Juana Ines de la Cruz

Juana Inés de Asbaje Ramírez de Santillana (San Miguel Nepantla, Tepetlixpa, November 12, 1648 or 1651-Mexico City, April 17, 1695), better known as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz or Juana de Asbaje, was a Hieronymite nun and writer from New Spain, an exponent of the Golden Age of literature in Spanish. She also incorporated classical Nahuatl into her poetic creation.

Considered by many as the tenth muse, she cultivated poetry, auto sacramental and theater, as well as prose. At a very early age she learned to read and write. She belonged to the court of Antonio Sebastián de Toledo Molina y Salazar, Marquis of Mancera and 25th Viceroy of New Spain. In 1669, out of a yearning for knowledge, she entered monastic life. Her most important patrons were the viceroys De Mancera, the viceroy archbishop Payo Enríquez de Rivera and the marquises of Laguna de Camero Viejo, also viceroys of New Spain, who published the first two volumes of her works in Spain. peninsular. Thanks to Juan Ignacio María de Castorena Ursúa y Goyeneche, bishop of Yucatán, the work that Sor Juana had unpublished when she was sentenced to destroy her writings is known. He published it in Spain. Sor Juana she died from an epidemic on April 17, 1695 in the Convent of San Jerónimo.

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz occupied, along with Bernardo de Balbuena, Juan Ruiz de Alarcón and Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, an outstanding place in New Spanish literature. In the field of poetry, her work is ascribed to the guidelines of the Spanish Baroque in its late stage. Sor Juana's lyrical production, which accounts for half of her work, is a melting pot where the culture of a New Spain at its peak, the culteranismo of Góngora and the conceptualist work of Quevedo and Calderón converge.

Sor Juana's dramatic work ranges from the religious to the profane. Her most notable works in this genre are Love is more of a labyrinth , The pawns of a house and a series of sacramental acts designed to be performed at court.

Biography

Controversy of his birth

Until almost the middle of the 20th century, Sor Juana critics accepted as valid the testimony of Diego Calleja, the nun's first biographer, regarding her date of birth. According to Calleja, Sor Juana would have been born on November 13, 1651 in San Miguel de Nepantla. In 1952, the discovery of a baptismal certificate that supposedly belonged to Sor Juana pushed back the date of the poet's birth to 1648. According to said document, Juana Inés would have been baptized on December 5, 1648. Several critics, such as Octavio Paz, Antonio Alatorre, and Guillermo Schmidhuber, accept the validity of the baptismal certificate, as well as Alberto G. Salceda, although the Cuban scholar Georgina Sabat de Rivers considers the evidence provided by this act to be insufficient. Thus, according to Sabat, the baptismal certificate would correspond to a relative or a French woman. According to Alejandro Soriano Vallés, the most acceptable date is 1651, because one of Sor Juana's sisters supposedly gave birth on 19 September. March 1649, making it impossible for Juana Inés to have been born in November 1648. (This supposition of 1651 is not based on probative documents, but on suppositions based on the date reported by Diego Calleja in 1700. However, the finding by Guillermo Schmidhuber of the Faith of baptism of "María hija de la Iglesia" in Chimalhuacán dated July 23, 1651, belonging to Sor Juana's younger sister, makes the birth of the Tenth Muse impossible in 1651 because the womb of the mother was occupied by another girl, that is, her sister Maria).

The researcher doctor Lourdes Aguilar Salas, in the biography that she shares for the University of the Cloister of Sor Juana, indicates 1651 as the most correct. In fact, what Alejandro Soriano maintains had already been stated previously by Georgina Sabat de Rivers, and he only later took up the argument of the renowned Sor Juana supporter, who personally favored the year 1651 because, when the date of baptism of Sor Juana's sister named Josefa María was known, March 29, 1649, the proximity of These dates made it impossible to think of two births with such a brief difference (Note: the Baptism Certificate of Josefa María has never been located, the date of this girl's birth is an assumption that has not been substantiated in a document).

However, this argument is also inevitably relativized when we know that the term between birth and christening frequently was not only days away, but also months and even years, as we know from historian Robert McCaa, who starts from a direct study of the written sources of the time, that the baptismal certificates in rural areas were recorded in the books when the infants had been several months to one or several years after being presented for baptism. The discovery of the certificate of Chimalhuacán by the historian Guillermo Ramírez Spain was published by Alberto G. Salceda in 1952; in it Sor Juana's uncles appear as godparents of a girl noted as "daughter of the Church", that is, illegitimate. Previously, only the biography of Sor Juana written by the Jesuit Diego Calleja and published in the third volume of Sor Juana's works: Fame and Posthumous Works (Madrid, 1700) had been used as a reference. However, existing documents are not definitive in this regard. On the one hand, Calleja's biography suffers from inaccuracies typical of the hagiographic trend of the time around prominent ecclesiastical figures; that is, the data is possibly modified with ulterior intentions. To give just one example, Calleja strictly fixes the day of Sor Juana's supposed birth on Friday, when November 12, 1651, the date noted by him, was not Friday On the other hand, the record of Chimalhuacán found in the 20th century presents little data about the baptized; if, as currently accepted, the December 1648 date is only the date of baptism, the date of birth may have been several months or a year earlier. Schmidhuber has discovered a second baptismal certificate from the parish of Chimalhuacán that says "María hija de la Iglesia", is dated July 23, 1651 and the name agrees with Sor Juana's younger sister; it is impossible that another girl was born the same year.

Until today, the most rigorous from the historiographical point of view is to remain in the dilemma between 1648 and 1651, as happens with countless historical figures whose dates of birth or death are not absolutely certain with documents available at that time. Adopting such a dilemma as a general rule does not affect studies on Sor Juana, neither in her biography nor in the evaluation of her work.

Early Years

Although there is little information about her parents, Juana Inés was the second of the three daughters of Pedro de Asuaje and Vargas Machuca (as Sor Juana wrote them in the Book of Professions of the San Jerónimo Convent). It is known that her parents were never united in an ecclesiastical marriage.

Schmidhuber has documented that the father arrived in New Spain as a child, as evidenced by the Passage Permit of 1598, in the company of his widowed grandmother, María Ramírez de Vargas, his mother Antonia Laura Majuelo and a younger brother Francisco de Asuaje who became a Dominican friar. His mother, Isabel Ramírez de Santillana, was the daughter of Pedro Ramírez de Santillana and Doña Beatriz Ramírez Rendón, residents of the town of Huichapan, belonging to the Marquesado del Valle. Around 1635 the whole family would emigrate to San Miguel Nepantla, to a farm called "La Celda", which Don Pedro Ramírez de Santillana would lease to the Dominicans.

In San Miguel Nepantla, in the Chalco region, his daughter Juana Inés was born on the "La Celda" hacienda. Her mother, shortly after, separated from Pedro de Asuaje and, later, had three other children with Diego Ruiz Lozano, whom he did not marry either.

Many critics have expressed their surprise at the marital situation of Sor Juana's parents. Paz points out that this was due to a “laxity of sexual morality in the colony.” It is also unknown what effect Sor Juana had on knowing that she was her illegitimate daughter, although it is known that she tried to hide it. This is how her will from 1669 reveals it: "legitimate daughter of don Pedro de Asuaje y Vargas, deceased, and doña Isabel Ramírez." Father Calleja was unaware of it, since he does not mention it in his biographical study. Her mother in her will dated 1687 acknowledges that all of her children, including Sor Juana, were conceived out of wedlock.

The girl spent her childhood between Amecameca, Yecapixtla, Panoaya —where her grandfather had a farm— and Nepantla. There she learned Nahuatl with the inhabitants of her grandfather's haciendas, where wheat and corn were grown. Sor Juana's grandfather died in 1656, so her mother took over her farms, and she learned to read and write at the age of three, secretly taking lessons with her older sister. from her mother.

Soon he began his taste for reading, thanks to the discovery of his grandfather's library and he became fond of books. He learned everything that was known in his time, that is, he read the Greek and Roman classics, and the theology of the moment. Her eagerness to know was such that she tried to convince her mother to send her to the University disguised as a man, since women could not access it. It is said that when studying a lesson, she cut a piece of her own hair if she he had not learned it correctly, since it did not seem right to him that the head was covered with beauty if he lacked ideas. At the age of eight, between 1657 and 1659, he won a book for a loa composed in honor of the Blessed Sacrament, according to his biographer and friend Diego Calleja. He points out that Juana Inés lived in Mexico City since she was eight years old, although there is more truthful news that she did not settle there until she was thirteen or fifteen.

Adolescence

Juana Inés lived with María Ramírez, her mother's sister, and her husband Juan de Mata. She may have been removed from her mother's estates because of the death of her maternal grandfather. She lived in the Mata house for approximately eight years, from 1656 to 1664. She then began her period at court, which would end with her entry into religious life.

Between 1664 and 1665, he entered the court of Viceroy Antonio Sebastián de Toledo, Marquis of Mancera. The viceroy, Leonor de Carreto, became one of his most important patrons. The environment and the protection of the viceroys will decisively mark the literary production of Juana Inés. By then she was already known for her intelligence and her sagacity, as it is said that, on instructions from the viceroy, a group of learned humanists evaluated her, and the young woman passed the exam in excellent condition.

The viceregal court was one of the most cultured and enlightened places of the viceroyalty. They used to hold lavish gatherings attended by theologians, philosophers, mathematicians, historians and all kinds of humanists, mostly graduates or professors from the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico. There, as a lady-in-waiting to the viceroy, the adolescent Juana developed her intellect and her literary abilities. She repeatedly wrote sonnets, poems, and funeral elegies that were well received at court. Chávez points out that Juana Inés was known as "the viceroy's very dear", and that the viceroy also had a special appreciation for her. Leonor de Carreto was the first protector of the girl poet.

Little is known about this stage in the life of Sor Juana, although one of the most valuable testimonies for studying this period has been the Response to Sor Filotea de la Cruz. This lack of data It has contributed to the fact that several authors have wanted to recreate Sor Juana's adolescent life in an almost fictional way, often assuming the existence of unrequited love.

Period of Maturity

At the end of 1666, she caught the attention of Father Núñez de Miranda, confessor to the viceroys, who, learning that the young woman did not want to marry, proposed that she enter a religious order. She learned Latin in twenty lessons taught by Martín de Olivas and probably paid for by Núñez de Miranda. After a failed attempt with the Carmelites, whose rule was extremely rigid and made her fall ill, she entered the Order of San Jerónimo, where discipline was somewhat more relaxed, and he had a two-story cell and servants. There he remained for the rest of his life, since the statutes of the order allowed him to study, write, celebrate gatherings and receive visits, like those of Leonor de Carreto, who never left his friendship with the poetess.

Many critics and biographers attributed her departure from court to a disappointment in love, although she often expressed that she was not attracted to love and that only monastic life could allow her to devote herself to intellectual studies. It is known that Sor Juana received a Payment from the Church for his Christmas carols, as well as from the Court when preparing loas or other shows.

In 1673 he suffered another blow: the viceroy of Mancera and his wife were relieved of their position and in Tepeaca, during the journey to Veracruz, Leonor de Carreto died. Sor Juana dedicated several elegies to her, among which "Of the beauty of Laura in love" stands out, the viceroy's pseudonym. In this sonnet she demonstrates her knowledge and mastery of the prevailing Petrarchan guidelines and topics.

In 1680, Fray Payo Enríquez de Rivera was replaced by Tomás de la Cerda y Aragón at the head of the viceroyalty. Sor Juana was entrusted with the making of the triumphal arch that would adorn the entrance of the viceroys to the capital, for which she wrote her famous Allegorical Neptune . She pleasantly impressed the viceroys, who offered her their protection and friendship, especially the viceroy María Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga, Countess of Paredes, who was very close to her: the viceroy had a portrait of the nun and a ring that she gave him. he had given as a gift and upon his departure he took Sor Juana's texts to Spain to be printed.

His confessor, the Jesuit Antonio Núñez de Miranda, reproached him for dealing so much with mundane issues, which together with the frequent contact with the highest personalities of the time due to his great intellectual fame, triggered the ire of this. Under the protection of the Marquise de la Laguna, he decided to reject him as a confessor.

The viceregal government of the Marquis de la Laguna (1680-1686) coincided with the golden age of Sor Juana production. He wrote sacred and profane verses, Christmas carols for religious festivities, sacramental plays (The divine Narcissus, Joseph's scepter and The martyr of the sacrament) and two comedies (Los empeños de una casa y Amor es más laberinto). She also served as the administrator of the convent, with good sense, and conducted scientific experiments.

Between 1690 and 1691 she was involved in a theological dispute as a result of a private criticism she made of a sermon by the well-known Jesuit preacher António Vieira that was published by the Bishop of Puebla Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz under the title Athenagorical letter. He prefaced it with the pseudonym Sor Filotea, recommending that Sor Juana stop dedicating herself to "human letters" and dedicate herself instead to divine letters, from which, according to the Bishop of Puebla, she would get the most benefit. the reaction of the poet through the writing Response to Sor Filotea de la Cruz, where she makes a fiery defense of her intellectual work and in which she claimed the rights of women to education.

Last stage

The last period of Sor Juana's life began in 1692 and 1693. Her friends and her protectors have died: the Count of Paredes, Juan de Guevara and ten nuns from the Convent of San Jerónimo. The dates coincide with an agitation in New Spain; rebellions take place in the north of the viceroyalty, the crowd assaults the Royal Palace and epidemics rage with the population of New Spain.

A strange change occurred in the poetess: around 1693 she stopped writing and seemed to dedicate herself more to religious work. To date, the reason for such a change is not known precisely; Catholic critics have seen in Sor Juana a greater dedication to supernatural issues and a mystical dedication to Jesus Christ, especially after the renewal of her religious vows in 1694. Others, on the other hand, guess a misogynistic conspiracy hatched in her against, after which she was sentenced to stop writing and was forced to fulfill what the ecclesiastical authorities considered the appropriate tasks of a nun. There have been no conclusive data, but progress has been made in investigations where the controversy that caused the Athenagorical Letter. his most famous phrases. Some claimed until recently that before her death she was forced by her confessor (Núñez de Miranda, with whom she had reconciled) to dispose of her library and her collection of musical and scientific instruments. However, a clause was discovered in the will of Father José de Lombeyda, a former friend of Sor Juana, which refers to how she herself commissioned him to sell the books so that, giving the money to Archbishop Francisco de Aguiar, he would help the poor.

At the beginning of 1695 an epidemic broke out that wreaked havoc throughout the capital, but especially in the Convent of San Jerónimo. Of every ten sick nuns, nine died. On February 17, Núñez de Miranda died. Sor Juana falls ill a short time later, because she collaborated taking care of the sick nuns. She passes away at four in the morning on April 17. According to one document, she left behind 180 volumes of selected works, furniture, an image of the Holy Trinity, and a Baby Jesus. Everything was delivered to her family, with the exception of the images, which she herself, before passing away, had left to the archbishop. She was buried the day of her death, with the assistance of the cathedral chapter. Her funeral was presided over by Canon Francisco de Aguilar and the funeral prayer was performed by Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora. On her tombstone was placed the following inscription:

In this enclosure that is the low and burial choir of the nuns of San Jerónimo was buried Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz on April 17, 1695.

In 1978, during routine excavations in the center of Mexico City, his alleged remains were found, to which great publicity was given. Several events were held around the discovery, although its authenticity could never be confirmed. Currently, they are located in the Historic Center of Mexico City, between the streets of Isabel la Católica and Izazaga.

Characteristics of his work

He composed a wide variety of plays. His most famous comedy is Los empeños de una casa , which in some of its scenes is reminiscent of the work of Lope de Vega. Another of her well-known plays is Love Is More Labyrinth, where she was esteemed for creating characters of hers, such as Theseus, the main hero. His three sacramental plays reveal the theological side of his work: The martyr of the sacrament —where he mythologizes Saint Hermenegildo—, The scepter of Joseph and The divine Narcissus, written to be represented in the court of Madrid.

His lyrics also stand out, which approximately accounts for half of his production; love poems in which disappointment is a popular resource, lobby poems and occasional compositions in honor of characters of the time. Other outstanding works by him are his carols and the tocotín, a kind of derivation of that genre that intersperses passages in native languages. She also wrote a treatise on music called El caracol , which has not been found, however, she considered it a bad work and it may be that because of this she would not have allowed its dissemination.

According to her, almost everything she had written was commissioned and the only thing she wrote for her own pleasure was First Dream. Commissioned by the Countess of Paredes, he produced some poems that tested the ingenuity of his readers —known as "enigmas"— for a group of Portuguese nuns who were fond of reading and great admirers of his work, who exchanged letters and formed a society to which they gave the name Pleasure House. The handwritten copies made by these nuns of Sor Juana's work were discovered in 1968 by Enrique Martínez López in the Lisbon Library.

Themes

In the field of comedy, it starts above all from the meticulous development of a complex intrigue, an intelligent entanglement, based on mistakes, misunderstandings, and twists and turns that, nevertheless, are solved as a reward for the virtue of the actors. protagonists. He insists on addressing the private problems of families (Los empeños de una casa), whose precedents in Spanish baroque theater range from Guillén de Castro to Calderonian comedies such as La dama duende, Casa con dos puertas mala es de guardar and other works that address the same theme as Los empeños.

One of his great themes is the analysis of true love and the integrity of value and virtue, all reflected in one of his masterpieces, Love is more of a labyrinth. He also highlights (and is exemplified by all his works) the treatment of women as a strong character who is capable of handling the wills of the surrounding characters and the threads of their own destiny.

It is also observed, confessed by herself, a permanent imitation of the poetry of Luis de Góngora and his Soledades, although in a different atmosphere from his, known as Apolo Andalusian. The environment in Sor Juana is always seen as nocturnal, dreamlike, and at times even complex and difficult. In this sense, First I dream and all her lyrical work, address the vast majority of the forms of expression, classical forms and ideals that can be seen in all the lyrical production of the nun of San Jerónimo.

In his Athenagorical Letter, he refutes point by point what he considered erroneous thesis of the Jesuit Vieira. In keeping with the spirit of the thinkers of the Golden Age, especially Francisco Suárez. He draws attention to his use of syllogisms and casuistry, used in an energetic and precise prose, but at the same time as eloquent as in the first classics of the Spanish Golden Age.

In view of the recrimination made by the Bishop of Puebla as a result of his criticism of Vieira, he did not refrain from answering the hierarch. In the Response to Sor Filotea de la Cruz one can guess the freedom of the criteria of the poetess nun, her sharpness and her obsession with achieving a personal, dynamic style without impositions.

Style

The predominant style of his works is baroque; Sor Juana was very given to making puns, verbalizing nouns and substantivizing verbs, accumulating three adjectives on the same noun and distributing them throughout the sentence, and other grammatical liberties that were in fashion at her time. She is also a teacher in the art of the sonnet and in the baroque concept.

His lyrics, witness to the end of the Hispanic Baroque, have within reach all the resources that the great poets of the Golden Age used in their compositions. In order to give his poetry an air of renewal, he introduces some technical innovations and gives it his very particular stamp. Sor Juana's poetry has three main pillars: versification, mythological allusions and hyperbaton.

Several scholars, especially Tomás Navarro Tomás, have concluded that she achieves an innovative mastery of verse reminiscent of Lope de Vega or Quevedo. The perfection of her metric entails, however, a problem of chronology: it is not possible to determine which poems were written first on the basis of stylistic issues. In the field of poetry, Sor Juana also turned to mythology as a source, as well as than many Renaissance and Baroque poets. The deep knowledge that the writer had of some myths causes some of her poems to be flooded with references to these topics. In some of her most cult-like compositions, this aspect is more noticeable, since mythology was one of the paths that every scholarly poet, in the style of Góngora, had to show.

On the other hand, the hipérbaton, a resource that has been helped in the time, reaches its splendor in The dream, work full of forced syntax and of combination formulations. Rosa Perelmuter points out that in New Spain the nun of San Jerónimo was the one who brought Baroque literature to the summit. The sorjuanese work is a characteristic expression of Baroque ideology: it poses existential problems with a manifestly allocating intention, the topicals are well known and are part of the Baroque «disengine». In addition, elements such as the carpe diemthe triumph of reason against the physical beauty and the intellectual limitation of the human being.

Sor Juana's prose is made up of independent and short sentences separated by punctuation marks —comma, period and semicolon— and not by subordination links. Therefore, juxtaposition and coordination predominate. The scarce presence of subordinate clauses in complex periods, far from facilitating understanding, makes it arduous, it is necessary to replace the logic of the relationships between the sentences, deducing it from the meaning, from the idea being expressed, which is not always easy. Its depth, then, is in the concept as well as in the syntax.

Fonts

He stands out for his ability to cultivate both the comedy of entanglements (Los empeños de una casa) and the sacramental plays. However, his works hardly touch themes of the popular ballads, limiting themselves to comedy and mythological or religious matters. His emulation of outstanding authors of the Golden Age is well known. One of his poems presents the Virgin as Don Quixote de la Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes, saving people in trouble. His admiration for Góngora is manifested in most of his sonnets and, above all, in Primero sueño, while the enormous influence of Calderón de la Barca can be summed up in the titles of two Sorjuanesque works: The Pawns of a House, an emulation of The Pawns of a Sunset, and The Divine Narcissus, a title similar to The Divine Orpheus from Calderón.

Her training and desires are those of a theologian, like Calderón, or a friar, like Tirso, or a specialist in sacred history, like Lope de Vega. The sacred conception of her dramaturgy led her to defend the indigenous world, to which she appealed through her sacramental autos.She takes her affairs from very diverse sources: from Greek mythology, from legends pre-Hispanic religions and the Bible. She has also pointed out the importance of observing contemporary customs, present in her works such as Los empeños de una casa .

Characters

Most of its characters belong to mythology, and there are few bourgeois or farmers. This moves away from the moralizing intention in line with the didactic assumptions of religious tragedy. In his work, the psychological characterization of the female characters stands out, often protagonists, always intelligent and finally capable of leading their destiny, despite the difficulties with which the condition of women in the structure of baroque society weighs down their possibilities of acting and decision. Ezequiel A. Chávez, in his Psychology Essay, points out that in his dramatic production the male characters are characterized by their strength, even reaching extremes of brutality; while women, who begin by personifying the qualities of beauty and the ability to love and be loved, end up being examples of virtue, firmness and courage.

Sor Juana's sacramental plays, especially José's Scepter, include a large number of real characters —José and his brothers— and imaginary ones, such as the personifications of various virtues. The patriarch Joseph appears as the foreshadowing of Christ in Egypt. The allegorized passage of the car, where the transposition of the Biblical story of Joseph takes place, makes it possible to equate the dreams of the Biblical hero with the knowledge given by God.

Feminist reading

From modern critical perspectives, the figure and work of Sor Juana are framed within feminism.

Academic Dorothy Schons who recovers in the mid-20s and 30s of the 20th century in the US the forgotten figure of Sor Juana considers her "the first feminist in the New World".

Two texts stand out in particular: Response to Sor Filotea de la Cruz where she defends the right of women to education and access to knowledge and the roundup Fool Men, where he questions the masculine hypocrisy of the time.

For the Mexican academic Antonio Alatorre, the satirical roundup in question lacks feminist traces and offers, rather, a moral attack pointing out the hypocrisy of seductive men, whose precedents can be found in authors such as Juan Ruiz de Alarcón: it was not nothing new to attack the moral hypocrisy of men with respect to women. The Response only limits itself to demanding the right to education for women, but restricting itself to the customs of the time. It is a direct criticism and a personal defense, to his right to know, to knowledge, to the natural inclination for knowledge that God gave him.

An author who denies feminism in said work is Stephanie Marrim, who points out that one cannot speak of feminism in the nun's work, since she only limited herself to defending herself: the feminist allusions in her work are strictly personal, not collective. According to Alatorre, Sor Juana decided to neutralize her sexuality symbolically through the nun's habit. About the marriage and her entry into the convent, the Response states:

Although I knew that I had the state things [...] many repugnant to my genius, with everything, for the total denial that I had to marriage, was the least disproportionate and the most decent thing I could choose in matters of the security that I wanted from my salvation.

According to most philologists, Sor Juana advocated for the equality of the sexes and for the right of women to acquire knowledge. Alatorre recognizes it: "Sor Juana, the indisputable pioneer (at least in the Spanish-speaking world) of the modern women's liberation movement." Along the same lines, the scholar Rosa Perelmuter analyzes various features of Sor Juana's poetry: the defense of of women, their personal experiences and a relative rejection by men. Perelmuter concludes that Sor Juana always privileged the use of the neutral voice in her poetry, in order to achieve a better reception and criticism.

According to Patricia Saldarriaga, First Dream, Sor Juana's most famous lyrical work, includes allusions to female bodily fluids such as menstruation or lactation. In medieval literary tradition the menstrual flow was believed to nourish the fetus and then become breast milk; This situation is used by the poetess to emphasize the extremely important role of women in the cycle of life, creating a symbiosis that allows the process to be identified with a divine gift.

Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo and Octavio Paz consider that Sor Juana's work breaks with all the canons of women's literature. She defies knowledge, immerses herself completely in epistemological questions alien to women of that time, and often writes in scientific, not religious, terms. According to Electa Arenal, all of Sor Juana's production —especially El sueño and various sonnets—reflect the poet's intention to create a universe, at least literary, where women reigned above all things. The philosophical nature of these works gives the nun the invaluable opportunity to discuss the role of women, but sticking to their social reality and their historical moment.

Works

Dramatic

In addition to the two comedies reviewed here (Los empeños de una casa and Amor es más laberinto, written together with Juan de Guevara), Sor Juana has been attributed the authorship of a possible ending to Agustín de Salazar's comedy: La Segunda Celestina. In the 1990s, Guillermo Schmidhuber found a release that contained a different ending than the one known and proposed that those thousand lines were from Sor Juana. Some Sor Juana members have accepted Sor Juana's co-authorship, including Octavio Paz, Georgina Sabat-Rivers, and Luis Leal. Others, such as Antonio Alatorre and José Pascual Buxó, have refuted it.

The second Celestina

This comedy was written to be performed on the birthday of Queen Mariana of Habsburg (December 22, 1675), but its author Agustín de Salazar y Torres died on November 29 of the same year, leaving the comedy unfinished. In 1989 Schmidhuber presented the hypothesis that an ending until then considered anonymous to Salazar's comedy, which had been published in a single with the title "La segunda Celestina", could be the work of Sor Juana. The comedy was published in 1990 by Octavio Paz, with a prologue of his assigning the authorship to Sor Juana. In New Spain there is news of a performance of this piece at the Coliseo de Comedias in 1679, as quoted by Armando de María y Campos. In 2016 this comedy was performed at the National Palace by the Classic Theater Company, under the direction by Francisco Hernandez Ramos. The comedy has been published several times, the edition of the University of Guadalajara and the Instituto Mexiquense de Cultura of the State of Mexico stand out.

The pawns of a house

It was performed for the first time on October 4, 1683, during the celebrations for the birth of the viceroy Count of Paredes' eldest son. However, some critics maintain that it could have been staged for the entrance to the capital of the Archbishop Francisco de Aguiar y Seijas, although this theory is not considered entirely viable.

The story revolves around two couples who love each other, but, by chance, cannot be together yet. This comedy of entanglements is one of the most outstanding works of late-baroque Spanish-American literature and one of its most peculiar characteristics is the woman as the central axis of the story: a strong and determined character who expresses the desires -often frustrated- of the nun. Doña Leonor, the protagonist, fits perfectly into this archetype.

It is often considered the pinnacle of Sor Juana's work and even of all New Spanish literature. The handling of intrigue, the representation of the complicated system of conjugal relations and the vicissitudes of urban life make Los empeños de una casa an unusual work within the theater in colonial Spanish America.

Love is more of a labyrinth

It was premiered on February 11, 1689, during the celebrations for Gaspar de la Cerda y Mendoza's assumption of the viceroyalty. It was written in collaboration with Fray Juan de Guevara, a friend of the poetess, who only wrote the second day of the theatrical celebration. Fernández del Castillo as co-author of this comedy.

The plot takes up a well-known theme from Greek mythology: Theseus, a hero from the island of Crete, fights against the Minotaur and awakens the love of Ariadne and Phaedra. Theseus is conceived by Sor Juana as the archetype of the baroque hero, a model also used by his compatriot Juan Ruiz de Alarcón. By triumphing over the Minotaur, he does not become arrogant, but recognizes his humility.

Sacramental Cars

From the end of the 18th century to the middle of the 19th century, the genre of the auto sacramental was almost forgotten. The prohibition to represent them in 1765 led critics to point it out as a distortion of taste and an attack against the principles of Catholicism. German romanticism is responsible for the revaluation of the auto sacramental and the interest in studying the subject, which led to pointing out its importance in the history of Spanish literature.

In New Spain, the auto sacramental began to be represented immediately after the Conquest, as it was a useful means to achieve the evangelization of the indigenous people. Sor Juana wrote three autos commissioned by the court of Madrid —El divino Narciso, El cetro de José and El mártir del sacramento— whose themes They address the European colonization of America. Here Sor Juana takes resources from the theater of Pedro Calderón de la Barca and uses them to create lyrical passages of great beauty.

The Divine Narcissus

It is the most well-known, original and perfect of Sor Juana's auto sacramentales. It was published in 1689. El divino Narciso represents the culmination of the auto sacramental tradition, brought to its point higher by Pedro Calderón de la Barca, from whom Sor Juana takes most of the elements of the car, and takes them even further creating a great sacramental car. In El divino Narciso Sor Juana uses a set lyrical-dramatic to give life to the characters created. The divine Narcissus, personification of Jesus Christ, lives in love with his image, and the whole story is narrated from that point of view. Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo, Julio Jiménez Rueda and Amado Nervo have agreed that El divino Narciso is the most successful of Sor Juana's plays.

It alludes to the theme of the conquest of America and the traditions of the native peoples of the continent, although this theme was not popular in the literature of its time. Sor Juana takes advantage of an Aztec rite, represented by a tocotín, in honor of Huitzilopochtli to introduce the veneration of the Eucharist and link pre-Columbian beliefs with Hispanic Catholicism. It is one of the pioneering works in representing the collective conversion to Christianity, since the European theater was used to representing only individual conversion.

The work features the participation of allegorical characters based mainly on Greco-Roman mythology, and to a lesser extent on the Bible. Human Nature, the protagonist, dialogues with Synagogue and Kindness, and confronts Eco and Pride. At the same time, Narcissus, the divine shepherd son of the nymph Liríope and the river Cefiso, personifies Christ.

El divino Narciso is in many ways more than Calderonian theater, since its reflection encompasses the relationship between two worlds. Of the various possible sources of the conception of Narcissus as Christ may be mentioned from Plotinus to Marsilio Ficino. The theological and metaphysical dimension of the work also refers to the texts of Nicolás de Cusa, whose philosophy inspires many of Sor Juana's best pages. In El divino Narciso, the meaning of the theatrical exposition of the New Spanish author on the sacrament of the Eucharist can be traced from apologetic literature. Considering that the loa governs a subtle line of argument about how pagan gods are reverberations of Christian truth, be it in the Old or in the New World, we can find various mythical parallels in the car that express different facets of the Christian religion under the principles offered by the apologists who catechized the ancient world. The echo of the apologetic literature of the beginning of the Christian era reverberates, then, in this work by Sor Juana to the extent that in it there are multiple glimpses of the ancient pagan gods as unfinished or imperfect versions of the history of Christ. The delicacy of the verses, the strophic variety and the dramatic and plot resolution also make El divino Narciso one of the most perfect works of New Spanish literature. Her proposal —in addition to being pacifist through a host of Orphic-Pythagorean references— also fulfills the mission of the order to syncretize the ancient Mexica religion in favor of Christianity and offers the reader a poetic and ecumenical thesis of the Christian religion..

Joseph's Scepter

The date of its composition is unknown, but it was published, along with El mártir del sacramento in the second volume of Inundación castálida in 1692 in Madrid. that El divino Narciso, José's scepter uses pre-Columbian America as a vehicle to tell a story with biblical and mythological overtones. The theme of human sacrifices appears again in Sor Juana's work, as a diabolical imitation of the Eucharist. Even so, Sor Juana feels affection and appreciation for the indigenous people and for the missionary friars who brought Christianity to America, as can be seen in several car sections. In addition, the car is a pioneer in representing collective conversions to Christianity, something unusual until then in religious literature.

Joseph's scepter belongs to the Old Testament records, and is the only one of its kind composed by Sor Juana. Calderón de la Barca wrote several Old Testament autos, of which Sueños hay que verdad son stands out, also inspired by the figure of the patriarch José. It is customary to consider that Sor Juana wrote her autos with the firm conviction, encouraged by the Countess of Paredes, that they would be performed in Madrid. For this reason, the themes and style of these works were directed towards the peninsular public, although there is no written record that they were staged outside of New Spain.

The martyr of the sacrament

It addresses the issue of the martyrdom of Saint Hermenegildo, a Visigothic prince, son of Leovigildo, who died for refusing to worship an Arian host. It could be classified as self-allegorical-historical, like The Great House of Austria, by Agustín Moreto, or El santo rey don Fernando, by Calderón de la Barca. The language is very flat and simple, except for some academic technicalities. It is a costumbrista work, in the style of the hors d'oeuvres of the 16th century and of some Calderonian works. Sor Juana deals with a subject that is, at the same time, hagiographic and historical. On the one hand, she tries to strengthen the figure of San Hermenegildo as a model of Christian virtues; on the other, its source is the great General History of Spain, by Juan de Mariana, the most renowned work of that time. The author plays with "El General", a kind of auditorium of the Colegio de San Ildefonso, and with the company of actors who will represent his car. The play begins when the first carriage is opened, and there are two more in the rest of the staging.

Lyrical

Love poetry

In some of her sonnets, Sor Juana offers a Manichean vision of love: she personifies the loved one as virtuous and the hated lover she grants all the defects. Several of her critics have wanted to see in it a frustrated love of her time at her court, although it is not a thesis supported by the community of scholars. Paz, for example, points out that if her work had reflected any love trauma, it would have been discovered and would have caused a scandal.

Sor Juana's love poetry embraces the long tradition of medieval models set in the Spanish Renaissance, which evolved seamlessly into the Baroque. Thus, in its production you can find the typical Petrarchan antitheses, the laments and complaints of courtly love, the Neoplatonic tradition of León Hebreo and Baltasar Castiglione or the baroque neostoicism of Quevedo.

It can be classified into three groups of poems: friendship, of a personal nature, and love affairs. In Sor Juana's lyrical work, for the first time, the woman ceases to be the passive element of the love relationship and recovers her right, which the poetess considered usurped, to express the varied range of love situations.

The so-called friendship or courtly poems are devoted, in the vast majority of cases, to extolling Sor Juana's great friend and patron: the Marquise de la Laguna, whom she nicknamed "Lisi&# 3. 4;. They are poems of a Neoplatonic nature, where love is stripped of all sexual ties to affirm itself in a brotherhood of souls on a spiritual level. On the other hand, the idealization of the woman that Neoplatonism takes from medieval courtly love is present in these poems in continuous praise of the beauty of the marquise.

In the other two groups of poems, a varied series of love situations is analyzed: some very personal, a legacy of Petrarchism prevailing at the time. In a good part of her poems, Sor Juana confronts passion, an intimate impulse that should not be rejected, and reason, which for Sor Juana represents the pure and disinterested aspect of true love.

First dream

It is his most important poem, according to critics. According to the poet's testimony, it was the only work that she wrote for pleasure. It was published in 1692. It appeared edited under the title First Dream. Since the degree is not the work of Sor Juana, a good part of the critics doubts the authenticity of its accuracy. In the Response to Sor Filotea de la Cruz Sor Juana referred only to the Dream. However it may be, and as the poet herself stated, the title of the work is a tribute to Góngora and her two Soledades.

It is the longest of Sor Juana's poems —975 verses— and its theme is simple, although presented with great complexity. This is a recurring theme in Sor Juana's work: the intellectual potential of the human being. To transform this theme into poetry, he resorts to two literary resources: the soul leaves the body, to which he gives a dreamlike framework.

The literary sources of the First Dream are diverse: the Somnium Scipionis, by Cicero; The madness of Hercules, by Seneca; the poem by Francisco de Trillo y Figueroa, Painting of the night from one twilight to another; the Itinerary to God, of San Buenaventura and several hermetic works by Atanasio Kircher, in addition to the works of Góngora, mainly the Polifemo and the Soledades, from where it takes the language with which it is written.

The poem begins with the nightfall of the human being and the dream of nature and man. Then the physiological functions of the human being and the failure of the soul when attempting a universal intuition are described. Given this, the soul resorts to the deductive method and Sor Juana alludes excessively to the knowledge that humanity possesses. She remains yearning for knowledge, although she acknowledges the limited human capacity to understand creation. The final part tells of the awakening of the senses and the triumph of day over night.

It is the work that best reflects Sor Juana's character: passionate about the sciences and the humanities, a heterodox trait that could presage the Enlightenment. Paz's judgment on the First Dream is blunt: «Sor Juana's absolute originality must be underlined, as far as the matter and the substance of her poem are concerned: there is nothing in all Spanish literature and poetry of the 16th and 17th centuries that resembles the First dream ".

The “First dream”, as Octavio Paz points out, is a unique poem in the poetry of the Golden Age, since it unites poetry and thought in its most complex, subtle and philosophical expressions, something not frequent in its time. He draws on the best mystical and contemplative tradition of his time to tell the reader that man, despite his many limitations, has within himself the spark (the "flash", according to Sor Juana) of the intellect, which participates in divinity. This tradition of Christian thought (the Patristics, Pseudo Dionysius the Areopagite, Nicholas of Cusa, etc.) considers the night as the ideal space for the soul to approach divinity. The nocturnal birds, as attributes of the goddess Minerva, associated with the triform moon (because of its three visible faces) and a symbol of circumspect wisdom, symbolize wisdom as an attribute of the night (In nocte consilium), one of the most dear themes to humanist thought, present in Erasmus of Rotterdam and in a whole group of exponents of this idea in the Renaissance and the Baroque. That is why nocturnal birds are the symbols that preside over what it will be the dream of the soul in search of knowledge of the world created by divinity. This explains why night appears in Sor Juana's poem as a synonym for Harpocrates, the god of prudent silence, who, as an aspect of night, tacitly accompanies the trajectory of the soul's dream until the end. The night, therefore, is an ally and not an enemy, since it is the space that will give rise to the revelation of the dream of the soul. The figures of the deer (Actaeon), the lion and the eagle appear, first, as the daytime animals that are opposed to the nocturnal birds to represent the act of vigilant sleep. In other words, they represent the idea that Sor Juana is interested in highlighting: rest should not be completely absent from intellectual consciousness, but rather be a vigilant and attentive sleep the revelations of divine wisdom. These daytime animals also symbolize the three most important exterior senses: sight, hearing and smell, which remain inactive during sleep. Thus, the nocturnal birds are harmoniously linked in their wise vigil, daytime animals in their vigilant sleep, and the human being, whose body (corporal members and external senses) physically sleeps while his soul, conscious, is temporarily released to embark on the adventure of co knowledge, which occurs in two ways: the intuitive and the rational. In the first, the soul is fascinated by the instantaneous contemplation of the totality of creation, but is unable to form a concept of that fleetingly contemplated totality. In the rational way, the soul recovers the use of its reasoning faculty after being dazzled by the sun, but finds the human method (which is the Aristotelian method of the ten categories) ineffective to understand the countless mysteries of creation. In both ways the soul fails in its attempt, which, however, is always renewed. Only awakening seems to give a truce to this dream of the desire for knowledge that always tends to reach the mystery of God, of the nature that he created and of man himself as the "locking hinge" between God and the created world.

Intuition

The first way to try to access that “First Cause” of which Sor Juana speaks (“And to the First Cause she always aspires”) is that in which the totality of things are presented “in a single glance". This communion of things must appear in the dream, once one is inside it, because, as we will see in the section dedicated to the dream as a place of fantasy, the dream is the place where The content that is kept in memory, which is the raw material with which the understanding will have to flow, can be freed from the demands of the body, as Sor Juana points out: «The soul, then, suspends / from the external government —in that, busy/ in material employment,/ or good or bad— counts the day as spent».

Through intuition, particular things are still unknown to us, so we could not say that we fully know, because within that full knowledge, would be the knowledge of the very essences of things: " She herself recognized the insufficiency of an intuition that tried to cover all things, without getting to know the intimate essence of each one. The path that she has to follow is precisely the opposite: start with particular things, to later rise to the total vision & # 34;.

Sor Juana was looking for a complete knowledge of things, so once she noticed the insufficiency of the path of intuition for her purpose, she would have to draw up a new method, rather, retake the Aristotelian project (later scholastic), of Starting from ten categories in which the totality of things must be thought, ascending more and more, from the lowest to the highest, he says:

“more thought convenient/to the singular matter to be reduced,/or separately/ one by a passage of things/ that come to be girded/ in which, artifices,/ twice five are Categories:/ metaphysical reduction that teaches/ (the ents conceiving sweet generals/ in only a few fantasies/ where matter is detached/ the discourse abstracted)/

Sor Juana begins to follow the Aristotelian method of starting from things themselves to rise, through understanding, towards the First Cause.

Fantasy from Aristotle's De Anima

The material with which understanding operates is not the things themselves, they are something else that allows us to store images in our memory that are recorded in us.

The Aristotelian operation starts from this raw material, which is what we have from objects, so that abstraction only operates on ourselves, nothing guarantees that from this knowledge we can access a higher one.

Ioan P. Couliano, an author recognized for his work: "Eros and magic in the Renaissance" tells us the following: “Aristotle does not question the existence of the Platonic dichotomy between body and soul. However, studying the secrets of nature, he feels the need to empirically define the relationships between these two isolated entities, whose almost impossible union from the metaphysical point of view constitutes one of the deepest mysteries of the universe.

In book 3 of De Anima, Aristotle notes that between the soul and the body, there must be an intermediate that communicates them, he says: “Imagining is, therefore, giving an opinion about the sensitive object perceived not accidentally. Now then, certain sensible objects produce a false image to the senses and, nevertheless, are judged according to the truth". image: is that images are like sensations only without matter. Imagination is, moreover, something different from affirmation and negation, since truth and falsehood consist of a composition of concepts... Wouldn't it be possible to say that neither these nor the other concepts are images, although they are never images? do they give no pictures?”

This is where Culianu's interpretation of fantasy will come from and how these ghosts (or images according to the translation) are protected within the memory and they are operated in the understanding, he says:

“In short, the soul can only transmit to the body all vital activities, as well as mobility, through the proton organon, the pneumatic apparatus located in the heart. On the other hand, the body opens a window to the soul to the world through the five sense organs, whose messages reach the same cardiac device, which then deals with encoding them so that they are understandable. Under the name of phantasia, or internal sense, the sidereal spirit transforms the messages of the five senses into phantoms perceptible by the soul. This is so because it cannot capture anything that is not converted into a sequence of ghosts; in short, it cannot understand anything without ghosts (aneu plzantasmatos)”.

Others

A good part of Sor Juana's lyrical work is made up of situation poems, created for social events where the hosts were praised excessively. They are festive poems, where many trivial situations were magnified. To a certain extent, they are a faithful reflection of a society consolidated on two very strong pillars: the Church and the Court.

In them, Sor Juana uses the most varied poetic resources that she has learned throughout her life: the surprising image, the lexical cultism, the omnipresent religious allusion, the game of concepts, syntactic resources that remind Góngora and personal references that they serve as a counterbalance to the inordinate praise that most of them contain.

He also wrote humorous and satirical poetry. The mockery of oneself was not new to baroque rhetoric, a current in which Sor Juana participates by writing a wide range of mocking poems. Her satire on "foolish men" is the best known of her poems. Paz points out:

The poem was a historical rupture and a beginning, for the first time in the history of our literature a woman speaks in her own name, defends her sex and, thanks to her intelligence, using the same weapons as her detractors, accuses men of the same vices that they reject women. In this Sor Juana advances his time: there is nothing like it, in the seventeenth century, in the female literature of France, Italy and England.Peace, Octavian. Sr. Juana Inés de la Cruz or the traps of faith. Mexico: FCE, 1982, pp. 399-400.

During her life, Sor Juana composed sixteen religious poems, an extraordinarily small number, which is surprising given the little interest the nun had in religious matters. Most of them are occasional works, but there are three sonnets in which the poetess presents the relationship of the soul with God in more human and loving terms.

Prose

Allegorical Neptune

It was written to commemorate the entry of the viceroy Marquis de la Laguna into the capital on November 30, 1680. At the same time, Sor Juana published a very long poem as an explanation of the arch. It consists of three main parts: the "Dedication", "Reason for the factory" and "Explanation of the arch".

In the canvases and statues of this triumphal arch, the virtues of the new viceroy were represented, personified by the figure of Neptune. The work belongs to a very long classical tradition that links the benefits of heroes or rulers with triumphal arches and a specific allegorical context. Although the marquis is linked only to the god of the sea, his divinization encompasses all the natural kingdoms. It was very well received in New Spain society, both by the incoming viceroys and by a large part of the clergy.

For Paz, the work, in addition to being influenced by Atanasio Kircher, establishes a connection between the religious veneration of ancient Egypt and the Christianity of the time. This work was also the cause of the obfuscation of Antonio Núñez de Miranda, confessor and friend of the poetess. Several authors conjecture that the prelate was jealous of the prestige that her friend was acquiring at court, while hers was declining, which broke their relationship. Shortly after, feeling supported by the viceroys, Sor Juana allowed herself to dismiss him as confessor.

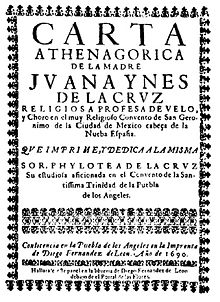

Athenagorical letter

It was published in November 1690, in Puebla de Zaragoza, by Bishop Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz. Atenagorica means "worthy of the wisdom of Athena". The letter is a criticism of Portuguese António Vieira's Mandato sermon on the finesse of Christ.

It marks the beginning of the end of Sor Juana's literary production. A short time later, in 1693, Sor Juana will undertake a series of little works called superogacion, in which she intended to thank God for the many favors received.

Through her main conclusions, Sor Juana maintains that dogmas and doctrines are the product of human interpretation, which is never infallible. As in the vast majority of her texts, both dramatic and philosophical, the interpretation of theological topics becomes a conceptualist game full of ingenuity.

In March 1691, as a continuation of this letter, Sor Juana wrote the Response to Sor Filotea de la Cruz, where she defended herself arguing that the vast knowledge she possesses in various areas is sufficient so that he is allowed to discuss theological issues that should not be confined solely to men.

It is one of Sor Juana's most difficult texts. It was originally titled Crisis de un sermón, but when it was published in 1690 Fernández de Santa Cruz gave it the name Carta atenagórica. For Elías Trabulse, the true addressee of the Athenagorical Letter is Núñez de Miranda, who celebrates in his sermons and writings the theme of the Eucharist, central to the Letter, although Antonio Alatorre and Martha Lilia Tenorio have refuted this hypothesis.

Following a hypothesis formulated by Darío Puccini and expanded by Octavio Paz Schuller thinks that, even if it was addressed to Núñez, it is not improbable that Aguiar felt attacked by the publication. According to Paz and Puccini's hypothesis, Santa Cruz circulated the letter among the theological community of the viceroyalty, in order to reduce the archbishop's influence. The admiration that the Bishop of Puebla felt for Sor Juana is well known, which led him to forget the misogynistic attitude that prevailed in the 17th century.

One of the questions that Paz asks is who is being criticized in the Athenagorical Letter. Between 1680 and 1681 there was a dilemma in Madrid for the election of the very important post of Archbishop of Mexico, after Fray Payo Enríquez de Rivera left. Fernández de Santa Cruz was one of the options considered, along with Francisco de Aguiar y Seijas. This was a faithful admirer of Vieira. By attacking Vieira in a sermon written 40 years earlier, Sor Juana became involved in a dispute for power between the two clerics, challenging Aguiar and Seijas—known for being misogynistic, for censoring theater, poetry, and comedy. The Carta Atenagorica is published by the Puebla prelate under the pseudonym Sor Filotea de la Cruz, with a prologue in which he praises and criticizes the nun for her attributions to sacred letters.

Faced with this hypothesis, Antonio Alatorre and Martha Lilia Tenorio believe that in one of the many gatherings that Sor Juana held, there was talk of Vieyra's Sermón del Mandato, and Sor Juana's interlocutor, listening to her, asked her to put her opinions in writing. This interlocutor of Sor Juana, whoever he may be, decided to make copies of Sor Juana's writing, and one of them reached the hands of the Bishop of Puebla, who published it under the name Carta Athenagórica. This is in contrast to the elaborate conspiracy hypotheses that are very popular among Sor Juanistas, as they point out.

With the above we mean that, as well as the romance of jealousy was the result of a conversation with the Countess of Paredes about poetry, Crisis It was a conversation with a certain visitor of San Jerónimo, perhaps Brother Antonio Gutiérrez (and if not him, any other theologian's knowledge). Sor Juana liked the orders so much, that he disguised them as “precepts”, so that compliance was “obedience”. What he says in the Response a Sor Filotea on the genesis of the Crisis Couldn't be clearer. But in recent times, as the reader will see in several places of this book, it has become fashionable to programmatically doubt the sincerity of Sor Juana and, worse still, discover after his words all kinds of second intentions, cunning calculations and complicated intrigues. We feel that these conjectures are idle and unnecessary. The genesis of the Crisis is like the genesis of almost everything that Sor Juana wrote. We don't see any mystery.Antonio Alatorre and Martha Lilia Tenorio, Serafina and Sor Juana. Mexico: The College of Mexico, 1998, p. 16

Response to Sor Filotea de la Cruz

It was written in March 1691, as a response to all the recriminations made by Fernández de Santa Cruz, under the pseudonym Sor Filotea de la Cruz. The bishop warns that no woman should have struggled to learn about certain philosophical topics. In her defense, Sor Juana points to several learned women, such as Hypatia, a Neoplatonic philosopher assassinated by Christians in the year 415. She writes about her failed attempt and the constant pain that her passion for knowledge brought her, but exposing a conformism, already which clarifies that it is better to have a vice to letters than to something worse. She also justifies the vast knowledge she has of all educational subjects: logic, rhetoric, physics, and history, as a necessary complement to understanding and learning from the Holy Scriptures.

The Sor Filotea's Letter expresses the admiration that the Bishop of Puebla feels for Sor Juana, but reproaches him for not using his enormous talent in profane matters, but in divine themes. Although he does not declare himself against the education of women, he does express his disagreement with the lack of obedience that some already educated women could show. Finally, he recommends that the nun follow the example of other mystical writers who dedicated themselves to theological literature, such as Saint Teresa of Jesus or Gregorio Nacianceno.

Sor Juana agrees with Sor Filotea that she must show obedience and that nothing justifies the prohibition to write verses, at the same time that she affirms that she has not written much about Scripture because she does not consider herself worthy of doing so. She also challenges Sister Filotea and all her enemies to present her with a song of hers that is indecent. Hers cannot be described as lascivious or erotic poetry, which is why many critics consider that the affection she showed for the viceroys was filial, not carnal.

Protest of faith

Protest of the faith and renewal of the religious vows that mother Juana Inés de la Cruz, a professed nun in San Gerónimo de México, made and left written with her blood, is a work from 1695 in in which Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz reaffirms her faith in Christ, in which she urges to love him above all things and even shed every last drop of blood for him. In this work she reflects the importance of fervor for Jesus Christ in her life.

Praise

Sor Juana published twelve praises, nine of which appeared in the Inundación castálida and the rest in volume II of her works. Three Sorjuanesque loas preceded, as a prologue, their sacramental proceedings, although all of them have their own literary identity. Works with a cult tone, around 500 verses, included praises to the characters of the time - to Carlos II and his family dedicated six loas, two to the viceregal family and one to Father Diego Velázquez de la Cadena. They used to be represented with all lavishness and had an excessively flattering tone and artificial themes, as required by the cultured poetics of the 17th century. Most of Sor Juana's praises, mainly those of a religious nature, are compositions in a flowery and conceptual style, with great variety of metrical forms and firm clarity of thought. In this aspect, the Loa of the Conception stands out.

Five praises were composed "to the years of King Carlos II", that is, for his birthdays. In each of them Sor Juana celebrates the Spanish empire in tenths of vivacious rhythmic and quadratic splendor. Even so, the second loa of this class presents a flat style, a long romance and a certain strophic sobriety. Another of the loas, simpler, makes many mythological allusions of enormous acuity to celebrate November 6, the date of the king's birth. The rest of these loas, of enormous decorative display, celebrate Carlos using fabulous allegories, lyrical pieces of exceptional musicality and color. These praises are representative work of the very baroque style of Sor Juana.

He also wrote a praise to the queen consort, María Luisa de Orleans, full of sharp puns and a Calderonian imprint that stands out above all in the metaphors. Another of the praises was dedicated to the queen mother, Mariana of Austria. It is a composition very similar to those written in honor of Carlos II, although with less majesty. The decasyllables of esdrújulo start and the mythological allegory to extol the queen stand out in it.

He also dedicated several praises to his friends and protectors, the Marquises of La Laguna and the Counts of Gelve. Once again, she uses mythological resources to sing of the virtues of her rulers. What enhances her style is the agility to create symbols and similes, through a very Calderonian game woven by the anagrams or initials of the characters that Sor Juana intends to ponder..

Carols

Sor Juana's villancicos, unlike her loas, are simple and popular compositions that were sung at matins of religious festivals. Each set of carols obeys a fixed format of nine compositions—eight sometimes, since the latter was easily substitutable for the Te Deum—, which gave them considerable length.

Thematically, Christmas carols celebrate some religious event in a wide range of poetic tones ranging from the cult to the popular. Although the Christmas carols often included compositions in Latin, the truth is that the whole piece veered towards the popular, in order to attract the attention of the people and generate joy. Sor Juana, like other Baroque creators, has full command of popular poetry and her carols are proof of this, as she managed to capture and transmit the joyful comedy and simple tastes of the people. Sung at matins, the carols have a clear dramatic configuration, thanks to the different characters involved in them.

In Los villancicos al glorioso San Pedro Sor Juana presents the apostle as a champion of true justice, repentance and compassion. Another of them vindicates the Virgin Mary as patroness of peace and defender of good, and Pedro Nolasco as liberator of blacks, while giving a dissertation on the state of said social group. in the Cathedral of Puebla on Christmas Eve of 1689, and those made in 1690 to honor San José, also premiered in the Puebla cathedral.

In 2008, Alberto Pérez-Amador Adam, considering the corresponding musicological investigations carried out up to that moment, demonstrated that eleven of the villancicos accredited to Sor Juana are not hers, because they were put into musical meter by chapel masters in Spain and Spanish America long before its employment by Sor Juana. However, they must be considered as part of her work due to the fact that she retouched them to incorporate them into the Christmas carol cycles that were commissioned by the different New Spain cathedrals. The same researcher established a list of conserved Christmas carols from Sor Juana put into musical meter by composers from various cathedrals, not only in New Spain, but also in South America and the peninsula.

Biographical Documents

Different documents of a legal nature have been rescued. These are of particular importance for the reconstruction of different aspects of his biography.

- Request of Juana Inés de la Cruz, novicia of the convent of San Jerónimo, to grant his will and renunciation of property. February 15, 1669. (in Enrique A. Cervantes 1949)

- Testament and renunciation of goods of Joan Ines of the Cross, novitia of the convent of St. February 23, 1669. (in Enrique A. Cervantes 1949)

- Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz sells to her sister, Doña Josefa María de Asbaje, a slave. 6 June 1684. (in Enrique A. Cervantes 1949)

- Request by Juana Inés de la Cruz, religious of the convent of San Jerónimo, to impose on insured census on farms of that convent, the amount of $1400.00 pesos of common gold, property of the applicant. March 12, 1691.

- Census about $1400.00, insured on farms of the convent of San Jerónimo, which is established in favor of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. March 24, 1691. (in Enrique A. Cervantes 1949)

- Imposition of $600 more on goods and rents of the Convent of San Jerónimo, by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. August 18, 1691. (in Enrique A. Cervantes 1949)

- Sr. Juana Inés de la Cruz requests license from the Archbishop of Mexico, to buy the cell that was from Mother Catherine of San Jerónimo. 20 January 1692. (in Enrique A. Cervantes 1949)

- Sale of the cell that was from the mother Catherine of San Jerónimo to Sor Juana INés de la Cruz, February 9, 1692. (in Enrique A. Cervantes 1949)

- Vote and oath of the Immaculate Conception in the Convent of San Jerónimo of Mexico City. 1686 (in Manuel Ramos Medina 2011)

- Three Documents in the Book of Professions of the Convent of Saint Jerome (24 February 1669 / 8 February 1694 / no date) (in the fourth volume of the Complete works Mexico 1957: 522-523. Guillermo Schmidhuber, with the collaboration of Olga Martha Peña Doria, published a facsimile of Book of the Prophecies of the Convent of Saint Jeromecurrently kept at the Benson Library at the University of Texas in Austin.

- Guillermo Schmidhuber and Olga Martha Peña Doria edited the image and paleography of 64 documents in Parental and maternal families of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Documentary findings and 58 documents in The social networks of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, the majority previously unknown or lacking of published image; with a total of 122 documents, including the baptismal faith of Pedro de Asuaje, father of Sister Juana and the Permissions of passage from the Canary Islands to New Spain in 1598 of the paternal family of Sister Juana (Granma, Mother and Child Pedrito de Asuaje). As well as the paternal and maternal genealogical trees of Juana Inés with five generations and several documents from the Canary Islands that prove the immediate origin of the family from Genoa.

Lost Works

By various sources it is known of works that remain unpublished or that have been irretrievably lost. Alfonso Méndez Plancarte (in the first volume of the Complete Works, México 1951: XLIV) makes the following relation in this regard:

- A Loa to the Blessed Sacrament written at the age of eight and of which Diego Calleja news in his biography.

- The Caracol, a musical treatise you refer to in your romance After estimating my love.

- The moral balance. Moral practical directions in the safe probability of human actions. The manuscript was preserved by Carlos de Sigüenza and Góngora

- Sumules, a minor logic, which retained Fr. Joseph de Porras of the Society of Jesus at the Maximum College of St. Peter and St. Paul of Mexico.

- Other speeches to the finest of Christ our Lord

- Another role on the servant of God, Carlos de Santa Maria (a spiritual son of Father Núñez)

- A "gloss in tenths to the unprecedented religious action of our Catholic Monarch"

- The end of the Romance gratulatorio a los Cisnes de la España

- A poem (dramatic?) that left Augustine of Salazar and Torres unfinished. The second Celestina, a comedy initiated by Agustín de Salazar and Torres, who died in 1675 while writing it and finished it sor juana (Octavio Paz and Guillermo Schmidhuber proposed a release located in 1989 as the work of Sr Juana, Editorial Vuelta, 1990).

- «Other many discreet papers and letters», some in power of D. Juan de Orve and Arbieto

- Epistolario with Diego Calleja

- Epistolary with the Marquesa de la Laguna. Recently Beatriz Colombi and Hortensia Calvo published a collection of letters by Maria Luisa that are preserved in the library of the University of Tulaine in New Orleans.

Criticism and legacy

Sor Juana appears today as a very important playwright in the Spanish-American environment of the 17th century. In her time, however, it is possible that her theatrical activity occupied a secondary place. Although his works were published in Volume II (1692), the fact that the representations were restricted to the palace environment made their dissemination difficult, contrary to what happened with his poetry. The literature of the 18th century, mainly, praised the work de Sor Juana and instantly included it among the great classics of the Spanish language. Two editions of her works and numerous controversies endorse her fame.

In the 19th century, Sor Juana's popularity gradually faded, as evidenced by various expressions of 19th-century intellectuals. Joaquín García Icazbalceta speaks of an "absolute depravity of language"; Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo, of the arrogant pedantry of her baroque style, and José María Vigil of an "entangled and insufferable Gongorism."

From the interest that the Generation of '27 aroused by Góngora, writers from America and Spain began to reassess the poetess. From Amado Nervo to Octavio Paz —through Alfonso Reyes, Pedro Henríquez Ureña, Ermilo Abreu Gómez, Xavier Villaurrutia, José Gorostiza, Ezequiel A. Chávez, Karl Vossler, Ludwig Pfandl and Robert Ricard—, various intellectuals have written about the vast work of Sor Juana. All these contributions have made it possible to reconstruct, more or less correctly, the life of Sor Juana, and to formulate some hypotheses —unproposed until then— about the characteristic features of her production.

At the end of the 20th century, what is considered a Sor Juana contribution to La Segunda Celestina, proposed by Paz and Guillermo Schmidhuber, was discovered at the same time that Elías Trabulse made the Letter de Serafina de Cristo, attributed to Sor Juana. Both documents have unleashed a bitter controversy, still unresolved, among Sor Juana experts. Some time later, the process of the clergyman Javier Palavicino, who praised Sor Juana in 1691 and defended Vieira's sermon, was disseminated. In 2004, the Peruvian José Antonio Rodríguez Garrido gave an account of two fundamental documents for the study of Sor Juana: Defense of the Sermon on the Mandate of Father Antonio Vieira, by Pedro Muñoz de Castro, and the anonymous Apologetic speech in response to the errata issued by a soldier on the Athenagoric Letter of Mother Juana Inés de the Cross.

In 1992, in recognition of her figure, the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Award was created to distinguish the excellence of the literary work of women in Spanish in Latin America and the Caribbean.

At the movies

The figure of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz has inspired several cinematographic works inside and outside of Mexico. The best known, probably, is Yo, la peor de todas, an Argentine film from 1990, directed by María Luisa Bemberg, starring Assumpta Serna and whose script is based on Sor Juana Inés de the Cross or the traps of faith. Other films that take up the figure of the nun of San Jerónimo are the documentary Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz between heaven and reason (1996) and Las pasiones de sor Juana (2004). Likewise, it has also inspired the miniseries Juana Inés, produced by Canal Once and Bravo Films, with Arantza Ruiz and Arcelia Ramírez in the role of Sor Juana as a young woman and as an adult, respectively.

Editions

Old

- Castilian flooding of the only poetess, Musa Décima, dear Juana Inés de la Cruz, religious prophesied in the Monastery of San Jerónimo in the Imperial City of Mexico, which in several meters, languages and styles fertilizes various issues with elegant, subtle, clear, ingenious, useful verses, for teaching, recreation and admiration. Madrid: Juan García Infanzón, 1689. Reprinted with the title Poems.... Madrid, 1690; Barcelona, 1691; Zaragoza, 1692; Valencia, 1709 (two editions); Madrid, 1714; Madrid, 1725 (two editions). Contains 121 poems, five complete games of villancicos and the Allegorical Neptune along with the Explanation of the bow.

- Second volume of the works of Sr. Juana Inés de la Cruz, monja profesa in the monastery of Mr. San Jeronimo de la Ciudad de México, dedicated by the author to D. Juan de Orúe and Orbieto, knight of the Order of Santiago. Seville, Tomás López de Haro, 1692. Reprint in Barcelona, 1693 (three editions). With the title Poetic works, Madrid: 1715 and 1725. Includes sacramental cars, the Athenaetic Charter, Love is more labyrinth, The efforts of a house and seventy more poems.

- Fame and posthumous works of the phoenix of Mexico, tenth muse, American poet, Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz, religious profesa in the convent of San Jerónimo of the Imperial City of Mexico, consecrate them to the Catholic majesty of the queen Our Lady Doña Mariana de Neoburg Bavaria Palatina del Rhin, by the hand of Excma. Sra doña Juana de Aragón y Cortés, duques de Montoleón y Terranova, marquesa del valle de Oaxaca, el doctor don Juan Ignacio de Castorena y Ursúa, Capellán de Honor de su majestad, Protonotario, Judge Apostolico por su holiness, theologian, Examinar de la Nunciatura de España, prebendado de la Santa Iglesia Metropolitana de México. Madrid: Manuel Ruiz de Murga, 1700. Reprinted in Madrid in 1700, 1701 and 1714, and in Barcelona in 1725. It is composed of the Answer to Sor Filotea and several poems.

Modern

Complete Works

- Complete works, four tomos, edition and notes of Alfonso Méndez Plancarte. Mexico, Fund for Economic Culture, 1951-1957. Reissue of the first volume, Personal Lyric, by Antonio Alatorre, 2009.