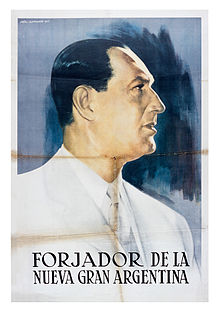

Juan Domingo Peron

Juan Domingo Perón (Lobos, October 8, 1895-Olivos, July 1, 1974) was an Argentine politician, soldier and writer, three times president of the Argentine Nation, once de facto vice president, and founder of Peronism, one of the most important popular movements in the history of Argentina. He was the only person to be elected president of his country three times and the first to be elected by universal male and female suffrage.

He participated in the Revolution of 1943, which ended the so-called Infamous Decade. After establishing an alliance with the socialist and revolutionary syndicalist union currents, he held the title of the National Department of Labor, the Secretariat of Labor and Welfare, the Ministry of War and the vice-presidency of the Nation. From the first two posts, he took measures to favor the worker sectors and make labor laws effective: he promoted collective agreements, the Peón de Campo Statute, labor courts, and the extension of retirement benefits to business employees. These measures won him the support of a large part of the labor movement and the repudiation of the business sectors, high incomes and the United States ambassador, Spruille Braden, for which reason a broad movement against him was generated from 1945. In October of that year, a military palace coup forced him to resign and then ordered his arrest, which triggered, on October 17, 1945, a great worker mobilization that demanded his release until he obtained it.. That same year he married María Eva Duarte, who played an important political role during the Perón presidency.

He ran for president in the 1946 elections and was a winner. Some time later he merged the three parties that had supported his candidacy to create first the Single Party of the Revolution and then the Peronist Party; after the Constitutional Reform of 1949, he was re-elected in 1951 in the first elections held with the participation of women and men in Argentina. In addition to continuing with his policies in favor of the most neglected sectors, his government was characterized by implementing a nationalist and industrialist line, especially with regard to the textile, steel, military, transportation, and foreign trade industries. In international politics, he held a third position before the Soviet Union and the United States, in the framework of the Cold War. In the last year of his government, he clashed with the Catholic Church, increasing the confrontation between Peronists and anti-Peronists, for which the Government hardened its persecution of the opposition and the opposition media. After a series of acts of violence by anti-Peronist civilian and military groups, and especially the bombing of the Plaza de Mayo in mid-1955, Perón was overthrown in September of that same year.

The subsequent dictatorship banned Peronism from political life and repealed the constitutional reform, which included measures to protect the lowest social sectors and the legal equality of men and women. After his overthrow, Perón went into exile in Paraguay, Panama, Nicaragua, Venezuela, the Dominican Republic and finally in Spain. Widowed since 1952, during his exile he married María Estela Martínez, known as Isabel. In his absence, a movement known as the Peronist resistance arose in Argentina, made up of various union, youth, student, neighborhood, religious, cultural and guerrilla groups, whose common goal was the return of Perón and the call for free elections. and without bans.

He tried to return to the country in 1964, but President Arturo Illía prevented him by asking the ruling military dictatorship in Brazil to arrest him and send him back to Spain. He finally returned to the country in 1972 to settle permanently in 1973. With Perón still outlawed, Peronism won the elections in March 1973, opening the period known as third Peronism. Internal sectors of the movement clashed politically and through acts of violence: after the so-called Ezeiza massacre, Perón gave broad support to the "orthodox" sectors of his party, some of which in turn created the vigilante command known as the Triple A, designed to persecute and assassinate qualified "left" militants, Peronists and non-Peronists. A month and a half after taking office, President Cámpora resigned and new elections were called without proscriptions. Perón appeared together with his wife as candidates for president and vice president respectively in September 1973 and achieved a wide victory, assuming the Government in October of that same year. He died in mid-1974, leaving the Presidency in the hands of the vice president, who was overthrown without having finished his term. Peronism continued to exist and has achieved several electoral victories.

Family history

Juan Domingo Perón was born at the end of the 19th century in the town of Lobos, Province of Buenos Aires as a "natural child", because his mother and father were not married at the time of his birth, which they did later.

Due to the documentary insufficiencies of the time and the high degree of miscegenation in Argentine society, the family and ethnic background of Juan Domingo Perón, as well as the date and precise place of his birth, have been subject to historical debate. In the year 2000, Hipólito Barreiro published his research on the birth and childhood of Perón in a book entitled Juancito Sosa: the Indian who changed history , while in 2010 and 2011 the historian lawyer Ignacio Cloppet published his on the related genealogical records of Perón and Eva Duarte, tracing them in some cases back hundreds of years. The two investigations do not seem to be mutually exclusive, since Barreiro's focuses on facts not officially registered and Cloppet's on the official records.

Father, mother and siblings

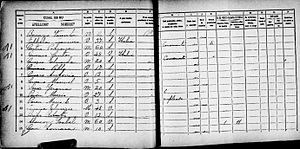

9. Sosa Juana, m [woman], 20 [years], s [sole], no [read and write];

10. Perón Mario, v [varón], 27 [years], s [soltero], employee, yes [you know how to read and write];

11. Perón Mario A, v [varón], 3 [years], s [soltero].

Her father was Mario Tomás Perón (1867-1928), an Argentine born in Lobos (Buenos Aires province) who worked as a justice officer. Her mother was Juana Salvadora Sosa (1874-1953), an Argentine Tehuelche born in the Lobos area (Buenos Aires province).She had her first child, Mario Avelino, at the age of 17, when she was still a child. single woman. They both had three children together without being married:

- Mario Avelino Perón (Lobos, November 30, 1891-Sarandí, January 13, 1955).

- Juan Domingo Perón (Lobos, October 8, 1895-Vicente López, July 1, 1974), treated here.

- Alberto Perón (n. 1899), died when he was a baby.

Juan Domingo was registered with that name on October 8, 1895 in the civil registry of Lobos by his father and his birth certificate indicates that he had been born the day before and was "natural son of the declarant", without mentioning the mother's name. In 1898 he was baptized in the Catholic Church without indicating the name of his father and being registered under the name of Juan Domingo Sosa. Juan Domingo's mother and father were married in Buenos Aires on September 25, 1901.

Paternal branch

His paternal grandparents were Tomás Liberato Perón (1839-1889), a doctor born in Buenos Aires who served as a Mitrista provincial deputy, professor of chemistry and legal medicine, member of the Public Hygiene Council, and advisor to the Faculty of Physical-Natural Sciences from the University of Buenos Aires; and Dominga Dutey Bergouignan (1844-1930), a Uruguayan born in Paysandú.

Her paternal grandfather's parents were Tomás Mario Perón (1803-1856), a Sardinian-born Genoese who arrived in Argentina in 1831, and Ana Hughes McKenzie (1815-1877), a London-born Briton. Her paternal grandmother's parents were Jean Dutey and Vicenta Bergouignan, both French-Basques, originally from Baigorry.

Maternal branch

His maternal grandparents were Juan Ireneo Sosa Martínez, a bricklayer born in the province of Buenos Aires, and María de las Mercedes Toledo Gaona, born in Azul (province of Buenos Aires).

Early Years

The official position established by law no. The official place of birth is Lobos, a small town in the center-north of the province of Buenos Aires, and in turn, in the center-east of the Argentine Republic, but which until shortly before its birth had been a military fort on the border line between the Provinces United States of the Río de la Plata and the territory of the Tehuelche, Ranquel and Mapuche peoples. The eventual belonging of Juan Domingo Perón to the Tehuelche people by maternal line is a matter of debate among historians.

Beyond the debates, he himself referred several times to his ethnicity in private and in public:

My grandmother told me that when Lobos was just a fort, they were already there... My immemorial grandmother was what we can well describe as a machaza woman, who knew all the secrets of the field... When the old woman used to tell that she had been captive of the Indians, I asked her, "Then Grandma... do I have Indian blood? I liked the idea, you know? And I think I actually have some Indian blood. Look at me: outgoing cheeks, abundant hair... Anyway, I own the Indian guy. And I feel proud of my Indian origin, because I think the best thing in the world is in the humble.Juan Domingo Perón, 1967, Report of the Journal 7 Days

In the year 2000, the historian Hipólito Barreiro published his research on the birth of Perón, according to which his entry in the civil registry could have been made two years after his birth and that the exact place could have been the zone of Roque Pérez, close to Lobos and Saladillo. With similar results, historians Oscar Domínguez Soler, Alberto Gómez Farías and Liliana Silva from the National University of La Matanza published their research in 2007 in the book Perón, when and where was he born?. On the contrary, and based on his registry investigations of 2010 and 2011, the lawyer Ignacio Cloppet has argued that his investigations into the legal records related to the birth of Perón indicate that he was born on October 8, 1895, in the city of Lobos. But both lines of investigation do not seem to be exclusive, since the former refers to events not officially registered, and the latter to the official records.

Juan Domingo grew up during his first five years in the rural areas of Lobos and Roque Pérez: "I am one of those who learned to ride a horse before walking," he will tell his friend and biographer Enrique Pavón Pereyra. About his mother, Juana, he says:

My mother, born and raised in the countryside, rode on horseback like any of us and intervened in the hunts and farms with the safety of the things that are dominated. It was a criolla with all the law. We saw in it the head of the house, but also the doctor, counselor and friend of all who had a need. That kind of matriarcado exercised without formulism, but quite effective; provoked respect but also affectionJuan Domingo Perón

In 1900, when Juan Domingo was five years old, the Perón-Sosa family embarked on the steamer Santa Cruz bound for the maritime coast of Argentine Patagonia, a few ranches from the surrounding area from Río Gallegos: Chaok-Aike, Kamesa-Aike and Coy-Aike, that is, at the beginning of a hamlet that was located in old Tehuelche settlements.

In 1902 they moved further north, first to the Chubut town of Cabo Raso, where their distant relatives with the surname Maupás owned property in La Masiega, and later, in February 1904, they moved to the town of Camarones, on the occasion of the appointment of Mario Tomás to serve temporarily as justice of the peace, on December 19, 1906. Shortly after they moved again, this time to the farm they owned which they called La Porteña, located in the Sierra Cuadrada, 175 km from the city of Comodoro Rivadavia, and later they founded another one called The Mallin.

Between 1904, the parents of Juan and Mario decided to send their children to live in Buenos Aires so they could begin formal studies, leaving them in the care of their paternal grandmother, Dominga Dutey, and the father's two half-sisters, Vicenta and Baldomera Martirena, who were teachers. The two children were seeing the big city for the first time and would only see their parents during the summers. The house of the children's paternal grandmother was located in the heart of the city, at 580 San Martín street. He studied first at the school that was next to his house, where his aunts were teachers, and then at various schools until completing his primary education, to later carry out polytechnic secondary studies at the International School of Olivos, directed by Professor Francisco Chelía.

Juan Domingo was called "Pocho" in his inner circle, a nickname that was later spread and was the nickname with which he was mentioned in different areas.

Marriages

Perón had three wives: on January 5, 1929, he married Aurelia Gabriela Tizón (March 18, 1902-September 10, 1938), daughter of Cipriano Tizón and Tomasa Erostarbe, who died of uterine cancer. His remains rest in the Olivos Cemetery, Buenos Aires province, in the Tizón family vault.

On October 22, 1945, he married actress Eva Duarte (1919-1952) in Junín.

According to witnesses from the time, it was precisely while he was in captivity that he thought of getting married. Once released, in an informal meeting, Eva Duarte introduced him to Fray Pedro Errecart, who surprised Perón by his ability to relate to one of his dogs that no one approached, and by the sincerity with which he said: & #34;If you don't get married through the Church, you can't be president".

According to witnesses from the time, it was precisely while he was in captivity that he thought of getting married. Once released, in an informal meeting, Eva Duarte introduced him to Fray Pedro Errecart, who surprised Perón by his ability to relate to one of his dogs that no one approached, and by the sincerity with which he said: & #34;If you don't get married through the Church, you can't be president".

Finally, on December 10, 1945, they were able to finalize the marriage with a private ceremony that was registered on page 2397 of the marriage book of the San Francisco parish. Juan Domingo Perón was 50 years old and Eva Duarte was 26. After the ceremony, the guests shared a meal with them in a large house located a few blocks from the temple.

The oldest residents of the neighborhood remember how grateful the General was to such an extent that he even proposed to build a new church on the Saavedra park property, but in the face of the priest's refusal, he allocated the funds to fix up the parish, which ended to be renovated in 1946.

Known as Evita, Eva Perón collaborated in the management of her husband with a policy of social aid and support for the political rights of women, who were granted the right to vote. On July 26, 1952, while Perón was in office for the second time, Evita died after a long fight against uterine cancer.

On November 15, 1961, he married María Estela Martínez Cartas, known as Isabelita, in Spain, who later accompanied him as vice president in the September 1973 elections and succeeded him in office to her death, until March 24, 1976, when she was overthrown by a military coup.

Juan Perón had no children, so his closest descendants were his nine nephews, children of his brother Mario Avelino and Eufemia Jáuregui: Dora Alicia, Eufemia Mercedes, María Juana (born in 1921), Mario Alberto, Olinda Argentina, Lía Vicenta, Amalia Josefa, Antonio Avelino and Tomás.

Military career

On March 1, 1911, he entered the Military College of the Nation, thanks to the scholarship obtained for him by Antonio M. Silva, a close friend of his paternal grandfather, who assisted him in his illness until his death. He graduated on December 18, 1913 as a second lieutenant in the infantry.

In 1914 he was assigned to the 12th Infantry Regiment based in Paraná, Entre Ríos, where he remained until 1919. In 1915 he rose to the rank of lieutenant.

In 1916 he publicly demonstrated a political stance for the first time. In that year, elections with universal and secret vote were held in Argentina for the first time, although only for men, in which Hipólito Yrigoyen of the Radical Civic Union won, in what is considered the first democratic government. Perón voted in that election for the first time, opting for Yrigoyen and the UCR, in an open confrontation with the conservative and oligarchic sectors organized in the Roquista-ideological National Autonomist Party, which had governed without alternation for the previous 36 years. During the radical governments (1916-1930) Perón would assume a position close to the legalist nationalist military (such as those exemplified by Enrique Mosconi or Manuel Savio), and at the same time critical of the radical government, mainly because of the worker massacre known as the Tragic Week of 1919 and what he considered "ineffectiveness" in the face of the country's serious social problems.

Now with the rank of lieutenant, he joined the 12th Infantry Regiment based in Paraná under the command of General Oliveira Cézar, who was sent in 1917 and 1919 by the Yrigoyen government to intervene militarily in the workers' strikes that were taking place in the forestry factories that the English company La Forestal had in the north of the province of Santa Fe. His position and that of other soldiers of the time was that in no case should the Army repress the strikers.

He attached great importance to sports: he practiced boxing, athletics and fencing. In 1918 he became a military and national fencing champion.He wrote several sports texts for military training. On December 31, 1919, he was promoted to the rank of first lieutenant and to captain in 1924. In 1926 he entered the Superior War College.

In those years he wrote several texts that were printed as study materials in military academies, such as Military Hygiene (1924), Military Morals (1925), Campaign of Upper Peru (1925), The Eastern Front in the World War of 1914. Strategic Studies (1928), among other works. On January 12, 1929, he obtained his diploma as a General Staff officer and on February 26 he was assigned to the Army General Staff as assistant to Colonel Francisco Fasola Castaño, deputy chief of the General Staff.

His time at the NCO School would provide him with contact with the humble aspirants and cadets of the school. During this time, Perón educated the cadets in the strictest military discipline, but he also taught them from manners of coexistence, to morality and ethics. During this stage, Perón also stood out as an athlete, being the army and national swordsman champion between 1918 and 1928, receiving widespread recognition from superiors and subordinates for the task he developed in the practice of sports.

In 1920 he was transferred to the "Sergeant Cabral" NCO School in Campo de Mayo, where he excelled as a troop instructor. Already then he distinguished himself among other colleagues for his special interest and treatment towards his men, which soon turned him into a charismatic military man. In those years he published his first works in the form of graphic contributions to the German translation of an exercise book for soldiers and some chapters of a manual intended for aspiring non-commissioned officers.

At the beginning of 1930 he was appointed substitute professor of Military History at the Escuela Superior de Guerra, and took over at the end of the year. That year the coup d'état of September 6 took place, led by General José Félix Uriburu who overthrew the constitutional president Hipólito Yrigoyen. The coup had the support of a broad spectrum that included radicals, socialists, conservatives, employer and student organizations, the judiciary, as well as the governments of the United States and the United Kingdom.

Perón did not hold any position in Uriburu's dictatorial government, but he participated marginally in the preparation of the coup as part of an autonomous group, with a "nationalist legalist" tendency, led by lieutenant colonels Bartolomé Descalzo and José María Sarobe, who criticized the "oligarchic conservative" group that surrounded Uriburu. This group intended to give the movement broad popular support and prevent the installation of a military dictatorship, which finally occurred. Perón was part of a column that peacefully evicted the Casa Rosada, where civil groups were looting and destroying.

After the coup, the military group of lieutenant colonels Descalzo and Sarobe, in which Perón participated, was dismantled by the military dictatorship, sending its members abroad or to distant positions in the interior of the country. Perón himself would be assigned to the Limits Commission, having to move to the northern border.

The Uriburu dictatorship (1930-1932) organized elections in which it outlawed Hipólito Yrigoyen and restricted the possibilities for Yrigoyenista radicalism to act, thus facilitating the electoral victory of a coalition of anti-Yrigoyenista radicals, conservatives, and socialists, called La Concordancia, who would govern in successive fraudulent electoral turns until 1943. That stage is known in Argentine history as the Infamous Decade.

On December 31, 1931, Perón was promoted to the rank of major. In 1932 he was appointed aide-de-camp to the Minister of War and published the book Notes on Military History, awarded the following year with a medal and diploma of honor in Brazil. He made new publications such as Notes on military history. Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 (1933) and Araucanian Toponymy (1935).

On January 26, 1936, he was appointed military attaché at the Argentine embassy in Chile, a position to which a few months later he added that of aeronautical attaché. He returned to Argentina at the beginning of 1938, being assigned to the General Staff of the Army.

After the death of his wife in September 1938, Perón tried to distract himself by helping his friend, Father Antonio D’Alessio, organize athletic competitions for the neighborhood children. Shortly after he undertook a trip to Patagonia. He traveled thousands of kilometers by car and returned at the beginning of 1939. The result of that trip and prolonged talks with the Mapuche chiefs Manuel Llauquín and Pedro Curruhuinca, was his Patagonian toponymy of Araucanian etymology .

At the beginning of 1939, he was sent to Italy to follow training courses in various disciplines, such as economics, mountaineering, skiing and high mountains. He also visited Germany, France, Spain, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Albania and the Soviet Union. He returned to Argentina two years later, on January 8, 1941. He gave a series of lectures on the state of the war situation in Europe ―within the framework of World War II (1939-1945)―, after which he was promoted to the rank of colonel at the end of the year.

On January 8, 1941, he was assigned to a mountain unit in the province of Mendoza, to keep him away from the Buenos Aires conspiracy foci, which had been too active since the beginning of the war and had accelerated their activities when the nature of the terminal illness of President Roberto M. Ortiz. There he published an article and instructions on the mountain commandos. On May 18, 1942, he ordered the transfers of Perón and Domingo Mercante to the Federal Capital.

In 1942 and 1943, the two main leaders of Argentina died during the infamous Decade, former president Marcelo T. de Alvear (a leader of the main popular opposition party, the Unión Cívica Radical) and former president Agustín P. Justo (a leader of the of the Armed Forces and of the parties that made up the official Concordance). The sudden absence of leaders, both in the political and military spheres, would greatly influence the military and political events that would unfold the following year, in which Perón played an increasingly important role.

On May 31, 1946, President Edelmiro Farrell reincorporated him into the Army and promoted him to brigadier general. On May 1, 1950, the National Congress approved Law 13896 by which Perón was promoted to division general ―despite the fact that he had expressed his opposition― effective December 31, 1949; the law was enacted in fact.

On October 6, 1950, he was promoted to Army General (later renamed "Lieutenant General"). On November 10, 1955, Decree Law No. 2034/ was published in the Official Gazette of the Argentine Republic. 55 -dated October 31- which formalized the sentence of the Court of Military Honor for disqualification due to a very serious offense in which he was deprived of his military rank, decorations and the right to wear a uniform. This situation was maintained until the publication of Law 20530 -approved by Congress on August 29, 1973 and promulgated on September 10- which declared the total nullity of the laws, decree laws, regulations, decrees and other provisions as of September 21, 1955 that deprived the ex-president of his assets, status and military hierarchy, the right to wear a uniform, distinctions and decorations.

Decorations and Badges

During his military career he received numerous decorations and distinctions:

- “Office of Staff” College of War

- "Distinctive Mountain Troop" (Andes Condor).

- « Military Pilot Distinctive»

Dictatorship called Revolution of 43

On June 4, 1943, there was a coup that overthrew the government of conservative President Ramón Castillo. Castillo's government was the last in a series of governments known in Argentine history as the infamous Decade, imposed by the dictatorship of General José Félix Uriburu (1930-1931) and sustained by electoral fraud. In 1943 General Arturo Rawson took office, but three days later he was in turn dismissed by General Pedro Pablo Ramírez.

Several historians link Perón to the GOU, acronym for a military lodge that could correspond to Grupo Obra de Unificación or Grupo de Oficiales Unidos, or to ATE (Association of Army Lieutenants), made up of medium and low-ranking Army officers graduation. This or these groups are credited with having had a great influence on the coup and the military government. However, several important historians, such as Rogelio García Lupo and Robert Potash, have argued that the GOU never existed as such or that if it had existed it had little power. Historian Roberto Ferrero maintains that the Farrell-Perón duo tried to form a pole "popular nationalist" that led to a democratic exit from the regime, confronting the undemocratic "elitist nationalist" sector, which had supported Ramírez as president.

Perón did not hold any position in the Rawson government or initially in the Ramírez government. On October 27, 1943, he took office as head of the National Labor Department, then a small state agency of little political importance.

Perón's beginnings in the new government: the alliance with the unions

Perón worked as the private secretary of General Edelmiro Farrell, who had been in charge of the Ministry of War since June 4, 1943. A few days after the coup, the CGT No. 2 led by the socialist sector of Francisco Pérez Leirós and Ángel Borlenghi and the communists met with the dictatorship's Minister of the Interior to offer him union support through a march to the Casa Rosada. The government rejected the offer and shortly after dissolved CGT No. 2, imprisoning several of its leaders.

In August 1943, the labor movement attempted a new rapprochement with the military dictatorship, this time as a result of an initiative by the powerful Union Ferroviaria Union of the CGT No. 1, upon learning that one of its leaders was brother of Lieutenant Colonel Domingo Mercante. Those talks prospered and little by little other union leaders joined them and at the request of Mercante, Colonel Juan Domingo Perón. Until then, the unions had played a minor role in the political life of the country and were led by four currents: socialism, revolutionary syndicalism, communism and anarchism. The two main unions were the Railway Union, led by José Domenech, and the Confederation of Commerce Employees, led by Ángel Borlenghi.

In the first meetings, characterized by mistrust, the unionists proposed to Mercante and Perón to form an alliance that would be installed in the small National Department of Labor, to promote from there the sanction and especially the effective application of labor laws demanded for a long time by the labor movement, as well as the strengthening of the unions and the Department of Labor itself. Perón's growing power and influence came from his alliance with a sector of Argentine syndicalism, mainly with the socialist and revolutionary syndicalist currents.

Based on that alliance and seconded by Mercante, Perón maneuvered within the government to have him appointed as head of the National Department of Labor, which was not very influential at the time, a fact that happened on October 27, 1943. Perón appointed union leaders in the main positions in the department and from there they launched the union plan, initially adopting a policy of pressure on companies to resolve labor conflicts through collective labor agreements. The vertiginous activity of the Department of Labor caused the growing support for his management by union leaders of all currents: socialists, revolutionary syndicalists, communists and anarchists, and in turn incorporating other socialists such as José Domenech (railroad worker), David Diskin (business employees), Alcides Montiel (brewer) and Lucio Bonilla (textile); revolutionary syndicalists from the Argentine Trade Union, such as Luis Gay (telephone) and Modesto Orozo (telephone); even some communists like René Stordeur (graphics) and Aurelio Hernández (health) and even Trotskyists like Ángel Perelman (metallurgist).

Secretary of Labor and Welfare

On November 27, 1943, a decree ―drafted by José Figuerola and Juan Atilio Bramuglia― created the Secretary of Labor and Welfare of the Nation; and appointed Perón as secretary, heading it.

The new body incorporated into its organization chart the functions of the Department of Labor and other departments, such as the National Retirement and Pension Fund, the National Directorate of Public Health and Social Assistance, the National Board to Combat Unemployment, the Chamber Rentals, among others. It reported directly to the President, so it had all the powers of a ministry; its function was to centralize all the social action of the State and monitor compliance with labor laws, for which it had regional offices throughout the country. In addition, the services and faculties of a conciliatory and arbitration nature were transferred to the Secretariat, as well as the functions of labor police, industrial hygiene services, inspection of mutual associations and those related to maritime, fluvial and port work..

As a reflection of the administrative hierarchy of the new Secretariat, Perón moved the offices of the old Department ―which were in a small building in Peru at the corner of Victoria, currently Hipólito Yrigoyen― to the headquarters of the Deliberative Council of the City of Buenos Aires.

At the end of 1943, the socialist trade unionist José Domenech, general secretary of the powerful Railway Union, proposed to Perón that he personally participate in the workers' assemblies. The first union assembly that he attended was on December 9, 1943 in the city of Rosario, where Domenech introduced him as "the First Worker of Argentina." Domenech's presentation would have historical consequences, since that title would be one of the arguments for Perón's affiliation to the new Labor Party to be accepted two years later, and would also appear as one of the most outstanding verses of the Peronist March.

Secretary of Labor, Minister of War and Vice President

In February 1944, the Farrell-Perón duo ousted Ramírez from the presidency; Perón was appointed to the strategic position of Minister of War on February 24, 1944 and the following day Farrell in the Presidency of the Nation, first temporarily and definitively as of March 9 of that year.

As Secretary of Labor, Perón carried out a remarkable work, getting the approval of labor laws that had historically been demanded by the Argentine labor movement, among them, generalization of severance pay, which had existed since 1934 for business employees, retirement for business employees, the Peón de Campo Statute, creation of labor justice, Christmas bonus, real effectiveness of the labor police, already existing, to guarantee its application, and for the first time collective bargaining, which became general as a basic regulation of the relationship between capital and labor. He also annulled the decree-law on union associations sanctioned by Ramírez in the first weeks of the dictatorship, which was criticized by the entire labor movement. [citation needed ]

Hand in hand with this activity, Perón, Mercante and the initial group of trade unionists who made the alliance (mainly the socialists Borlenghi and Bramuglia) began to organize a new trade union current that would gradually assume a laborist-nationalist identity.

During 1944, Farrell decisively promoted the labor reforms proposed by the Secretary of Labor. That year, the government called on unions and employers to negotiate collective agreements, a process that was unprecedented in the country. That year, 123 collective agreements were signed, reaching more than 1.4 million workers and employees, and the following year (1945) another 347 agreements would be signed, covering 2.2 million workers.

The Ministry of Labor and Welfare began to make the historic program of Argentine trade unionism a reality: Decree 33,302/43 was sanctioned, extending to all workers the severance pay that commercial employees already had; the Journalist Statute was sanctioned; the Polyclinic Hospital for railway workers was created; private employment agencies were prohibited and technical schools geared towards workers were created. On July 8, 1944, Perón was appointed Vice President of the Nation, maintaining the positions of Minister of War and Secretary of Labor.

On November 18, 1944, the promulgation of the Peón de Campo Statute (Decree-Law No. 28,194) sanctioned the previous month was announced, modernizing the semi-feudal situation in which rural workers still found themselves, alarming the large ranchers (latifundistas) who controlled Argentine exports. On November 30, labor courts were established, resisted by the employer sector and conservative groups. This regulation established for the first time, for the entire territory of the republic, humanitarian working conditions for non-transitory rural wage earners, including: minimum wages, Sunday rest, paid vacations, stability, hygiene conditions, and accommodation. This decree was ratified by Law 12,921 and regulated by Decree 34,147 of 1949. In this way, the bargaining power of rural unions was strengthened, established the Tambero-Mediero Statute, publicly supported and promised to maintain the mandatory reduction of the price of leases and the suspension of evictions, and transferred the National Agrarian Council to the scope of the Ministry of Labor and Welfare, from where some expropriations were carried out. Perón would maintain: "The land should not be an income asset, but a work asset."

On December 4, the retirement regime for business employees was approved, which was followed by a union demonstration in support of Perón, the first in his support and in which he spoke at a public event, organized by the socialist Ángel Borlenghi, general secretary of the union, gathering a huge crowd estimated at 200,000 people.

That same year, the National Health Directorate was created, under the Ministry of the Interior, which began to administer the Federal Aid Fund intended to compensate the imbalances in the jurisdictions in health matters, and through the Regional Delegations exercised influence on public health in the country's provinces and governments. Through resolution 30,655/44, which promoted free medical care in factories under the responsibility of the company, policies were supported for the unions to develop social security as a complement to state action, and hospital services were created under the control of the unions of the sugar, railway and glass industry, among others.

In parallel, unionization of workers increased: while in 1941 there were 356 unions with 441,412 members, in 1945 that number had increased to 969 unions with 528,523 members, mostly "new" workers, ethnically different from the immigrants of the previous decades, coming from the massive migration that was taking place from the interior of the country and neighboring countries to the cities, especially to Greater Buenos Aires. They began to be called contemptuously "morochos", "fats", "blacks", "blacks" and "little black heads" by the middle and upper classes, and also by some of the "old" industrial workers, descendants of European immigration.

The Ministry of Labor, with the support of an increasingly important sector of trade unionism, was massively reforming the culture that sustained labor relations, characterized until then by the predominance of paternalism characteristic of the ranch. An exponent of the employer sector opposed to the "Peronist" labor reforms; he maintained at the time that the most serious of these was that the workers had “began to look their employers in the eye”.

In this context of cultural transformation referring to the place of workers in society, the working class was constantly expanding due to the accelerated industrialization of the country. This great socio-economic transformation was the basis of Labor nationalism that took shape between the second half of 1944 and the first half of 1945 and would adopt the name peronismo. He played a central role in the enactment of decree-law 1740/45 setting the vacation regime for industrial workers and the creation of the National Labor Court. By decree No. 33,302 of December 20, 1945, the "National Institute of Remunerations" is created, a salary increase is granted and, for the first time, the complementary annual salary or bonus is instituted. Perón represented the line of greatest openness to social problems. Through the Ministry of Labor and Welfare, created at the initiative of Perón, fundamental changes were produced aimed at establishing a stronger relationship with the labor movement, and a series of labor law reforms were sanctioned, such as the Laborer's Statute, which it established a minimum wage and sought to improve the conditions of food, housing and work of rural workers, and also established social security and retirement, which benefited 2 million people. In addition, Labor Courts were created, whose rulings, in general lines, were favorable to the workers' demands (among them, the fixing of salary improvements and the establishment of the Christmas bonus for all workers), and professional associations were recognized, with which which unionism obtained a substantial improvement in its position in the legal field. It also grants new rights such as compensation, paid vacations, licenses, prevention of work accidents, technical training, etc. Likewise, between the years 1936 and 1940, the unions had signed only 46 collective labor agreements, and only between the years 1944 and 1945 they signed more than 700. On October 2, 1945, the Professional Associations Law was enacted, by which which unions are declared entities of public good. Workers thus obtain recognition of their rights, are given legal support and have the state as their backing.

1945

1945 was one of the most significant years in the history of Argentina.

Started with the obvious intention of Farrell and Perón to set the stage for declaring war on Germany and Japan, Perón's role in this decision should be noted. On January 26, 1944, the Argentine Government had broken diplomatic relations with Germany and Japan -Italy was occupied by the allies-: "Declare the state of war between the Argentine Republic and the Empire of Japan", and only in the article 3 war was declared on Germany. On March 20, the British chargé d'affaires Alfred Noble met with Perón to stress the need for such a step. But there was opposition within the Army and public opinion was divided around declaring war or not, however, it took measures to improve its image: total cessation of trade with the Axis countries, closure of pro-Nazi publications, intervention of German companies, arrest of a significant number of Nazi spies or suspects.

Already in October of the previous year, Argentina had requested a meeting of the Pan American Union to consider a course of common action. Subsequently, Perón's alliance with the unions gradually displaced the right-wing nationalist sector that had been installed in the government since the 1943 coup: Foreign Minister Orlando L. Peluffo, Corrientes comptroller David Uriburu, and above all General Juan Sanguinetti, displaced from the crucial position of comptroller of the province of Buenos Aires which, after a brief interregnum, was assumed by Juan Atilio Bramuglia, the socialist lawyer of the Unión Ferroviaria, a member of the union sector that initiated the rapprochement of the labor movement to Peron.

In February, Perón made a secret trip to the United States to agree on the declaration of war, the end of the blockade, recognition of the Argentine government, and its adherence to the Inter-American Conference of Chapultepec, which was scheduled for February 21. February of that year. Shortly after, the right-wing nationalist Rómulo Etcheverry Boneo resigns from the Ministry of Education and is replaced by Antonio J. Benítez, a man from the Farrel-Perón group.

On March 27, at the same time as most of the Latin American countries, Argentina declared war on Germany and Japan and a week later signed the Act of Chapultepec, being empowered to participate in the San Francisco Conference that founded the United Nations on June 26, 1945, integrating the group of 51 founding countries.

Simultaneously, the government began a turn to hold elections. On January 4, Interior Minister Admiral Tessaire announced the legalization of the Communist Party. The pro-Nazi newspapers Cabildo and El Pampero were banned, and the cessation of university auditors was ordered to return to the reformist system of university autonomy, while reinstating the dismissed teachers.

Peronism and anti-Peronism

The main characteristic of the year 1945 in Argentina would be the radicalization of the political situation between Peronism and anti-Peronism, promoted to a great extent by the United States, through its ambassador, Spruille Braden. From then on, the Argentine population would be divided into two frontally confronting factions: the supporters of Perón, who were the majority in the working class, and the non-Peronists, who were the majority in the middle class (especially in Buenos Aires) and the upper class.

On May 19, Spruille Braden, the new US ambassador, arrived in Buenos Aires and would serve in the post until November of the same year. Braden was one of the owners of the mining company Braden Copper Company of Chile, a supporter of the hard imperialist policy of the "Big Stick"; He had an openly anti-union position and was opposed to the industrialization of Argentina. He had previously played a relevant role in the Chaco War between Bolivia and Paraguay, preserving the interests of Standard Oil and in Cuba (1942) operating so that break relations with Spain. He later served as the United States Undersecretary for Latin American Affairs and began working as a paid lobbyist for the United Fruit Company, promoting the coup against Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala in 1954.

According to the British ambassador, Braden had "the fixed idea that he had been chosen by Providence to overthrow the Farrell-Perón regime". From the outset, Braden began publicly organizing and coordinating the opposition, exacerbating the internal conflict. The radical historian Félix Luna says that the appearance of anti-Peronism preceded the appearance of Peronism. The Stock Exchange and the Argentine Chamber of Commerce launch Manifesto of Commerce and Industry together with 321 employer organizations, criticizing the labor policy of the Secretary of Labor, since it was creating "a climate of suspicion, provocation and rebellion, which stimulates resentment, and a permanent spirit of hostility and vindication".

The trade union movement, in which open support for Perón still did not predominate, reacted quickly in defense of the labor policy and on July 12 the CGT organized a massive act under the slogan "Against the capitalist reaction". According to Félix Luna, this was the first time that the workers began to identify themselves as "Peronistas".

Anti-Peronism adopted the flag of democracy and harshly criticized what it called anti-democratic attitudes of Peronism; For his part, he took social justice as his banner and harshly criticized the contempt for the workers of his adversaries. The student movement expressed its opposition with the slogan "no to the dictatorship of the espadrilles" and the union movement and the worker demonstrations that supported the labor laws that Perón was promoting answered "sandals yes, books no."

On September 19, 1945, the opposition appeared united in a huge demonstration of more than 200,000 people, called the Constitution and Freedom March, which headed from Congress to the Recoleta neighborhood, led by fifty opposition personalities, among them the radicals José P. Tamborini, Enrique Mosca, Ernesto Sammartino and Gabriel Oddone, the socialist Nicolás Repetto, the anti-personalist radicals José M. Cantilo and Diógenes Taboada, the conservative (PDN) Laureano Landaburu, the Christian Democrats Manuel Ordóñez and Rodolfo Martínez, the pro-communist Luis Reissig, the progressive democrat Juan José Díaz Arana, and the rector of the UBA Horacio Rivarola.

It has been said that the demonstration was mainly made up of middle and upper class people, which is historically indisputable, but this does not invalidate the historical significance of its social amplitude and its political plurality. The march had a full impact on the power of Farrell-Perón and triggered a succession of military proposals against Perón's permanence in the government that materialized on October 8, when, before an adverse vote by the officials of Campo de Mayo, who was Under the command of General Eduardo J. Ávalos -one of the leaders of the GOU-, with the support of radicalism through Amadeo Sabattini, Perón resigned from all his posts. On October 11, the United States asked Great Britain to stop buying Argentine goods for two weeks to bring about the fall of the government.

On October 12, Perón was arrested and taken to Martín García Island. At that time, the leaders of the opposition movement had the country and the government at their disposal. "Perón was a political corpse" and the government, formally presided over by Farrell, was actually in the hands of General Eduardo Ávalos, who took over as Minister of War in Perón's replacement and only wanted to hand over power to civilians as soon as possible.

Perón was replaced in the vice presidency by the Minister of Public Works, General Juan Pistarini, who kept both positions, while the head of the Navy, Rear Admiral Héctor Vernengo Lima, assumed ownership of the Ministry of the Navy. The tension reached such a point that the radical leader Amadeo Sabattini was booed by a Nazi in the Casa Radical, a gigantic civil act attacked the Círculo Militar (October 12) and a paramilitary command came to plan the assassination of Perón.

The Radical House on Tucumán street in Buenos Aires had become the center of deliberations for the opposition. But the days passed without any resolution being taken, many times going so far as to promote the bosses' revenge. Tuesday, October 16, was pay day:

When they went to collect the fortnight, the workers found that the salary of the trade fair was not paid, despite the decree signed days earlier by Perón. Panaderos and textiles were the most affected by the patronal reaction. "Go and claim Perón!" was the sarcastic answer.

Organizations such as the Buenos Aires University Federation, the Argentine University Federation and the Bar Association participated in some cases in coup and terrorist activities.

October 17

On Wednesday, October 17, 1945, there was a massive mobilization of between 300,000 (according to Félix Luna's calculations) and 500,000 people, most of them workers from very humble sectors, who occupied the Plaza de Mayo demanding freedom of Peron. The union leaders, the metallurgists Ángel Perelman and Patricio Montes de Oca, Alcides Montiel from the brewing union, Cipriano Reyes from the meat union, grassroots leaders of the CGT, who went touring the factories inciting the workers, played a decisive role in it. workers to leave work to march chanting slogans in favor of Perón through the main streets towards the center of the Federal Capital, and activists such as the Uruguayan writer Blanca Luz Brum. Previously, at dawn on the 17th, a mobilization of the workers of La Boca, Barracas, Parque Patricios and the popular neighborhoods of the west of the Federal Capital as well as the industrial zones of its surroundings. The number of workers who left Berisso, a town near La Plata, was also very important. The action was barely coordinated by some union leaders who had been agitating the previous days, and the main driving force came from those same columns that fed back into the movement as they marched.

President Edelmiro J. Farrell maintained a no-nonsense attitude. The most anti-Peronist sectors of the government, such as Admiral Vernengo Lima, proposed opening fire on the demonstrators. The new strongman of the military government, General Eduardo Ávalos, remained passive, hoping that the demonstration would dissolve on its own, and refused to mobilize the troops. Finally, faced with the forcefulness of popular pressure, they negotiated with Perón and agreed on the conditions: Perón would speak to the protesters to reassure them, he would not refer to his arrest and obtain their withdrawal and on the other hand the cabinet would resign in its entirety and Ávalos would request your retirement; Perón would also retire and would not hold any position again, but in exchange he would demand that the government call free elections for the first months of 1946.

At 11:10 p.m. Perón went out onto a balcony of the Government House and spoke to the workers as they celebrated the triumph. He announced his retirement from the Army, celebrated the "democracy party" and before asking them to return to their homes peacefully, taking care not to harm the women present, he said:

I've often attended workers' meetings. I have always felt enormous satisfaction: but since today, I will feel a true pride of Argentina, because I interpret this collective movement as the rebirth of a workers consciousness, which is the only thing that can make the homeland great and immortal... And remember workers, join and be more brothers than ever. On the brotherhood of those who work, our beautiful homeland, in the unity of all Argentines, must be lifted.Juan Domingo Perón, 17 October 1945

1946 Election

After a short period of rest, during which he married Eva Duarte in Junín (Buenos Aires province) and his friend Mercante assumed the leadership of the Ministry of Labor and Welfare, on October 22 Perón began the political campaign which would culminate in his being elected president in the elections of February 24, 1946. The Radical Civic Union sector, which supported him, formed the UCR Junta Renovadora, to which the Labor Party and the Independent Party joined; For its part, the radical organization FORJA dissolved to join the Peronist movement.

An active role in the campaign would be played by the Argentine Rural Society (SRA), with the active support of Spruille Braden, US ambassador to Argentina. During the campaign, two events occurred that profoundly affected the result: on the one hand, the discovery of an important check delivered by an employers' organization as a contribution to the Unión Democrática campaign. The second was the involvement in internal affairs of the United States Department of State ―at the request of Ambassador Braden― in the electoral campaign in favor of the Tamborini-Mosca formula.

At the same time, it came to light that Raúl Lamuraglia, a businessman, had financed the campaign of the Democratic Union, through millionaire checks from the Bank of New York that had been destined to support the National Committee of the Radical Civic Union and its candidates José Tamborini and Enrique Mosca. Later, in 1951, the businessman contributed resources to support the failed coup d'état by General Benjamín Menéndez against Perón, and in June 1955 he financed the bombing of Plaza de Mayo.

In 1945, the United States embassy led by Spruille Braden promoted the unification of the opposition in an anti-Peronist front, which included the Communist, Socialist, Radical Civic Union, Progressive Democrat, Conservative parties, the Argentine University Federation (FUA), the Rural Society (landowners), the Industrial Union (large companies), the Stock Exchange, and the opposition unions. During his brief tenure as ambassador, and using an excellent command of the Spanish language, Braden acted as a political leader of the opposition, in an evident violation of the principle of non-intervention in the internal affairs of a foreign country. In 1946, a few days before the elections, Braden promoted the publication of a report called "The Blue Book", accusing the military government, like the previous one ―the Castillo presidency― of collaborating with the Axis powers, according to documents compiled by the US State Department. In response, the political parties supporting Perón's presidential candidacy published a response book entitled "The Blue and White Book," which skillfully installed the slogan Braden or Perón.

In the middle of the electoral campaign of 1946, sectors linked to the Argentine Rural Society, the local section of the Radical Civic Union and the Liberal Party of Corrientes, planned an attempt on his life in Corrientes. On February 3, 1946, this group, before Perón's march through the streets of Goya, positioned themselves on the roofs with weapons. From a vehicle in which the Liberals Bernabé Marambio Ballesteros, Gerardo Speroni, Juan Reynoldi and Ovidio Robar were traveling, they shot people from the port who heard the news and were marching downtown to repudiate the assassination attempt..

The Democratic Union supported the Blue Book and the immediate occupation of Argentina by US-led military forces; Additionally, he demanded the legal disqualification of Perón from being a candidate. This, however, did not happen and only served to destroy the chances of victory for the Democratic Union. Perón, in turn, published the Blue and White Book and published a slogan that established a forceful dilemma, "Braden or Perón", which had a strong influence on public opinion at the time of voting.

Popular support, organized by the Labor Party and the UCR Junta Renovadora, gave Perón the presidency. In the elections of February 24, 1946, being defeated only in Córdoba, Corrientes, San Juan and San Luis, Perón prevailed with 52.84% of the votes, while Tamborini placed second, with 42.87% of the vote. votes, ten points below Peronism. In the Electoral College (there was no direct vote), Perón received 299 electoral votes against only 66 for Tamborini. The Democratic Union collapsed upon its defeat and never reunited, while Perón's allied parties were unified into the Peronist Party later that year.

Unlike the elections held during the "Infamous Decade," the elections of February 1946 were recognized as absolutely fair by the opposition leaders themselves and newspapers.

Some opposition media refused to publish the result, once the presidential elections were held. The newspaper La Prensa did not publish the news that Perón had been elected president. It took him more than a month to print the news, indirectly, publishing a quote from the New York Times that took it for granted that Perón had won the presidential election. When power was transferred, the newspaper chronicled the event without ever mentioning Perón.

First Presidency (1946-1952)

The first presidential term of Juan Domingo Perón lasted from June 4, 1946 to June 4, 1952. Among the most outstanding actions is the creation of an extensive Welfare State, centered on the creation of the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare and the Eva Perón Foundation, a broad redistribution of wealth in favor of the most neglected sectors, recognition of women's political rights, an economic policy that promoted industrialization and the nationalization of basic sectors of the economy and a foreign policy of South American alliances supported by the principle of the third position. In the same period, a constitutional reform was carried out that sanctioned the so-called Constitution of 1949.

At the party level, the three parties that had supported her candidacy ―Labor, UCR-JR and Independiente― were unified in the Peronist Party and she supported the founding of the Feminine Peronist Party in 1949.

Economic policy

During the Perón government, the import substitution policy was deepened through the development of the light industry that had been promoted since the previous decade. Perón also invested heavily in agriculture, especially in planting wheat. During this time the agricultural sector was modernized, from the development of the steel and petrochemical industry, modernization and the provision of fertilizers, pesticides and machinery were promoted, so that agricultural production and efficiency increased.

The four pillars of the first Peronist economic discourse were: «internal market», «economic nationalism», «preponderant role of the State» and «central role of industry». The State gained increasing importance as a regulator of the economy in all its markets, including that of goods, and also as a provider of services.

In 1946, with Perón already elected president, the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic was nationalized, through Decree Law 8503/46. Simultaneously, a policy of discretionary credit allocation took place, through the formation of specialized official banks: the recently created Banco de Crédito Industrial supported the activity of "industry and mining", Banco Nación did so with "agriculture and commerce”, the National Mortgage Bank financed the “housing construction”, and the National Postal Savings Bank financed the “consumer credits”. The Caja was also the body that was assigned the impulse to "capture small savings" arising from the new distributive policies.

The value of the active rate differed according to the destination of the credits and was the discretionary and sole spring of the National State. All deposits in public and private banks were nationalized. With this measure, added to the “absolute control of the monetary issue” (by virtue of the nationalization of the BCRA), the State obtained hegemony over the sources of money creation in the system. Likewise, and in return, it assumed the total guarantee of bank deposits.

The active participation of the State in economic activity, added to the distributive salary policy and the recapitalization of the industry that, more due to supply problems than regulations, had been unable to equip itself during the entire war period, put pressure on global demand, which grew at a rate disproportionately higher than supply, causing an explosive increase in imports. This fact would imply the birth of high inflation in Argentina.[citation required]

The set of measures taken clearly denotes a strong stimulus to consumption, to the detriment of savings, for this sub-period. Despite the appearance of incipient inflation, the demand for money remains high throughout the stage, although with a declining trend from 1950.

Given the lack of foreign currency, a product of the stagnation of the primary sector, with which capital goods and inputs necessary for the industrialization process were imported, in 1946 Perón nationalized foreign trade by creating the Argentine Institute for the Promotion of the Exchange (IAPI) which meant the state monopoly of foreign trade. This allowed the State to obtain resources that it used to redistribute to industry. Said intersectoral exchange from the agricultural sector to the industry caused conflicts with some agricultural employers' associations, especially the Argentine Rural Society.

In 1947, he announced a Five-Year Plan to strengthen the new industries created, and begin heavy industry (steel industry and electricity generation in San Nicolás and Jujuy). Perón affirmed that Argentina had obtained political freedom in 1810, but not economic independence. Industrialization would diversify and make the productive matrix more complex (Scalise, Iriarte, s.d) and this, in turn, would allow Argentina to transcend the role assigned in the International Division of Labor. The Plan sought to transform the socio-economic structure; reduce external vulnerability (reducing debt and nationalizing public services); improve the standard of living (through redistribution and public works in health, education and housing); accelerate industrial capitalization and develop the local financial system (to stabilize the balance of payments). Thus, the State assumes an active participation in the economy.

That same year he created the Sociedad Mixta Siderúrgica Argentina (Somisa), appointing General Manuel Savio and the company Agua y Energía Eléctrica as its head. In 1948 the State nationalized the railways, mostly owned by English capital, and created the company Ferrocarriles Argentinos. Also in 1948 he created the National Telecommunications Company (ENTel). In 1950 he created Aerolíneas Argentinas, the first Argentine aviation company.

In the area of science and technology development, the development of nuclear energy began with the creation of the National Atomic Energy Commission in 1950, with scientists such as José Antonio Balseiro and Mario Báncora, who thwarted the fraud of Ronald Richter and then they laid the foundations of the Argentine nuclear plan.

In the aeronautical sector, a great boost was given to national production through the Military Aircraft Factory, created in 1927 by the radical president Marcelo T de Alvear, highlighting the development of jet aircraft through the Pulqui Project directed by the German engineer Kurt Tank. In Europe some 750 specialist workers were hired, two teams of German designers Reimar Horten, an Italian team (in charge of Pallavecino) and the French engineer Emile Dewoitine. These teams, along with Argentine engineers and technicians, would be in charge of designing the Pulqui I and Pulqui II jet planes, the twin-engine Justicialista del Aire, later renamed I.Ae. 35 Huanquero, Horten flying wings, etc. Likewise, San Martín managed the entry into the country of an important group of professors from the Polytechnic of Turin, with whom the School of Engineering of the Argentine Air Force was created. This academic staff was also part of the faculty of the Faculty of Engineering of the University of Córdoba. Aircraft I.Ae. 22 DL advanced training, the I.Ae. 24 Bombardment and attack calquin, the I.Ae. 23 primary training fighter, the twin-engined fighter I.Ae. 30 Ñancú. Rounding out that period is the assault glider I.Ae. 25 Manque, the «El Gaucho» aviation engine, the AM-1 Tábano remote-controlled rocket and elementary instruction and civilian use aircraft: the Colibrí, the Chingolo, and the F.M.A. 20 Cattle. The realization of these aeronautical projects led to the formation of an important network of suppliers of high-quality parts, and as a consequence, the creation of the industrial park that was the basis for the subsequent development and industrial takeoff of Córdoba.

After the first three years of government, the classic phase of the import substitution process ends and the expansive phase of the economic policy supported by the growth of global demand and income redistribution concludes. The political crisis will extend until 1952, the year in which the government decides to adopt a new political-economic direction.

The political crisis that began in this period has its origins in the external sector, with the drop in imports and exports by 33%, and supported by the resounding drop in reserves that dropped to 150 million dollars when at beginning of the management had reached levels of 1500 million dollars. This scenario had a great mitigation: "The strangulation of productive capacity" result of the insufficient capitalization of the productive structure in a long period, which was added to the lower availability of goods due to the contraction in imports. In addition, it is important to highlight the fall in agricultural production in the years 1951-1952 generated by the effects of droughts.

The Government maintains its expansive monetary, fiscal, and salary policy, but the pressure of global demand on an economy with fewer goods and services available enervates inflationary pressures until, in 1951, an inflationary record is reached in our country so far this century XX. The cost of living rose 37% and wholesale prices 48%.

Education policy

Primary and secondary education

During the Peronist government, the number of students enrolled in primary and secondary schools grew at higher rates than in previous years, while in 1946 there were 2,049,737 span> students enrolled in primary schools and 217,817 in secondary schools, for the year 1955 they were 2,735,026 and 467,199 respectively.

There was access to secondary education for most of the children of the middle class and for a significant part of the upper strata of the working class, especially in commercial and technical education.

Religious teaching in primary and secondary schools that came from the presidency of Ramírez was abolished on December 16, 1954 in the context of the conflict with the Catholic Church.

One of the reasons for the irritation of the opponents was the introduction in the school textbooks of drawings, photographs and laudatory texts of Perón and Evita such as «¡Viva Perón! Perón is a good ruler. Perón and Evita love us» and other similar ones. In secondary school, the subject "Citizen Culture" was introduced, which in practice was a means of government propaganda, its protagonists and their achievements, the book La razon de mi vida by Eva Perón was mandatory in the primary and secondary level.

The faster growth of secondary school compared to the first indicates that access to secondary education occurred for most of the children of the middle class and for a significant part of the upper strata of the working class, which which is confirmed by the fact that the greatest increase occurred in commercial and technical education. In 1954, the Congress with a Peronist majority repealed religious education in public schools (but not in private ones). Congress approved the Statute for the Teaching Staff of Private Education Establishments and the Private Education Union Council, which equalized the rights of private school teachers to those enjoyed by public ones.

Regarding kindergartens, the Simini law was approved in 1946, which establishes the guidelines for preschool education for infants from three to five years of age. In 1951, the Law of Stability and Escalafón number 5651 was sanctioned, which was approved by all sectors. With regard to the teacher salary, it established that it would be determined by the budget law and that the periodic bonuses would correspond to both the holders and the substitutes. Regarding promotions, it specified that positions above first category vice director would be appointed through competitive examination. In turn, the teachers managed to integrate the teacher classification panel.

University education

In terms of university policy, during his first presidency Perón promoted measures that tended to bring the popular sectors closer to the public university. In 1948 he sent Congress a bill to create the National Workers University ―currently called UTN―, which was created by Law 13,229 and put into operation in 1952, with centers in Buenos Aires, La Plata, Bahía Blanca and Avellaneda. The objective of the Universidad Obrera was to guide it towards productive engineering with free study regimes and to facilitate access for young workers. The main measures of his government were unrestricted admission, free admission and scholarships, in order to open the University to the people, which represented a whole socio-cultural revolution for the time. The gratuity was received in decree 29337 of 1949 (Broches, 2009). During Perón's first government, the study plans were coordinated, the conditions for admission to the University were unified, 14 new universities were created, and the budget was raised from 48 million (1946) to 256 million (1950). The university free of charge allowed 49,000 students in 1946 to reach 96,000 in 1950. Exclusive dedication was established to allow professionals to investigate. In addition, for the first time, a system of scholarships for low-income students was established based on a 2% tax on salaries established in articles 87 and 107 of Law No. 13,013. This made it possible for the year 1956, Argentina to be the country with the largest number of university students in all of Latin America.

In 1949, he decreed free public university education (Decree 29.337/1949); by 1955 the number of university students tripled.

When announcing the decree, Perón declared:

The current university tariffs have been abolished since today in such a way that education is absolutely free of charge and is available to all young Argentines who wish to instruct for the good of the country.Juan Domingo Perón

During his tenure, the building for the new Faculty of Law was also built and the Faculty of Architecture and Dentistry were created, always at the University of Buenos Aires. Already in his second presidency, Perón created the National Council for Technical and Scientific Research (CONITYC), the immediate predecessor of the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET), and a new regional headquarters of the Universidad Obrera was opened in Tucumán. The creation of the Institute of Mining and Geology of the UNT in the Province of Jujuy, which would be followed by the creation of institutes in the field of arts, law, economics and scientific research. In this way, he also planned the construction of the University City in the Sierra de San Javier, whose works began in 1949. In the north, he expanded the University in the region, creating the Institute of Geology and Mining, the Institute of High Biology and the Institute of Popular Medicine, in Jujuy; the Vespucci Technical School and the Humanities Institute, in Salta; the School of Agriculture in El Zanjón, in Santiago del Estero, for example. He incorporated the Salesian Labor University into the UNT and created the University Medical Service.

After 15 years of restricted democracies and military interventions on civilian governments, in 1946 Congress enacted a new Higher Education Law that placed universities under the rules of a democracy without proscription. For this, and marking a milestone in the history of higher education legislation, Peronism issued Law No. 13 031 in 1947, called the Guardo Law, in honor of the justicialist deputy creator of its articles. This legislation put an end to the long validity of the four articles of the reduced Law No. 1597 of 1885, "Avellaneda Law", which served as the legal framework until then.

In 1949, with the intention of addressing some of the proposals of university students and incorporating advances in the law enacted in 1947 and laying the foundations for a new Law, an article was incorporated into the Argentine Constitution of 1949. In 1954, the sanctions a new Law, 14,297. It incorporates some other postulates of the University Reform, such as the definition of extension and direct student participation, this law deepens student participation in the government of the Faculties, granting them the right to vote. The National University of Tucumán underwent a profound transformation, through multiple creations and a vast regional expansion, such as the construction of the Ciudad Universitaria, on San Javier hill; the foundation of the University Gymnasium, in 1948. The creation in 194 of the Institute of Mining and Geology of the UNT in the Province of Jujuy. The construction of the University City in the Sierra de San Javier was planned, whose works began in 1949. He expanded the University in the region, creating the Institute of Geology and Mining, the Institute of High Biology and the Institute of Popular Medicine, in Jujuy; the Vespucci Technical School and the Humanities Institute, in Salta; the School of Agriculture in El Zanjón, in Santiago del Estero, for example. The Salesian University of Labor was incorporated into the UNT and created the Medical Service. In 1946, under the presidency of Perón, and due to the growing industrialization of Argentina during World War II, the National Commission for Professional Learning and Orientation (CNAOP) was created and factory-schools for the training of operators were founded. In this way, by means of Law 13,229 of the year 1948, the National Workers University (UON) was created. By 1955 it already had institutes in the federal capital, Córdoba, Mendoza, Santa Fe, Rosario, Bahía Blanca, La Plata and Tucumán. The study plans privileged specialties such as mechanical constructions, automobiles, the textile industry, and electrical installations.

Health policy

In 1946 Ramón Carrillo was appointed Secretary of Public Health and in 1949, when new ministries were created, he became minister of the area. From his position, he tried to carry out a health program that was directed towards the creation of a unified system of preventive, curative health and universal social assistance in which the State would play a leading role. Regarding health policy, he is characterized by the expansion of hospital centers and the implementation of health strategies at the national level led by the Ministry of Public Health. Carrillo decided to dedicate himself to attacking the causes of diseases from the public power within his reach. Under an ideological conception that privileged the social over individual profit, it allowed progress on levels such as infant mortality, which fell from 90 per thousand in 1943 to 56 per thousand in 1955. While tuberculosis from 130 per hundred thousand in 1946 to 36 per one hundred thousand in 1951. From the management began to comply with sanitary regulations incorporated in Argentine society such as massive vaccination campaigns and the compulsory nature of the certificate for school and to carry out procedures. Massive nationwide campaigns against yellow fever, venereal disease and other scourges were implemented. At the head of the Ministry of Health, he carried out a successful campaign to eradicate malaria, directed by doctors Carlos Alberto Alvarado and Héctor Argentino Coll; the creation of EMESTA, the first national medicine factory; and support for national laboratories through economic incentives so that the remedies are available to the entire population. During his management, almost five hundred new health establishments and hospitals were inaugurated.

The government action led to a substantial improvement in public health conditions. The period was also characterized by the constitution or consolidation of the social works of the unions, especially those with the largest number of affiliates such as the railway and banking. The number of hospital beds, which was 66,300 in 1946 (4 per 1,000 inhabitants), rose in 1954 to 131,440 (7 per 1,000 inhabitants). Campaigns were carried out to combat endemic diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis and syphilis, using on a large scale the resources of DDT for the former and penicillin for the latter, and the health policy in schools was accentuated by making vaccination compulsory in their area.. It increased the number of existing beds in the country, from 66,300 in 1946 to 132,000 in 1954. It eradicated, in only two years, endemic diseases such as malaria, with extremely aggressive campaigns. It made syphilis and venereal diseases virtually disappear. He created 234 free hospitals or polyclinics. It decreased the tuberculosis death rate from 130 per 100,000 to 36 per 100,000. It ended with epidemics like typhus and brucellosis. Drastically reduced the infant mortality rate from 90 per thousand to 56 per thousand.

In 1942 some 6.5 million inhabitants had running water supply and 4 million, sewage services, and in 1955 the beneficiaries were 10 million and 5.5 million respectively. Infant mortality, which was 80.1 per thousand in 1943, dropped to 66.5 per thousand in 1953, and life expectancy, which was 61.7 years in 1947, rose to 66.5 years in 1953.

Sports policy

During his government, sport reached a high degree of development, the Evita National Tournaments were launched, the unification in 1947 of the Argentine Sports Confederation (CAD) with the Argentine Olympic Committee (COA), the presence of hundreds of athletes abroad competing in different disciplines, the promotion of non-traditional sports, the organization of the 1950 World Cup, the 1951 Pan American Games, the state sponsorship of Juan Manuel Fangio, were the first links in a national sports policy. The pilot Juan Manuel Fangio won five world championships in Formula 1. The Argentine men's basketball team won the first World Championship and the boxer Pascual Pérez became the first Argentine world champion, beginning a long saga of champions, who would make Argentina a power in professional boxing. At the same time, Argentine pelota pelota won the two gold medals in this specialty at the first Basque Pelota World Championship, dominating the discipline from then until today. The 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games marked the greatest period of splendor of the Olympic Games for Argentina, after these games Argentina would not win so many gold medals again until the 2004 Athens Olympic Games, for 1956 the delegation presented only 28 athletes, the smallest number in the country's history and were the first games that Argentina did not win a gold medal.

Communication policy

The Perón government was the first to carry out a policy regarding the media.