Juan Manuel de Rosas

Juan Manuel de Rosas, born as Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rozas y López de Osornio (Buenos Aires, March 30, 1793 - Southampton, March 14 1877), was an Argentine rancher, soldier and politician who in 1829, after defeating General Juan Lavalle in the battle of Puente de Márquez, assumed the position of governor of the province of Buenos Aires, becoming, between 1835 and 1852, the main leader of the Argentine Confederation. His influence on Argentine history was so great that the period marked by his domination of national politics is known as the Rosas era.

Family origin and early years

Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rozas y López de Osornio was born on March 30, 1793 in Buenos Aires, capital of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. His birth took place on the land owned by his mother, Agustina López de Osornio, which his maternal grandfather Clemente López de Osornio had inhabited, located on the street that at that time was called Santa Lucía, current Sarmiento street between Florida and San Martin, in the city of Buenos Aires.

He was the son of the soldier León Ortiz de Rozas (Buenos Aires, 1760-1839) ―whose father was Domingo Ortiz de Rozas y Rodillo (Seville, August 9, 1721 - Buenos Aires, 1785) and his paternal grandfather, Bartolomé Ortiz de Rozas y García de Villasuso (b. Rozas del Valle de Soba, Spain, September 4, 1689) and, therefore, León was a great-nephew of Count Domingo Ortiz de Rozas, Governor of Buenos Aires from 1742 to 1745 and Captain General of Chile from 1746 to 1755― for which reason he belonged to the lineage of the Ortiz de Rozas who have their origin in the town of Rozas in the Soba valley, in La Montaña de Castilla la Vieja ―current Cantabria― belonging to the Crown of Spain.

He entered the private school run by Francisco Javier Argerich (1765-1824) at the age of eight, although from a young age he showed a vocation for rural activities; He interrupted his studies to participate, counting thirteen years of age, in the Reconquest of Buenos Aires in 1806 and later enrolled in the company of children of the Migueletes Regiment, fighting in the Defense of Buenos Aires in 1807, both made during the English invasions, where he was distinguished for his courage.

Later, he retired to his mother's field, a large ranch in the Buenos Aires pampas. When the events that culminated in the May Revolution of 1810 occurred, Rosas was 17 years old and remained outside them, the subsequent political evolution, and the Argentine war of independence.

In 1813, despite maternal opposition —which Rosas overcame by making his mother believe that the young woman was pregnant— he married Encarnación Ezcurra, with whom he had three children: Juan Bautista, born on July 30, 1814, María, born on March 26, 1816 and died the following day, and Manuela, known as Manuelita and born on May 24, 1817, who would later be her inseparable companion.

Shortly thereafter, due to a dispute he had with his mother, he returned the farms he managed to his parents to set up his own cattle and business ventures. He also changed his last name "Ortiz de Rozas" to "Rosas", symbolically cutting the family's dependence on him.

He was administrator of the fields of his cousins Nicolás and Tomás Manuel de Anchorena; The latter would occupy important positions within his government, since Rosas always had special respect and admiration for him. In partnership with Luis Dorrego -colonel Manuel Dorrego's brother- and with Juan Nepomuceno Terrero, he founded a saladero; it was the business of the day: salted meat and hides were almost the only export of the young nation. He amassed a great fortune as a cattle rancher and exporter of beef, distant from the emergent events that led the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata to emancipation from Spanish rule in 1816.

During those years, he met Dr. Manuel Vicente Maza, who became his legal sponsor, especially in a case that his own parents had filed against him. He later he was an excellent political adviser.

In 1818, due to pressure from meat suppliers in the capital, the Supreme Director of the River Plate, Juan Martín de Pueyrredón, took a series of measures against the saladeros. Rosas quickly changed his line of business: he dedicated himself to agricultural production in partnership with Dorrego and the Anchorenas, who also entrusted him with the management of their Camarones ranch, south of the Salado River.

The following year he bought the ranch Los Cerrillos, in San Miguel del Monte. There he organized a cavalry company (shortly increased to a regiment), the Colorados del Monte, to fight the indigenous people and the rustlers of the Pampas area. He was named its commander, and rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

At that time he wrote his famous Instructions to the mayordomos of estancias, in which he precisely detailed the responsibilities of each of the administrators, foremen, and laborers. In that little book he demonstrated his ability to simultaneously manage several farms with very effective methods, in anticipation of his future ability to manage the provincial state.

The beginnings in politics

Until 1820 Juan Manuel de Rosas dedicated himself to his private activities. From that year until his fall in the Battle of Caseros, in 1852, he dedicated his life to political activity, leading ―whether in government or out of it― the province of Buenos Aires, which had not only one of the territories richest productive sectors of the nascent Argentina, but with the most important city ―Buenos Aires― and the port that concentrated the foreign trade of the remaining provinces, as well as the customs import duties (controlled until 1865 by the province of Buenos Aires). A large part of the institutional conflicts and Argentine civil wars of the 19th century developed in relation to these resources.

In 1820, the period of the Directorate ended with the resignation of José Rondeau as a result of the Battle of Cepeda that gave way to the Anarchy of the XX Year. It was at that time that Rosas began to get involved in politics, by helping to reject the invasion of the caudillo Estanislao López at the head of his Colorados del Monte. He participated in Dorrego's victory in the battle of Pavón but together with his friend Martín Rodríguez refused to continue the invasion towards Santa Fe, where Dorrego was completely defeated in the battle of Gamonal.

With the support of Rosas and other ranchers, his colleague General Martín Rodríguez was elected governor of the Province of Buenos Aires. On October 1, a revolution broke out, led by Colonel Manuel Pagola, who occupied the center of the city. Rosas made himself available to Rodríguez, and on the 5th he began the attack, completely defeating the rebels. The chroniclers of those days recalled the discipline that reigned among the gauchos of Rosas, that he was promoted to the rank of colonel. With Martín Rodríguez, the group of ranchers began to have a public role.

He was also part of the negotiations that concluded with the Treaty of Benegas, which put an end to the conflict between the provinces of Santa Fe and Buenos Aires. He was responsible for complying with one of its secret clauses: delivering 30,000 head of cattle to Governor Estanislao López as reparation for the damage caused by the Buenos Aires troops in his territory. The clause was secret, so as not to "stain the honor" of Buenos Aires. Thus began the permanent alliance that this province would have with that of Buenos Aires until 1852.

The first years after the dissolution of national powers were a period of peace and prosperity in Buenos Aires, known as the "happy experience", mainly because Buenos Aires used the Customs revenues for its exclusive benefit, an inexhaustible source of wealth that the province decided not to share with its sisters or with outside armies.

Between 1821 and 1824 he bought several more fields, especially the ranch that had belonged to Viceroy Joaquín del Pino y Rozas (known as Estancia del Pino, in the La Matanza district), which he named San Martín in honor of the general Jose de San Martin.

He also took advantage of the emphyteusis law promoted by Minister Bernardino Rivadavia to increase his fields. Instead of helping small landowners, this law ended up leaving nearly half of the province's area in the hands of a few large landowners.

The disorders produced by the Anarchy of the Year XX had left the southern border unguarded, which is why the raids had intensified. Martín Rodríguez then led three campaigns into the desert, using a strange mixture of peace and war dialogues with the indigenous people. In 1823 he founded Fuerte Independencia, the current city of Tandil. In almost all these campaigns he was accompanied by Rosas, who also participated in an expedition in which the surveyor Felipe Senillosa delineated and established cadastral plans for the towns in the south of the province. The nominal head of that campaign was Colonel Juan Lavalle.

During the war in Brazil, President Rivadavia appointed him commander of the field armies in order to keep the border pacified with the indigenous population of the Pampas region, a position he held again later, during the provincial government of Colonel Dorrego.

Rosas enthusiastically approved the Peace Convention of 1828, which recognized the independence of Uruguay. He wrote to Tomás Guido, one of his signatories: & # 34; What opium fruits the Republic has given (...) the legation of his sons (Guido and Balcarce) to Janeiro! (...) the most honorable peace that we could promise ourselves. (...) the war has ended in such a way that it fills us with a noble elation... It is my obligation to pay you the greatest gratitude".

In 1827, in the context prior to the start of the civil war that would break out in 1828, Rosas was a military leader, representative of rural owners, socially conservative and identified with the colonial traditions of the region. He was aligned with the federalist, protectionist current, adverse to foreign influence and to the free trade initiatives advocated by the Unitary Party.

The December Revolution

After the War in Brazil, the governor of the Province of Buenos Aires, Manuel Dorrego, ―due to intense diplomatic and financial pressure― signed a peace treaty that recognized the independence of Uruguay, and the free navigation of the Río de la Silver and its tributaries only by Argentina and the Empire of Brazil but for a limited term of fifteen years; what was seen by members of the army in operations as a betrayal. In response, on the morning of December 1, 1828, the unitary general Juan Lavalle took the Fort of Buenos Aires and gathered members of the unitary party in the church of San Francisco ―nominally as representation of the people―, being elected governor. Following the same logic, he dissolved the Board of Representatives of Buenos Aires.

Juan Manuel de Rosas launched the campaign against the rebels and gathered a small army of militiamen and federal parties, while Dorrego withdrew to the interior of the province to seek their protection. Lavalle went with his troops to the campaign to face the federal forces of Rosas and Dorrego, whom he attacked by surprise in the battle of Navarro, defeating them.

Due to the existing disparity between the seasoned and experienced rebel forces under the command of Lavalle, with respect to the militias that defended Governor Dorrego, Rosas advised him to retire to Santa Fe, to join forces with those of Estanislao López, but the governor refused. While Rosas withdrew to Santa Fe for that purpose, Dorrego decided to take refuge in Salto, in the regiment of Colonel Ángel Pacheco. But, betrayed by two of his officers ―Bernardino Escribano and Mariano Acha―, he was sent prisoner to Lavalle.

As Rosas criticized his lack of foresight in the face of the unitary revolution, Dorrego replied:

Mr. Don Juan Manuel: that you want to give me political lessons, is as advanced as if I proposed to teach you how to govern a stay.Manuel Dorrego

Defeated and taken prisoner by Dorrego, Lavalle, influenced by the desire for revenge of the Unitarian ideologues, ordered his execution and took full responsibility.

In his last letter, written to Estanislao López, Dorrego asked that his death not be a cause of bloodshed. Despite this request, his execution gave way to a long civil war, the first in which almost all the Argentine provinces were simultaneously involved.

At the beginning of January 1829, General José María Paz, an ally of Lavalle, began the invasion of the province of Córdoba, where he would overthrow the governor Juan Bautista Bustos. In this way, the civil war spread throughout the country.

Lavalle sent armies in all directions, but several small caudillos allied to Rosas organized resistance. The unitary chiefs resorted to all kinds of crimes to crush it, a fact little publicized by the historiography of the Argentine civil wars.

Governor Lavalle sent Colonel Federico Rauch to the south, and one of his columns, commanded by Colonel Isidoro Suárez, defeated and captured Major Manuel Mesa, who was sent to Buenos Aires and executed. At the head of the bulk of his army, Lavalle advanced to occupy Rosario. But, soon after, López left Lavalle without horses, who was forced to turn back. López and Rosas pursued Lavalle to near Buenos Aires, defeating him at the Battle of Puente de Márquez, fought on April 26, 1829.

While López was returning to Santa Fe, Rosas besieged the city of Buenos Aires. There opposition to Lavalle grew (despite the fact that Dorrego's allies had been expelled), especially because of the crime against the governor. Lavalle increased the persecution of critics, which would bring a lot of support to Rosas, in the city that has always been the capital of Unitarianism.

Lavalle, desperate, launched into something unusual: he headed, completely alone, to Rosas' headquarters, the Estancia del Pino. Since he was not there, he lay down to wait for him on Rosas's campaign cot. The following day, June 24, Lavalle and Rosas moved to the La Caledonia ranch ―owned by a certain Miller―, where they signed the Pact of Cañuelas, which stipulated that elections would be called, in which only a list of federal and unitary unity would be presented, and that the candidate for governor would be Félix de Álzaga.

Lavalle introduced the treaty with a message that included an unexpected take on his enemy:

My honor and my heart impose on me to remove all the inconveniences for perfect reconciliation...And above all the case has come that we see, treat and know about Juan Manuel de Rosas as a true patriot and lover of order.Juan Lavalle

But the Unitarians presented the candidacy of Carlos María de Alvear, and at the price of thirty deaths they won the elections. Relations were broken again, forcing Lavalle to a new treaty, the Pact of Barracas, of August 24. But, now more than before, the force was on Rosas's side. Through this pact Juan José Viamonte was appointed governor. He called the legislature overthrown by Lavalle, paving the way for Rosas to power.

First government

The legislature of Buenos Aires proclaimed Juan Manuel de Rosas as Governor of Buenos Aires on December 8, 1829, also honoring him with the title of Restorer of the Laws and Institutions of the Province of Buenos Aires, and in the same act He granted him "all the ordinary and extraordinary powers that he believed necessary, until the meeting of a new legislature." It was not something exceptional: extraordinary powers had already been conferred on Manuel de Sarratea and Martín Rodríguez in 1820, and on the governors of many other provinces in recent years; Juan José Viamonte had also had them.

The same day he was sworn in, he declared to the Uruguayan diplomat Santiago Vázquez:

They think I'm federal; not sir, I'm not a party but a homeland... Anyway, all I want is to avoid evil and restore institutions, but I feel like they brought me to this position.

The first thing that Rosas did was hold an extraordinary funeral for General Dorrego, bringing his remains to the capital, with which he achieved the adhesion of the followers of the deceased federal leader, adding the support of the humble people of the capital to those who already had of the rural population.

Regarding the constitutional form of organization of the state and federalism, Rosas was a pragmatist. In letters sent in 1829 to General Tomás Guido, General Eustoquio Díaz Vélez and Braulio Costa, Quiroga's financier wrote to inform them that

... General Rosas is unitarian at first, but that the experience has made him know that it is impossible to adopt such a system in the day because the provinces contradict it, and the masses in general hate it, because at last it is only to move by name.

The civil war in the interior

General José María Paz had occupied Córdoba and defeated Facundo Quiroga. Rosas sent a commission to mediate between Paz and Quiroga, but he was defeated and took refuge in Buenos Aires. Rosas made him give a triumphant welcome - as if he had been the winner - although the caudillo considered that the war was over for him.

Paz took advantage of the victory to invade the provinces of Quiroga's allies, placing unitary governments there. The sides were defined: the four coastal provinces, federal; the nine in the interior, unitary and united since August 1830 in a Unitary League, whose "supreme military chief" was Paz.

A few months later, in January 1831, Rosas and Estanislao López promoted the Federal Pact between Buenos Aires, Santa Fe and Entre Ríos. This ―which would be one of the "pre-existing pacts" mentioned in the Preamble of the Constitution of the Argentine Nation― had the objective of putting a brake on the expansion of unitarism embodied in General Paz. Corrientes would later adhere to the Pact, because Corrientes deputy Pedro Ferré tried to convince Rosas to nationalize the revenue of the Buenos Aires customs and impose customs protections on local industry. On this point, Rosas would be as inflexible as his Unitarian predecessors: the main source of wealth and power in Buenos Aires came from customs.

The Santiago leader Juan Felipe Ibarra, a refugee in Santa Fe, managed to get López to initiate actions against Córdoba. They would be guerrilla actions, because in that type of action he had an advantage over the disciplined troops of Paz. At the beginning of 1831, the Buenos Aires army also began operations, under the command of Juan Ramón Balcarce; but the Buenos Aires army never came to join the Santa Fe army.

When Colonel Ángel Pacheco defeated Juan Esteban Pedernera in the battle of Fraile Muerto, Paz decided to personally take charge of the eastern front.

For his part, Quiroga decided to return to the fight. He asked Rosas for strength, but he only offered him the prisoners in the jails. Quiroga set up a training camp and, when he considered himself ready, he advanced on the south of Córdoba. On the way, Pacheco gave him the past of Fraile Muerto: with them he conquered Cuyo and La Rioja in just over a month.

The unexpected capture of Paz by a boleadoras shot by a López soldier, on May 10, 1831, caused a sudden change: Gregorio Aráoz de Lamadrid took charge of the unitary army, with which he retreated to the north and he was defeated by Quiroga in the battle of La Ciudadela, on November 4, next to the city of Tucumán, with which the Interior League was dissolved.

Santa Fe Convention

In the following months, the remaining provinces adhered to the Federal Pact: Mendoza, Córdoba, Santiago del Estero and La Rioja in 1831. The following year, Tucumán, San Juan, San Luis, Salta and Catamarca.

As soon as the war ended, the representatives of several provinces announced that, with internal pacification, the awaited occasion for the constitutional organization of the country had arrived. But Rosas argued that the provinces had to be organized first and then the country, since the constitution had to be the written result of an organization that had to happen first. He took advantage of an accusation by the Corrientes deputy Manuel Leiva to accuse him of having anarchic ideas and withdraw his representative from the Santa Fe convention. In August 1832, the convention was dissolved, and the opportunity to constitutionally organize the country it was postponed for another twenty years.

For a time, the country was divided into three areas of influence: Cuyo and the northwest, of Quiroga; Córdoba and the coast, by López; and Buenos Aires, from Rosas. For a few years, this virtual triumvirate would rule the country, although relations between them were never very good.

In 1832, in a letter to Quiroga, Rosas told him

... being federal by intimate conviction, I would subordinate myself to being unitary if the people's vote was for unity.

The government of the province

The first government of Rosas in the Province of Buenos Aires was a government "of order"; It was not a despotic tyranny, although later historians would extend to his first government some characteristics of the second. At this first moment, he relied on some of the leaders of the Order Party of the previous decade, which has allowed him to be accused of being the continuation of the Unitary Party, although over time he would distance himself from them.

Among the negative events, responsibility was attributed to him in the British invasion of the Malvinas Islands, although this event occurred on January 3, 1833, during the government of Balcarce, who had succeeded Rosas, who was undertaking his campaign to desert. These islands, which had been the object of dispute between Spain and England, were in Spain's possession at the time Argentine independence was declared, and England implicitly recognized the legal continuity of Argentine rights over Spanish possessions when it celebrated the Friendship Treaty, Commerce and Navigation, signed in Buenos Aires on February 2, 1825, a few years after Argentine Independence and ratified by the British government in May of that same year. In addition, the Malvinas Islands had been populated by the Government of Buenos Aires and a governor had been appointed.

This first administration of Rosas was also a progressive government: towns were founded, the Code of Commerce and the Code of Military Discipline were reformed, the authority of the justices of the peace of the towns in the interior was regulated, and treaties were signed of peace with the caciques, with which a certain tranquility was obtained on the border.

However, the supremacy achieved was not associated with the unconditional support of the entire population. On the contrary, Rosas had to face stiff resistance during the course of his government.

Interregnum

At the end of 1832, the Buenos Aires Legislature re-elected Rosas. It was said for many years that he rejected his re-election because he was not granted extraordinary powers, which is not accurate: he did not feel capable of governing -nor did he want to- without the unanimity of public opinion in favor of he. He would wait for them to call him desperately, while he searched for a way to make himself essential.

In his place was elected Juan Ramón Balcarce, an important soldier from the time of the Argentine War of Independence and head of a non-Rosista federal group, to whom Rosas handed over the government on December 18, 1832.

Campaign to the Desert

The Buenos Aires Pampas plain had been subject to white rule only in a narrow strip along the Paraná River and the Río de la Plata, at least until the 1810s. Since then, the "frontier with the Indian" had been advanced to a line that passed approximately through the current cities of Balcarce, Tandil and Las Flores.

As soon as Rosas left the government at the end of 1832, at the beginning of the following year he coordinated the campaign with those of Mendoza, San Luis and Córdoba to make a general raid, which would also accompany the other one that had begun at the beginning of the same year General Manuel Bulnes in Chile and in the extreme northwest of eastern Patagonia, specifically in the surroundings of the Epulafquen lagoons. The general command was offered to Facundo Quiroga, but he did not participate in it. Rosas concentrated and trained the troops at his ranch in Los Cerrillos, near the fort and town of San Miguel del Monte.

On February 6, 1833, the law was approved that authorized the Executive Branch to negotiate a credit of one and a half million pesos m/c, to pay for the expenses of the expedition, although soon after, the Minister of War He communicated that he could not take charge of said objective, and for which Rosas and Juan Nepomuceno Terrero ended up supplying cattle and horses for supplies, added to their Anchorena cousins, Dr. Miguel Mariano de Villegas, Victorio García de Zúñiga and then Colonel Tomás Guido donated money in cash so they could start it, therefore, they were able to depart from there in March of that year.

The western column, under the command of José Félix Aldao, crossed a territory that had recently been "cleansed" of aborigines, so it limited itself to reaching the Colorado River. The one in the center defeated the ranquel cacique Yanquetruz and quickly returned. The one that did most of the campaign was the one in the east, under the command of Rosas himself. He established himself on the banks of the Colorado River ―near the current town of Pedro Luro― and sent five columns to the south and west, which managed to defeat the most important caciques. He then signed peace treaties with others, hitherto secondary, who became useful allies. The following year the most important of them, Calfucurá, joined.

During the first years of his second government, Rosas's policy towards the indigenous peoples alternated peace treaties and donations with extermination campaigns. Only after the crisis that began in 1839 did he change it to a permanent peace policy.

The campaign also involved scientists who gathered information about the area covered, but the desert regions remained in the hands of the indigenous people. He also received a visit from the scientist Charles Darwin, who in his travel diary described part of the campaign:

The Indians formed a group of about 110 people (men, women and children); almost all were made prisoners or dead, as soldiers do not give barracks to any man. The Indians currently feel such a great terror, that they no longer resist in mass; each hasten to flee separately, abandoning women and children. [...] No dispute, those scenes are horrible, but the more horrible the fact that soldiers kill all the Indians who seem to be over twenty years old is still true! And when I, in the name of mankind, protested, replied, "What else can we do? They have so many children these savages!"

Tranquility was ensured for the fields and towns already formed, and a relative advance was achieved in the southwest of the province, but the advances of the frontier were much less spectacular than those achieved in the Conquest of the Desert undertaken much later by General Julio Argentino Roca in 1879.

The most important thing that Rosas achieved was to get the army, the ranchers and public opinion to his side. And the gratitude of the provinces of Mendoza, San Luis, Córdoba and Santa Fe, which were free of significant looting for many years. However, the only group of aborigines that was not fully dominated, the Ranqueles, continued to be seen as a problem for the inhabitants of these provinces.

The price to pay for peace was to support the friendly tribes with annual deliveries of cattle, horses, flour, cloth and brandy. From this moment on, the hunting tribes depended on food deliveries, and were considered by the people of Buenos Aires as costly parasites of the public treasury, forgetting that -from Rosas's point of view- the payments were a price to pay for the use of territories that they considered theirs. This pacifying attitude, and the fulfillment of the pacts concluded, earned Rosas the respect of some of the chiefs of the friendly Indians. When he assumed the governorship of the province for the second time, the cacique Catriel in Tapalqué declared:

Juan Manuel is my friend. He's never cheated on me. Me and all my Indians will die for him. If it had not been for Juan Manuel, we would not live as we live in fraternity with Christians and among them. As long as Juan Manuel lives we will all be happy and spend a quiet life next to our wives and children. All who are here can testify that what Juan Manuel has told us and advised has come well.

Years after the fall of Rosas, Catriel himself pointed out:

Our brother Juan Manuel was a blond Indian and a giant who came into the desert passing to the Samborombón and the Salado and who rode and snooped like the Indians and snooped with the Indians and gave us cows, mares, cane and silver garments, while he was Cacique General never the Malon Indians invaded, for the friendship we had for Juan Manuel. And when the Christians threw him out and banished him, we all invaded together.quoted by Julio A. Costa en Rock and Weaver

Later, Rosas himself directed the writing of a Grammar of the Pampas language.

In this campaign, some officers who formed the next generation of Buenos Aires soldiers stood out: Pedro Ramos, Ángel Pacheco, Domingo Sosa, Hilario Lagos, Mariano Maza, Jerónimo Costa, Pedro Castelli and Vicente González (the Carancho del Monte ).

A characteristic element of the campaign were the so-called saints, which were small messages that served as communication between Buenos Aires and the expedition through a system of 21 posts established during the campaign.

The Revolution of the Restaurateurs

While Juan Manuel de Rosas was in his camp on the Colorado River, internal disagreements within the federal party were growing. One of the fractions was ideologically liberal and wanted constitutional organization; Governor Balcarce and his ministers Enrique Martínez and Félix Olazábal were active in its ranks. Their adversaries, loyal to Rosas, called them black backs because the back of the list on which they were running was black. In Rosas's party there were ranchers, soldiers, and retail merchants.

The confrontation was conducted mainly in the press, divided into two camps, which scandalously attacked each other; the government decided to prosecute various opposition and pro-government newspapers. Then Encarnación Ezcurra, Rosas's wife and adviser, who gathered her allies daily in her house, and organized the demonstrations, took action.

When the trial was announced to the newspapers, one of them was called "The Restorer of the Laws." Encarnación had the city papered with the news that the Restorer was going to be tried, which the people interpreted as a trial of the head of the federal party. A large demonstration ensued, and its participants gathered on the outskirts of the city; General Agustín de Pinedo, who had been sent to suppress the demonstration, revolted his men and assumed leadership of the demonstration, turning it into a siege of the city. A few days later Balcarce resigns.

It should be noted, as the historian José María Rosa does, that this is a very peculiar revolution for the time:

It was not a “revolution” in the sense that today we give the floor, but a retreat from the people to Barracas, a general strike – the first of our history – without fighting or street struggles. The “vigilantes” of Balcarce are useless, defectifying the restorationists; useless their regiments, which disobey their bosses.

After the fall of Balcarce, the Chamber appoints General Juan José Viamonte, inheriting the political fragility of his predecessor.

A few months later, Rosas arrived in Buenos Aires, and Viamonte was forced to resign. In his place, Rosas was elected, but he did not accept because he was not granted extraordinary powers . He did not feel capable of governing under the limitations of a rule of law. His friend Manuel Vicente Maza, president of the legislature, was elected governor.

Second government

When a conflict broke out between Salta and Tucumán, Rosas managed to get the governor of the Province of Buenos Aires, Manuel Vicente Maza, to send General Facundo Quiroga, who lived in Buenos Aires, as a mediator. On the way, he was ambushed and assassinated in Barranca Yaco, Córdoba province, on February 16, 1835 by Santos Pérez, a hitman linked to the Reynafé brothers, who ruled Córdoba.

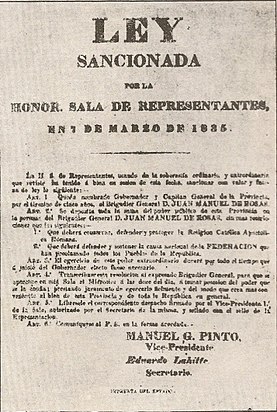

The death of Quiroga caused a climate of instability and violence, for which Maza submitted his resignation on March 7 of that year. The Buenos Aires Legislature called Rosas to take charge of the provincial government. Rosas conditioned his acceptance on being granted the "sum of public power", by which the representation and exercise of the three powers of the state would fall on the governor, without the need to render an account of his exercise. The legislature accepted this imposition, issuing the corresponding law that same day.

The amount of public power was granted with the commitment to:

- To preserve, defend and protect the Catholic religion.

- Sustain the national cause of the Federation.

- The exercise of the sum of public power would last “every time the Governor considers necessary”.

He did not dissolve the legislature or the courts; for the moment, the amount of power appeared as the legal sanction of the exceptional nature of his mandate. The dictatorial nature of that political institution would surface later, when Rosas made use of all that power.

On the other hand, this assassination caused an imbalance in the dominant figures of Argentine politics: when Quiroga died, only Rosas and López would remain as possible federal leaders. This, while protector of the Reynafé, was very weakened; and would die in the middle of 1838. As time passed, the persuasiveness of his diplomacy and the skill of his leadership would earn Rosas the respect and accompaniment of other leaders of the interior, such as Juan Felipe Ibarra, from Santiago del Estero, and Jose Felix Aldao, from Mendoza.

Because the country did not have its own constitution at that time ―its fall would be, in 1853, a necessary condition for its sanction― the powers enjoyed by Rosas in his second term have been superior to those of a president of facto, since within these he included that of administering justice, although the legislation in which Rosas moved in his time should not be downplayed, particularly the laws of the Indies and the Federal Pact, since it is usually believed that Rosas acted in Argentine politics without any restraint, but his letters and personal documents reveal the great fidelity that he had to the legislation given by the Spanish empire and that remained in force until 1853. Much of Argentine historiography continues to consider Rosas a dictator or a tyrant, while the revisionist current denies him that character, considering him a defender of national sovereignty.

Before taking over as governor, the Restorer demanded that a plebiscite be held to confirm popular support for his election. The plebiscite was held between March 26 and 28, 1835 and its result was 9,713 votes in favor and 7 against. At that time, the province of Buenos Aires had 60,000 inhabitants, of whom women and children did not have access to suffrage.

The Chamber of Representatives appointed Rosas governor on April 13, 1835 for the five-year period from 1835 to 1840.

The speech that Rosas gave at the Fort, seat of the provincial government, at the time of assuming his second term as governor would characterize his position towards his opponents:

The divine providence has put me in this terrible situation. We despise those who have put our land into confusion; let us persecute the wicked, the thief, the sacrilege, and above all the perfidious traitor who has the daring to mock our good faith. Let that race of monsters not remain one among us and let their persecution be so tenacious and vigorous that it will serve as terror and terror to others who can come forward! It will take us away from any kind of danger, nor the fear of wandering in the means we adopt to pursue them.

Rosas assumed his new government with the sum of the public power that he used to harass his dissidents, whether they were federal or unitary.

There is no news of any citizen who would not vote. I must put it in a sense of historical truth, there was never a more popular and desired government, or rather held by opinion. The unitaries who had taken part in nothing received it at least with indifference, the feds Black.with disdain, but without opposition; the peaceful citizens expected it as a blessing and a term to the cruel two-long oscillations; the campaign, finally, as the symbol of their power and the humiliation of the goods CITY. [...]Consider how it may have happened that in a province of four hundred thousand inhabitants, as assured by the GacetaWould there only be three votes contrary to the government? Would it be that the dissidents didn't vote? None of that! There is still no news of any citizen who was not to vote; the sick rose from the bed to go to give their apprehension, afraid that their names would be inscribed in some black record; for so it had been insinuated. [...]

Terror was already in the atmosphere, and even though thunder had not exploded yet, they all saw the black and torva cloud coming over the sky.Faustino Sarmiento

In this sense, a vivid portrait of that time has been the legacy by the pen of Esteban Echeverría in El matadero, a precursor story of Río de la Plata realism that takes place in the province of Buenos Aires during the decade from 1830. From the opposition point of view, Echeverría described the contests between unitarios and federales, and the figures of the caudillo Rosas and his followers, attributing to the latter brutal and bloodthirsty qualities.

As soon as he took office, Rosas ordered the capture of Santos Pérez and the Reynafés, and after a trial that took years, they were sentenced to death and executed. The trial gave Rosas national authority in an unexpected realm: his province had a nationally authoritative criminal court. That authority was not legal but it was real, and it brought a certain unity to the national administration.

He removed his opponents from all public posts: he expelled all public employees who were not “net” federales, and he erased from the military ranks officers suspected of being opponents, including exiles. He then made the motto "Federation or death" obligatory, which would gradually be replaced by "Death to the unitary savages!", to head all public documents; and he imposed the use of the punzó headband on public and military employees, which would soon be worn by all.

Among the officials separated from their position by order of the governor was Dr. Miguel Mariano de Villegas, who was dean of the Superior Court of Justice, for not deserving the government's trust.

Due to opposition, later the Unitarians would carry light blue emblems, which would have an unexpected result: the Argentine flag was, until then, blue and white. Rosas' armies began to use it with a dark blue, almost violet color; To differentiate themselves, the Unitarians used it in light blue and white.

To achieve his political objectives, Rosas also had the support of the Popular Restoration Society, with which his wife Encarnación was especially linked at that time, made up of the most loyal group of his supporters. And through the Mazorca vigilante body, which he returned to act in the persecution of his adversaries.

Once he managed to consolidate his power, he imposed federal criteria and formed alliances with the leaders of the other provinces Argentine, achieving control of trade and foreign affairs of the Confederation.

Customs Law

The governor of Corrientes, Pedro Ferré, made an energetic statement demanding protectionist measures for products of local origin, whose production was deteriorating due to the free trade policy of Buenos Aires.

On December 18, 1835, Rosas sanctioned the Customs Law in response to this proposal, which determined the prohibition of importing some products and the establishment of tariffs for other cases. Instead he kept import duties low on machines and minerals that were not produced in the country. With this measure he sought to win the good will of the provinces, without giving up the essentials, which were the Customs entrances. These measures notably boosted the domestic market and production in the interior of the country. Thanks to the privileged position that Buenos Aires occupies, it was consolidated as the main commercial city of the country, since it was much more profitable to trade with Buenos Aires than with other river or inland cities.

It was born from a basic import tax of 17% and was increased to protect the most vulnerable products. Vital imports such as steel, brass, coal, and farm tools were taxed at 5%. Sugar, beverages and food products 24%. Footwear, clothing, furniture, wine, cognac, liquor, tobacco, oil and some leather items 35%. Beer, flour and potatoes 50%.

The unexpected effect, but one that Rosas had considered correctly, was that imports decreased, but the growth of the domestic market made up for that drop. In fact, import taxes increased significantly. Later, under the effect of the blockades, these import rates were reduced (without being as low as they were before and after the Rosas government).

Simultaneously, he tried to force Paraguay to join the Argentine Confederation by suffocating it economically, for which he imposed a heavy tax on tobacco and cigarettes. Since he feared that they would enter smuggling through Corrientes, those taxes also reached products from Corrientes. The measure against Paraguay failed, but it would have serious consequences for Corrientes.

His economic policy was decidedly conservative: he controlled expenses to the maximum, and maintained a precarious fiscal balance without issuing currency or indebtedness. He also did not pay the external debt contracted in Rivadavia's time, except in small sums during the few years when the Río de la Plata was not blocked. The Buenos Aires paper money kept its value very stable and circulated throughout the country, replacing the Bolivian metallic currency, thus contributing to the monetary unification of the country. The National Bank founded by Rivadavia was controlled by English merchants and had caused a serious currency crisis with continuous issues of paper money, continuously depreciated. In 1836, Rosas declared him missing, and in his place he founded the Banco de la Provincia de Buenos Aires.

His administration was extremely meticulous, meticulously writing down and reviewing public expenses and income, and publishing them almost monthly. Even when he later punished his enemies with seizures of their assets -he did not confiscate them, unlike what Lavalle did before him, or Valentín Alsina and Pastor Obligado later-, he had them handed over to the relatives of those punished detailed receipts of everything seized.

Foreign Policy

In the north, the ambitions of the Bolivian dictator Andrés de Santa Cruz, who dominated the recently founded Peru-Bolivian Confederation and wanted to invade Jujuy and Salta with the support of some Unitarian émigrés, led to a war between those countries and Argentina. The war was in charge of Alejandro Heredia, governor of Tucumán. This was the last of the federal caudillos who overshadowed Rosas, but the Restorer managed to discipline him by financing this war. At the end of 1838, with the assassination of Heredia at the hands of one of his officers, operations came to a standstill and his last federal competitor disappeared. The internal adversaries that would appear from the following year would no longer be competitors for control of federalism, but decidedly enemies of the rosista system.

Relations with Brazil were very bad, but it never came to war, at least until the crisis that would lead to the Battle of Caseros. There were never any problems with Chile, although many opponents took refuge in that country, and they even launched some expeditions from there against the Argentine provinces. Paraguay proclaimed its independence and officially announced it to Rosas, who replied that he was not in a position to recognize or ignore that declaration. In practice, his intention was to reincorporate the former province of Paraguay into the Confederation, for which he maintained the blockade of the interior rivers, in order to force Paraguay to negotiate. Paraguay responded by allying itself with Rosas's enemies, but there was never any confrontation between the two armies or squads.

In Uruguay, the new president Manuel Oribe freed himself from the tutelage of his predecessor Fructuoso Rivera; but he, with the support of the Unitarians from Montevideo (including Lavalle) and the Brazilian imperialists established in Rio Grande do Sul, formed the "colorado" party - to which Oribe was opposed by the "white" party - and launched the revolution beginning the so-called Great War. In the middle of 1838, the colorados began to siege the government, sheltered behind the walls of Montevideo. The colorados had from the first moment the support of the French fleet and the Brazilian protectorate. Given this, Oribe resigned in October 1838, making it clear that he had been forced by a foreign fleet, and retired to Buenos Aires.

Rosas had decided to suspend the payments of the debt acquired in 1824 by the Government of Buenos Aires with the British house Baring Brothers, and in 1838 he appointed Manuel Moreno as diplomatic representative in London to offer to the British Crown, so unofficially, a full cancellation of the debt (£1 million) in exchange for dropping the claim on the islands. Rosas would use the Malvinas again in 1842 to demand economic compensation from the United Kingdom for the occupation of the islands, in order to postpone debt payments. This agreement is known as the “Falconnet Arrangement”, after Frank de Pallacieu Falconnet, who was envoy for Baring Brothers to negotiate with the Rosas government.

The French blockade

The worst problems began with France: French foreign policy had remained in a low profile for two decades, until King Louis-Philippe tried to restore France to its role as a great power, forcing several weak countries to make trade concessions and, when possible, reduce them to protectorates or colonies. That was the case in Algeria, just to cite one example. Since 1830, France sought to increase its influence in Latin America and, especially, to achieve the expansion of its foreign trade. Aware of English power, in 1838 King Louis Philippe explained to Parliament that "only with the support of a powerful navy could new markets be opened for French products."

In November 1837, the French vice-consul appeared before the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Felipe Arana, demanding the release of two French prisoners, the engraver César Hipólito Bacle, accused of espionage for Santa Cruz, and the smuggler I washed. He also demanded an agreement similar to the one that the Argentine Confederation had with England and the exception of military service for its citizens (which at that time were two).

Arana rejected the demands, and months later, in March 1838, the French navy blocked "the port of Buenos Aires and the entire coastline of the river belonging to the Argentine Republic." And he extended it to the other coastal provinces, to weaken Rosas's alliance with them, offering to lift the blockade against each province that broke with him.

Also in October 1838, the French squadron attacked Martín García Island, defeating the forces of Colonel Jerónimo Costa and Major Juan Bautista Thorne with their cannons and numerous infantry. Due to the honorable and courageous performance shown by the Argentines, they were taken to Buenos Aires and released, with a note from the French commander Hipólito Daguenet, informing Rosas of this circumstance, in the following terms:

...in charge of Mr. Admiral Le Blanc, commander-in-chief of the station of Brazil, and of the seas of the Sud, to take over the island of Martin García with the forces placed at my disposal for such an object, I carried out on 14 of this mission that had been entrusted to me. She has presented me with the opportunity to appreciate the military talents of the bravo Colonel Costa, governor of that island and her animosity towards her country. This very frankly manifested opinion is also that of the captains of French corvettes the Expéditive and the Bordelaise, witnesses of the incredible activity of Colonel Costa, as of the correct provisions made by this superior officer, for the defense of the important position he was in charge of preserving. Filled with estimation by him I thought I could not give him a better proof of the feelings he has inspired me, that manifesting V.E. his bizarre conduct during the attack directed against him, the 11th of the current, by forces far superior to those of his command...

The blockade greatly affected the economy of the province, by closing the possibilities of exporting. That left ranchers and merchants very unhappy, many of whom quietly went over to the opposition.

Regarding France's particular claim, that is, the exemption from the arms service for its subjects, the government of Buenos Aires delayed the response for more than two years. Rosas was not opposed to recognizing the French residents in the Río de la Plata the right to treatment similar to that given to the English, but he was only willing to recognize it when France sent a plenipotentiary minister, with full powers to sign of a treaty. That meant equal treatment, and recognition of the Argentine Confederation as a sovereign state.

Controlled journalism

With the arrival of Rosas to power, any possibility of freedom of expression in journalism in Buenos Aires was terminated.[citation required]

From 1829, newspapers with a unitary ideological orientation or sympathetic to the unitaries were no longer published. There were mass emigrations of journalists and men of letters to Montevideo. The entire Buenos Aires press was pro-government and supported Rosas's policies without question.

In the brief period of two years, between 1833 and 1835, most of the newspapers disappeared. In 1833 there were 43 newspapers in all. In 1835 only three remained. Among the most important newspapers closed down by the restorer were El Defensor de los Derechos Humanos, El Constitucional, El Iris, El Amigo del País, El Imparcial and El Censor Argentino.

The rosistas were in charge of opening new publications. Some of the most important newspapers of that time were El Torito de los muchachos, El Torito del Once, Nuevo Tribuno, El Diario de la Tarde, El Restaurador de las Leyes, El Lucero and El Monitor, all of them strongly rosistas, dedicated to exalting the figure of the Restorer of the Laws, and criticize the unitaries.

The Generation of '37

In 1837 a group of young intellectuals arose that began to meet in Marcos Sastre's bookstore. Among them were Esteban Echeverría, Juan Bautista Alberdi, Juan María Gutiérrez, José Mármol and Vicente Fidel López. His thought was identified with the political class that had led the independence process until the unitary organization of 1824 and adhered to the ideas of European romanticism and liberal democracy.

This group achieved some influence from two institutions: the Salón Literario, closed by order of Rosas, and La Joven Argentina, a secret society founded by Echeverría in 1838.

These young people, members of the second Creole generation, tried to be an alternative to the federal and unitary forces. They propitiated a mixed national organization, the modification of social customs and the need to have a national literature. Both his ideas and his actions had a great influence on the national organization and the constitutional process after the fall of Rosas. Some revisionist historians accuse them of considering everything European superior to what is American or Spanish, of wanting to transplant Europe to America without considering the Americans, and of siding with foreign enemies of their government, betraying it.

All of them spoke out against Rosas's policies and regarding his policy against foreign powers, especially France. All of them were persecuted by the Mazorca, the armed wing of the Popular Restoration Society. All of them ended up going into exile. The vast majority went to Montevideo. Others, like Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, emigrated to Santiago de Chile. In exile they were confused with the refugee opponents, the oldest of whom were the Unitarians, who had been joined by the black loins of the time of Balcarce; they would form a more or less homogeneous group, globally called "unitarians" by Rosas' supporters.

Palermo de San Benito

Meanwhile, Juan Manuel de Rosas had made progress in buying a large amount of land and property in the area known as "Bañado de Palermo" in Buenos Aires. Although the sources give various dates, it would be between 1836 and 1838 that the Governor would have started his personal project to build his new residence and fifth in this region far from the center of Buenos Aires.

Over the next ten years, Rosas undertook the ambitious and expensive project, which included not only an imposing mansion, the largest in Buenos Aires at the time, but also an artificial pond with a canal, various outbuildings, and the wooded and landscaped of an important area. Around 1848, he would have settled permanently in the ranch that he himself baptized Palermo de San Benito and also known as San Benito de Palermo, a name about which there are still various hypotheses that could not be confirmed.

The civil war of the '40

In June 1838, the government minister from Santa Fe, Domingo Cullen, arrived in Buenos Aires with the mission of obtaining a rapprochement between Rosas and the French fleet. But apparently he overstepped his orders, and negotiated with the commander of the fleet to lift the fleet for his province, in exchange for helping France against Rosas and suppressing the delegation that his province had made of foreign relations in that of Buenos Aires. But in the middle of the negotiations, Governor Estanislao López died, so Cullen fled to Santa Fe. There he was elected governor, but Rosas and Pascual Echagüe from Entre Ríos ignored him as such, with the excuse that he was Spanish. He was deposed and replaced by Juan Pablo López, brother of his predecessor.

Cullen fled to Santiago del Estero and took refuge in Governor Ibarra's house, from where he managed to organize an invasion of the province of Córdoba by opponents of Governor Manuel López. These were defeated, and Ibarra sent Cullen prisoner to Buenos Aires. Upon reaching the limit of the province of Buenos Aires, he was shot by Colonel Pedro Ramos in June 1839.

Cullen had sent his minister Manuel Leiva to negotiate with the Corrientes governor Genaro Berón de Astrada an alliance against Rosas, which the Corrientes accepted. But before the fall of Cullen, he sought support in the Uruguayan Rivera, with whom he signed an alliance treaty, which he never fulfilled. Berón de Astrada thus declared war against Buenos Aires and Entre Ríos. Governor Echagüe invaded Corrientes and destroyed the enemy army in the battle of Pago Largo, where Berón paid for the defeat with his life.

In May, with support and money from Buenos Aires, Echagüe invaded Uruguay, with the support of a large number of "white" soldiers, led by Juan Antonio Lavalleja, Servando Gómez and Eugenio Garzón. He got as far as Montevideo, but was defeated in the battle of Cagancha.

The French government did not achieve much with its blockade, so it decided to finance military campaigns against Rosas, both by paying a large subsidy to the Rivera government, and to the Unitarians organized in the Argentine Commission, Directed by Valentin Alsina. They looked for a prestigious military chief to lead the revolution, and the choice fell on Lavalle, whom Alberdi convinced to lead the troops.

When Echagüe attacked Uruguay, Lavalle decided to take the opportunity to invade Entre Ríos. Since he did not get any support in that province for his crusade against Rosas, he headed for Corrientes, where Governor Ferré put him in command of his army.

The first thing Ferré did was launch the founder of provincial autonomy, Mariano Vera, against Santa Fe, but he was quickly defeated and killed.

The Revolution of the Free South

In the city of Buenos Aires itself, a movement was organized against Governor Rosas, to prevent him from being re-elected as governor of the province. The military command was assumed by Colonel Ramón Maza, son of the president of the provincial legislature, Manuel Vicente Maza. Simultaneously, in the south of the province of Buenos Aires, 200 kilometers from the city, another opposition group was organized, called the Libres del Sur, headed by ranchers alarmed by the drop in exports and for the possible loss of their rights that they had obtained over their lands due to the expiration of the emphyteusis law, since many of them, Rosas -considering them opponents- had denied the sale of their fields despite the fact that it had been sanctioned a provincial law that had provided for its alienation. They planned a revolution against the governor that quickly spread throughout the southern province. They had the support of Lavalle, who had to disembark in the bay of Samborombón.

But everything went wrong: they could not count on the help of Lavalle, who went to Entre Ríos to invade it, depriving the revolutionaries of their troops. Maza's group was also betrayed: Rosas' former friend was assassinated in his official office and his son—the military commander himself—was shot by order of Rosas in prison. The Libres del Sur, discovered, launched the insurrection but just two weeks later they were defeated by Prudencio Rosas, brother of the governor, in the battle of Chascomús. The ringleaders died in battle, others were executed or imprisoned, and some had to go into exile.

The Northern Coalition

Since Heredia's death, the Unitarians from the north had been organizing and began to control the governments of Tucumán, Salta, Jujuy, and Catamarca.

Rosas remembered that they had in their possession the weapons sent by him for the war against Bolivia, and he decided to send an emissary to take it from them before they spoke out against him. The election was one of the most serious and obvious errors in the Restorer's entire career: General Gregorio Aráoz de Lamadrid, Tucuman unitary leader of the previous decade, who upon arriving in Tucumán changed sides and joined the rebels. These spoke out against Rosas and formed the Coalition of the North, led by the Tucuman minister Marco Avellaneda. They tried to extend the alliance by seducing the governors Tomás Brizuela, from La Rioja, and Ibarra, from Santiago del Estero. Both were federal, but the first was convinced by giving him the supreme military command; Ibarra refused.

At the end of 1840, Lamadrid invaded Córdoba, where a group of liberals overthrew Manuel López. They even tried revolutions in San Luis and Mendoza, but both failed.

Lavalle campaigns

Lavalle invaded Entre Ríos and engaged Echagüe in two indecisive battles. He took refuge on the south coast of the province and embarked on the French fleet, landing in the north of the province of Buenos Aires. He dodged General Pacheco and headed for Buenos Aires, settling in Merlo, and there he waited for the city to rule in his favor.

Rosas organized his headquarters in Santos Lugares ―currently San Andrés, General San Martín District―, the same headquarters that would later become famous for the prisoners held there and for the firing squad of Camila O'Gorman. He blocked his way to the capital, while Pacheco surrounded him from the north. Meanwhile, Lavalle's army was disarming due to desertions, and the city wholeheartedly supported Rosas.

Then Lavalle backed off. All the Unitarians criticized him a lot for that decision, but he really couldn't do otherwise.

Lavalle's withdrawal led the French to sign peace with Rosas and lift the blockade. Lavalle, without naval support, occupied Santa Fe, but his army continued to dwindle. For his part, Rosas launched Pacheco in pursuit, and shortly after put Oribe in command of the federal army.

Terrorism

The month of October 1840 is known as the «month of terror» or «red October» by Argentine liberal historiography. Rosas is accused of instigating a large massacre of Unitarian supporters through his vigilante organization, La Mazorca.

The truth is that twenty people were murdered that month, of which only seven were Unitarians. The homicides were committed at night, in the street and by popular lynching or by the repression of such.

The symbols of the Unitarians, and even the colored objects identified with the Unitarians ―light blue and green―, were destroyed. The houses, the clothes, the uniforms: everything that could be colored was painted red.

On October 31, peace was signed with France and it was possible to return the police to the city. Rosas immediately announced that anyone caught breaking into a house, stealing or murdering would be put to arms. The violence stopped the same day.

Some historians extend the image of those weeks of violence to his entire government, while others maintain that this was not the case. In fact, Rosas used terror more as an idea to press consciences than to eliminate people.

For Néstor Montezanti “it cannot be said that Rosas was a terrorist ruler or that he habitually used terror as a way to maintain or consolidate himself in government. It is true that, exceptionally, on two occasions in seventeen years he used it in times of serious commotion, when the danger hung over his government and the national cause that he embodied. Even in these circumstances, the use was moderate, since most of the crimes were due to fanatical exaltations and not to instructions from the Dictator, who limited himself to opening the compression valves of social passion."

However, Rosas not only did not order the murders but also fought them, as evidenced by a notification to the heads of the security forces on April 19, 1842 —the month in which there was a strong outbreak of popular lynchings— which affirms that the governor "has viewed with the most serious and profound displeasure the scandalous murders that have been committed in recent days, which, although they have been against unitary savages, nobody, absolutely nobody is authorized for such a barbaric license". In the same he orders to patrol the city "arranging what is necessary to avoid similar murders."

For O'Donnell, the class perspective of Rosas' enemies greatly influences when it comes to determining who are the ones exercising terror:

The reputation of terrorists will be greater in the feds because their popular base made some of their victims part of the well-off class. On the other hand, the unit members killed gauchos. The execution of a Maza or an O'Gorman will not also have an impact on the capital and its newspapers on the murder of hundreds of humble soldiers after the battle of "La Tablada" by order of the unitary Peace.

End of the civil war

Lavalle withdrew towards the province of Córdoba, but upon entering it he was defeated in the battle of Quebracho Herrado, forcing him to retreat to Tucumán. There he met and separated again from Lamadrid, who marched to invade Cuyo. The leader of his vanguard, Mariano Acha (the one who had delivered Dorrego into the hands of Lavalle), defeated José Félix Aldao in the battle of Angaco, but was quickly defeated at La Chacarilla and executed shortly after. A few weeks later, Lamadrid had himself appointed governor of Mendoza, endowed with the much criticized "extraordinary powers", only to be soon defeated at Rodeo del Medio. The survivors emigrated to Chile.

Lavalle waited for Oribe in Tucumán, and there he was defeated at the battle of Famaillá, in September 1841. His ally Marco Avellaneda was executed, and Lavalle himself died in a casual shooting in San Salvador de Jujuy. His remains were taken to Potosí, where the last Unitarians from the north also took refuge.

The anti-rosistas, however, had unexpected success in Corrientes, where General Paz smashed Echagüe's army in Caaguazú. From there he invaded Entre Ríos (simultaneously with Rivera) and had himself appointed governor. A conflict with Ferré forced him to flee, leaving his forces in the hands of Rivera.

At that time, the future Italian national hero Giuseppe Garibaldi made some naval campaigns, devastating towns and villages in the Argentine and Uruguayan rivers; and although Admiral Guillermo Brown highlighted the bravery of the Italian, he considered the performance of his subordinates piratical.

In Santa Fe, Juan Pablo López went over to the opposite side after the defeat of the Northern Coalition, so Oribe returned and easily defeated him in April 1842. He took refuge next to Rivera, in eastern Entre Ríos, where Oribe defeated them at Arroyo Grande, in December 1842.

Many of the prisoners from these battles were executed by order of Oribe or Rosas. At least, for the moment, the civil war had ended in Argentina.

The Final Decade

Nineteenth-century Argentine liberal historiography, which had Bartolomé Miter and Vicente Fidel López as its greatest exponents and diffusers, usually attributes great changes and transformations to the years that followed the fall of Rosas, whose government would have been a long period of stagnation, an image derived more from ideological positions than from a careful examination of the facts[citation required].

The Customs Law of 1836 had a variable application, and was repealed and reapplied according to the needs and the blockades. The combination of both processes led to great economic growth in the interior provinces, the case of Entre Ríos being very clear, but not exclusive.

Although there was strong European immigration, its characteristics were completely different from the massive immigration after its fall. Immigrants arrived from Ireland, Spain (especially from Galicia and the Basque Country) and even from England. But they did not settle in agricultural colonies, rather they had to integrate into a society controlled by the Creoles. Many Irish and Basques dedicated themselves to raising sheep, and in a few years they managed to become owners. The exclusively bovine livestock was replaced by another, dominated by sheep, and in which the main item of exports was, increasingly, wool. This led to increased economic dependence on England, the world's main buyer of wool.

Argentine society was freed from all dissidence. Those who did not join the ruling party had to emigrate or, in many cases, were killed. In the interior of the country, the automatic adherence to Rosas was imposed by the Buenos Aires armies or by the local caudillos. Many of these had emerged as emanations of the will of Rosas, such as Nazario Benavídez in San Juan, Mariano Iturbe in Jujuy or Pablo Lucero in San Luis.

It was even the work of Rosas that Justo José de Urquiza came to power in Entre Ríos, but it was a different case: this was the most capable general on the federal side, only comparable to Pacheco. After Arroyo Grande, the most important victories had been obtained by him, with troops from Entre Ríos and some reinforcements from Buenos Aires. Second, he was a very rich man, and he took advantage of his position of power to enrich himself even more. Finally, due to his military position, Rosas was forced to turn a blind eye when the man from Entre Ríos allowed smuggling to and from Montevideo.

Religious politics

Although Rosas was a Catholic and a traditionalist in his way of thinking, during his governments relations with the Catholic Church were quite complicated, mainly because he always demanded the continuity of the Patronato de Indias over the Church in Argentina.

The governor allowed the return of the Jesuits in 1836 and returned some of their property, but he quickly had conflicts with the order since they were faithful followers of the papacy in relation to the patronage and refused to publicly support his government, a situation that finally led to an open confrontation with Rosas. For this reason, around 1840 the Jesuits ended up going into exile in Montevideo.

Rosas extended his policies to religion. In all the churches, the priests had to publicly support rosismo. They celebrated masses in gratitude for their successes and in reparation for their failures. And just as civil society was subjected to the thought and uniform practices of the Rosas regime, a similar situation occurred within the clergy itself. The intrusion was such that even the saints in the pulpits were placed with the punzón currency - the famous red ribbon that characterized Rosasism - and the portrait of Rosas was implanted on the altars, sharing the place that the Church dedicates to the saints..

Rosas tolerated Bishop Mariano Medrano, elected during the government of General Juan José Viamonte, but would not have accepted any other who did not have his approval, since he considered himself a continuator of the royalist policies of the ecclesiastical patronage that the kings of Spain.

One of the best-known facts of his government was the love affair between Camila O'Gorman (23) and the priest Ladislao Gutiérrez (24), who ran away together to start a family. Rosas was urged on by the unitary press from Montevideo and Chile.

On March 3, 1848, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento wrote:

The horrible corruption of customs has come to the extreme under the horrific tyranny of the Silver Caligula that the wicked and sacrileges priests of Buenos Aires flee with the girls of the best society, without the infamous saddle taking any action against those monstrous [sic] immoralities.Faustino Sarmiento

Governor Rosas was urged on by the federals themselves, and even by the young woman's father, Adolfo O'Gorman, and unexpectedly ordered them to be shot, which was done in the Santos Lugares camp.

On August 26, 1849, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento published an article entitled "Camila O'Gorman" in La Crónica of Montevideo, where he criticized the savagery revealed in the execution of the young woman.

Some authors affirm that no law of Argentine law or of the law inherited from Spain authorized the death penalty for the acts committed, and that Gutiérrez should be handed over to ecclesiastical justice, where as the author of the kidnapping without violence he was liable to death. penalty of confiscation of assets in accordance with the Fuero Juzgo law 1, book 3, title 3 and because he was a light cleric he should be punished with degradation and perpetual banishment. As for Camila, she was only to be sent to her own house. Other authors, on the other hand, affirm that the laws in force punished the sacrilege of robbery and scandal related to the case with the death penalty, according to Items 1 4-71, I 18-6 and VII 2-3, applicable to the case.

Martín Ruiz Moreno, in La Organización Nacional, affirmed: «It was a vulgar murder. Without trial, trial, defense, or hearing." In a letter dated March 6, 1870 addressed to Federico Terrero, Rosas stated:

No person advised me of the execution of the priest Gutiérrez and Camila O’Gorman, nor did any person speak to me or write in his favor. On the contrary, all the first people of the clergy spoke to me or wrote about this daring crime, and the urgent need for an exemplary punishment to prevent similar or similar scandals. I believed the same. And with my responsibility, I ordered the execution.

The siege of Montevideo and a new rebellion from Corrientes

After the victory at Arroyo Grande, Oribe still had a score to settle: he attacked Rivera in Uruguay, and installed himself in front of Montevideo, which he laid siege to with the support of several Argentine regiments. Supported by France, England and later Brazil, and defended by Argentine refugees and European mercenaries, Rivera made the city resist until 1851. Admiral Guillermo Brown's fleet from Buenos Aires established the blockade of the port, which would have meant the immediate fall of the city., but the Anglo-French squadron under the command of Commodore Purvis managed to move the boats away from Buenos Aires and thus maintain an open road to supply the population.

Rivera was expelled from the city, but Oribe never managed to capture it.

During all that time, the best troops from Buenos Aires remained immobilized in Uruguay. In Uruguayan history, this period is known as the Great War.

Corrientes rose again against Rosas in 1843, under the command of the brothers Joaquín and Juan Madariaga, but they were unable to spread their rebellion to other provinces.

After more than four years of resistance, the new Entre Ríos governor Justo José de Urquiza defeated them in two battles, in Laguna Limpia and in Rincón de Vences. By the end of 1847, Argentina was evenly ranked behind Rosas.

The Blood Tables

Émile de Girardin reproduced in La Presse an article from the London The Atlas dated March 1, 1845 where he stated that the Lafone & Co., concessionaire of the Montevideo Customs, commissioned the poet José Rivera Indarte to write a defamatory text against Rosas. The product of that transaction would be Blood Tables.

The contract established, according to La Presse, the payment of one penny per corpse saddled with Rosas. In Tables of Blood Rivera Indarte attributed four hundred and eighty deaths to Rosas, a figure, strictly speaking, false. The deaths of Facundo Quiroga and his entourage, Alejandro Heredia and José Benito Villafañe are included; The first were assassinated by order of the Reynafé brothers, the second by order of Marco Avellaneda, and the last by Bernardo Navarro, all of them Unitarians and enemies of Rosas. Also appearing on the list are those who died due to natural causes, many unknown under the initials NN, others presumably invented and even people who would still be alive years later. If the accusations against Rivera Indarte are true, they would have meant an income of two pounds sterling for the poet. He also accused him of being responsible for the death of 22,560 people during all the battles and combats that took place in Argentina from 1829 onwards. Current estimates of casualties produced on all belligerent sides at that time do not reach half that figure.

As a corollary to this list of murders, he added a pamphlet: It is a holy action to kill Rosas, with which he ended up distorting the supposed condemnation of the crime as a political tool: "Our opinion that it is A holy action, killing Rosas is not antisocial, but in accordance with the doctrine of legislators and moralists of all times and ages. We would consider ourselves very happy if this writing moved the heart of some strong man who, plunging a liberating dagger into the chest of Rosas, restored his lost fortune to the Río de la Plata and freed America and humanity in general from the great scandal that dishonored him»..

But he also accused Rosas of many other immoralities: tax fraud, embezzlement, having "slanderously accused his respectable mother of adultery [...] he has gone to the bed where his father lay dying to insult him", from having abandoned his wife in his last days, to have lovers from the most respectable families. He went so far as to write that "he is guilty of clumsy and scandalous incest with his daughter Manuelita whom he has corrupted." He says of Manuelita that "the candid virgin is today a bloodthirsty tomboy, who bears the disgusting stain of perdition on her forehead" and that "she has presented the salty ears of a prisoner on a plate to her guests, as a delicious delicacy."

The person in charge of taking the report to London was Florencio Varela.

Published in serials by the London Times and by Le Constitutionnel in Paris, they served to justify the Anglo-French intervention in La Plata. Robert Peel, who approved the spending of Casa Lafone, wept when reading them in the Commons rostrum asking for the intervention to be approved, and Thiers shuddered at "the savagery of those descendants of Spaniards" coupling France to the British intervention.

The Anglo-French Blockade

The Rosas government had prohibited navigation on inland rivers in order to reinforce the Buenos Aires Customs, the only point through which foreign trade was carried out. For a long time, England had claimed free navigation on the Paraná and Uruguay rivers in order to sell its products. To a certain extent, this would have caused the destruction of small local production.

Due to this dispute, on September 18, 1845, the English and French fleets blocked the port of Buenos Aires and prevented the Buenos Aires fleet from supporting Oribe in Montevideo. In fact, Admiral Guillermo Brown's squadron was captured by the British fleet. One of the fundamental political objectives of the blockade was to prevent the young Eastern State from falling into the hands of Rosas and remaining fully under Argentine sovereignty.

The combined fleet advanced up the Paraná River, trying to make contact with the rebel government of Corrientes and with Paraguay, whose new president, Carlos Antonio López, intended to break somewhat of the closed regime inherited from Dr. Francia. They managed to overcome the strong defense made by Rosas' troops, led by his brother-in-law Lucio Norberto Mansilla in the battle of the Vuelta de Obligado, but months later they were defeated in the battle of Quebracho. Those battles made the previous triumph too costly, so such an adventure was not attempted again.

Upon hearing the news about the defense of Argentine sovereignty in La Plata, General José de San Martín, who lived in France, wrote:

Above all, it has for me General Rosas who has been able to defend with all energy and on all occasions the national pavilion. For this reason, after the battle of Obligado, I was tempted to send him the sword with which I contributed to defend American independence, by that act of bury, in which, with four cannons, he made known to the Anglo-French squad, that few or many, without counting the elements, the Argentines always know to defend their independence.José de San Martín