Jose Bernardo de Tagle

José Bernardo de Tagle y Portocarrero (Lima, March 21, 1779-Callao, September 26, 1825), noblemanly IV Marquis of Torre Tagle, better known as Torre Tagle, was a Peruvian soldier and politician, who ruled the Republic of Peru in four periods, between 1822 and 1824. He was the second president of Peru.

From a very young age, he became involved in circles that conspired in favor of independence, despite belonging to the Creole nobility. He was mayor of Lima from 1811 to 1812. He traveled to Spain, and upon returning, he was appointed by Viceroy Joaquín de la Pezuela as Mayor of Trujillo, where he openly joined the patriot cause, proclaiming the Independence of Trujillo on December 29, 1820 in the northern city. Established the government of the Protectorate headed by the Liberator José de San Martín, he was entrusted with various military and administrative functions. With regard to the supreme command, he was first Supreme Delegate temporarily replacing San Martín when he went to meet with Bolívar in Guayaquil, in 1822; then he was Charged with Supreme Power, for one day, after the overthrow of the Supreme Government Junta in February 1823; later he was Charged with the Supreme Command on the eve of the arrival of the Liberator Bolívar, from July to August 1823; and he was immediately appointed by Congress as President of Peru, being him the second citizen to assume said title (the first was José de la Riva Agüero), while Bolívar exercised military power. Accused of conspiring in favor of the Spanish, he was stripped of command in February 1824 and took refuge in the Real Felipe Fortress, the last royalist bastion besieged by the patriots, where he died of scurvy.

Early Years

He was born in Lima on March 21, 1779, into an aristocratic Creole family. His parents were: José Manuel de Tagle e Isásaga, third Marquis of Torre Tagle, Knight of the Order of Carlos III, and Josefa de las Mercedes Portocarrero y Zamudio. His father was the grandson of José Bernardo de Tagle Bracho y Pérez de la Riva, Viscount of Bracho, who obtained the Marquisate of Torre Tagle in 1730, and his mother was the great-granddaughter of Melchor Portocarrero Lasso de la Vega, Viceroy of Peru, and a descendant of the Judeoconversos Of the Cavalry.

His early studies were taught by private teachers. He joined the Dragoon Regiment , working in his ranks as a script holder (1790). He took his main studies at the Real Convictorio de San Carlos, later part of the University of San Marcos.

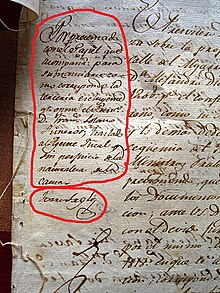

In 1801 his father died, becoming the fourth Marquis of Torre Tagle, and inheriting at the same time the position of commissioner of War and Navy of Callao, but only a provisional letter was issued of his noble title (December 3, 1810), since the pending payments for lances and half anatas required that he request confirmation from the Council of the Indies. With his paternal inheritance, he found himself possessing a great fortune and settled in his superb mansion on San Pedro street, with great luxury and splendor.

Promoted to sergeant major, he went to the Regiment of Distinguished Volunteers of the Spanish Concord of Peru, whose brilliance and discipline he provided with his own money, and for this reason he was successively promoted to lieutenant colonel and colonel (December 3, 1812). He simultaneously served as ordinary mayor of Lima (1811-1812).

Stay in Spain (1812-1817)

By then he was closely linked to conspicuous liberals such as José Baquíjano y Carrillo, José de la Riva Agüero y Sánchez Boquete and the Count of Vega del Ren, for which reason Viceroy José Fernando de Abascal considered it convenient to remove him from the country; and for this he propitiated the election of him as deputy to Cortes for the province of Lima (March 29, 1813). He then undertook a trip to the Iberian Peninsula, passing through Panama, Havana and finally arriving in Cádiz. In the famous Assembly or Cortes of Cádiz he recognized the need to work for the independence of America. He was invested with the habit of a knight of the Order of Santiago (1815), promoted to Brigadier of Infantry (May 2, 1815) and favored by the King of France Louis XVIII with the Fleur de Lis (April 7, 1816)..

Liberator of the Municipality of Trujillo (1820-1821)

Appointed mayor of La Paz (present-day Bolivia), he traveled back to America, but upon arriving in Lima (July 21, 1819), Viceroy Joaquín de la Pezuela did not want to give him that position because he was already in it his friend Juan Sánchez Lima; in return he assigned him to his cabinet as aide-de-camp, and then provisionally entrusted him with the Trujillo Intendancy, in northern Peru. Apparently satisfied, Torre Tagle assumed his functions on August 25, 1820, but secretly contacted General José de San Martín and the Liberating Expedition, and surprisingly proclaimed independence in the city of Trujillo (December 29, 1820). The importance of this event was transcendental for the Peruvian emancipatory process since without major violence, an extensive region of the north of the Peruvian Viceroyalty was definitively won over to the independence cause.

Torre Tagle's attitude was not unique since both in the crucial stage of independence and in the early years of the Republic, Trujillo's aristocrats played leadership roles.

In Trujillo, Torre Tagle continued to actively support the patriot cause: he worked in the formation of military corps and the collection of supplies, he contributed to quelling the reactions attempted by the royalists in some towns in his jurisdiction. In August 1821 he returned to Lima and was appointed General Inspector of the Civic Guards and later Commander of the Peruvian Guard Legion. Appointed State Councilor (October 8, 1821), he was incorporated into the Order of the Sun with the title of Founder (December 12, 1821). He was promoted to Field Marshal (December 22, 1821), and was authorized to exchange his noble title for that of Marquis of Trujillo (January 15, 1822), in honor of his contribution to the cause of independence with his pronouncement in that city.

Supreme Delegate (1822)

When the Protector San Martín traveled to meet with the Liberator Simón Bolívar in Guayaquil, Tagle was in charge of the Executive power as Supreme Delegate (from January 19 to August 21, 1822). He carried out his functions with the equanimity that the case required, but he could not prevent exalted republicanism from spilling over to obtain the expulsion of the hated Argentine minister Bernardo Monteagudo. Perhaps Tagle felt a great relief when San Martín returned to Lima and resumed the heavy work of government, and he, for his part, was able to return to his calmer work as inspector of the civic guards. The River Plate Libertador had no qualms about describing him, some time later, as "weak and inept."

Government Work

As Supreme Delegate, Tagle gave provisions to renew the design of the Peruvian national flag, since the one outlined by José de San Martín was very difficult to elaborate. By decree given in Lima on March 15, 1822, he ordered the following:

The national flag of Peru will consist of a cross-sectional white (horizontal) strip between two incarnated in the same width, with a Sun also incarnated on the white strip; the preferred badge will be all incarnated with a white Sun in the center; and the banner will be equal in everything to the flag with the difference of the provisional weapons of the State that will be embroidered on the center of the white strip.

However, the new model of the Peruvian flag brought serious drawbacks due to its relative resemblance to the Spanish flag (red and gold, with horizontal stripes). It was said that a patriot regiment was beaten when approaching a royalist squadron, believing it to be friendly forces. Due to this, by decree of May 31 of the same year, 1822, Torre Tagle renewed the designs of the flag and banner:

"The flag of warships, sea squares and their castles will be three vertical or perpendicular lists, the one in the white center, and those of the ends incarnated with a sun also incarnated on the white list... The banner will be equal in everything to the flag, with the difference that instead of the sun, will carry the provisional weapons of the embroidered state over the center of the white list."

This design of the Peruvian national flag (also called the bicolor ensign or the “blanquirroja”) is the one that has persisted to this day, except for the incarnated sun that was eliminated.

In charge of the Supreme Power (February 1823)

Shortly after, San Martín withdrew from Peru and the powers of the State were assumed by Congress, which granted executive power to a Supreme Governing Board chaired by José de La Mar (September 21, 1822). When this Junta ceased (February 27, 1823), Torre Tagle was called to occupy the supreme power for being the highest-ranking officer, although he was only there momentarily, because the next day José de la Riva Agüero y Sánchez Boquete took over as First President of the Peruvian Republic, elected by Congress. This new government failed in its attempt to culminate the Peruvian war of independence through the so-called Second Intermediate Campaign and there was then a general feeling to call Bolívar and his Gran Colombian liberation army.

President of Peru (1823-1824)

On the eve of Bolívar's arrival in Peru, Torre Tagle was once again called to take charge of the supreme command of the Republic (July 17, 1823), by express orders of the Venezuelan general Antonio José de Sucre (lieutenant of the Liberator)., who gave him the political power he had until then by virtue of the powers that the Peruvian Congress had conferred on him.

Torre Tagle once again assumed power provisionally; On August 6, he was reinstated by Congress, which recognized him as Supreme Chief, and finally, on August 16, Congress itself invested him as President of the Republic, replacing the already ousted Riva Aguero. He was later ratified as Constitutional President according to the terms of the liberal Constitution that had just been promulgated (November 18, 1823). He thus formally became the second President of Peru. As vice president, he was accompanied by the Lima nobleman Diego de Aliaga.

Bolívar arrived in Peru on September 1, 1823, to end the war against the royalists still concentrated in central and southern Peru. He recognized the government of Torre Tagle and the Congress meeting in Lima, but assumed in his person the supreme military and political authority in the entire Republic that the same Congress granted him on September 10, 1823. But before undertaking the fight against the royalists, he opened a campaign against Riva Agüero and his supporters, who had concentrated in Trujillo constituting a parallel government. But fortunately the civil war did not break out as Riva Agüero and his main supporters were arrested and deported abroad. Bolívar then returned to the Lima region; In Pativilca he established his headquarters and from there he outlined the plans to achieve full independence for Peru.

Negotiations with the Spanish

With the intention of buying time, Bolívar ordered Torre Tagle to enter into negotiations with the royalists to see the possibility of agreeing to an armistice. Congress approved the idea and the Minister of War Juan de Berindoaga, Viscount of San Donás, was appointed negotiator. He was to negotiate peace on the basis of the recognition of the independence of Peru. Berindoaga arrived at the royalist camp in Jauja (Peru's central highlands), where he met with Generals Juan Loriga and Juan Antonio Monet, and with Brigadier Andrés García Camba; he then wanted to go to Huancayo to meet José de Canterac, but he refused to receive him. Berindoaga considered his mission finished, without achieving his mission, and returned to Lima. There Tagle secretly confided to him (February 3, 1824) that he had just discovered that Diego de Aliaga, his vice-president, had sent José Terón, a spirits merchant, to Ica on his own account, carrying a communication to the royalists informing them that both – Aliaga and Tagle– were on their side. There was also mention of a plan to establish a shared government or Triumvirate that would be made up of Tagle, Aliaga and Viceroy La Serna. In other words, according to Tagle's version, his name had been used without his consent to involve him in a betrayal of the patriot cause. The truth is that, even knowing such maneuvers, Tagle decided to hide them, so even though his innocence could be true, he became an accomplice. However, it is more likely that Tagle, fed up like many other Peruvian patriots with the arrogance of Bolívar and the Gran Colombian forces (who acted as occupation forces on Peruvian soil and committed looting and looting), entered into secret negotiations with the royalists to end the war. war on the basis that Bolívar left Peru, negotiations that would not necessarily have to imply submission to Viceroy La Serna or blind obedience to the King of Spain, but an understanding that would have as its ultimate goal the recognition of the independence of Peru. Everything indicates that until that moment, Tagle remained loyal to the cause of emancipation.

Government work

During this period of government, he took, among other measures, the following:

- He reinstated the Congress that had been dissolved by his predecessor José de la Riva Agüero and Sánchez Boquete (6 August 1823). Despite its flaws, Congress then emerged as the sole representative of sovereignty and the sole source of legitimacy. They were part of him personalities of the size of José Faustino Sánchez Carrión, Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza, Manuel Salazar and Baquíjano, José de La Mar, Hipólito Unanue, Justo Figuerola, among others. Its immediate task was the culmination of its constituent work, that is, the text of which would be the first political letter of the Peruvian Republic.

- He agreed that the Congress would grant Bolivar military and political authority throughout the territory of the Republic, with great powers, under the name of Libertador. He had to agree with Bolivar in all cases of his natural attribution and that they were not in opposition to the powers granted to the Liberator (September 10, 1823). As an irrisory compensation for this diminishing power, the Congress awarded Tagle a medal under the name "Restorship of Sovereign Representation".

- It promulgated the Liberal Constitution of 1823 (12 November 1823), the first in Peru. It was divided into three sections devoted to the Peruvian nation, territory, religion and citizenship; the form of government and the powers that formed it; and the means of preserving the government. It should be noted that one day before this promulgation, the Congress itself declared that it suspended compliance with the constitutional articles incompatible with the powers given to Bolivar. So, in practice, the 1823 Constitution was not even a single day in force during the Tagle government. Only after the fall of the Bolivarian regime in 1827 was replaced, to last ephemerally, by being replaced in 1828 by another Constitution.

Fall and death

On February 5, 1824, an uprising occurred in the castles of Real Felipe del Callao by troops from the River Plate that garrisoned said plaza. Royalist troops from the mountains advanced towards Lima to support the rebels. Faced with the danger, Bolívar ordered the evacuation of the city, and by decree of February 10, 1824, Congress granted dictatorial powers to the Liberator. Thus officially ended the presidency of Torre Tagle, whose limited power had otherwise been only nominal. Shortly after, the royalists occupied Lima and Callao.

Bolívar believed that Tagle and Berindoaga had been compromised behind the uprising in the Real Felipe del Callao Fortress and his delivery to the royalists, and he ordered them to be captured and put on trial. Torre Tagle remained hidden for several days in a Mercedarian monastery in Lima, since he was sure that Bolívar would shoot him without further ado. When the royalist general Juan Antonio Monet occupied Lima (February 29, 1824), Tagle decided to surrender to said chief, declaring in writing that:

If the Spanish authorities, as I hope, are willing to recognize the independence of Peru, I will second the ideas on that basis... But if this proposal does not adapt to his calculations, my position demands that he be reputed as a prisoner of war...(3 March 1824).

But, to his surprise, not only was he not treated as a prisoner, but the rank he had held in the royalist army was recognized, an honor guard was placed in his house and he was offered the civil command of the city. Torre Tagle had the discretion not to accept this position. A few days later he published a manifesto where he narrated, from his point of view, what happened between him and Bolívar, as well as the latest events of his unfortunate administration. He also made known his disappointment in the cause of independence, declaring himself a faithful subject of the King of Spain, a dramatic turn on his part, even more so having worked so intensely for the emancipatory cause (March 6, 1824)..

When the royalists withdrew from Lima at the beginning of December, Torre Tagle took refuge in the Real Felipe del Callao Fortress, the last nucleus of Spanish resistance in Peru. He was accompanied by his wife and his younger children. He wanted the Chilean government to grant him asylum and for this purpose he wrote a letter to Rear Admiral Manuel Blanco Encalada asking him to welcome him on one of the squadron's ships. But Blanco Encalada limited himself to sending the letter to Bolívar. The Callao fortress was besieged, and thus, in the midst of the most appalling conditions, Tagle died of scurvy (September 26, 1825). His wife and one of his children met the same tragic end.

He was buried next to his wife in the Presbítero Matías Maestro Cemetery until December 27, 2020, where he was taken to the crypt of the Trujillo Cathedral (Peru) with his wife in the framework of the Bicentennial of the Independence of Trujillo. In his will he bequeathed his assets to his three surviving children.

Family

Ancestors

Ancestors of José Bernardo de Tagle | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Marriage and offspring

In 1800, despite family opposition, he married Juana Rosa García de la Plata y Orbaneja, daughter of the Spaniard Manuel García de la Plata y Miñandres, who was a judge of the Royal Court of Lima.

His wife, with whom he had no children, died in 1811 and the marquis married a second time, in 1819, with María Ana Micaela de Echevarría and Santiago de Ulloa in the church of the Tabernacle of the Cathedral of Lima.

From his second marriage, Torre Tagle had four children: Ana Josefa Cipriana (b. 1820), Josefa Manuela Felipa (b. 1822), María Manuela de la Asunción (b. 1823) and José Manuel Apolinario (b. 1824). The only man died in 1832 and one of the women became a religious. The only one who had children was Josefa, who inherited the title from her father in 1864 and married first Manuel Ortiz de Zevallos y García and then José Moreyra y Abella-Fuertes.

Among the prominent descendants of the IV Marquis, through his daughter Josefa, were Ricardo Ortiz de Zevallos y Tagle, VI Marquis of Torre Tagle; Javier Ortiz from Zevallos Thorndike; Gonzalo Ortiz de Zevallos Roedel; Felipe Ortiz de Zevallos Madueño; Emilio Ortiz de Zevallos and Vidaurre; Claudia Ortiz de Zevallos Cano; and Carlos Ortiz de Zevallos and Paz-Soldán.

Trials

Bolivarian historiography has execrated the memory of the Marquis of Torre Tagle, branding him a coward and traitor. But this severe judgment has the inevitable human error of limiting itself to the last performance of the character, without looking at his complete trajectory, as well as not taking into account the context of the facts.

The writer José de la Riva Agüero y Osma (great-grandson of the hero), says that Tagle "because of the extraordinary and extremely random circumstances in which he found himself is more to be pitied than execrated." Whatever Tagle's latest mistakes may have been, Peru and America in general owe him the most eminent service of having added, in December 1820, the extensive administration of Trujillo (northern Peru) to the cause of independence, without the need for bloody battles. An extensive and rich territory that would later become the supply base for Bolívar's liberating army, from where the campaign in the mountains began that would culminate in the victories of Junín and Ayacucho.

As for the Viscount of San Donás, Juan de Berindoaga, the writer Riva Agüero states bluntly that Bolívar shot him "not for treason but for black revenge." The historian Vargas Ugarte asserts for his part that "Berindoaga had always acted as a good citizen and the accusation of traitor was not consistent." In the person of the viscount, Bolívar tried to punish the Lima aristocracy, which was adverse to him. The execution of Berindoaga, like the delivery of the Venezuelan hero Francisco de Miranda to the Spanish, must be counted among the black pages of the Liberator.

Torre Tagle Palace

The former mansion of the Marquises of Torre Tagle, located in the Ucayali street, near the church of San Pedro, is preserved in Lima. It is one of the architectural monuments of Lima from the colonial era that stands out the most for its beauty and proportions. Since the 1920s it has been the seat of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Peru and is known as the Torre Tagle Palace.

It was built at the beginning of the 18th century by José Bernardo de Tagle y Bracho, who in 1730 was granted the title of first Marquis of Torre Tagle by King Felipe V of Spain. Born in Santander, he had a meritorious military career that led him to participate in many expeditions on the continent, finally being designated Perpetual Paymaster of the Royal Navy in Callao. He was married to Juliana Sánchez and on his death he was succeeded to the property of the historic house by Tadeo de Tagle y Bracho, José Manuel de Tagle Isasaga and José Bernardo de Tagle y Portocarrero, President of the Republic and 4th Marquis of Torre Tagle, who inherited his daughter Josefa de Tagle y Echevarría, who married Don Emilio Ortiz de Zevallos. The children of this marriage inherited the property, which the State bought by public deed on June 27, 1918 for the premises of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, paying the price of 320 thousand soles. The house has an asymmetric façade with a doorway carved in stone, in the upper part of which stands out the coat of arms of the Torre Tagle family, on which the legend reads: "Tagle was called who killed the serpent and married the infanta".

Contenido relacionado

Politics of Afghanistan

Church of rome

Anne Boleyn