Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (/ˈpriːstli/; 24 March (o.s. 13 March) 1733 – 6 February 1804) was a British scientist and theologian of the 19th century -variant:small-caps;text-transform:lowercase">XVIII, dissident clergyman, philosopher, educator and political theorist, who published more than 150 works. He is known as the creator of carbonated water.

He used to be considered the discoverer of oxygen, although this fact has also been attributed, with some basis, to Carl Wilhelm Scheele and Antoine Lavoisier. In any case, he was one of the first to isolate it in gaseous form, and the first to recognize its fundamental role for living organisms.

Throughout his life, Priestley had a considerable scientific reputation, residing in his invention of carbonated water, his compositions on electricity, and his discovery of multiple "airs" (gases), the most famous being what Priestley called "dephlogisticated air" (oxygen). However, his determination to defend the phlogiston theory and reject what would become the chemical revolution eventually isolated him from the scientific community.

Priestley's science was integrated into his theology, and he constantly sought to fuse Enlightenment rationalism with Christian theism. In his metaphysical texts, Priestley attempted to combine theism, materialism and determinism, a project that was called 'bold and original'. He believed that a proper understanding of the natural world would cause humans to progress and eventually achieve the Christian Millennium. Priestley, who firmly believed in the free and open exchange of ideas, advocated tolerance and equal rights for religious dissidents, which also led him to help found Unitarianism in England. The controversial nature of Priestley's publications, combined with his open support for the French Revolution, raised the suspicions of the public and the government; he was eventually forced into exile in 1791; first to London and then to the United States, after a mob burned down his Birmingham home and church. He spent his last ten years in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania.

A lifelong scholar and teacher, Priestley also made important contributions to pedagogy, including publishing seminal work on English grammar and history books, and creating some of the most influential timelines. These educational compositions were among Priestley's most popular works. It was his metaphysical works, however, that had the greatest influence: leading philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill and Herbert Spencer to credit them among the primary resources of utilitarianism.

Beginning of life and education (1733-55)

Priestley was born to a family of English dissenters (that is, Protestants who had separated from the Anglican Church, in this case Calvinists) in Hacnkey, in West Yorkshire. He was the first of six children born to Maria Swift and Jonas Priestley, a cloth merchant. To alleviate his mother's remorse, he was sent to live with his grandfather when he was one year old, and after his mother died five years later, he returned home. When his father remarried in 1741, Priesley went to live with his uncle and aunt, Sarah and John Keighley, 3 miles (4.8 km) from Fieldhead, wealthy and childless people. Because he was a precocious child - at the age of four he could flawlessly recite the 107 questions and answers of the Short Westminster Catechism (a popular Anglican catechism of the time), his aunt sought the best education for her nephew, demanding that he be an Anglican minister upon reaching adulthood. During his youth Priestley studied at local schools where he learned Greek, Latin and Hebrew.

Around 1749, Priesley became seriously ill and feared for his life. Recovering as a devotee of Calvinism, he thought a conversion experience would be necessary for his salvation, yet he doubts there would have been one. This emotional distress eventually led him to a question about theological education, which caused him to reject unconditional elections and Universalism. As a result, the elders of his house church refused to accept him as a full member.

Priesley's illness left a permanent mark on him and caused him to renounce any thoughts of entering the ministry at that time. To join a family trading business in Lisbon, he studied French, Italian and German, as well as Chaldean and Arabic. He was educated by the Reverend George Haggerstone, who first taught him advanced mathematics, natural philosophy and logic, through metaphysics and the works of Isaac Watts, Willem Gravesande and John Locke.

During his lifetime, Priestley enjoyed a considerable scientific reputation, firmly established in his invention of carbonated water, his writings on electricity and his discovery of various "airs" (gases), the most famous being what Priestley called "dephlogisticated air" (and which Scheele had called igneous air, and Lavoisier oxygen). Following his discovery of oxygen, he developed the so-called phlogiston theory, which although it was quickly demonstrated to be erroneous by Lavoisier and his followers, Priestley continued to defend with determination throughout his life. This led him to reject, at least implicitly, what would become the chemical revolution led by Lavoisier, which, linked to his radical political ideas, would seriously affect his scientific prestige at the end of his life, and would make him target of great criticism.

Priestley's conception of science was an integral part of his theology and he always sought to fuse Enlightenment rationalism with Christian theism. In his metaphysical texts, Priestley sought to combine theism, materialism and determinism, a project that has been described as "bold and original". He believed that a correct understanding of the natural world would achieve human progress and, finally, the Christian millennium would originate. One of the most Priestley's outstanding features were his scientific generosity: he firmly believed in the free and open exchange of ideas, which led him to waste the commercial potential of many of his discoveries, such as that of carbonated water. He advocated tirelessly for religious tolerance, and demanded equal rights in England for religious dissidents. His theological conceptions led him to help found Unitarianism in England. The polemical nature of Priestley's publications, combined with his open support for first the independence of the United States and later, with greater force, for the French Revolution, gave rise to both public and governmental distrust. In 1791 an angry mob stormed his Birmingham residence and burned it, forcing him to flee first to London and then to the United States, where he emigrated in 1794 at the invitation of some of the country's founding fathers. He spent the last ten years of his life living in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania.

A great scholar and teacher throughout his life, Priestley also made important contributions to pedagogy, including the publication of the foundational work of English grammar and the invention of the historiography of modern science. These educational writings were some of Priestley's most popular works; his History of Electricity continued to be used as a manual on the subject one hundred years after his death. His metaphysical work had the most lasting influence: eminent philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, and Herbert Spencer took it as a major source of utilitarianism.

Daventry Academy

Priestley finally decided to return to his theological studies and, in 1752, he enrolled at Daventry, an academy of dissenters. As he had already studied extensively, he was allowed to skip the first two years of the course. He continued the intense study of it; This, together with the liberal atmosphere of the school, united his theological thoughts with the concepts of the political left and he became a Rational Dissident. With their religious dogma and mysticism, the Rational Dissenters emphasized rational analysis of the natural world and the Bible.

Priestley wrote that the book that most influenced him, besides the Bible, was Observations on Man (1749) by David Hartley. Hartley's psychology, philosophy and theology dealt with a philosophy of the material mind. Hartley dedicated himself to building a Christian philosophy, in which both religious and moral "facts" could be scientifically proven, a goal that Priestley held for his entire life. In his third year at Daventry, he committed to participating in the ministry, which he described as "the noblest of all professions."

Needham Market and Nantwich (1755-61)

Robert Schofield, the great modern biographer who dedicated himself to studying Priestley's life and work, describes his first “call” to the parish of Dissenters in Needham Market, Suffolk, 1755, as a “deception” for both Priestley and as for the congregation. Priestley changed his simple life in favor of a more urban life with theological debates in Needham, which was a small rural village with the congregation attached to tradition. Attendance and donations to the congregation dropped sharply when the extent of his unorthodoxy was discovered. Although his aunt had promised her support when he became a minister, she refused to provide any assistance when she realized that he was nothing more than a Calvinist. To earn extra money, Priestley proposed opening a school, but local families reported that they would have to refuse to send their children. He also presented a series of scientific lectures. Among them, the conference known as “Use the Balloons” was the most successful.

Priestley's friends helped him obtain another position and, in 1758, he moved to Nantwich, Cheshire, at which time he became happier. The congregation became less bothered by his unorthodoxy and he eventually successfully established a school. Unlike many teachers of the time, Priestley taught his students natural philosophy and himself purchased scientific instruments for them. Horrified with the quality of the English grammar books available, Priestley wrote his own: “The Rudiments of English Grammar.” (1761). His innovations in describing English grammar, and particularly in disassociating it from Latin grammar, led scholars of the century to >XX to describe him as “one of the great grammarians of his time.” After the publication of Rudimentos and the success of his school, Warrington Academy offered him a position as a professor in 1761.

Warrington Academy (1761-1767)

In 1761, Priestley moved to Warrington and took up a position as professor of modern languages and rhetoric at the city's Academy of Dissenters, although he would have preferred to teach mathematics and natural philosophy. He fitted in well at Warrington and made friends quickly. On 23 June 1762 he married Mary Wilkinson of Wrexham. Of his marriage, Priestley wrote:

"The marriage showed a very proper and happy connection; my wife is a woman of excellent understanding, greatly improved the reading, of great firmness and strength of spirit, and of a temperament in the highest degree affectionate and generous; she thought a lot about others and little in herself. Apart from that, great excellence in every household thing, she has completely exempted me from all kinds of concern, which allowed me to give all my time for the progress of my studies and other duties of my stay."

On April 17, 1763, they had a daughter, whom they named Sarah Priestley in honor of Priestley's aunt.

Pedagogue and historian

All of Priestley's books that were published while he taught at Warrington emphasized the study of history; he considered that essential to the success of humanity, as well as religious growth. He wrote histories of science and Christianity, in an effort to reveal the progress of humanity and, paradoxically, the loss of a pure “primitive Christianity.”

In “Essay on a Course of Liberal Education for Civil and Active Life” (Essay on a Course of Liberal Education for a Civil and Active Life, in Spanish) (1765), "Lectures on History and General Policy", in Spanish (1788), and other works, Priestley argued that the education of young people should anticipate their future practical needs. This principle of usefulness guided unconventional curricular schools for aspiring students at Warrington Junior High School. He recommended modern languages, rather than classical languages and modern history instead of ancient history. His lessons on history were particularly revolutionary, he told a tale of providential and naturalistic history, arguing that the study of history favored the understanding of God's natural laws. Aside from that, his millenarian perspective was closely linked to his optimism regarding scientific progress and the betterment of humanity. He believed that people could improve each era from the previous one and that the study of history allowed people to perceive and advance this progress. Since the study of history was a moral imperative for Priestley, she also promoted the education of middle-class women, which was uncommon at the time. Some educational scholars describe Priestley as the most important English writer. on education between the 17th century of John Locke and the XIX by Herbert Spencer. Lectures on History (Lecciones sobre Historia, in Spanish) was well received and used by many educational institutions, such as New College in Hackney, Brown, Princeton, Yale and Cambridge. Priestley designed two charts to serve as an aid in the visual study of his Lessons. Both were popular for decades, and the Warrington tutors were so impressed with his lessons and his graphics that caused the University of Edinburgh to award him the degree of Doctor of Laws in 1764.

History of electricity

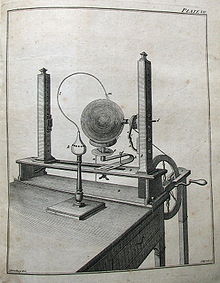

The intellectually stimulating environment of Warrington, often called the "Athens of the North" During the 18th century Priestley encouraged more interest in natural philosophy. He gave lectures on anatomy and experiments on temperature with another Warrington tutor, his friend John Seddon. Despite his busy schedule, he decided to write a book on the history of electricity. Friends introduced him to some of the UK's best experimentalists - John Canton, William Watson and the visiting Benjamin Franklin - who encouraged Priestley to carry out the experiments he wanted to include in his story. In the process of replicating the experiments, Priestley became intrigued with unanswered questions and was asked to perform the experiments in his own style. Impressed with the graphs and manuscripts of the history of electricity by Priestley, Canton, Franklin, Watson, and Richard Price, nominated Priestley for membership in the Royal Society, to which he was finally accepted in 1766.

In 1767, the 700-page “The History and Present State of Electricity” was published to positive reviews. The first half of the text is a history of the study of electricity until 1766; The second, more influential half is a description of contemporary theories of electricity and suggestions for future research. Priestley recounted some of his own discoveries in the second section, such as the conductivity of carbon and other substances and the continuity between conductors and non-conductors. This discovery disproved what he described as “one of the first and universally received maxims of electricity,” that only water and metals could conduct electricity. This and other experiments on the electrical properties of electrical materials and on the effects of chemical transformations demonstrated his continuing interest in the relationship between chemicals and electricity. Based on his experiences with modified fields, Priestley was also the first to propose that the electric force followed the inverse square law, similar to Newton's law of universal gravitation. However, he did not generalize or elaborate the proposal, and the general law was stated by the French physicist Charles-Agustín de Coulomb in the 1780s.

Priestley's strength as a natural philosopher was more qualitative than quantitative and his observation of “a true current of air” between two electrified bridges later interested Michael Faraday and James Clerck Maxwell when they investigated electromagnetism. Priestley's texts became the standard history of electricity for over a century; Alessandro Volta (who later invented the battery), WIlliam Herschel (who discovered infrared radiation) and Henry Cavendish (who discovered hydrogen) followed that text. Priestley wrote a popular version of “History of Electricity” for the general public, entitled: “A Familiar Introduction to the Study of Electricity ” (A Familiar Introduction to the Study of Electricity)(1768).

Leeds (1767-73)

Perhaps because of Mary Priestley's poor health, or financial problems, or the desire to prove his worth to the community that had rejected him in childhood, Priestley moved with his family from Warrington to Leeds, in 1767, becoming minister of Capela Mill Hill. Two sons were born to the Priestley family in Leeds: Joseph Priestley Jr on 24 July 1768 and William three years later. Theophilus Lindsey, a rector in Catterick, Yorkshire, became one of his few friends at Leeds, of whom he wrote: "I never publish anything relating to theology, without consulting it." Schofield posited that Priestley was considered a heretic by Mill Hill members. Every year Priestley traveled to London to meet his great friend and editor, Joseph Johnson, and to attend meetings of the Royal Society.

Mill Hill Chapel Minister

When Priestley became minister, Mill Hill Chapel was one of the oldest and most respected Dissident Congregations in England. However, during the 18th century the congregation had fractured along several doctrinal lines, and was losing members to the charismatic Methodist movement. Priestley believed that by educating the young, he could strengthen the bonds of the congregation.

In his masterful three-volume Institutes of Natural and Revealed Religion (1772-1774), Priestley outlined his theories of religious instruction. Most importantly, he established his belief in Socialism. The doctrines he explained would eventually become the standards for Unitarians in Britain. This work marked a shift in Priestley's theological thinking, which is critical to the understanding of his future writings, this paved the way for his materialism and necessitarianism (the belief that a divine being acts in accordance with the necessary laws of metaphysics).

Priestley's most important argument in Institutes was that the only revealed religious truths that can be accepted are those that agree with one's experience in the physical world. Because his religious position was deeply tied to his understanding of nature, the text of theism was based on theological argument. Institutes shocked and horrified many readers, mainly because it challenged Christian dogmas, such as divinity of Christ and the miracle of the Immaculate conception. Priestley wanted to return Christianity to its "primitive" or "pure", eliminating the corruptions that religion had accumulated over the centuries. The fourth part of the Institutes, a history of the Corruptions of Christianity, became so long that he was forced to publish it separately in 1782. He believed that Corruptions was 'the most valuable work'; that he published. By demanding that his readers apply the logic of the emerging sciences and compare history with the Bible and Christianity, he alienated religious and scientific readers - scientific readers did not appreciate seeing science used in the defense of religion and religious readers rejected the application of science in religion.

Controversial religious

Priestley became involved in numerous political and religious propaganda wars. According to Schofield, 'he entered into every controversy with a conviction that he was right, while most of his adversaries were convinced, from the beginning, that he was maliciously and deliberately wrong, he was able to contrast his sweet reasonableness with personal resentment towards his adversaries.” However, as Schofield noted, Priestley rarely altered his opinion as a result of these debates. While in Leeds, he wrote controversial pamphlets on the Lord's Supper and on Calvinist doctrine; Thousands of copies were published, making them Priestley's most widely read works.

Priestley founded the Theological Repository in 1768, a journal committed to the open and rational investigation of theological questions. Although he promised to print any contributions, only like-minded authors submitted his articles. Therefore, he was required to provide much of the newspaper's content (this material became the basis for many of his later theological and metaphysical works). Within a few years, due to lack of funds, he was forced to cease publication of the newspaper. He returned with the idea in 1784 with similar results.

Defender of Dissidents and political philosopher

Many of Priestley's political writings supported the repeal of the Test Act and the Corporation Act, which restricted the rights of Dissenters. They could not hold political office, serve in the armed forces, or attend Oxford and Cambridge classes unless they agreed to the Thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England. The Dissenters repeatedly asked Parliament to repeal the Acts, arguing that they were being treated as second-class citizens.

Priestley's friends, particularly other Rational Dissenters, urged him to publish a work on the injustices experienced by the Dissenters; The result was his essay on the first principles of government (1768). One of the earliest works of modern liberal political theory, and Priestley's most insightful treatment of the issue, it was one that distinguished political rights from civil rights precisely and argued for the expansion of civil rights. Priestley identified the distinction of public and private spheres, arguing that the government should only have control over the public sphere. Education and religion, in particular, were private matters of conscience and should not be administered by the State. His radicalism later arose from his conviction that the British government was infringing on these individual liberties. Priestley also defended the rights of the Dissenters against the attacks of William Blackstone, an eminent legal theorist, whose book Comments on the England's Laws (1765-1769) had become the standard legal guide. Blackstone's book stated that dissent from the Anglican Church is a crime and that Dissenters could not be loyal subjects. Priestley, furious, lashed out at Observations on Dr. Blackstone's Commentaries correcting Dr. Blackstone's interpretation of the law, its grammar (a highly politicized issue at the time), and history. Blackstone altered later editions of his commentaries: he rephrased the offending passages and replaced the sections that claimed that Dissenters could not be loyal people, but retained his description of Dissent as a crime.

Natural philosopher: electricity, optics and carbonated water

Although Priestley claimed that natural philosophy was just a hobby, he took it seriously. In History of Electricity he described the scientist as promoting “human security and happiness.” Priestley's science was eminently practical and he rarely concerned himself with theoretical questions; His model was Benjamin Franklin. When he moved to Leeds, he continued his electrical and chemical experiments (the latter aided by a stable supply of carbon dioxide from a local brewery). Between 1767 and 1770, he presented five ideas to the Royal Society based on those early experiments; The first four explored the corona effect and other phenomena related to electrical discharge, while the fifth was related to the conductivity of coal from different sources. His subsequent experimental works influenced chemistry and pneumatics.

Priestley published the first volume of his projected history of experimental philosophy, The History and Present State of Discoveries Relating to Vision, Light and Colors with Vision, Light and Colors) in 1772. He paid special attention to the history of optics and presented excellent statements of experiments, but his deficiency in mathematics caused him to ignore several important contemporary theories. Furthermore, he did not include any of the practical sections that had made his History of Electricity so useful to practical natural philosophers. Unlike History of Electricity, it was not popular and only had one edition, although it was the only book in English on the subject in 150 years. This hastily written text was a poor seller; The costs of researching, writing and editing Optics convinced Priestley to abandon his history of experimental philosophy.

Priestley was a candidate for the position of astronomer for James Cook's second South Sea voyage, but was not chosen. Still, he gave a small contribution to that voyage, teaching the crew a method of making carbonated water, which he mistakenly speculated would be a cure for scurvy. He then published a pamphlet on Directions for Impregnating Water with Fixed Air in 1772. Priestley did not explore the commercial potential of carbonated water, but others like JJ Schweppe made a fortune from it. In 1772, the Royal Society recognized Priestley's achievements in natural philosophy, awarding him the Copley Medal.

Priestley's friends wanted to find him a more financially secure position. In 1772, recommended by Richard Price and Benjamin Franklin, Lord Shelburne wrote to Priestley asking her to direct the education of his children and act as his assistant general. Although Priestley was reluctant to sacrifice his ministry, he accepted the position, resigning from Mill Hill Chapel on 20 December 1772, and giving his last sermon on 16 May 1773.

Calne (1773-80)

In 1773, the Priestleys moved to Calne, Wiltshire, and a year later Lord Shelburne and Priestley toured Europe. According to his close friend, Theophilus Lindsey, he “improved much, from the point of view of humanity in general.” Upon his return, he easily carried out his duties as bookseller and tutor.. His workload was intentionally light, leaving him time to pursue his scientific research and theological interests. Priestley also became a political advisor to Shelburne with dissidents and American interests. When his third child was born on May 24, 1777, he was named Henry at the Lord's request.

Materialist philosopher

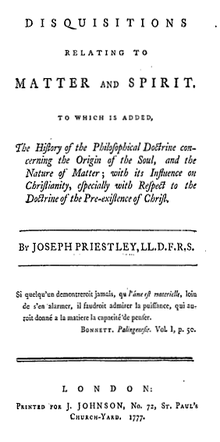

Priestley wrote his most important philosophical works during his years with Lord Shelburne. In a series of great metaphysical texts published between 1774 and 1780- An Examination of Dr. Reid's Inquiry into the Human Mind, Hartley's Theory of the Human Mind on the Principle of the Association of Ideas, Disquisitions relating to Matter and Spirit, The Doctrine of Philosophical Necessity, Letters to a Philosophical Unbeliever'- Defends a philosophy that incorporates four concepts: determinism, materialism, causality and necessitarianism. By studying the natural world, Priestley argued, people would learn to become more compassionate, happy, and prosperous.

Priestley strongly insisted on the idea that there is no mind-body dualism, and proposed a materialist philosophy in these works, that is, based on the principle that everything in the universe is composed of matter and that we can perceive it. He also maintained that arguing about the soul is impossible, because the soul is made of a divine substance and humanity cannot perceive the divine. Despite his separation between the divine and the mortal, this position shocked and outraged many of his readers, who believed that this dualism was necessary for the soul to exist.

Responding to the Système de la Nature (System of Nature)(1770) of Baron d'Holbach and the Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion) by David Hume, as well as the works of French philosophers, Priestley argued that materialism and determinism could be reconciled with a belief in God. He criticized those whose faith was shaped by books and fashion, drawing an analogy between the skepticism of the educated man and the credulity of the popular masses.

Defending that human beings do not have free will, Priestley argued that what he called “philosophical necessity” (similar to absolute determinism) is consonant with Christianity, this was a position based on his understanding of the natural world. He maintained that, just like the rest of nature, man's mind is subject to the laws of causality, but because a benevolent God created these laws, the world and people will eventually be perfected. Evil is, therefore, an imperfect understanding of the world.

Although Priestley's philosophical work was characterized as “bold and original,” he participated in ancient philosophical traditions on problems such as free will, determinism, and materialism. For example, the 17th century philosopher Baruch Spinoza also argued for absolute determinism and absolute materialism. Like Spinoza and Priestley, Leibniz argued that the human will was completely determined by natural laws. However, on the contrary, To them, Leibniz argued for an immaterial “parallel universe” of objects (such as human souls) such that organized by God, its results agree exactly with those of the material universe. Leibinz and Priestley shared an optimism of that God had benevolently chosen a chain of events; However, Priestley believed that events were moving to a glorious, Millenarian conclusion, while for Leibniz, the entire chain of events was streamlined in comparison to other conceivable chains of events.

Founder of Unitarianism

When Theophilus Lindsey decided to found a new Christian denomination that would not restrict the beliefs of its members, Priestley and others came to his aid. ON 17 April 1774, Lindsey performed Britain's first Unitarian service; he had designed his own liturgy, which was criticized by many. Priestley defended his friend in the pamphlet Letter to a Layman, on the Subject of the Rev. Mr. Lindsey's Proposal for a Reformed English Church. the Reverend Mr. Lindsey's Proposal for a Reformed English Church (1774), claiming that only the form of worship had been altered and not its essence, and attacking those who followed religion as a fashion. Priestley attended the Church of Lindsey regularly in the 1770s and occasionally preached there. He continued to support institutionalized Unitarians for the rest of his life, writing several defenses of Unitarianism and encouraging the founding of new Unitarian chapels throughout Britain. and the United States.

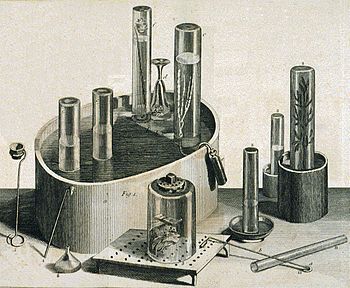

Experiments and observations in different types of air

Priestley's years at Calne were the only ones in his life dominated by scientific research, as they were also the most scientifically fruitful. His experiments were almost entirely confined to “airs,” and from that work emerged his most important scientific texts: the six volumes of Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air. Different Types of Air (1774-1786). These experiences will contribute to repudiating the last vestiges of the theory of the four elements, which Priestley tried to replace with his own variation of the phlogiston theory. According to this theory from the 18th century, the combustion or oxidation of a substance corresponds to the release of a material substance, phlogiston.

Priestley's work on “airs” is not easily classified. As the historian of science Simon Schaffer wrote that Priestley's work "has been regarded as a branch of physics, or chemistry, or natural philosophy, or an overly idiosyncratic version of Priestley's own invention." Furthermore, the volumes were at once a scientific and political effort, in which Priestley asserts that science could destroy “undue and usurped authority” and that the government had “reason to fear the very presence of an air bomb or a machine.” electric".

Volume I of Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air outlined a series of discoveries: “nitrous air” (nitrogen oxide (II), NO); “salt spirit vapor,” later called “acid air” or “acid marine air” (anidrous hydrochloric acid, HCl); “air to alkaline” (ammonia, NH3); “attenuated” or “dephlogisticated nitrous air” (nitrogen oxide (I), N2O); and, the most famous, “dephlogisticated air” (oxygen, O2), as well as the experimental results that would eventually lead to the discovery of photosynthesis. Priestley also developed a “nitrous air test” to determine the “goodness of the air.” Using a pneumatic trough, he mixed nitrous air with a test sample, over water or mercury, and measured the decrease in volume, the principle of eudiometry. After a short history of the air study, he explained his own experiences in an open and sincere style. As one novice biographer writes, "whatever he knows or thinks he says: doubts, perplexities, errors are clarified with the most refreshing candor." He also described his cheap, simple-to-assemble, experimental apparatus, his friends, for example. Therefore, they believed they could easily reproduce their experiments. Faced with inconsistent experimental results, Priestley employed the phlogiston theory. This, however, led him to conclude that there were only 3 types of “air”: “fixed”, “alkaline” and “acid”. Priestley dismissed the burgeoning chemistry of his time. Instead, he focused on gases and “changes in their sensible properties,” as natural philosophers before him did. He isolated carbon monoxide (CO), but apparently did not realize that it was a distinct “air.”

Discovery of oxygen

In August 1774 Priestley made an “air” that seemed to be entirely new, but he now had the opportunity to pursue the matter because he was about to make a trip through Europe with Shelburne. In Paris, however, he managed to reproduce the experience for others, including the French chemist Antoine Lavoisier. After returning to Britain in January 1775, he continued his experiments and discovered “acidic vitriolic air” (sulfur dioxide, SO2).

In March, he wrote to several people about the new “air” he had discovered in August. One of these letters was read aloud at the Royal Society in a paper describing the discovery, entitled "An Account of New Discoveries in the Air", which was published in the Society's journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Priestley called the new substance "dephlogisticated air", in which he made the famous experiment of focusing the sun's rays on a sample of mercury oxide. He was the first to test it on mice, which he was surprised to survive for quite a long time in a trap filled with air, and then on himself, writing that it was

"five or six times better than the common air for the effects of breathing, swelling and, I think, any other use for normal atmospheric air."

In 1778, the gas was renamed oxygen (O2) by Lavoisier.

Priestley added facts such as his discovery of oxygen and several others in a second volume of Experiments and Observations on Air (1776). He did not emphasize his discovery of "dephlogisticated air" (leaving it for the third part of the volume), but instead he argued in the preface how the discoveries were important for rational religion. His work chronicled the discovery, in chronological order, recounting the long intervals between his first experiences and his initial confusion; It is difficult to determine exactly when Priestley "discovered" oxygen. This date is important, since both Lavoisier and the Swedish pharmacist Carl Wilhelm Scheele had strong claims for the discovery of oxygen. Scheele was the first to isolate the gas (although he published after Priestley) and Lavoisier was the first to describe it as an "air of its own, unaltered" purified (i.e., the first to explain oxygen without the Phlogiston Theory).

In his article titled “Observations on Respiration and the Use of Blood,” Priestley was the first to suggest a connection between blood and air, but he did so using Phlogiston Theory. In typical Priestley fashion, he preferred the work to a study of the history of breathing. A year later, clearly influenced by Priestley, Lavoisier also discussed respiration at the Académie des sciences. Lavoisier's work began the long sequence of discoveries that produced papers on oxygen and respiration and culminated in the abandonment of Phlogiston Theory and the establishment of modern chemistry.

Around 1779 Priestley and Shelburne had a breakup; The precise reasons remain unclear. Shelburne blamed Priestley's health, while Priestley claimed that Shelburne had no new use for him. Some contemporaries speculated that Priestley's words had hurt Shelburne's political career. Schofield argued that the most likely reason for the misunderstanding was Shelburne's recent marriage to Louisa Fitzpatrick—she apparently did not like the Priestley Family. Although Priestley considered having him move to America, he finally accepted the offer of New Meeting, in Birmingham, to be his minister.

Birmingham (1780-91)

In 1780 the Priestley family moved to Birmingham and spent a happy decade, surrounded by old friends, until they were forced to flee in 1791 from a violent mob of religious fanatics. Priestley accepted a ministerial position at New Meeting on the condition that he would be required to preach and teach only on Sundays, so that he would have time to write and carry out his scientific experiments. As in Leeds, Priestley established classes for the young men of his parish and by 1781, he was teaching 150 students. As his salary was only 100 guineas, his friends and employers donated money and goods to help him continue his research. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1782.

Chemical Revolution

Many of the friends Priestley made in Birmingham were members of the Lunar Society, a group of craftsmen, inventors and natural philosophers who met monthly to discuss their work. The core of the group included men such as the manufacturer Matthew Boulton, the chemist and geologist James Keir, the inventor and engineer James Watt, and the botanist, chemist and geologist William Withering. Priestley was invited to join this unique society and contributed much to the work of its members. As a result of this intellectual environment, he published several important scientific articles, including Experiments relating to Phlogiston, and the seeming Conversion of Water into Air (Experiments related to Phlogiston and the apparent transformation of Water into Air) (1783). The first part attempts to refute Lavoisier's arguments for his work on oxygen, the second part describes how vapor is “converted” into air. After various variations of experiments, with different substances as fuel and different collecting apparatus (which produced different results), he concluded that air could travel through more substances than previously assumed, a conclusion "contrary to all principles." "This discovery, along with their earlier work in what would later be recognized as gaseous diffusion, would eventually lead John Dalton and Thomas Graham to formulate the kinetic theory of gases.

In 1777, Antoine Lavoisier had written Mémoire sur la combustion en général, the first of what proved to be a series of attacks on the phlogiston theory; it was these attacks against which Priestley he responded in 1783. While Priestley accepted parts of Lavoisier's theory, he was not prepared to admit the major revolutions that Lavoisier proposed: the elimination of phlogiston, a chemistry conceptually based on elements and compounds, and a new chemical nomenclature. Priestley's original experiments in "dephlogisticated air" (oxygen), combustion, and water provided Lavoisier with the data he needed to build much of his system, although Priestley never accepted Lavoisier's new theories and continued to defend the phlogiston theory. the rest of his life. Lavoisier's system was largely based on the quantitative concept that mass is neither created nor destroyed in chemical reactions (principle of conservation of mass). In contrast, Priestley preferred to observe qualitative changes in heat, color and particularly volume. His experiments tested “airs” for “their solubility in water, their power to withstand or extinguish the flame, whether they were breathable, how they behaved with acidic and alkaline airs, and with nitric oxide and flammable air, and finally how they were affected.” electrical sparks.

In 1789, when Lavoisier published Traité Élémentaire de Chimie and founded Annales de Chimie, the new chemistry arrived on its own. Priestley published more scientific papers in Birmingham, most attempting to refute Lavoisier. Priestley and other members of the Lunar Society argued that the new French system was too expensive, too difficult to test, and unnecessarily complex. Priestley in particular rejected the aura of “establishment.” In the end, Lavoisier's vision prevailed: his new chemistry introduced many principles on which modern chemistry is based.

Priestley's refusal to accept Lavoisier's “new chemistry” as well as the conservation of mass, and his determination to adhere to a less satisfactory theory, has surprised many scholars. Schofield explains: “Priestley was never a chemist, in a modern, and even in a Lavoisieran, sense, he was never a scientist. He was a natural philosopher, concerned with the economy of nature and obsessed with the idea of unity, in theology and in nature." Science historian John McEvoy largely agrees, writing that Priestley's view of nature as concordant with God and infinite, which led him to focus on facts over hypotheses and theories, led him to reject Lavoisier's system. McEvoy argues that “Priestley's single and isolated opposition to the oxygen theory was a measure of his passionate concern for the principles of intellectual freedom, epistemological equality and critical inquiry.” Priestley himself claimed in the last volume of Experiments and Observations that his most valuable works were his theological works because they were “superior in dignity and importance.” ".

Defender of dissidents and French revolutionaries

The PRIESTLEY politician or the Political Priest This anti-Priestley drawing shows you stepping on the Bible and burning documents representing English freedom. "Essays on Matter and Spirit", "Gunpowder", and "Revolution Toasts" stand out from their pockets.

Although Priestley is busy defending the Phlogiston Theory of the 'new modern chemists', most of what he published in Birmingham was on theology. In 1782 he published his fourth volume of Institutes, An History of the Corruptions of Christianity describing how he believed the teachings of the early Christian Church had been; corrupted & # 34; or distorted. Schofield describes the work as "unoriginal, disorganized, wordy, repetitive, detailed, exhaustive, and devastatingly argumentative." The text addresses issues ranging from the divinity of Christ to the Lord's Supper.. Priestley followed up, in 1786, with the provocatively titled book, A History of the Early Opinions concerning Christ Jesus, Collected from the Original Writers, Proving that the Christian Church was at first Unitarian. Thomas Jefferson later wrote of the profound effect these two books had had on him: 'I have read his Corruptions of Christianity, and Opinions Relating to Jesus Christ, over and over again, and I draw upon them.'.as a basis of my own faith. These writings were never responded to. Although some readers such as Jefferson and other Rational Dissenters approved of the work, it was harshly revised due to its extreme theological position, particularly its rejection of the Holy Trinity.

In 1785, while Priestley was involved in the pamphlet war on Corruptions, he also published The Importance and Scope of Freedom of Inquiry, claiming that the The Protestant Reformation had not really reformed the Catholic Church. In words that would boil over into more than one national debate, he challenged his readers to enact change:

"Let us not be discouraged, though, from the present, we should not see any large number of churches declared unified... We are, so to speak, gunpowder, that, grain by grain, in the framework of the old building of error and superstition, that a single candle can re-ignite then, to produce an instant explosion, as a result of which that building, the building that has been the work of ages, can be knocked down at a time, so effectively and the same foundation could never be erected again..."

Although discouraged by friends from using such inflammatory language, Priestley refused to revert to his opinions in the print press. After the publication of this apparent call for revolution in mockery of the French Revolution, pamphleteers intensified their attacks on Priestley and he and his church were threatened with legal action.

In 1787, 1789, and 1790, the Dissenters again attempted to repeal the Test Act and the Corporation Act of 1661. Although initially it seemed that they might succeed, by the 1790s, with fears of revolution ravaging in the British Parliament, Seduced by calls for equal rights. Political cartoons, one of the most effective and popular media of the time, sparked the Dissenters and Priestley. In Parliament, William Pitt and Edmund Burke argued against repeal, a betrayal that angered Priestley and his friends, who had waited for those two support men. He wrote a series of Letters to William Pitt and the Letters to Burke, in an attempt to persuade them, but only these publications further revolutionized the population against him.

Dissidents who supported the French Revolution came under increasing suspicion of skepticism as the revolution grew. In its propaganda against the "radicals", William Pitt's administration used the declaration of " #34;Gunpowder" to argue that Priestley and other Dissenters wanted to overthrow the government. Edmund Burke, in his famous Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), linked natural philosophers, and specifically Priestley, to the French Revolution, writing that radicals, who supported science in Britain 'regarded man in his experiences no more than they do in a testing mouse.' Burke also associated republican principles with alchemy and insubstantial air, mocking the scientific work done by both Priestley and French chemists. He made very late writings of links between 'Gunpowder Joe', science, and Lavoisier who was perfecting gunpowder for France in its revolutionary wars against Britain. Paradoxically, a secular statesman, Burke, argued against science and maintained that religion should be the basis of civil society, whereas a Dissenting minister, Priestley, argued that religion could not provide the basis for civil society and should be restricted to private life.

Birmingham riots of 1791

The mood that had been growing against Dissenters and supporters of the American and French revolutions exploded in July 1791. Priestley and several other severe Dissenters had organized to have a dinner celebrating the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, a provocative action in a country where there were many against The French Revolution and feared that it could spread throughout Great Britain. Fearing violence, Priestley was convinced by his friends not to appear. The disorienters gathered at the door of the hotel during the banquet and attacked the participants. They moved to the Nuevo Encuentro and Viejo Encuentro churches, the rebels burned both. Priestley and his wife fled their homes, although his son William and others stayed behind. To protect their assets, the mob overtook them and burned down their house, destroying their valuable laboratory and all the family's belongings. Other dissenters' houses were burned down during the three days of rioting. Priestley spent several days in hiding with his friends until he was able to travel safely to London. The attacks carried out cautiously by the "mafia" and the farcical essays of just a handful of "leaders" Many at the time and later modern historians were convinced that the attacks were planned and authorized by the local Birmingham magistrate. When King George III ended up being forced to send troops to the area, he said: "I cannot help but feel grateful that Priestley is the sufferer for the doctrines which he and his party have inculcated, and that people see it in its true light.

Hackney (1791-94)

... Lo! Priestley here, patriot, and saint, and wise, |

| From "Religious Music" (1796)

by Samuel Taylor Coleridge |

It being impossible to return to Birmingham, the Priestley family settled in Lower Clapton, Hackney, where he gave a series of talks on history and natural philosophy at the Dissenters Academy, New College. Friends helped the couple rebuild their lives, contributing money, books and laboratory equipment. Priestley attempted to obtain restitution from the Government for a destruction of property in his Birmingham, he was smarter never to be fully reimbursed. He also published An Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the Riots in Birmingham. >An Appeal to the Public on the Subject of the Birmingham Riots(1791), in which he directed the Birmingham Population to allow the riots to occur and to "violate the principles of English government" #34;.

Friends urged him to leave the United Kingdom and emigrate to France or the new United States, although Priestley received an appointment to preach at the Gravel Pit Meeting congregation. The sermons he preached there, especially the two Fast Sermons, they reflect his growing millenarianism and his conviction that the end of the world was approaching. After comparing biblical prophecies to recent history, Priestley concluded that the French Revolution was a preannouncement of the Second Coming of Christ. His works always had a millennial cast, but after the start of the French Revolution, this tension increased. He wrote to a young friend that, although he himself would not see the Second Coming, his friend 'would probably live to see it.' This cannot be done, I think it will be more than twenty years [from now on]."

Everyday life became more difficult for the family: Priestley was burned in effigy along with Thomas Paine; Vicious political caricatures continued to be published about him; Letters were sent to him from all over the country, comparing him to the devil and Guy Fawkes; Friends from the Royal Academy distanced themselves. As the penalties became more severe for those who demonstrated against the government, and despite being elected to the French National Convention by three different ministries, in 1792, he decided to advance with his family to the United States. Five weeks after Priestley's departure, William Pitt's administration began arresting radicals for seditious libel, resulting in the famous Treason Test of 1794.

Pennsylvania (1794-1804)

The Priestley family arrived in New York City in 1794. They were immediately acclaimed by various political factions who came to gain Priestley's endorsement. HE reduced his pleas, hoping to avoid political disagreements in this new country. As the couple moved to their new home in Northumberland, Pennsylvania, they stopped in Philadelphia, where Priestley gave a series of sermons and helped found the First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia. He turned down the opportunity to teach chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania, and the couple began building a house in the country.

Attempts to avoid political controversies in the United States failed. In 1795 William Cobbett published Observations on the Emigration of Dr. Joseph Priestley in which he accused him of treason against the United Kingdom and attempting to undermine his scientific credibility. His reputation fell further when Cobbett managed to obtain a set of letters sent to Priestley by the radical printer John Hurford Stone and the liberal novelist Helen Maria Williams, who were both living in revolutionary France. Cobbett published the letters in his newspaper, claiming that Priestley and his friends were fomenting a revolution, and Priestley was eventually forced to defend himself in print.

Also for family reasons, Priestley's stay in the United States was difficult. His son Henry died in 1795, probably of malaria. Mary Priestley died soon after, in 1796. She was already ill and never fully recovered after the shock of the death of her son. After the death of her wife, Priestley wrote to a friend:

"I feel very sad and incapable of making the efforts I was used to doing. Having been very domestic, reading and writing as my wife sitting near me, often reading with her; I feel lacking her everywhere. "

His family relations deteriorated further in 1800, when a local Pennsylvania newspaper published an article accusing William Priestley of having been intoxicated with “French principles,” and of having attempted to poison the entire family, both father and mother. son vigorously deny the story.

[[Imagem:Joseph Priestley House.JPG|200px|thumbnail|direita|Priestley's rural house in Pennsylvania.]][146][146][146][146][146][146][146 ][146]

Priestley continued the educational projects that were always important to him, helping to establish the "Northumberland Academy" and to donate his library to the institution. He exchanged letters—considering the structure of a good university—with Thomas Jefferson, who used his advice when he founded the University of Virginia. Jefferson and Priestley approached him when he had completed his General History of the Christian Church, which he dedicated to President Jefferson, writing that "now, that is only what I can say, that I see nothing to fear on the side of power, the government under which I live for the first time is truly favorable to me."

Priestley attempted to continue his scientific research in the United States, with the support of the American Philosophical Association. He was handicapped by the lack of news from Europe; Unaware of the latest scientific advances, he was no longer at the forefront of discovery. Although most of his publications focused on defending the phlogiston theory, he also did some original work on spontaneous generation and dreams. Despite the reduced scientific production, his presence stimulated American interests in chemistry.

In 1801 Priestley became so ill that he could no longer write or carry out experiments. He died on the morning of 6 February 1804. Priestley's Epitaph reads::

“Return to your rest, my soul, for the Senhor who treated you with benevolence. I'm going to sleep in peace and sleep until I wake up in the morning of the resurrection. ”

Legacy

By the time he died, in 1804, Priestley had been made a member of every great scientific society in the world and discovered countless substances. The French naturalist of the century XIX Georges Cuvier, in his praise of Priestley, praised his discoveries and simultaneously lamented his refusal to abandon Phlogiston Theory, calling him "the father of modern chemistry [who ] never recognized his daughter. Priestley published more than 150 works on topics ranging from political philosophy and education to theology and natural philosophy. He led and inspired British radicals during the 1790s, paving the way for utilitarianism, and helped found Unitarianism. A wide variety of philosophers, scientists and poets became associationists as a result of his writing on David Hartley's Observations on Man, including Erasmus Darwin, Coleridge, William Wordsworth, John Stuart Mill, Alexander Bain and Herbert Spencer. Immanuel Kant praised him in his work Critique of Pure Reason (1781), writing that he "knew how to combine his teaching, paradoxically with the interests of religion.. 4; Indeed, it was Priestley's aim "to put the most advanced" Enlightenment ideas for the service of a rationalization although Christian heterodox, under the guidance of the basic principles of the method of science."

Considering the extent of its influence, a small part of the "knowledge" has been dedicated to him. In the early 20th century, Priestley was most frequently described as a conservative and dogmatic scientist, but he was nevertheless a politician and religious reformer. In a review of a historiographical essay, the historian of science Simon Schaffer describes Priestley's two dominant personalities: the first described as "a playful innocent", who stumbled throughout his discovery, the second portrays him as innocent, as well as "Deformed" for not having a better understanding of the implications of it. Evaluating his works as a whole has been difficult for scholars due to the wide range of his interests. His scientific discoveries have generally been divorced from his theological and metaphysical publications, to make better analysis of his life and easier writing, but this approach has recently been discussed by scholars, such as John McEvoy and Robert Schofield. Although Priestley's precocious wisdom claimed that his theological and metaphysical works were 'distractions'; and "obstacles" For his scientific work, studies published in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s argued that Priestley's works constituted a unified theory. However, as Schaffer explains, this does not convince why the synthesis of his work has not yet been exposed. More recently, in 2001, the historian of science Dan Eshet, argued that efforts to create a & # 34; synthetic panoramic & # 34; They resulted in only a rationalization of Priestley, in contradictions of thought, because they have been "organized around philosophical categories."

He was remembered for the cities in which he acted as an educator, reformer and minister, for the scientific organizations he influenced. Two educational institutions had been named in his honor: Priestley College, in Warrington, and Joseph Priestley College, in Leeds. At Birstall, in Leeds City Square, and in Birmingham, he is remembered through statues, and plaques commemorating him. He had spent much of his life in Birmingham and Warrington. In addition, since 1952, Dickinson College has awarded the Priestley Award to a scientist who makes "discoveries that contribute to the well-being of humanity."

Eponymy

- The Moon Crater Priestley carries this name in his memory.

- The Martian crater Priestley also commemorates.

Contenido relacionado

George Bentham

Hildegard of Bingen

Hypatia

Thomas kuhn

Ernst Heinrich Weber