Josephus Flavius

Titus Flavius Josephus (Jerusalem, c. 37-Rome, c. 100), born Yosef ben Matityahu (Hebrew: יוסף בן מתתיהו, Greek: Ἰώσηπος Ματθίου παῖς) was a I, who was born in Jerusalem (then part of Roman Judea) to a father of priestly descent and a mother of royal descent.

He initially fought against the Romans during the First Jewish-Roman War as head of the Jewish forces in Galilee, until he surrendered in AD 67. C. to the Roman forces led by Vespasian, after a six-week siege of Jotapata. Josephus claimed that the Jewish messianic prophecies that started the first Judeo-Roman war heralded that Vespasian would become Roman emperor. In response, Vespasian decided to keep Josephus as a slave and presumably an interpreter. After Vespasian became emperor in AD 69. C., he granted Josephus his freedom, at which time Josephus assumed the surname of the Emperor Flavius.

Flavius Josephus completely defected to the Roman side and was granted Roman citizenship. He became an adviser and friend to Vespasian's son Titus, and served as a translator when Titus led the siege of Jerusalem in AD 70. As the siege proved ineffective in stopping the Jewish revolt, the destruction of the city and the looting and destruction of Herod's Temple (Second Temple) soon followed.

Josephus recorded Jewish history, with special emphasis on the I century and the first Judeo-Roman war (66- AD 70), including the siege of Masada. His most important works were The Jewish War (c. 75) and Jewish Antiquities (c. 94). The Jewish War recounts the Jewish revolt against the Roman occupation. Jewish Antiquities depicts world history from a Jewish perspective for an apparently Greek and Roman audience. These works provide valuable information about 1st century I century Judaism and the antecedents of early Christianity, although this is not specifically mentioned by Josephus. The works of Josephus are the primary source next to the Bible for the history and antiquity of ancient Palestine.

Biography

Born into one of Jerusalem's noble families, Josephus introduces himself in Greek as Iōsēpos (Ιώσηπος), the son of Matthias (Matityahu), an ethnic Jewish priest. He was the second son of him. His older brother was also named Matthias (Matityahu). His mother was an aristocratic woman descended from the formerly ruling Hasmonean royal dynasty. Josephus's paternal grandparents were Josephus (Yosef) and his wife, a Hebrew noblewoman of the whose name is unknown, distantly related to each other and direct descendants of Simon Psellus (Shimon Psellos). Josephus's family was wealthy. He was descended through his father from the priestly order of Joiarib, the first of the 24 orders of priests in the Temple of Jerusalem, from the Tribe of Levi. Josephus was a descendant through his mother of the high priest Jonathan. He was raised in Jerusalem and educated with his brother.

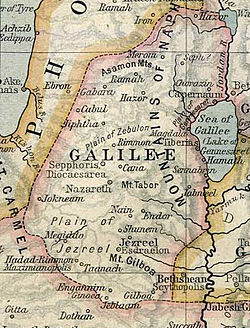

In his mid-20s, he traveled to Rome to negotiate with the Emperor Nero for the release of 12 Jewish priests. Upon his return to Jerusalem, at the outbreak of the First Judeo-Roman War, Josephus was appointed military governor of Galilee. His arrival in Galilee, however, was fraught with internal division: the inhabitants of Sepphoris and Tiberias chose to maintain peace with the Romans; the people of Sepphoris requested the help of the Roman army to protect their city, while the people of Tiberias appealed to the forces of King Agrippa to protect them from insurgents. Josephus also clashed with John of Giscala, who also intended to to take control of Galilee. Like Josephus, John rallied a large band of followers from Giscala (Gush Halab) and Gabara, with the support of the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem. Meanwhile, Josephus fortified several cities and towns in Lower Galilee, including they were Tiberias, Beersheba, Selamin, Yafa and Tarichaea, in anticipation of a Roman offensive. In Upper Galilee, he fortified the cities of Jamnia, Safed, Meron and Acabare, among other places. Josephus, with the Galileans under his command, managed to subdue both Sepphoris and Tiberias, but was eventually forced to relinquish his control over Sepphoris by the arrival of Roman forces under the tribune Placidus and later by Vespasian himself. Josephus first faced the Roman army at a village called Garis, where he launched an attack on Sepphoris a second time, before being repulsed. He eventually withstood the attacks during the siege of Yodfat (Jotapata) until he fell to the Roman army at the lunar month of Tammuz, in the thirteenth year of the reign of Nero.

After the Jewish garrison of Yodfat fell under siege, the Romans invaded and killed thousands; the survivors committed suicide. According to Josephus, he was trapped in a cave with 40 of his companions in July 67. The Romans (led by Flavius Vespasian and his son Titus, both later Roman emperors) asked the group to surrender, but they refused. Josephus suggested a method of collective suicide; they drew lots and killed each other, one by one, counting every third person. Two men remained who surrendered to Roman forces and became prisoners. In 69, Josephus was released. According to his account, he acted as a negotiator with the defenders during the siege of Jerusalem in 70, during which Simon bar Giora held his parents hostage.

While confined to Yodfat (Jotapata), Josephus claimed to have experienced a divine revelation that later led to his speech predicting that Vespasian would become emperor. After the prediction came true, he was freed by Vespasian, who considered his gift of prophecy to be divine. Josephus wrote that his revelation had taught him three things: that God, the creator of the Jewish people, had decided to "punish" them; that "fortune" had been given to the Romans; and that God had chosen him "to announce things to come". For many Jews, such claims were simply selfish.

In 71, he went to Rome in Titus' retinue, becoming a Roman citizen and client of the ruling Flavian dynasty, hence he is often called Flavius Josephus. In addition to Roman citizenship, he was granted lodging in conquered Judea and a pension. While in Rome, and under the patronage of Flavius, Josephus wrote all of his known works. Although he uses his name "Josephus", he seems to have taken the praenomen Titus and the nomen Flavius from his patron.

Vespasian arranged for Josephus to marry a captured Jewish woman, whom he later divorced. Around the year 71, Josephus married an Alexandrian Jewish woman as his third wife. They had three children, of whom only Flavio Hircano survived infancy. Josephus later divorced his third wife. Around 75, he married his fourth wife, a Greek Jewish woman from Crete, who was a member of a distinguished family. They had a happy married life and two children, Flavio Justo and Flavio Simónides Agrippa.

The life story of Josephus remains ambiguous. He was described by Harris in 1985 as a law-abiding Jew who believed in the compatibility of Judaism and Greco-Roman thought, commonly known as Hellenistic Judaism. Before the 19th century, scholar Nitsa Ben-Ari notes that his works were prohibited by to be those of a traitor, whose work was not to be studied or translated into Hebrew. His critics were never satisfied as to why he did not commit suicide in Galilee and, upon his capture, accepted Roman patronage.

Historian E. Mary Smallwood wrote critically of Josephus:

[Joseph] was attacked, not only by his own apprenticeship, but also by the opinions he had of him as commander both for the Galileans and for the Romans; he was guilty of a surprising duplicity in Jotapata, saving himself for the sacrifice of his companions; he was too naive to see how he condemned his own mouth for his conduct, and yet the words were not too harsh when he turned

Author Joseph Raymond calls Josefo "the Jewish Benedict Arnold" for betraying his own troops at Jotapata.

Importance and historical impact

The works of Josephus provide crucial information about the first Judeo-Roman war and also represent important literary material for understanding the context of the Dead Sea Scrolls and late Second Temple Judaism.

Josephus scholarship in the 19th century and early 20th century was concerned with his relationship to the sect of the Pharisees. The classical concept of Josephus portrayed him as a member of the sect and as a traitor to the Jewish nation. In the mid-20th century, a new generation of scholars challenged this view and formulated the modern concept of Josephus. he considers him a Pharisee, but his reputation as a patriot and historian of some standing is partially restored. In his 1991 book, Steve Mason argued that Josephus was not a Pharisee but an orthodox aristocrat-priest who associated with the Pharisees' school of philosophy out of deference, rather than voluntary association.

Impact on history and archeology

The works of Josephus include useful material for historians on individuals, groups, customs, and geographic locations. Josephus mentions that in his day there were 240 cities and towns scattered throughout the Upper and Lower Galilee, some of which he names. Some of the Jewish customs named by him include the practice of hanging a fine linen curtain at the entrance to their houses. houses and partaking of a Sabbath meal around the sixth hour of the day (at noon). He also notes that it was permissible for Jewish men to marry many wives (polygamy). His writings provide a significant account, extra-biblical, from the post-exilic period of the Maccabees, the Hasmonean dynasty, and the rise of Herod the Great. Describes the Sadducees, the Jewish high priests of the day, the Pharisees and the Essenes, the Herodian temple, the Quirinus census and the Zealots, and figures such as Pontius Pilate, Herod the Great, Agrippa I and Agrippa II, John the Baptist, James the brother of Jesus and Jesus (reference in Jewish Antiquities and in the Slavic version of The Jewish War ). Josephus represents an important source for the studies of Judaism of the Late Second Temple and the context of early Christianity.

A careful reading of the writings of Josephus and years of excavation allowed Ehud Netzer, an archaeologist at the Hebrew University, to discover what he considered to be the location of Herod's Tomb, after searching for 35 years. aqueducts and pools, on a flattened desert site, halfway up the hill to Herodium, 12 km south of Jerusalem, as described in the writings of Josephus. In October 2013, archaeologists Joseph Patrich and Benjamin Arubas questioned the identification of the tomb as Herod's. According to Patrich and Arubas, the tomb is too modest to be Herod's and has several unlikely features. Roi Porat, who replaced Netzer as excavation leader after the latter's death, kept the identification.

Josephus' writings provide the earliest known source for many records considered to be biblical history, despite not being found in the Bible or related material. These include Ishmael as the founder of the Arabs, the connection of "Semites", "Hamites", and "Japhethites" with the classical nations of the world, and the story of the siege of Masada.

Manuscripts, textual criticism and editions

For many years, the works of Josephus were widely known in Europe only in an imperfect Latin translation of the original Greek. Only in 1544 did a version of the standard Greek text become available in French, edited by the Dutch humanist Arnoldus Arlenius. The first English translation, by Thomas Lodge, appeared in 1602, with subsequent editions appearing throughout the 17th century. The 1544 Greek edition formed the basis of William Whiston's 1732 English translation, which achieved enormous popularity in the English-speaking world. It was often the book, after the Bible, most frequently owned by Christians. There is also an apparatus for cross-referencing Whiston's version of Josephus and the Biblical canon. Whiston claimed that certain works of Josephus were similar in style to the Pauline epistles.

Subsequent editions of the Greek text include that of Benedikt Niese, who made a detailed examination of all available manuscripts, mainly from France and Spain. Henry St. John Thackeray used Niese's version for the Loeb Classical Library edition, widely used today.

The standard editio maior of various Greek manuscripts is that of Benedictus Niese, published between 1885 and 1895. The Antiquities text is damaged in places. In the Life, Niese mainly follows the P manuscript, but also refers to AMW and R. Henry St. John Thackeray for the Loeb Classical Library, has a Greek text that also depends mainly on P. André Pelletier edited a new Greek text for his translation of the Life. The current Münsteraner Josephus-Ausgabe of the University of Münster provides a new critical apparatus. Late translations from the Greek into Old Slavonic also exist, but they contain a large number of Christian interpolations.

Audience of Josephus

Academics debate Josephus' intended audience. For example, the Jewish Antiquities could have been written for a Jewish audience: "Some scholars from Laqueur onwards have suggested that Josephus must have written primarily for Jews (if anything secondarily for Gentiles as well).. The most common reason suggested is regret: later in life he felt so badly about the treacherous war that he needed to prove [...] his loyalty to Jewish history, law and culture". However, the "innumerable Josephus's incidental remarks explaining the language, customs, and basic laws of Judea... assume a Gentile audience. He does not expect his first readers to know anything about Judean laws or origins.” The question of who would read this multi-volume work is unresolved. Other possible motives for writing Antiquities could be to dispel the misrepresentation of Jewish origins, or an apologetics to the Greek cities of the Diaspora to protect the Jews and to the Roman authorities to gain their support for the Jews who they face persecution. Neither reason explains why the intended Gentile audience would read this large body of material.

Historiography and Josephus

In the preface to The Jewish War, Josephus criticizes historians who misrepresent the events of the Judeo-Roman war, writing that they "have in mind to demonstrate the greatness of the Romans, while still the actions of the Jews dwindle and dwindle". Josephus states that he intends to correct this method, but that it "will not go to the other extreme [...] [and] will process the actions of both parties accurately". Josephus suggests that his method will not be entirely objective in saying that he will not be able to contain his lamentations when transcribing these events; to illustrate that this will have little effect on his historiography, Josephus suggests: "But if anyone is adamant in his censures against me, let him ascribe the facts to the historical part, and the lamentations only to the writer himself."

His preface to Antiquities offers his opinion at the outset, saying: "In general, a man who will examine this story, may learn chiefly from it, that all events succeed, even in a incredible degree, and the reward of happiness by God is proposed." After inserting this attitude, Josephus contradicts himself: "I will accurately describe what is contained in our records, in the order of time that pertains to them [...] without adding anything to what is contained, nor taking anything away from it". laws and historical facts, it contains so much philosophy."

In both works, Josephus emphasizes that accuracy is crucial to historiography. Louis H. Feldman notes that in The War, Josephus engages in critical historiography; but in Antiquities , Josephus switches to rhetorical historiography, which was the norm of his time.Feldman further notes that it is significant that Josephus called his later work "Antiquities" (literally, archaeology) in history place; in the Hellenistic period, archeology meant "history from the origins or archaic history". Thus, its title implies the history of a Jewish people from its origins to the time of its writing. This distinction is significant to Feldman, because "in antiquity, historians were expected to write in chronological order," while "antiquarians wrote in a systematic order, proceeding topically and logically" and included all material relevant to their analysis. subject. Antiquarians moved from political history to religious and private life and institutions. Josephus offers this broader perspective in Antiquities.

To compare his historiography with another ancient historian, consider Dionysus of Halicarnassus. Feldman enumerates these similarities: “Dionysus in praising Rome and Josephus in praising the Jews adopt the same pattern; both often moralize and psychologize and emphasize piety and the role of divine providence; and the parallels between [...] Dionysus's account of the deaths of Aeneas and Romulus and Josephus's description of the death of Moses are striking."

Work

The works of Josephus are the main sources of our understanding of Jewish life and history during the I century.

- (c. 75) The War of the Jews, The Jewish War, Jewish wars or History of the Jewish War (abbreviated commonly as JW, BJ Bell or War).

- (c. 94) Antiquities of the Jews, Jewish Antiquities or Antiquities of the Jews/Jewish Archaeology (abbreviated commonly as AJ, AotJ or Ant. or Antiq.).

- (c. 97) Flavio Josefo versus Amen, Against Apocalypse, Against Apionem or Against the Greeks, on the antiquity of the Jewish people (abbreviated commonly as CA).

- (c. 99) The Life of Flavio Josefo or Autobiography of Flavio Josefo (abbreviated) Life or Vita).

The Jewish War

His first work in Rome was an account of the Jewish war, addressed to certain "higher barbarians" (generally considered to be the Jewish community in Mesopotamia) in their "father tongue" (War I. 3), possibly the Western Aramaic language. In 78 AD C., he finished his seven-volume work in Greek known as The War of the Jews (Latin, Bellum Judaicum or De Bello Judaico ). It begins with the period of the Maccabees and concludes with the accounts of the fall of Jerusalem, and the subsequent fall of the fortresses of Herodium, Macheron and Masada and the Roman victory celebrations in Rome, the mopping up operations, the Roman military operations elsewhere in the empire and the uprising in Cyrene. Along with the account in his Life of some of the same events, he also provides the reader with an overview of Josephus's own part in the events since his return to Jerusalem from a brief visit to Rome in early from the 60s (Life 13-17).

Following the suppression of the Jewish revolt, Josephus reportedly witnessed the marches of Titus's triumphant legions leading their Jewish captives and carrying treasures from the looted Temple of Jerusalem. It was in this context that Josephus wrote his War, claiming that he was countering the accounts against Judea. He denies the claim that the Jews served a defeated God and were naturally hostile to Roman civilization. Rather, he blames The Jewish War on what he calls "unrepresentative and overzealous fanatics" among the Jews, who turned the masses away from their traditional aristocratic leaders (like himself), with results disastrous. Josephus also blames some of the Roman governors of Judea, portraying them as corrupt and incompetent administrators. According to Josephus, the traditional Jew was, should be, and can be a loyal and peace-loving citizen. Jews can, and historically have, accepted Roman hegemony precisely because their faith declares that God himself gives empires their power (Daniel 2:21).

Jewish Antiquities

Josephus's next work is his twenty-one volume work Jewish Antiquities, completed during the last year of the reign of Emperor Flavius Domitian, around AD 93 or 94. C. By exposing Jewish history, law, and customs, he entered into many current philosophical debates in Rome at the time. He again offers an apology for antiquity and the universal significance of the Jewish people. Josephus claims to be writing this history because he "saw that others perverted the truth of those actions in his writings," those writings being the history of the Jews. Of some of his sources for the project, Josephus says that he drew from and "interpreted from the Hebrew Scriptures" and that he was an eyewitness to the wars between the Jews and the Romans, which were recounted earlier in The War of the Jews.

Describes Jewish history beginning with creation, handed down through Jewish historical tradition. Abraham taught science to the Egyptians, who, in turn, taught the Greeks. Moses established a senatorial priestly aristocracy which, like that of Rome, resisted the monarchy. The great figures of the Tanakh are presented as ideal philosopher-leaders. Includes an autobiographical appendix defending his conduct at the end of the war, when he cooperated with the Roman forces.

Louis H. Feldman describes the difference between calling this work Jewish Antiquities instead of History of the Jews. Although Josephus says that he describes the events contained in Antiquities "in the order of time that pertains to them", Feldman argues that Josephus "aimed to organize [his] material systematically rather than chronologically" and had a scope that "ranged far beyond mere political history to political institutions, religious and private life".

Against Apion

Against Apion is a two-volume work that defends Judaism as a classical and philosophical religion, emphasizing its antiquity, as opposed to what Josephus claimed was the more recent tradition of the Greeks. Likewise, anti-Jewish accusations attributed by Josephus to the Greek writer Apion and the myths accredited to Manetho are refuted.

Life of Flavius Josephus

The Autobiography or Life of Flavio Josefo, the two forms in which this work is known, are titles set by critics after the author.

It is considered to have been an appendix to Jewish Antiquities. It is written in Greek, in Rome, in the final years of the life of Flavio Josefo. Ultimately, it is a plea in defense of his honor, called into question after having abandoned Israel's fight against Rome and living comfortably under the protection of the emperors of the Flavian Dynasty.

Spurious works

- Address by Josephus to the Greeks concerning Hades (date unknown); adaptation Against Plato, on the cause of the Universe of the Hippolyte of Rome.

Translations

- Flavio Josefo. The War of the Jews. Madrid: Editorial Gredos. ISBN 978-84-249-1885-9.

- Volume I: Books I–III. 1997. ISBN 978-84-249-1886-6.

- Volume II: Books IV–VII. 1999. ISBN 978-84-249-1998-6.

- - (1994). Autobiography; About the Antiquity of the Jews (Contra Apion). Translation and notes by M. Rodríguez de Sepúlveda. General introduction of L. García Iglesias. Madrid: Editorial Gredos. ISBN 978-84-249-1636-7.

- – (1987). Autobiography; About the Antiquity of the Jews (Contra Apion). Translation, introduction and notes by Ma Victoria Spottorno Díaz-Caro Autobiography and José Ramón Busto Saiz for About the antiquity of the Jews (Against Apocalypse). Madrid: Editorial Alianza. ISBN 978-84-206-6014-1.

Honors

The asteroid (6304) Josephus Flavius was named in his honor.

Further reading

- Whiston, William; Peabody, A. M., eds. (1987). The Works of Josephus, Complete and Unabridged New Updated Edition (Hardcover edition). M. A. Hendrickson Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-913573-86-8. (Josephus, Flavius (1987). The Works of Josephus, Complete and Unabridged New Updated Edition (Paperback edition). ISBN 1-56563-167-6.)

- Hillar, Marian (2005). «Flavius Josephus and His Testimony Concerning the Historical Jesus». Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism (Washington, DC: American Humanist Association) 13: 66-103.

- O'Rourke, P. J. (1993). «The 2000 Year Old Middle East Policy Expert». Give War A Chance. Vintage.

- Pastor, Jack; Stern, Pnina; Mor, Menahem, eds. (2011). Flavius Josephus: Interpretation and History. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-19126-6. ISSN 1384-2161.

- Bilde, Per. Flavius Josephus between Jerusalem and Rome: his life, his works and their importance. Sheffield: JSOT, 1988.

- Shaye J. D. Cohen. Josephus in Galilee and Rome: his vita and development as a historian. (Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition; 8). Leiden: Brill, 1979.

- Louis Feldman. "Flavius Josephus revisited: the man, his writings, and his significance." In: [Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt 21.2 (1984).

- Mason, Steve: Flavius Josephus on the Pharisees: a composition-critical study. Leiden: Brill, 1991.

- Rajak, Tessa: Josephus: the Historian and His Society. 2nd ed. London: 2002. (Oxford D.Phil. thesis, 2 vols. 1974.)

- The Josephus Trilogya novel by Lion Feuchtwanger

- Der jüdische Krieg (Josephus), 1932

- Die Söhne (The Jews of Rome), 1935

- Der Tag wird kommen (The day will come, Josephus and the Emperor), 1942

- Flavius Josephus Eyewitness to Rome's first-century conquest of Judea, Mireille Hadas-lebel, Macmillan 1993, Simon and Schuster 2001

- Josephus and the New Testament: Second Edition, by Steve Mason, Hendrickson Publishers, 2003.

- Making History: Josephus and Historical Method, edited by Zuleika Rodgers (Boston: Brill, 2007).

- Josephus, the Emperors, and the City of Rome: From Hostage to Historian, by William den Hollander (Boston: Brill, 2014).

- Josephus, the Bible, and History, edited by Louis H. Feldman and Gohei Hata (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1988).

- Josephus: The Man and the Historian, by H. St. John Thackeray (New York: Ktav Publishing House, 1967).

- A Jew Among Romans: The Life and Legacy of Flavius Josephus, by Frederic Raphael (New York: Pantheon Books, 2013).

- A Companion to Josephus, edited by Honora Chapman and Zuleika Rodgers (Oxford, 2016).

Contenido relacionado

Roberto Bolaño

Historical eruptions of Tenerife

Billy Wilder