Juan Boscan

Juan Boscán Almogáver or Almogávar (in Catalan Joan Boscà i Almogàver) (Barcelona, 1487-íd., September 21, 1542) was a Spanish poet and translator of the Renaissance. He is mainly known for having introduced Italianate metrics (the hendecasyllable and various stanzas such as the eighth rhyme, the tercet and the sonnet), as well as Petrarchism in Spanish poetry together with Garcilaso de la Vega. In addition, he translated into Spanish The Courtier by Baltasar de Castiglione.

Biography

From a noble family (Joan Valentí Boscán, auditor of accounts and shipyard of the Generalitat, and Violant Almogáver), he had two sisters, Violante and Leonor. His ancestors were pro-Castilians and in the first half of the XV century they supported King John II, for which he was taken to the court of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, forming part of the latter's entourage at least since 1506, and there he received excellent training from the Italian humanist Lucio Marineo Sículo, who wrote in his works that was his most advanced disciple:

- I always loved you very much, Boscan of mine, not only for the nobility of your lineage and for the great ingenuity that you are endowed, but because to none I have seen adorned with greater virtues and more dedicated to the excellent study of good letters.

Indeed, he became a left-handed Hellenist and Latinist and traces of Horace, Virgil, Ovid, Museo the Grammarian and even Euripides' Iphigenia, which he apparently translated and it has not been preserved until today. He also learned the Spanish language as a natural, in such a way that even Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo noticed only Italianisms in his prose and no Catalanisms. He later served in the court of Emperor Carlos V and Fadrique Álvarez of Toledo, II. Duke of Alba, who commissioned him to be tutor and preceptor of his grandson and successor in title, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo y Pimentel; At that time he composed numerous song lyrics, echoed by the malicious jester Francesillo de Zúñiga, and he met another great poet friend of his at court, Diego Hurtado de Mendoza; he addressed an epistle in verse that Boscán answered with another, highly praised by critics, which describes his life balanced with a Horatian aftertaste. In 1522 he took part as a soldier, together with his friend, the Toledo knight and also a poet Garcilaso de la Vega, in the attempt of the prior of San Juan Diego de Toledo to free the island of Rhodes from the Ottoman siege of Suleiman the Magnificent.; this is attested by the mention of his name in the Carlo famoso (Valencia, 1566), a chronicle in dodecasyllabic verse by Luis Zapata de Chaves about the last years of Carlos I; but, contrary to what is supposed, Menéndez Pelayo testifies that these troops did not even reach Rhodes, whose siege lasted from July 28, 1522 until it fell into the power of the Turks on January 1, 1523. For his In part, in his Eclogue II.ª, Garcilaso will describe him as «full of a wise, honest and sweet affection... / a perfect man in the upper part / of the difficult courtly art, / teacher of the humane and sweet life". In 1529 the documents mention that he was on the verge of marrying a certain Isabel Malla; in 1532 he was in the defense of Vienna. In 1536 his lance and pen companion, Garcilaso, died, and dedicates his sonnet CXXIX to him:

- Garcilaso, that in good always you aspired / and always with such force you followed him, / that in a few steps that after him you ran, / in all you reached him, / tell me: why after you did not take me / when from this mortal earth you left?, / why, as you climb up to the high that you went up, / here in this chaff you left me? / Well I think that if you could forget it

Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo denies that the name Nemoroso in Garcilaso's eclogues conceals his friend Boscán, as Luis Zapata de Chaves believed. In 1539 the Catalan gentleman finally married a cultured Valencian lady, Ana Girón de Rebolledo, from whom he will have three daughters, Violante, Mariana and Beatriz; in the Epistle of her to Mendoza he declares that with her he found her happiness.

It is very possible that the appreciation that Boscán felt for the work of the poet Ausiàs March (Valencian, like his beloved wife) was transmitted to Garcilaso, since there are reminiscences of the Levantine poet in some of the Toledo poet's compositions, although Of course there are not as many as in those of another friend of Boscán, Gutierre de Cetina. In 1526 he traveled to Granada on the occasion of the emperor's wedding to Isabella of Portugal, and during his stay there he met the nuncio of Pope Clement VII, the writer Baltasar Castiglione, and the Venetian ambassador Andrea Navagero, with whom he talked in the gardens of the Generalife was convinced to cultivate Castilian poetry in Tuscan metric.

Boscán, who had previously cultivated the conceptual and courtly lyrical cancioneril, introduced the hendecasyllabic verse (in which he had more fortune and correction than his predecessor Don Íñigo López de Mendoza, Marquis of Santillana, with his 42 sonnets dated in the Italic mode) and the Italian stanzas (sonnet, eighth real, triplet enchained and the song in rooms), as well as the poem in white hendecasyllables and the motifs and structures of Petrarchism in Castilian poetry. And, as he himself recounted, he also convinced his friends Garcilaso de la Vega and Diego Hurtado de Mendoza of this novelty; Furthermore, he wrote the manifesto for the new Italianate aesthetic of the Renaissance in the following epistle, included as a prologue to one of his volumes of poetry:

Having a day in Granada with the Navagero, dealing with him in things of wit and lyrics, he told me why he did not try in the Castilian language sonnets and other arts of troves used by the good authors of Italy: and not only did he say so lightly, but he still begged me to do it... Thus I began to tempt this kind of verse, in which I found some difficulty because I was very artificing and had many different peculiarities of ours. But I was slowly getting hot in it. But this will not suffice to pass me very forward, if Garcilaso, with his judgment - which, not only in my opinion, more in that of the whole world has been had for certain thing - will not confirm me in this my demand. And so, praised me many times this purpose and just approving me with his example, because he also wanted to take this path, it made me occupy my time in this more fundamentally.Epistle of John Boscan to the duchess of Soma

Other gentlemen, however, had a more nationalist concept of the Renaissance, such as Cristóbal de Castillejo, and kindly expressed their disagreement in satires against the new style. The novelty of the hendecasyllable, however, took root alongside the eighth syllable as the most used verse in Spanish poetry and since then the dodecasyllable, with a pounding rhythm and less flexible than that of the hendecasyllable, was pushed aside and neglected in favor of the hendecasyllable when it had to deal with important issues. Castilian poetry was thus enriched with new verses, stanzas, themes, tones and expressive resources. Furthermore, Boscán's poem Hero y Leandro was the first to deal with classic legendary and mythological themes in the new meter. On the other hand, his Epístola a Mendoza introduces in Spain the model of the moral epistle as a poetic genre imitated by Horace, where the ideal of the Stoic sage is exposed with his prudent moderation and balance.

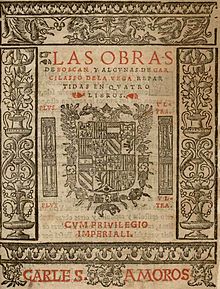

Apart from his first lyrical songbook and an extensive Petrarchan songbook in the new Italian metres, Boscán demonstrated his mastery of Spanish by translating Il libro del cortegiano (1528) by the Italian humanist Baltasar Castiglione with the title of The Courtier (1534) in exemplary Renaissance prose. The copy had been sent to him by Garcilaso de La Vega, as stated in the preliminary nuptial letter "To Gerónima Palova de Almogávar", which was followed by one from Garcilaso himself. In 1539 he left the Court and settled in Barcelona, where he prepared the edition of the works of his friend Garcilaso de la Vega along with his own. But, in 1542, on his return from a trip to Perpignan in the company of his family and the third Duke of Alba, he became seriously ill and died in Barcelona on September 21, 1542, leaving the edition unfinished, so his widow, Ana Girón de Rebolledo finished it and printed it in 1543 in the workshop of Carlos Amorós, in Barcelona, under the title The works of Boscán with some of Garcilaso de la Vega. This work includes four books, of which the first three contain the works of Boscán and the fourth those of Garcilaso. In 1546, Alonso Mudarra had already composed music for the vihuela with lyrics from poems by both, while the poet Juan de Quirós, teacher of Benito Arias Montano, imitated his style and the beginning of the poem Leandro in his Christopathy.

Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo has 21 old editions of his works, despite which, he affirms, he was not an accredited poet in the XIX century, since Manuel José Quintana did not include it in his famous anthology, nor does it appear in the equally famous Biblioteca de Autores Españoles; however, in the 19th century a notable edition was made by the American Hispanist William I. Knapp (1875) and modernly it has been edited and revalued as it deserves.

Works

- The four books of the Cortesano, composed in Italian by Count Baltasar Castellón and agora again translated in Castilian language by Boscán, Barcelona, Pedro Mompezat, 1534 (The courtier, ed. de A. M. Fabié, Madrid, Library of Bibliophiles, 1873; ed. de A. F. de Avilés, Madrid, Ibero-American Publishing Company, 1930; ed. by Ángel González Palencia, Madrid, Superior Council for Scientific Research [CSIC], 1942; ed. de T. Suero Roca, Barcelona, Bruguera, 1972; ed. de Rogelio Reyes Cano, Madrid, Espasa Calpe, 1984; ed de M. Pozzi, Barcelona, Planeta, 1994)

- The works of Boscán and some of Garcilaso distributed in four books, Barcelona, Carles Amorós, March 20, 1543 (does not include those of Juan Boscán in Liric poets from the 16th and 17th centuries, Madrid, Library of Spanish Authors, 1854); Songbook and Holy Romancer, Madrid, Library of Spanish Authors, 1872; Garcilaso and Boscan, Poetic worksed. de Enrique Díez-Canedo, Madrid, Calleja, 1917; J. Boscán, Worksed. de M. Artigas, San Sebastian, Biblioteca Nueva, 1936; Poetryed. de J. Campos, Valencia, Modern Typography, 1940; Copies, ed. de E. Nadal, Barcelona, Yunque, 1940; Martín de Riquer, Juan Boscán and his barcelonese singer, Barcelona, 1945; J. Boscán, Coplas, sonnets and other poemsed. de M. de Montoliu, Barcelona, Montaner and Simon, 1946; Poetry, ed. de M. Fernández Nieto, Barcelona, Orbis, 1983; The works of Boscán again updated [...], ed. de Carlos Clavería, Barcelona, Promotions and University Publications, Barcelona, 1993; Complete worksed. by Martin de Riquer, Antoni Comas and Joaquín Molas, Barcelona, Faculty of Philology, 1957; J. Boscán and Garcilaso de la Vega, Complete worksed. de Carlos Clavería, Madrid, Turner-Biblioteca Castro, 1995; J. Boscán, Complete worked. de Carlos Clavería, Cátedra, Madrid, 1999).