Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia, which succeeded the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, was a state located on the Balkan Peninsula that existed from October 3, 1929 to December 2, 1945. Composed of the following seven provinces: Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro and Macedonia, Croatia and Slavonia.

The new name of the State was actually common before its official institution, and was little used outside the official sphere. It came from the Serbo-Croatian Jug (south) and Slavija (Slavic territory), a term by which it was designated since the century xix to the South Slavs, although usually not including the Bulgarians.

The existence of the kingdom is politically divided into four distinct phases: the royal dictatorship of Alexander I of Yugoslavia, the regency of his cousin Paul after his assassination, the short government of General Dušan Simović, who overthrew the regent, and the world war, during which the country was dismembered and the kingdom only existed formally. The issue that mainly dominated Yugoslav politics was the form of state and attempts to resolve nationalist conflicts between the country's different communities, especially Croatian discontent over the lack of autonomy from the central government. During the dictatorship and part of the regency, the Government tried to unify the country by force and put an end to regionalism by imposing a unifying Yugoslav nationalism, without success. Only on the eve of the outbreak of the Second World War was a reformist agreement reached between Regent Pablo and the Croatian leader Vladko Maček, which could not be fully implemented and left many dissatisfied.

In international politics, the country maintained its alliances favorable to the winners of the First World War (especially with France), among which it was counted, but, since the mid-1930s, it was strengthening relations, especially economic, with the fascist powers. Very dependent on trade with them and their supplies, when the war broke out it declared its neutrality. It became surrounded by hostile nations allied with Italy and Germany, which increased their pressure on Yugoslavia to join them, which it ended up doing in the absence of allied aid in March 1941, although conditionally. The displeasure on the part of the Army and the population for the alliance with the Italian-Germans led to a coup d'état that ended the regency and precipitated in a few days the invasion of the country, which could not be avoided. The royal government went into exile in Great Britain and the country was divided by the invaders, maintaining its unity only formally and by the refusal of the Allies to recognize the division of the territory by the Axis.

Economically, the kingdom began with a harsh economic depression due to the global agricultural crisis of the late 1920s and the arrival of the Great Depression in Yugoslavia. In the middle of the following decade there was a certain recovery and improvement in the situation in the countryside and in the development of industry, although it was not enough to significantly improve the standard of living of the population, which was growing rapidly. Preparations for war once again worsened the living conditions of the population and the national economy, which was highly dependent on the Axis.

Background

Tensions between Serbian nationalism (emboldened by the centralist character of the State) and Croatian nationalism, accustomed to obstructionist opposition politics, erupted with the assassination in the kingdom's Parliament of the leader of the Croatian Peasant Party by a deputy Montenegrin. The parliamentary system was unable to resolve the country's political problems. The last democratic government, a coalition of four parties chaired by the Slovenian Anton Korošec, presented the resignation of the sovereign in December 1928; Korošec confessed that the coalition members saw no way to end the opposition of the Croatian Peasant Party (PCC). To abandon this, the PCC demanded a federal reorganization of the State. This led the king to close Parliament and take office. governing the country in a dictatorial manner beginning on January 6, 1929. The Vidovdan Constitution was abolished and political parties were banned. However, this only reignited tensions.

In addition to the serious political problem, the dictatorship inherited from the previous period of parliamentary government a growing problem of rural overpopulation, due to the rapid increase in the population and the lack of employment outside of agriculture to absorb it. Of around 14 million of inhabitants in 1931, about 9.2 million lived from agriculture. There were many small landowners who, despite owning land, were not able to survive with their production. About a third of the country's surface was forest., being the timber and derivatives industry the main one in the country and its main export; this breadth of the forests limited the amount of land available for the cultivation of a multiplying population. The amount of territory dedicated to extensive cultivation prevented employment for all farmers, mostly small landowners, and kept their standard of living low.

The royal dictatorship (1929-1934)

Domestic policy

Popular beginning

By royal decree of January 6, 1929, the king abolished the Vidovdan Constitution and all the rights it contained. He also promulgated another law, the defense of the State, which reinforced the anti-communist measures approved in 1921 and prohibited opposition to the new regime. Political parties were dissolved and their newspapers closed, and the formation of new political organizations based on regions, religions or nationality was prohibited. The positions of local administrations were replaced by representatives appointed by the new Government. King Alexander took the powers of the State for himself, appointing a new Government that was only responsible to him, thus ending the period of parliamentary government. The monarch indicated, however, that the dictatorship It would be temporary and had only been implemented due to the country's crisis. The proclamation of the dictatorship and the abolition of the centralist Constitution was initially received with relief and satisfaction by the population. The prime minister chosen by the monarch was the head of the royal guard, General Petar Živković, close to the king, while the ministers were former veteran politicians from all the main political formations, who entered the Government generally without his support (except Korosec). The king's maneuver was not badly received abroad, where he wanted to end the instability in the country, nor at first by the opposition, which was happy about the abolition of the hated Vidovdan Constitution and the sovereign's promises. to begin a new political process. The first expressions against the royal dictatorship came from some Serbian parties, the democrats and the left-wing agrarians, who tried in vain to cooperate with the Croatian Peasant Party. Among the first measures of the Government real were the implementation of censorship and the creation of a special court dedicated to judging political crimes.

On October 3, 1929, the country was officially renamed Yugoslavia and the territorial organization was changed, creating nine new provinces (the banovinas), which replaced the thirty-two provinces. three administrative units in force since 1924, of French inspiration. The units were based on economic and political reasons - the attempt to annihilate regionalisms. The provincial governors were appointed by royal decree and They responded only to the king. It was then that Vladko Maček, leader of the Croatian Peasant Party, began to oppose the royal dictatorship. The new administrative units (banovinas) did not have, however, autonomy.

On July 4, 1930, the sovereign expressed his intention not to reinstate the old territorial organization and not to allow the old parties to return to politics.

In the first months, the dictatorship carried out measures that were considered necessary and urgent. An Agrarian Bank was created (August 15, 1929, the administration was reorganized, inflated by favoritism, and They unified the laws, measures that Parliament had failed to pass since independence. Military oppression in Macedonia was also partially reduced. Administrative corruption was briefly reduced, although the new ministers continued to place their supporters in government positions.

Decline of the dictatorship

Within a few months, however, its lack of a clear program became evident and the appearance of the Great Depression accentuated the regime's difficulties. The worsening of the economic crisis, which had already begun in agriculture In 1927, with the continuous reduction in the prices of its products, it impoverished the majority of the population, peasants. The drop in the prices of the main Yugoslav exports (agricultural products and raw materials) harmed the balance of payments. The growing protectionism of the industrialized countries - the destination of their exports - in the new decade undermined the country's foreign trade. The economic situation began to deteriorate noticeably in 1931, with the impossibility of emigrating and the continuous withdrawal of short-term credits. to the country, which had begun the previous year.

On September 3, 1931, in part to facilitate obtaining international credit to alleviate economic hardship, the regime promulgated a new Constitution. The regime also tried with this measure to gain popularity and try to prevent an overthrow of the regime like what happened at that time in Spain, which had ended the monarchy. Despite guaranteeing individual rights, it contained severe political limitations: it granted great power to the Government and the king, parliamentary elections They were no longer carried out by secret ballot and half of the Senate was chosen by the monarch. The cabinet remained responsible only to the king, who could change it at will. Article 116 granted it extraordinary powers in emergency situations.

The king had achieved the temporary destruction of the old political parties, none of them national, but he had been unable to replace them with other political formations, forming a vacuum in Yugoslav politics in which the monarch governed based primarily on the Army and the bureaucracy. In particular, the dictatorship had disrupted the Serbian parties, while inadvertently strengthening the main Croat, Slovenian and Bosnian parties. Meanwhile, despite reformist proclamations, the centralizing policies that had displeased the Serbians were maintained. the regionalists. The opposition, however, had serious disagreements: the Croatian Peasant Party wanted to give priority to the territorial reform of the State to implement a federal system that recognized Croatian political rights, while the Serbian formations generally preferred to start with restore parliamentary democracy.

The State had become a police State, with zero independence of the judiciary with respect to the dictatorship and an abundance of political trials against the opposition (Croatian and Macedonian nationalists or communists). A regime of political terror and repression. There was no freedom of the press or expression. In the autumn of 1930, he lost the support of the Slovenian Anton Korošec, further revealing the true Serbian centralist character of the regime. Discontent with The royal government was broad, both politically (lack of agreements with Croatian nationalism, loss of political freedoms) and economically (economic crisis).

Despite the promulgation of the new Constitution of 1931, freedoms were suppressed and the new Lower House and Senate were elected by the regime, without a secret vote. The electoral law promulgated shortly after the The Constitution also established a new way of distributing the seats: the party with the majority obtained two-thirds of them plus the part proportional to its votes of the other third, thus ensuring a comfortable majority for the winner of the elections, avoiding the previous need for coalitions. The law allowed the formation of political parties, but prohibited them from opposing the political and social order of the State, from being confessional, from defending a certain region or culture, or from being contrary to Yugoslav unity. The opposition, considering that the Government's maneuver was a farce, decided not to participate in the Parliament elections, which were held in November 1931 with the only participation of the government list, headed by Živković. In December, to try to To increase support for the regime, a political formation was created to serve as a base, the Yugoslav National Party, in which right-wing radicals, dissidents from almost all the old parties and opportunists were mainly concentrated. Although the political reform and the The elections had not served to legitimize the regime, the opposition remained divided, mainly due to Maček's Croatian nationalist ambitions, which the rest of the parties opposed to the royal dictatorship rejected.

Even the Parliament elected by the regime ended up opposing his actions and the king tried to reconcile with the political opposition as early as 1932. Contacts with Croatian leaders did not bear fruit, as they were convinced that the king's weakness would allow them achieve their political objectives without agreeing. General Živković was relieved in April 1932 at the head of the Government by Vojislav Marinković, a distinguished politician and former Minister of Foreign Affairs, who was to give a more cosmopolitan image to the regime and make it less military. He formed a new party, the Radical Peasant Democratic Party, to support the regime but, sick and politically isolated, too reformist even for the king, he was replaced on July 2, 1932 by Milan Srškić, former Radical, minister. of the Interior of the unemployed and contrary to the promises of political liberalization made by him. Eminence of the previous cabinets of the dictatorship in which he had held various ministerial positions, he had earned numerous enemies among the opponents for his measures. His The government lasted a year and a half and accentuated the tension with the opposition and the repression. The opposition, seeing the prestige of the Government decline, presented two reform manifestos in the winter of 1932-1933. Abroad, the Ustashas They increased agitation against the regime and its defense of Croatian independence, committed terrorist attacks and tried in vain to trigger a revolt in the country in September, which was harshly repressed.

The Government responded by slightly moderating the electoral requirements but, at the same time, deciding to try prominent opposition leaders, such as Maček or Korošec, a measure that even the Serbian opposition condemned. During 1933 the situation continued to worsen, The Government refusing to legalize the Radicals and the Social Democrats.

The growing economic hardship of the peasantry led to the approval of various measures in 1932: in April the moratorium on the payments of their debts and their reduction was decided. In the summer the banking crisis eliminated credit and the imposition of a Strict control of foreign trade almost put an end to it, also cutting off the scarce credit coming from abroad. Agricultural prices reached a minimum in 1933-1934 and the following year the Government had to devalue the currency by a third.

On January 27, 1934, Srškić was relieved by the veteran Radical Nikola Uzunović, president of the government party and symbol of the exhaustion of the royal government. The change of prime minister signaled the king's intention to try to reconcile with part of the opposition to the dictatorship in the face of its growing isolation, the economic crisis, the lack of progress on political problems, and the deterioration of the international situation.

There were basically two opposition groups in exile, Croatians and Macedonians. The former were divided into three main groups: the followers of Stjepan Radić, the reactionary conservatives in favor of the restoration of the Habsburgs, and the terrorists and ultranationalists of the new Ustasha formation of Ante Pavelić. The latter had the support of Hungary and Italy, revisionists. The Macedonians were divided between the ORIM terrorists and the autonomists.

Faced with internal failure and external threats, the sovereign began the dismantling of the royal dictatorship at the end of the summer of 1934. In January he had already replaced the tough Srškić with the more moderate veteran Uzunović, and in September, before of his visit to Bulgaria and France, he promised Maček his early release and the beginning of negotiations. On October 9, 1934, the process was temporarily halted when a Macedonian guerrilla hired by the Croatian nationalist Ustasha assassinated King Alexander and the minister of French Foreign Affairs in Marseille. By then the royal dictatorship, repressive and bloody, was a palpable failure that had not resolved the problems that had arisen (political, economic and social) in 1929. The The death of the king, however, did not produce the disintegration that its authors hoped to achieve, uniting the country temporarily in the face of the external threat. The monarch had managed, however, to reinforce the position of the Croatian nationalists, while he had destroyed the formations Serbian policies.

Foreign policy

During Alexander's reign, the preference for the alliance with France and the Little Entente was maintained.

Starting in 1933, with the arrival of Hitler's Government and even more so in 1934, with the civil war in Austria in February, the signing of the Rome Protocols by hostile neighbors and the attempted forced annexation of Austria in July With the assassination of Chancellor Dollfuss, Yugoslavia saw the international situation worsen.

At the end of his reign, Alexander managed to begin a rapprochement with neighboring Bulgaria, with which he maintained a tough rivalry for the possession of Macedonia. This improvement in relations produced the elimination of armed bands that, based on Bulgaria, attacked Yugoslav territory and had had great influence on Bulgarian politics. In February 1934 the country had also joined the Balkan Entente, an organization that brought together almost all the countries in the region with the aim of increasing the cooperation between them, but that excluded Bulgaria, which refused to renounce its territorial claims, and Albania.

The trip in which the king was assassinated in October 1934 was part of his effort to achieve a network of regional alliances favorable to France that would form a counterweight to the one Mussolini was also forming in the region. Minister Barthou, assassinated alongside the monarch in Marseille, had visited Belgrade in June and the royal trip was the result of this and had as its objective the continuation of the Franco-Yugoslav talks.

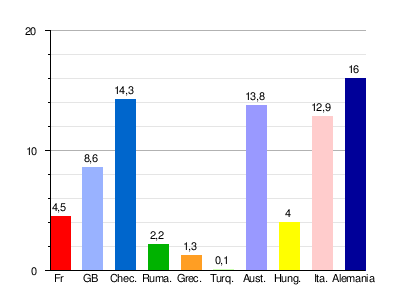

Foreign trade did not favor the Yugoslav policy of alliances, being much greater with its theoretical enemies than with its allies. The country's main exports, which declined enormously during the Great Depression (from eight billion dinars to three between 1928 and 1933), consisted mainly of wood, agricultural and livestock products, and minerals. Faced with the substantially stable position of the rest of the products as a proportion of Yugoslav exports, the sale of minerals increased notably throughout the decade as a consequence of the preparation for war by importers, mainly Germany. Italy's importance, great at the beginning of the period, declined rapidly after the country's participation in the sanctions approved by the League of Nations for the Italian attack on Ethiopia.

The Government also opposed the participation of volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, threatening to withdraw Yugoslav citizenship from anyone who took part, prohibiting recruitment or issuing visas to Spain (March 1937). However, one thousand seven hundred Yugoslav brigade members took part in favor of the Second Spanish Republic, and at the end of the conflict the survivors were not allowed to return, and they had to do so illegally. Several hundred volunteers were interned in France after the war for the loss of nationality approved by the Stojadinovic Government. Surviving veterans of the Spanish War formed the core of the partisan movement during the World War. Concerned about the possible destabilizing effect of Spanish conflict in Yugoslavia, the Government tried to ignore it, censor information about the conflict and adopt a position of neutrality, increasingly favorable to the Franco side.

The regency (1934-1941)

Domestic policy

Alexander was succeeded on the throne by his son Pedro II, but since he was a minor, his uncle Prince Paul assumed the regency along with two other regents of lesser weight.

|

The dictatorship had clearly failed in its attempt to end the Croatian resistance to the State, reinforcing this position while destroying the Serbian political structures, weakening its parties. The regime, despite its ruin, is He refused to make substantial changes in the laws of the country hiding in the minority of the king. This further reinforced extremists, both Croats and Serbs. The prince maintained a position contrary to political and economic and economic reform, but he was willing to try to reach an agreement with the HSS.

After an attempt by Prime Minister Nikola Uzunović to form a cabinet only with his Serbian supporters, frustrated by the regent, he resigned (December 20, 1934). The regency commissioned the government for the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Confidence man of King Alejandro, Bogoljub Jevtić.

Jevtić began his government with moderate measures, included non -serbian ministers in the cabinet, promised free elections and released the main leader of the opposition, the leader of the Croatian peasant party, Vladko Maček. He also declared his intention to take to carried out a progressive decentralization of the administration. In the May 1935 elections, he presented candidates in all constituencies, despite his formation he only had a real support in the old Serbian territories, achieving a majority of votes and seats thanks to the electoral law, despite The complaints of the opposition, which denounced the elections for amañados. The opposition had presented together with Maček as a candidate. The elections were actually a moral victory of the opposition, managing to defeat several ministers of the cabinet and beating in certain important districts despite government intimidation.

The opposition refused to go to Parliament and, when in this one a campaign of hard attacks on Maček began the regent Pablo achieved the fall of the Jevtić cabinet favoring the resignation of the Minister of Defense, General Petar Živković, of the non -Serbian ministers and the prestigious Minister of Finance, Milan Stojadinović. The regent wanted New elections, but preferred instead of appointing a new government.

The Stojadinović government

Maček was then willing to allow a government headed by Stojadinović, Minister of Finance of the previous government, and to participate in the Parliament if the electoral law was changed and the freedom was guaranteed in the voting. The new government of Stojadinović (June 24, 1935 included the main Slovenian politic of the politicians identified with the dictatorship, replacing them with technocrats or politicians outside the Alejandro regime. The government began by relaxing censorship, amnestying thousands of political prisoners, moderated terror and allowed the installation of a Statue of the murdered Stjepan Radić in Zagreb.

In less than two months, Stojadinović Remoked the government party creating the Yugoslava Radical Union (JRZ), amalgam of radicals, Slovenian populists and JMO. The formation should serve as a foundation of the power of the prime minister, which In December 1935 he got rid of the former radical leaders of the JRZ who believed to be able to manipulate him. On March 6, 1936 he came out unharmed and reinforced by an attempt at murder in Parliament. The ancient positions of the dictatorship then formed An opposition coalition that did not weaken Stojadinović, but gave him an aura of renewal in front of this. The main opposition block with Maček at the head continued without going to the Courts, facilitating the prime minister's plans. The various attempts for Arriving an agreement on the Croatian problem did not bear fruit.

After consolidating in the government, Stojadinović began to make reforms, relieving the serious problem of the debts of the peasants in September 1936. The support of the farmers such as the implementation of agrarian insurance, construction of silos and other public works, creation of agricultural research institutes, etc. This policy, the good crops of those years and the German disposition to absorb much of the Yugoslava agricultural production gave great prestige to the prime minister among the peasants. Agricultural development was not enough to end the problem of rural overpopulation. During its government the industrialization of the country was also supported and mining began to develop. The balance of payments began to be positive and The national budget had surplus.

At the end of 1936, the opposition to the regime seemed to have the overwhelming majority of the ancient Austro -Hungarian subjects. The prime minister had achieved a victory in the municipal elections of December 1936, but the Croatian districts still supported the opposition to the opposition. Despite the government's opening promises, there were no changes in the electoral census and the state terror was maintained in Macedonia. For the Croatian nationalists, their political program still had precedence to the social one. The first contacts between Stojadinović and Maček in 1935 had failed.

At the beginning of 1937, he tried to re -reach an agreement with Maček but this, untouched in the recent elections, maintained his demands. Stojadinović then tried to undermine the basis of his adversary with the measures in favor of the peasants and An attempt to concordat with the Holy See, believing that the sympathies of Agro Croatian, Catholic. East, which had been signed on July 25, 1935, had not been ratified by the hostility of the Orthodox Church would be signed Serbia. His attempt to approve the law in 1937 won the enmity of this while Croatian voters, more interested in their political demands than in religion, did not support him.

The Concordat, which was ratified by the Lower House, but did not become by the Senate, was a political error of the prime minister, who was forced to repeal him in 1938, after the disinterest in Croatian and the hostility of the Serbian Church.

In the autumn of 1937, the prime minister reorganized his training to control it better and began to adopt fascist paraphernalia, trying to give his government the support of a mass movement, without excessive success. On October 8 From 1937 the moderate opposition, formed by the Croatian peasants and several Serbian parties, signed a cooperation agreement against the regime, which was well received by the population. The opposition gathered demanded a new electoral law, new free elections and the formation of a constituent assembly that drafted a new constitution with general approval.

|

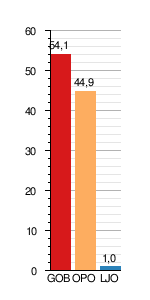

With the peasantry happy with their ability to sell their products in Germany and obtain affordable industrial products from it and the apparent diplomatic victories that should have isolated Maček, the prime minister brought forward the elections to December 1938, sure of his triumph. Despite being held without a secret vote, the elections meant a defeat for the prime minister, who only obtained 54.1% of the votes compared to 44.9% for the opposition. The distribution of the vote also reflected the political division that it had failed to eliminate: while the Government had obtained 70% of the votes in the former Serbia, the opposition had obtained 80% of the votes in the territories with Croatian populations. The Croatian members and Slovenians withdrew from the cabinet, weakening the prime minister.

On the eve of the opening of parliament, January 15, 1939, Maček's deputies met in Zagreb, without intending to go to Belgrade, and proclaimed their indifference towards the Yugoslav parliament, indirectly threatening civil war. Faced with the deterioration of the international situation and that of the opposition, despite his recent moral victory in the elections, the regent Pablo began secret talks with Maček. When he showed his displeasure with the prime minister, the regent dismissed him on February 6, 1939, placing the malleable Dragiša Cvetković in his place, willing to follow Pablo's guidelines.

The Regent's Government

At the beginning of the spring of 1939 and with the new international crisis due to the disappearance of Czechoslovakia in March, Maček and Cvetković maintained contacts to try to achieve a political agreement. Maček at the same time continued his alliance with the opposition Serbia in order to achieve the establishment of a democratic regime and secret contacts with Mussolini regarding possible Italian support for the independence of the Croatian territories. Maček wanted to obtain clear concessions from the regime while the regent considered the agreement with the Croatian leader needed by the growing international tension that could lead to war at any moment and believed that it would free the regime from its need to liberalize and weaken the most radical opponents such as the Ustashas.

After lengthy negotiations, the agreement (known as Sporazum) was only reached on August 20, 1939, days before the outbreak of World War II, and was announced six days later. The pact involved the creation of a new Croatian administrative unit with autonomy, its own Parliament and a governor appointed by the throne and responsible to it and the autonomous Government, but not to the central one, leaving the new province (which had 27% of the territory and 29% of the country's population) united to the rest of the nation through the monarch.

A new cabinet was formed with several opposition ministers. On August 26, 1939, Maček became deputy prime minister of the Government and four of his co-religionists took ministerial portfolios. The two legislative chambers were dissolved, the promulgation of a new electoral law was announced that was to precede the planned elections and the Government was given power to administer the country through decrees until the new Cortes were elected. The agreement did not achieve, however, its objective of put an end to the nationalist problem in the country: the Bosnians, Serbs and Slovenes wanted to obtain the same autonomy recently granted to the Croats, the Serbs of Croatia felt helpless in the face of the new autonomy and the extremist Croatian nationalists, increasingly More numerous, they thought that the concessions obtained were insufficient. Maček had also destroyed the unity of the opposition in his negotiations with the Government, since his Serbian allies had opposed them and accused the Croatian leader of betraying the democratic cause.

Foreign policy

The assassination of the king in October 1934, which had the complicity of Hungary and Italy and occurred due to the incompetent surveillance of the French police, greatly increased tension with these countries. France and Great Britain, interested in win Mussolini's support against Hitler, they did not, however, allow Italy to be blamed for the deaths during the investigation and at the League of Nations. Disillusioned by the role of France, Yugoslavia's main traditional ally, it was approaching Nazi Germany, with which he had no conflicts, and temporarily improved the relationship with Italy, managing to neutralize fascist support for the Ustasha terrorists between 1937 and 1941. In September 1936, after having participated in vain and with great economic damage in the economic embargo on Italy, the two countries signed an economic agreement.

The formation of a new coalition government with Stojadinović at the head meant a departure from the traditional pro-French orientation of Yugoslav foreign policy. There was gradually a rapprochement with the fascist powers. Two reasons that facilitated the new rapprochement with These were the German willingness to buy Yugoslav agricultural production at a time when external markets had disappeared for it, and the fact that the prime minister had them as ideological and organizational models. In this he had the support of the conservative Slovenian minister Anton Korošec. France and the United Kingdom, on the other hand, showed no interest in increasing trade with Yugoslavia, which lacked the foreign currency to buy their products. Traditional Italian hostility gave way to greater closeness, which was reflected in the treaty of friendship between the two nations signed in March 1937. This also eliminated previous Italian support for the Croatian Ustasha ultranationalists.

|

|

|

|

|

|

French-British passivity in the face of the remilitarization of the Rhineland in March 1936 further convinced Stojadinović of the need to win the favor of Germany, whose power was growing. Two weeks after the crisis, he granted Krupp the modernization of the Zenica blast furnaces, discarding the French and Czechoslovak competitors, theoretical allies. The succession of economic agreements with Germany produced Yugoslav economic dependence on the Reich already in mid-1938. Stojadinović exchanged diplomatic dependence on France for economic dependence on Germany Subsequent attempts by France and Great Britain to balance German influence failed due to lack of momentum and disinterest, and Italy did not have the economic potential to overshadow Germany.

The prime minister managed to improve relations with the fascist powers, with the hostile Bulgaria and Hungary, without breaking with France and Great Britain or abandoning the Balkan Entente. He allowed without any problem the annexation of Austria by Germany in March 1938 and September did not come to the aid of its theoretical ally, Czechoslovakia, against German threats.

After the relief of Stojadinović in February 1939, Italy rushed to occupy Albania on April 7, 1939, as it had agreed with him, and Germany was content with the inclusion of the former ambassador in Berlin as Minister of Foreign Affairs. Foreign Affairs of the new Government under the control of Regent Pablo. In March the disappearance of Czechoslovakia cost Yugoslavia the loss of the main source of weapons and the transfer of Czechoslovak investments to Germany. Mussolini also established contact with the Croatian peasants with the intention to destabilize the Government. Italo-Yugoslav relations worsened again. At the beginning, however, Germany and Italy decided not to support the attempts to dismember the country, as long as it maintained its recent proximity to the Axis. The Yugoslavs They were quick to ensure their future neutrality and not to enter any coalition against Italians and Germans. Despite German attempts at intimidation, the regent refused to leave the League of Nations or the Balkan Entente. In May the country He secretly sent his gold reserves to the United Kingdom, which were then moved to the headquarters of the US Federal Reserve in New York.

Yugoslavia's situation in Europe gradually deteriorated. After the outbreak of World War II, Yugoslavia immediately declared its neutrality. The belligerents approved the Yugoslav position: Germany wanted to maintain the supply of Yugoslav raw materials and The Allies were not in a position to demand more from the Belgrade Government. Italy, however, was more bellicose. In January 1940 Mussolini approved a meeting with Pavelic again. In June 1940, Yugoslavia's main ally capitulated., France, after Belgium and the Netherlands had done so shortly before. In the summer Hitler prohibited the Italian attack on Yugoslavia, for which Mussolini had ordered a campaign plan to be prepared. In the autumn, the neighboring nations fell under German rule, signing one after another the Tripartite Pact (Romania on November 23, 1940, Hungary on November 20, 1940 and Bulgaria on March 1, 1941). The Italian attack on Greece in October 1940, which ended with The temporary Italian defeat and the need for German aid to its ally further complicated the situation in neutral Yugoslavia. Hitler wanted to ensure cooperation or clear Yugoslav neutrality for his planned offensive against Greece.

Despite the traditional hostile attitude of the Yugoslav royal family to the Soviet regime, the deterioration of the international situation and the need for a counterweight to the growing German dominance made it advisable to review the situation. In March 1940, talks began with the Soviet Union, which led to the signing of a trade treaty on May 13, 1940 and the establishment of diplomatic relations in June. A subsequent Soviet offer of arms in November failed to come to fruition.

Surrounded and economically dependent on Germany, Yugoslavia found itself increasingly pressured by Hitler to sign the Tripartite Pact, alternately through veiled threats and various offers. The insistence became more acute after December 1940, but Yugoslavia resisted. pressures for several months at the beginning of 1941. With its usual arms supplier (the Czechoslovak Škoda factory) in German hands, with no alternative to supply weapons, with its own industry insufficient to do so and poor communications, the Yugoslav Army He found himself in a desperate situation in the face of German threats. His deployment was also inadequate: he was stationed along the borders for political reasons.

Faced with this situation, on March 25, 1941, the Regent's Government signed the Pact in Vienna, with the reservations obtained from the Germans: the commitment not to station troops and not to use Yugoslav territory for the campaign against Greece..

Prelude to war

Domestic policy

Serbian discontent with what was considered a capitulation resulted in the coup d'état of March 27, 1941, organized mainly by certain air force officers. General Dušan Simović, head of the air forces, formed a new Government. While the crowd celebrated the coup in the streets of Belgrade, in Ljubljana and Zagreb this action did not arouse enthusiasm and was interpreted as Serbia's unilateral decision to enter the war. The regent went into exile and proclaimed himself the coming of age of King Pedro II.

Despite the impression on the street and abroad, Simović desperately tried to calm the Germans, declaring his intention to uphold the country's commitments, including the newly signed Pact, and appointing a theoretical foreign minister. pro-German.

Foreign policy

Hitler rejected the new Government's attempts at reconciliation, ordering the Army's immediate invasion of the country a few hours after the coup, which began on April 6, 1941 with a brutal bombing of Belgrade. The day Previously, the Yugoslav Government, trying to strengthen its position, signed an agreement of friendship and non-aggression with the Soviet Union, which ultimately did not bring it any aid.

On April 10, 1941, the Ustasha proclaimed the independence of the new Independent State of Croatia. On the 12th Belgrade fell. On the 17th the remains of the Army and the Government surrendered and the king went into exile; They settled first in Athens, then in Jerusalem and finally in London.

Social and economic evolution

|

|

The problem of agriculture

Despite the agrarian reform applied after the First World War, the fate of the peasantry, the main social class of the country, did not improve. The rapid increase in population, the disinterest of the Government, the difference in Prices between agricultural products, which were cheaper, and industrial products, which were more expensive, the lack of credit and excessive taxes were the main causes of the hardships of the peasants. Emigration became impossible as a solution to poverty due to the impediments established. by the traditionally receiving countries and was limited to a balance of 57,237 people between 1930 and 1938. Industrial growth was so meagre that it could only absorb a small percentage of the growing population; Consequently, agricultural overpopulation increased. It is estimated that in 1931, 61.5% of the peasantry was unnecessary for the low Yugoslav productivity. The inability of peasants to save hampered industrial and commercial development, since the lack of savings limited credit. The absence of savings also did not allow investment in the improvements necessary to increase the productivity of the land. The smallness of most farms did not favor mechanization, which was very expensive. Most peasant households, except In the north of the country, they were limited to a subsistence economy with primitive production methods. The peasant diet, poor and centered on cereals and potatoes, facilitated the production of agricultural surpluses for export, not because of large production, but due to low internal consumption. Productivity was low.

For its part, the Government did not show much interest in agriculture: if in 1929 the budget of the Ministry of Agriculture was 1.06% of the total, in 1931 it had been reduced to 0.76%. It also did not apply the measures. necessary to ensure credit to the majority of farmers due to the lack of collateral. In 1932, 35.7% of rural households were in debt and a large part of the rest needed credit, which they did not obtain. The previous year it was calculated that the peasants' debt reached more than 80% of their income that year. 45% of those debts were in the hands of usurers.

The distribution of the tax burden, with 76.3% in indirect taxes in 1931-1932, significantly harmed the peasants. It is estimated that more than 40% of the meager peasant income was dedicated to paying taxes. The use of the taxes collected did not satisfy the farmers either, who felt that they did not benefit their well-being: the distribution of the budget in effect favored the ministries of Defense and Interior, to the detriment of those of Health or Agriculture, for example. The tariff policy benefited the most industrialized areas, but harmed the fundamentally rural areas.

State measures to improve production or reduce debt were insufficient to stop the impoverishment of the rural population. 67.8% of the peasantry lacked the land necessary to subsist (a minimum of five hectares) in 1931. Yugoslavia suffered from a shortage of arable land for its large rural population.

The living conditions of the population, in general, were poor, which worsened with the arrival of the Great Depression. Widespread malnutrition also led to an abundance of diseases, which was also helped by health problems. housing and lack of hygiene. Housing in general was of poor quality. In the Zagreb region, not one of the poorest in the country, 73.2% of peasant households had a single room for all activities of the family; In 63.4% of households, five or more members had to sleep in the same room, and 48.7% did not have latrines. The poorest city dwellers, who made up the majority of the urban population, lived in equal or worse conditions. Hygienic conditions, both due to tradition and, mainly, due to poverty, were deficient, and caused the country to suffer a high rate of diseases: it was the highest in Europe for tuberculosis (19.9 percent). 10,000), affecting nearly half a million people out of a population of fifteen million. Malaria affected more than 4% of the population and syphilis was also widespread. Public attempts to improve health of the very poor population were meager.

Social development

The State made great efforts to reduce the illiteracy of the population, with a very irregular distribution according to the regions (lower in the north and higher in the south), notably increasing the number of primary schools and teachers. Even so, the The illiteracy rate barely reduced from 51.5% in 1921 to 40% in 1940. The primary education system was under the direct control of the central government and was not exempt from corruption and favoritism on the part of the ministers of the time. Relative independence of the universities, on the contrary, together with the perception of injustice and inequality among the many students of humble origins, led to the formation of numerous radicals among them, who lacked political power during the monarchical period.

In the two decades that elapsed between the world wars, a series of labor and social security laws were enacted that were, however, insufficient.

Attempts at industrialization

As an alternative to agrarian development, the State tried to promote industrialization. On the eve of the world war, railways, telegraphs, telephones, radios, most banks, the river merchant fleet, and commercial ports and some mines, sawmills and other industries were state property. To promote the industry, the Government applied high import tariffs and tried to attract foreign credit. The tariff policy favored the industry, although to the detriment of agriculture.. Most of the industrial investments of the period were financed with credit from abroad. In the interwar period, the difference between the most industrialized regions (the north and northeast of the country) and those that were less industrialized grew: the strength of The industry was greater where it already existed before the creation of the kingdom, sharpening the differences.

Despite the expansion of industry, especially that related to the transformation of agricultural products and textiles, growth was insufficient to absorb the rapid increase in population. Between 1918 and 1939 the population increased by four million, while the number of industrial workers only reached 385,000 people. The factories at the end of the period were also not able to sell everything they could produce, both due to the low national purchasing power and the protectionist measures of neighboring countries.. Mining, more important than in other countries in the region due to the country's wealth in various deposits, did not employ a significant percentage of the population either. The ownership of the mines was, furthermore, in foreign hands.

Trade

Given the preeminence of agriculture in Yugoslavia, most of its exports were of rural products. Most international trade was concentrated, also in potentially hostile and revisionist countries. In 1930, 57.7% of its Foreign trade was carried out with Italy, Austria and Germany. The global depression also drastically reduced commercial exchanges: in 1932 these only represented 38.7% of the value of those carried out in 1929.

The prices of agricultural products, the basis of income for the majority of the population, also sank. The reduction in the import of raw materials and agricultural products from Central and Western Europe allowed Germany to gain commercial hegemony in the region thanks to its willingness to absorb a large part of the exports and pay prices higher than those of the free market. Since 1933 the balance of payments with Germany became increasingly positive for Yugoslavia, but at the same time the economic dependence of the country, as well as that of its neighbors on the Reich. Attempts to reduce dependence failed and in fact it increased after the reduction of trade with Italy during the application of economic sanctions between November 1935 and September 1936. From 1936 onwards, Germany became the first trading partner, with increasing importance. In 1939, after the annexation of Austria in 1938 and the Czech part of Czechoslovakia in 1939, Germany controlled more than 50% of imports and Yugoslav exports. In October 1939, it had to grant trade concessions to the Axis and reduce national consumption to meet established quotas. With the defeat of Belgium, Holland and France in the spring of 1940, the country It came under German economic domination even before the invasion of April 1941.

Balance of the period

The dictatorship of King Alexander did not achieve its objectives of ending the problems of regionalist nationalisms nor the precarious economic situation of a large part of the population. The subsequent regency of his cousin Pablo did not succeed either. Despite the last-minute agreement with Maček's Croatian opposition, the rest of the communities remained dissatisfied and the most extreme among the Croats themselves were not satisfied with the pact.

Despite the amount of raw materials available in the country, a powerful industry was not developed and what existed depended largely on foreign capital and experts. Investment facilities for foreign capital attracted certain investments, but They turned the national economy into a semi-colonial one. Despite state attempts, especially at the end of the 1930s, to boost industry, its growth was not enough to absorb population growth or alleviate rural poverty, nor to ensure stable economic growth for the country. Agriculture, which employed 79% of the population in 1921, continued to employ 75% of it in 1938. Successive governments also did not devote the necessary attention to agriculture, contenting themselves with an agrarian reform after the First World War that failed to improve the lot of the peasants. When the Great Depression arrived, a large percentage of the peasants who obtained credit, usually at usurious interest, accumulated large debts that the different governments They tried in vain to reduce. Access to credit for the peasantry was not solved.

When the war came, the population was disillusioned, Croatian recruits tried to avoid going to the front, deserted or refused to fight, while the Serbs were not even a shadow of the Army of the First World War. The regime had earned the rejection of all communities and the opposition, opportunistic and frivolous, had not maintained a constructive stance either. Despite dedicating nearly 50% of the state budget to the Army at the expense of improvements in the countryside, the forces armed forces were unable to resist the onslaught of the Axis.

Contenido relacionado

821

379

139