Kosovo history

The History of Kosovo alludes to the historical context of the Kosovo region, in the Balkans. Archaeological studies have established that its territory was inhabited in the stone age. The oldest inhabitants were the Illyrians, Thracians and ancient Greeks. This territory was known in antiquity as Dardania and, from the 1st century B.C. C., it was part of the Roman province of Mesia and, later, of the Byzantine empire. During the 6th and 8th centuries AD, the Slavs settled on the peninsula and Kosovo then became a Byzantine frontier province until the 11th century. Stefan Nemanja officially incorporated it into the Serbian state at the end of the XII century, although it was part of the Serbian medieval states, mainly Raška (Serbian: Рашка) from 700 to 1455, when it was conquered by the Ottoman Empire.

In the feudal period, from the 12th century to the Ottoman conquest, mining, crafts, animal husbandry and agriculture were developed. The communities of Novo Brdo and Trepča were important mining centers for the production of lead, silver and gold. Kosovo was the scene of many battles between the Serbian and Ottoman armies. The most famous of these is known as the 'battle of Kosovo', fought in 1389 at Gazimestan, a field near Pristina. After the Serbian defeat, Kosovo remained part of the domain of the Despotate of Serbia, a state considered a vassal of the Ottoman Empire. After his fall in 1459, the Turks established their direct rule over the province, founding a feudal military form of government like the rest of the empire. It should be noted that, until the end of the 16th century, Ottoman population censuses in Kosovo (and, before them, censuses Serbs) do not record the existence of a single inhabitant arnauta (name by which, from the XVII century, it was known -- and still known - Albanians, in what are now the territories of Montenegro and Serbia). Under Turkish rule (1459-1912), Kosovo stagnated in all respects. The war, economic difficulties and political changes resulted in a large-scale emigration of its population. From the beginning of the occupation until the end of that period, the inhabitants of the province carried out many insurrections that were suppressed "manu militare".

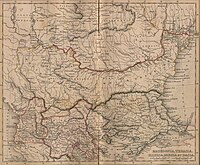

The Ottoman vilayate of Kosovo dates from 1875, its borders being significantly different from those of the present-day province. In 1912, the territory was reincorporated into Serbia and, as part of Serbia, it became an integral part of Yugoslavia in 1918. Kosovo gained some autonomy in 1963 under Tito's rule and, in 2006, with the dissolution of Serbia and Montenegro it remained being part of the Republic of Serbia. Thus, modern Kosovo has only existed as a political or territorial entity since 1946, when it received the status of an autonomous province.

On February 17, 2008, the Kosovar Provisional Self-Management Institutions unilaterally declared independence, with which they sought to split off, from the rest of Serbia, this territory inhabited for the most part by the Albanian minority. The creation of a new State called the Republic of Kosovo has been carried out to the detriment of Serbia under the supervision of the United States and several member countries of the European Union, although with partial international recognition as such.

Ancient History up to the Byzantine Conquest

The area of Kosovo in the Neolithic was in the area of the Vinča-Turdaş culture (Western Balkans, with black and gray pottery). The Bronze Age begins around the 20th century BC. C. and the Iron Age begins approximately in the 13th century BC. C. Bronze and Iron Age tombs have been found only in Metohija and not in Kosovo.

The territory comprised the eastern parts of the kingdom of Illyria in the 4th century BCE. C., being border with Thrace. At the same time, it was inhabited by the Thraco-Illyrian tribes of the Dardanians and the Thracian tribe of the Tribalians.

Illyria was conquered by Rome in the year 160 B.C. C. and became the province of Illyricum in the year 59 BC. C. The Kosovo region was part of Mesia Superior in the year 87 AD. C. (or alternatively it was divided between Dalmatia and Moesia, a view that is supported by some archaeological evidence). Moesia Superior was later reorganized by Diocletian (after 284) into smaller provinces, later being divided into Dardania, Mesia Prima, Dacia Ripensis, and Dacia Mediterranea. Dardania's capital was Naissus. The Roman province of Dardania included eastern parts of modern Kosovo, while its western part belonged to the Roman province of Praevalitana, whose capital was Doclea.

Justinian I, who assumed the throne of the Byzantine Empire in 527, oversaw a period of Byzantine expansion into former Roman territories, reincorporating the area of Kosovo into the Empire. He is often referred to among historians as the last Roman emperor because Latin was his native language and because he was the last emperor to make a serious attempt to reunify the Latin West with the East.

Slavic migrations reached the Balkans between the VI and VII. The area was reincorporated by the Byzantine Empire in the mid-IX century.

Kosovo in the Middle Ages (from 850 to 1455)

Bulgarian Empire (from 850 to 1014)

The region was incorporated into the Bulgarian Empire during the reign of the Presian Khan (836-852). Several churches and monasteries were built after the Christianization of Bulgaria in 864. It remained within the limits of the Bulgarian Empire for 150 years until 1018, when the country was invaded by the Byzantines after half a century of intense fighting. According to the De administrando imperio, a scholarly work of the Byzantine emperor of the X century Constantine VII, the lands populated by Serbs were in the northwest of Kosovo and the region was Bulgarian.

During the Bulgarian uprising against the Byzantine Empire (1040-1041), Kosovo was liberated for a short period and, during Georgi Voiteh's uprising in 1072, Peter III was proclaimed Emperor of Bulgaria in Prizren, from where the Bulgarian army He marched towards Skopje.

In the early 13th century, Kosovo was reincorporated into the restored Bulgarian empire, but Bulgarian control waned after the Death of Emperor Ivan Asen II (1218-1241).

Byzantine Empire (from 1014 to 1180)

Byzantine control was later reasserted by Emperor Basil II. By then, Serbia was not a unified empire: several small Serbian kingdoms sprawled in the north and west of Kosovo, including Rascia (Raska, modern central Serbia) and Doclea (Duklja, Montenegro) were the strongest. In the 1180s, Serbian ruler Stefan Nemanja took control of Doclea and parts of Kosovo. His successor, Stefan Prvovenčani took control of the rest of Kosovo by 1216, creating a state and incorporating most of the area that is now Serbia and Montenegro.

Serbia (from 1241 to 1455)

Kosovo was assimilated by Serbia at the end of the 12th century and became part of the Serbian Empire from 1346 to 1371. In 1389, in the famous Battle of Kosovo, the army led by the Serbian prince Lazar Hrebljanovic was defeated by the Ottoman Turks, who finally took control of the territory in 1455.

During the rule of the Nemanjić dynasty, many Orthodox churches and monasteries were built throughout Serbian territory. The Nemanjić rulers alternately used Prizren and Priština as their capitals. Large estates were given to monasteries in western Kosovo (Metohija). The most prominent churches in Kosovo – the Peć Patriarchal Monastery, the Gračanica Church and the Visoki Dečani Monastery (near Decane) – were built during this period. Kosovo was economically important, while Pristina was a prominent trade center on the routes leading to the ports on the Adriatic Sea. Likewise, mining was an important industry in Novo Brdo and Janjevo, which had their own communities of Saxon émigré miners and Ragusan merchants.

The ethnic composition of the Kosovar population during this period included Serbs and Vlachs, in addition to a token number of Greeks, Armenians, Saxons and Bulgarians, according to the statutes of the Serbian monasteries or chrysobulls. Most of the names in the statutes are Slavic, not Arnaut or Albanian, which has been interpreted as evidence of the overwhelming Serb majority. This claim seems to be supported by the Turkish cadastral censuses (defter) of 1455, which took religion and language into account[citation needed] and found a Serb majority.

Ethnic identity in the Middle Ages was somewhat fluid across Europe and people do not appear to have rigidly defined themselves by a single ethnic identity. Those of Slavic origin, particularly of Serb background, appear to have been the dominant population culturally and were a demographic majority as well.

In 1355, the Serbian state fell apart after the death of Tsar Stefan Uroš IV Dušan Nemanjić and dissolved into fiefs, with feuds between them. The timing was right for Ottoman expansion. The Ottoman Empire took the opportunity to exploit Serbian weakness and invade.

Kosovo Battles

First Battle of Kosovo

The First Battle of Kosovo took place at Kosovo Polje on June 28, 1389, when Serbian Knyaz (prince) Lazar Hrebeljanović assembled a coalition of Bosnian Serb Christian soldiers, Magyars and a troop of Saxon mercenaries. Sultan Murad I also assembled a coalition of soldiers and volunteers from the neighboring countries of Anatolia and Rumelia. There are no exact sources indicating the number of contenders, but the most reliable sources indicate that the Christian army was outnumbered by the Ottomans.[citation needed] The combined number of the two armies must have been less than one hundred thousand soldiers. The Serbian army was defeated and Lazar was killed, although Murad I was also killed by Miloš Obilić. While the battle has entered legend as a major Serb defeat, opinion at the time was divided as to whether it was a Serb defeat, a draw, or even a victory (by the time the news broke in Paris, the bells of the Cathedral of Notre Dame were blown up) because Serbia maintained its independence and sporadic control over Kosovo until final defeat in 1455, after which Serb became part of the Ottoman Empire. That year, the fortress of Novo Brdo, important at the time due to its rich silver mines, was besieged for forty days by the Ottomans, who achieved their capitulation and occupied it on June 1, 1455.

Second Battle of Kosovo

The Second Battle of Kosovo was fought over the course of two days in October 1448, between Hungarian forces commanded by John Hunyadi and an Ottoman army led by Murad II. Significantly larger than the first battle, with both armies doubling those of the first battle, the result was the same and the Hungarian army was defeated in battle and driven from the ground. While the loss of the battle was a setback for those resisting the Ottoman invasion of Europe, it was not a crushing blow to the cause. Hunyadi was able to maintain the Hungarian resistance against the Ottomans throughout his life.

Importance

Both battles were significant in the joint resistance against the Ottoman advance through the Balkans. The First Battle of Kosovo sealed the fate of the Serbian resistance and became a national symbol of heroism and the admirable 'fight against all odds'.

Although he lost the Second Battle of Kosovo, Hunyadi was ultimately victorious in his resistance and defeat of the Ottomans in the Kingdom of Hungary. Skanderbeg also succeeded in resisting in his Albanian homeland, a cause that was lost upon his death in 1468. Both leaders were important (as was the Wallachian leader Vlad Draculea) as their resistance gave Austria and Italy more time to prepare. for the Ottoman advance.

Ottoman Empire (from 1455 to 1912)

The Ottoman Empire brought Islam and subsequently created the Kosovo Vilayate as one of the Ottoman territorial entities. The Ottoman rule lasted for around 500 years, during which the Ottomans exercised supreme power in the region. Many Slavs accepted Islam and served under Ottoman rule. Kosovo was temporarily taken by Austrian forces during the 1683-1699 war with the help of the Serbs, but they were defeated and had to withdraw shortly thereafter.

In 1690, Serbian Patriarch Peć Arsenije III, who had previously escaped certain death, led thirty-seven thousand Kosovo families to evade Ottoman wrath as Kosovo had recently been retaken by the Ottomans. The people who followed him were mostly Serbs. Due to Ottoman oppression, migrations of Orthodox from the Kosovo area continued throughout the 18th century. Many Arnauts adopted Islam, while only a small minority of Serbs did.

In 1766, the Ottomans abolished the Peć Patriarchate and the position of Christians in Kosovo was greatly reduced. They lost all previous privileges and the Christian population also bore the full brunt of the Empire's extensive wars and being blamed for their losses.

The territory of the current province was for centuries ruled by the Ottoman Empire. During this period, various administrative districts (known as sanjaks) that were ruled by the sancakbey (roughly equivalent to "district lord") had included parts of the territory as their own. Despite the imposition of Muslim rule, large numbers of Christians continued to live and sometimes prosper under the Ottomans. A process of Islamization began shortly after the start of Ottoman rule, but it took a considerable amount of time, at least a century, to bear fruit, initially concentrating on villages. A major motivation for conversion was probably economic and social, since Muslims had considerably more rights and privileges than Christians; however, Christian religious life continued, although the churches were largely abandoned by the Ottomans, as both the Serbian Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church and their congregations faced high levels of taxes.

Around the 17th century, there is evidence of the existence and increase of the Arnaut population that was initially concentrated in Metohija. It is argued that it was the result of Turkish-sponsored migrations from the south-west (i.e., from modern Albania) and that the migrants brought Islam with them. Several historians[citation needed] believe that there is the possibility of a pre-existing population of Catholic Albanians in Metohija who, for the most part, converted to Islam.

In 1689, Kosovo was greatly destabilized by the Great Turkish War (1683-1699), in one of the pivotal events in Serbian national mythology. In October 1689, a small Habsburg force under Margrave Ludwig of Baden invaded the Ottoman Empire, going as far as Kosovo, following their earlier capture of Belgrade. Many Serbs pledged allegiance to the Austrians, and some joined Baden's army. This was not a universal reaction; many other Arnauts fought alongside the Ottomans to resist the Austrian advance. The next, a massive Ottoman counter-attack forced the Austrians to fall back on their fortress at Niš, then to Belgrade, and finally across the Danube into Austria.

In 1878, one of the four Arnaut-inhabited vilayates that formed the League of Prizren was the Vilayate of Kosovo. The League's goal was to resist both the Ottoman rule and the incursions of the newly emerging Balkan nations.

In the year 1910, an Albanian insurrection broke out in Priština, which was possibly surreptitiously aided by the Young Turks to put pressure on the Sublime Porte. Soon after, it spread throughout the Kosovo vilayate, lasting for three months. The Sultan visited Kosovo in June 1911 during peace talks and covered all Albanian-inhabited areas.

Albanian National Movement

The Albanian national movement was inspired by several reasons. Outside of the National Renaissance that had been promoted by Arnaut activists, political reasons were an important factor. In the 1870s, the Ottoman Empire experienced a tremendous contraction in terms of its territory due to its defeats in the wars against the Slavic monarchies of Europe. During the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878), Serbian troops invaded the northeastern region of the Kosovo province and deported 160,000 Arnauts from 640 towns. In addition, the signing of the Treaty of San Stefano marked the beginning of a difficult situation for the Albanian people in the Balkans, whose lands had to be ceded by Turkey to Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria.

Fearing the partition of the Arnaut-inhabited lands among the newly founded Balkan kingdoms, the Albanians established their League of Prizren on June 10, 1878, three days before the Berlin Congress reviewed the decisions made at San Stefano. Although the League was founded with the support of the sultan who hoped the Ottoman territories would be preserved, the Arnaut leaders were quick and effective enough to turn it into a national organization and, eventually, a government. The League had the backing of the Italian-Albanian community and had become a unifying factor for the religiously diverse Albanian population. During its three years of existence, the League sought to create an autonomous Albanian state within the Ottoman Empire, raised an army and fought a defensive war. In 1881, a provisional government was formed to administer Albania under the presidency of Ymer Prizreni, assisted by prominent ministers such as Abdyl Frashëri and Sulejman Vokshi. However, the military intervention of the Balkan States, the Great Powers, as well as Turkey divided the Arnaut troops into three fronts, which led to the end of the League.

Kosovo was then home to other Albanian organizations, the most important being the Peja League, named after the city in which it was founded in 1899. It was led by Haxhi Zeka, a former member of the League. of Prizren, and shared a similar platform in search of an autonomous Albania. The League ended its activities in 1900 after an armed conflict with the Ottoman forces. Zeka was assassinated by a Serb agent in 1902, aided by Ottoman authorities.

Albanian independence and Balkan wars

The demands of the Young Turks at the turn of the 20th century aroused support among Albanians, who were expecting an improvement of their national situation, fundamentally, the recognition of their language for official use and education. In 1908, twenty thousand armed Albanian peasants gathered in Uroševac to prevent foreign intervention, while their leaders Bajram Curri and Isa Boletini sent a telegram to the sultan demanding the promulgation of a constitution and the opening of parliament. The Albanians received none of the benefits promised by the Young Turks' victory. Considering this, Albanian highlanders staged an unsuccessful uprising in Kosovo in February 1909. Adversity increased after an oligarchic group took over the Turkish government later that year. In April 1910, the armies commanded by Idriz Seferi and Isa Boletini rebelled against the Turkish troops, but were eventually forced to withdraw after inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy.

20th century

Balkan Wars

In 1912, during the Balkan Wars, most of Kosovo was occupied by the Kingdom of Serbia, while the region of Metohija (Albanian: Dukagjini) was occupied by the Kingdom of Montenegro. Following the First Balkan War of 1912, Kosovo was internationally recognized as part of Serbia and northern Metohija as part of Montenegro in the London Treaty in May 1913. In 1918, Serbia became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

Interbellum and World War II

The 1918-1929 period of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes saw an increase in the Serb population in the region, accompanied by a decline in the non-Serb population. In the Kingdom, Kosovo was divided into four counties, three of which were part of the Serbian entity: Zvečan, Kosovo, and southern Metohija; and one from Montenegro: northern Metohija.

In 1929, Kosovo was divided into the provinces of Zeta Banovina in the east, with the capital at Cetinje; Vardar Banovina in the southeast, with the capital in Skopje; and Morava Banovina, with the capital at Niš.

The partition of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by the Axis Powers from 1941 to 1945 gave most of the territory to Italian-occupied Greater Albania and a smaller part to German-occupied Serbia and Greater Bulgaria. During the German occupation, thousands of Kosovar Serbs were expelled by armed groups of Albanian collaborators and, in particular, by the Vulnetari militia. Exactly how many people fell victim to it is still unknown, but Serb estimates range from 10,000 to 40,000 with 70,000 to 100,000 expelled.

Kosovo in the second Yugoslavia (from 1945 to 1996)

After the end of the war and the establishment of the communist regime of Tito, Kosovo was granted the status of an autonomous region of Serbia in 1946 and became an autonomous province in 1963. The communist government did not allow the return of many of the Serb refugees, while continuing the imprisonment and murder of self-styled patriotic Albanians (such as Shaban Polluzha) culminating in the Tivar massacre, where between 3,000 and 4,000 Kosovar Albanians resisting the Yugoslav regime are said to have been killed with machine guns (Tito forgave many Albanians identified as German collaborators during the Nazi occupation, which was not forgotten by the Serbs expelled from Kosovo, who suffered the "first" ethnic cleansing at their hands).

With the approval of the Yugoslav constitution of 1974, Kosovo acquired virtual self-government. The government of the province had applied the Albanian curriculum in Kosovo schools: obsolete and surplus textbooks from Enver Hoxha's Albania were obtained and put to use.

Throughout the 1980s, tensions between the Albanian and Serb communities in the province escalated. The Albanian community favored greater autonomy for Kosovo, while the Serbs supported stronger ties with the rest of Serbia. There was little appetite for unification with Albania itself, which was ruled by a Stalinist government and had considerably worse standards of living than Kosovo. At the beginning of March 1981, Kosovar Albanian students organized protests demanding that Kosovo become a republic within Yugoslavia. These protests quickly escalated into violent riots "involving twenty thousand people in six cities", which were harshly contained by the Yugoslav government. Two thousand students were poisoned when the water pipes that supplied their dormitories were contaminated.

Serbs living in Kosovo were discriminated against by the provincial government (the term 'ethnic cleansing' was coined to designate these actions), especially by local police authorities who failed to punish reported crimes against the Serbs. The atmosphere was increasingly harsh in Kosovo. When a Serbian farmer, Đorđe Martinović showed up at a Kosovo hospital with a bottle in his rectum after being robbed on his land by masked men, 216 prominent Serbian intellectuals signed a petition declaring that "the Đorđe Martinović's case has come to symbolize the plight of all Serbs in Kosovo."

Perhaps the most politically explosive complaint made by Serbs in Kosovo was that they were being neglected by the communist authorities in Belgrade. In August 1987, during the last days of communist rule in Yugoslavia, Kosovo was visited by Slobodan Milošević, then a rising politician, who appealed to Serbian nationalism to further his career. Having called a large crowd to a rally commemorating the Battle of Kosovo, he promised the Kosovo Serbs that "no one should dare hit them." and he became an instant hero to the Kosovo Serbs. By the end of the year, Milošević was in control of the Serbian government.

In 1989, the autonomy of Kosovo and the northern province of Vojvodina was drastically reduced by a referendum across Serbia. This referendum implemented a new constitution that allowed for a multi-party system, introduced freedom of expression, and promoted human rights. Even if in practice it was subverted by the government of Milošević who resorted to rigged elections, controlled most of the media, and was accused of violations of the human rights of his opponents and national minorities, this was a step forward for the constitution. previous communist. It significantly reduced the rights of the provinces and allowed the Serbian government to exercise direct control over many previously autonomous areas. In particular, the constitutional changes handed over control of the police, the judicial system, the economy, the education system, and language policies to the Serbian government. The new constitution was strongly opposed by many of Serbia's national minorities, who saw it as a means of imposing centralist laws based on ethnicity on the provinces.

Kosovar Albanians refused to participate in the referendum, considering it illegitimate; however the new constitution had to be ratified by the Kosovo assembly. Although the assembly was initially opposed to the constitution, but in March 1989, when the assembly met to discuss the proposals, tanks and armored cars surrounded it and delegates were forced to accept the amendments.

1990s

After the constitutional changes, the parliaments of all Yugoslav republics and provinces, which until then had only deputies from the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, were dissolved and multi-party elections were held for them. The Kosovar Albanians refused to participate in the elections and held their own elections. As the electoral laws required (and still require) a turnout of more than 50% of the voters, the Kosovo parliament could not be constituted.

The new constitution abolished the official media of the individual provinces, integrating them into the official media of Serbia, although some Albanian-language programs were still maintained. Albanian-language media in Kosovo were suppressed. Funding was withdrawn from state media, including the Albanian-speaking ones in Kosovo. The constitution only allowed the creation of private media; however, its operation was very difficult due to high rents and restrictive laws.

Albanian-language public television or radio was also banned in Kosovo; however, private Albanian media appeared, probably the most famous of which was Koha Ditore, which was allowed to operate until late 1998, when it was shut down after publishing a calendar that was syndicated as glorifying ethnic Albanian separatists.

The constitution also transferred control over state-owned companies to the Serbian government (at the time, most companies were state-owned and de jure still are). In September 1990, the Western media claimed that some 123,000 Albanian workers were sacked from their government and media jobs, as well as teachers, doctors, and workers in government-controlled industries, sparking a strike. general and social unrest. Some of those who were not fired resigned out of solidarity and refused to work for the Serbian government. Although the dismissals were widely seen as a purge of ethnic Albanians, the government maintained that it was simply getting rid of old communist directors.

The Albanian curriculum and textbooks were revoked and new ones were produced. The curriculum was basically the same as Serbian and all other nationalities in Serbia, except that education was about and in the Albanian language. Education in Albanian was withdrawn in 1992 and reinstated in 1994. At the University of Pristina, which was seen as a center of Kosovar Albanian cultural identity, education in the Albanian language was abolished and Albanian teachers were laid off en masse. Albanians responded by boycotting state schools and setting up an unofficial parallel system of education in the Albanian language.

Kosovar Albanians were outraged by what they saw as an attack on their rights. Following massive riots and social unrest on the part of Albanians, as well as explosions of intercommunal violence, in February 1990, a state of emergency was declared and the presence of the Serbian army and police was significantly increased.

Unofficial elections were held in 1992, overwhelmingly electing Ibrahim Rugova as "president" of a self-proclaimed Republic of Kosovo; however, these elections were not recognized by the Serbs or any foreign government. In 1995, thousands of Croatian Serb refugees settled in Kosovo, further deteriorating relations between the two communities.

Albanian opposition to the sovereignty of Yugoslavia and, especially, Serbia had come to the fore in riots (in 1968 and March 1981) that took place in the capital, Pristina. Initially, Ibrahim Rugova advocated nonviolent resistance, but later opposition took the form of separatist agitation by political groups and armed action since 1996 by the Kosovo Liberation Army (or UÇK, acronym for Kosovo). in Albanian from Ushtria Çlirimtare Kombëtare, in Spanish Kosovo Liberation Army, KLA)

The KLA launched a guerrilla war and campaign of terror, characterized by regular shelling and armed attacks on Yugoslav security forces, state officials and civilians known to openly support the national government, including non-KLA supporters. ELK. In March 1998, Yugoslav army units joined Serbian police to fight separatists, using military force. In the months that followed, thousands of Albanian civilians were killed and more than half a million fled their homes, most of whom were Albanians. Many Albanian families were forced to flee their homes at gunpoint as a result of fighting between the national security forces and KLA forces, leading to expulsions by security forces, including associated paramilitary militias. UNHCR estimated that 460,000 people were displaced from March 1998 until the start of the NATO bombing campaign in March 1999.

There was violence against non-Albanians too: UNHCR reported in March 1999 that more than 90 mixed-population villages in Kosovo "have now been emptied of Serb inhabitants" and other Serbs continued to leave, either to be displaced to other parts of Kosovo or to flee to central Serbia. The Yugoslav Red Cross estimated that there were more than 30,000 displaced non-Albanians in need of assistance in Kosovo, the majority of whom were Serbs.

After the breakdown of negotiations between the Serbian and Albanian representatives, under the auspices of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO intervened on March 24, 1999 without authorization from the United Nations. NATO launched a heavy bombing campaign against Yugoslav military targets and then followed up with wide-range bombing (such as bridges in Novi Sad). A full-scale war broke out as the KLA continued to attack Serb forces and Serb and Yugoslav forces continued to fight the KLA, amid a massive displacement of the Kosovo population that was viewed by many international human rights organizations as an act of ethnic cleansing perpetrated by government forces. Several former Yugoslav government officials and military officers, including President Milošević, were later indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia for war crimes. Milošević died in custody before the verdict was announced.

The United Nations estimated that, during the Kosovo War, about 640,000 Albanians fled or were expelled from Kosovo between March 1998 and the end of April 1999. Most of the refugees headed for Albania, the Republic from Macedonia (now North Macedonia) or Montenegro. Government security forces confiscated and destroyed the documents and license plates of many fleeing Albanians in what was widely seen as an attempt to erase the refugees' identities, with the term "identity cleansing" for this action. This made it more difficult to accurately distinguish the identity of those who returned after the war. Serb forces maintain that many Albanians from Macedonia and Albania - some estimates indicate that around 300,000 Albanians have since immigrated to Kosovo as repatriates. Despite the fact that for some the issue is debatable, it is worth underlining the survival of the province's birth, marriage and death records, which are currently in the possession of the Serbian state.

Recent history (from 1999 to present)

The Kosovo War ended on June 10, 1999 with the signing of the Kumanovo Agreement between the Serbian and Yugoslav governments, by which they agreed to transfer the government of the province to the United Nations. A force commanded by NATO (KFOR) entered the province after the end of the war, with the task of providing security for the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo. Before and during the handover of power, an estimated 100,000 Serbs and other non-Albanians, mostly Roma, fled the province for fear of reprisals. In the case of non-Albanians, in particular, the Roma were accused by many Albanians of having helped the Serbs during the war. Following the withdrawal of Serbian security forces, many of them expressed their fear of becoming targets of returning Albanian refugees and KLA members who blamed them for acts of violence during the war. Thousands more were driven out through intimidation, attacks and a crime wave after the war, as KFOR fought to restore order to the province.

Large numbers of refugees from Kosovo still live in temporary camps and shelters in Serbia itself. In 2002, Serbia and Montenegro reported hosting 277,000 internally displaced persons (the vast majority consisting of Kosovo Serbs and Roma), including 201,641 people displaced from Kosovo to Serbia, 29,451 displaced from Kosovo to Montenegro, and around 46,000 internally displaced. from Kosovo itself, including 16,000 refugees who had returned but were unable to inhabit their original homes. Some sources estimate a much lower figure. Thus, the European Stability Initiative estimates the number of displaced at only 65,000, with another 40,000 Serbs remaining in Kosovo, although this would leave a significant proportion of the pre-1999 Serb population unaccounted for. The largest concentration of Serbs in Kosovo is in the north of the province on the Ibar River, but it is presumed that approximately two-thirds of the Serb population in Kosovo still lives in the south of the province, inhabited mostly by the Albanian minority..

On March 17, 2004, serious unrest in Kosovo resulted in 28 deaths and the destruction of some 35 Serb Orthodox churches and monasteries in the province, when Albanians began carrying out pogroms against Serbs. It is estimated that more than 4,000 Serbs left their homes in Kosovo to seek refuge in Serbia itself or in Serb-dominated north Kosovo.

Since the end of the war, Kosovo has been a major source and destination country for the white slave trade, in which women are forced into prostitution or become sex slaves. The growth of the commercial sex industry has been stimulated by NATO forces in Kosovo.

In 2006, international negotiations began to determine the final status of Kosovo, as provided for under United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244 that ended the 1999 Kosovo War. While sovereignty of Serbia over Kosovo was recognized by the international community, a clear majority of the population of the province, made up of the Albanian minority, requests independence.

The UN-backed talks, led by UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari, began in February 2006. While progress has been made on technical issues, the two sides remain diametrically opposed on the status issue itself. himself. In February 2007, Ahtisaari delivered a proposed status agreement to the leaders in Belgrade and Pristina, the draft being based on a UN Security Council Resolution proposing 'supervised independence'; for the province. As of early July 2007, the draft resolution, which is supported by the United States, the United Kingdom and other European members of the Security Council, has been rewritten four times to try to accommodate Russian concerns that such a resolution would undermine the principle of state sovereignty. Russia, which maintained a veto in the Security Council as one of its permanent members, has stated that it will not support any resolution that is not accepted by both Belgrade and Pristina.

The main points of Ahtisaari's document establish the indefinite deployment of international forces to guarantee security, the political guardianship of the European Union through a representative, the power for Kosovo to sign agreements and request entry into international organizations, the formation of a military force of 2,500 men with light weapons, the creation of seven Serbian municipalities with broad autonomy and establishes measures for the protection of the Serbian historical and cultural legacy.

In December 2007, the European Union unilaterally decided to send a "stabilization mission" to the Kosovo region. The union's foreign policy officer, Javier Solana, was entrusted with preparing the transfer of the UN mission in Kosovo to European hands. The mission - without a definite start date - would send 1,400 police officers and 400 other people to Kosovo. The tasks are expected to be completed by the end of January 2008.

The Parliament of Kosovo, meeting in special session on February 17, 2008 in Pristina, declared the independence of Kosovo, unilaterally taking the name Republic of Kosovo for the new one. International reactions have been mixed. Thus, the United States and some countries of the European Union recognized Kosovo as an independent state, but others, such as Russia and Spain, did not. The UN has not yet ruled on the matter.

2010s

On July 25, 2011, Kosovo Albanian police in riot gear attempted to seize several border checkpoints in the Serb-controlled north of Kosovo trying to enforce a ban on Serb imports. This event prompted a large crowd to erect barricades and attack Kosovo police units. An Albanian policeman was killed when his unit was ambushed and another officer was reportedly injured. NATO-led peacekeeping forces moved into the area to defuse the situation, and Kosovo police withdrew. The United States and the European Union criticized the Kosovo government for acting without consulting international organizations. Although tensions between the two sides eased somewhat after the intervention of NATO KFOR forces, the situation remained tense between the two factions.

On April 19, 2013, there was some rapprochement between the two governments when both sides agreed to the Brussels Agreement, an EU-brokered deal that allowed Kosovo's Serb minority to have its own police force and appeals court. The agreement was ratified by the Kosovo assembly on June 28, 2013.

2020s

In April 2021, the Kosovo parliament elected Vjosa Osmani as its new president for a five-year term. She was the seventh president of Kosovo and the second female president in the postwar period. Osmani was backed by Prime Minister Albin Kurti's left-wing Self-Determination Movement (Vetevendosje), which won the February 2021 parliamentary election.

In September 2021, Serbs in northern Kosovo blocked two main highways, protesting a ban on cars with Serbian license plates entering Kosovo without temporary printed registration details. Two Interior Ministry buildings in northern Kosovo, including a car registration office, were attacked. Serbia started military exercises near the border and began flying military aircraft over the border crossing. The NATO mission in Kosovo intensified patrols near border crossings. On 30 September 2021, an agreement was reached between Kosovo and Serbia to end the confrontation. Kosovo agreed to withdraw the special forces from the police. In late July 2022, tensions flared again when the Kosovo government declared that Serb-issued identity cards and vehicle license plates would be invalid, prompting northern Kosovo Serbs to protest again. blocking the roads. The decision by the Kosovo authorities was seen as a reciprocal move as Kosovo documents are rejected in Serbia. In August, EU-mediated talks resulted in an agreement between Serbia and Kosovo whereby Serbia would abolish special document requirements for Kosovo ID holders and the latter would not introduce them for ID holders. of the Serb inhabitants.

Contenido relacionado

114

77

Jackson Day