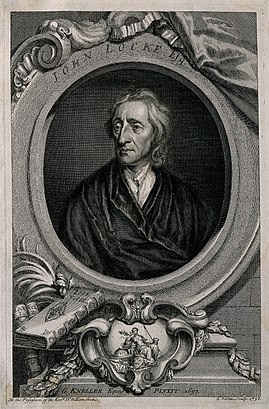

John Locke

John Locke (Wrington, Somerset, August 29, 1632-Essex, October 28, 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, considered one of the most influential thinkers of English empiricism and known as the "Father of Classical Liberalism". He was one of the first British empiricists. Influenced by the ideas of Francis Bacon, he made an important contribution to the theory of the social contract. His work greatly affected the development of epistemology and political philosophy. His writings influenced Voltaire and Rousseau, French Enlightenment thinkers, as well as American revolutionaries. His contributions to classical republicanism and liberal theory are reflected in the United States Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights of 1689.

Locke's theory of mind is frequently cited as the origin of modern conceptions of identity and self, which figure prominently in the works of later philosophers such as Hume, Rousseau, and Kant. Locke was the first to define the self as a continuity of consciousness. He postulated that, at birth, the mind was a blank slate or blank tabula. Contrary to Cartesian philosophy —based on pre-existing concepts— he maintained that we are born without innate ideas, and that, instead, knowledge is only determined by experience derived from sensory perception.

He studied thanks to a scholarship to the prestigious Christ of Oxford, which, as usual then, reduced his studies to scholastic philosophy and ignored Cartesian philosophy and the advances of the new science or mathematics. Disappointed, he redirected his career to chemical experiments (he was a collaborator of Robert Boyle) and the study of medicine. Professor of classical Greek at Oxford, it was not until he was thirty-four years old that he read Descartes' philosophy, which awakened in him "a taste for philosophical studies" and built a decisive influence on him (he saw it as a true alternative to scholasticism).. He was also influenced by Pierre Gassendi (a philosopher who was critical of Descartes and a follower of Epicureanism) and, in political philosophy, by the British Hobbes and Shaftesbury. He lived in London, for four years in France and was briefly in exile in the Netherlands. When he returned to London, after the Glorious Revolution, he became an adviser to the whigs (representatives of the liberal party).

Biography

He was born on August 29, 1632, in a small thatched cottage near the church in Wrington, Somerset, about eight miles from Bristol. He was baptized the same day. Locke's father, also called John, was a country solicitor and clerk at the Justices of the Peace in Chew Magna, who had served as a cavalry captain in the Parliamentarian forces during the early part of the English Civil War. His mother's name was Agnes Keene. Both parents were Puritans. Shortly after Locke's birth, the family moved to the market area of Pensford, about four miles south of Bristol, where he grew up in a rural Tudor house in Belluton.

In 1647, Locke was sent to the prestigious Westminster School in London, under the patronage of Alexander Popham, a member of Parliament and his father's former boss. After completing his studies there, he was admitted to Christ Church (Oxford). The dean of the college at the time was John Owen, vice-chancellor of the university. Although an able student, Locke chafed at the undergraduate curriculum of the time. He found works by modern philosophers, such as René Descartes, more interesting than the classical material taught at the university. Through his friend Richard Lower, whom he knew from Westminster School, he was introduced to medicine and experimental philosophy as applied at other universities and at the Royal Society, of which he eventually became a member.

He was awarded his bachelor's degree in 1656 and his master's degree in 1658. He obtained a medical degree in 1674, because he studied medicine deeply while at Oxford and worked with several notable scientists and thinkers such as Robert Boyle, Thomas Willis, Robert Hooke and Richard Lower. In 1666, he met Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, who had come to Oxford seeking medical treatment for a liver infection. Cooper was impressed with Locke and convinced him to become part of his entourage.

Locke had tried to find a stable career and in 1667 moved to Lord Ashley's home at Exeter House, London, to serve as his personal physician. In London, he resumed his medical studies under Thomas Sydenham. Sydenham had a major effect on Locke's natural philosophical thought—an effect that would become apparent in Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

Locke's medical knowledge was put to the test when Shaftesbury's liver infection became life-threatening. He coordinated a council of several doctors and was probably instrumental in convincing Shaftesbury to undergo an operation (although it was also life-threatening) to remove a cyst. Shaftesbury survived and recovered, thanking Locke for saving his life.

In 1671 a meeting took place at Shaftesbury House, which was described in the "Epistle to the Reader" of the Essay Concerning Understanding human, which inspired the Essay.[citation needed] Two extant drafts from this period still survive. Also during this time, Locke served as secretary to the Board of Trade and Plantations and as titular secretary to the Lords of Carolina, where he used to shape his ideas on international trade and economics.

Shaftesbury, as one of the founders of the Whig movement, exerted a great influence on Locke's political ideas. He became involved in politics when Shaftesbury became Lord Chancellor in 1672. Following Shaftesbury's loss of favor in 1675, Locke spent some time traveling throughout France as Caleb Banks' tutor and physician's assistant. He returned to England in 1679., when Shaftesbury's political fortunes underwent a brief positive turnaround. Around this time, most likely in Shaftesbury's heyday, Locke composed most of the Two Treatises on Civil Government. Although Locke was thought to have written the Tractates to defend the Glorious Revolution of 1688, recent scholarship has shown that the work was written before that date. The work is now regarded as a more general argument against absolute monarchy (particularly expounded by Robert Filmer and Thomas Hobbes) and to achieve individual consent as the basis of political legitimacy. Although he associated with influential whigs, his ideas about natural rights and government are now considered to be quite revolutionary for that period of English history.

He fled to the Netherlands in 1683, as he was strongly suspected of having participated in the Rye House Plot, although there is little evidence to suggest that he was directly involved in the plot. Philosopher and novelist Rebecca Newberger Goldstein argues that during his five years in the Netherlands, Locke chose his friends "among the same freethinking members of dissident Protestant groups as the small circle of confidantes loyal to Spinoza. [Baruch Spinoza had died in 1677.] Locke most likely met with several men in Amsterdam who discussed the ideas of renegade Jews who... insisted on identifying themselves through their religion as the only reason." Although she said that "Locke's strong empiricist tendencies" would have "inclined him to read such a great metaphysical work as Spinoza's Ethics, which among other things was a profound exposition of Spinoza's ideas, and very especially as a thoughtful argument for the good of the rationalists on political and religious tolerance and the need for the separation of Church and State».

In the Netherlands, he had time to return to writing and invested heavily in returning to work on the Essay and composing the Letter on Tolerance. He did not return home until after the Glorious Revolution, and he accompanied the wife of William of Orange on her return to England in 1689. Most of Locke's publications were written after his return from exile—his Essay on the aforementioned human understanding, the Two Treatises on Civil Government and the Charter on Toleration are printed in rapid succession.

Mrs. Masham, a close friend of Locke's, invited him to the Mashams' country house in Essex. Although his stay there was marked by variable health from his asthma attacks, he became an intellectual hero of the whigs. During this period, he discussed topics with such figures as John Dryden and Isaac Newton.

He died on 28 October 1704, and was buried in the churchyard in the town of High Laver, east of Harlow, Essex, where he had lived in the house of sir Francis Masham. since 1691. Locke never married or had children.

Events that occurred during Locke's lifetime include the English Restoration, the Great Plague, and the Great Fire of London. He did not witness the Act of Union of 1707, although the thrones of England and Scotland were held in personal union throughout his life. Constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy had been in place since his childhood during Locke's time.

Basics of John Locke's Thought

His epistemology (theory of knowledge) does not believe in the existence of innateness and determinism, considering knowledge of sensory origin, so he rejects the absolute idea in favor of mathematical probabilistic. For Locke, knowledge only reaches the relationships between facts, the how, not the why. On the other hand, he believes he perceives a global harmony, supported by self-evident beliefs and assumptions, so his thoughts also contain elements of rationalism and mechanism. He believes in a creator God close to the conception of the great watchmaker, basing his argument on our own existence and on the impossibility that nothing can produce being. That is, a God as described by the rationalist thinker, René Descartes, in the Discourse on Method, in the third part of it. Of the divine essence only accidents can be known and its designs can only be noticed through natural laws.

It treats religion as a private and individual matter, which affects only man's relationship with God, not human relationships. By virtue of this privatization, man frees himself from his dependence on ecclesiastical impositions and withdraws confessional legitimacy from political authority, since he considers that there is no biblical basis for a Christian state.

Considers the natural law a divine decree that imposes global harmony through a mental disposition (reverence, fear of God, natural filial affection, love of neighbor), materialized in prohibited actions (stealing, killing and ultimately any violation freedom of others), which oblige in favor of coexistence.

Epistemology

John Locke finished writing it in 1666, but it was not published until 1690, the year in which it came to light under the original English title of An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. In this treatise, Locke laid out the foundations of human knowledge and warned of his intention to carry out a "morally useful work". Conceived at the time of great scientific discoveries (especially palpable in the works of Christiaan Huygens and Isaac Newton), Locke thought that philosophy had to participate in these important advances, eliminating, for example, all useless inventions and concepts accumulated over the years. the previous centuries. According to him, the analogies and relationships between the contents of knowledge are the elements that allow the development of critical instruments capable of eliminating erroneous knowledge. Due to his characteristic analytical empiricism, he opposed Cartesian purely mechanistic and systematic conceptions and, despite being questioned by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, his influence on the philosophers of the Enlightenment was considerable.

- In the first book of EssayLocke insisted on the need to dispense with considerations a priori and, in opposition to Rene Descartes, he said that there is no innate knowledge and that only the experience should be taken into account. Locke criticized the Descartes version of the dream argument by counteracting that people cannot have physical pain in dreams as they do in life.

- In the second book, he proposed that feeling (or ideas of sensation, the "impressions made in our senses by outer objects") and reflection (or ideas of reflection, "reflection of the spirit over its own operations based on ideas of sensation"), are based on the experience and simple ideas created by the immediate perception derived from the excitations that come from objects.

Individuals have the ability to represent objects, as well as a free will to determine them. The reason presents simple ideas in three groups: conjunction, abstraction and combination.

The mind, moreover, has the ability to associate and combine these simple ideas, thus producing the complex ideas that can be: substance (individual things that exist), so (the ones that do not exist in themselves but in a substance) and relationships (that describe associations of ideas).

- In the third book he was interested in the relations between language and thought, in the intersubjective formation of knowledge. The words refer to general ideas that are evidenced by successive subtractions of their circumstantial peculiarities. It distinguished between the nominal essences (which are complex, and established to serve the selection and classification of ideas) and the real essences (for use of metaphysics, inaccessible to reason, which cannot have access to its knowledge).

- In the fourth book he tried to find out what is established from the agreement or disagreement between two ideas, either by intuition, by rational demonstration or by sensitive knowledge. Practical confrontation allows to clear the doubt. They are not connections between ideas born of sensitive qualities that we perceive. In fact, human knowledge is based on the definitions it gives to things called "real". Human knowledge is therefore limited. Only the knowledge provided by the senses can indicate what actually exists in the objects of the world. Truth is only a matter of words, while reality interests the senses. In the absence of something better, to alleviate the limitation of the cognitive possibilities of reality you can try to use in a discourse the notion of "probable" things. For Locke, God is the result of inference and the teachings resulting from faith must agree with reason. Atheism and skepticism are therefore very present in John Locke, as in most English empirists.

In summary, the main idea underlying the Essay is that only sensation allows the understanding of reality and that truth belongs only to discourse.

Blank Slate

Locke defines the self as "that thing of conscious thought (whatever the substance, whether spiritual, material, simple or compound, it does not matter) which is sentient or conscious of pleasure and pain, capable of happiness or misery, and so he cares for himself, to the extent that this awareness spreads». However, he is not ignorant of "substance", writing that "the body also goes to make the man". John Locke viewed personal identity as a matter of psychological continuity based on consciousness (i.e. memory), not in the substance of soul or body. Book II, chapter XXVII, titled "On Identity and Diversity", of his Essay Concerning Human Understanding is one of the earliest modern conceptualizations of consciousness. as the repeated self-identification of oneself. Through this identification, moral responsibility could be attributed to the subject, and punishment and guilt could be justified.

In his Essay, Locke explains the gradual development of this conscious mind by arguing against the Augustinian view of man as originally sinful, and against the Cartesian position, which holds that man innately knows the basic logical propositions. Locke posits an "empty" mind, a blank tabula, a blank table or slate. Learning occurs through experience where subjects put their five senses to the test. Sensations and reflections are the two sources of all our ideas.

Simple and complex ideas

Locke assumes that there is an object of thought, and this object is called an idea. According to Locke, simple ideas are indivisible and complete, but they are not always clear; they are unmixed, homogeneous and unanalyzable: one cannot therefore define or explain them. Neither can they be communicated or known without personal experience. These ideas are only the materials of our thought. He distinguishes two types of simple ideas: simple and complex ideas.

- Simple ideas: He believes that they are those who come from the experience, and that the understanding receives in a passive way. Depending on its origin, Locke asserts that they can be classified into three categories: sensation, reflection or both.

- For example: color, heat, cold, taste, etc.

- Complex ideas: are ideas made in mind from simple ideas. Locke tells us that there are four categories of composite ideas: substance, modes, relationships and universal.

- That is, the idea of space (mode), causality (relationship) or the idea of man (universal).

According to Locke, understanding by composition groups a series of simple ideas into a whole that he calls substance. But the substance remains unperceived. Locke finally affirms that the substance is something necessary in which the qualities go but unknowable. Substances are independent existences. Beings that count as substances include God, angels, humans, animals, plants, and a variety of built things. The modes are dependent existences. The modes give us the ideas of mathematics, morality, religion and politics and human conventions in general.

Primary and secondary qualities

The origin of indirect realism arises with John Locke in rejecting the claim that physical objects are the direct objects of perception. Locke classified sensory perfections into two qualities as follows:

- The primary qualities They are qualities that are "explanably basic", that is, they can be referred as the explanation of other qualities or phenomena without requiring their own explanation, and they are different because our sensory experience of them resembles them in reality. (For example, one perceives an object as spherical precisely by the way in which the atoms of the sphere are arranged.) Primary qualities cannot be eliminated either by thought or by physical action, and include mass, movement and, controversially, solidity.

- The secondary qualities are qualities that the experience of one does not seem directly; for example, when one sees an object as red, the sensation of seeing redness does not occur by some quality of redness in the object, but by the disposition of the atoms on the surface of the object that reflects and absorbs the light in a particular way. Secondary qualities include color, smell and taste.

Knowledge

Locke has thus established, for this analysis of ideas, that all our knowledge has about our ideas, about the relationships they have between them and about their modifications. Knowledge therefore consists of the perception we have of the convenience or non-convenience that our ideas have among themselves. Knowing is comparing ideas, discovering their relationships, and judging.

He distinguishes four types of conveniences and non-conveniences that correspond more or less to areas of human knowledge:

- identity or diversity (logic)

- relationship (mathmatic)

- necessary coexistence (physical)

- actual existence (metaphysics)

He also distinguishes four types of knowledge: certainty derives from the first two; from the third opinion and probability; from the fourth faith.

Political Thought

According to his ideas, the State's main mission is to protect three natural rights: life, liberty and private property of everything that a man has worked and can use, since property has a limit; To these three rights a fourth is added: the right to defend these rights, as well as any other individual freedom of citizens, which the citizen cedes to the State by means of a written consent or constitution. He also holds that the government should consist of a king and a parliament. Parliament is where popular sovereignty is expressed and where laws are made that must be followed by both the king and the people. Anticipating Montesquieu, who was influenced by Locke, he describes the separation of legislative and executive power. The authority of the State is sustained in the principles of popular sovereignty and legality. Power is not absolute but must respect human rights.

The State confers decision-making functions in controversies between individuals, in the context of plurality and tolerance, since there are diversity of opinions and interests among men, the result of the different individual ways of seeking happiness, so disagreement and conflicts are inevitable.

Postulates that men live in the state of nature in a situation of peace and subject to natural laws that arise from reason (the right to exercise justice into their own hands and the limitation of private property through elements in their most perishable). Men leave it after having generated a situation of injustice, both in punishment and in compensation for the crime committed, which leads to an infinite cycle of subsequent injustices. And that this process of creating civil and/or political society occurs through a social contract designed to protect private property and the lives of individuals.

For pedagogical purposes this is divided into two parts:

- Union contract: Unit of the parties to form a society → Creation of civil society.

- Subjecting contract: Men's ligament to certain political construction → Creation of political society.

This political society has the duty to guarantee impartial justice so as not to return to a situation of conflict again. If it does not guarantee private property or life, the contract of subjection is broken and another political organization is formed.

Work-Ownership Theory

The theory of ownership-work or appropriation-work is a theory of natural law that argues that ownership originally comes from the application of work on natural resources (this should not be confused with the theory of value-work).

In his Two Treaties on Civil Government, the philosopher John Locke asks on the basis of what right an individual can claim as his own a part of the world, when, according to the Bible, God gave the world to all humanity in common. He replied that people own themselves and therefore own their own work. When a person works, that effort enters the object. Thus, the object becomes the property of the person.

Locke argued in support of individual property rights that are "natural rights." After the argument of the fruits of the work are "your" because he had worked for them, in addition, the worker must also have a natural property right over the resource itself, because, as Locke believes, exclusive property is the first need for production. Jean-Jacques Rousseau later criticized this second step in the Discourse on Inequality, where effectively argues that the argument of natural law will not extend to the resources that one does not believe. Both philosophers argue that the relationship between work and property refers only to the property that it did not own before this type of work was carried out.

The land in its original state would be considered not-appropriate by anyone, but if an individual applies his work to land through agriculture, for example, he becomes his property. The mere fact of placing a fence around the earth instead of using the earth is not attached as property according to most theorists of the natural law. For example, economist Murray Rothbard said:

If Columbus rises to a new continent, is it legitimate to proclaim the whole new continent as his own, or even the sector "as far as the eye can see"? Obviously, This would not be the case in the free society that we are postulating. Columbus or Crusoe would have to use the land, "cultivate it" in some way, before he could assert ownership over it... If there are more land that can be used by a limited job offer, then the unused land should simply remain unappropriate until a first user arrives at the scene. Any attempt to request a new resource that someone does not use would have to be considered an invasion of the property right of anyone who becomes the first user.Man, economy and state

The theory of property-working not only applies to land itself, but to the application of work on nature. For example, the iusnaturalist Lysander Spooner says that an apple taken from a tree without owner becomes the property of the person who harvests it, as he has worked to acquire it. He says "the only way, in which 'the richness of nature' can be made useful to mankind, is by its taking of possession individually, and making it privately owned. "

However, some, like Benjamin Tucker, have not seen this property creation in all things. Tucker argued that "in the case of land, or of any other material where the offer is so limited that it cannot be held in unlimited quantities," these should only be considered property while the individual is in the act of using or occupying these things.Religious tolerance

Locke, writing his Letters on Tolerance (1689-1692) after the European Wars of Religion, formulated a classic rationale for religious toleration. Three arguments are central:

- Earthly judges, the State in particular and human beings in general, cannot reliably assess the truthful assertions of religious views in competition;

- Even if they could, to enforce a single "true religion" would not have the desired effect, because violence cannot force belief;

- Coacting religious uniformity would lead to more social disorder than allowing diversity.

Although Locke was an advocate of toleration, he urged the authorities not to tolerate atheism, because he believed that the denial of the existence of God would undermine social order and lead to chaos. As for Catholics, Locke believes that they cannot be trusted with genuine loyalty to the law, since "they owe blind obedience to an infallible pope, who has the keys of their consciences strapped to his belt, and can on occasion dispense with all their oaths, promises and obligations they have with their prince".

Intolerance has, for Locke, its origin in the confusion between Church and State: A religious State does not derive its legitimacy from the people, but from a divine right. Against such a theocratic state, the individual has the right to rebel.

In his position on religious toleration, Locke was influenced by Baptist theologians such as John Smyth and Thomas Helwys, who had published tracts calling for freedom of conscience in the early 17th century. Baptist theologian Roger Williams founded the Rhode Island colony in 1636, where he combined a democratic constitution with unlimited religious freedom. His treatise The Bloody Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience (1644), which was widely read in the mother country, was an impassioned plea for absolute religious freedom and total separation from the Church and the state. Freedom of conscience had been high on the theological, philosophical, and political agenda, since Martin Luther refused to recant his beliefs before the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire in Worms in 1521, unless the Bible proved it false..

Pedagogy

Education and#34;knightly#34;

All his pedagogical thinking is concerned with dictating certain rules to shape the personality that he wants to implant in the student, and obviously in this case, it is about making the boys train until they become "gentlemen& #3. 4; in the sense of "gentlemen".

With all this, the education that he proposes takes a strictly disciplinary sense and thus, the bases of his didactics are exercise and, obviously, discipline; Discipline is the way to develop in the human mind the habit of reflecting and reasoning, and thus determine the spirit of the person being educated, so that the customs also characterize their personality in the future, as explained in the previous paragraph.

The purpose of disciplinary education is to be very clear about the personality you want to reach, which is explained in the following section; It also means "forming the person capable of thinking and willing freely, tending to improve it so that it is useful for himself and for society".

For him, Pedagogy is a painful and tiring procedure with which bad habits are eliminated and the best dispositions are strengthened and developed, which he understood as developing a "gentle" or "knightly" in the sense of gentlemen, and not so much as intellectual or scientific development. Education for him consisted of training man for life and for the needs of society, which implies giving him a job, he considered it good to give the poor jobs of less dignity, and to the rich give them jobs of greater dignity, this through education.

The method of their instruction is intuitive, which refers to the fact that knowledge derives from the senses, so the boys must discover knowledge, guiding themselves with the help of experience; they learn by touching, seeing and admiring everything that surrounds them. In addition, "the development of the child must be followed step by step".

Characteristics of a gentleman

Through his discipline, John Locke wants to form a modern, healthy and robust gentleman who meets the following characteristics:

- He can do his job well.

- He is in a position to hold a position of social responsibility.

- It makes sense of honor, so it is respected by others.

- He has learned more from the trips he makes and from direct experience with things than by books.

- He has formed a personal criterion with which he is able to judge things.

- It has a solid and useful knowledge for life.

- He possesses the virtue of knowing how to master his feelings and subject them to reason, before acting according to them.

Intellectual education

The first thing that had to be considered to make this training possible is that what was really useful for education had to be chosen; for him, "useful for the intellectual formation of man is everything that accustoms him to examine the arguments for or against a given opinion, so that he can assume a personal attitude towards it."

Educating within the intellectual field means teaching to reason.

So, starting from this idea, I said that the brevity of life does not allow one to afford the luxury of wasting time in a study program that has only aesthetic value, and not practical, since humanistic and formal instruction, where The teaching is mainly focused on the students learning Greek and Latin, it will only serve those who want to train as professional 'wise', but their mother tongue, the child will learn it because they will recognize that it is useful and it is not necessary that someone has to instill it in him and make him learn it.

What is really useful for their training and that really has a formative value for intelligence, is the teaching of mathematics and logic, because these disciplines enhance the intellectual faculties and enable them to learn better.

Among the important disciplines for him, geography stands out, as it broadens the vision of the gentleman; history, because it stimulates the imagination and also teaches us how the present is determined by the past.

Physical Education

The purpose of physical education is to follow the evolution of the child and make him follow, too, a gradual discipline. Likewise, it not only has a hygienic or aesthetic purpose (as it was for humanists), but rather helps to form character and good morality.

It states that the body must be subjected to the rigid rules of hardening, just as the Spartans did, so that in the future man can withstand the elements and his physical resistance will help him withstand illnesses or suffering.

More than practicing gymnastics or sports, he recommends swimming and horse riding, since they are useful activities for any circumstance.

For this reason, it was important to study anatomy, because that way you are more aware of the physical capacities and functions that we have.

Moral education

As for moral education, much more discipline is needed.

The purpose of this education is to achieve virtue, which, for him, consists in the fact that one must learn to always and only love what is good before reason and therefore, it is good not to accustom man, from childhood, to give him everything he wants.

To better explain this idea, Locke tells us that «He who in his youth has not been accustomed by force to subordinate his own will to the reason of others, will hardly accept submitting to his own reason when he is of an age to make use of it. of her".

He also considered that instincts should be controlled with a discipline that would prepare man, so that he would only do those things that would not offend the dignity or excellence of a reasonable creature.

For this type of education, he recommended reading Seneca and Marcus Aurelius.

Not least, but not so important, it is important to him that the Fine Arts be known, and especially, that the gentleman may like painting, but not poetry.

Regarding the lower classes

Evidently, "his greatest concern was with the upper classes and he had very little faith in the ability of the common man."

The considerations he has regarding the education of the lower classes are that the children of the poor should be separated from their parents to educate them in schools where they were taught a trade, from the age of three to fourteen. The trades that will be taught will be simple.

He also emphasizes here the importance of discipline, since thanks to it, lower-class children will be prevented from becoming delinquents.

Instilling in them virtues is also important, mainly saving and love of work.

Their moral education will be formed according to the precepts of the Bible.

As can be seen, "Locke was not in favor of academic instruction for the poor, instead recommending apprenticeship, which he said began early in the morning and finished late at night."

Role of the teacher

The teacher's ability resided in obtaining and maintaining the attention of the student, to incline him to follow the rules and he had to also respect his natural development, relying on self-esteem and the sense of honor that the boy was supposed to already have developed.

Epitaph

Original in Latin:

SISTE, VIATOR, Hic juxta situs est Joannes Locke. If qualis fuerit rogas, mediocrite sua contentum se vixesse respondert. Literis innutritus eousque profecit, ut veritati unice litaret. Hoc ex scriptis illius disce; quæ, quod de eo reliquum est majori fide tibe exhibitionebunt, quam epitaphii suspecta commends. Virtutes si quas habuit, minores sane quam sibi laudi, tibi in exemplum proposeet. I saw a sepeliantur. Morum exemplum if quæras, in gospel habes; vitiorum utinam nusquam: mortalitatis, certe, quod prosit, hic et ubique.Natum Anno Dom. 1632 Aug. 29th

Mortuum Anno Dom. 1704 Oct. 28th

Memorat hac tabula - brevi et ipse interitura.

Translated from the Latin:

Stop, traveler. This is John Locke. If you wonder what kind of man he was, he would tell you that someone happy with his medianship. Someone who, although not so far in the sciences, only sought the truth. You'll know this in their writings. From what he leaves, they will inform you more faithfully than the suspicious praises of the epitaphs. Virtues, if he had them, not so much to praise him or to give him an example. Vicios, some with whom he was buried. If you look for an example to follow, in the Gospels you find it; if one of vice, I hope nowhere; if one of the mortality is profitable, here and everywhere.Who was born on August 29 of the year of Our Lord of 1632,

and who died on October 28 of the year of Our Lord of 1704,

This epitaph, which will also perish soon, is a record.

Works

- Tests on the civil government (1660-1662)

- Tests on the law of nature (1664)

- Test on tolerance (1667)

- Compendium of the Test on Human Understanding (1688) published in the Bibliothèque universelle edited by Jean Leclerc

- Letter on Tolerance (1689)

- Civil Government Treaties (1689). Reissued in 1690, 1698 and 1713. Each reissue includes changes and variations on the previous one. Although Locke himself reported in a letter that the latest version (published posthumously by his secretary in 1713) is the one that wanted to "pass posterity", currently translations of the first and third version are still being edited. There are important changes, especially in chapter V on ownership. Cf. Peter Laslett, "Introduction". In Two Treatises on Government (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

- Testing on human understanding (1690)

- Second Letter on Tolerance (1690)

- Some considerations on the impact of interest reduction and the rise in the value of money (Rewritten in 1668 and published in 1691). Original Title: Some Considerations of the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest, and Raising the Value of Money.

- Third Charter on Tolerance (1692), in which he defends his own arguments of Joan Proast's attacks.

- Some thoughts about education (1693)

- Reasonability of Christianity (1695)

- A vindication of the rationability of Christianity (1695)

- More considerations about raising the value of money (1695). Original title: Further Considerations Concerning Raising the Value of Money.

Unpublished or posthumous manuscripts

- 1660. First Treaty of Government (o) the English Tract)

- c.1662. Second Treaty of Government (o) the Latin Tract)

- 1664. Questions Concerning the Law of Nature (final Latin text, translated into Robert Horwitz English) et al.eds, John Locke, Questions Concerning the Law of NatureIthaca: Cornell University Press, 1990.

- 1667. Essay Concerning Toleration

- 1669. The Fundamental Constitutions for the Government of Carolina. (There is a controversy about whether this manuscript is an original work of Locke, or that in the writing of it simply exercises its role as secretary of the Lords Proprietors of Carolina. See J. R. Milton, John Locke and the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina. Lockeed. J. Dunn and I. M. Harris, Lyme, USA: Edward Elgar Publ., 1997, 463-485; W. Glausser, «Three Approaches to Locke and the Slave Trade. » Journal of the History of Ideas 51, n.o 2, Jun. 1990: 199-216; J. Tully, “Rediscovering America: The Two Treatises and Aboriginal Rights,” at Locke’s Philosophy: Content and Context, ed. G. A. J. Rogers, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994, 165-196; K. H. D. Haley, The first Earl of Shaftesbury, Oxford: Claredon Press, 1968; J. Farr «So Vile and Miserable an Estate»: The Problem of Slavery in Locke's Political Thought. » Political Theory 14, no. 2, May 1986: 263-289; S. Drescher, "On James Farr's 'So Vile and Miserable an Estate'. » Political Theory 16, No. 3, Ago. 1988: 502-503; J. Farr, ""Slaves Bought with Money": A Reply to Drescher. » Political Theory 17, No. 3, Aug. 1989: 471-474.)

- 1676. Obligation of Criminal Laws. (Original title: Obligation of Penal Laws).

- 1681-2. A defence of nonconformity in response to the sermon of Edward Stillingfleet. (The text was probably written by John Locke. See J. Marshall, John Locke: Resistance, Religion, and Responsibility, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, 96-110. However, Cranston argues that James Tyrrel could also participate in the drafting of the pamphlet. Cf. Cranston, M., John Locke: A Biography, London: Longmans, 1968, p. 194.

- 1686-7. General ethics. (Original title: Of Ethick in General).

- 1690. Alliance and Revolution. (Original title: On Allegiance and the Revolution).

- 1697. Proceedings on the Law of the Poor. (Original title: Essay on the Poor Law).

- 1706. The conduct of understanding

- 1707. Paraphrases & Notes in the Epistles of St. Paul

Editions

- The Works of John Locke, by L. J. Churchill, 3 volumes, London 1714

- The Works of John Locke, 9 volumes, London 1853

A source of information on the bibliography of and about John Locke is John Locke Resources, a website developed by the University of Pennsylvania and directed by Roland Hall, where the repository is extremely complete and updated monthly. Includes primary and secondary sources in all languages.

The following are editions of the works of John Locke in Spanish:

- LOCKE, J., Complete work. Agustín Izquierdo Edition. Library of Great Thinkers. Madrid: Editorial Gredos, 2013. ISBN 978-84-249-0455-5.

- LOCKE, J., Test on tolerance and other writings on ethics and civil obedience. Selection of texts, translation, introduction and notes by Blanca Rodríguez López and Diego A. Fernández Peychaux. Madrid: New Library, 2011. ISBN 978-84-9940-231-4.

- LOCKE, J., The law of nature, translation Carlos Mellizo, Classics of Thought, Madrid, Tecnos, D. L., 2007. ISBN 978-84-309-4538-2.

- LOCKE, J., Second Civil Government Treaty: an essay on the true origin, scope and end of the civil government, translation of Carlos Mellizo, Classics of thought, Madrid, Tecnos, 2006. ISBN 84-309-4435-4.

- LOCKE, J., Test and Letter on Tolerance, translation Carlos Mellizo, Madrid, Alianza Editorial, 2005. ISBN 84-206-3983-4.

- LOCKE, J., Youth Political Writers (II): The Latin Trial of 1662. Translation C. Love. Buenos Aires: Devs Mortalis, Nro 2, 2003.

- LOCKE, J., Second Civil Government Test. An essay on the true origin, scope and purpose of the civil government. Translation Cristina Piña. Buenos Aires: La página-Losada, 2003. ISBN 950-03-9241-0.

- LOCKE, J., Youth Political Writings (I): The English Trial of 1660. Translation C. Love. Buenos Aires: Devs Mortalis, Nro 1, 2002.

- LOCKE, J., Second Government Treaty: an essay on the true origin, scope and end of the civil governmented. by Pablo López Álvarez, Clásicos del Pensamiento 7, Madrid, Biblioteca Nueva, 1999. ISBN 84-7030-625-1. (Reproduction of the 3rd edition)

- LOCKE, J., Monetary Writings. Introduction of Martin Victoriano, translation of María Olaechea, Madrid, Pirámide, 1999. ISBN 84-368-1295-6.

- LOCKE, J., Written on Tolerance. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales, 1999. ISBN 84-259-1089-7.

- LOCKE, J., Compendium of the Human Understanding Test. Translation Rogelio Rovira and Juan José García Norro, Madrid, Tecnos, 1998. ISBN 84-206-7291-2.

- LOCKE, J., Tests on natural law. Critical edition by Isabel Ruiz-Gallard. Madrid: Universidad Complutense, Facultad de Derecho, Servicio de Publicaciones: Centro de Estudios Superiores y Jurídicos Ramón Carande, D.L. 1998. ISBN 84-89764-96-4.

- LOCKE, J., Lessons on the Natural Law: Funeral Discourse of the Census. Introduction by Manuel Salguero; Latin translation and notes by Manuel Salguero and Andrés Espinosa. Granada: Comares, 1998. ISBN 84-8151-753-4.

- LOCKE, J., Review of the Opinion of Father Malebranche that we see all things in God. Translation Juan José García Norro. Excerpt Philosophica 8, Madrid, Faculty of Philosophy of the Complutense University, 1994. ISBN 84-88463-04-9.

- LOCKE, J., Human Understanding Test, Translation Edmundo O’Gorman, Mexico [etc.], Economic Culture Fund, 1994. ISBN 958-38-0006-6.

- LOCKE, J., The Conduct of Understanding and Other Posthumous Trials. Introduction, translation and notes by Angel. M. Lorenzo. Barcelona: Anthropos [etc.], 1992. ISBN 84-7658-296-X.

- LOCKE, J., Two Civil Government Testsed. Joaquín Abellán, translation Francisco Giménez Gracia, Madrid, Espasa-Calpe, 1991. ISBN 84-239-7240-2.

- LOCKE, J., Various Works and Correspondence of (and over) John Locke. Selection, translation, introduction and notes by Carmen Silva and José Antonio Robles, Iztapalapa, Mexico, D., Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, 1991. ISBN 970-620-053-3.

- LOCKE, J., Thoughts on Education, Translation by Rafael Lassaletta, Madrid, Akal, 1986. ISBN 84-7600-095-2

- LOCKE, J., The Rationality of Christianity, translation of Leandro González Puertas, Madrid, Editions Paulinas, 1977. ISBN 84-285-0648-5.

- FILMER R. and LOCKE, J., The controversial Filmer-Locke on political obedienceed. Preliminary study by Rafael Gambra, translation Carmela Guitierrez de Gambra, ed. Political Classics, Madrid, Institute of Political Studies, 1966.

Contenido relacionado

Category:Rulers of Mexico

Flavian testimony

Michelangelo Antonioni