Kilimanjaro

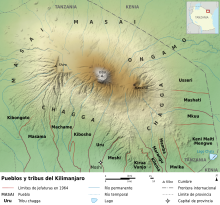

The Kilimanjaro is a mountain located in the northeast of Tanzania, formed by three inactive volcanoes: the Shira, in the west, of 3962 m altitude; the Mawenzi, in the east, of 5149 m and the Kibo, between them, the most recent from the geological point of view and whose peak, the Uhuru, is rises to 5891.8 m. It is the highest mountain in Africa, the highest free-standing mountain in the world—some 4900 m high from its base on the plateau—and the fourth ultra-prominent peak in Earth. It is also known for the famous ice fields on its summit, which have been shrinking dramatically since the early XX century and it is estimated that they will disappear completely between 2020 and 2050. The decrease in snowfall responsible for this decline is often attributed to global warming, in addition to a significant process of deforestation. Despite the creation of the Kilimanjaro National Park in 1973, although this park plays an essential role in the bioclimatic regulation of the hydrological cycle, the forest belt continues to narrow, due to the fact that the mountain is home to Maasai herders in the north and in the west, who need high altitude meadows to graze their herds, and Chagga peasants to the south and east, who cultivate increasingly large plots in the foothills, despite a process of awareness that began at the beginning of the century XXI.

After the surprise caused in the scientific world by its contemporary discovery in 1848 by Johannes Rebmann, Kilimanjaro aroused the interest of explorers such as Hans Meyer and Ludwig Purtscheller, who reached the summit in 1889 accompanied by their guide Yohanas Kinyala Lauwo. Later it became a land of evangelization that was disputed by Catholics and Protestants. Finally, after several years of German and later British colonization, it saw the emergence of a Chagga elite that became the basis for the birth of a national identity and the independence of Tanganyika in 1961.

Subsequently, it became an emblematic mountain, evoked and represented in art and symbolized in numerous commercial products. It is highly appreciated by the thousands of mountaineers who make its ascent taking advantage of the great diversity of its fauna and flora.

Toponymy and etymology

The name used to designate the mountain as a whole is spelled “Kilimanjaro” in Spanish and English, and “Kilimanjaro” in French. It is also called, in maa, Ol Doinyo Oibor, which means "white mountain" or "bright mountain". Its name was adopted in 1860 and would come from the Swahili Kilima Njaro. The name Kilimanjaro was already the subject of early toponymic studies, and the German explorer and linguist Johann Ludwig Krapf saw it as the "mountain of splendor", without further explanation. In 1884, Gustav Adolf Fischer, also a German explorer and naturalist, claimed that injaro was a demon of the cold, an idea shared by the geographer Hans Meyer during his ascension in 1889, but the term injaro only it is known by the inhabitants of the coast and not by those who live in the interior, who also did not believe in anything but beneficent spirits. The explorer Joseph Thomson was the first to suppose, in 1885, that it meant "shining mountain". If the diminutive kilima means hill, hill or small mountain, this theory would not explain why the word >mlima is not used to designate the mountain in a less inappropriate way, except for emotional reasons or deformation. Njaro refers to whiteness, reflection in Swahili. On the other hand, in the Maa language, ngaro or ngare designates water or the sources. But jaro can also designate, in kichagga, a caravan, and an alternative theory proposes as origin the terms kilmanare/kilemanjaare, kilelemanjaare or even kileajao/kilemanyaro, whose meaning is respectively "that defeats the bird" or "the leopard" or "the caravan". However, this name would not have been imported until the middle of the XIX century by the Chagga, who only used to name each of them separately. peaks they knew of, so this explanation would be anachronistic.

Kilimanjaro is made up of three main summits or peaks, which are the Shira, the Mawenzi (in kichagga, Kimawenze or Mavenge, which means "divided summit", whose appearance would be the subject of a local legend) and Kibo (in kichagga, Kipoo or Kiboo, which means "stained", because of a dark rock that protrudes between the perpetual snows, also called Kyamwi, "the bright one"). In the latter is the culminating point of the group, the Uhuru peak (in Swahili, "freedom"). It had previously been named Kaiser-Wilhelm-Spitze, from 1889 to 1918, in honor of Wilhelm II of Germany following the colonization of German East Africa after the signing of several treaties between Carl Peters and the local leaders, until the handover of Tanganyika under UK administration.

Geography

Situation

| Topographic maps of Tanzania (on the left) and the Kilimanjaro and Mount Meru (on the right). | |

Kilimanjaro rises in northeastern Tanzania to 5891.8 m altitude according to measurements made in 2008 by GPS positioning and gravimetry, and replacing the 5895 m obtained in 1952 by a British team. Its altitude, which has been the subject of various measurements since 1889 (with results varying by up to 100 metres), They make it the highest point in Africa, which is why it is part of the so-called "Seven Summits". It is located near the border of Tanzania with Kenya that passes at the foot of the northern and eastern slopes of the mountain. It stands alone from the surrounding savannah, jutting out with a drop of 4,800 to 5,200 m, also making it the highest isolated mountain in the world. It covers an area of 388,500 ha.

The mountain is an oval-shaped volcanic complex 70 km from northwest to southeast, by 50 km from northeast to southwest, and lies 340 km south of the equator. Mount Meru lies 75 km to the southwest and Mount Kenya, Africa's second highest peak, to 300 km to the north. The nearest city, Moshi, is located in Tanzania, to the south of the mountain and constitutes the main starting point for its ascent. In service since 1971, the Kilimanjaro International Airport, which is located fifty kilometers southwest of the summit, connects the entire region and its parks. Dodoma, the capital, and Dar es Salaam lie 380 km to the southwest and 450 km to the southeast respectively, while Nairobi in Kenya is 200 km to the north-northwest. The Indian Ocean coast lies at a distance of 270 km to the east (despite the distance, with favorable weather conditions you can see the ocean from the summit).

Administratively, the mountain is part of the Kilimanjaro region, straddling Hai, Moshi Rural and Rombo districts, where the highest point and most of the mountain is located. It is fully included in the Kilimanjaro National Park.

Topography

Kilimanjaro is a stratovolcano with a generally conical shape. It consists of three peaks, two of which are also extinct volcanoes: 3962 m Shira in the west and Mawenzi in the east, with 5149 m, and a dormant volcano, Kibo, in the center, with 5891.8 m .

Kibo is crowned at the summit with an elliptical caldera, 2.4 km long and 3.6 km wide, enclosing a crater called Reusch crater, 900 m in diameter, with a cinder cone in the center, 200 m in diameter, called the Ash Pit. The main summit, on the southern edge of its outer crater, is called Uhuru Peak; Other notable points of the Kibo are the Inner Cone, at 5835 m altitude; the Hans Meyer point, the Gilman point, the Leopardo point and the Yohanas gap, named after the guide who accompanied the first ascent of the mountain. To the southwest of the summit, a large landslide gave birth, about 100,000 years ago, to the Western Breach) that dominates the Barranco Valley (Barranco Valley).

Mawenzi is sometimes considered the third highest peak on the African continent, after Mount Kenya. It is badly eroded and today has the appearance of a dyke featuring Hans Meyer Peak, Purtscheller Peak, the South Peak and the Nordecke Peak. At its base, several ravines start to the east, especially the Great Ravine (Great Ravine) and the Barranco Menor (Lesser Ravine). The Saddle, is a 3600 ha plateau located between the Mawenzi and the Kibo.

The Shira, in which the Johnsell point stands out, is made up of a deformed semi-crater of which only the southern and western edges remain. In the northeast of it, on about 6200 ha, the mountain has a plate-shaped surface. About 250 satellite cones are present on both sides of these three peaks, on a northwest/southeast axis.

Hydrology

The Kilimanjaro ice cap is confined to Kibo; in 2003 it covered an area of two square kilometers. It is made up of the Furtwängler glacier at the summit, the Drygalski, Great Penck, Little Penck, Pengalski, Lörtscher Notch and Credner glaciers at the level of the northern ice field (in English Northern Icefield), the Barranco glaciers (or Little and Big Breach), Arrow and Uhlig to the west, Balletto, Diamond, Heim, Kersten, Decken, Rebmann and Ratzel at the level of the southern ice field (Southern Icefield) and finally the Eastern Icefield. The geographic variability of precipitation and insolation explains the difference in size between the different ice fields.

This ice cap was once clearly visible, but is shrinking dramatically. It covered an area of 12.1 km² in 1912, 6.7 km² in 1953, 4.2 km² in 1976 and 3.3 km² in 1996. During the 20th century, it lost 82 % of its surface, about seventeen meters thick on average between 1962 and 2000. It is increasingly tenuous and, if current weather conditions persist, it is estimated that it will disappear completely by 2020 according to experts from NASA and the paleoclimatologist Lonnie Thompson, a professor at Ohio State University, or to 2040 according to an Austrian scientific team at the University of Innsbruck, or to 2050 according to the California Academy of Sciences. Ice on some slopes could last a few more years due to different local climatic conditions. The current situation would be comparable to what existed 11,000 years ago, according to the results of the extractions of various ice cores.

The ice cap has been decreasing since about 1850 due to a natural decrease in precipitation of the order of 150 mm, but this trend has accelerated noticeably during the XX century. Current climate warming is generally cited as the cause of this rapid disappearance, with the current dramatic decline in the ice sheet being noted as particularly notable considering it has continued for at least 11,000 years and survived a prolonged drought about 4,000 years ago that lasted more than 300 years. Thus, the mean daily temperature has risen 3 °C over the last thirty years in Lyamungu, to 1230 m altitude on the southern slope. However, the temperature remains constantly below 0 °C to the altitude where the glaciers are located, so Georg Kaser of the University of Innsbruck and Philip Mote of the University of Washington indicated that the strong regression of the glacier was mainly due to a drop in precipitation. this would join a local evolution caused by deforestation that translates into a reduction in the wooded vegetation cover and a decrease in environmental humidity. A parallelism is evident between the decrease of the ice cap and the rate of forest regression, more intense especially at the beginning of the XX century and in the process of stabilization. The characteristic appearance with walls of vertical edges of the ice on the summit shows that the glacier is sublimated by solar radiation, after a few wet decades in the XIX; this phenomenon is probably accelerated by a small decrease in albedo during the 20th century, particularly in the 1920s and 1930s. Another phenomenon that leads to the reduction of the ice cap is caused by the absorption of heat from the volcanic rock on which they are based and its diffusion at the base of the glaciers; they melt, become unstable and fracture, increasing the surface area exposed to solar radiation.

The watercourses resulting from the thawing of the ice significantly feed two rivers in the region, but 90% of the precipitation is absorbed by the local forests. Therefore, the disappearance of glaciers should not have a lasting direct impact on local hydrology, contrary to deforestation and anthropogenic pressure that has resulted in a four-fold increase in the diversion of water for irrigation since the end of the century XX. Kilimanjaro's forests receive 1.6 billion cubic meters of water per year, including 5% from precipitation produced by contact of fog clouds with the forest. Two thirds return to the atmosphere through evapotranspiration. The forest thus plays a triple reserve role: in the soil, in the biomass and in the air. Since 1976, precipitation by contact with fog clouds has decreased on average by twenty million cubic meters per year, that is, approximately the volume of the current ice cap every three years, which represents 25% less water supply in thirty years, equivalent to the annual drinking water consumption of one million chaggas.

Geology

Tectonics

During the Jurassic and Cretaceous, severe erosion took place in the region corresponding to present-day Kilimanjaro, and a plateau composed of gneiss and granulite dating to the Precambrian was formed below. The relief gradually flattened from the Paleocene: plains were formed to the north and east; inselbergs appeared in the northwest and southeast; and crystalline alluviums were evacuated to the south.

The Great Rift Valley, which runs through East Africa from north to south, originates in the Miocene with the start of the split of the Somali plate from the African plate. In the region that corresponds to an eastern branch of this rift, faults appear in the Pliocene and alluvium accumulates, covering most of the inselbergs. The faults encourage the opening of the graben and the increase of magma. Kilimanjaro and Mount Meru emerge at the level of a graben that takes a west-north-west/east-south-east direction, forming the threshold of Amboseli.

Orogenesis

The volcanism of Kilimanjaro began during the Pliocene and the creation of its edifice (the structure of a volcano is known as a volcanic edifice) took place in four major phases that emitted a total of 5000 km³ of volcanic rocks. The last three formed the imbricated stratovolcanoes that make up Shira, Kibo and Mawenzi. The WNW/ESE oriented rift that crosses them also gave rise to numerous satellite cones, divided into approximately eight zones. Eruptive vents located on the summit appear to have been active during the Holocene.

- Birth of the paleovolcano of Kilema

This phase, probably from more than 2.5 million years ago, is poorly known due to the small number of radiometric dates carried out on the volcano and the burial of the lava flows under other more recent ones, however several geomorphological indications support its existence.

Strates produced by inverted relief are found at the level of the Kilema ridges in the south, Kibongoto in the southwest, and Ol Molog in the northwest. The modeling of the building that would be responsible for the above, allows us to determine that the lava flows come from rifts and filled the main faults of the tectonic rift.

To the west, between the Ol Molog and Kibongoto ridges, the particular relief in the shape of a collapsed caldera or natural circus welcomed the Shira, which partially filled it. The product of erosion was evacuated to the west and later covered by Mount Meru. It is responsible for the unique orientation of the rift in the region.

A relatively similar relief, marked by the Ra depression, can be found to the south, between the Kibongoto and Kilema ridges. It is filled in part by the products of the Kibo, located at its northern end. However, further south, on the shores of the Nyumba ya Mungu reservoir, various volcanic deposits could confirm the hypothesis of a venting of the southern slope of the paleovolcano.

The volume emitted by this paleovolcano could represent about two-thirds of the current volume.

- Birth of the Shira

This event dates back to between 2.5 and 2 million years ago; it was characterized by significant volcanic releases along and along the Ol Molog (or North Shira) and Kibongoto Ridges, oriented roughly N-S. A relatively elongated basaltic (trachy-basalts, ultramafic, nepheline) shield volcano originates from pyroclastic flow, tuffs, and lava. At the same time, fissures in the ground reveal an accentuated inclination of the lava flows, showing that the building rises.

The Shira is characterized by a caldera open to the northeast but where the mountain walls are still strongly marked in the west and south. A hundred dikes, witnesses of the last activity of the Shira, rise in its center. Perhaps it was increased by an external caldera and some traces remain. Erosion, mainly glacial, and later emissions from Kibo significantly shaped the relief of Shira.

- Birth of the Mawenzi

This event dates back to between 1.1 and 0.7 million years ago, as a result of the eastward migration of magmatic processes at the level of the old Kilema ridge. This process occurs relatively weak but continuous and develops in two main stages. Initially, the Mawenzi receives basaltic intrusions whose structure is known as Neumann Tower as well as fine extrusions of trachy-basalts and trachyandesite that form cones and eroded necks: South Peak, Pinnacle Col and Purtscheller Peak. Post-volcanic erosion is very important and, due to the fineness of the materials (tuffs, ashes), the relief takes on a chaotic and very broken appearance, allowing the sheets to emerge. In a second moment, around 0.6 - 0.5 million years before our era, one or several pyroclastic flows arose from the northeastern edge of the 65-kilometre-diameter caldera. A Pelean eruption begins with pyroclastic emissions and lahars of which traces are found as far as Kenya. At the end of these eruptions, Mawenzi was subjected to a second erosion due to glaciation of the mountain.

- Birth of the Kibo

This event dates back between 0.6 and 0.55 million years and is the most well known. To date, five stages have been identified. Up to 0.4 million years before our era, a conical stratovolcano, comparable to Mawenzi, probably formed on the Kibongoto Ridge. The eruptions are irregular and favor erosion and moraine deposits generated by the first period of glaciation. They are made up of trachytes, oligoclase trachyandesites, trachybasalts and olivine basalts, with the presence of feldspar phenocrysts. They conclude with an explosive event called Weru Weru, based on pyroclastic stones and lahars, to the south and southwest of the caldera, as well as the first irruptions of secondary cones in the Ol Molog area. Between 0.4 and 0.25 million years BC, a new lava dome of trachytes and phonolites formed 1.6 km to the northeast. It emitted porphyry lava flows that caused the collapse of the building and the appearance of syenite intrusions. The second glaciation period caused further erosion. A lake is formed, as evidenced by the presence of pillow lavas. Between 0.25 and 0.1 million years before our era, Plinian-type eruptions occur. The repercussions reach as far as Kenya. Erosion caused by the third glaciation period leads to a partial subsidence and emptying of the elliptical caldera from 1.9 by 2.3 km, particularly by lahars and pyroclastic flows. Between 100,000 and 18,000 years, the current caldera and dome formed in the inside the remains of the previous one. The traces of phreatic eruptions and erosion validate the existence of the fourth and fifth glaciations, interspersed with more humid episodes with the existence of aquifers in the Holocene. Finally, between 18,000 and 5,000 years, Kibo is home to a lava lake. Its drainage creates the Pit Crater covering the summit with scoria, and the northern slope with lava flows.

Although there are no records of the last somital (summit) eruption, and it is currently considered inactive, Kilimanjaro still experiences some seismic shaking and sometimes emits fumaroles based on carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide and hydrochloric acid at the bottom of the Reusch crater, whose surface temperature reaches 78 °C. In 2003 it was concluded that magma was present at 400 m deep below the summit crater. Furthermore, several subsidences and landslides took place in the past, one of which created the Western Breach (western breach). The latest eruptions occurred along the Rombo Ridge and in the Lake Chala maar that measured 3.2 km in diameter, more than 90 m deep and located southeast of the volcano. They were of the Strombolian, Vulcan, or Hawaiian type, a succession of several types, or one of all three. This reflects the complexity of rift opening cycles, migration on the volcano's ridges, and magma differentiation. These eruptions created satellite cones hundreds of meters high.

Soil composition

Altitudinal Paleocene Cambisols attest to variation in forest cover. Thus, Kilimanjaro experienced periods favorable to the development of vegetation between −30,000 and −40,000 years and between −6000 and −8000 years. On the contrary, unfavorable cold periods imply strong erosion, mainly by solifluction. We still find these phenomena outside of today's glaciers. The study of the soils also reveals a greater seasonality than during the Pliocene.

Climate

The climate of the past

General information

In the past, the climate was determined using various methods, such as the study of lake levels, river flow, dune systems, the extent of glaciers or even the study of pollen. The more you go back in time, the closer the signals become. While the climate can be inferred for a given location as far back as 20,000 years, one must take into account the climate of virtually the entire African continent and then adjust the results using analogies to trace climate back to five million years. Difficulties associated with going back for such long periods include the uneven distribution of records and the lack of fossil vegetation due to unfavorable conditions.

Over large time scales, the climate is governed by orbital variations, which manifest the change in the amount of solar radiation reaching the Earth and play an important role in the weakening or strengthening of the monsoon. Some researchers, such as F. Sirocho and his team, suggest that the strength of the monsoons is related to the albedo in the Himalayas. Colder Northern Hemisphere winter temperatures lead to increased reflection of lightning off snow and ice, weaker summer monsoons, and eventually drier weather in East Africa. The strength of the monsoons is linked to orbital variations with a lag of around 8000 years. In general, the monsoon maximum occurs 2,500 years after a glacial minimum and corresponds to a minimum ocean surface temperature.

Since the beginning of the Quaternary, the Northern Hemisphere has had twenty-one major ice ages, felt as far as East Africa. Traces of these cooling climates in East Africa are found on Kilimanjaro, on Mount Kenya, in the Rwenzori and on Mount Elgon. They are all isolated pockets of similar alpine ecosystems, with identical fauna and flora. This means that the ecosystem has been broader, lower-lying, and must have covered each of these mountains. However, pockets of the current lowland ecosystem would have to survive, otherwise the species would become extinct in the future. this environment. An alternative explanation suggests that on this multi-million-year time scale, the probability that tornadoes would have carried flora and fauna to the mountains is high.

Regional climate history

At the beginning of the volcano's formation, 2.5 million years ago, the first of twenty-one major Quaternary glaciations occurred in the northern hemisphere, and tropical Africa experienced cooler temperatures than today. A million-year drier period follows, a trend that continues today globally.

150,000 years ago, the Riss glaciation maximum occurred, the penultimate major glaciation and the largest of the Pleistocene. It was followed by the Eem interglaciation, which was wetter and warmer than today. This was followed by an arid phase from −100,000 to −90,000 years is responsible for dune formation up to southern Africa, replaced by a short but intensely cold phase from −75,000 to −58,000 years. Towards the end of this period, the first of the Heinrich events (H6) occurs, releasing a large amount of ice into the North Atlantic, resulting in cooler temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere and a decrease in the intensity of the storm. monsoon. Other Heinrich events follow a drought associated with East African weather at -50, -35, -30, -24, -16 and finally, 12,000 years ago, in the Younger Dryas. Based on data collected in the Congo Basin, the period from −31,000 to −21,000 years was dry and cold, with a declining stratification of the vegetation. Forest species present in the high mountains were increasingly low-montane species, very widespread at low altitude. Lowe and Walker, however, suggest that East Africa was wetter than today. This discrepancy can be explained by the difficulty of associating different given geographic locations with dates.

The last great ice age lasted from −23,000 to −14,000 years with a very dry phase in Africa, with deserts extending hundreds of kilometers further south than at present. The summer monsoon is weaker, temperatures are 5 to 6 °C below current temperatures and there is a general retreat of the forest. Moraines dating to the end of the last glacial maximum in East Africa show that the southeast monsoon of the period is drier than the current northeast monsoon, already relatively dry. The strata could have big implications in this somewhat cold and rainy trend.

13,800 years ago, the climate turns humid and montane forests spread again. The monsoon strengthens, water levels lakes and river flows in East Africa are increasing. Alpine vegetation is limited by temperature rather than drought. Prior to the Younger Dryas, temperatures reach their present values, but forest cover remains incomplete, and when this period begins, the monsoon weakens and the level of the East African lakes decreases. Finally, the forests reach their current cover and density after the Younger Dryas, when the climate becomes humid. During the For the next 5,000 years the hygrometric trend continues globally despite new oscillations. Over the last 5,000 years and up to the present, the monsoon gradually weakens. A minimum of temperatures then ensues between 3,700 and 2,500 years ago during the Little Age of Ice, felt again between the years 1300 and 1900, while the permafrost subsists in the mountains.

Kilimanjaro Ice Ages

Glaciations in East Africa are associated with cooler and drier climates, with less precipitation remaining as snow. The strata that would have dominated during these glaciations could have had great implications in this cold and somewhat rainy trend.

Dating the glaciations of Kilimanjaro is possible through the study of its geomorphology: moraines, glacial valleys, glacial cirques, lakes of glacial origin. Thus, five glaciations have been revealed in the Kibo: the oldest dating from −500,000 years and has been certified at the foot of the site called Lava Tower, west of the summit; the second glaciation dates to −300,000 years and is clearly visible especially in the Bastion Stream, near the previous site, and around from the volcano, where it created U-shaped valleys, especially on the southern slope; the third ice age dates −150,000 years and probably remains one of the largest in the volcano's history; was followed by the fourth glaciation between −70,000 and −50,000 years which saw a strong advance in the southeast valley (South East Valley); the fifth ice age, approximately 18,000 years ago, is dated in the summit crater. A warmer cycle extends from −11,700 years, although the last series of minor glacial advances probably occurred in the Little Ice Age and left moraines on the bottom of existing glaciers. Only the last three glaciations are visible in the Mawenzi and only the third in the Shira, although there are indications of older glaciations.

Current weather

Temperature and precipitation

Weather conditions vary depending on the slopes of Kilimanjaro. Thus, on the southern slope, 850 mm of precipitation falls per year in Moshi, to 800 m altitude; 992 mm in Kikafu, at 960|m}} altitude; 1663|mm}} at Lyamungu, at 1230 m altitude, and 2184 mm at Kibosho, at 1479 m altitude. Meanwhile, on the eastern slope, 1484 mm falls in Mkuu, at an altitude of 1433 m (These data should be taken with caution due to the different methods used). The altitudinal maximum of precipitation is between 2400 and 2500 m altitude on the southern slopes and has not yet been determined on other slopes. In addition, the precipitation regime is more complex with the appearance of precipitation by contact of fog clouds with trees at forest level and then a sharp decrease with 1300|mm}} in the Mandara refuge at 2740 m, 525 mm at Horombo Hut, at 3,718m elevation and less than 200mm per year above Kibo Refuge, at 4630 m altitude. The convective exchanges that constitute the water cycle between the different levels of Kilimanjaro's vegetation are very important in bioclimatic terms.

At the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro, the average annual temperature is 23.4 °C although it is 5 °C at 4000 m altitude and −7.1 °C at the top of Kibo. Consequently, the adiabatic temperature gradient is about 0.6 °C per hundred metres.

Daily Variations

Between 4000 and 5000 m elevations, relative temperature fluctuations of 40 °C.

During the two rainy seasons, Kilimanjaro is almost always surrounded by clouds and precipitation can fall at any time of the day. In contrast, during the two dry seasons, the mountain experiences daily weather variations that follow a regular pattern: the morning is clear and cool with little humidity; the mountain is illuminated directly by sunlight and the temperature rises rapidly, reaching a peak between seven and ten o'clock. The difference is greatest towards 2800 m altitude. At the same time, the pressures usually reach their peak at ten o'clock. At low altitude, clouds begin to form. The anabatic winds caused by the hot rising air cause these clouds to progressively rise to the summit in the early afternoon, causing a gradual drop in temperature at mid-height. Between 10:00 and 15:00, humidity is lowest between 4,000 and 5,000 m altitude, and solar radiation on the ground is less intense. At sixteen hours, the pressure has a crest. The clouds continue to rise, finally arriving dry air currents from the east, leaving a clear day after 18 hours. Another temperature peak occurs between 3,200 and 3,600 m altitude.

Seasonal Climate System

- Contemporary model

Kilimanjaro is subject to a tropical savannah climate. It is characterized by a pronounced dry season, with mild temperatures, from mid-May to mid-October, and a short rainy season, from mid-October to late November, known as the "short rains" (short rains), followed by a warm and dry period from early December to late February and finally a long rainy season from March to mid-May, the «long rains» ( long rains).

The low pressure belt around the equator, known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) is responsible for alternating wet and dry periods. During the two dry seasons, the ITCZ is located over the Arabian Peninsula, in July, and between southern Tanzania and northern Zambia in March. When low pressures move from one extreme to another, the region has a rainy season. The amount of precipitation varies from year to year and depends on sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean and Indian Ocean, as well as the phenomenon known as El Niño. Warm waters and a strong Niño cause torrential rains.

Throughout the year, except in January, a localized low pressure over Tibet causes horseshoe-shaped winds from the Indian Ocean, below East Africa and into India. Locally, on Kilimanjaro, the effect gives prevailing southeasterly winds. In January, an inversion occurs with north-easterly winds. Kilimanjaro, rising steeply, becomes a major obstacle to those prevailing winds. During the rainy season, the monsoon in the Indian Ocean brings water-saturated, fully stratified, cloudy air. Most of the time it is deflected around the flanks of the mountain and eventually circumnavigates it, especially from June to October.

- The stations seen by the chagga

The main difference between the traditional seasonal pattern experienced by the Chagga and the modern view is the existence of a fifth season called “the season of clouds”, which derives from their knowledge of the low to mid altitudinal range in the southern and eastern slopes of Kilimanjaro. This season plays an important role for them in the agricultural cycle. In fact, the heavy rains produced by cloud contact in the cloud and mist forests not only help to regenerate the vegetation, but also feed the rivers that supply the irrigation canals below. On the eastern slope, along the Rombo Ridge, between Taraki and Mwika, this fifth season is limited from early July to mid-August, cloudless and subject to a strong easterly wind. This particularity can be seen in the vegetation.

The natives feel the bioclimatic changes through a persistent drying up, since the late 1960s, of the rivers that existed in the past almost continuously on the eastern slope. This finding is probably related to the drop in rainfall caused by deforestation, the retreat of glaciers, and their own arrangements to hoard the little water that still runs for one or two weeks a year. These changes also cause a decrease in hydroelectric potential, fishing, rice cultivation and sugar cane production in the surrounding regions.

Wildlife

Plains

The lowlands, roughly associated with the plains surrounding Kilimanjaro, lie between 800 and 1600 m high. altitude. The climate is very hot and dry. It is an open environment where fire, often started and controlled by Maasai herders, plays a major role. The vegetation consists mainly of savannahs with numerous herbaceous species (Hyparrhenia dichroa, Hyparrhenia rufa, Pennisetum mezianum, Pennisetum clandestinum ), flowering plants (Trifolium semipilosum, Trifolium usambarense, Parochetus communis, Streptocarpus glandulossinus, Coleus kilimandscharica, Clematis hirsuta, Pterolobium stellatum, Erlangea tomentosa, Caesalpinia decapetala), baobabs (Adansonia digitata), shrubs (Commiphora acuminata, Stereospermum kunthianum, Sansevieria ehrenbergii) and thorny plants (Acacia mellifera, Acacia tortilis, Commiphora neglecta) found below 1400 m altitude to the west and 1000 m altitude to the east. These trees and shrubs are used by local populations for domestic purposes (food, medicine, firewood, fodder, making closures, etc.) or for crafts (making works of art) and the deforested plots are transformed into irrigated crop fields.: garden crops, cereals (pigeon pea, beans, sunflower, finger millet, corn, etc.), bananas, coffee trees, avocados or eucalyptus.

The vegetation of the plains is home to numerous birds, such as the orange bulbul (Pycnonotus barbatus), the Heuglin's cosifa (Cossypha heuglini), the common mouse-bird (Colius striatus) or the tanned suimanga (Nectarinia kilimensis), and mammals such as the greater silver bushbaby (Otolemur monteiri), the four-legged fringed (Rhabdomys pumilio), aardvark (Orycteropus afer), Kirk's dik-dik (Madoqua kirkii), sitatunga (Tragelaphus spekii), the broad-tailed galago (Otolemur crassicaudatus) or the tree hyrax (Dendrohyrax arboreus) pursued by the genet (Genetta genetta).

Mountain

The tropical forest, located approximately between 1600 and 2700 m altitude, is divided into four distinct zones. The montane forests are vulnerable due to human activity (deforestation at the lower limit, arson at the upper limit) and the belt that forms it is very uneven in size; to the north and west it is very small. Forest fragmentation is responsible for a perceptible extinction of large mammal species.

The forest is home to different species of primates, such as the Diadem guenon (Cercopithecus mitis), the Angolan (Colobus angolensis) and Abyssinian (Colobus guereza) colobus ) as well as the olive baboon (Papio anubis). Among the other mammals, the leopard (Panthera pardus pardus), the striped mongoose (Mungos mungo), the serval (Leptailurus serval), the red porcupine (Potamochoerus porcus), the ratel (Mellivora capensis) or the crested porcupine (Hystrix cristata) are difficult to observe although they are often seen venture into the savannah. Silver-cheeked hornbill (Bycanistes brevis), Hartlaub's Turaco (Tauraco hartlaubi), Schalow's Turaco (Tauraco schalowi), Violet Turaco (Musophaga violacea), African Blue Flycatcher (Elminia longicauda), African Long-tailed Monarch (Terpsiphone viridis), the Common Mousebird (Colius striatus) and Rüppell's Cosifa (Cossypha semirufa) are bird species well adapted to life in the thick canopy.

- The dry jungle

This forest is threatened by its long periods of vegetative rest and in reality it only exists in a vestigial state; it has been almost completely replaced by irrigated foothill crops. The species that compose it are Terminalia brownii, Stereospermum kunthianum and several of the genus Combretum.

- The rainforest

Located to the south and east of the volcano, it forms a large crescent stretching from Sanya Juu to Tarakea. It is highly dependent on rainfall produced by contact of fog clouds with the forest but tolerant of drier periods. It receives an average of 2,300 mm of rain per year. The flora varies depending on the amounts of water received and the altitude; In this forest we can find Juniperus procera, Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata, Olea welwitschii, Albizia schimperiana, Terminalia brownii, Ilex mitis, Ocotea usambarensis, Euclea divinorum, Prunus africana, Agauria salicifolia, Croton macrostachyus, Croton megalocarpus, Macaranga kilimandscharica, Impatiens kilimanjari, Viola eminii or Impatiens pseudoviola, as well as species of the genera Combretum, Pittosporum, Tabernaemontana or Rauvolfia. This forest is under strong demographic pressure, particularly in the south, where a large number of plantations have been introduced among the wild species. Some plots are used for forestry and introduced species such as the Lusitanian cypress (Cupressus lusitanica) are threatened by the appearance of a species of aphids of the genus Aphis. While selective felling recovers quickly, clearcutting takes fifty years before seeing its plant diversity reappear. This progression of the upper agroforestry limit is stabilizing thanks to the qualification of the forest as a natural reserve and the awareness of local growers of the problem of water scarcity and soil acidification caused by deforestation. These two factors are also sometimes responsible for the parallel rise of the lower limit of the plantations that are replaced by the savannah. Recolonization plans favored by a better bioclimatic knowledge of the Chagga allow finding biological balances with tree species.

The Njoro forest, south of Moshi, has been a sacred forest for several centuries and also benefits from a protection status. Probably for these reasons it is the last rainforest that survives on the plain, although it suffers a slow decline. It consists mainly of shrubs of the species Newtonia buchananii.

- The fog forest

It is characterized by the presence of the species Podocarpus milanjianus and numerous epiphytes such as mosses and ferns that cover around 80% of the trees. This forest is present on the southern slope, between 2300 and 2500 m altitude. Water is provided almost exclusively by the circulation of humidity generated by evapotranspiration from the rain forest, which creates frequent fog. The dry season is very short and the uptake of suspended water is almost nil.

- The cloud forest

It contains Juniperus procera, as well as Afrocarpus gracilior, Hagenia abyssinica, white heather (Erica arborea, especially in its initial phase of development) and some mosses and lichens (Usnea articulata). This forest is found on the escarpments to the west, north, and northeast, generally between 2,500 and 2,700 m elevation. Unlike the cloud forest, it has a long dry season and the humidity does not circulate by convection, but by the precipitation produced by the contact of the cloud clouds with the forest caused by the strong winds from the east in the form of strata that can constitute the 60% of the water supply for plants. A good horizontal and vertical structuring of the forest is necessary so that it can filter well the suspended water particles.

Alpine zone

- The Brezales and the Machia

They are found between 2800 and 4000 m above sea level and receive between 500 and 1300 mm of precipitation per year. It presents a vegetation composed of heather, where the arborescent form of the white heather (Erica arborea) is the most characteristic, along with Erica excelsa. These two species are pyrophilic, and colonize burnt-out areas formerly occupied by cloud forest. In this way they saw their lower limit descend from 700 to 900 m of altitude depending on the areas under the effect of the pastoral anthropization of the Ongamo people for between 200 and 400 years depending on the slope. When the frequency of fires increases, only the grasses of the genera Hyparrhenia and Festuca manage to renew themselves. We also find flowering plants such as Protea caffra subsp. kilimandscharica and Kniphofia thomsonii. In some more protected areas, new natural species such as Pinus patula manage to develop, weakening the balance of the environment (decrease in biodiversity, impoverishment of soils), aggravated by its flammable nature. The willingness of the park authorities to fight the fires against the shepherds and beekeepers has a perverse effect: the environment between the upper limit of the forest and the heaths is not managed harmoniously and the fires are not controlled even though they are necessary for the survival of certain species. Thus, between 1976 and 2005, the area of the Erica arborea forest increased from 187 to 32 km², which is equivalent to a 15% decrease in the total vegetation cover of the mountain.

Numerous species of brightly colored birds from the Nectariniidae family populate the upper limit of the forest: Kilimanjaro sunbird (Nectarinia mediocris), olive sunbird (Nectarinia olivacea), sunbird Green-headed Suimanga (Nectarinia verticalis), Green-throated Suimanga (Nectarinia rubescens), Amethyst Suimanga (Nectarinia amethystina), Scarlet-breasted Suimanga (Nectarinia senegalensis), malachite sunbird (Nectarinia famosa), Fraser's sunbird (Anthreptes fraseri), tan sunbird (Nectarinia kilimensis), Tacazzé (Nectarinia tacazze) and Red-winged Suimanga (Nectarinia reichenowi). The same occurs with the long-crested eagle (Lophaetus occipitalis). aquilus, Dendromus melanotis and the naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber). On the other hand, mammals such as buffalo, lions, leopards, elephants, elands, duikers, and hyenas sometimes transit at this altitude to move from one point to another on the plain.

- Afro-Alpine zone

Its lower and upper limits are not clearly defined, but are generally between 4000−5000 m. It is characterized by a dry climate, with an average of 200 mm annual precipitation and significant differences in temperature. The plant species that live in this area are perfectly adapted to the rigors of the climate and some are endemic. Thus, we find Lobelia deckenii, the only alpine species of Lobelia that lives on Kilimanjaro. Dendrosenecio kilimanjari grows mainly in Barranco, which is more humid and protected than the rest of the mountain at the same height. Another species of asteraceae is Helichrysum kilimanjari. Some herbaceous tufts dot some humid meadows: Pentaschistis borussian and species of the genera Koeleria and Colpodium.

Only a few species of birds of prey are capable of reaching this altitude: the jackal buzzard (Buteo rufofuscus), the steppe eagle (Aquila nipalensis), the blue kite (Elanus caeruleus), the bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus) and the crowned eagle (Stephanoaetus coronatus); we also found two species of passerines: the Abyssinian Blacktail (Cercomela sordida) and the Cinnamon-breasted Bunting (Emberiza tahapisi).

Snow zone

Above 5000 m altitude there is practically no life. The little precipitation that does occur almost immediately seeps into the ground or accumulates in glaciers. However, Helichrysum newii was found near a fumarole of Reusch crater and some slow-growing lichens, such as Xanthoria elegans, which can live several hundred years at these altitudes. The only animal discovered to date at Kibo is a species of spider.

History

Progressive settlement

Kilimanjaro was probably the cradle of Maasai herders at the beginning of the Holocene, at a time when the foothills were wet and infested with tsetse flies, and where grasslands and high-altitude watercourses they could be a healthy environment for herds. The first archaeological traces of sedentarism around the mountain date to about 1000 years BC, with the discovery of stone bowls. The men who shaped them, hunter-gatherers, could have found an advantage there with the presence of fresh water and many other basic materials. The true settlement of the springs would date back to the first centuries AD, but no oral testimony confirms this. The Maasai peoples would not have finally migrated to the region until the 16th century. They were probably the main reason that would have pushed the Ongamo to retreat to the northeast since, according to their accounts, they occupied the northern slopes of the mountain for forty-four generations.

The Chagga have also resided north of Kilimanjaro. Its presence is attested in the south since the beginning of the XVIII century, although the birth of its people goes back centuries. VII and VIII. Their traditions evoke for some unoccupied lands and for others a reunion with "little men" called vakoningo or vatarimba. They might have withdrawn to caves in the middle of the forest or they would have been assimilated with their cattle and bananas forming the swai clan in Kimbushi. The distinction is clearly made with the vasi or mwasi, a hunting people known in East Africa through recitations in the Bantu language, and historically credited as Dorobbo. There was very limited unity among the Chagga; thus, to designate their group they used the term wandu wa mdenyi (the "people of the bananas"). This is probably due to their different origins: wakamba, taita (dawida), maasai (parakuyo, kisongo). Its basic social unit was the patrilineal clan, whose geographical limits were generally established by streams or watercourses. Several hundred have been identified. The clans have been progressively linked to chiefdoms (uruka or oruka) that have seen their importance increase with the emergence of conflicts, probably related to the ivory trade and trafficking in slaves.

Discovery and exploration

During Antiquity, a few chroniclers —like the Greek merchant and explorer Diogenes, around the year 50 in his work Travels in East Africa, or like the Egyptian geographer Ptolemy, in the middle of the centuryII on a map where he made the mountains of the Moon appear, according to the information they had obtained from Marine of Tyre-, mention the existence of a "white mountain" or "snow-capped" in the heart of Africa.

Later, although it could serve as a reference point for caravans of Arab traders, no reference is made to the mountain for centuries. Only at the end of the XIII century does the Arab geographer Abul Fida vaguely evoke a white-colored inland mountain. At the same time, a Chinese chronicler wrote that the country to the west of Zanzibar "extends to a great mount". the work Suma de Geografía: «To the west [of Mombasa] is the Olympus of Ethiopia, which is very high, and beyond are the mountains of the Moon where the sources of the Nile are. there is a great quantity of gold and wild animals in the region". /i>, is covered in red coral.

In 1840, the Church Mission Society decided to undertake the evangelization of East Africa. Thus Johannes Rebmann, a German missionary trained in Basel, was sent to Mombasa in 1846 in order to support Johann Ludwig Krapf, sick with malaria. On April 27, 1848, accompanied by Bwana Kheri and eight indigenous people, he set out to discover the Chagga kingdom of Kilema, which he and Krapf had heard of on the coast and which only Arab slavers would have entered. On May 11, unexpectedly, at only 28 years old, this mountain formed by a white dome:

Around 10 o'clock, I saw something very white at the top of a high mountain and I believed at first it was clouds, but my guide told me it was cold, so I gladly recognized this old company of Europeans called snow.Vers 10 heures, je vis quelque chose de remarquablement blanc au sommet d'une haute montagne et crus d'abord qu'il s'agissait de nuages, mais mon guide me dit que c'était du froid, alors je reconnus avec délice cette vieille compagne des Européens qu'on appelleJohannes Rebmann, Church Missionary Intelligencer

His attention was completely focused on the presence of snow that surprised him at that latitude. He asserted that the unknown nature of it was the object of many beliefs and was attributed by the natives to spirits.He returned to Kilimanjaro in November and found more favorable weather conditions for observation. He then described two main peaks, one conical and the other taller, forming a dome, rising above a common base about 25 miles long (40 km) and separated by a depression in the shape of "saddle" from 8 to 10 miles. The finding, reported in London in April 1849, was widely contested. No one wanted to believe that perpetual snow existed in that area of Africa, despite the fact that it was confirmed six months later by Krapf, who by then had also discovered them on Mount Kenya. Violent polemics pitted Cooley against Rebmann.

In 1856, Kilimanjaro was depicted for the first time on the "limace chart", drawn by Rebmann and Erhardt. The controversy fueled the curiosity of geographers and several expeditions followed one another, such as that of the English explorers John Hanning Speke and Richard Francis Burton in 1858. The latter stated that the sources of the Nile should be sought near the mountain. Henry Morton Stanley even confirmed its discovery by Speke in 1862. Finally, it was in 1861 the expedition of the German baron Karl Klaus von der Decken, accompanied by the young English botanist Richard Thornton, which allowed confirmation by observation of 2460 m altitude the existence of snow on the summit. The following year Decken managed to ascend to 4260 m and make the first topographic and hydrographic maps of the summit. They were only approximate but allowed, for the first time, to confirm the volcanic character of Kilimanjaro.

For several decades, however, access to Kilimanjaro remained difficult. The path from the coast to the mountain was long and full of pitfalls: wild animals, thieves, and the harshness of the climate. In addition, the caravans were reluctant to go up because of their fear of Maasai warriors, and the incessant wars between the Chagga created insecurity, as evidenced by the fatal wound they inflicted on Charles New, an English missionary sent by Decken.

First ascents

Scottish scientist and explorer Joseph Thomson observed the northern slopes from Maasai territory in 1883 and attempted the ascent to the summit, although he failed to reach more than 2700m altitude. He was followed in 1887 by the Hungarian count Sámuel Teleki, with the Austrian Ludwig von Höhnel, but they did not exceed 5300 m due to of the pain in the eardrum suffered by Teleki. On November 18, 1888, Otto Ehrenfried Ehlers reached 5740 m altitude, despite claiming to reach 5904 m (higher than the actual altitude of the summit).

The German geologist Hans Meyer, although advised by Teleki, failed in 1887, in his first attempt, at 5400 m altitude. He started again the following year, accompanied by the Austrian geographer Oscar Baumann, but both were taken prisoner during the Abushiri revolt and had to pay a ransom of 10,000 rupees . After these two failures, Meyer decided to bring his friend Ludwig Purtscheller, an Austrian mountaineer, and Yohan Kinyala Lauwodu, a Chagga soldier from the army in Marangu. The expedition was organized before his departure by W. L. Abbott, a naturalist who had already studied the mountain well. Properly prepared and subjected to strict discipline, they finally reached the Kibo crater at 5860 m altitude on 3 October. Meyer's experience was decisive in the choice of places to establish supply camps that supplied the porters along the route, in order to alleviate food shortages in case of repeated attempts. The men realized that to climb the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Spitze (now Uhuru Peak), they had to go around the rocky ridge. They reached the summit on October 6, 1889 after spending several hours carving steps into the ice with ice axes the previous days. They then began the ascent of Mawenzi, spending a total of more than sixteen days at 4000m altitude, facing temperatures approaching −14 °C. The ascent of Uhuru Peak was not achieved again until twenty years later by M. Lange.

At the turn of the 20th century, Germans began building mountain huts, such as the Bismarck hut, at 2550 m elevation, and the Peters Refuge at 3450 m. The Refuge Kibo was built in 1932.

The Mawenzi was successfully ascented on July 29, 1912 by the Germans Fritz Klute and Eduard Oehler. The fragility of its rocks makes the ascent very difficult. The two men took the opportunity to make the third ascent of the Uhuru peak, the first on the western slope. A few weeks later, Walter Furtwängler and Siegfried König descended the Kibo on skis. Frau von Ruckteschell became the first woman to reach the Gilmann point.

World War I suspended promotions. In 1926 the Protestant pastor Richard Reusch discovered a frozen leopard on the edge of the Kibo caldera, from which he took an ear as evidence, which inspired a novel by Ernest Hemingway. The following year, he descended to the bottom of the crater that will later bear his name. He made a total of forty ascents.In 1927, a British trio chained Mawenzi and Kibo, making Sheila MacDonald the first woman to climb Uhuru Peak.

Religious missions

Evangelization began at the end of the 19th century in an environment of perpetual clan strife and colonization. Catholics and Protestants strove to explore, start conversations, acquire land, teach languages, set up schools, clinics, and orphanages, cultivate the land, and build places of worship. The Chagga seem to have been fond of reading and writing. Despite this, missionaries of both religions suffered many human and material losses as political tensions fluctuated with the traditional and colonial authorities.

In 1885, the first Protestant post was opened in Moshi. Mandara, the king of Moshi, received, at his own request, Christian teachings from Bishop Hannington of the Church Mission Society and Reverend Fitch. He decided the following year to allow the construction of a school for boys. However, things got complicated for the British missionaries, positioned between the indigenous and the German colonial forces, and they were replaced in 1892 by Lutherans from Leipzig, who were active during the protectorate. Riots in 1893 caused the burning of Moshi and various herdsmen settled alternately in Machame, Mamba, Mwika, Old Moshi and finally in Masama in 1906. In 1908, ten years after the first baptisms, 53 Chaggas adopted the protestant religion. During World War I German missionaries were confined and later expelled. The first Chagga herdsman took office in 1932.

The Protestants had some rivalries with the Spiritan fathers, who came from La Réunion and settled on both sides, east and west, of the mountain, but they maintained respectful relations with them. Little by little, the latter give reason, before the Holy See, to the Comboni Missionaries installed in the Sudan region along the Nile, as well as to the Bavarian Benedictines, who argued their adaptation to the mountain environment. They also made beautiful engravings of Kilimanjaro which they published in the Nassauer Bote and in the calendar of Saint Odilia. Unsuccessful attempts, they headed from 1877 towards the western plateaus, driven by propaganda and later called by Baron von Eltz established in Moshi, who wanted to found a colony of Polish Catholics on Kilimanjaro and required the services of a priest. He addressed Monsignor de Courmont, who began a study trip with Fathers Auguste Gommenginger and Le Roy, considered essential for learning about the mountains and which marked the establishment of the Catholic Church. The latter wrote in 1893 Au Kilima-Ndjaro. Courmont made numerous sketches, whenever the weather improved, and wrote on March 1, and then December 1, 1890:

For two years we were planning a foundation for Kili. But how to get there in a region where hostilities always reign? On the other hand, the immense and fertile plains of Tana were open to us [...] Reverend Leroy [is] our main intermediary among the indigenous, as he speaks the language very well.Depuis deux ans nous projetions une fondation au Kili. Mais comment y arriver par une région où régnaient toujours les hostilités ? D'autre part, les immenses et fertiles plaines de Tana nous étaient ouvertes [...] Le R.P. Leroy [est] notre principal entremetteur auprès des indigènes dont il parle très bien la langue.

So in the failed Tana; disappointment in Sobaka. There's Kilima Ndjaro.

I decided to do the exploration, in the company of two of our Fathers. It was organized quickly and the circumstances have wanted the mission to be, without further delay, begun in September.

The country [...] is formed by a magnificent mountain range, dominated by two peaks, the Kibo, 6000 m and the Kima, 5300. It is fertile, healthy and very populous.

The Washaga, or indigenous blacks of the mountainous region, are intelligent, laborious, eager to learn. His numerous sons run around the missionaries, without revealing too much this wild nature that, after a first curiosity is satisfied, scattered them [...] We can augur well for this mission, especially if Ndjaro Kilima becomes, as mentioned, a country of emigration for a laborious population of German Catholic peasants.

However, the distance from this point makes it difficult to organize and send caravans also makes this foundation a work that will require more sadness, sorrow, tribulations of all nature and more considerable dispensations. But we have confidence in God, and that's why we'll even go forward.Ainsi sur le Tana insuccès; déception sur le Sobaki. Restait le Kilima Ndjaro.

Je résolus d'en faire l'exploration, en compagnie de deux de nos Pères. Elle fut rapidement menée et les circonstances ont voulu que la mission pût être, sans plus de retard, commencée au mois de septembre.

Ce pays [...] est formé d'un magnifique massif de montagnes, dominé de deux pics, le Kibo haut de 6000 mètres et le Kima de 5300. Il est fertile, sain et très populeux.

Les Washaga, ou noirs indigènes de la région montagneuse, sont intelligents, industrieux, désireux de s'instruire. Leurs enfants nombreux s'empressent autour du missionnaire, sans trop révéler cette nature sauvage qui, après une première curiosité satisfyite, les disperse [...] Nous pouvons donc augurer beaucoup de bien de cette mission, surtout si le Kilima Ndjaro devient, comme il en a été question, un pays d'émigration pour une population laborieuse de paysans catholiques allemands.

Toutefois, l'éloignement de ce point qui rend difficiles l'organisation et l'expédition de caravanes fait aussi de cette fondation une œuvre qui demandera plus de peines, d'ennuis, de tribulations de toute nature et des dépenses plus considérables. Mais nous avons confiance en Dieu, et c'est pour cela que nous allons quand même de l'avant.Monsignor of Courmont, Annales apostoliques

In 1891 the first Catholic mission was created in Our Lady of Lourdes in Kilema, at the foot of the Kibo, whose grace is mentioned several times in correspondence. Little by little, a network of parishes was established on the slopes of the volcano, initially with a majority of Alsatian missionaries. Full-fledged communities are born around each mission, where education and commerce are promoted, especially coffee. A second mission was implanted in Our Lady of the Liberation of Kibosho, in 1893, in a place coveted by the Protestants, assuring their domain in the heart of the mountain. At the beginning of the 20th century, Kibosho regularly hosted 3,000 young people in 22 schools. In 1898, the mission of Rombo (Fisherstadt) was born in turn, followed later, in 1931, by Nuestra Señora de las Nieves in Huruma. Several annexes were erected in independent missions: in 1912 Uru, and later Umbwe, entrusted to African priests; in 1912, Mashat became independent from Rombo (despite a closure between 1922 and 1926); in 1947, Narumu and Kishimundu (Uru affiliate) seceded from Kibosho; also in 1947, Kirua, Marangu and Maua, the "highest mission of Kilimanjaro", previously assigned to Kilema; and in 1950, Mengwe.

On September 13, 1910, a new organization was established. The propaganda, at the request of Monsignor Vogt, erected a new vicariate to the north of the Bagamoyo vicariate and gave it the name of the apostolic vicariate of Kilima-Ndjaro.

In 1998, of the 80 Tanzanian Spiritan priests formed in Moshi, none remained in the square. The old missions had already been ceded, but the sisters of the Congregation of Our Lady of Mount Kilimanjaro, founded in Huruma, continued to maintain an intense religious life. Among the Protestants, about 200 national pastors still officiated in the Moshi diocese. In the early 20th century, Greek Orthodox planters settled near the mountain and built places of worship, but their presence was temporary. and limited proselytizing. Its facilities were ceded to the Moshi Orthodox Church and sold to the Baptists with the authorization of a priest to perform services there.

The presence of all these religious communities left numerous works describing Kilimanjaro and have contributed greatly to the literacy of the region. In 1914, only 5% of the schools were secular and fifty years later, after independence, 75% of the primary schools and 50% of the secondary schools were founded by missionaries.

The mountain at the heart of international geopolitics

The discoveries of Johannes Rebmann and Johann Ludwig Krapf renewed the German Empire's interest in East Africa, as did the British Empire's in 1883: naturalist Harry Johnston was officially commissioned by the Royal Geographical Society to scale Mount Kilimanjaro and detail its flora and fauna; unofficially, he worked for the British secret services (MI6). East Africa Company (British East Africa Company). It is not without difficulties that alliances are organized with local leaders, constantly at war and supplied with weapons by Arab merchants. In the 1880s, the principalities of Kibosho under the reign of Sina and Moshi under that of Rindi, Mandara and later Meli clashed violently. The objectives progressively involve the States in a more direct way, with the Berlin Conference in 1884 and the signing the following year of an imperial letter of protection by Otto von Bismarck, guaranteeing the German possessions in the west of Dar es Salaam.. The Kilimanjaro corresponds to them by the game of alliances, and the British were withdrawn to the north. They got Mombasa "in compensation" on November 1, 1886 and the border results in two connecting segments ostensibly outlining the base of the northern slope of the volcano. Colonization becomes official on January 1, 1891, the date of the creation of a German protectorate. German East Africa continued until November 25, 1918, when it came under British control. It was divided seven months later, following the Treaty of Versailles, and was renamed the protectorate of Tanganyika, which acquired mandate status from the League of Nations in 1922.

On December 9, 1961, the independence of Tanganyika was proclaimed. On the same day, in response to the similar act of Hans Meyer in 1889, who signed the start of the German occupation of that territory, the flag of the new state was planted with a torch on top and was renamed Uhuru Peak, "peak of freedom." This symbol, requested by Prime Minister and future President Julius Nyerere, was meant to mark the end of racial inequality and the reappropriation of this symbol of Africa. Politically, it is the backdrop of the Arusha Declaration, proclaimed at its foot on February 5, 1967 by the party in power, the Tanganyika African National Union, and which defines the broad lines of the Ujamaa. Economically, it becomes a national tourism destination and is represented in many products manufactured in the country. But this brand image is poorly managed and hard currency escapes Tanzanians: guides and porters are poorly paid, trips are organized from the country of departure by foreign companies, the clientele is relatively unfortunate, the benefits do not match the expectations. Historically, the region turned towards the coast and the Kilimanjaro is "forgotten" in favor of the fine sand beaches and the great plains of an easier access. Kilimanjaro National Park, created in 1973, was designed to protect forest and water resources rather than encourage tourism. The authorities see this manna escaping to Kenya, to which tourist catalogs often attribute possession of the volcano. Rivalry with the more prosperous neighbor led in 1977 to the closure of the borders and the dissolution of the East African Community.

Population and traditions

Distribution and political organization

The Chagga are spread out along the southern and eastern slopes of Kilimanjaro. The first chiefdoms arose at the end of the 18th century, the work of the most influential men, who federated the clans around their project, often with young bachelors valid for war. One of the first great chiefdoms, which conquered the entire eastern slope through alliances with the Kambas, was that of Orombo, a chagga from Keni, but it collapsed after the death of his leader. The chiefdoms of Kilema and Machame, on the southern slopes, profited both from trade with the Europeans and from an alliance with the Maasai. Kibosho reached its height in 1870 under the reign of Sina, who traded with the Swahili. Moshi, early XX century, is supported by missionaries. These successive alliances and conquests allowed the Chaggas to mingle. However, the unity of the headquarters was slow to materialize. Only in the 1950s, with collective economic development and the appointment of a single boss for the first time in its history, did it become a reality. The catalyst for this awareness is probably to be found at the time when Westerners set their sights on "that tribe." Administratively, village boundaries (kijiji) are partly a reflection of ancient clans and chiefdoms, and were grouped into districts (mtaa or mitaa). i>).

The Ongamo who are currently concentrated in the Rombo region in the northeast are in the process of assimilation among the Chagga. They maintain a beekeeping and pastoral tradition at the upper edge of the forest. The Maasai occupy the foothills to the north and west of the mountains. Their lifestyles are increasingly influenced by the surrounding peoples and little by little they abandon their traditions: sedentary lifestyle, access to property or Christianization. The result is a marginalization of groups of agro-pastoralists or farmers.

Linguistics

The Chagga or Kichagga language is actually divided into three languages, Western Chagga, Central Chagga, and Eastern or Rhombo Chagga, each made up of several dialects. They are only relatively homogeneous with each other, to the point that people speaking two different Western Chagga dialects will have difficulty communicating and will face almost total misunderstanding if they talk to people who use Eastern Chagga. Western Chagga is subdivided into the Siha (in Kibong'oto), Rwa (Mount Meru, western slopes of Kilimandjaro), Machami (in Machame), and Kiwoso (in Kibosho) dialects; the central chagga in the uru, mochi (Old Moshi, Mbokomu), wunjo (Kilema, Kirua, Marangu, Mamba) dialects; Eastern Chagga in the North-Rhombus (Mashati, Usseri) and South-Rhombus (Keni, Mamsera, Mkuu) dialects. On the other hand, the Chaggas tribes distributed to the south and east of the mountain are related to Bantu (pare, wataita, wakamba) and nilotic (ongamo, masai) language peoples, and in the past with Cushite languages.

Education

Religious missions have contributed greatly to the literacy and modernization of the Chagga. At the same time, many of them have adopted Christianity. Thus, the Catholic Church can currently claim about 570,000 faithful in 39 parishes and 72 branches. The first school for boys was opened in 1894 in Machame. Ten years later, there were thirty Lutheran institutions with 3,000 students, 5,817 in 1909 and 8,583 in 1914 in a hundred schools. On the Catholic side, 2,300 boys and girls attended 22 schools in 1909 and two years later more than 7,000, in Kibosho and Rombo alone. Hostility from Western landowners, interfaith competition, the advent of Islam as well as the start of the First World War slowed down the development of schools. In the 1920s secular schools open their doors with a Chagga elite at the helm. In 1944, the new chagga council establishes a tax to finance its increase. The election in 1962 of Julius Nyerere (who had been a professor) to the presidency of the newly independent country, accelerated the trend.

Beliefs and rituals

Although Christianity is now the dominant religion, a background of traditional beliefs continues to exist in more rural areas. Chagga elders believe in the existence of witches (wusari) and that they have the ability to bring rain. They also see omens in dreams, worship ancestors, and believe that the dead influence their destiny. Their god is Ruwa and their mythology has many similarities to the Bible. They recognize the concept of sin and practice a kind of confession accompanied by infusions to avoid the victim's curse. The healer is in charge of this mission, which also has medicinal functions. According to their ancient traditions, only married couples are placed in a cowering position in funeral rites and buried facing the Kibo. The dead young and newborns are wrapped in banana leaves and deposited at the foot of a tree. Animal sacrifices are carried out during the nine days after the funeral to accompany the soul of the deceased. There is a relatively violent rite of passage called ngasi to mark the passage of children into adulthood (mbora). Marriages were arranged by families.

Traditional residence and agriculture

The typical property of the Chagga is constituted by a concession (muri or mri) in the center of which is the hut (mmba), devoid of walls and whose roof is made of wooden slats, thorny branches and straw that rests directly on the ground. Its shape is tall and conical in the eastern area, between the district of Rombo and Moshi, and vaulted in the west. The space in the back is shared with the animals (goats, cattle); the interior is reserved for human beings to eat, receive visitors, sleep and store household items. The bed is made from banana leaves covered with animal skin. The two spaces are separated by stakes and by the hearth (iriko), on which the fruits and firewood are dried. These traditional huts have been replaced by rectangular houses (nshelu, mtshalo or mshalo) made of bricks or concrete blocks, plastered and painted, with windows with glass and with the roof covered with a metal sheet. The concession is surrounded by a hedge (ndaala or waatha) of Dracaena steudneri to ensure its safety. Two courtyards surround the residence: an exterior one (mboo or nja) which is accessed through a portal (ngiri, kichumi or ksingoni) for children to play on, and an inner one (kari, kadi, mbelyamba or kandeni) on the back to extract seeds of all kinds (cereals, coffee). Annexes can also be built on the concession: barn, porch, or an auxiliary hut. The latter was used as the husband's house after many years of cohabitation, but the practice has disappeared.}

From the traditional perspective of the Chagga, the cultivated areas are situated on one side between the savannah (kasa, nuka, mwai) arid, insane, vector of fevers and traveled by Maasai warriors, and the mountain forest (nturu, mtsudu, msuthu) by another. Since the pre-colonial period, agriculture has been marked by a relatively intensive productive system, characterized by the use of cattle manure on already fertile soils. Among the main productions are firstly bananas introduced from Southeast Asia, probably by Arab traders in the VIII century; In addition to the fruit of this plant, called iruu or irubu, its leaves and fibers have multiple uses. Plantains are prepared in different ways, and can be eaten "on the tree", cooked or with beer, each with its own name, indicating its importance. Trees and their fruits are at the center of many traditions and mark events such as weddings, pregnancies, births and deaths. Bananas are transmitted by inheritance from parents to children. Tubers such as yams (kikwa, the local species resulting from crosses of Dioscorea cayenensis, Dioscorea abyssinica and Dioscorea alata), taro (Colocasia esculenta, called iruma, duma or ithuma) and more recently sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas known under the name of kisoiya) also play an essential role in the chagga diet. Two cereals are also cultivated: finger millet (vumbi or mbeke), native to a region between Uganda and Ethiopia, maize (maimba or mahemba, terms initially associated in other languages with sorghum) introduced by the Portuguese from the Antilles and later replaced by a variety from South Africa at the turn of the century XX and which sees its consumption increase even though it was absent from the chagga diet for a long time. The plots where the cereals and most of the tubers are grown are irrigated by true canal networks (mfongo) and generally left fallow after two or three years. The basic tools for working the soil are the hoe and the ax for clearing, along with the sickle. To the south, agriculture has been modernized (fertilizers, tractors, employment of hired labor) while it remains more traditional and mainly female to the east. The calendar is dictated by the seasons to which Kilimanjaro is subjected. The exploitation of a collection space close to inhabited areas, on the upper edge of the forest, has disappeared.

The introduction of coffee cultivation dates from the end of the XIX century, but its development only took place from the 1920. The number of farmers, some 600 in 1922, multiplied by twenty in the space of ten years under the impetus of a cooperative of small local producers. In the 1950s, the rise in the price of coffee allowed them to become rich and invest substantially in building new infrastructure and gaining greater political weight. These peasants became one of the pillars of the independence of Tanganyika and will paradoxically suffer its repercussions in the effort to modernize the country's economy.

Livestock farming is also essential for the Chagga. Cattle (zebus called ng'umbe), goats (mburu) and sheep (yaanri, ichondi or irohima) provides meat, milk and fresh blood. Poultry has traditionally been ignored in East African culture.

Activities

Protection of the environment

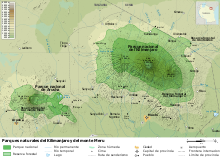

The protection of the natural environment of Kilimanjaro was carried out in several stages: in 1910, Germany created a first hunting reserve, which in 1921 was transformed into a forest reserve; in 1973, the area above 2700m elevation was declared a Kilimanjaro National Park, a park that was opened to the public four years later; In 1987, the boundaries of the park were extended to 1830 m altitude, reaching a protected area of 75 353 hectares. Finally, it was inscribed on the Unesco World Heritage List, with the justification that "Kilimanjaro, with its snow-capped peak that dominates the almost 5000 m, is the largest isolated mountain massif that exists" and that the park has "a great diversity of rare or endemic animal and plant species". gradually increased from 89,000 ha, first to 92,906 and then to 107,828 ha. The complex protects some 3,000 plant species.

In parallel to the work of the national park, several small-scale projects have been launched in order to improve the management of the forest with the help of the local population and to initiate reforestation programs. But satellite images show that fragmentation continues due to inexperience of forestry operators and few resources invested in fighting fires.

An eight-kilometre-wide biological corridor has been maintained to the northwest of Mount Kilimanjaro, in Maasai territory, to link the park with Amboseli National Park, across the Kenyan border, a corridor that facilitates the circulation of the twenty common species of large mammals of the twenty-five present in the montane forests.

Hiking and mountaineering

Mounting Kilimanjaro is very popular with many trekkers, especially those beginning the assault on the “Seven Summits”. Approximately 20,000 people every year cross the entrance to Kilimanjaro National Park and climb it. The best time is from July to October or in January and February to avoid the rainy season. The regulations of the park impose the hiking routes, the means to use in the ascent (guard, etc.) and the entrance fees. It is recommended to be accompanied by porters and possibly a cook, but the law requires that you be accompanied by an authorized guide. All climbs require a good physical condition, especially to prevent the so-called "altitude sickness". Although the risks are low, however, some tourists lost their lives in the ascent, by accident or due to lack of preparation; It is therefore advisable to be prudent and train before attempting it, since only 40% of the ascents are crowned with success. Guards are posted on the mountain to allow quick evacuation in an emergency.

Hiking routes

It takes six to ten days to reach the summit and back. The routes to the summit of Kilimanjaro mainly use the southern slopes of the volcano, and some are very popular. The routes on the north side are reserved for experienced mountaineers. There are seven starting points (gates) around the mountain and various variants.

- Route Rongai or route Loitokitok