Late Modernity Period

The Late Modernity Period or Contemporary Age (in French and Spanish) is the name given to the historical period between the Declaration of Independence of the United States, the French Revolution or the Spanish-American Wars of Independence, and the present day. It comprises, if its beginning in the French Revolution is considered, of a total of 233 years, between 1789 and the present. In this period, humanity underwent a demographic transition, completed for the most advanced societies (the so-called first world) and still ongoing for the majority (underdeveloped and newly industrialized countries), which has taken its growth beyond the limits historically imposed by nature, achieving the generalization of the consumption of all kinds of products,

The events of this time have been marked by accelerated transformations in the economy, society and technology that have earned the name of the Industrial Revolution, while the pre-industrial society was destroyed and a class society presided over by a bourgeoisie was built. it saw the decline of its traditional antagonists (the privileged) and the birth and development of a new one (the labor movement), in the name of which different alternatives to capitalism were put forward. Even more spectacular were the political and ideological transformations (Liberal Revolution, nationalism, totalitarianism); as well as the mutations of the world political map and the greatest wars known to mankind.

Science and culture enter a period of extraordinary development and fertility; while contemporary art and contemporary literature (liberated by romanticism from academic restraints and open to an ever-widening public and market) have been subjected to the impact of the new mass media (both written and audiovisuals), which caused them a true identity crisis that began with impressionism and the avant-garde and has not yet been overcome.

In each of the main planes of historical evolution (economic, social and political), it can be questioned whether the Contemporary Age is an overcoming of the guiding forces of modernity or rather means the period in which they triumph and reach their full potential of development of the economic and social forces that were slowly developing during the Modern Age: capitalism and the bourgeoisie; and the political entities that did it in parallel: the nation and the State.

In the 19th century, these elements came together to form the historical social formation of the classical European liberal state, which emerged after the crisis of the Ancien Régime. The Ancien Régime had been undermined ideologically by the intellectual onslaught of the Enlightenment (L'Encyclopédie, 1751) to everything that is not justified in the light of reason no matter how much it is based on tradition, such as privileges contrary to equality (that of legal conditions, not socio-economic) or the moral economy contrary to freedom (the market one, the one advocated by Adam Smith - The Wealth of Nations, 1776). But despite the spectacular nature of the revolutions and the inspiration of their ideals of freedom, equality and fraternity (with the very significant addition of the term property), a perceptive observer like Lampedusa could understand them as the need for something to change so that business as usual: the New Regime was governed by a ruling class (not homogeneous, but very varied in composition) which, together with the old aristocracy, included for the first time the thriving bourgeoisie responsible for the accumulation of capital. This, after coming to power, went from revolutionary to conservative,aware of the precariousness of their situation at the top of a pyramid whose base was the great mass of proletarians, compartmentalized by the borders of national states of dimensions compatible with national markets that in turn controlled an external space available for their colonial expansion.

In the 20th century, this unstable balance began to break down, sometimes through violent cataclysms (beginning with the terrible years of the First World War, 1914-1918), and at other levels through gradual changes (for example, the economic, social and women's politics). On the one hand, in the most developed countries, the emergence of a powerful middle class, largely thanks to the development of the welfare state or social state (understood as a pactist concession to the challenge of the most radical expressions of the labor movement, or as a conviction of social reformism) tended to fill the abyss predicted by Marx and that should lead to the inevitable confrontation between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. On the other hand, capitalism was harshly combated, albeit with rather limited success, by itsclass enemies, facing each other: anarchism and socialism (divided in turn between communism and social democracy). In the field of economic science, the presuppositions of classical liberalism were overcome (neoclassical economics, Keynesianism -incentives for consumption and public investment to face the inability of the free market to respond to the 1929 crisis- or game theory -strategies of cooperation against the individualism of the invisible hand -). Liberal democracy was subjected during the interwar period to the double challenge of Stalinist and fascist totalitarianism (especially by the expansionism of Nazi Germany, which led to World War II).

As for the national states, after the spring of the peoples(denomination given to the 1848 revolution) and the period presided over by the German and Italian unification (1848-1871), became the predominant actor in international relations, in a process that became generalized with the fall of the great multinational empires (Spanish from 1808 to 1976, Portuguese from 1821 to 1975; Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian and Turkish in 1918, after their collapse in the First World War) and that of the colonial empires (British, French, Dutch and Belgian after the Second). Although many nations gained independence during the 19th and 20th centuries, they were not always viable, and many were plunged into terrible civil, religious or tribal conflicts, sometimes caused by the arbitrary fixing of borders, which reproduced those of the previous ones. colonial empires. In any case, the national states, after the Second World War, became increasingly less relevant actors on the political map, replaced by the politics of blocs led by the United States and the Soviet Union. The supranational integration of Europe (European Union) has not been successfully reproduced in other areas of the world, while international organizations, especially the UN, depend for their operation on the unsteady will of their components.

The disappearance of the communist bloc has given way to the current world of the 21st century, in which the traditional ruling forces witness the double challenge posed by both the trend towards globalization and the emergence or resurgence of all kinds of identities, personal or individual, collective or group, often competitive with each other (religious, sexual, age, national, cultural, ethnic, aesthetic,educational, sports, or generated by an attitude -pacifism, environmentalism, alter-globalization- or by any type of condition, including problems -disabilities, dysfunctions, consumption patterns-). In particular, consumption defines in such an important way the image that individuals and groups make of themselves that the term consumer society has become synonymous with contemporary society.

Modernity: rupture and continuity

The denomination «Contemporary Age» is a recent addition to the traditional historical periodization of Cristóbal Celarius, who used a tripartite division into Ancient Age, Middle Age and Modern Age; and it is due to the strong impact that the transformations after the French Revolution had on continental European historiography (specifically French, Spanish and Portuguese), which prompted them to propose a different name for what they understood as antagonistic structures: those of the Old Regime before and those of the New Regime after. However, this discontinuity does not seem so marked for the rest of the historians, such as the Anglo-Saxons who prefer to use the term Later or Late Modern Times or Age("Last Modern Times", "Late Modern Age" or "Post Modern Age"), contrasting it with the term Early Modern Times or Age ("Early Modern Times", "Early Modern Age" or "Previous Modern Age") since they still use the Celarius periodization; while they restrict the use of Contemporary Age to the 20th century, especially its second half.

The question of whether there was more continuity or more rupture between the Modern Age and the Contemporary depends, therefore, on the perspective. If modernity is defined as the development of a worldview with features derived from the values of anthropocentrism as opposed to those of medieval theocentrism (concepts of the world centered on man or God, respectively): the idea of social progress, individual freedom, knowledge through scientific research, etc.; then it is clear that the Contemporary Age is a continuation and intensification of all these concepts. Its origin was in Western Europe at the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th century, where Humanism, the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation emerged; and were accentuated during the so-called crisis of European conscience at the end of the 17th century, which included the Scientific Revolution and preluded the Enlightenment. The revolutions of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth can be understood as the culmination of trends started in the preceding period. Confidence in human beings and in scientific and technological progress was reflected from then on in a very characteristic philosophy: positivism; and in the various religious approaches that range from secularism to agnosticism, atheism or anticlericalism. Its ideological manifestations were very disparate, from nationalism to Marxism through social Darwinism and totalitarianism of the opposite sign; although the political and economic formulations of liberalism were the dominant ones, notably including the doctrine of human rights which, developed from earlier elements,Democracy in America, 1835-) to become the most universally accepted ideal of a form of government, with notable exceptions.

However, it was the evidence of the triumph of the forces of modernity that led precisely in the Contemporary Age to develop a parallel discourse of criticism of modernity, which in its most radical aspect led to nihilism. It is possible to follow the thread of this critique of modernity in romanticism and its search for the historical roots of peoples; in the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche and later movements (irrationalism, vitalism, existentialism, Frankfurt School); en los rasgos más experimentales del arte contemporáneo y la literatura contemporánea que, no obstante, reivindican para sí la condición de literatura o arte moderno (expresionismo, surrealismo, teatro del absurdo); en concepciones teóricas como la postmodernidad; y en la violenta resistencia que, tanto desde el movimiento obrero como desde posturas radicalmente conservadoras, se opuso a la gran transformación de economía y sociedad. Superar el ideal ilustrado de progreso y confianza optimista en las capacidades del ser humano, implicaba una noción progresista y de confianza en la capacidad del ser humano que efectúa esa crítica, por lo que esas «superaciones de la modernidad» fueron de hecho nuevas variantes del discurso moderno.

La «Era de la Revolución» (1776-1848)

En los años finales del siglo XVIII y los primeros del siglo XIX se derrumba el Antiguo Régimen de una forma que fue percibida por los contemporáneos como una aceleración del ritmo temporal de la historia, que trajo cambios trascendentales conseguidos tras vencer de forma violenta la oposición de las fuerzas interesadas en mantener el pasado: todos ellos requisitos para poder hablar de una revolución, y de lo que para Eric Hobsbawm es La Era de la Revolución. Suele hablarse de tres planos en el mismo proceso revolucionario: el económico, caracterizado por el triunfo del capitalismo industrial que supera la fase mercantilista y acaba con el predominio del sector primario (Revolución industrial); el social, caracterizado por el triunfo de la burguesía y su concepto de sociedad de clases basada en el mérito y la ética del trabajo, frente a la sociedad estamental dominada por los privilegiados desde el nacimiento (Revolución burguesa); y el político e ideológico, por el que se sustituyen las monarquías absolutas por sistemas representativos, con constituciones, parlamentos y división de poderes, justificados por la ideología liberal (Revolución liberal).

Revolución industrial

La Revolución industrial es la segunda de las transformaciones productivas verdaderamente decisivas que ha sufrido la humanidad, siendo la primera la Revolución Neolítica que transformó la humanidad paleolítica cazadora y recolectora en el mundo de aldeas agrícolas y tribus ganaderas que caracterizó desde entonces los siguientes milenios de prehistoria e historia.

La transformación de la sociedad preindustrial agropecuaria y rural en una sociedad industrial y urbana se inició propiamente con una nueva y decisiva transformación del mundo agrario, la llamada revolución agrícola que aumentó de forma importante los bajísimos rendimientos propios de la agricultura tradicional gracias a mejoras técnicas como la rotación de cultivos, la introducción de abonos y nuevos productos (especialmente la introducción en Europa de dos plantas americanas: el maíz y la papa). En todos los periodos anteriores, tanto en los imperios hidráulicos (Egipto, Mesopotamia, India o China antiguas), como en la Grecia y Roma esclavistas o la Europa feudal y del Antiguo Régimen, incluso en las sociedades más involucradas en las transformaciones del capitalismo comercial del moderno sistema mundial, era necesario que la gran mayoría de la fuerza de trabajo produjera alimentos, quedando una exigua minoría para la vida urbana y el escaso trabajo industrial, a un nivel tecnológico artesanal, con altos costes de producción. A partir de entonces, empieza a ser posible que los sustanciales excedentes agrícolas alimenten a una población creciente (inicio de la transición demográfica, por la disminución de la mortalidad y el mantenimiento de la natalidad en niveles altos) que está disponible para el trabajo industrial, primero en las propias casas de los campesinos (domestic system, putting-out system) y enseguida en grandes complejos fabriles (factory system) que permiten la división del trabajo que conduce al imparable proceso de especialización, tecnificación y mecanización. La mano de obra se proletariza al perder su sabiduría artesanal en beneficio de una máquina que realiza rápida e incansablemente el trabajo descompuesto en movimientos sencillos y repetitivos, en un proceso que llevará a la producción en serie y, más adelante (en el siglo XX, durante la Segunda revolución industrial), al fordismo, el taylorismo y la cadena de montaje. Si el producto es menos bello y deshumanizado (crítica de los partidarios del mundo preindustrial, como John Ruskin y William Morris), no es menos útil y sobre todo, es mucho más beneficioso para el empresario que lo consigue lanzar al mercado. Los costos de producción disminuyeron ostensiblemente, en parte porque al fabricarse de manera más rápida se invertía menos tiempo en su elaboración, y en parte porque las propias materias primas, al ser también explotadas por medios industriales, bajaron su coste. La estandarización de la producción reemplazó la exclusividad y escasez de los productos antiguos por la abundancia y el anonimato de los productos nuevos, todos iguales unos a otros.

La Revolución industrial iniciada en Inglaterra a mediados del siglo XVIII se extendió sucesivamente al resto del mundo mediante la difusión tecnológica (transferencia tecnológica), primero a Europa Noroccidental y después, en lo que se denominó Segunda revolución industrial (finales del siglo XIX), al resto de los posteriormente denominados países desarrollados (especialmente y con gran rapidez a Alemania, Estados Unidos y Japón; pero también, más lentamente, a Europa Meridional y a Europa Oriental). A finales del siglo XX, en el contexto de la denominada Tercera revolución industrial, los NIC o nuevos países industrializados (especialmente China) iniciaron un rápido crecimiento industrial. No obstante, la influencia de la revolución industrial, desde su mismo inicio se extendió al resto del mundo mucho antes de que se produjera la industrialización de cada uno de los países, dado el decisivo impacto que tuvo la posibilidad de adquirir grandes cantidades de productos industriales cada vez más baratos y diversificados. El mundo se dividió entre los que producían bienes manufacturados y los que tenían que conformarse con intercambiarlos por las materias primas, que no aportaban prácticamente valor añadido al lugar del que se extraían: las colonias y neocolonias (África, Asia y América Latina, tanto antes como después de los procesos de independencia de los siglos XIX y XX).

Motivos por los cuales la Revolución industrial surgió en Inglaterra

La Revolución industrial se originó en Inglaterra a causa de diversos factores, cuya elucidación es uno de los temas historiográficos más trascendentes.

Como factores técnicos, era uno de los países con mayor disponibilidad de las materias primas esenciales, sobre todo el carbón, mineral indispensable para alimentar la máquina de vapor que fue el gran motor de la Revolución industrial temprana, así como los altos hornos de la siderurgia, sector principal desde mediados del siglo XIX. Su ventaja frente a la madera, el combustible tradicional, no es tanto su poder calorífico como la mera posibilidad en la continuidad de suministro (la madera, a pesar de ser fuente renovable, está limitada por la deforestación; mientras que el carbón, combustible fósil y por tanto no renovable, solo lo está por el agotamiento de las reservas, cuya extensión se amplía con el precio y las posibilidades técnicas de extracción).

Como factores ideológicos, políticos y sociales, la sociedad inglesa había atravesado la llamada crisis del siglo XVII de una manera particular: mientras la Europa Meridional y Oriental se refeudalizaba y establecía monarquías absolutas, la guerra civil inglesa (1642-1651) y la posterior revolución gloriosa (1688) determinaron el establecimiento de una monarquía parlamentaria (definida ideológicamente por el liberalismo de John Locke) basada en la división de poderes, la libertad individual y un nivel de seguridad jurídica que proporcionaba suficientes garantías para el empresario privado; muchos de ellos surgidos de entre activas minorías de disidentes religiosos que en otras naciones no se hubieran consentido (la tesis de Max Weber vincula explícitamente La ética protestante y el espíritu del capitalismo). Síntoma importante fue el espectacular desarrollo del sistema de patentes industriales.

Como factor geoestratégico, durante el siglo XVIII Inglaterra (que tras las firmas del Acta de Unión con Escocia en 1707 y del Acta de Unión con Irlanda en 1800, después de la derrota de la rebelión irlandesa de 1798, consiguieron la unión con Escocia e Irlanda, formando el Reino Unido de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda) construyó una flota naval que la convirtió (desde el tratado de Utrecht, 1714, y de forma indiscutible desde la batalla de Trafalgar, 1805) en una verdadera talasocracia dueña de los mares y de un extensísimo imperio colonial. A pesar de la pérdida de las Trece Colonias, emancipadas en la Guerra de Independencia de Estados Unidos (1776-1781), controlaba, entre otros, los territorios del subcontinente indio, fuente importante de materias primas para su industria, destacadamente el algodón que alimentaba la industria textil, así como mercado cautivo para los productos de la metrópolis. La canción patriótica Rule Britannia (1740) explicitly stated: rule the waves.

The steam engine, coal, cotton and iron

The experimentation of the steam boiler was an ancient practice (the Greek Heron of Alexandria) that was resumed in the 16th century (the Spaniards Blasco de Garay and Jerónimo de Ayanz) and that at the end of the 17th century had produced encouraging results, although still technologically untapped (Denis Papin and Thomas Savery). In 1705 Thomas Newcomen had developed a steam engine efficient enough to pump water out of flooded mines. After successive improvements, in 1782 James Watt incorporated a feedback system that decisively increased its efficiency, which made it possible to apply it to other fields. First to the textile industry, which had previously developed a textile revolution applied to cotton threads and fabrics with the flying shuttle (John Kay, 1733) and the mechanical spinning machine (James Hargreaves' spinning Jenny -1764-, Richard Arkwright's hydraulic spinning machine -1769, moved by hydraulic power, applied at Cromford Mill from 1771- and Samuel Crompton's spinning mule, 1779); and that it was ripe for the application of steam to the mechanical loom (Edmund Cartwright's power loom, 1784) and other innovations demanded by the bottleneckswhich were forced into the successively affected subsectors, putting the English textile industry at the head of world cloth production. Then to transport: the steamboat (Robert Fulton, 1807) and later the railway (George Stephenson, 1829), whose development was hampered by the social misgivings it aroused; but that allowed extracting all the potential of the railways for mining use and animal and human traction that had been used extensively with Coalbrookdale iron melted with coke (Abraham Darby I, 1709; Iron Bridge, 1781). Steam, coal and iron were applied to all production processes susceptible to mechanization. Watt's invention had represented the decisive leap towards industrialization, and England, the first to do so, becamethe workshop of the world.

Opposition to changes

These novelties were not always well received. The replacement of human labor by machines condemned traditional crafts workers to unemployment if they did not adapt to the new working conditions or the loss of control of the production process if they did. Resistance against it led in some cases to the physical destruction of the new mechanized industries (Luddism). The new employers, freed from trade union restrictions, succeeded in outlawing any form of association for the defense of labor interests, leaving the negotiation of working conditions and salary solely to the individual contract and the free market. Symmetrically, the association of entrepreneurs was not allowed either, as it violated the principle of free competition,The Wealth of Nations, 1776). The historiographic debate on whether industrialization was a more or less detrimental process for the living conditions of the lower classes has been one of the most active, and it is not resolved. Jobs did not decrease, on the contrary, they increased, making necessary the arrival in the overcrowded working-class neighborhoods of the north of England (Manchester, Liverpool) of masses of emigrants from the countryside (from where they were expelled by the poor laws -laws of the poor- and the enclosures -enclosures-). On the contrary, the liberalization of the price of basic foodstuffs had to wait until the middle of the 19th century for the abolition of the Corn Laws.(Corn Laws, in force between 1815 and 1846) that defended the protectionist interests of British landowners, disproportionately represented in Parliament and fought by the pressure group of Manchester capitalism. The reduction in the salary level (which David Ricardo justified as an expression of an economic need, the bronze law), the long hours in unhealthy jobs and the generalized social degradation, led to pauperism (the harsh social conditions were portrayed in the novels of the time, such as Les Miserables by Victor Hugo, or Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens); while also creating the conditions for the emergence of a class consciousnessand the beginning of the labor movement. They also had political expression in the revolutions of 1830 and 1848, bourgeois in their social qualification, but with a strong working-class role, particularly in France; as well as British Chartism.

Demographic revolution

Other predictions, those of Thomas Malthus (Essay on the Principle of Population, 1798), warned pessimistically of the impossibility of maintaining the unusual population growth that England was experiencing, the first to undergo the transformations typical of the transition from the old to the new demographic regime. As they industrialized, other nations joined the same process, which involved decreasing mortality (two of the main causes of catastrophic mortality - famines and epidemics - had been substantially mitigated) while keeping birth rates high (there were neither effective contraceptive methods nor the social transformations that would make a decrease in the number of children desirable to families in the future).

One of the effects of all these changes, as well as an escape valve for social pressure, was the increase in emigration, the so-called white explosion.(Because it is the phase of the demographic revolution carried out by Europe and other areas with a predominantly European population). Ruined peasants and workers with nothing to lose, they were encouraged to leave Europe and try their luck in settlement colonies (Canada or Australia for the English, Algeria for the French) or in independent nations receiving immigrants (such as the United States or Argentina).); members of the upper classes were also incorporated as the ruling elite in exploitative colonies (such as India, Southeast Asia, or sub-Saharan Africa). Explicitly, the defenders of British imperialism, such as Cecil Rhodes, saw in immigration to the colonies the solution to social problems and a way to avoid class struggle. Marxist theorists interpreted it in a similar way,One of the largest national emigrations occurred after the Great Irish Famine of 1845–1849, which depopulated the island, both through mortality and through massive population transfer, which turned entire cities on the East Coast of the United States into ghettos. Irish (where they suffered discrimination from the dominant WASP, whose acronym stands for White Anglo-Saxon Protestants in Spanish). Other later waves were carried out by Nordic, German, Italian and Eastern European immigrants (especially the massive departures, at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, of the Jews subjected to the pogroms).

Liberal revolutions

Social, political and ideological context

Even before the transformations linked to the English industrial revolution affected other countries in a notable way, the growing economic power of the bourgeoisie collided in the societies of the Old Regime (almost all the other European ones, with the exception of the United Kingdom and the Netherlands).) with the privileges of the two privileged estates that retained their medieval prerogatives (clergy and nobility). The absolute monarchy, like its predecessor the authoritarian monarchy, had already begun to dispense with the aristocrats for the government, calling as ministers members of the lower nobility, lawyersand even people from the bourgeoisie, such as Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the finance minister of Louis XIV. The crisis of the Old Regime that took place during the 18th century made the bourgeoisie become aware of their own power, and they found ideological expression in the ideals of the Enlightenment, notably disclosed with L'Encyclopédie (1751-1772). With greater or lesser depth, several absolute monarchs adopted some ideas of enlightened reformism (Joseph II of Austria, Frederick II of Prussia, Charles III of Spain), the so-called enlightened despots to whom different variants of the expression all for the people are attributed, but without the people.The insufficiency of these lukewarm reforms was evidenced every time the most radical ones were mitigated, postponed or rejected, which affected structural aspects of the economic and social system (disentailment, disengagement, market freedom, abolition of jurisdictions, privileges, guilds, monopolies and internal customs, legal equality); while the untouchable political questions, which would imply questioning the very essence of absolutism, were rarely raised beyond theoretical exercises. The resistance of the structures of the Old Regime could only be overcome with popular-based revolutionary movements, which in the colonial territories were expressed in wars of independence.

Two closely related philosophical and legal notions played an important role in the ideology of these revolutions: the theory of human rights and constitutionalism. The idea that there are certain rights inherent to human beings is ancient (Cicero or scholasticism), but it was associated with the supramundane order. The enlightened (John Locke or Jean-Jacques Rousseau) defended the idea that these human rights are inherent to all human beings alike, by the mere fact of being rational beings, and therefore they are neither concessions from the State, nor do they derive from of any religious status (such as being "sons of God"). The secularization of politics did not necessarily imply the agnosticism or atheism of the enlightened, many of whom were sincere Christians, while others identified with pantheistic positions close to Freemasonry. The principle of religious tolerance was defended with vehemence and personal commitment by Voltaire, whose departure from the Catholic Church made him the most controversial figure of the time.

These rights are "natural rights", they are conceived as prior to the law of the State as opposed to the "positive rights" established by the different legal systems. The "rights of man" are collected in a Constitution ("constitutional rights") but not created by it. The constitutions or the declarations of rights explicitly declare that such rights belong to man with a universal character, and not by virtue of any fact of his own or others, or due to a particular condition (nationality, place or family of birth, religion, etc.).

Attributing to the State the inevitable tendency to overwhelm these rights (due to the corruption inherent in the exercise of power), the Enlightenment conceived of guaranteeing individual freedom by limiting it through a "Political Constitution", preferring the rule of law to the king's government. Although they could differ on their preferences regarding the definition of the political system, from the highest authority of the king to the principle of separation of powers (Montesquieu, The spirit of the laws, 1748) and, at its extreme, the principle of general will, national sovereignty and popular sovereignty (Jean Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract, 1762), understood that it should be governed by a Supreme Law that would meet the demands of reason and provide morepublic happiness (or rather would allow the pursuit of happinessindividual to each individual). Such a constitution, in its most radical interpretation, should be generated by the people and not by the monarchy or the ruler, since it is an expression of the sovereignty that resides in the nation and in the citizens (not in the monarch, as preached by the defenders of absolutism since the 17th century: Thomas Hobbes or Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet). To guarantee the balance of powers, the judiciary would have to be independent, and the legislative power would have to be exercised by a parliament that represents the nation and is elected by the people, or at least on their behalf, by an electoral body whose representativeness could be understood as more or less extensive or restricted. These formulations, based on the practice of British parliamentarism after the Glorious Revolutionof 1688, became the doctrinal body of political liberalism.

The influence that this example had on the political theorists of the Enlightenment, recognized in the writings of Voltaire or Montesquieu, was transcendental. Also the Constitution of the United States of America (1787), is strongly imbued in the British customary legal tradition. The choice for a written rather than a customary constitution is explained both by the influence of Enlightenment ideology on American constituents and by the fact that the British legal process had occurred over the span of some 600 years, while its American equivalent was produced in just a decade. The written text became indispensable to create a whole new political system from scratch, contrary to the British case, that had evolved with successive additions and decanted with over the centuries. It was reflected in the prestige of various legal texts (some medieval, such as theMagna Carta of 1215, other modern ones such as the Bill of Rights of 1689), the jurisprudence of courts with independent judges and juries and political uses, which implied a balance of powers between the Crown and Parliament (elected by unequal constituencies and restricted suffrage), to which His Majesty's Government responded. The first constitutions written in Europe were the Polish (May 3, 1791) and the French (September 3, 1791). However, the first modern legal document of its kind (rather a theoretical and utopian exercise that was not applied) was the Draft Constitution for Corsica that Jean Jacques Rousseau wrote for the short-lived Corsican Republic (1755-1769).The first Spanish ones appeared as a consequence of the Peninsular War: the one drawn up in Bayonne by the Frenchified (July 8, 1808) and the one drawn up by their rivals from the patriot side in the Cortes of Cádiz (March 12, 1812, popularly called Pepa)., taken as a model by others in Europe. In Latin America, the first constitutions were created between 1811 and 1812, as a consequence of the juntista movement, which was the first phase of the Hispano-American independence movement causing the colonial wars. The Congress of Angostura, with the inspiration of Simón Bolívar, drafted the Constitution of Cúcuta (or Gran Colombia).which included present-day Colombia, Ecuador, Panama and Venezuela) in 1819 and which the Congress of Cúcuta would end up officially proclaiming in 1821. All these movements would form part of what would be known as the Atlantic revolutions or the Atlantic cycle.

United States independence

The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants

The tree of liberty must be watered from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.Thomas Jefferson, 1787.

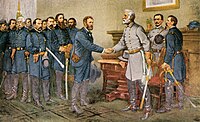

The English had settled in the Thirteen Colonies on the northwestern American coast since the 17th century. During the great colonial war between the United Kingdom and France (1756-1763), which was the American correlate of the European Seven Years' War, the American colonists became aware of the extent to which their interests diverged from those of the metropolis (impossibility to receive a balanced treatment, or to be promoted in the army), as well as the limits of its capacity and its own power. In the following years, faced with pressing fiscal needs, an attempt was made to increase the extraction of resources from the colonies by imposing taxes without any type of local control or representation in their discussion, such as the Sugar Law and the Seal Law. After the progressive cooling of relations, the settlers and theRedcoats (British troops named for the color of their uniform) had their first skirmishes in minor incidents whose importance was magnified into symbolic ones (Boston Massacre, 1770; Tea Party, 1773; Battles of Lexington and Concord, 1775). In 1776, at a Continental Congress meeting in the city of Philadelphia, representatives sent by the local parliaments of the Thirteen Colonies proclaimed independence. The war, led by George Washington on the colonial side, which received international support from France and Spain, ended with the complete defeat of the British at the Battle of Yorktown (1781). In the Treaty of Paris of 1783, the independence of the United States was recognized by the British Empire.

During the first years there were doubts among the founding fatherswhether the Thirteen Colonies would each go their own way like so many other independent nations, or whether they would form a single nation. In a new congress held again in Philadelphia (1787), they finally agreed on an intermediate solution, forming a federal state with a complex distribution of functions between the Federation and the member states, under the mandate of a single fundamental charter: the Constitution of 1787 The Federation, called the United States of America, was inspired for its creation and for the drafting of its Magna Carta (especially the numerous amendments that had to be added progressively to the seven initial articles) in the fundamental principles promoted by the Enlightenment, as well as in the political practice of local self-government experienced for more than a century,The political system was based on strong individualism and respect for human rights (although in its political culture they were expressed as civil rights), among which the greatest guarantees never existed in any legal system prior to the neutrality of the state. in matters pertaining to private life and respect for public liberties (conscience, expression, press, assembly and political participation, possession of weapons) and specifically private property as a vehicle for the pursuit of happiness (Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness).The construction of democracy, in many of its implications, such as universal suffrage, was not quickly achieved, especially regarding the problems of slavery, which differentiated the northern and southern states; and the relationship with the indigenous nations, through whose territories they expanded. The notions of republic and independence became two symbolic referents of the new nation, and for a long time, almost exclusive characteristics compared to the rest of the world.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Quentin de la Tour, 1753) is the intellectual father of the revolutions of the late eighteenth century. He sees fewer values in the corrupt society of the Old Regime than in the good savage (advanced in his Discours sur les Sciences et les Arts -«Discourse on the sciences and the arts»- and popularized with the novel Emilio). His doctrine of the Social Contract, based on this concept of the natural goodness of man, will lead to the search for national sovereignty, and later, for democracy, but it is also at the intellectual origin of the uniformizing and totalitarian state of the dictatorships of the 20th century. XX.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Quentin de la Tour, 1753) is the intellectual father of the revolutions of the late eighteenth century. He sees fewer values in the corrupt society of the Old Regime than in the good savage (advanced in his Discours sur les Sciences et les Arts -«Discourse on the sciences and the arts»- and popularized with the novel Emilio). His doctrine of the Social Contract, based on this concept of the natural goodness of man, will lead to the search for national sovereignty, and later, for democracy, but it is also at the intellectual origin of the uniformizing and totalitarian state of the dictatorships of the 20th century. XX. John Trumbull's Declaration of Independence, 1817. Submission to the Continental Congress by the "Five Men" Commission of the proposed United States Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776). They appear among others Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and James Wilson. In this text, the values of the Enlightenment were applied to the construction of the first contemporary political system. The reception of this experience in Europe, mainly in France, was a mixture of sympathy and paternalism: the myth of the noble savagecontributed to this, and also the diplomatic skill of Franklin himself, ambassador to Paris. The Americans presented themselves as resistant to tyranny, with neoclassical references to the ancient Roman Republic, of which they will see heirs from then on (New Rome)

John Trumbull's Declaration of Independence, 1817. Submission to the Continental Congress by the "Five Men" Commission of the proposed United States Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776). They appear among others Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and James Wilson. In this text, the values of the Enlightenment were applied to the construction of the first contemporary political system. The reception of this experience in Europe, mainly in France, was a mixture of sympathy and paternalism: the myth of the noble savagecontributed to this, and also the diplomatic skill of Franklin himself, ambassador to Paris. The Americans presented themselves as resistant to tyranny, with neoclassical references to the ancient Roman Republic, of which they will see heirs from then on (New Rome) General and first President George Washington fires French nobleman and fellow General Gilbert de La Fayette (1784). At the head of troops from the French monarchy, he had supported the independence of the Thirteen Colonies from England, as did the Spanish governor of Louisiana Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid and the French soldier Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur de Rochambeau, in an adjustment of accounts from the previous Seven Years' War. La Fayette, influenced by his American experience, advocated moderate reforms and a constitutional monarchy during the subsequent revolutionary events in France.

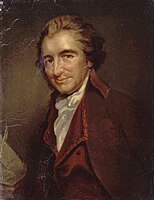

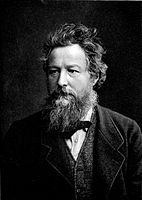

General and first President George Washington fires French nobleman and fellow General Gilbert de La Fayette (1784). At the head of troops from the French monarchy, he had supported the independence of the Thirteen Colonies from England, as did the Spanish governor of Louisiana Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid and the French soldier Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur de Rochambeau, in an adjustment of accounts from the previous Seven Years' War. La Fayette, influenced by his American experience, advocated moderate reforms and a constitutional monarchy during the subsequent revolutionary events in France. The British Thomas Paine had a vital trajectory linked to the American and French revolutions. Expelled from England, he too had problems with the period of Robespierre's Terror, and ended his life on American soil. He was the author of three important books: the liberal Common Sense in which he defends independence from the United States, the controversial The Rights of Man in response to the attack on France's revolutionary excesses by Edmund Burke (who, on the contrary, had defended the Americana, although with more conservative arguments than Paine's radicals); and the anticlerical and Voltairean The Age of Reason (The age of reason).

The British Thomas Paine had a vital trajectory linked to the American and French revolutions. Expelled from England, he too had problems with the period of Robespierre's Terror, and ended his life on American soil. He was the author of three important books: the liberal Common Sense in which he defends independence from the United States, the controversial The Rights of Man in response to the attack on France's revolutionary excesses by Edmund Burke (who, on the contrary, had defended the Americana, although with more conservative arguments than Paine's radicals); and the anticlerical and Voltairean The Age of Reason (The age of reason).

Revolución francesa e Imperio napoleónico

Qu'est-ce que le tiers état? Tout. Qu'a-t-il été jusqu'à présent dans l’ordre politique? Rien. Que demande-t-il? À y devenir quelque chose.

¿Qué es el tercer estado? Todo. ¿Qué ha sido hasta el presente en el orden político? Nada. ¿Qué demanda? Llegar a ser algo.

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, ¿Qué es el tercer estado?, 1789.

Francia había apoyado activamente a las Trece Colonias contra el Reino Unido, con tropas comandadas por el Marqués de La Fayette; pero aunque la intervención fue exitosa militarmente, le costó cara a la monarquía francesa, y no solo en términos monetarios. Sumada a la deuda cuyos intereses ya se llevaban la mayor parte del presupuesto, y en medio de una crisis económica, llevó a la monarquía al borde de la quiebra financiera. Las deposiciones sucesivas de Charles Alexandre de Calonne, Anne Robert Jacques Turgot y Jacques Necker, los ministros que proponían reformas más profundas, hicieron al gobierno de Luis XVI y María Antonieta aún más impopular. El rey, sin apoyo entre la aristocracia que controlaba las instituciones (negativa de la Asamblea de notables de 1787), aceptó como mejor salida convocar a los Estados Generales, parlamento de origen medieval en el que estaban representados los tres estamentos, y que no se reunía desde hacía más de cien años. Durante la elección de los diputados, se habían de redactar cuadernos de quejas, peticiones que representaban el pulso de la opinión de cada parte del país. Siguiendo el argumentario ilustrado, las del Tercer Estado (el pueblo llano o los no privilegiados, cuyo portavoz era la burguesía urbana) pedían que los estamentos privilegiados (clero y nobleza) pagaran impuestos como el resto de los súbditos de la corona francesa, entre otras profundas transformaciones sociales, económicas y políticas. Una vez reunidos, no hubo acuerdo sobre el sistema de votación (el tradicional, por brazos, daba un voto a cada uno, mientras que el individual favorecía al Tercer Estado, que había obtenido previamente la convocatoria de un número mayor de estos). Finalmente, los diputados del Tercer Estado, a los que se sumaron un buen número de nobles y eclesiásticos próximos ideológicamente a ellos, se reunió por separado para formar una autodenominada Asamblea Nacional.

El 14 de julio de 1789 el pueblo de París, en un movimiento espontáneo, tomó la fortaleza de La Bastilla, símbolo de la autoridad real. El rey, sorprendido por los acontecimientos, hizo concesiones a los revolucionarios, que tras la Declaración de Derechos del Hombre y del Ciudadano y la eliminación de las cargas feudales, en lo relativo a la forma de gobierno solo aspiraban a establecer una monarquía limitada como la británica, pero con una Constitución escrita. La Constitución de 1791 confería el poder a una Asamblea Legislativa que quedó en manos de los más radicales (los miembros de la Constituyente aceptaron no poder ser reelegidos) y profundizó las transformaciones revolucionarias. Tras el intento de fuga del rey, este quedó prisionero, y en 1792 la Francia revolucionaria tubo de rechazar la invasión de una coalición de potencias europeas, decididas a aplastar el movimiento revolucionario antes de que el ejemplo se contagiase a sus territorios. La eficacia del ejército revolucionario, motivado por el patriotismo (La Marsellesa, La patrie en danger -La patria en peligro-, Levée en masse -Leva en masa-) y la defensa de lo conquistado por el pueblo, frente a los desmotivados ejércitos mercenarios, cuyos oficiales no lo eran por mérito, sino por nobleza, demostró ser suficiente para la victoria. En el interior, la revuelta del 10 de agosto de 1792, protagonizada por los sans culottes (la plebe urbana de París) forzó a la Asamblea a sustituir al rey por un Consejo provisional y convocar elecciones por sufragio universal a una Convención Nacional, que dominaron los jacobinos. Su política de supresión de toda oposición, el llamado Terror (1793-1795), eliminó físicamente a la oposición contrarrevolucionaria (muy fuerte en algunas zonas, representada en las Guerras de Vendée y de los Chaunes) así como a los elementos revolucionarios más moderados (girondinos), mientras los que pudieron huir (nobles y clérigos refractarios, que no habían aceptado jurar la constitución civil del clero) salían al exilio. Se estableció un régimen político republicano, que transformó incluso el calendario, establecía un sistema de precios y salarios máximos (ley del máximum general) y controlaba todos los aspectos de la vida pública mediante el Comité de Salud Pública dirigido por Maximilien Robespierre. El número de ejecuciones, por el igualitario método de la guillotina fue muy alto, e incluyó al rey y a la reina, a los girondinos (como Jacques Pierre Brissot y Nicolas de Condorcet), así como a varios de los propios jacobinos, como Georges-Jacques Danton, y a un gran científico, Antoine Lavoisier (en ocasión de su condena, se dijo: la revolución no necesita sabios). Un golpe de estado (conocido como reacción thermidoriana, por el nombre en el nuevo calendario del mes en que se produjo) acabó físicamente con Robespierre y su régimen e instauró un sistema mucho más moderado: el Directorio (1795-1799).

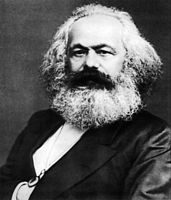

Modelo de proceso revolucionario

La Revolución francesa asentó así un modelo de proceso revolucionario dividido en fases: iniciada con una revuelta de los privilegiados, pasa por una fase moderada y una fase radical o exaltada para acabar con una reacción que propicia la plasmación de un poder personal. Las expresiones, comunes en la historiografía, destacan por su similitud con las fases en que se dividió la Revolución rusa. Georges Lefebvre señala tres fases en la primera parte de la revolución: aristocrática, burguesa y popular. Para Karl Marx (en su estudio comparativo que tituló El 18 Brumario de Luis Bonaparte), el proceso de la revolución de 1789 fue ascendente, mientras que el de la de 1848 fue descendente.

Para Hannah Arendt, mientras que la Independencia de los Estados Unidos sería un modelo de revolución política, y de ahí su continuidad, la Revolución francesa sería un modelo de revolución social, y de ahí su fracaso, como el de las revoluciones que siguen su modelo (especialmente la rusa); pues (como planteaba ya Alexis de Tocqueville) los logros políticos de la libertad y la democracia solamente se consolidan cuando son el resultado de procesos sociales y económicos anteriores, y no cuando se plantean como requisitos previos para conseguir estos.

La analogía entre los periodos de la historia de Roma (Monarquía-República-Imperio) y los mucho más efímeros de la Revolución de 1789 (repetidos en la evolución posterior de la historia de Estados Unidos) no dejó de ser tenida en cuenta por los propios contemporáneos, que no solo se inspiraban en la antigüedad grecorromana para el arte neoclásico, sino también para su sistema político y sus símbolos (gorro frigio, fasces, águila romana, etc.).

Napoleón Bonaparte

En ese contexto se inició la carrera de Napoleón Bonaparte, un militar proveniente de una familia de provincias que nunca hubiera conseguido ascender en el ejército de la monarquía, y que se convirtió en un héroe popular por sus campañas en Italia y en Egipto y Siria. En 1799 se sumó al golpe de estado del 18 de brumario (nombrado por la fecha en que se llevó a cabo el golpe según el calendario republicano francés) que derribó al Directorio e instauró el Consulado, del que fue nombrado primer cónsul para, en 1804, proclamarse Emperador de los franceses (no de Francia, en una sutil diferenciación con el régimen monárquico que pretendía mantener los ideales republicanos y de la revolución). En sus años en el poder (hasta 1814, y luego el breve periodo de los cien días de 1815), Napoleón consiguió dejar un extenso legado. Consciente de que no podía retomar el Derecho del Antiguo Régimen, pero sumergido en el marasmo de la atropellada y caótica legislación revolucionaria, dio la orden de compendiar todo ese legado jurídico en cuerpos legales manejables. Nació así el Código Civil de Francia o Código Napoleónico, inspiración para todos los demás estados liberales, y que contribuyó a propagar la Revolución en cuanto superestructura jurídica que expresaba la sociedad burguesa-capitalista. Le siguieron después un Código de Comercio, un Código Penal y un Código de Instrucción Criminal, este último antecedente del derecho procesal moderno. Emprendió una serie de reformas administrativas y tributarias, que eliminaron privilegios y fueros territoriales a favor de una nación unitaria y centralizada, que concebía como un Estado de Derecho (en sus propias palabras: el hombre más poderoso de Francia es el juez de instrucción). Para sustituir a la antigua nobleza creó la Legión de Honor, la más alta distinción del Estado, que reconocía no el privilegio de cuna o la riqueza, sino el mérito personal. Su círculo de confianza, compuesto por parientes como sus hermanos José o Jerónimo, y generales como Joaquín Murat o Carlos XIV Juan de Berbadotte, terminaron ocupando tronos europeos. Frente a la descristianización emprendida en El Terror, aprovechó la sumisión del papado para la firma de un Concordato que ponía el clero bajo control estatal, pero garantizaba la continuidad del catolicismo como religión de Francia, pretendiendo simbolizar con ello la reconciliación de los franceses. El régimen político, jurídico e institucional napoleónico, reconducción en un sentido autoritario de los ideales revolucionarios de 1789, se transformó en modelo para muchos otros por todo el mundo.

Declaración de los Derechos del Hombre y del Ciudadano, 26 de agosto de 1789. Con una voluntad universalista e ilustrada, supuso una invitación a la extensión de las ideas revolucionarias a las demás naciones.

Declaración de los Derechos del Hombre y del Ciudadano, 26 de agosto de 1789. Con una voluntad universalista e ilustrada, supuso una invitación a la extensión de las ideas revolucionarias a las demás naciones. Ejecución de Luis XVI, 21 de enero de 1793. La ejecución por su pueblo de un rey que según todo el ideario político de su tiempo, tenía poderes absolutos, causó un impacto enorme, ya con todas las monarquías europeas solidarizaron en guerra contra la Revolución.

Ejecución de Luis XVI, 21 de enero de 1793. La ejecución por su pueblo de un rey que según todo el ideario político de su tiempo, tenía poderes absolutos, causó un impacto enorme, ya con todas las monarquías europeas solidarizaron en guerra contra la Revolución. Napoleón cruzando los Alpes de Jacques-Louis David, 1801. Hijo de la Revolución, de ideario igualitarista (se dice que ponía en la mochila de cada soldado el bastón de mariscal), plasmó los ideales revolucionarios en una nueva institucionalidad política, administrativa y jurídica.

Napoleón cruzando los Alpes de Jacques-Louis David, 1801. Hijo de la Revolución, de ideario igualitarista (se dice que ponía en la mochila de cada soldado el bastón de mariscal), plasmó los ideales revolucionarios en una nueva institucionalidad política, administrativa y jurídica. El tres de mayo de 1808 en Madrid, por Francisco de Goya, 1814. La lucha entre las fuerzas napoleónicas y los defensores del Antiguo Régimen obligó a los pueblos europeos a tomar partido no solo militar, sino también ideológico, e ingresar así a la Edad Contemporánea.

El tres de mayo de 1808 en Madrid, por Francisco de Goya, 1814. La lucha entre las fuerzas napoleónicas y los defensores del Antiguo Régimen obligó a los pueblos europeos a tomar partido no solo militar, sino también ideológico, e ingresar así a la Edad Contemporánea.

Movimiento independentista en América Latina

Rebelión de esclavos en Haití

Con una represión cada vez mayor hacia los mulatos y negros en la colonia francesa de Saint-Domingue, empezó a darse las primeras insurrecciones entre 1748 y 1790. El 14 de agosto de 1791, se celebró la ceremonia de Bois Caïman, organizada por el sacerdote vudú Dutty Boukman, que termina con la orden de levantarse de forma organizada. Esto provocó que pocos días después comenzaran una sangrienta masacre en el norte de la isla. A la muerte de Boukman en noviembre del mismo año, se da la abolición de la esclavitud en 1792 por Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, en parte debido a la búsqueda de aliados para combatir contra las tropas españolas y británicas.

Con la llegada del general Toussaint Louverture al mando de un puñado de soldados, logró retener a las tropas británicas e invadir la parte española de la isla, consiguiendo el poder de la colonia. Esto llevó a que Napoleón enviara a 20.000 efectivos encabezados por Charles Leclerc a restablecer su dominio en la isla (1801). Toussaint respondió a la reconquista francesa con la quema de tierra y empezando una guerra de guerrillas. En 1802, el revolucionario le ofrece su capitulación con la condición de quedar libre y de que sus tropas se integraran en el Ejército francés. Leclerc logra capturar a Toussaint y lo envía a Francia para ser aprisionado. Pese a que este fue capturado, Jean-Jacques Dessalines dirigió la rebelión, iniciando una ofensiva que termina con la decisiva batalla de Vertières (1803), cuya victoria termina con la proclamación de la independencia del país (1804), proclamándose como el Imperio de Haití y declarando a Dessalines como Jacques I of Haiti.

Brazil: from colony to independent empire

After the exile of the Portuguese Court due to the invasion of the French troops led by Napoleon I (1807), settling in Rio de Janeiro, Juan VI, in replacement of his incapacitated mother Maria I, decided to raise Brazil from a colony to a kingdom (1808), forming the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarve (1815).

In 1820, when the Liberal Revolution broke out in Portugal, the Portuguese Cortes forced the Portuguese royal family to return to Lisbon. However, before leaving, King John VI appointed his eldest son, Pedro de Alcántara Bragança, known as Pedro IV, as Prince Regent of Brazil (1821). The Portuguese Courts tried to transform Brazil into a colony once again, depriving it of the rights it had had since 1808, provoking the rejection of the Brazilians. The main leader of the Portuguese official, General Jorge Avilés, forced the prince to resign but he refused because of his position in favor of the Brazilian cause. After Pedro's decision to defy the Cortes, close to two thousand men led by Jorge Avilés himself mutinied before focusing on Monte Castelo, which was soon surrounded by 10,000 armed Brazilians, led by the Royal Police Guard. The radical liberals remained active: at the initiative of Joaquim Gonçalves Ledo, a representation was addressed to Pedro to expose the advisability of convening a Constituent Assembly. The prince decreed his summons on June 13, 1822. Popular pressure would carry the summons forward. José Bonifácio resisted the idea of convening the Constituent Assembly, but was forced to accept it. He tried to discredit it, proposing direct elections, which ended up prevailing against the will of the radical liberals, who defended indirect elections. After this, José Bonifácio was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom. Bonifácio established a friendly relationship with Pedro,

Pedro left for São Paulo to ensure the loyalty of the province to the Brazilian cause. He arrived in his capital on August 25 and stayed there until September 5. When he returned to Rio de Janeiro on September 7, he received two letters, one from José Bonifácio, who advised Dom Pedro to break with the metropolis, and another from his wife, María Leopoldina, who supported the proclamation of independence.. The prince learned that the Cortes had annulled all the acts of the cabinet and withdrawn the remaining power that he still had. Pedro turned to his companions and with the phrase "Independence or death!" (event known as the Cry of Ipiranga), broke political ties with Portugal. On October 12, 1822, in Campo de Santana, Prince Pedro was proclaimed as Pedro I, constitutional emperor and Perpetual Defender of Brazil.

Once the process was consolidated in the southeastern region of Brazil, the independence of the other regions of Portuguese America was achieved relatively quickly. He contributed to this diplomatic and financial support from Great Britain. Without an army and without a Navy, it became necessary to recruit foreign mercenaries and officers. Thus the Portuguese fortress in the provinces of Bahia, Maranhão, Piauí and Pará was drowned. The military process was completed in 1823, leaving behind the diplomatic negotiation of the recognition of the independence of the European monarchies. Brazil negotiated with Britain and agreed to pay £2 million in damages to Portugal in an agreement known as the Treaty of Rio de Janeiro. And so Brazilian independence was definitively maintained.

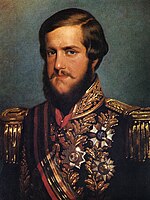

Pedro I, first emperor of the Empire of Brazil.

Pedro I, first emperor of the Empire of Brazil. José Bonifácio, one of the most important figures during the Brazilian independence process.

José Bonifácio, one of the most important figures during the Brazilian independence process.

Hispanic American Independence

The part of America subjected to Spanish colonial rule since the 16th century and that between the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th had gone through a critical situation of external lack of control (the activity of corsairs, generalized smuggling and the intervention of other European powers, notably England) while a certain local self-government was established in internal matters; by the middle of the 18th century it had already stabilized. The social structure was that of a pyramid of castes in which, above the vast majority of indigenous, mestizo, mulatto and black people (whose opinion did not count, and did not count in the process of independence), a prosperous class of Spanish landowners and merchants born in Latin America (the criollos), who increasingly endured the numerous administrative, legal,peninsularappointed in the distant Court. The Creoles sought not so much to emancipate themselves as to change power relations for their benefit; only an ideologized minority of exalted, a large part grouped in Masonic lodges such as the Lautarina Lodge, had independence as one of their purposes. The enlightened reforms that since Carlos III were relaxing the trade monopoly of Cadiz for the benefit of other peninsular ports or neutral countries (Decrees of freedom of trade with the American colonies, 1765, 1778 and 1797), were not considered sufficiently attractive. Other more radical proposals, which sought a restructuring of the viceroyalty system giving the American viceroyalties a certain degree of autonomy, were not taken into account by the power structures of the monarchy.

La independencia no se inició a partir de rebeliones indigenistas, como la promovida por Túpac Amaru II en Perú (1780-1782); sino que el desencadenante del proceso fue el cautiverio de Fernando VII al inicio de la Guerra de Independencia Española (1808). Napoleón Bonaparte envió emisarios a Hispanoamérica para exigir el reconocimiento de su hermano José I Bonaparte como rey de España después de las Abdicaciones de Bayona. Las autoridades locales se negaron a someterse, por razones tanto externas como internas. Externamente era evidente la debilidad de la posición francesa en ese continente (fracasos de Napoleón en retener la Luisiana, vendida a Estados Unidos en 1803, y Haití, independizado en 1804) frente a la más efectiva presencia británica (invasiones inglesas en el Río de la Plata, 1806-1807) que gracias a su predominio naval y económico, y a la habilidad con que dosificó su apoyo político a las nuevas repúblicas, terminó convirtiéndose en la potencia neocolonial de toda la zona, y de hecho el principal beneficiario de la disgregación del Imperio español. Internamente existía la presión de una movilización popular muy similar a la que simultáneamente estaba produciéndose en la Península, a la que se añadía en este caso el sentimiento independentista (primero minoritario pero cada vez más extendido entre los criollos). El movimiento juntista, en nombre del rey cautivo o invocando el poder nacional soberano (en consonancia con la ideología liberal) organizó Juntas de Gobierno convocadas en cada capital de gobernación o virreinato, aprovechando la ocasión para introducir reformas económicas, incluyendo la libertad de comercio o la libertad de vientres. Las Juntas hispanoamericanas no tuvieron una integración, como sí las peninsulares, en las nuevas instituciones que se formaron en Cádiz (Regencia y Cortes de Cádiz), y las autoridades enviadas por estas para restablecer la normalidad institucional en América no fueron recibidas con normalidad. Los elementos más fidelistas o realistas se enfrentaron a los juntistas, mediante maniobras políticas (arresto del virrey José de Iturrigaray en México) o incluso abiertamente y por mano militar (enfrentamiento entre Francisco de Miranda y Domingo de Monteverde en Venezuela o José Gervasio Artigas y Francisco Javier de Elío en la Banda Oriental), sobre todo tras la victoria del bando patriota en la Guerra de Independencia Española, que trajo como consecuencia la reposición en el trono de Fernando VII (1814). En consonancia con la política de restauración absolutista emprendida en la Península, se inició una movilización militar para abatir el movimiento insurgente de las colonias, cada vez más emancipadas de hecho. Los patriotas hispanoamericanos quedaron definitivamente abocados a luchar inequívocamente por la independencia, al ser evidente que tanto la libertad política como la económica estaba vinculada a ella y no podría conseguirse como concesión del gobierno absolutista de Fernando VII. Se formaron ejércitos, y en campañas militares de varios años, los caudillos libertadores consiguieron acabar con la presencia española en el continente, muy debilitada y no eficazmente renovada (el cuerpo expedicionario reunido en Cádiz en 1820 no embarcó a su destino, sino que se utilizó por el militar liberal Rafael de Riego para forzar al rey a someterse a la Constitución durante el llamado trienio liberal). La independencia hispanoamericana fue así, a la vez, tanto una de las principales consecuencias como una de las principales causas de la crisis final del Antiguo Régimen en España.

La Revolución de Mayo (1810) derrocó al último virrey en las actuales Argentina y Uruguay (que se unió a la revolución con el Grito de Asencio, 1811), y en plena guerra, se declara independiente (1816). Más tarde y a pesar de no tener el apoyo del gobierno de Buenos Aires, José de San Martín invadió Chile a través de los Andes (1817), y desde allí, con el apoyo del gobierno de Bernardo O'Higgins y del militar británico Thomas Cochrane, se embarcó rumbo a Perú (1820), conectándose con las fuerzas dirigidas por Simón Bolívar. Bolívar había desarrollado previamente exitosas campañas (batallas de Carabobo, 1814 y Boyacá, 1819) por la zona que pasó a denominarse Gran Colombia (conformadas por las actuales Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador y Panamá); aunque no logró el triunfo decisivo hasta que uno de sus lugartenientes, el Mariscal José de Sucre derrotó al último bastión realista enclavado en la zona de Perú y Bolivia (denominada así en su honor) en las batallas de Pichincha (1822) y Ayacucho (1824). Paralelamente, en México se desarrolló un movimiento revolucionario propio, que con el debatido Grito de Dolores (1810), desencadenó levantamientos armados dirigidos por José María Morelos y Vicente Guerrero que llevó a la proclamación de la independencia por Agustín de Iturbide, nombrado Emperador (1821), título derivado de la posibilidad, ofrecida a Fernando VII y rechazada por este, de restablecer la monarquía española en América del Norte de una manera pactada, con un título imperial y sin competencias efectivas. También San Martín había propuesto una solución semejante (cuyo título hubiera derivado en un descendiente inca con la propuesta rioplatense del Plan del Inca), a la que renunció ante la radical oposición de Bolívar, firme partidario del republicanismo y de la total desvinculación de cualquier lazo con España (Entrevista de Guayaquil, 26 de julio de 1822).

A pesar de los ideales panamericanos de Simón Bolívar, que aspiraba a reunir a todas las repúblicas a semejanza de las Trece Colonias, estas no solo no se reunieron, sino que siguieron disgregándose. La Gran Colombia se disolvió en 1830 por la separación de Venezuela y Ecuador, quedando formado la República de la Nueva Granada. Por su parte Uruguay, provincia oriental de las Provincias Unidas del Río de la Plata y provincia Cisplatina durante la ocupación luso-brasileña, se independizó de su núcleo central, Argentina y del Imperio del Brasil en 1828 (Convención Preliminar de Paz), quedando consolidado en 1830. La independencia de Bolivia lo desvinculó tanto de Argentina, que previamente había aceptado la no incorporación de Potosí, que estaba prevista, y de Perú al declararse la República de Bolívar (1825). Años después, en un intento por crear una Confederación Perú-Boliviana (1836-1839), terminó con su derrota militar a manos de las tropas chilenas y de los restauradores peruanos, provocando la disolución de la confederación. Las Provincias Unidas del Centro de América (independizadas pacíficamente de España en 1821, anexadas a México en 1822) se independizaron del Primer Imperio mexicano al transformarse este en república (1823) para formar la República Federal de Centroamérica, que a su vez se disolvió en las actuales Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala y Nicaragua entre 1838 y 1840, años después de la guerra civil de 1826-1829. El Haití Español (actual República Dominicana), independizado en 1821 y que pretendía quedar incorporada a la Gran Colombia, terminó anexada por fuerzas haitianas en 1822, independizándose de Haití en 1844. Paraguay, que había iniciado su andadura independiente en 1811 sin oposición efectiva tras fracasar el intento rioplatense de incorporarlo (Tratado confederal entre las juntas de Asunción y Buenos Aires, 1811), permaneció ajeno a esas unificaciones y divisiones, al igual que Chile.

Hispanic-American republicanism did not build democratic political options, and equality was seen (in terms similar to those of Tocqueville) as a threat to the social balance of a citizenry in precarious construction. Internal struggles between federalists and centralists characterized the first decades of the 19th century, followed by those that divided liberals and conservatives.

The priest Hidalgo, precursor of the independence of Mexico.

The priest Hidalgo, precursor of the independence of Mexico. Simón Bolívar, the most decisive of the liberators in Latin America.

Simón Bolívar, the most decisive of the liberators in Latin America. José de San Martín, from Argentina, played a role of similar importance.

José de San Martín, from Argentina, played a role of similar importance.

Other revolutionary movements and cycles

The so-called Age of Revolutions extended the American and French example. In some cases, simultaneously with these and with greater or lesser success, as occurred in some autonomous cities of Europe (Liège in 1791, for example). In the first half of the 19th century, a series of revolutionary cycles have been determined, named by the year they began (1820, 1830 and 1848).

Revolution of 1820

The Revolution of 1820 or the Mediterranean cycle began in Spain (Rafael de Riego's uprising or pronouncement against the expeditionary force that was going to embark for America, January 1, 1820) and spread, on the one hand, to Portugal, which in the called Liberal Wars-Oporto Revolution-, on August 24, 1820, the Portuguese government was forced to return from Brazil in a civil war in which, unlike in the case of Latin American independence, it was in the metropolis where the most liberal elements controlled the situation to the detriment of the most traditionalist branch of the dynasty; and on the other to Italy where secret societies, such as the Carbonari, initiate nationalist uprisings against the Austrian monarchies in the north and the Bourbon monarchies in the south, proposing the Spanish Constitution of Cadiz as an applicable text for themselves. In a less linked way, the uprising of the Greeks that began in 1821, who emancipated themselves from the Ottoman Empire in 1829 with the decisive support of the European powers (mainly France, England and Russia), is also located chronologically close. proclaiming the Greek State. Significantly, it was the same powers (with the exception of England and the addition of Austria and Prussia) who actively staged the counter-revolution to jointly put down, through theHoly Alliance revolutionary outbreaks that could threaten the continuity of absolute monarchies, and continued to do so until 1848.

Revolution of 1830

The revolution of 1830, which began with the three glorious days in Paris in which the barricades brought Louis Philippe d'Orléans to the throne, spread across the European continent with the independence of Belgium and less successful movements in Germany, Italy and Poland. In England, on the other hand, the beginning of the Chartist movement opted for the reformist strategy, which with successive expansions of the electoral base managed to slowly increase the representativeness of the political system, although universal male suffrage was not achieved until the 20th century. Doctrinalism was the ideology that expressed that moderation of liberalism.

Revolution of 1848. The "spring of the peoples" and nationalism

The era of the revolution will close with the revolution of 1848 or spring of the peoples. It was the most widespread throughout the continent (also started in Paris and spread through Italy and all of Central Europe with amazing speed, only explainable by the revolution in transport and communications), and initially the most successful (within a few months the most of the affected governments). But, in reality, these revolutionary movements did not lead to the formation of regimes of a radical or democratic nature that would achieve sufficient continuity, and in all cases the political situation quickly returned to moderation. In the case of France, an insurrection managed to overthrow the reigning monarchy, giving way to the Second Republic, which would last until the coup d'état of 1851, from which the Second Empire would be established with Napoleon III (1852-1870); while in Italy, after the outbreak of the First War of Italian Independence, it gave way to the beginning of the unification of the country, which would not culminate until 1870; On the other hand, in Germany the revolution lasted until 1849, and despite its partial failure, it was the direct precedent of the eventual dissolution of the Germanic Confederation (1866), which opened the debate on how to carry out the process of German unification (question German).

From this key moment, located in the mid-nineteenth century and that Eric Hobsbawm calls the era of capital, the historical forces change trend: the bourgeoisie goes from revolutionary to conservative and the labor movement begins to organize itself; although without a doubt the most capable of mobilizing the populations will be the nationalist movements.

Revolutions outside Europe

Outside the Western world, although one cannot speak of revolutionary movements unleashed by similar socioeconomic causes (bourgeois revolution), the term revolutions is sometimes used to designate one or another of the different Westernizing or modernizing movements that were implanted with greater or lesser less successful in one country or another, and that were more or less distantly inspired by the idea of progress, the Enlightenment, or some more or less explicit reference to one of the ideals of 1789. Generally, in the absence of a social base, they were promoted from power or circles close to it, and they explicitly condemned whatever disorder or destabilization the revolutionary term could have: Meiji era in Japan (1868), the failed Sepoy Rebellion in India (1857), the so-called Young Ottomans and Young Turks in the Ottoman Empire (1871 and 1908), rebellions such as the Taiping (1850) and the Boxer (1900-1901) demonstrated the social discontent that later triggered the Wuchang uprising in 1911 that abolished the Chinese Empire (Xinhai Revolution), various reform initiatives of the Russian Empire (such as the abolition of serfdom in 1861) etc.; and that they arrived chronologically until the First World War.

Reaction against the Enlightenment: Romanticism

Romanticism is the overcoming of reason as a method of knowledge, for the benefit of intuition and shared feeling (endopathy). Instead of the individual subject of universal rights, he conceives of singular persons, linked in natural communities: the peoples (a cultural concept typical of German romanticism - volk, people, and volkgeist, spirit of the people-) and nations (as understood by the French liberals, the political community based on the will). If the Enlightenment understood that the meeting of men originates society, romanticism inverts the terms, denying the existence of a man in a state of nature. Romantic are both reactionary traditionalism and revolutionary nationalism. The first (Louis de Bonald, Joseph de Maistre) conceive the town as a historical reality, anchored in the past and whose living members cannot decide their destiny or claim rightsthat they do not have, such as making decisions against their institutions, customs and values. The latter (Giuseppe Mazzini) dare to change the world and remove secular borders as long as they include individuals from a single people, which must be sovereign, independent of any authority that does not emanate from itself, and free to decide its destiny.

Pre-romanticism had emerged in the second half of the 18th century (Goethe 's The Misadventures of Young Werther, or Horace Walpole's Gothic novel), coinciding with the predominance of neoclassicism, so that although one is a reaction against the other, there are those who affirm that they are two phases of the same intellectual movement. The revolution was identified with the heroic virtues of classical antiquity expressed pictorially in the neoclassicism of Jacques-Louis David (Oath of the Horatii, portraits of Napoleon).

The literature of Romanticism was filled with literary types tormented by passions, in constant struggle against a society that refuses to give freedom to the individual. The English Lord Byron, Percy Shelley and Mary Shelley represented the romantic ideal not only in literature, but in their stormy lives and early deaths. Other romantic authors were the French Victor Hugo (who provoked a true pitched battle between the romantics and the classics at the premiere of Hernani), the Russian Aleksandr Pushkin, the Italian Alessandro Manzoni, the Spanish Mariano José de Larra or the American Edgar Allan Poe. The exploration of ancient popular traditions (folklore) produced collections of tales such as that of the Brothers Grimm, or the definitive version of the mythological cycle of Finland in the modern Kalevala compiled by Elias Lönnrot.