Languages of mexico

The languages of Mexico are the languages (and their linguistic varieties) spoken in a stable manner by those who inhabit the Mexican territory. In addition to Spanish, which represents the linguistic majority, at least sixty-eight indigenous languages are spoken in Mexico. Each of them has their respective linguistic variants or dialects, of which it is known that around three hundred and sixty-four are still spoken, in total.

The large number of languages spoken in the Mexican territory make the country one of the richest in linguistic diversity in the world. Pursuant to Article 4 of the General Law on the Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples, published on March 15, 2003, indigenous languages and the Spanish language were declared "national languages" due to their historical nature, for which reason they have the same validity throughout the Mexican territory.

In Mexico, the most widely spoken languages are Spanish and Nahuatl. The rest of the languages spoken in the country are below one million speakers. Among these, those with more than half a million speakers are Yucatec Maya, Tseltal, Tzotzil and Mixtec. Although there is no single established official language, Spanish and the 68 indigenous languages of the country are recognized as official languages of Mexico with the same value before the law.

During the viceregal period these linguistic varieties were maintained, consolidating Spanish as the predominant language among the upper classes and Nahuatl as the lingua franca. After the independence of Mexico, the need to cast all indigenous peoples into Spanish was raised, since linguistic diversity was seen as a difficulty in integrating them into national society. Until the XX century, the only language of teaching and administration was Spanish; The first attempts at literacy in indigenous languages were intended for students to learn to write and then continue the educational process exclusively in Spanish.

The population that speaks each of the national languages of Mexico is not precisely known. The 2010 Population and Housing Census, carried out by INEGI, indicates that around six million people speak an indigenous language, but the data corresponds only to people over five years of age. The indigenous ethnic population was estimated by the CDI at 12.7 million people in 1995, which was equivalent to 13.1% of the national population in that year (1995). In turn, the CDI maintained that, in 1995, the speakers of indigenous languages in the country numbered around seven million. The magnitude of the foreign language-speaking communities that have settled in the country as a result of immigration is also unknown.

Among the foreign languages spoken in communities established in Mexico for more than a generation are: English, spoken mainly in Baja California and Chihuahua by Mormons; Plodich, with around 70,000 Mennonite speakers, mainly in Chihuahua and Campeche; Chipileño Veneto, with approximately 7,000 speakers, mostly residents of Chipilo, Puebla; Romanesque, with an estimated 5,000 speakers, mainly in Oaxaca; the Afroseminola Creole, with 640 speakers in Coahuila; Kikapú, with 63 speakers in the same state; and several Iberian languages such as Catalan, Basque and Galician, with 64,000, 25,000 and 13,000 speakers, respectively.

History

Spanish is the most widely spoken language in the Mexican territory. Although there is no legal declaration that makes it an official language, its use in official documents and its hegemony in state education have made it a de facto official language and more than 98% of the total the more than 128.9 million inhabitants of Mexico use it, either as a mother tongue or as a second language.

The Spanish arrived in the territory now known as Mexico accompanying the Spanish conquistadores in the first decades of the XVI century. The first contact between the speakers of the indigenous languages of the region and the Spanish-speakers occurred as a result of the shipwreck of two Spanish sailors. One of them, Jerónimo de Aguilar, would later become an interpreter for Hernán Cortés.

Since the Spanish penetration in Mexican territory, the Spanish language was gaining a greater presence in the most important spheres of life. First, in New Spain, it was the main language of administration during the 17th century. However, the use of indigenous languages was allowed, and even Nahuatl was the official language of the viceroyalty since 1570. Notwithstanding the foregoing, it is estimated that, when the independence of Mexico was consummated, the number of Spanish-speakers barely exceeded 40% of the population, since the indigenous people continued to use their vernacular languages for the most part.

Viceregal Mexico

The relationship between Spanish and indigenous languages has gone through various moments since the Europeans arrived in America. In the Mexican case, numerous indigenous languages were the object of attention for the first evangelizing missionaries, who showed a particular zeal to learn the native languages and Christianize the Americans in their own languages. These and other intellectuals in the years after the Conquest produced the first grammars and vocabularies of languages such as Nahuatl, Maya, Otomi, Mixtec, and Purépecha. Thus, these languages were written for the first time in Latin characters. In contrast, numerous languages were lost before they could be recorded or systematically studied, as their speakers were quickly assimilated or physically extinct. In the case of dozens of languages that disappeared between the 16th and 19th centuries, all that remains are mentions of their existence in some writings and small vocabularies. It is estimated that around the XVII century, more than a hundred languages were spoken in Mexico.

Throughout the entire 19th century and most of the XX, the dominant policy regarding the national language was to make the speakers of indigenous languages Spanish. As can be deduced from the previous paragraphs, it was not a new decision, but the continuation of the trend imposed by colonial laws in the XVIIth century. The 19th century did not see much progress in the effort to incorporate the Indians into the «national society», through the suppression of their ethnic cultures (and with them, their languages). However, with the massification of public education that followed the Revolution, the proportion of Spanish speakers began to grow little by little. At the beginning of the XX century, Spanish speakers were already in the majority (approximately eighty out of every hundred Mexicans). Between 1900 and the year 2000, most of the indigenous peoples were hispanicized.

As explained before, at the time of speaking about Spanish, indigenous languages were the object of a process of marginalization and relegation to the domestic and community spheres of social life. Since their arrival in New Spain, some missionaries took on the task of recording the languages of the Indians, studying and learning them, with the purpose of helping a more efficient evangelization. With this last purpose, the missionaries of the Indies advocated for the teaching of the natives in their own language.

In accordance with this vision, Felipe II had decreed in 1570 that Nahuatl should become the language of the Indians of New Spain, in order to make communication between the natives and the peninsular colony more operational. However, in 1696, Carlos II, established that Spanish would be the only language that could and should be used in official affairs and the government of the viceroyalty. From the century XVII, the pronouncements in favor of the Castilianization of the Indians were more and more numerous. With this, the colonizers renounced their bilingual vocation, a vocation that initially led the missionaries and encomenderos to learn the languages of the natives. That need for bilingualism was then transferred to the actors who articulated the relations between the highest levels of government and the indigenous peoples, that is, the native elite embodied in the regional caciques.

Throughout the colonial period, Spanish and indigenous languages entered into an exchange relationship that led, on the one hand, the Spanish of each region to preserve words of indigenous origin in everyday speech; and indigenous languages to incorporate not only Spanish words, but also words from other Indian languages and especially Taíno.

Independent Mexico

After the consummation of the independence of Mexico, the dominant liberal ideology led those in charge of public education in the country to implement educational policies whose purpose was the Hispanicization of the indigenous people. According to its defenders, with the Castilianization the Indians would be fully integrated into the Mexican nation (a Creole nation, according to the nineteenth-century liberal project), on an equal footing with the rest of the citizens of the Republic. Except for the Second Mexican Empire, headed by Maximilian, no other government in the country was interested in the preservation of Indian languages during the 19th century, not even that of the only indigenous president the country has ever had: Benito Juárez.

In 1889, Antonio García Cubas estimated the proportion of speakers of indigenous languages at 38% of the total Mexican population. Compared to the 60% estimated by a population survey in 1820, the proportional reduction of native language speakers as a component of the population is remarkable. By the end of the XX century, the proportion dropped to less than 10% of the Mexican population. In the course, more than a hundred languages disappeared, especially those of the ethnic groups that inhabited northern Mexico, in the territory that roughly corresponds to the cultural macro-areas called Aridoamérica and Oasisamérica. However, despite the fact that in relative numbers the speakers of indigenous languages were reduced to a minority, in net terms their population increased. Currently they represent more than seven million people.

Before 1992, indigenous languages did not have any kind of legal recognition by the Federation. In that year, Article 2 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States was reformed, with the purpose of recognizing the multicultural character of the Mexican nation, and the obligation of the State to protect and promote the expressions of that diversity. Seven years later, on June 14, 1999, the Board of Directors of the Organization of Writers in Indigenous Languages presented to the Congress of the Union a Proposal for a Law Initiative on the Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Communities, with the purpose of opening a legal channel for the protection of native languages. Finally, the General Law on the Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples was promulgated in December 2002. This law contemplates mechanisms for the conservation, promotion and development of indigenous languages, but also a complex structure that hinders their realization.

Indigenous languages of Mexico

Mexico is the country with the largest number of Amerindian language speakers in the Americas, with a total of 65 living languages registered in 2010. However, in absolute numbers, the proportion of these linguistic communities (6.7%), is lower compared to countries like Guatemala (41%), Bolivia (36%) and Peru (32%) and even with Ecuador (6.8%) and Panama (10%). Except for Nahuatl, none of the languages indigenous people of Mexico has more than a million speakers. Nahuatl is the fourth indigenous language in the Americas by the size of its linguistic community, behind Quechua, Aymara and Guaraní.

Maps

List

Study

The study of indigenous languages began from the very arrival of the Spaniards in the territory currently occupied by Mexico. Some of the missionaries, because they were closer to the natives, noticed the similarities that existed between some of the languages, for example, Zapotec and Mixtec. In the 19th century, native languages were subject to a classification similar to that carried out in Europe for Indo-European languages.

This task was undertaken by Manuel Orozco y Berra, a Mexican intellectual from the second half of the XIX century. Some of his classificatory hypotheses were taken up by Morris Swadesh at the beginning of the XX century. The languages of Mexico belong to eight families of languages (in addition to some languages of doubtful affiliation and other isolated languages), of which the three most important both in number of speakers and in number of languages are the Uto-Aztecan languages, the Mayan and Otomanguean languages. One of the great problems presented by the establishment of genetic relationships between the languages of Mexico is the lack of ancient written documents that allow us to know the evolution of linguistic families. In many cases, the available information consists of a few words recorded before the disappearance of a language.

Such is the case, for example, of the Coca language, whose last vestiges are made up of some words that are suspected to belong rather to some variety of Nahuatl spoken in Jalisco. Other languages, such as Quinigua and Mamulique, the only original languages of Nuevo León of which there is a record, in addition to Coahuilteco, belong to the group of "unclassified languages". There are also cases such as the nakk-ita or mazapome (ita-nakk) language of Zumpango, which is scarcely documented and in 2020 there were still 3 speakers.

In 2020, the Catalog of National Indigenous Languages of the National Institute of Indigenous Languages was updated and the Na-Dené linguistic family and 4 languages of the group were recognized as part of the indigenous languages of Mexico.

Swadesh estimated that the number of autochthonous languages spoken in the Mexican territory reached one hundred and forty. Currently only sixty-five survive.

Classification

| Classification of indigenous languages of Mexico | |||||

| Family | Groups | Language | Territory | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yuto-Beauty Languages It is the most widespread family of Amerindian languages in Mexican territory. It is also the one with the largest number of speakers. | Southern Yuto-Aztecs | Tepimano | Papago | Sonora | |

| Low | Sonora, Chihuahua | ||||

| Tepehuán | Chihuahua, Durango | ||||

| Tepecano (†) | Jalisco | ||||

| [Taracahita Taracahites] | Tarahumarano | Tarahumara | Chihuahua | ||

| Guarijío | Sierra Madre Occidental | ||||

| Cahita | Yaqui | Sonora | |||

| May | Sonora and Sinaloa | ||||

| Opata-Eudeve | Opata (†) | Sonora | |||

| Eudeve (†) | Sonora | ||||

| Tubar (†) | Sonora | ||||

| Corachol-Zatecan | Corachol | Cora | Nayarit | ||

| Huichol | Nayarit and Jalisco | ||||

| Nahuateco | Pochuteco (†) | Oaxaca | |||

| Nahuatl | Mexico Valley, Sierra Madre Oriental, Veracruz | ||||

| Hokan languages Although this family is still discussed by linguists, it groups numerous languages spoken in the arid areas of Mexico and the United States. Some proposals include seri language, but in the most recent this language appears as an isolated language. Most of the Hokan languages have been extinguished, and others are about to disappear. | Yumano-cochimi languages | Yumanas | Paipai | Baja California Peninsula | |

| Cucapá | |||||

| Cochimí (Mti'pai) | |||||

| Kumiai | |||||

| Nak'ipa (†) | |||||

| 'Ipa juim (†) | |||||

| Kiliwa | |||||

| Cowards | Cochimí (†) | ||||

| Ignacieño (†) | |||||

| Borjeño (†) | |||||

| Tequistlateco-chontales | Chontal of Oaxaca | Oaxaca | |||

| Tequistlateco (†) | |||||

| Southern California Languages It is a set of spoken languages in the south of the Baja California peninsula. All are currently extinct. The low language documentation makes its classification doubtful. There has even been a doubt that all these languages have been part of the same family. Some linguists indicate that they may have had some distant relationship with the cochimi, and therefore they would be part of the Hokana family. | Guaicura (†) | Baja California Sur | |||

| Laimón (†) | |||||

| Aripe (†) | |||||

| Huichití (†) | |||||

| Cadégomeño (†) | |||||

| Didiu (†) | |||||

| Pericú (†) | |||||

| Isleño (†) | |||||

| Monguí (†) | |||||

| Allergy languages The only language spoken in Mexico is the kikapu, a language very close to the fox. The Kikapu tribe was established in Coahuila in the centuryXIXdue to the invasion of its original territory (Indiana) by whites. | Algonican languages | Central | Kikapu | Coahuila | |

| Omani languages | West Otomangue | Oto-pame-chinantecan | Oto-pame | Otomí | Centro de México |

| Mazahua | State of Mexico | ||||

| Matlatzinca | |||||

| Tlahuica | |||||

| Pame | |||||

| Jonaz | Guanajuato, San Luis Potosí, Querétaro | ||||

| Chinantecan | Chinanteco | Oaxaca and Veracruz | |||

| Tlapaneco - mangueano | Tlapaneco | Tlapaneco | Guerrero | ||

| Mangueano | Chiapaneco (†) | Chiapas | |||

| Eastern Otomangue | Popoloca-Zapotecan | Popolocano | Mazateco | Oaxaca and Veracruz | |

| Ixcateco | Oaxaca | ||||

| Chocho | Oaxaca | ||||

| Popoloca | Puebla | ||||

| Zapotecan | Zapoteco | Oaxaca | |||

| Chatino | Oaxaca | ||||

| Papabuco | Oaxaca | ||||

| Solteco | Oaxaca | ||||

| Amuzgo - Mixtecano | Amuzgo | Amuzgo | Oaxaca and Guerrero | ||

| Mixtecano | Mixteco | Oaxaca, Puebla and Guerrero | |||

| Cuicateco | Oaxaca | ||||

| Triqui | Oaxaca | ||||

| Toto-zoquenas languages The first classified attempts, such as Orozco and Berra, proposed an affinity between the Mixed-Zeroquean languages and the Ottoman languages. However, recent evidence points to the fact that the mixed-zoquean is related to the totonaco-tepehua. Also the language of the olmecas seems to be a form of mixed-zoquean. | Mixe-zoquean | Mixeano | Mixe de Oaxaca | Mixed varieties of the Juarez mountain range | Sierra de Juárez (Oaxaca) |

| Gulf Mix | Popoluca de Sayula | Veracruz | |||

| Popoluca de Oluta | Veracruz | ||||

| Mixe de Chiapas | Tapachulteco | Chiapas | |||

| Zoqueano | Gulf Zoque | Popoluca de Texistepec | Veracruz | ||

| Popoluca de Soteapan | Veracruz | ||||

| Zoque de los Chimalapas | Zoque de San Miguel Chimalapa | Chimalapas (Oaxaca) | |||

| Sta's Zoque. María Chimalapa | |||||

| Zoque de Chiapas | Variedades zoques de Chiapas | Poniente de Chiapas | |||

| Totonaco-tepehua | Totonacano | Totonaco | Sierra Madre Oriental (Veracruz and Puebla) | ||

| Tepehua | |||||

| Mayan languages Mayan languages (or mayances) are distributed in the southeast of Mexico and North of Central America. Insulated from this nucleus is the Huasteca language, which is spoken in the north of Veracruz and the east of San Luis Potosí. Some proposals have included the Mayan languages in the macro-Pentani group. In other hypotheses it has been pointed out that there might be some relationship between the Totonacana, Mixe-zoqueana and the Maya, although the proposal has not won many followers. Many of the spoken Mayan languages in Mexico have a small number of speakers. This is because several of these languages belong to Guatemalan groups that took refuge in Mexico during the civil war. They are currently regarded as national languages, such as the rest of indigenous languages. | Huasteco | Huasteco | Huasteca Region | ||

| Boymuselteco (†) | Chiapas | ||||

| Yucatecano | Yucateco - candy | Maya | Yucatan Peninsula | ||

| Lacandon | Chiapas | ||||

| Western Mayan | Cholano - tzeltalano | Cholano | Chol | Chiapas | |

| Chontal Tabasco | Tabasco | ||||

| Tzeltalano | Tseltal | Chiapas | |||

| Tsotsil | |||||

| Kanjobalano - Chuj | Kanjobalano | Kanjobal | |||

| Jacalteco | |||||

| Motozintleco or mochó | |||||

| Chujano | Chuj | ||||

| Tojol-ab'al | |||||

| East Mayan | Quicheano | Kekchí | Kekchí | Chiapas | |

| Pokom - quichean | Quiché | Chiapas and Guatemala | |||

| Cakchiquel | Chiapas and Guatemala | ||||

| Mameano | Teco-Mame | Mam | Chiapas | ||

| Teko | Chiapas | ||||

| Aguacateco-Ixil | Avocado | Chiapas and Veracruz | |||

| Ixil | Chiapas, Quintana Roo and Campeche | ||||

| Na-Dené languages | Atabascan | Apacheana | Lipán | Chihuahua and Coahuila | |

| Chiricahua | Chihuahua | ||||

| Mezcalero | Chihuahua and Coahuila | ||||

| Coyotero | Sonora | ||||

| Insulated languages Efforts have been made to group these languages into wider, yet unsuccessful families. The purépecha and the huave have been tried to attribute, without success, South American origins. The huave has also been related to the Puppet languages by Swadesh. Although very little information is available, it has been intended to relate the extinct coahuilteco to the hokana languages and the comecrudana languages. The seri has been included for a long time, without blunt evidence, to the great hokana hypothetical family. The cuitlateco appears in some classifications as part of the yuto-azteca family. Of the pericus is so little what is known and so many were their differences with the other languages of the Baja California peninsula, that neither the same missionaries of the centuryXVII they dared to establish relations between this language and the rest of the peninsulars. It is currently proposed that the pericus should be descendants of the first settlers of the region. | |||||

| Purepecha | Michoacán | ||||

| Huave | Oaxaca | ||||

| Cuitlateco (†) | Guerrero | ||||

| Coahuilteco (†) | Coahuila | ||||

| Seri | Sonora | ||||

| Unclassified languages In addition, there are a number of languages with very little documentation and references to languages of extinct peoples, which have not been classified for lack of information. See for example Unclassified Mexican Languages. | |||||

| Cotoname (†) | Tamaulipas | ||||

| Quinigua (†) | Nuevo León | ||||

| Solano (†) | Coahuila | ||||

| Naolano (†) | Tamaulipas | ||||

| Wonderful. (†) | Tamaulipas | ||||

| Chumbia (†) | Guerrero | ||||

From Spanish to bilingual intercultural education

In Mexico, "Castilianization" is understood as the process of adoption of the Spanish language by indigenous peoples. As noted above, its earliest de iure antecedents date from the 17th century, although it was not but not until the XIX century when it reached its maximum expression, in the context of the liberal Republic. With the generalization of public education, the Castilianization became more profound, although this did not result in the absolute abandonment of indigenous languages by their speakers. In other cases, the hispanicization was accompanied by physical extermination or ethnocide; special cases are the Yaquis (War of the Yaqui, 1825-1897), the Mayas (War of the Castes, 1848-1901) and the Californios (whose languages became extinct at the end of the XIX, after a long agony that began with the establishment of Catholic missions on the peninsula). The Apaches are a bit of a different case, although they resisted any efforts at hispanicization since the 17th century, they came into open conflict with Spaniards and Mexicans, and even with the other ethnic groups of the north (Tarahumaras, sumas, conchos, toboso). This was exacerbated when they were pushed west by the expansion of the United States, causing constant conflict in the northern states of Mexico and the southern United States (Apache War, throughout the 19th century).

Hispanicization had the purpose of eliminating the ethnic differences of the indigenous people with respect to the rest of the population, in order, ultimately, to integrate them into the nation under "equal" conditions. In Mexico, one of the main historical criteria for the definition of «indigenous» has been language (the «racial» criterion only disappeared from official discourse in the third decade of the century XX). For this reason, the strategies to induce the abandonment of indigenous languages were mainly aimed at the legal prohibition of their use in education, the factual prohibition of the exercise of teaching for indigenous people (when an indigenous person became a teacher, the government was in charge of relocating him to a community where his mother tongue was not spoken) and other similar ones.

Contrary to what the defenders of the Castilianization of the indigenous thought, their incorporation into the Spanish-speaking world did not mean an improvement in the material conditions of existence of the ethnic groups. The policy of hispanicization also ran into the shortcomings of the national educational system. It supposed that the students handled the Spanish language beforehand, although on many occasions it did not happen in this way. Many indigenous people who had access to public education during the first half of the 20th century in Mexico were monolingual, and being prohibited from using of the only language they spoke, they were unable to communicate in the school environment. On the other hand, the teachers were often indigenous whose command of Spanish was also precarious, which contributed to the reproduction of competitive deficiencies among the children. In view of the foregoing, in the 1970s, teaching in the indigenous language was incorporated in the refuge areas, but only as a transitory instrument that should contribute to a more effective learning of Spanish.

During the 1980s, bilingual education was the object of intensive promotion (in comparative terms with previous periods, since it has never constituted a mass system in Mexico). But even when the purposes remained the same (the incorporation of the indigenous people into the mestizo nation and the Castilianization), since then it has faced the shortcomings of the intercultural education system implemented in the second half of the 1990s. Know that teachers assigned to indigenous-speaking areas often do not master the indigenous language spoken by their students. On the other hand, it was only very recently that the Ministry of Public Education was concerned with the production of texts in indigenous languages, and only in some of them. The great linguistic diversity of Mexico, together with the reduced dimensions of some linguistic communities, have led the bilingual intercultural education system to focus only on the largest groups.

Dangered with extinction

Today, almost two dozen mother tongues are at risk of disappearing in Mexico. Listed below are some languages and dialect variants in danger of extinction.

- Chinanteco central bass

- Chontal of Oaxaca under

- Ayapaneco

- Chocho or chocholteco

- Ixcateco

- Lacandon

- Mochó

- Seri

- Nahuatl de Jalisco

- Tabasco Nahuat

- Tetelcingo Nahuatl

- Kiliwa

- Paipai

- Mixed southeast central

- Otomi de Ixtenco

- Otomí de Tilapa

- Misantla Totonaco

- Nahuatl mexicanero

Bilingualism and Diglossia

Most speakers of indigenous languages in Mexico are bilingual. This is the result of a long historical process in which their languages were relegated to the spheres of community and domestic life. Due to this, most of the indigenous people found it necessary to learn to communicate in Spanish both with the authorities and with the inhabitants of the mestizo populations, which became the nerve centers of the community networks in which they were integrated. their societies. The decline in the number of monolinguals among Mexicans who speak indigenous languages also contributed, as has been pointed out before, by the intensive educational campaign of a Castilian style.

Currently, there are language communities where less than 10% of their members speak exclusively the Amerindian language. This is the case of the linguistic community of the Chontales of Tabasco, who barely have 0.13% of the total monolingual. They are followed by the Yaquis (0.33%) Mazahuas —ethnic group from the state of Mexico, characterized by its early integration into the economic network of large cities such as Mexico City, D.F. and Toluca—, with 0.55% monolingual; and the mayos of Sonora and Sinaloa, with 1.78%. The communities with the largest number of monolingual indigenous people are also those where illiteracy is highest or whose traditional ethnic territory is located in the most marginalized regions of Mexico. Such is the case of the Amuzgos of Guerrero and Oaxaca, with 42% monolingual and 62% illiteracy; the Tseltals and Tzotsils of the Highlands of Chiapas, with 36.4% and 31.5% monolingual, respectively; and the Tlapanecos of the Mountain of Guerrero, with 31.5% monolingualism.

In recent years, some indigenous linguistic communities in Mexico have undertaken campaigns to rescue and revalue their own languages. Perhaps the exception are the Zapotecs of Juchitán, an urban center of Oaxaca where the Zapotec language has had a strong presence in all walks of life since the 17th century XIX. Movements to claim indigenous languages have taken place almost exclusively among those peoples who are highly bilingual or who in one way or another have inserted themselves into urban life. This is the case of the Yucatec Maya speakers, the Purépechas of Michoacán, the Nahuas of Milpa Alta or the Mixtecs who live in Los Angeles.

But in general, indigenous languages continue to be relegated to family and community life. A notable example is that of the Otomi of some regions of the Mezquital Valley. These groups have refused to receive instruction in their own language, since this is knowledge that can be learned "at home", and which will ultimately have no practical use in the future life of the learners. What parents request in cases of this type is that the literacy training of indigenous children be in Spanish, since it is a language that they will need to interact in places other than the community of origin. Because, although Mexican law has elevated autochthonous languages to the rank of national languages (better known to the common Mexican as dialects, a word used in the sense that "they are not true languages"), the country lacks mechanisms to guarantee the exercise of indigenous linguistic rights. For example, the published materials (texts or phonograms) in these languages are very few, the media do not provide spaces for their dissemination, except for some stations created by the defunct Instituto Nacional Indigenista (current National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples or CDI) in areas with a large population that speaks Indian languages; and because, finally, most of Mexican society communicates in Spanish.

Alochthonous languages of Mexico

Nearly two million speak foreign languages in combination with Spanish, many of them children of foreign immigrants, others are Mexicans who learned a foreign language in another country and the rest have acquired it in educational centers, for the performance of Your activities.

Although Spanish is the majority language in Mexico, English is widely used in business. Proficiency in the English language is a highly demanded characteristic in the search for professional employees, which has led to an exponential increase in the number of schools and institutes teaching English, and most private schools offer bilingual education and even what It has been called "bicultural". It is also an important language and is spoken as a second language after Spanish in border cities, but in these, as in some on the US side, it has mixed with Spanish creating a hybrid dialect called Spanglish. English is also the main language of the communities of immigrants from the United States on the coasts of Baja California and by Mormon settlers in the state of Chihuahua whose native language has been English since 1912. Although in practice English is a minority, there are newspapers in English such as: Gringo Gazette, Newsweek México, The News México and Mexico all Time, among others.

Recently, a community of athletes has been identified, mostly from Kenya (some of them already nationalized), who have decided to settle in Toluca, due to its strategic condition of proximity to the country's capital, its altitude, its sports facilities and their training places such as the slopes of the Nevado de Toluca, their concentration for training is daily, so it is now everyday to see them run in that area, chatting in English, their native language or Spanish.

There are no official data on the presence of other non-indigenous languages in Mexican territory. The Inegi includes them within the Other foreign languages category, although its final tables do not break down what these foreign languages are.

The Summer Institute of Linguistics estimated that by the mid-1990s there were 70,000 Plautdietsch speakers in the republic. Most of them settle in the semi-desert territories of Chihuahua, Zacatecas, Durango, Tamaulipas and Campeche. Of that community, less than a third also speak Spanish and are mostly male (adult women are monolingual), which can be explained by the isolation of the Mennonite community from its neighbors. Likewise, although it is estimated that the gypsy population in the country must have amounted to around 16,000 individuals; SIL estimates that some 5,000 of them speak the Romany or Caló language.

Today people in Chipilo still speak the Venetian language of their great-grandparents, whose own speakers often call them Chipileño. The Venetian variant spoken is Feltrino-Belunian. It is surprising that Chipileño Veneto has not been greatly influenced by Spanish, compared to how it has been altered in Italy by Italian. Although the state government has not recognized it, due to the number of speakers, the Veneto dialect is a minority allochthonous language in Puebla and an estimated 5,000 speakers. However, for a few years Chipileños have been working for the recognition of their language with talks with the INAH and above all with the cultural work that they carry out constantly despite the racism and discrimination they receive from the state authorities. and by the monolingual teachers who do not know the Veneto language of Chipilo.

As for the Iberian languages spoken in Mexico, there is a record of the use of Catalan, Basque and Galician. The speakers of these languages are mainly older people who came to Mexico because of the Spanish Civil War, and these languages are also spoken on a lesser scale by some of their children and grandchildren who are already Mexican by birth and by new Spanish migrants. who have arrived in the country in recent years. Catalan is the most widely spoken of these three in Mexico, according to sources in the Catalan community, which estimate some 64,000 speakers who are concentrated in Mexico City, Puebla, Quintana Roo, Baja California, Colima, Jalisco, and Sinaloa. Catalan is followed by Basque, with 25,000 speakers spread across Mexico City, the state of Mexico, Nuevo León, Coahuila, Jalisco, Colima, and Oaxaca. Finally, the third is Galician, with 13,000 speakers scattered mainly in the Mexican capital, the state of Mexico, Veracruz and Jalisco. Many of his words from Asturias and Extremadura remain present in the lexicon spoken by Mexicans, particularly those from the Central and Bajío regions. Another Iberian language spoken in Mexico is Ladino or Judeo-Spanish, the language of the Sephardic communities in Mexico.

There is an important Chinese community in the country, among which the Chinatown of Mexico City stands out, which has some 3,000 families of Chinese, other Asians and their descendants; and La Chinesca de Mexicali, with a population of about 5,000 Cantonese Chinese and their descendants; This community publishes a weekly newspaper in Chinese and Cantonese, the Kiu Lum, Cantonese and Mandarin is taught to children within the Association that the Chinese community of Mexicali built.

The Jewish community in Mexico City, mostly Ashkenazi, has promoted multilingual education among the children and youth of their community; Most of the students attend private schools where they are taught Spanish, English and Hebrew, where these subjects are taught in a mandatory way in order to obtain the school degree, as well as trilingual signage in said Mexican Jewish schools; in fact, there are also Hebrew-language newspapers for the parents of such students. Likewise, the program is designed for the recent immigration of Jews from other countries, who moved to Mexico and the Jewish community can offer an education according to the cultural vision of this community. In Chiapas, the fraylescano appeared in the Spanish viceregal era, a variant that combines voices from the old Spanish spoken by the first Spaniards with those of regional indigenous languages, such as Chiapas, Zoque and Maya, although also with some influence from the Ladino language.

The Frenchman left roots in the community of San Rafael, Veracruz since the arrival of a group of Frenchmen in 1833 with the idea of a better life in a generous climate. Currently, there are few descendants who speak it, although the French government finances an institution so that the French language continues to be spoken in that place. Later, during the period of the Second Mexican Empire, there was a wave of French, Belgians, Luxembourgers and Swiss who arrived in the country, who generally settled in the main cities of the time, leaving a great legacy on their way through Mexico; their descendants, a small community scattered throughout Mexico, have tried to maintain the language of their respective countries.

On the other hand, it is known about the presence of significant communities of speakers of German, Italian, Russian, Portuguese, Arabic, Ukrainian, Croatian, Maltese, Hungarian, Serbian, Bosnian, Vietnamese, Hebrew, Greek, Turkish, Swedish, Romanian, Chinese, Japanese, Filipino and Korean, although the SIL does not present data that allows to expose a figure about its weight in the statistics but the studies that are available are also estimated based on the data that these communities establish as well as those of the migration secretariat, which also provides approximate data. Many non-native indigenous groups in Mexico find themselves in the same situation and whose languages were not considered national by the country's legislation —something that did happen, for example, with the languages of the Guatemalan refugees. In this case, there is an important community of Quechua-speaking Ecuadorians and Peruvians settled in Mexico City, in the state of Mexico, in the state of Morelos and in the state of Puebla.

Between the United States-Mexico border, there is a presence of North American languages such as Kikapú, Kumiai and Pápago that are spoken between both countries and that have also been recognized as national languages. However, after the extermination or ethnocide of the various Apache tribes in Mexican territory. In the partial population census carried out by INEGI in 2005, non-native indigenous groups of Mexico were registered, among them 640 Afroseminola speakers, 37 Navajo speakers, 22 Mescalero Apache speakers, 12 Yavapai speakers in the states of Chihuahua, Sonora, Coahuila and Baja California with a very marked trilingualism among the indigenous people of the Mexico-United States border; In the case of the Navajos, it was due to commercial interests they have with Mexicans in the sale of wool or fodder for cattle, and in the case of the Apaches, it was due to the reintroduction of the American buffalo in the natural reserves of the Santa Helena and Boquillas canyon. del Carmen that are located on the southern banks of the Rio Grande where six indigenous families belonging to this ethnic group decided to live again in Mexican territory regardless of border problems as their ancestors once lived in the vast plains of the Chihuahuan desert. [citation required]

Although Mexico is recognized, according to its laws, as a multicultural country and determined to protect the languages of its diverse peoples, it has not given legal personality to the linguistic communities listed in this section. Mexican law does not contemplate protection or promotion for these languages, even when they form part of the identity of a (minority) group of Mexican citizens. It should be noted that, on this point, Mexican legislation is comparable with respect to the laws of most Western countries, where the languages of relatively recent immigrants, or populationally marginal, tend not to be considered as national languages at risk, and therefore, worthy of protection.[citation required]

Sign Languages

It is estimated that there are between 87,000 and 100,000 signers who practice Mexican Sign Language, between 400~500 Yucatecan Sign Language and ~13 Tijuana Sign Language.

Until now, there is no estimate of the number of American Sign Language signers, used by US and Canadian residents, as well as by children of Mexican emigrants.

There are also no estimates of who practices Spanish Sign Language and Guatemalan Sign Language.

Clusters of signers are found in Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Monterrey, as well as other smaller cities with significant signer communities. There are regional variations (80-90% lexical similarity across the country according to Faurot et al. 2001). There are important variations across age groups and people of completely different religious backgrounds.

Spanish Braille

In 2010, there was a total of 1,292,201 people with a degree of visual impairment, (27.2% of the total number of disabled people nationwide) so it is believed that only 10% of them are readers of the Braille alphabet Spanish, that is, about 130,000 approximately. The number of English Braille readers residing in the country is unknown.

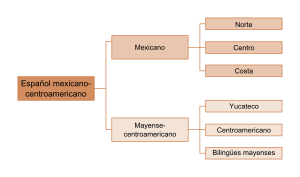

Mexican varieties of Spanish

The various dialects of Spanish spoken in America have been the object of study by linguists and philologists, with the purpose of understanding their peculiar characteristics. As a result of these studies, the Mexican dialects of Spanish have been treated as an independent group, or as part of the Mexican-Central American dialect group. According to Moreno Fernández, some of the features of the Mexican dialects of Spanish are shared with Central America, particularly the varieties spoken in southeastern Mexico. According to his proposal, Mexican-Central American Spanish can be divided into two large branches: Mexican and Mayan-Central American. Within the first fit the languages of the north, center and coastal areas of Mexico; while the second includes the varieties of Yucatán, Central America (including Chiapas) and the Spanish of bilingual speakers who are users of a Mayan language. Moreno Fernández's proposal is similar to the one elaborated at the time by Pedro Henríquez Ureña. According to Moreno Fernández, the five varieties of Mexican Spanish are characterized as follows:

- The English It is a series of talks that took root in the north of the country, a wide space where indigenous languages were virtually eliminated, and the repopulation was made with Europeans and indigenous people from the center of the country. Some of its most notable features are the articulation of [t implied] Like [CHUCKLES] - for example, Chihuahua pronounced [gili'wawa]— there is a weakening of vowels and diptongation of /e/ and /o/, and it also presents some lexical peculiarities.

- The Spanish from the center of Mexico is characterized by the weakening of vowels, the tension of [s] and [x] and the conservation of religious consonant groups as [ks] and [kt].

- The Spanish coastal Mexican shares several phenological traits with the Spanish speaking of the Caribbean basin. Among others, it presents the weakening of the [s] in the silabical elbow, [n] and generalized weakening of consonants at the end of the word, amen of loss of the [r] at the end of the infinitives.

- The Spanish yucateco is characterized by the strong influence of the Mayan language not only on the lexicon level, but also on the phenological and grammar solutions of the speakers. Some of these features are the glotalization of some consonants or the glorious cuts that do not exist in Spanish, the final position of [t implied] and [CHUCKLES] and the labial realization of [n] final (for example, bread joint [p]am]).

- The Central American is the variety of Spanish speaking used in Chiapas, related to those of the rest of Central America. Like the Yucateco Spaniard, the Central American coexists with various Mayan languages, but its influence is much lower. Some characteristics of Spanish spoken in Chiapas are the weakening of []] intervocálica, aspiration or weakening [x] and the monitoring of [n].

- The Spanish girl arose due to the migration of Mexican Spanish speakers to the U.S. border, the increase in the variety called Chicano Spanish has aroused a lot of interest in Mexican sociolinguistic research. Claudia Parodi heads these researchers with her studies of Chicano Spanish in Los Angeles.

Juan Miguel Lope Blanch carried out a more detailed internal classification of Spanish-speaking languages in Mexico that distinguishes ten dialectal regions throughout the Mexican territory. These are the Yucatan peninsula, Chiapas, Tabasco, Veracruz, the Oaxacan highlands, the center of the Neovolcanic Axis, the coast of Guerrero and Oaxaca, the northwestern varieties, the Mesa del Centro languages, and the northeastern region. This classification also contemplates other regions in formation such as the one that makes up Jalisco and Michoacán. Each of the varieties spoken in Mexico has certain characteristic features. In the case of Yucatecan Spanish, there is a strong influence of the Mayan language as an adstratus language; The Chiapas variety shares many characteristics with Central American Spanish, such as its "rural and conservative" character and the voseo, a phenomenon that has not been documented in other parts of Mexico. Tabasco speech is considered by Lope Blanch as a transition between the Veracruz and Yucatecan varieties, although other authors consider it within the group of Mexican coastal speech.

The x in Mexico

The reading of the ⟨x⟩ has been the reason for multiple comments from foreigners visiting the country. In general, any term of Spanish origin that requires it is written with ⟨x⟩ >exception, existence and many hundreds or thousands more. In all these cases, the ⟨x⟩ is pronounced as [ks], as stated in the standard rule. But in the case of indigenous voices, the rule is not as standardized nor is it necessarily known by the rest of the Spanish speakers, even though it has its origins in the speech and writing of the Iberian Peninsula of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

The spelling ⟨x⟩ has four different values in Mexico:

- The conventional one, [ks]as in the examples mentioned above or Tuxtla (de) Tochtlan, land of rabbits in Nahuatl), name of the capital of Chiapas, as well as of several towns in Veracruz.

- A value [CHUCKLES], pronounced as the,sh, of English, used in voices of indigenous origin as Mixiote (a stew prepared in the film covering the maguey's dick), Xel-Ha (name of a Maya ecological park) and Santa Maria Xadani (Zapotec population of Tehuantepec Isthmus). Like x⟩ Galician.

- A value [x], pronounced as,j,, for example: Xalapa (name of the capital of Veracruz), axolote (an amphibian of the lakes of the center of the country) or in the words Mexico and Mixe.

- A value [s]Like in Xochimilco (the famous lake of chilanga chimney) or as the Spanish xylophone voice.

Lexical characteristics of Spanish in Mexico

The Spanish spoken in Mexico is not homogeneous. Each region has its own idioms, as in the rest of the Spanish-speaking countries. However, it is possible to speak of some characteristics more or less common to all the regional dialects that make up what, to shorten, is called the Mexican dialect of Spanish. The abundance of words of Nahuatl origin is notable, even in areas where this language was not widely used, such as the Yucatan peninsula or northern Mexico. Many of these voices replaced those of the conquerors or those that were acquired by them in the Antilles, during the first stage of colonization. Many others were adopted because the Spanish lacked words to refer to some things that they were unaware of and that were present in the context of Mesoamerican civilization. Are examples:

- MetateNahuatl métatl, which designates a tripode flat stone on which nixtamal, chilies and anything susceptible to be converted into pasta are muted. All metate is accompanied by a stone known as "metallapil", "melapile" (Del náhuatl "metlapilli", by métlatl (metate) and pilli (son)) or "methlet hand" which is a long stone that serves as a roll to press the materials arranged in the metate, by action of human force.

- MolcajeteNahuatl molcáxitlwhich literally means container for stews, designates a cooking tool, also made of stone, in a concave and tripod form that is used to grind food and convert them into sauces with their respective Tejolote or hand of the molcajete. Some Spaniards of the time of the Conquest called it mortarits use and function is similar to that of that existing container in Spain.

- NixtamalNahuatl nextamalliliterally. corn empanada cooked with lime of pearl shell, is the name with which it is known in Mexico to the corn precooked with lime as a step prior to its grinding for the preparation of tortilla mass (see nixtamalization). The lime water used in the process receives the name of nexayote, najayote or nejayote (from Nahuatl) nexáyotl, which means ash water).

- PetateNahuatl pétatl. Literally designates a palm tissue that in the rest of Spanish-speaking America and Spain is known as a mat. Derivado de petate is the verb petatein Mexico means stretch the legsand in less colloquial mode, die.

Like the previous four, there are plenty of examples throughout Mexico. To this we must add the abundant place names of indigenous origin that became part of the daily speech of Spanish-speaking Mexicans and other voices of indigenous origin whose extension is of a regional nature and which constitute some of the differences between the local varieties of Mexican Spanish.

Apart from the lexicon, there are some phonological peculiarities of Mexican Spanish, generally, Mexicans tend to suppress the pronunciation of some unstressed vowels and elision in some words, especially when in a sentence a word ends with a vowel and the next one begins in vowel. Furthermore, in contrast to the natives of Spain, Mexicans tend to pronounce sets of two consonants in a row, such as [ks], [tl] and others (although the change of consonants is also frequent in some sociolects, as in [kl] instead of [tl], or [ks] instead of [ ps]). It should also be noted that, as in the rest of Latin America, Spanish speech in Mexico is characterized by the absence of the phoneme /θ /, which is replaced by /s/ since the two sibilants of century Spanish XVI converged on Latin American Spanish.

In Mexico there is no voseo, except in some southeastern regions, where three pronouns are used for the second person singular (tú, usted and vos ), with different semantic connotations. The distinction between tú and usted is general, the latter being used in formulas of respect or conversation with people whom one does not know. This is especially valid for the adult generations, since among young people this distinction tends to disappear. Similarly, while adults tend to refer to actions carried out by themselves with the pronouns one or yo, the use of you is becoming more and more general. for this type of construction, supposedly due to the influence of English. For this reason, when one could say that they have done such and such a thing, someone else will say that you do the same thing, but referring to themselves.[citation required]

Already entering the field of Anglicisms, it is accused that Mexican is one of the Spanish dialects with the largest number of voices of English origin. However, as Grijelmo points out, this is something relative, since there are some concepts for which Spanish-speaking Mexicans have developed castizas voices that, however, have been copied from English in other parts of the world. speak spanish. As an example of the above, in Mexico cars are parked, and not parked, as is done in Spain, where however cars are rented, while in Mexico the cars are rented (cars are rented).

Contenido relacionado

Inca empire

Praenomen

Unkulunkulu