Languages of italy

The languages of Italy constitute one of the richest and most varied linguistic heritages in Europe.

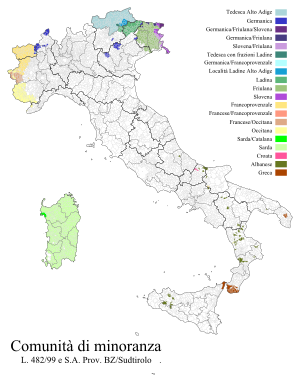

With the exception of some foreign languages linked to modern migratory flows, the languages spoken in Italy are exclusively of Indo-European stock and largely belong to the Romance language family. Linguistic minorities made up of the Albanian, Germanic, Greek and Slavic varieties also make up the linguistic landscape.

The Italian language is a Romance language derived from spoken Latin, especially from the archaic Tuscan variant, belonging to the Italo-Romance family of Italic languages. From the 14th century to the XIX, was, along with Latin, the main literary, cultural and administrative language in all the former pre-unitarian Italian States and, for this reason, in the year 1861, it continued as the official language of an Italy reunified into a single state. At the time of reunification, it was spoken but mainly by a minority of educated Italians, that is, by Italians who had been able to afford school education. It spread rapidly at the popular level thanks to the compulsory education and, from the 50s of the last century, also with the diffusion of the mass media. Currently, Italian is the mother tongue of 95% of the population residing in the country, that is, of almost all Italians and of a part of the foreigners registered in Italy. It is a group of 57,700,000 speakers out of a total population of about 60 million.

After Italian, the second language by number of speakers, in Italy, is another Italian-Romance variant of the same Italian family: Neapolitan (called "dialect", as well as the other Italian-Romance variants spoken in Italy, due to lack of standardization), spoken by some 11 million people in certain central-southern regions of the country.

In the territory of the Italian Republic the Italian language is often spoken together with one of its numerous dialects or, outside of central Italy, together with one of the various autochthonous regional languages, as well as, in specific areas of the country, with other languages officially recognized by the Italian State, be they Romance languages spoken exclusively in Italy (such as Friulan in Friuli and Sardinian on the island of Sardinia, which constitutes the largest linguistic minority in Italy in terms of number of speakers), be it Romance languages also spoken in other States (such as Franco-Provençal, spoken in certain alpine valleys of north-western Italy, or Alghero - a Catalan dialect - spoken exclusively in a Sardinian town); but also together with small non-Romance linguistic minorities circumscribed and limited to certain areas (such as South Tyrolean - German dialect - spoken in the province of Bolzano, Slovene, spoken in some border municipalities with Slovenia, a variant of ancient Greek - called griko - and arbëreshë - Italo-Albanian dialect - both spoken in some municipalities in southern Italy).

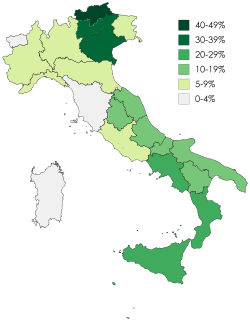

According to a recent study, 44% of Italians speak Italian exclusively or predominantly, 51% alternate Italian with a dialect or another language and 5% speak exclusively a dialect or another language other than Italian.

History

Ancient languages of Italy

Since prehistory in present-day Italy, a multitude of different languages have been spoken, most of them belonging to the Indo-European family, especially the Italic branch, subdivided in turn into the Osco-Umbrian languages (such as Umbrian, Oscan or Picenean) and Latino-Faliscan languages (such as Faliscan and Latin). Other languages belonging to the Indo-European branch were also spoken: some Paleo-Balkan languages, such as Venetic and Messapian, the latter related to the Illyrian languages, and in the northern region Lepontic and some Gaulish dialects, both belonging to the Celtic branch..

Likewise, other languages of non-Indo-European origin coexisted with these languages, highlighting Etruscan, but also Rhaetian (possibly related to the previous one), Old Ligurian, Picene from Novilara, Elymian (which is disputed if it was or not Indo-European) and Sican. On the islands of Sardinia and Corsica an autochthonous language of the place was spoken, the nurago.

Due to Punic and Greek colonization, Greek languages were also spoken - in southern Italy, known as Magna Graecia - and Punic and Greek in Sicily and Sardinia.

With the rise of Roman civilization, one of the languages belonging to the Italic branch: Latin, ended up imposing itself on all the others, later giving rise to the Romance languages and, within Italy, the current Italo-Romance and Gallo-Italic languages spoken in the country.

Origin of the languages of Italy

Many of the regions of Italy already had different linguistic substrata before the Romans spread the use of Latin throughout the peninsula: Northern Italy had a Celtic substratum (this part of Italy, before it was annexed to the territory from Roman Italy, it was known as Gallia Cisalpina), a Ligurian substratum and a Venetic substratum. Central Italy had an Etruscan and Italic substratum (of which Latin itself was a part), southern Italy Italic and Greek substratum, Sicily Italic, autochthonous, Greek and Punic substratum, while Sardinia autochthonous and Punic substratum.

Due to the political fragmentation of Italy, between the fall of the Western Roman Empire and its reunification in 1861, as well as the philosophical dilemma common to Italian intellectuals since the Middle Ages and known as Questione della lingua, there was considerable dialectal diversification, although the languages used for written communication and administration, in all the former pre-unitarian Italian states, were almost exclusively Latin (until the XIII), Latin together with Italian (since the XIV century until the XVI) and, from the middle of the XVI, exclusively Italian (with the sole exception of university scientific classes, which continued to be taught in Latin until the second half of the XVIII century, especially in some Italian States such as the Kingdom of Naples, the Kingdom of Sicily and the Papal States).

During this long period, the majority of the autochthonous population of the former Italian states spoke their own languages and dialects of the Italo-Romance group (in central and southern Italy) and of the satellite group of the former known as Gallo-Italic (in northern Italy). of Italy), that is, the local vernacular languages, on the other hand, the educated classes, used the Latin language and, from the XIV century , also the Italian (although full of Latin terms), adopted already in the XV century by the administration in some prestigious chancelleries of the time, such as the Duchy of Milan, the Republic of Venice, the Duchy of Ferrara, the Republic of Genoa, the Duchy of Urbino, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchy of Mantua, among others, and, from the XVI century, by the adm Inistration in the chanceries of all the other Italian States, such as the Kingdom of Naples, the Papal States, the Kingdom of Sicily, the Duchy of Savoy, etc.

At that time, also characterized by the presence of communes (or Italian city-states), especially in northern Italy, «...we will see the Tuscan dialect of Italian eclipsing its rivals, such as Attic Greek it eclipsed rival dialects of ancient Greek and, at the same time, being spread around the Mediterranean shores by Venetian and Genoese merchants and empire builders." As a result, a formal grammatical structure of Italian developed and the first Italian grammars and dictionaries. At the same time, especially after Pietro Bembo's linguistic reform, Italian ceased to be identified with vulgar Florentine and, thanks to the high level of its literature, established itself as one of the great languages of culture in the Europe of the time. Its cultural thrust was so select and appreciated that it prevailed as a written language over all other languages that were "...relegated to their strict condition." ion of orals". Likewise, while literate citizens used, from the modern age, Italian and Latin for written communication and as a means of formal expression by the bourgeoisie and intellectuals, the people did not literate used their own dialects and languages for oral communication and within an exclusively local, family and informal environment.

On the eve of the unification of Italy, that is, in the first half of the XIX century, Alessandro Manzoni, as all the great Italian writers of his time (Vittorio Alfieri, Ugo Foscolo, Giacomo Leopardi, etc.), continued to use a fairly conservative Italian language and at the same time enriched with neologisms, but which did not stray far from the classical Tuscan model. This same form of Italian was adopted as the definitive standardization of the national language, and all the other non-standardized forms of autochthonous oral expression (languages and dialects) suddenly became Italian dialects (but not of Italian). For this reason, today, the term "Italian dialects" is also still used, despite the fact that most of them do not derive from Italian, but from Vulgar Latin. A similar phenomenon occurred in France with one of the dialects of the d'oil language, spoken on the Ile de France, which became a national language in the 19th century XVI and, almost at the same time, in Spain, with Spanish, originally spoken in a limited area of Castilla la Vieja.

Dialects remained a fairly common speech among a large part of the Italian population until World War II. From that moment on, standard Italian, universally accepted for several centuries as a written, administrative, culture and study language, became the main language spoken also by the popular classes thanks to a progressive and better literacy and the diffusion of the mass media.

Current use

The solution to the so-called "language question" What had worried Manzoni came from the radio and, above all, from television. The popularization of these means of mass communication was one of the main factors that brought spoken Italian also among the most disadvantaged classes, or non-literate, throughout the country. During the same period, many southerners migrated north, just as many northerners left rural areas for cities, in both cases looking for work.

The powerful unions, wanting to keep workers together, successfully campaigned to promote literacy and the use of spoken Italian in informal contexts as well. This campaign allowed non-literate workers from all over the country to integrate more easily with each other using exclusively standard Italian. The large number of marriages between Italians coming from different regions, especially in the big industrial cities like Milan and Turin, gave rise, mainly in the north, to a generation that could only speak standard Italian and understand, only in part, some of the Italian languages. dialects of their parents.

As a result of these phenomena, regional languages are, today, more entrenched in the South (where the phenomenon of immigration did not occur), in rural areas (where there was less unionist influence) and among the older generations of the whole country. Not being able to speak Italian is, still today, a social stigma, as it is synonymous with illiteracy or low schooling.

Legal status

Italian is the official language of the country, although there is no article in the Italian Constitution that explicitly recognizes it as such. The express recognition is found in the statute of the Trentino-Alto Adige region, which is formally a constitutional law of the State. Article 99 of the statute says verbatim:

...[La lingua] Italian (...) è la lingua ufficiale dello Stato.

Translated into Spanish, Italian is the official language of the State.

In addition, the original of the Italian Constitution is written in Italian. On the other hand, in criminal and civil proceedings the use of Italian is mandatory.

Regarding the other languages, the Constitution expresses in the sixth article the following:

... The Republic shall protect, through appropriate rules, linguistic minorities.

Acting in accordance with that article, the Parliament has granted official status, at the regional or municipal level, with a 1999 law, to eleven other languages: Ladino, German, French, Catalan, Occitan, Franco-Provençal, Slovene, arbëreshë, griko, sardinian and friulan. These languages, in the areas where they are spoken, must be used on equal terms with Italian, must be taught in schools and must be used in RAI broadcasts. In addition to national laws, various regional statutes have recognized the official status of various languages in their territories. Thus, the already mentioned statute of Trentino-Alto Adige, recognizes, together with Italian, German (only in the province of Bolzano) and, the statute of the Valle d'Aosta region, gives co-official status to French. For its part, in the statute of Piedmont, Occitan, Franco-Provençal and Walser, a variant of German, are encouraged in specific alpine border valleys.

Number of speakers

| Group | Speakers | Original language | Language domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Napolitano | 11 000 | Neapolitan | Campania, south of Lacio, center and north of Apulia, Basilicata, Molise, Abruzos, south of Marcas and northern Calabria. |

| Sicily | 8 000 | Sicilian | Sicily, center and south of Calabria and south of Apulia. |

| Lombard | 7 000 000 | (Western and Eastern) | Lombardy, Western Trentino and Eastern Piemonte. |

| Véneto | 318 000 | Vèneto | Veneto, East Trentino and West Friul. |

| Sardo | 1 348 000 | Sardo | Center and South Sardinia (80.72 %) |

| Emiliano-Romañol | 1 250 000 | Emiliano-romañol | Emilia-Romaña and North of Marcas. |

| Friulano | 653 000 | Friulano | Friul-Venice Julia (43 %) and East Veneto. |

| Tyrolean | 251 000 | German Tyrolean | High Adigio (69.15 %). |

| Occitan | 178 000 | Occitan | Some municipalities in the provinces of Cuneo (4.76 %) and Turin (Piedmont) and a municipality in the province of Cosenza (Calabria). |

| Gallurés | 100 000 | Gallurés | Sácer Province, Sardinia. |

| Francoprovenzal | 90 000 | Francoprovenzal | Some municipalities in the province of Turin (Piedmont), some municipalities in the province of Aosta (Valle de Aosta) and two municipalities in the province of Foggia (Apulia). |

| Arbëreshë (Italoalbanese) | 80 000 | Arbëreshë | Some municipalities in the provinces of Cosenza, Crotona and Catanzaro (Calabria), three municipalities in the Potenza province (Basilicata), three municipalities in the province of Campobasso (Molise), three municipalities in the province of Palermo (Sicilia), two municipalities in the province of Foggia and one in the province of Taranto (Apulia), one municipality in the province of Avellino (Campania). |

| Ladino | 55 000 | Ladino | Some municipalities in the provinces of Bolzano and Trento (Trentino-Alto Adige) and some municipalities in the province of Belluno (Véneto). |

| Slovenian | 50 000 | Slovenian | Some municipalities in the provinces of Trieste, Gorizia and Udine (Friul-Venice Julia) |

| Catalan | 26 000 | Alghero | A municipality in the province of Sácer (Alguer), in Sardinia. |

| French | 20 000 | French | Aosta Valley (17.33 %). |

| Griko/Grecanico (Old Greece) | 20 000 | Griko/Grecanico | Some municipalities in the province of Regio de Calabria (Calabria) and some municipalities in the province of Lecce (Apulia). |

| Cimbro/Mocheno (Old Bavarian) | 3100 | Bavarian (Cimbro/Mocheno) | Two municipalities in the province of Vicenza (Véneto) and a municipality in the province of Trento (Trentino-Alto Adigio). |

| Croatian | 2600 | Croatian | A municipality in the province of Campobasso (Molise). |

Source: Ministero degli Interni del Governo Italiano/rielaborazione da Il Corriere della Sera. [citation required]

Classification of the languages of Italy

Romance Languages

The Romance languages proper to Italy belong to two main groups: the Italo-Romance group and the Gallo-Italic group, the latter considered the transition between the Italo-Romance languages proper and the Gallo-Romance languages; In addition to these two, there are languages from two other minority Romance groups that are isolated from each other: the Retorromance languages and the insular Romance languages. Most of these Romance Italian varieties are called dialetti (dialects, in Italian), not because they are dialects of standard Italian, but because for a long time they did not possess their own standardized form.

Over time, the use of the standard Italian language has acquired particular accents in each region, so these variants of Italian, with regional accents, are dialects in the usual sense, that is, they are dalects of Italian or derivatives from Italian, but these forms differ markedly from the regional languages, which are Romance languages to all intents and purposes, in most cases of the same family as Italian, but different from standard Italian. For this reason, the use of the term dialect is confusing and it is preferable to avoid it, since it can lead readers unfamiliar with the diglossic situation in Italy to confuse the terms.

Italo-Romance

Comprising varieties to the south and east of the Massa-Senigallia line, this branch includes Romanian, extinct Dalmatian, as well as Standard Italian and "central-southern Italian variants&# 3. 4; or Italo-Romance. Linguistically these Romance varieties are the closest to Italian and can be divided into four subgroups:

- Toscano: spoken in Tuscany, is (the basis of the Italian normative) and, in turn, of the Tuscan derives the corso and of this the Galician language, spoken in the north of Sardinia.

- Central Italian: is spoken in Umbría, center and north of Lacio, center of Marcas and a small part of Abruzos. Includes dialects such as Romanesque, marchigiano and Umbro.

- Napolitano: also known as "intermediate Southern Italian", is spoken in Campania, in Abruzos, in the center and south of Apulia, in Basilicata, in Molise, in the north of Calabria, in the south of Marcas and in the south of Lazio. Includes dialects like countrysideAbruzés, apulo-barés, tarentino, among others.

- Sicilian: also called "extreme Southern Italian", is spoken in Sicily, in the center and south of Calabria and in the south of Apulia. It includes the dialects spoken in Sicily, the center-meridal and the brothel.

Western Romances

Includes the varieties located to the north and west of the Massa-Senigallia line, in this branch includes Spanish, Portuguese, French, Catalan, Occitan, Arpitan, Romansh, Friulan, Ladino and the Gallo-Italic languages.

- Galloitálic languages: also called "Italian dialects of the north". Linguistically they are quite divergent of the Italian and the varieties of the center and the south, since they share certain phonetic evolutions with the French, the West, the Catalan, the Ladino and the Friulano. In addition, grammar can also have some significant differences with that of Italian. The Galician languages include:

- Piamontés: spoken exclusively in Piedmont.

- Lombardo: spoken in Lombardy, Eastern Piedmont, Western Trentino and in the Canton of the Tesino (joint with the Italian), in the so-called Italian Switzerland (in southern Switzerland).

- Ligur: spoken in Liguria.

- Emiliano-Romañol: spoken in Emilia-Romaña and in the north of Marcas.

- Emiliano

- Romañol

- Veneto: is spoken mainly in the Veneto, the Western Friul and the Eastern Trentin. It is the most divergent Galician language of the others and closer to the Italian language, so much that it is considered as a transition between the Galician languages and the italorromances languages themselves.

- Renewable languages.

- Friulano: is officially recognized and spoken in the autonomous region of Friul-Venecia Julia, as "language of the regional community", using in all social spheres.

- Ladino: is spoken in the mountains of the Dolomites, between the regions Trentino-Alto Adigio and the Veneto. It is officially recognized in the region of Trentino-Alto Adigio.

- Welsh tongues.

- French: it is co-official and spoken in the Aosta Valley, along with the Arpitán and the Italian.

- Arpitán: is spoken in the Aosta Valley and parts of Piedmont, along with the Italian.

- Occitanus languages.

- Occitano vivaroalpino: it is spoken in the Occitan Valleys of Piedmont, along with the Italian.

- Catalan alguerés: spoken in the city of Alguer (Cerdeña), together with the Sardinian and Italian, is officially recognized and protected by the Italian State. The Catalan was used exclusively in this city, mainly between the 14th and 18th centuries.

Insular Romances

- Sardo: is spoken in the center and south of Sardinia, is the most conservative romance language of all those derived from Latin and, at the same time, the most different of all Italian romance languages. It is recognized as the regional language of Italy and is spoken in Sardinia together with the Italian. The priestly language is consdered as the northernmost variant of the sardo, which presents some transitional features with the Italian-Roman languages and, more precisely, with the Gallluré variant of the Tuscan, spoken at the northern end of the island.

Judeo-Romances

- Judeoitalian: type of Jewish language, term coined in the middle of the centuryXX.. It is spoken by a small minority of Jews in Italy.

Germanic Languages

Standard German and Alto-Germanic varieties are spoken in certain specific areas in north-eastern Italy, that is, in some municipalities in the Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Veneto regions and, above all, in the province of Bolzano, in the Trentino region -Alto Adige. All the Germanic linguistic minorities of north-eastern Italy belong to the Bavarian group. Two municipalities with Cimbrian speakers are also found in Veneto. Finally, in Piedmont, there is a small Walser-speaking community, a variant of German of the Alemannic type, similar to the dialect spoken in the Swiss canton of Valais.

Albanian languages

In some municipalities of southern Italy and Sicily, there are several Arbëreshë-speaking linguistic minorities. Direct descendants of the Albanians who took refuge in Italy in the 15th and 16th centuries, after the death of Skanderbeg and the invasion of Albanian territory by the Ottoman Empire in 1478.

Greek Languages

In parts of the historical region of Magna Graecia (southern Italy), and more precisely in part of southern Calabria (Bovesia) and southern Apulia (Grecia Salentina), a dialect of ancient Greek called griko is spoken (or Grecanic). The main enclave is in the province of Lecce and the other in the province of Reggio Calabria.

Slavic languages

In Italy there are small Slavic linguistic minorities, of the Slovene type, in some municipalities of the provinces of Trieste, Udine, and Gorizia, in the region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, and in a very small Slavican-speaking community (Croatian dialect) in a single municipality in the province of Campobasso, in the Molise region.

Indo-Aryan Languages

In Italy, the gypsy people (itinerants) are mostly from the Sinti group and speak two languages of Indian origin. In the north and center of Italy, the Sinti language, while, in Abruzzo and in the south of the peninsula, the Romany language; both groups of Italian Gypsies are known, in the Italian language, simply as zingari (from the Greek atziganoi, 'Egyptians').

Gallery

Contenido relacionado

Spanish dictionary

Abesive case

Cockney