other parties could get in the way. This transition would entail a civil confrontation, necessary for the confrontation between classes and for the triumph of the proletariat over the exploiting classes worldwide.

At the party conference held between April 24Jul./ May 7greg. and April 29Jul./ May 12greg., managed to get him to accept the preparation of a new revolution, reject cooperation with non-socialist parties, criticize the government and the Petrograd Soviet, accentuate the division with the Mensheviks, demand immediate peace and the application of profound economic and social reforms, tighten relations with the bourgeois forces, even at the risk of provoking a civil war, and accepted the Russian revolution as the first in a series of European revolutions that were to end the war. By then, he had already won the support of most of the delegates from the Petrograd districts. The date of the new revolution, however, remained unfixed, partly to facilitate an agreement between the more moderate current and the m radical of the party. Although initially with little popular support and without political power, the attitude that Lenin managed to impose on the party made it the main beneficiary of the growing political, economic and social crisis, since it turned it into the opposition party par excellence. His radicalism gained support as the crisis escalated in the summer and autumn of 1917. In just a few weeks after his return to Russia and through an intense propaganda campaign in the organization, Lenin had managed to wrest the leadership of the party from the moderate current headed by Kamenev who advocated turning it into a peaceful opposition to the Government and aligning it with the most radical revolutionary demands of the population.

The following day Lenin presented his famous April Theses, with hardly any knowledge of the specific situation in Russian territory and at his own risk.

In these theses, Lenin addresses the following issues:

- Rejection of the imperialist war, subject to the interests of capital. These same interests make it impossible for a peace that is truly democratic, not imposed by force, and without annexations.

- In Russia it has gone from the first stage of the revolution (which gives power to the bourgeoisie) to the second stage, which must put that power into the hands of the proletariat and the poor peasants.

- Unmask the Provisional Government as a government of capitalists, and deny them all support.

- Recognition that the Party is in a minority in the soviets. It is therefore necessary to explain and spread its positions, from a critical minority.

- Reivindication not of a parliamentary republic, but of a republic of the soviets. Within which police, army and bureaucracy are abolished, without the remuneration of all officials ever exceeding the salary of a skilled worker.

- Land reform. Confiscation of landowners. Nationalization of all lands to be made available to the local Soviets.

- Fusion of banks in a single bank under the control of the soviets.

- Priority of the democratic control of the production and distribution by the soviets, before the immediate "implantation" of socialism.

- As tasks of the Party: (1) Celebration of a new Congress. (2) Modification of the program in relation to the position before imperialism and the state, and reform of the minimum program. (3) Change of the Party's denomination, which is to move from "social democrat" to that of Communist.

It was at this moment that Lenin found himself completely alone. The right wing of his party accuses him of anarchism, adventurism and calling for a civil war. The left wing appropriates the Theses to turn them into an immediate program to overthrow the provisional government. In reality, due to the circumstances in which they were pronounced and the subsequent attitude of Lenin himself (who allied himself with that right wing and against the leftists during the April Conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party), it seems more sensible to lean towards a less blunt interpretation. The Theses aim to put a medium-long-term program on the table, a political trajectory that must be followed during the following months.

The July Days and the clandestinity

Despite the tension in the capital, on June 29Jul./ July 12, 1917greg. he left it to rest for a few days in Neivola, a Finnish town about four hours by train from Petrograd. In April, Lenin had already appeared tired and had complained of headaches, perhaps the first symptoms of the cerebral arteriosclerosis that would end up killing him in 1924. The central committee had to face its greatest crisis, the July Days, without Lenin, which while resting in the dacha of his secretary Vladimir Bonch-Bruyevich. capital in a hurry on the morning of July 4thjul./ July 17, 1917greg., convened by the central committee, which had finally decided to support, albeit with great reluctance, the protests of the population, since it had not been able to put an end to them. Although it was favorable to the transfer of government power to the sov iets, was skeptical about the possibility of success of the protests, an attitude that was reflected in his statements to the protesters. After the failure of the attempt to end the provisional government, a period of repression broke out and the government ordered the Lenin's arrest, along with that of other party leaders. Most turned themselves in to the authorities, except Lenin and Zinoviev who, after considering turning themselves in, decided on July 8jul./ July 21, 1917greg. go underground. The next day they left the capital and settled in the home of a capital worker in Razliv, a village about 30 km from Petrograd, hiding in the barn. Despite some moments of tension due to the persecution by the authorities — each time less intense — the fugitives were able to enjoy a few weeks rest in the field that Lenin took advantage of to return to writing. His articles appeared again appear in the Bolshevik press on July 26Jul./ August 8, 1917greg. and resumed writing The State and the Revolution. Unsure even so close to the capital, he decided to move to Finland, where he had the cooperation of the Finnish Social Democrats, close to the Bolsheviks. Disguised As a worker, wigged and shaved, and later as a stoker, he arrived in Helsinki on August 10Jul./ August 23, 1917 greg.. In the city, he changed his residence several times, always sheltered by the local socialists, and dedicated himself to writing The State and the Revolution, from articles for the Bolshevik newspapers and from letters to the central committee.

Lenin took advantage of the months in exile to finish writing his important work The State and the Revolution, of which he had left a copy of the manuscript to Kamenev with orders to publish it if he did not return, which It had to lay the theoretical foundations regarding the seizure of state power, the transformation of the bourgeois state into a socialist state (essentially made up of the mass organs: soviets of workers, soldiers, etc.), and the extinction of this as a step progressive towards communism. After briefly hesitating about the advisability of forging a new state system based on soviets after the failure of the Conference, he returned to defend it in late summer and early fall. The goal was not to form a cabinet with ministers drawn from the capital's council, but to replace the Administration inherited from tsarism with a new one based on the soviets. The party became the main defender of the popular formula "all power for the soviets", which contained the desire for profound changes and was a symbol of change radicalism that it embodied, to both supporters and opponents. Along with other far-left groups such as anarchists, Internationalist Mensheviks, and Left Social Revolutionaries, the party grew in popular support throughout the late summer and early fall, while Lenin remained in hiding. Meanwhile, the Provisional Government and the moderate socialists, bent on the mit the violence in the cities and the countryside but without satisfying the desire for change of the population, they were weakening. For Lenin, the new coalition headed by Kérensky that emerged after the July Days was a Bonapartist dictatorship interested only in maintaining the order. The new government, in effect, resumed passivity regarding the agrarian problem prior to the July crisis. The failure of the Kornilov coup at the end of the summer favored mainly the Bolsheviks. For a growing proportion of the population, the defense of the moderate socialists in the coalition with the bourgeois forces did not favor more than the latter and was leading the country to ruin, an analysis defended by Lenin's party.

Since the end of September and having already ruled out cooperation with the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries —contemplated briefly during the Kornilov coup—, whom he considered traitors to Marxism and accomplices of the bourgeoisie, he began to vehemently demand the seizure of the power by the party through an armed uprising, convinced of the popular favor of the Bolsheviks, reflected in the victories in the autumn soviet elections. For Lenin, the weakness of the Government, the discredit of the supporters of the social coalition -bourgeois, the new Bolshevik majorities in the soviets, the instability in the countryside and the revolutionary situation in other belligerent countries made the need for an immediate insurrection imperative. Convinced that the opportunity to seize power was unique due to the situation in Russia and in Europe, he emphasized the need to prepare an immediate uprising, without waiting for the next congress of the soviets. The majority of the delegates to the congress seemed to support a coalition government of the socialist formations, which Lenin rejected. His attitude, already opposed to cooperation with other socialist groups, turned out to be a minority in the party leadership. The moderate opposition, Headed by Lev Kamenev and Grigori Zinoviev, and opposed to rising up against the government or isolating itself from the other socialist groups, it prevailed in the absence of Lenin, although the main position was Trotsky's intermediate: favorable to an anti-government uprising but not alone, but in the name of the Congress of Soviets. Contrary to expectations, Lenin decided to leave his Finnish refuge and return to the Russian capital to defend his positions. He hid in an apartment north of the Vyborg district of Petersburg, mostly pro-Bolshevik. Despite achieving the support of the central committee for the preparation of the uprising at the meeting on October 10ju l./ October 23rdgreg., the approved resolution did not set a date, it did not imply that it was to take place before the congress, as Lenin had advocated, nor were serious preparations made for it. In practice, the majority opted to link the seizure of power to the next Second Congress of Soviets, which was to be held two weeks later.

On his return, in October, the process begins that will culminate on November 7 (according to the Gregorian calendar) with the capture of the Winter Palace. His arrival at the Soviet headquarters in the capital on the night of October 24Jul./ November 6greg.—who was violating the orders of the central committee to remain in hiding and nearly got himself arrested by a patrol—along with perceived government weakness throughout the day accentuated the offensive nature of the actions of the Petrograd Soviet during the October Revolution. During the early hours of the morning, the Petrograd Soviet began to seize power before the imminent opening of the Congress of Soviets that same day, as Lenin had advocated throughout the autumn. Lenin delayed the opening of the Congress as long as possible in order to present before it the fait accompli of the overthrow of the Provisional Government. In the first session, he presented the proclamation of the overthrow and seizure of power by the Congress and the Soviets. session of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets (November 7-9). re of 1917), recently abandoned clandestinity the night before, presented the two decrees (on land ownership and on peace) that were to serve as the foundations for the new Government that emerged from the congress. The Decree on peace Although vague about the attitude of the new government in the event that its peace offer was rejected, it was essential to curry favor with the troops, fed up with the strife. The Decree on the land, which handed over the estates to the peasant soviets without compensating its former owners and it abolished land ownership, it was also essential to achieve peasant support for the new government, it obtained the support of the left Social Revolutionaries —on whose program it was based— and legalized a process that already was taking place in practice. Eventually, the congress approved the formation of a new government, the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom), chaired by Lenin and made up entirely of "commissaries" (m ministers) Bolsheviks.

Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom)

Bolshevik or coalition government and dissolution of the Constituent Assembly

Favorable of a coalition with the Left Social Revolutionaries as representatives of the peasantry but firmly opposed to an alliance with other socialist groups (a position with notable popular support due to the opposition to a coalition with the bourgeois forces), he succeeded in making the attempts fail. to form a grand coalition of all socialist parties, imposed by the railway union (Vikzhel) a few days later. He considered the negotiations, favored by the party's moderate current and ultimately failed, as a mere ploy to buy time in which to assert political control of Sovnarkom. Threatening to split the party, he won majority support from the central committee to ensure a largely Bolshevik government and the defeat of the more conciliatory current with the other socialist parties — for their part, intransigent in their demands during the negotiation. Determined to establish a one-party dictatorship a, had to act on behalf of the soviets despite the fact that real power resided in the party. Despite formally subordinating the Sovnarkom to the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, both to maintain the fiction of Soviet and non-Bolshevik power and to ensure the support of the left Social Revolutionaries —necessary after the seizure of power—, since this first crisis regarding the composition of the Government of November 1917, the former could in practice govern by decree.

He tried in vain to annul the elections to the Constituent Assembly, to which he had no intention of ceding his newly obtained power in the event of a Bolshevik electoral defeat; its celebration, however, appeased part of the opposition, convinced that they could remove the Bolsheviks from power in the Assembly. Despite his previous criticism of the provisional government for its delay in calling the assembly and for having stated that only the The Soviet government guaranteed their meeting, once the Bolshevik defeat in the elections became clear —in which they obtained around a quarter of the votes—, it launched a smear campaign and threats against the institution. In December it published a series of theses in which he affirmed the superiority of the Soviet Government over the Assembly, which he demanded that it limit itself to accepting the measures approved by it. Committed to holding the elections to the Constituent Assembly, he rejected any authority that was not the of the soviets, including that of the Assembly. Deprived of part of the popular support precisely because of the measures approved earlier by Lenin, which fulfilled part of the political expectations icas of the population, the Government dissolved the Assembly after the first session on January 6Jul./ January 19, 1918greg.. The forced dissolution, imposed when the Assembly refused to recognize the supreme authority of the Soviets and Lenin's government, culminated the process of political polarization that led to the war civilian.

Heading the Government

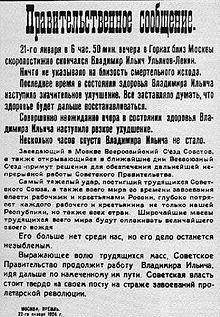

On March 12, 1918, Lenin, Krupskaya and the Soviet government moved to Moscow for reasons of military security and settled in rooms in the Moscow Kremlin, next to the government meeting room. It was the last move of Lenin, who only left Moscow to rest in dachas near the new capital. After his transfer to Moscow, a small mansion was made available to him in the nearby town of Gorki.

From daily night sessions at the beginning of the Petersburg period, the Sovnarkom chaired by Lenin began to meet less frequently —a couple of times a week—, especially after the creation of bodies such as the “Little Sovnarkom” or the Junta de Defensa a to whom part of the government decisions were delegated. The "Little Sovnarkom", in charge of minor matters delegated by the Sovnarkom, was controlled by Lenin, who closely followed what was dealt with here too, despite his intense activity in the Sovnarkom. The decisions of the body had the same authority as those of Sovnarkom if they were approved by the president of Sovnarkom—Lenin himself—without the need to obtain the latter's approval. At times, he used the prerogatives of "Little Sovnarkom" to impose an action contrary to what the Sovnarkom could approve or wanted to approve quickly, simply by sending him his preferences and signing them later as president of the Sovnarkom.