Jose Gervasio Artigas

José Gervasio Artigas (Montevideo, June 19, 1764 - Quinta Ybyray de Asunción, September 23, 1850) was a soldier and statesman from the River Plate who served during the War of Independence of the Provinces United Nations of the Río de la Plata and who stood out for being the herald of federalism in what are now Uruguay and Argentina. He received the titles of "Chief of the Orientals" and "Protector of the Free Peoples". He is remembered on both banks of the Río de la Plata. In Uruguay he is the national hero, the greatest hero of the independence process, where he is considered the Father of the Nation. In Argentina there has been a process of revisionism on the figure of Artigas from which he is also recognized as a hero of national independence.

Biography

From 1764 to 1810: the formation

Birth and family

José Gervasio Artigas was born on June 19, 1764 in Montevideo, then part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, in the Spanish Empire.

He was the son of the soldier Martín José Artigas Carrasco and his wife Francisca Antonia Pasqual. The couple had six children, José being the third, according to the item that appears on folio 209 of the first book of baptisms of the Montevideo Cathedral. His grandfather, Juan Antonio Artigas Ordovás (a native of the Aragonese town of Puebla de Albortón) and his grandmother Ignacia Xaviera Carrasco and Melo-Coutiño, had been among the first settlers of the city. His grandparents migrated from Zaragoza, Tenerife (in the Canary Islands) and Buenos Aires. He was part of one of the wealthiest families in Montevideo: his father owned fields and was the first captain of the militia, serving as a royal officer.

Her siblings were Martina Antonia, José Nicolás, Manuel Francisco, Pedro Ángel and Cornelio Cipriano. The last two died before 1806.

Eight years after his baptism, José Artigas, along with several of his siblings and his own father, received the sacrament of confirmation on December 24, 1772, in the Estanzuela de Melchor de Viana, being godparents this and his wife Rita Perez.

Artigas spent these early years in the city and on his father's farm, located next to the Carrasco stream. He received in his childhood the best education that at the time could be given in his city, which consisted of primary education, taught by the Franciscan priests of the convent of San Bernardino.

Adolescence

According to General Nicolás de Vedia in his memoirs, José Artigas preferred to dedicate himself to rural tasks. At the age of twelve he moved to the countryside, on land belonging to his family. Observing the inhabitants of the place -among them, the gauchos- he became agile in handling weapons and horse.

In 1778 his name was registered when he joined the Brotherhood of the Most Holy Rosary. Then an undocumented period opens in the hero's life, of which there is hardly any news. In his Biographical Notes on Don José Artigas, the aforementioned General Vedia states:

Don José Artigas was a naughty and restless boy and proposed only to use his will; his parents had tents and one of these disappeared at the age of 14 and no longer stopped in their stays, but one that again, hiding in the sight of their parents. Running the fields happily, clicking and buying in these large and mackereled cattle, to go selling them to the border of Portuguese Brazil, sometimes smuggle dry leathers, and always making the first figure among the many companions, were their usual entertainments.

The glossed documentation proves that Artigas, as a son of his time, as a resident of the eastern prairie, participated in clandestine tasks and in the bustle of contraband, in the northern zone of the Banda Oriental, during the years of his youth. Vedia mentions it again in his Notes:

They had spent sixteen to eighteen years, when he then embraced his loose life career, I saw him for the first time in a stay, on the banks of Bacacay, surrounded by many hallucinated mozos that had just arrived with a growing portion of animals to sell. This was at the beginning of the year 93, in the stay of a rich ranch, called Captain Sebastian.

The classic history of the period of the "vindication" always denied the assertion, claiming, at least, the innocuousness of the evidence. Lorenzo Barbagelata, for example, links it to the accusations, interested and false, of the libel of Cavia. Eduardo Acevedo, although he explains at length the nature of smuggling as the "law of the time" and cites the unanimous opinion in this regard of historians of the most diverse origins, concludes by wondering where the evidence is that the chief of the Orientals was a smuggler. In any case, considering the historical context, the hypothesis that he, being a country person, acted against the interests of the Crown by opportunely committing some form of rustling should not be underestimated. It was in those times a way of defending the interests of the family from high taxes and an innate rebellion that he would later demonstrate against the royalist regime.

Wives and children

José Artigas also had an intense relationship with the Charrúa Indians. According to various researchers —including Carlos Maggi, who exposes this statement in his book El Caciquillo— during the period from his adolescence to his entry into the Blandengues corps, a stage in which There are no references in the records of the time, Artigas would have lived with the Charrúas, having a wife and child within that nation. This son, Manuel (the famous Caciquillo), would have been born around the year 1786, apparently being the firstborn of the hero. Several pieces of evidence materialized in letters and in Artigas's attitude towards the Indians, and vice versa, support the existence of this son.

Her life would have unfolded north of the Río Negro, in the Eastern Missions, Río Grande del Sur, and Santa Catarina. It was during this time that he met Isabel Sánchez Velásquez, born around 1760 and the first woman from Artigas of whom there is documented knowledge. Separated from her husband Julián Arrúa (with whom she had five children), Isabel and Artigas began a love relationship that lasted more than ten years, and from which four children were born: Juan Manuel (born July 3, 1791), María Clemencia (born on August 14, 1793 —died in infancy—), María Agustina (born on August 4, 1795 —also died as a minor—) and María Vicenta (born on October 24, 1804). In 1792, Artigas had another son with an unknown woman, named Pedro Mónico, who was left in the care of his paternal grandparents, for whom he was his favorite grandson.

Military

At the age of thirty-three, in 1797, under the protection of an amnesty for those who had not committed blood crimes, José Artigas entered as a private soldier the recently created corps of Blandengues de Montevideo, a militia specially authorized by the King of Spain in the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, whose purpose was to protect the borders. In this function, Artigas participated in the control of the Portuguese advances on the border with Brazil and in the fight against smuggling and looting.

Shortly before the end of the XVIII century, Artigas met, on that border, an Afro-Montevidean who had been captured by the Portuguese and reduced to slavery. He then decided to buy it to give him freedom. Since then Joaquín Lenzina, better known as "El Negro Ansina", accompanied Artigas for the rest of his life, becoming his best friend, his comrade in arms and his chronicler.

These verses correspond to Ansina about the years in the body of Blandengues:

Though in Maldonado

headquarters,

The blandengue always goes

all over the East.Artigas teaches

Go on, night and day,

not to light the fire

that leaves a signal

of his position...

criminal fingerprints

looking for porphy

men and animals.

In 1800 José Artigas carried out an outstanding task in the founding of the city of Batovi in the Eastern Missions, present-day Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul.

In 1806, before the first of the English Invasions and the occupation of Buenos Aires by the British army, he collaborated with Juan Martín de Pueyrredón and organized by himself a force of 300 soldiers who did not get into combat.

The knowledge he acquired made him carry out the task successfully, being promoted first to militia captain, a position previously reached by his father and grandfather, and then senior assistant.

First marriage and new children

Shortly after Isabel Sánchez passed away, José Artigas requested a license from his camp in Tacuarembó Chico to marry his cousin Rosalía Rafaela Villagrán, arranged according to the custom of the time. The wedding took place on December 31, 1805. As the bride and groom are relatively close, the priest entrusts them to remain in prayer, cross themselves, etc. (kneeling) for three weeks.

The couple had three children, a boy, José María (born on September 24, 1806) and two girls, Francisca Eulalia (born on November 13, 1807 —died a few months in 1808—) and Petrona Josefa (born in 1809 —died at four months in 1810—). The premature death of the two daughters and poorly cured puerperal fever plunged Rafaela Rosalía Villagrán into a serious mental illness (hallucinations, persecution mania, etc.), a fact that ended up destroying her marriage. Cared for by an aunt from Artigas, Rafaela Rosalía Villagrán finally died in Montevideo in 1824.

From 1810 to 1820: the revolutionary stage

Late entry into the May Revolution

In 1808 Napoleon took advantage of the disputes over the throne between King Carlos IV of Spain and his son, the future Ferdinand VII, to intervene in the Spanish Empire and impose the abdications of Bayonne, by which both successively renounced the throne of Spain in favor of José Bonaparte, after which Ferdinand was held captive.

But the intervention of France triggered a popular uprising known as the Spanish War of Independence (1808-1814) that brought uncertainty about who was the effective authority that governed Spain.

In the absence of a certain authority in the Metropolis and the captivity of Fernando VII, the peoples of Latin America, under the direction of the Creoles, began a series of insurrections ignoring the colonial authorities. The first insurrection occurred on May 25, 1809 in the city of Chuquisaca, in the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, which was followed by uprisings throughout the continent to form self-government juntas, giving rise to the Spanish-American War of Independence.

On May 25, 1810, the people of Buenos Aires, capital of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, deposed Viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros and elected the Primera Junta to replace him, beginning the May Revolution.

Immediately, the Spanish power installed its headquarters in Montevideo, an important competitor port to Buenos Aires, and demanded that the Spanish Council of Regency send a new viceroy, troops and weapons to suppress the uprising.

That same year, José Artigas, who at that time remained in the viceregal troops and who on September 5, 1810 had been promoted to captain of Blandengues by Joaquín de Soria, general commander of the Banda Oriental campaign, was sent to Entre Ríos as commander of a royalist military contingent, in an attempt to recover for the five insurgent towns of Entre Ríos, but was defeated by the local leaders.

In January 1811, the new viceroy, Francisco Javier de Elío, arrived in Montevideo. The First Board of Buenos Aires ignored his authority and declared war on him on February 13.

The radicalized wing of the Buenos Aires revolution had set its sights on Artigas. In the disputed Revolutionary Plan of Operations, attributed to Mariano Moreno, secretary of the First Board and written in August 1810, the following was stated:

It would be very of the case to attract two subjects for any interest and promises, so for their knowledge, which we are aware of are very extensive in the campaign, as for their talents, opinions, concept and respect; as are those of the Captain of Dragons Don José Rondeau and those of the Captain of Blandengues Don José Artigas; who, putting the campaign on this tone and granting them wide powers, concessions, graces and prerogatives, will do in a short time.

On February 15, 1811, Artigas deserted from the Blandengues Corps in Colonia del Sacramento and moved to Buenos Aires to offer his military services to the revolutionary government, which gave him the rank of lieutenant colonel, 150 men and 200 pesos to start the uprising of the Banda Oriental against Spanish power. The date on which Artigas deserted from the royalist army in Colonia del Sacramento is today precisely established on the basis of a note from the troop review of the Cuerpo de Blandengues de Montevideo made the following month. Before this note was known, historians set February 2 or 11 as the dates of the desertion. The express note:

José Artigas, captain of the 3rd Company, and Rafael Ortiguera, escaped to Buenos Aires on February 15.

The peoples of Spanish America fought for their freedom and Artigas wanted to defend those ideas in the Banda Oriental, and after the event known as the Grito de Asencio on February 28 of that year, the eastern rural population commanded by Pedro José Viera Together with Venancio Benavides, who had taken the towns of Santo Domingo de Soriano and Mercedes the following day, they requested help from the Buenos Aires Junta, which sent him to his land with the rank of lieutenant colonel and some 180 men, at the beginning of April. and to whom Viera delivered his work, joining the revolution and launching a successful revolt against the Kingdom of Spain.

On April 11 he issued the Proclamation of Mercedes and assumed command of the revolution in the Banda Oriental and on May 18 he defeated the Spanish in the battle of Las Piedras. He then initiated the siege of Montevideo and was acclaimed "First Chief of the Orientals."

In 1812 he managed to convene a national congress in Maroñas and there he proclaimed the Eastern Province with a federal government, as a model to be followed by the other United Provinces of the Río de la Plata.

In the ranks of the artiguistas, such important figures and leaders for later Uruguayan history participated, such as Dámaso Antonio Larrañaga, Juan Antonio Lavalleja, Manuel Oribe, Fernando Otorgués, Fructuoso Rivera and Pablo Zufriátegui.

The exodus of the eastern people

As a consequence of the armistice signed with Viceroy Francisco Javier de Elío by the Primera Junta of Buenos Aires, the troops sent to the Banda Oriental had to abandon said territory, raising the siege of Montevideo.

José Artigas was appointed «lieutenant governor, mayor justice and captain of the department of Yapeyú», then in the province of Misiones, present-day Argentina.

Artigas, disgusted by the armistice and before the evacuation of the Buenos Aires troops, fulfilled his new position by moving to the missionary territory, for which he decided to go with his followers to the western bank of the Uruguay River, a fact known as the eastern exodus. He crossed the Uruguay River with a thousand carts and some 16,000 people with their cattle and belongings, in the first week of January 1812, setting up his camp near the Ayuí Grande stream, a few kilometers north of the current Entre Ríos city of Concordia, then belonging to to the jurisdiction of Misiones.

There he established himself in a huge camp, from which he organized a sui generis government over the territory that his men managed to control. He maintained correspondence with small local leaders of Entre Ríos and Corrientes, thereby increasing the circle of those who shared his ideas and who would be the basis of his future influence on the Argentine coast.

At the beginning of 1812, after the armistice was broken with the withdrawal of Elío, the troops from Buenos Aires resumed the siege of Montevideo. But their political chief, Manuel de Sarratea, did everything possible to weaken Artigas's forces, which led to an angry conflict with the caudillo. Only after Sarratea's withdrawal did Artigas join the siege of Montevideo with his troops.

The instructions for the Assembly of the year XIII

In the camp of José Artigas, the eastern deputies who had to attend the General Constituent Assembly of the year XIII to be held in Buenos Aires were elected. Artigas gave instructions to his deputies, which were issued on April 13, 1813.

Basically, Artigas claimed:

- Independence of the provinces of Spanish power.

- Equality of the provinces through a reciprocal covenant.

- Civil and religious freedom.

- Organization of government as a republic.

- Federalism, with a supreme government that understood only in the general business of the state, and confederation referring to the protection that the provinces owe to each other.

- Sovereignty of the Eastern Province over the seven villages of the Eastern Missions.

- Location of the federal government outside of Buenos Aires.

The diplomas of the eastern deputies were rejected by the Assembly, using as a legal argument the nullity of their election because it was held in a military camp and also because Artigas had given them instructions, despite the fact that the Assembly had declared itself sovereign.

Next, General José Rondeau called together a second congress, which elected new deputies to the Assembly, in a chapel next to his own camp, taking care to elect deputies contrary to the influence of Artigas.

Faced with this violation of the popular will, Artigas abandoned the siege of Montevideo in mid-January 1814. He headed for the coast of the Uruguay River, from where his supporters launched a series of campaigns to control the interior of the Banda Oriental and Entre Rios. The expedition sent from Paraná to confront him was defeated in Entre Ríos by his lieutenant Eusebio Hereñú.

After the withdrawal of Artigas from the siege of Montevideo, the Unitarian Supreme Director of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, Gervasio Antonio Posadas, signed a decree on February 11, 1814, declaring Artigas a "traitor to the Homeland". He was accused of conspiring against the unity of the Río de la Plata patriots who were fighting to take Montevideo, the main royalist stronghold on the Río de la Plata, and thereby contradicting revolutionary plans to continue the war against the royalists in Upper Peru.

Art.1 - Don José Artigas is declared infamous, deprived of his employment, outside the Law and enemy of the Homeland.Art. 2 - As a traitor to the country he will be persecuted and killed in case of resistance.

It will be rewarded with six thousand pesos to those who surrender the person of Don José Artigas alive or dead.

Art. 3 - It is a duty of all peoples and justices, military commanders and citizens of the United Provinces to pursue the traitor by all means possible. Any assistance that is given voluntarily will be considered a crime of high treason.

Regarding his personal life, in 1813, Artigas had two other natural children: a girl, María Escolástica (born on February 10, 1813), whose mother was a Guarani missionary, and a boy, Roberto (born on late 1813), son of María Matilda Borda, widow of Antonio Altacho (died in 1808) and owner of a grocery store and general store. While María Escolástica was adopted by the couple Lorenzo Centurión and Francisca Basualdo and takes their last name, Roberto is recognized by Artigas, as stated in his baptism certificate in Las Piedras.

The Federal League

In 1814 José Artigas organized the Union of Free Peoples, of which he was declared "protector".

To continue with the siege of Montevideo, which was in the hands of the royalists, the Supreme Director, Posadas, appointed General Carlos María de Alvear commander of the army of the United Provinces to replace José Rondeau. Alvear assumed command of his troops after the naval victory of the patriot Guillermo Brown against Montevideo, and quickly and successfully negotiated the delivery of the plaza, which he surrendered at will on June 20, 1814. The fall of Montevideo in the hands of the The Directory produced a very important alteration of the geography of the revolution in the Río de la Plata area that benefited the revolutionaries. After several months of military confrontations between the Directory, in a civil war developed in Corrientes, Entre Ríos and the Oriental Province, the victory of Fructuoso Rivera in the battle of Guayabos in January 1815, forced the Supreme Director Carlos María de Alvear to evacuate Montevideo, handing it over to Artigas' deputy, Fernando Otorgués.

Alvear, determined to rule over the Río de la Plata provinces without opposition, offered Artigas the independence of the Oriental Province. Artigas rejected it and helped the federalists of Corrientes and Santa Fe to fight against the tutelage of the Directory, trying to impose a new form of state: federalism, which until then was foreign to the existing system in the Río de la Plata.

Artigas' victories facilitated the Fontezuelas uprising led by Ignacio Álvarez Thomas and the fall of Alvear on April 3 of that year. But relations with his successor, Supreme Director Álvarez Thomas, remained strained and violent. However, he did not try to bring his government back to the Eastern Province.

In May 1815, Artigas set up his Purification Camp, about one hundred kilometers north of the city of Paysandú, near the mouth of the Hervidero stream, which empties into the Uruguay River, and about seven kilometers from the so-called Meseta de Artigas. The Purification Camp was de facto transformed from the Federal League. Scottish merchant John Parish Robertson, who was visiting at the time, described the site thus:

He had about 1500 raging followers in his camp who acted in the double capacity of infants and riders. They were mostly Indians taken from the decayed Jesuit establishments, admirable horsemen and hardened in all kinds of deprivation and fatigue. The hills and fertile plains of the East Banda and Entre Ríos supplied abundant grass for their horses, and numerous cattle to feed. Little more needed. Jacket and a girded poncho in the waist as kilt Scots, while another hung from their shoulders, completed with the hat of fajina and a pair of boots of potro, big spades, sable, trabble and knife, the artichoke shorthand. His camp formed rows of leather awnings and mud ranches; and these, with a half dozen best-looking casuchas, constituted what was called Villa de la Purificación.

On June 29, 1815, the «Congress of Free Peoples» called the Eastern Congress met in Concepción del Uruguay, Entre Ríos. He was summoned by Artigas to discuss the arrangement with Buenos Aires in the belief that a Spanish naval expedition was about to arrive, but some historians maintain that in the inaugural session of June 29, 1815, a declaration of national independence of the provinces of Buenos Aires was made. Córdoba, Corrientes, Entre Ríos, Misiones, Santa Fe and the Eastern Province of any foreign power, although this position cannot be documented because the minutes of the congress —if there were any— would have been lost.

Artigas sent a delegation to Buenos Aires with the premise of maintaining unity based on the principles of: «The particular sovereignty of the peoples will be precisely declared and displayed, as the sole object of our revolution; the federal unity of all peoples and independence not only from Spain but from all foreign powers (...)». The four delegates were arrested in Buenos Aires, and the new director ordered to invade Santa Fe.

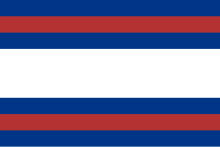

Artigas then ratified the use of the flag created by Manuel Belgrano, adding a diagonal festoon to it, since then the red punzó has been the sign of federalism in Argentina. Artigas called it "the Freedom Pavilion."

On September 10, 1815, this congress sanctioned a Provisional Regulation of the Eastern Province for the promotion of its campaign and security of its Landowners, which was the first agrarian reform in Latin America, since that he expropriated the land and distributed it among those who worked it "with the prevention that the most unfortunate are the most privileged".

Second marriage and other new children

It was also in the Purification Camp where José Artigas contracted his second marriage in December 1815 (his first marriage with Rosalía Villagrán had been annulled due to her dementia) with Melchora Cuenca, a Paraguayan spearwoman. This woman, much younger than Artigas, met the hero because her father brought food to Artigas sent by the Junta del Paraguay. As a result of the union, two children were born: Santiago (born in 1816) and María (born in 1819).

The Luso-Brazilian invasion and the war against the Unitarians

On July 9, 1816, the independence of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata was declared in the Congress of Tucumán, but in it, with the exception of Córdoba, the provinces belonging to the League of Peoples were not represented Free, who were under the authority of José Artigas.

The constant growth of influence and prestige of the Federal League frightened both the Unitarians of Buenos Aires and Montevideo as well as the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarve. In August 1816 numerous Luso-Brazilian troops invaded the Eastern Province, with the tacit complicity of the Unitarians who had strengthened themselves in Buenos Aires and the Buenos Aires ambassador in Rio de Janeiro. With the intention of destroying the caudillo and his revolution, the Luso-Brazilian troops attacked by land and sea. Together with Artigas, his lieutenants Juan Antonio Lavalleja, Fernando Otorgués, Andrés Latorre, Manuel Oribe, the missionary Andrés Guazurarí, nicknamed "the Indian Andresito", participated in the defense of his province. Due to their numerical and material superiority, the Luso-Brazilian forces under the command of Carlos Federico Lecor defeated Artigas and his lieutenants and occupied Montevideo on January 20, 1817, although the fight continued for three years in rural areas.. Outraged by the passivity of the Unitarians in Buenos Aires, Artigas declared war on them, while he confronted the Luso-Brazilians with armies that were decimated by successive defeats.

After three and a half years of resistance, the battle of Tacuarembó, on January 22, 1820, meant the final defeat of Artigas, who had to abandon the Eastern Province, to which he never returned. Several of his lieutenants were taken prisoner or abandoned the fight. Fructuoso Rivera, for his part, surrounded by the Portuguese-Brazilian army in his camp near the Queguay River, commanded by Bento Manuel Ribeiro, agreed to the pacification of the province, with the so-called Three Trees Agreement.

Conflict with Ramírez

At about the same time, the members of the Federal League, Francisco Ramírez, governor of Entre Ríos, and Estanislao López, governor of Santa Fe, finally achieved victory over the unitarios. The battle of Cepeda forced the fall of the Directory. But the hope did not last long, since both leaders, upon learning of the near annihilation of Artigas' troops, entered into agreements with the new Buenos Aires governor, Manuel de Sarratea, signing the Treaty of Pilar with him. Although such a treaty considered asking Artigas for his approval, the oriental considered himself affronted for not having been consulted by the signatories of the treaty.

After the battle of Tacuarembó, the defeated Artigas settled in Entre Ríos, where he entered into serious conflicts with Francisco Ramírez, who did not accept the hegemony of the eastern caudillo in his province. With the support of the Buenos Aires government, Ramírez began a campaign against Artigas. He was defeated in a small battle, but managed to defeat him in the battle of Las Tunas, near Paraná.

Ramírez pursued Artigas towards Corrientes, where he still had the support of the Guaraní chief Francisco Javier Sití. But the victory was, ultimately, for Ramírez.

From 1820 to 1850: exile in Paraguay

Surrounded on all sides by Francisco Ramírez's lieutenants and seeing his cause definitively lost, on September 5, 1820, José Artigas crossed the Paraná River into exile in Paraguay, leaving his homeland and family behind.

The Paraguayan dictator José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia gave him refuge, but took care that he did not retain any political influence, nor did he maintain any correspondence with anyone outside of Paraguay. His only companion for the rest of his life was Black Ansina.

The campaign of the Thirty-Three Orientals began the liberation of its province from the Empire of Brazil in 1825. But the complicated War of Brazil and the diplomatic interferences of Great Britain led to the independence of the Oriental State of Uruguay in 1828, in which Artigas never participated.

Confined to the distant and inhospitable Villa de San Isidro Labrador de Curuguaty, he lived there cultivating the land until the death of Rodríguez de Francia and did not cause any problems for the Paraguayan authorities. It was in this town where Artigas met Clara Gómez Alonso around the year 1825, who was his companion until his death; From this union Juan Simeón was born in 1827, the last of his long progeny and who became a lieutenant colonel in Paraguay, a trusted man of Marshal Francisco Solano López.

Despite his passivity in exile, as a mere precaution, he was arrested a few weeks after the death of the dictator, which occurred on September 20, 1840. The new government of Carlos Antonio López, Paraguay's first constitutional president transferred him to Asunción, where he enjoyed his placid old age in the Asunceno neighborhood of Trinidad, residing in the President of the Republic's own Quinta Ybyray, surrounded by the affection of the Paraguayans. There he died, ten years later, on September 23, 1850, at the age of 86.

Get my horse!Last words of José Gervasio Artigas.

On the same day, a cart without an awning, drawn by oxen, took his body from his ranch to the Recoleta cemetery, accompanied by Benigno López, the president's youngest son, the neighbors Julián Ayala, Alejandro García and Ramón de la Paz Rodríguez and the faithful assistant Ansina. The priest simply records in the book of the dead:

“In this Parroquia de la Recoleta de la Capital, on 23 September 1850, I, the interim priest of her, buried in the third tomb of the lance number 26 of the General Cemetery, the corpse of an adult named Don José Artigas, a foreigner, who lived in the understanding of this church”

The Paraguayans and Guarani from Misiones called him Karay Guazú (‘great lord’), a title they gave not only to Artigas, but also to Rodríguez de Francia and Francisco Solano López. On the other hand, the historian Gonzalo Abella mentions the nickname Oberavá Karay (lord who shines), a title with which the Guarani from the Curuguaty area referred to Artigas.

Testimony of his long stay in Paraguay are a public school and an ibirapitá tree.

Fate of his remains

In 1855, under the management of President Venancio Flores, the remains of José Artigas were repatriated from Paraguay.

Already in Montevideo they remained eight months in the Captaincy of the Port and were withdrawn on November 20, 1856 when they were buried in the National Pantheon of the Central Cemetery with the solemnity corresponding to the services rendered to their country, after The funeral obsequies will be held in the Mother Church. According to Joaquín Requena, they were buried "under the shadow of the Sacred Banner of the divine liberator of the human race" and the following inscription was read on their tombstone:

"Artigas: founder of Eastern nationality."

In 1859, while works were being carried out in the Central Cemetery, the remains were temporarily transferred to the family tomb of Artigas' relative, the former president of the Republic Gabriel Pereira. On January 24, 1864, the remains returned to the Central Cemetery and were deposited in the Rotunda of the Central Cemetery, whose construction had been completed the previous year.

In 1877 during the government of Lorenzo Latorre, the urn was exchanged for another made "of cedar wood veneered with jacaranda, inlaid with silver, with its corresponding pedestal."

In 1950, to celebrate the centenary of Artigas's death, the urn was placed on an altar located in the Obelisco of Montevideo to be exhibited.

In 1971, arguing that information had been obtained by which the urn was going to be stolen, a military operation was ordered by which the remains were transferred to the Blandengues de Artigas Cavalry Regiment No. 1, remaining in the custody of the Army.

By decree-law no. 14276 of September 27, 1974, the creation of a mausoleum for the deposit of his remains was established, which is located in the Plaza Independencia, in the center of the city of Montevideo. His remains were removed from the National Pantheon of the Central Cemetery in 1972 and were under the guard of the Army being guarded by the "softies", while the construction of the mausoleum was finished. They were transferred there on June 19, 1977.

The mausoleum was remodeled in 2010. On October 26, 2012, the remains of the hero were finally returned to their home, in a public ceremony that included a speech by Professor Daniel Vidart.

Profile

José Artigas had an outstanding performance in the Spanish-American wars of independence and in the predominance of republican ideas over monarchical ones. He fought successively against the Spanish Empire and the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarve and against the Unitarios of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, both from Buenos Aires and Montevideo.

Artigas was oriental, understanding as such the inhabitant of the Banda Oriental of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, which was made up of what is now Uruguay and part of the current Brazilian state of Río Grande do Sul. Directly, his struggles were oriented to the formation of the Federal League, organized strictly on the principles of the republic and federalism. The Federal League was joined, in addition to the Oriental Province, by the provinces of Córdoba, Corrientes, Entre Ríos, Santa Fe and the towns of Misiones under the control of Andresito Guazurarí, all of them currently part of the Argentine Republic, at that time the Provinces United States of the Río de la Plata.

His strong defense of the federal autonomy of the provinces indirectly contributed to the independence from Spain of the territories that made up the Federal League. In 1828, at the end of the Brazilian War, part of the Eastern Province —the north remained in Brazilian power— became an independent state from the rest of the Argentine provinces, emerging the Eastern State of Uruguay, when Artigas was already in his long exile in Paraguay, the country where he died. In other words, Artigas never considered the Banda Oriental as an independent country, nor did he ever call it Uruguay.

Legacy

The roots of José Artigas' ideology have two main sources. As a teenager, Artigas read books from Europe and the United States, such as Thomas Paine's Common Sense and Rousseau's The Social Contract, among others by Enlightenment authors.

He was educated in a Franciscan Catholic school, from which he retired to his father's ranch, which was located on the lands bordering the Villa de Casupá. In the first stage of his life he was not influenced by revolutionary ideas. His education was not very orthodox although he did show brilliance in his performance. Chroniclers of the time say that at the time of his Purification Camp, in which he had three or four secretaries, he dictated letters to all four simultaneously, with surprising lucidity, in which he dealt with administrative and political organization, passing through for diplomatic letters and minor matters such as restitution of property to common people, or setting pensions for widows and children of their combatants killed in action. From his involvement with the campaign he gained experience for the revolution that he later carried out.

In the opinion of researcher Carlos Maggi, what marked Artigas in his adolescence was his relationship with indigenous people, blacks and gauchos. His roots, his avidity, what he read and his contact with Montevidean high society and with the marginalized part of society were mixed.

The artiguista ideology was made up of political ideas, which were expressed in the Instructions of the year XIII and in the formation of the Federal League. He also had socioeconomic ideas, which were expressed in the Land Regulation, the Provisional Regulation of the Eastern Province for the promotion of his campaign and the security of his Landowners, and the Provisional Regulation of Customs Tariffs for the Confederate Provinces of the Eastern Band of Paraná.

Tributes

Several countries honor Artigas.

- In Uruguay, the flag of the Federal League was adopted as one of its patriotic symbols, under the name of Artigas Flag. In addition, the Department of Artigas was established in its honor, whose capital is the City of Artigas.

Several hymns have also been dedicated to him, entitled "Himno a Artigas".

- In Argentina, Artigas is considered one of the hero commanders of the Argentine War of Independence and the creator of the Rio de Janeiro federalism, for these reasons the same flag of Artigas is now official in the Argentine province of Entre Ríos, and that of Misiones has its flag inspired by Artigas.

In most of the main Argentine cities there are monuments to Artigas or streets and even neighborhoods (such as "General Artigas", in Córdoba and, distant from that neighborhood, the monument to J. G. Artigas at the entrance to the Sarmiento Park); in Santa Fe, capital of the homonymous province, you can see a monument to Artigas at the roundabout at the intersection between Costanera and Javier de la Rosa avenues; as well as in the cities of Entre Ríos there are monuments that commemorate him, such as Concepción del Uruguay and Concordia with squares and streets named after him.

By decree-law 1255 of 1955, the Argentine government ordered the construction of a monument to Artigas in the Plaza República Oriental del Uruguay, in the conspicuous neighborhood of La Recoleta. It was built by the sculptor José Luis Zorrilla de San Martín and by the architect Alejandro Bustillo, inaugurated in April 1973.

In the Parque Tres de Febrero, in the city of Buenos Aires, since 1910 Artigas has been honored by a shoot of the ibirápitá that was found in its last resting place (the Asuncena). Since June 10, 2013, the National Route 14 bears the name of Artigas.

- In Asunción de Paraguay, it bears its name an important avenue that culminates in the Botanical Garden, where is the "Artigas" school, where the procer spent his last years in exile.

Also in Asunción, on November 8, 2002, a monument to Artigas was inaugurated in Plaza Uruguaya.

- In Chile, in Santiago de Chile, there is a statue in his honor on the central side of the Alameda del Libertador Bernardo O'Higgins, between the streets of 18th and San Ignacio.

- In Mexico on Plaza Uruguay, located between Avenida Masaryk and Calle Juana de Ibarbourou, in the Polanco colony, there is also a statue of the general and, at the foot, several of his famous phrases.

- In the United States there are Artigas statues on Constitution Avenue in Washington D.C., on the Sixth Avenue of Manhattan (between Broome St. and Dominick St), Newark (New Jersey) and Montevideo (Minnesota).

- In Spain there is a statue of his in the park of the West of Madrid, being a work of the sculptor Juan Luis Blanes, who in turn copied from the Santiago de Chile, and was donated by the Uruguayan embassy to be installed in this location in 1975.

- In Ecuador, in Quito there is a square called "Plaza Artigas" with a statue of it. In Guayaquil there is also a statue of José Artigas donated by the Eastern Republic of Uruguay.

Movies

- 1950: José Artigas, protector of the free peoples. Documentary directed by the Italian Enrico Gras.

- 2006: The little herodirected and guided by Roberto Bayeto. Animation film on the childhood of the hero.

- 2011: Artigas - La Redota, directed by César Charlone, produced by Sancho Gracia, with Jorge Esmoris on the leading role.

- 2017: The escape of Artigas Documentary directed by Fabián González. Drama on the desertion of Artigas of the Spanish forces.

In art

Contenido relacionado

Mobutu Sese Seko

Franz von papen

Antonio de Guill y Gonzaga

Manuel Maria de Llano

Raul Alfonsin