Jorge manrique

Jorge Manrique (c. 1440-1479) was a pre-Renaissance poet and Castilian man of arms and letters, member of the House of Manrique de Lara, one of the oldest families in the Castilian nobility, and nephew of the poet Gómez Manrique. He is the author of the Coplas a la muerte de su padre, one of the classic poems of Spanish literature of all time. He has also composed various love and burlesque poems and is considered one of the most important poets within the General Songbook.

Biography

It is believed that Jorge Manrique was born in Paredes de Nava, in the current province of Palencia, although it is also possible that he was born in Segura de la Sierra, in the current province of Jaén, which at that time was head of the encomienda that he administered the master Rodrigo Manrique, his father. No specific document certifying his birth in either of the two towns has been preserved. 1440, the year in which Rodrigo Manrique acquired the lordship of Paredes de Nava, has been confused with the year of Jorge Manrique's birth and, therefore, the Palencia hypothesis has been given greater truth.

It is usually stated that he was born between the second half of 1439 and the first half of 1440. But the only certain thing is that he was not born before 1432, when his parents' marriage was arranged, nor after 1444, when Rodrigo Manrique, Mrs. Mencía de Figueroa, mother of Jorge Manrique and a native of Beas, died and had to request an apostolic dispensation to remarry due to her status as a knight of the Order of Santiago.

In the Crown of Castile Jorge was an infrequent name and none of his ancestors had been called that. That is why the choice of this name is curious, possibly linked to Rodrigo Manrique's close relationship with the Infantes of Aragon, the kingdom whose patron saint is Saint George.

His childhood and early youth were most likely spent in Siles and Segura de la Sierra. Rodrigo Manrique had a decisive role in the life of the poet and tried, through his education, to make him in his image and likeness. He studied Humanities and the tasks of the Castilian military and assumed the line of political and military action of his extensive Castilian family. He fought the Muslims, participated in the uprising of the nobles against Enrique IV of Castile, took part in the victory of Ajofrín and fought in favor of Isabella and against Juana la Beltraneja in the war of the Castilian succession.

His father, Rodrigo Manrique, Count of Paredes de Nava, and short-lived Master of the Order of Santiago since 1474, was one of the most powerful men of his time. He died at the age of seventy, in 1476, a victim of cancer that disfigured his face. His mother, Mencía de Figueroa, first cousin of the Marqués de Santillana, died when Jorge was a child. His uncle, Gómez Manrique, was also an eminent poet, as well as a playwright, and there was no shortage of other men of arms and letters in his family. The Manrique de Lara family was one of the oldest noble families in Spain and held some of the most important titles in Castile, such as the Duchy of Nájera, the County of Treviño and the Marquesado de Aguilar de Campoo, as well as various positions ecclesiastics.

Jorge Manrique married Doña Guiomar de Castañeda, his stepmother's young sister, possibly in 1470. Guiomar came from the most notable family in Toledo and the marriage occurred more for economic interests than for romantic reasons. The marriage had two children, Luis and Luisa.

At the age of 24, he participated in the fighting in the siege of the castle of Montizón (Villamanrique, Ciudad Real), where he gained fame and prestige as a warrior. His motto was "I neither lie nor regret." He remained a prisoner in Baeza for a time where his brother Rodrigo de él died, after his military entry into the city to help his allies, the Benavides, in front of the royal delegates (the count of Cabra and the marshal of Baena). He later enlisted with the troops on the side of Isabel and Fernando in the war against the supporters of Juana la Beltraneja. As a lieutenant of the queen in Ciudad Real, together with his father Rodrigo de él, he lifted the siege that Juan Pacheco and the Archbishop of Toledo Alfonso Carrillo de Acuña had placed on Uclés. In that war, in a skirmish near the castle of Garcimuñoz in Cuenca, defended by the Marquis of Villena, he was mortally wounded in 1479, probably around spring. As with the birth, there are different versions of the event: some contemporary chroniclers such as Hernando del Pulgar and Alonso de Palencia testify that he died in the same fight, in front of the castle walls, or just afterward. Others, such as Jerónimo Zurita, later maintained (1562) that his death took place in Santa María del Campo Rus (Cuenca), where his camp was, days after the battle. Rades de Andrada pointed out how two verses were found among his clothes that begin «Oh world!, because you kill me...». Pedro de Baeza, leader of the Marqués de Villena's army in Castillo de Garcimuñoz, wrote that the campaign in the Castillo de Garcimuñoz lasted five months and that the poet died "at the end of it." The most correct versions of his death are those given by Pedro de Baeza and the residents of Castillo de Garcimuñoz in the Relations of towns of the bishopric of Cuenca, according to which he was wounded when he came loaded with loot and Pedro de Baeza set him up in a trap. the proximities of Castillo de Garcimuñoz on the path of La Nava. It is estimated that the warfare began in November or December 1478 and, according to Derek Lomax, he died in April or May 1479. According to Uclés's obituary, he died on April 24, 1479. He was buried in the Uclés monastery, head of the order of Santiago at the foot of his father's grave. The Castilian war ended a few months later, in September.

Lord of Belmontejo de la Sierra (now Villamanrique), commander of the castle of Montizón, Trece de Santiago, Duke of Montalvo by Aragonese concession and captain of men-at-arms of Castile, was more a warrior than a writer, despite which He was also a distinguished poet, considered by some to be the first of the Pre-Renaissance. In his poetry, the Spanish language leaves the Court and the monasteries to meet the individual author who, faced with a transcendental event in his life, summarizes in a work all the feelings of his short existence and saves for posterity not only his father as a warrior, but himself as a poet.

Works

Minor poems

His poetic work is not extensive, approximately 50 compositions, including most of them in the General Songbook (1511). He is usually classified into three groups: loving, burlesque and doctrinal, of which loving is the one with the most compositions, some of them erotic. They are, in general, satirical and conventional love works within the canons of song poetry of the time, still under Provencal influence, with a tone of erotic gallantry veiled by means of fine allegories. Manrique complies with the linguistic conventions of Provençal poetry: use of song and saying, in octosyllabic verse, use of repetitions of words and use of war as a love simile.

In his love compositions, Manrique uses clichés, themes, poetic resources and vocabulary typical of courtly love, like other poets of the 15th century. That is why the wounds of love, the desire of the vassal and the rejection of the lady are present in his verses.

Jorge Manrique is not original in these compositions, since he takes troubadour lyric as a model. There is not much presence of poems that speak of personal love experiences, so this is a poetry of more historical and literary value than a sample of the poet's intimate feelings.

Among these compositions, the following stand out: Of the profession he made in the Order of Love, in which he speaks metaphorically of a religious order to show devotion to his beloved (vows of poverty, obedience); Love Scale, which represents the love relationship as something that must be cared for and defended; and Castillo de Amor , where the lady stands out for her good qualities and her lover admires all her virtues as occurs in courtly love. It is not surprising that in his burlesque compositions irony is much stronger and more shameless than in love ones. Mockery is unrefined humor, it's poignant and hurtful humor, much coarser than simple, mild irony.

Jorge Manrique's burlesque poetry includes three poems. The first of them is To a cousin of hers who was getting in the way of some love affairs with only nine verses. The grace of this poem is the double meaning that the word prima has, which can refer to the string with the highest timbre of an instrument or be understood as a family string. What Manrique does in these verses is compare a cousin of his who did not want to reciprocate his love desire with the string of the same name that is out of tune. Another of the poems by this satirical group is Songs to a beuda who had pawned a brial in the tavern where Manrique ridicules a woman who, in order to continue getting drunk, gives her cloak (brial) to her change her Manrique takes the time to criticize this woman because she discovers that she is speaking ill of him. Lastly, A conbite that he made to his stepmother : this poem stands out for being the longest of the three, it has one hundred and twenty verses. It was probably written after 1476 and it clearly shows the relationship that Don Jorge had with his stepmother and at the same time his sister-in-law, Elvira de Castañeda, third wife of his father, Rodrigo Manrique and, in turn, his wife's sister. Guiomar de Castañeda. In this composition he talks about the party that he threw in honor of his stepmother, in which both the place, the attendees and the food are dirty and give a generally grotesque and unpleasant image. It is clear that Jorge Manrique did not have much respect for his stepmother.

The two compositions dedicated to his wife must be from the time of their marriage, around 1470; the Coplas, from the summer of 1477; and the Posthumous Verses will be, according to the rubric that accompanies them, from shortly before her death.

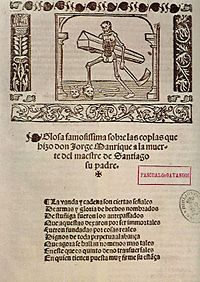

Coplas for the death of his father

Among all his work, the Coplas for the death of his father stand out in a distinctive way for uniting tradition and originality. In them Jorge Manrique makes the funeral eulogy or planting of his father, Rodrigo Manrique, showing him as a model of heroism, virtues and serenity in the face of death. The poem is one of the classics of Spanish literature of all time and has passed into the canon of universal literature.

The Coplas were written just after the death of Rodrigo Manrique and were first published posthumously, between the years 1480 and 1490, in Zamora or Zaragoza. The oldest surviving testimony comes from the Baena Songbook, therefore it could not have been the manuscript that Juan Alfonso gave to Juan II. They were glossed by innumerable authors, they deserved the honor of a Latin translation, and their influence is felt in later great authors.

In them the theme of death progresses from the general and abstract to the more concrete and human: the death of the author's father. Normally one speaks of a division into three parts. The first part covers the first fourteen stanzas and consists of an introduction in a moralizing tone about the low value of earthly life, death and its omnipotence. In the second part, from stanzas fifteen to twenty-four, mention is made of the death of famous people from the recent and near past. The third and last part, from stanzas twenty-five to forty, is devoted to extolling the figure of Rodrigo Manrique by comparing it with that of great figures of Roman times to highlight its virtues, culminating the work with a dialogue between him and Death..

Manrique outlines the existence of three lives: the human and mortal one, the one of fame, which is longer, and the eternal one, which has no end. The poet himself saves himself and his father through the life of fame that not only his virtues as a Christian knight and warrior grant him, but also through the poetic word, as the poem concludes:

Let's get some comfort.

his memory.Coplas for the death of his father, vv. 479-480.

It is about the memory that his son leaves in these couplets and that serves to save both the warrior father and the poet son for posterity.

The metric adopted, the couplet of broken foot, lends to the poem, according to Azorín in Al margin de los clásicos, a great sententiousness and a brittle and funereal rhythm like the funeral ringing of a Campaign. The biblical inspiration comes from Ecclesiastes and the Moral Commentaries to the Book of Job of Saint Gregory. It also resonates with the fatalism of the medieval clichés of ubi sunt?, vanitas vanitatum, homo viator. A critical edition of Vicenç Beltrán's Coplas is currently available. Egerton and Oñate-Castañeda, as well as the first editions, those of Pablo Hurus and Antón de Centenera. They were glossed by countless authors (Alonso de Cervantes, Rodrigo de Valdepeñas, Diego Barahona, Jorge de Montemayor, Francisco de Guzmán, Gonzalo de Figueroa, Luis de Aranda, Luis Pérez and Gregorio Silvestre) and even deserved the honor of a Latin translation. His influence is felt in great poets such as Andrés Fernández de Andrada, Francisco de Quevedo or Antonio Machado. They were translated into French, among others, by Guy Debord, the influential author of The Society of the Spectacle, as Stances sur la mort de son père

The metric resources of his poetry prefer brief forms over vast compositions called decires. The rhyme is sometimes not very careful. He does not abuse cultism and prefers plain language over poets like Juan de Mena and the Marquis de Santillana and, in general, the lyrical cancioneril of his time; This is a trait that quite individualizes the author at a time when the courtly presumption made the cancioneril lyricists exhibit his ingenuity through a premature conceptism or demonstrating his knowledge with the Latinization of the allegorical-Dante school.

Jorge Manrique's style heralds Renaissance clarity and balance. The expression is flat and serene, accompanied by similes, as is typical of the sermo humilis or humble style, the natural and common style of didactic literature. There are even vulgarisms, which provide an air of simplicity and sobriety, and which makes it fit perfectly into the rhetorical techniques and puns typical of the 14th century poets. On the other hand, the importance given to life that worldly fame and glory provide, compared to the medieval ubi sunt?, is also a trait of anthropocentrism that heralds the Renaissance.

The communicative force that Jorge Manrique achieves in the Coplas is very powerful. In his verses he introduces themes that have already been dealt with previously: death and the ephemeral, but he does so by endowing each stanza with enormous beauty, achieving a poem of extraordinary uniformity and unity.

Alan Deyermond points out that the Coplas also constitute a reflection of society from a critical perspective towards the frivolities and vanities of his time. They talk about life at court, the manly world and the decline of chivalry, women and the development of salons, various festivals and Castile of the century XV.

Jorge Manrique in Spanish literature

The work of Jorge Manrique has marked many later authors who have shown great interest and admiration for his poetry, especially for the Coplas por la muerte de su padre. His verses have been widely recreated and have survived through time as a source of inspiration.

Just was my downfall

Some of his compositions were sung and highly celebrated by posterity. The song Justa fue mi perdición was widely disseminated with music by Juan de Urrede in the 16th and 17th centuries and is one of the most famous courtly love songs of the Golden Age. Proof of this are the numerous documentary sources in which it has survived: fourteen manuscripts that mention it and more than forty different printed editions in which it is copied or glossed.

The text of this song is preserved in the Cancionero general, in the musical songbooks Cancionero de Palacio and Cancionero de Segovia and in others handwritten and printed non-musical songbooks. It also appears glossed in handwritten and printed songbooks, both collective and individual, and quoted or alluded to in works in prose and verse. It is glossed by authors such as Juan Boscán, Juan Fernández de Heredia, Andrade Caminha, Luis Vaz de Camoens, Joaquín Romero de Cepeda, Gregorio Silvestre or Francisco de Borja. Lope de Vega mentions her in La Dorotea and in the plays La prueba de los ingenios and Perfiar until death.

The extensive dissemination of Justa was my downfall during this time is not directly related, however, to the personal fame of Jorge Manrique, since the documents in which it is preserved barely mention his name.

Musical versions of the Coplas

Starting in the 1540s, renowned musicians from the 16th and 17th centuries composed musical versions of Jorge Manrique's Coplas por la muerte de su padre. Six versions composed by Alonso Mudarra, Luis Venegas de Henestrosa, Juan Navarro de Sevilla, Pere Alberc i Vila, Melchor Robledo and Francisco Guerrero are currently preserved. In addition, there are testimonies of two other versions by Philippe Rogier and Gabriel Díaz Bessón, now lost. Some of these musical versions of the Coplas must have been well known to the public at the time, since they were sung in the corrales de comedias and at Corpus Christi festivities.

Jorge Manrique in the Golden Age

Manrique's commentators were very numerous in the Golden Age and surely no cult poem of the XV century inspired so many composers of this period as did the Coplas. Lope de Vega went so far as to say of this poem in the prologue to El Isidro that it "deserved to be written in letters of gold".

The Manrique work is present in our classical theater, sung or glossed. Lope mentions her in La Dorotea, and in two plays: La prueba de los ingenios and Perfiar until death. Also in La devoción del Rosario, a comedy dated between 1604 and 1615.

The generations of '27 and '98 and Jorge Manrique

The noventayochistas Miguel de Unamuno, Ramiro de Maeztu, Azorín and Antonio Machado, each approached Jorge Manrique in their own peculiar way, but all from a great affection for the Castilian poet.

In his Life of Don Quixote and Sancho, Unamuno rescues six verses from the Coplas for the episode of the death of Don Quixote. Also in his Cancionero recalls Jorge Manrique as a character and creator in the poem Passing through Carrión de los Condes.

Maeztu appreciates and comments affectionately on Manrique's verses in his admission speech to the Royal Spanish Academy, defending and praising the Coplas. Throughout his speech, Maeztu talks about the subject of the brevity of life and its presence in Castilian lyric poetry. He presents Manrique as a fully influential man and an example of literary sobriety and simplicity.

Azorín tries to portray the spirit of Manrique: «Jorge Manrique... What was Jorge Manrique like? Jorge Manrique is an ethereal, subtle, fragile, brittle thing. Jorge Manrique is a slight chill that overwhelms us for a moment and makes us think. Jorge Manrique is a burst that takes our spirit there, towards an ideal distance.» He introduces us to a "revived" Manrique who is still by our side today.

Jorge Manrique is Antonio Machado's favorite poet: "Among my poets / Manrique has an altar", he says in his poem Glosa. Machado was an annotator of Manrique and in several of his poems Manrique's inspiration is clearly appreciated. He deeply appreciates the medieval poet's simple creation around the everyday and his admiration reaches the point of giving his last and mysterious love the name of Manrique's wife, Guiomar.

For the poets of the Generation of '27, Jorge Manrique was also the most esteemed medieval poet. Luis Cernuda describes him as a “metaphysical poet.” Jorge Guillén titled the second book of his work Clamor with a verse by Manrique, Que van adar en la mar . Pedro Salinas dedicates a fundamental study to him, the essay Jorge Manrique, or, tradition and originality where he describes the figure of the poet thus:

It is certainly not the conceptual content of the Copiesinvented and formulated by many. Nor is the work of his invention the metric form of the Copies. His personality must therefore be found in his treatment of that past, in his attitude towards tradition. That's what, a mi ver, define the poetic figure of Jorge Manrique.Pedro Salinas

The Manrique triangle

For more than twenty years the Cuenca towns of Castillo de Garcimuñoz, where he was mortally wounded, Santa María del Campo Rus, where he died, and Uclés, where he was buried, commemorate the Manrique days on the last Saturday of April, which they rotate from one town to the next, in which the highlight of the acts is always a speech about the figure of Jorge Manrique.

Contenido relacionado

John Vincent Gomez

Krzysztof Zanussi

Maus