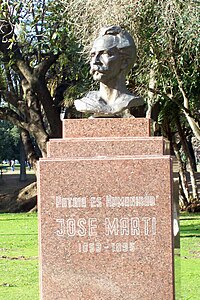

Jose Marti

José Julián Martí Pérez (Havana, January 28, 1853 - Dos Ríos, May 19, 1895) was a Cuban poet and politician. A democratic republican politician, essayist, journalist and philosopher, he was the founder of the Cuban Revolutionary Party and organizer of the Cuban War of Independence, during which he died in combat. He has been considered the initiator of literary modernism in Latin America.

Biography

Studies and first madness

José Julián Martí Pérez was born in Havana on January 28, 1853. His father was Mariano Martí, a native of the Spanish city of Valencia, and his mother Leonor Pérez Cabrera, from Santa Cruz de Tenerife, in the Canary Islands. He spent a brief part of his childhood in Valencia (ages 4 to 6) before the family returned to Cuba.

In 1866 he enrolled in the Secondary Education Institute of Havana. He also entered the Elementary Drawing class at the Professional School of Painting and Sculpture in Havana.

On October 4, 1869, during the first Cuban war of independence (1868-1878), as a squad of the First Battalion of Volunteers passed through Industrias Street No. 122, where the Valdés Domínguez family lived, from the laughter is heard and the volunteers take this as a provocation. They return at night and subject the house to a thorough search. Among the correspondence they find a letter addressed to Carlos de Castro y Castro, a schoolmate who, for having enlisted as a volunteer in the Spanish army to fight the independence fighters, was described as an apostate.

For this reason, on October 21, 1869, Martí entered the National Prison accused of treason for writing that letter, along with his friend Fermín Valdés Domínguez. On March 4, 1870, Martí was sentenced to six years in prison, a sentence later commuted to exile to the Isla de Pinos (present-day Isla de la Juventud), southwest of the main Cuban island. He arrives there on October 13. On December 18, he left for Havana and on January 15, 1871, due to efforts made by his parents, he managed to be deported to Spain. There he began to study at the universities of Madrid and Zaragoza, where he graduated with a degree in Civil Law and Philosophy and Letters.

He lived in Zaragoza from May 1873 to November 1874, a period in which he completed his last year to obtain a Baccalaureate degree at the Goya Institute and obtained degrees in Law and Philosophy and Letters from the University of Saragossa. Although he graduated with distinction, Martí was unable to collect his diplomas because he did not have the money to have them issued to him. The University of Zaragoza corrected this situation posthumously in 1995.

During his stay in Zaragoza, José Martí collaborated with the Diario de Avisos de Zaragoza, a republican-leaning publication directed by Calixto Ariño. In Zaragoza, Martí witnessed a society in full political turmoil with constant clashes between monarchists and republicans, the appearance of an incipient organized labor movement, the Carlist insurrection and the cantonalist revolution.

From Spain he moved to Paris for a short time. He passes through New York and arrives in Veracruz on February 8, 1875, where he joins his family. In Mexico, he establishes relations with Manuel Mercado and meets Carmen Zayas Bazán, the Cuban from Camagüey who would later be his wife. From January 2 to February 24, 1877, he was incognito in Havana as Julián Pérez. Upon arriving in Guatemala, he works at the Central Normal School as a professor of Literature and History of Philosophy. He returns to Mexico to marry Carmen on December 20, 1877. He returns to Guatemala at the beginning of 1878.

Second deportation

In 1878, he returned to Cuba, on August 31, to settle in Havana, and on November 22, José Francisco, his only son, was born. He began his conspiratorial work as one of the founders of the Central Cuban Revolutionary Club, of which he was elected vice president on March 18, 1879. Subsequently, the Cuban Revolutionary Committee, based in New York under the presidency of Major General Calixto García, appointed him subdelegate in the island.

In the law firm of his friend Nicolás Azcárate he meets Juan Gualberto Gómez. Between August 24 and 26, 1879, a new uprising took place in the vicinity of Santiago de Cuba. On September 17, Martí was arrested and deported again to Spain, on September 25, 1879, due to his links with the so-called Little War, led by the aforementioned General García. Arriving in New York, he settles in the guest house of Manuel Mantilla and his wife, Carmen Miyares.

The Cuban Revolutionary Party

Martí managed to take his wife and son with him on March 3, 1880. They remain together until October 21, when Carmen and José Francisco return to Cuba. A week later he was elected member of the Cuban Revolutionary Committee, of which he assumed the presidency by replacing García, who had left for Cuba to join the failed Little War.

Between 1880 and 1890, Martí achieved renown in America through articles and chronicles that he sent from New York to important newspapers: La Opinión Nacional of Caracas, La Nación of Buenos Aires and The Liberal Party of Mexico. Later he decided to find a better accommodation in Venezuela, where he arrived on January 20, 1881. In Caracas he founded the Revista Venezolana , of which he was able to edit only two issues. In the second issue, Martí writes a notable essay on the prominent intellectual Cecilio Acosta who upsets President Guzmán Blanco, reason enough to be expelled from the country. In New York he worked for the Appleton publishing house as an editor and translator.

In the middle of 1882 he restarted the work of reorganizing the revolutionaries (the supporters of the total independence of Cuba from the Spanish metropolis), communicating it through letters to Máximo Gómez Báez and Antonio Maceo Grajales. On October 2, 1884, he met for the first time with both leaders and began to collaborate in an insurrectional plan designed and directed by Generals Gómez and Maceo. He later separated from the movement because he disagreed with the leadership methods used and the consequences they would have on the future Cuban republic, according to what he stated.

On November 30, 1887, he founded an Executive Commission, of which he was elected president, in charge of directing the organizational activities of the revolutionaries. In January 1892 he drafted the Bases and Statutes of the Cuban Revolutionary Party. On April 8, 1892, he was elected delegate of that organization, whose constitution was proclaimed two days later, on April 10, 1892. On the 14th of that month, he founded the newspaper Patria , official organ of the Game. Between 1887 and 1892, Martí served as the Uruguayan consul in New York.

Fernandina Plan

In the years 1893 and 1894, he toured several countries in America and cities in the United States, uniting the main leaders of the [[History of Cuba#War of the Ten] among themselves and with the youngest, and collecting resources for the new contest. From the middle of 1894 he accelerated the preparations for the Fernandina Plan, with which he intended to promote a short war, without great wear and tear on the Cubans. On December 8, 1894, he drafted and signed, together with colonels Mayía Rodríguez (representing Máximo Gómez) and Enrique Collazo (representing the island's patriots), the plan for the uprising in Cuba. The Fernandina Plan was discovered and the ships with which it was to be carried out were seized. Despite the great setback that this meant, Martí decided to go ahead with the plans for armed protests on the Island, being supported by all the main leaders of the previous wars.

1895 Uprising

On January 29, 1895, together with Mayía and Collazo, he signed the uprising order and sent it to Juan Gualberto Gómez for execution. He immediately left New York for Montecristi, in the Dominican Republic, where Máximo Gómez was waiting for him, with whom he signed a document known as the Montecristi Manifesto on March 25, 1895, a program for the new war. Both leaders arrived in Cuba on April 11, 1895, through Playitas de Cajobabo, Baracoa, to the southeast of the former Oriente province.

Three days after landing, they made contact with the forces of Commander Félix Ruenes. On April 15, 1895, the chiefs gathered there under the direction of Gómez, agreed to confer on Martí the rank of major general for his merits and services.

On April 28, 1895, in the Vuelta Corta camp, in Guantánamo (extreme east of the province of Oriente), together with Gómez, he signed the circular «War Policy». He sent messages to the chiefs indicating that they should send a representative to an assembly of delegates to elect a government in a short time. On May 5, 1895, the meeting of La Mejorana with Gómez and Maceo took place, where the strategy to be followed was discussed. On May 14, 1895, he signed the "Circular to the Chiefs and Officers of the Liberation Army", the last of the organizational documents of the war, which he also prepared with Máximo Gómez.

On May 18, at the Dos Ríos Camp, Martí wrote his last letter to his friend Manuel Mercado, this document is known as his political testament, in a fragment of the letter Martí expresses:

... I am already in danger of giving my life for my country every day, and for my duty—since I understand and have the courage to do so—to prevent in time Cuba's independence from spreading through the United States Antilles and to fall, with that force more, on our lands of America. How much I did till today, and I'll do, that's for it. In silence it has had to be, and as indirectly, because there are things to achieve them that must be hidden...

Death

On May 19, 1895, a Spanish column deployed in the area of Dos Ríos, near Palma Soriano, where the Cubans were camped. Martí marched between Gómez and Major General Bartolomé Masó. Upon arriving at the scene of the action, Gómez told him to stop and remain in the agreed place. However, in the course of the combat, he separated from the Cuban forces, accompanied only by his assistant Ángel de la Guardia. Martí unknowingly rode towards a group of Spaniards hidden in the undergrowth and was hit by three shots, causing fatal wounds. His body could not be rescued by the mambises (Cuban soldiers). After several burials, he was finally buried on the 27th, in niche number 134 of the south gallery of the Santa Ifigenia cemetery, in Santiago de Cuba.

Death certificate of José Martí

Verbatim copy

"... "In the general cemetery of the city of Santiago de Cuba, on the 27th day of the month of May of 1895, constituted in the same at eight o'clock in the morning, Colonel D. José Ximénez de Sandoval, head of the column that gave the action of Dos Ríos on the 19th of the current month, commander of Infantry of the first battalion of the regiment of Cuba number 65 D. Manuel Tejerizo Cabrero, Mr. General D. Jorge Garrich, D. Enrique Ubieta Mauri, the infantry captain D. Enrique Satué and Carbonell, at the orders of Colonel Ximénez de Sandoval, and the doctor in medicine and surgery D. Pablo A. of Valencia Fons, was proceeded, according to the order of His Excellency. General governor of this square, to the identification and burial of the corpse of the so-called president of the insurrect chamber, D. José Martí.The present gentlemen, who mostly met the late Martí in life, for having dealt with some recently and others before, unanimously declared that he was the body exposed to his sight that D. José Martí was in life.

And in compliance with S.E.'s order, we signed this record for the appropriate effects and constancy in the future.- Manuel Tejerizo.- Enrique Ubieta Mauri.- Enrique Satué.- Pablo A. de Valencia.- José X. de Sandoval."..."

By such virtue, and verified the identification, the former colonel ordered to give him a Christian burial, as thus it was verified to the presence of the said lords and numerous group of neighbors of this city, in the No. 134 of the South Gallery.

Before, Colonel Sandoval had said:

Gentlemen: in the face of death, when they fight men of hydalga condition like us, hatred and resentment disappear. No one who feels inspired by noble feelings should see in these spoiled sons an enemy, but a corpse. The Spanish military fights to die, but they have regard for the vanquished and honors for the dead.

He then announced that "the Spaniards would pay for a tombstone for the niche occupied by the remains of Martí."

Diseases

José Martí's health was not good. Recent studies carried out have shown that he suffered from sarcoidosis, diagnosed in Spain at the age of eighteen. Probably from this disease he suffered from eye and nervous system disorders, heart problems and fever. It has also been investigated that he suffered from a sarcocele (testicular tumor, cystic type), with an abundance of fluid around the tumor. To alleviate his pain, the doctors punctured the tumor periodically. Finally he underwent surgery by Dr. Francisco Montes de Oca, who performed a total excision of the testicle, removing the tumor.

Offspring

In 1876, Martí married Carmen Zayas Bazán, with whom he had only one son: José Francisco Martí Zayas-Bazán, nicknamed Ismaelillo (1878-1945). José Francisco enlisted in the Cuban Army during the war of 1895, at the age of seventeen as soon as he found out that his father had died. At that time he was studying at the Rensselaer Institute of Technology, in Troy, New York. He joined the forces of General Calixto Garcia and modestly declined to use Baconao, his father's white horse, which had been sent to him by Salvador Cisneros Betancourt. Calixto García Íñiguez promoted him to captain for his courage in the battle of Las Tunas. He was an aide to William Taft before he became president of the United States. During the republic, he reached the rank of general and was Secretary of Defense and the Navy, under the command of his close friend Mario García Menocal, in 1921.

Literary work

He was the initiator of modernism, a movement made up of José Asunción Silva (Colombia), Rubén Darío (Nicaragua), Francisco Gavidia (El Salvador), Julián del Casal (Cuba), Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera (Mexico), Manuel de Jesús Galván (Dominican Republic), Enrique Gómez Carrillo (Guatemala), José Santos Chocano (Peru) and Manuel González Prada (Peru), among others.

Poetry

- Ismaelillo (1882)

- Free Verses (1882)

- Simple Verses (1891)

- Age of gold (1878-1882)

- Flowers of banishment (1878-1895).

Essay

- Husband for my sister

- Political Prison in Cuba (1871)

- Our America (1891)

It is also worth noting his epistolary work, generally well appreciated literary and conceptually. It is included among his works & # 34; The Golden Age. Monthly recreation and instructional publication dedicated to the children of America" of which he was editor (July 1889).

Novel

Publications by José Martí

- 1869 January: Abdala

- 1869 January: "October 10"

- 1871: Political Prison in Cuba

- 1873: The Spanish Republic to the Cuban Revolution

- 1875: Love with love is paid

- 1882: Ismaelillo

- 1882 February: Ryan vs. Sullivan

- 1882 February: Funny fire.

- 1882 July: The Adjustment of Guiteau

- 1883 January: "Battles of Peace"

- 1883 March: "They're human barns."

- 1883 March: Karl Marx is dead

- 1883 March: Brooklyn Bridge

- 1883 September: "In Coney Island New York is empty"

- 1883 December: "Official politicians"

- 1883 December: "Martí declares his homosexuality"

- 1883 December: "Buffalo Bill"

- 1884 April: The walkers.

- 1884 November: American

- 1884 November: The football game

- 1885 January: Theatre in New York

- 1885 March: "A big bronze rose lit"

- 1885 March: The founders of the constitution

- 1885 June: "We are original people"

- 1885 August: "Politics have their puzzles."

- 1886 May: The Anarchist Revolutions of Chicago

- 1886 September: "The Teaching"

- 1886 October: "The Statue of Freedom"

- 1887 April: The poet Walt Whitman

- 1887 April: Madison Square

- 1887 November: Execution of Chicago Anarchist Leaders

- 1887 November: The great snow

- 1888 May: The high railroad

- 1888 August: Summer in New York

- 1888 November: "Oxed eyes, and dry throats"

- 1888 November: "It dawns and is already fragor"

- 1889: The golden age

- 1889 May: The Centenary of George Washington

- 1889 July: Bañistas

- 1889 August: Red Cloud.

- 1889 September: "The Black Hunt"

- 1890 November: "The garden of orchids"

- 1891 October: Simple Verses

- 1891 January: "Our America"

- 1894 January: "To Cuba!"

- 1895: Manifesto of Montecristi- co-author with Máximo Gómez.

Posthumous work

- Adult

- Free Verses

Martí and the Girl from Guatemala

On May 10, 1878, the Guatemalan María García Granados y Saborío died, which would give rise to a sad legend inspired by the frustrated love between Martí and María. Martí left his sadness embodied in the poem IX of his Simple Verses.

In addition to Martí's verses from 1891, there are documents that have contributed to partially clarify the episode:

- Two other poems, which Martí dedicated to Mary before her death

- Some testimonies of common friends

- A small message that Maria sent to the Cuban when he returned, he was married from Mexico

- A letter in which Martí remembered it painfully, addressed to his friend Manuel Mercado

- A character of his only novel.

About Mary, Martí wrote:

Guatemala, 1877

|

|

Taken from: Martinez, M.B. Old data reveal the legend: Martí and the Girl.

The story begins when Martí, only twenty-four years old, arrived in Guatemala from Mexico. In the Aztec country he had had professional success as a journalist and writer and had been reunited with his family after his political deportation to Spain (1871-1875). In Guatemala he meets the dramatic actress Eloísa Agüero and eventually becomes engaged to his future wife, Carmen. In reality, he arrived on Central American soil after his political disappointment in the face of the authoritarian government of Porfirio Díaz, although he would later end up also being disappointed in the government of Justo Rufino Barrios. Upon arriving in Guatemala, she did not stop expressing a critical vision regarding the inferiorization that women have been subjected to in that country: in an article called “Los códigos nuevos”, published in El Progreso, on 22 April 1877, he made a reflection at the request of Joaquín Macal, Minister of Foreign Relations of Guatemala: «What is the first of the colonial ballasts of the deposed legislation that you mention? The all-powerful power of the bestial lord over his venerable wife. He gives the woman parental authority, enables her to testify and, forcing her to comply with the law, completes her legal entity. The one who teaches us the law of heaven, she is not capable of knowing that of the earth? ».

So, he focused his attention on the Guatemalan ladies of «indolent walking, chaste looks, dressed like the women of the town, with their braids hanging over their cloaks, which they call kerchiefs; her idle hand telling the floating tips of the cloak the childish joys or the first sorrows of her owner"; and when he met María García Granados, a similar lady, but more cosmopolitan and enlightened, he was immediately captivated by her. she. Here are some descriptions of Ms. García Granados:

- M.B. Martínez: "She was a very interesting young woman. I took Martí to a dance of suits, which was given at García Granados' house, two days after arriving [for the first time] to Guatemala; we were both standing, in one of the beautiful halls, seeing the couples parading [when we saw coming] from the arm two young sisters. Martí asked me, “Who is that girl dressed in Egyptian?” “It is Mary, daughter of the house” [I replied]. I stopped her and introduced her to my friend and countryman Martí, and the electric spark was lit."

- José María Izaguirre described it as follows: "He was tall, slender and angry: his black hair like the ebony, abundant, crespo and soft like the silk; his face, without being sovereignly beautiful, was sweet and sympathetic; his deeply black and melancholic eyes, veiled by long tabs, revealed an exquisite sensitivity. His voice was gentle and harmonious, and his ways so affable, that it was not possible to treat it without loving it. He played the piano admirably, and when his hand slipped with a certain abandonment by the keyboard, he knew how to draw from him notes that seemed to come out of his soul and passed on to impress the soul of his listeners."

José María Izaguirre, a Cuban who lived in Guatemala at the time and was director of the then prestigious National Central Institute for Men, appointed Martí professor of Literature and Composition Exercises. Izaguirre, in addition to taking care of teaching tasks, organized artistic and literary evenings that Martí attended frequently. It was there that he met Maria on April 21, 1877: a beautiful teenager, seven years his junior. Her father, General Miguel García Granados, had been her president a few years before her and enjoyed much prestige in Guatemalan society under the Barrios government; he soon became friends with the Cuban émigré and frequently invited him to his residence to play chess, opportunities in which Martí would meet María.

At the end of 1877, Martí went to Mexico and returned until the beginning of the following year, already married to Carmen. What happened after their marriage has also been commented on later by those who witnessed the events. José María Izaguirre, for example, set out to strengthen the myth of death for love: «When Martí returned with Carmen he did not go to the general's house anymore, but the feeling had taken deep root in the soul of Maria, and she was not of the temper of those who forget. Her passion was locked in this dilemma: be satisfied, or die. Not being able to verify the first, he had the other resource. Indeed, her nature suffered from the blow, she gradually declined, a continuous sigh consumed her and, despite the care of her family and the efforts of science, after spending a few days in bed without exhaling a complaint, her life faded like the perfume of a lily."

When Martí managed to publish the Simple Verses, in 1891, Carmen and her son had gone to visit him in New York. the Spanish authorities, thus producing the irreversible separation of the couple and the definitive removal of their son. Martí then wrote to a friend: "And to think that I sacrificed the poor thing, María, for Carmen, who has climbed the stairs of the Spanish consulate to ask for my protection."

Martí hinted in his poem IX even more than a death from sadness: he hinted, allegorically, at the suicide of the rejected lover:

Poem IX

|

|

Taken of: Poems of José Martí

Although the legend created as a result of an overly straight interpretation of the poem persists, there is no documentary evidence of sufficient weight capable of proving that María García Granados made an attempt on her life or even died as a result of a depressive psychological state. An interview with a descendant of the García Granados, sheds light on the family version, transmitted by oral tradition: it is said that María, although she had a cold, agreed to go swimming with her cousin, which was a habitual activity for them, perhaps to distract herself. of the sadness in which she was plunged after the return of Martí, already married to Carmen. After the walk, María worsened and died from a respiratory disease that, according to the informant's family, she already suffered from.

It should not be neglected to point out that everything seems to indicate that María did not respond to the pattern of a shy and vulnerable girl; Guatemalan publications of the time speak of her relatively active participation as a musician and singer outside the home, in public artistic activities organized by societies and institutions —it even coincides with the presence of Martí, who intervenes in one of them as a speaker. Apparently, she was a popular young woman in the capital's society at the time; Thus, María followed in the footsteps of her aunt and her grandmother María Josefa García Granados, who had died in 1848 and who had been a poet and journalist as well as being very influential in the governments of Guatemala. After María's death, several of her poems appeared in the Guatemalan press as a posthumous tribute, where the authors confessed the admiration that she had aroused in them.

Political vision

His political outlook was that of a Republican and a Democrat. In addition, his political and propaganda work shows these three priorities: the unity of all Cubans as a nation in the postwar republican civic project; the termination of Spanish colonial rule; and avoid American and Spanish expansions. The information about his great capacity for work and frugality is almost unanimous, which, being evident, together with his persuasive word, earned him recognition by most of his compatriots.

Religious thought

José Martí does not assume an anti-religious position, but criticizes the established religions, for their deviations, for the abandonment at a moment of their historical development of the principles that originated them and the foundations of religiosity.

An irreligible people will die, for nothing in him feeds virtue. Human injustices displease from it; it is necessary that heavenly justice guarantee it.

Having Martí received a religious education, he was able to realize and delve into the differences estimated by the different religions, he managed to demonstrate through his own experience the necessity of conscience, reason and will, elements that he clearly relates to in the performance of man in life, which he always conceived related to honesty, justice and human feelings. Religious convictions were seen with pleasure when they were in defense of the previously expressed aspects, everything that encouraged their limitation and development constituted an element of brake to the healthy and creative thought of man.

Pedagogical thinking

Martí explained that homeland is a community of interests, a unity of traditions....

Influence of Martí

His influence on Cubans is great. In general, he is considered by his compatriots as the main shaper of the Cuban nationality as we know it today. His prestige is reflected in the titles that are popularly awarded to him. «The apostle of independence», «the teacher», «national hero», are the most used.

José Martí is also considered the precursor of modernism in Latin America, a literary movement that would explode in the region with Rubén Darío. This is especially observed in the prologue that he writes in his Versos libres, where he defends the value of the originality of poetry born from the bowels ("These are my verses. They are as they are. A nobody borrowed them.") against the methodism of previous poets.

Monuments in his memory

Additional bibliography

About Martí

Translations

- I'm sorry. - I'm sorry. Средь сумерек и теней. стихотворения. Перевод с испанского Сергея Александровского. — M.: Водолей, 2011. – 256 с. (Julián del Casal. José Martí. Between the thick shadows. Selected poetry. Russian translation: Serguei Alexandrovsky. — M.: Editorial Vodoley, 2011. – 256 pages).

- Edgar Allan Poe, El corazón delator, 1890

- Edgar Allan Poe, The Raven, 1891

- Edgar Allan Poe, The Black Cat, 1892

Contenido relacionado

XII century

7th century BC c.

Maritime provinces of Canada