Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus of Nazareth, also called Christ, Jesus Christ or simply Jesus (province of Judea, Roman Empire, ca 4 BC-Jerusalem, Roman Empire, AD 30-33), was a Jewish religious leader and preacher. He is the central figure of Christianity and one of the most influential in history.

Currently and since the end of the 20th century, most historians of the Ancient Ages affirm the historical existence of Jesus. According to the opinion generally accepted in academic circles, based on a critical reading of the texts about his person, Jesus of Nazareth was a Jewish preacher who lived at the beginning of the first century in the regions of Galilee and Judea, and died crucified in Jerusalem around the year 30, under the government of Pontius Pilate.

The figure of Jesus is present in several religions. To most branches of Christianity, he is the Son of God, and by extension, the incarnation of God himself. His importance also lies in the belief that, with his death and subsequent resurrection, he redeemed mankind. Judaism denies his divinity, as it is incompatible with their conception of God. In Islam, where he is known as Isa, he is considered one of the most important prophets, while rejecting his divinity. Bahá'í teachings regard Jesus as a 'manifestation of God', a Bahá'í concept for prophets. Some Hindus consider Jesus to be an avatar or sadhu. Some Buddhists Jesus, including Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, regards Jesus as a bodhisattva who dedicated his life to the welfare of people.

What is known about Jesus comes almost exclusively from the Christian tradition —although he is mentioned in non-Christian sources—, especially that used for the composition of the synoptic gospels, written, according to the majority opinion, some thirty or forty years at least after his death. Most scholars consider that by studying the Gospels it is possible to reconstruct traditions that go back to Jesus' contemporaries, although there are great discrepancies among researchers regarding the methods of analysis of the texts and the conclusions that can be drawn from them..

Jesus in the New Testament

What follows is an account of the life of Jesus as it appears in the four gospels included in the New Testament, considered sacred books by all Christians. The evangelical story is the main source for the knowledge of Jesus, and constitutes the basis of the interpretations that the different branches of Christianity make of the figure of him. Although it may contain historical elements, it fundamentally expresses the faith of the Christian communities at the time these texts were written, and the vision they had of Jesus of Nazareth at that time.

Birth and infancy

The stories referring to the birth and childhood of Jesus come exclusively from the Gospel of Matthew (1,18-2,23) and from Luke (1,5-2,52). There are no such accounts in the Gospels of Mark and John. The narratives of Matthew and Luke differ from each other:

- The Gospel of Matthew does not relate any journey prior to the birth of Jesus, so it could be assumed that Mary and her husband Joseph lived in Bethlehem. Mary was unexpectedly pregnant and Joseph thought to repudiate her, but an angel told her in dreams that Mary's pregnancy was the work of the Holy Spirit and prophesied, with the words of the prophet Isaiah, that her son will be the Messiah that the Jews await. Some Eastern magicians on those dates came to Jerusalem asking for the “king of the Jews who have just been born” with the intention of worshiping him, alerting the king of Judea, Herod the Great, who decides to end the possible rival. The magicians, guided by a star, come to Bethlehem and worship the child. Again, the angel visited Joseph (Mt 2:13) and warned him of Herod's imminent persecution, so that the family flees to Egypt, remaining there until the death of the monarch (again notified to Joseph by the angel, who presented himself this way for the third time: Mt 2:19-29). Then Joseph returned and settled with his family in Nazareth in Galilee.

- In the Gospel of Luke, it is reported that Mary and Joseph live in the Galilean city of Nazareth. The history of Jesus' conception is intertwined here with that of John the Baptist—since in this gospel Mary and Elizabeth, the mother of the Baptist, are relatives—and the birth of Jesus is notified to Mary by the angel Gabriel (what is known as Annunciation: Lk 1:26-38). The Emperor Augustus then orders a census in which everyone must register in his place of birth, and Joseph must travel to Bethlehem, because he is originally from this place. Jesus is born in Bethlehem while they are on their journey and worshiped by pastors. Luke also adds brief accounts about the circumcision of Jesus, about his presentation in the Temple, and his meeting with the doctors in the Temple of Jerusalem, on a journey made on the occasion of the Passover, when he was twelve years old.

The genealogies of Jesus appear in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke (Mt 1, 2-16; Lk 3, 23-38). That of Matthew goes back to the patriarch Abraham, and that of Luke to Adam, the first man according to Genesis. These two genealogies are identical between Abraham and David, but they differ from the latter, since Matthew's makes Jesus a descendant of Solomon, while, according to Luke, his lineage would come from Natam, another of David's sons.. In both cases, what is shown is the ancestry of Joseph, despite the fact that, according to childhood accounts, this would only have been the adoptive father of Jesus.

His Hebrew birth name was Yeshua (יְשׁוּעַ), which means “Jehovah saves.” This name was very common, so we find several characters from the Bible, among them the high priest Joshua (Yehoshua = יְהוֹשׁוּעַ), who became a symbolic character after his death. This name came to Spanish from the Aramaic Yēšū'a, through the Greek Ἰησοῦς and the Latin Iesus. Therefore, Josué is a Hebrew-Aramaic adaptation, while Jesus is a Hellenization. In Nazareth he was known as Yeshua ben Jehoseph (Joshua/Jesus son of Joseph).

Baptism and temptations

The arrival of Jesus was prophesied by John the Baptist (his cousin, according to the Gospel of Luke), by whom Jesus was baptized in the Jordan River. During the baptism, the Spirit of God, in the form of a dove, descended on Jesus, and the voice of God was heard.

According to the Synoptic Gospels, the Spirit led Jesus into the desert, where he fasted for forty days and overcame the temptations to which he was subjected by the Devil. There is no mention of this episode in the Gospel of John. After Jesus went to Galilee, he settled in Capernaum, and began to preach the arrival of the Kingdom of God.

Public Life

Accompanied by his followers, Jesus toured the regions of Galilee and Judea preaching the gospel and performing many miracles. The order of the facts and sayings of Jesus varies according to the different evangelical accounts. It is also not stated how long Jesus' public life lasted, although the Gospel of John mentions that Jesus celebrated the annual Passover festival (Pesach) in Jerusalem on three occasions. Instead, the Synoptic Gospels mention only the Easter feast in which Jesus was crucified.

Many of the events in the public life of Jesus narrated in the Gospels take place in the northern area of Galilee, near the Sea of Tiberias, or Lake Genesaret, especially the city of Capernaum, but also other, like Corozain or Bethsaida. He also visited, in the south of the region, towns like Cana or Nain, and the village where he had grown up, Nazareth, where he was received with hostility by his former neighbors. His preaching also extended to Judea (according to John's Gospel, he visited Jerusalem three times since the beginning of his public life), and was in Jericho and Bethany (where he raised Lazarus from the dead).

He chose his main followers (called in the gospels "apostles"; in Greek, "envoys"), twelve in number, from among the people of Galilee. In the synoptics the following list is mentioned: Simon, called Peter and his brother Andrés; Santiago of Zebedeo and his brother Juan; Philip and Bartholomew; Thomas and Matthew the publican; Santiago the one of Alfeo and Tadeo; Simon the Zealot and Judas Iscariot, the one who would later betray Jesus (Mt 10,2-4; Mk 3,16-19; Lk 6, 13-16). Some of them were fishermen, like the two pairs of brothers formed respectively by Pedro and Andrés, and Juan and Santiago. Matthew is generally identified with Levi, the one from Alphaeus, a publican about whom in the three synoptics it is briefly related how he was called by Jesus (Mt 9,9; Mc 2,14; Lk 5,27-28). Jesus numerous reproaches from the Pharisees.

The Gospel of John only mentions the names of nine of the apostles, although in several passages it refers to their being twelve.

He preached both in synagogues and in the open air, and crowds flocked to hear his words. Among his speeches, the so-called Sermon on the Mount stands out, in the Gospel of Matthew (Mt 5-7). He often used parables to explain the Kingdom of God to his followers. The parables of Jesus are short stories whose content is enigmatic (they often have to be explained later by Jesus). They generally have an eschatological content and appear exclusively in the synoptic gospels. Among the best known are the parable of the sower (Mt 13,3-9; Mc 4,3-9; Lc 8,5-8), whose meaning Jesus explains below; that of the seed that grows (Mc 4,26-29); that of the mustard seed (Mt 13,31-32; Mc 4,30-32), that of the wheat and the tares (Mt 13,24-30), that of the lost sheep (Mt 18,12-14; Lc 15,3-7) and that of the lost coin (Lk 15,8-10), that of the ruthless servant (Mt 18, 23-35), that of the workers sent to the vineyard (Mt 20,1-16)., that of the two sons (Mt 21,28-32), that of the homicidal vinedressers (Mt 21,33-42; Mc 12,1-11; Lc 20,9-18); that of the wedding guests (Mt 22, 1-14), that of the ten virgins (Mt 25,1-13), that of the talents (Mt 25,14-30; Lk 19,12-27), that of the final judgment (Mt 25, 31-46). Two of the best known appear only in the Gospel of Luke: it is the parable of the good Samaritan (Lk 10,30-37) and that of the prodigal son (Lk 15,11-32). In the parables, Jesus frequently uses images related to peasant life.

He had controversies with members of some of the most important religious groups in Judaism, and especially with the Pharisees, whom he accused of hypocrisy and of not caring for the most important things in the Torah: justice, compassion and loyalty (Mt 12, 38-40; Lk 20, 45-47).

The authenticity of his message lay in his insistence on love for enemies (Mt 5,38-48; Lk 6, 27-36) as well as in his very close relationship with God, whom he called in Aramaic with the expression familiar Abba (Father) that neither Mark (Mc 14,36) nor Paul (Rm 8, 15; Gal 4, 6) translate. He is about a close god who seeks out the marginalized, the oppressed (Lk 4, 18) and sinners (Lk 15) to offer them his mercy. The Our Father prayer (Mt 6,9-13: Lk 11,1-4), which he recommended his followers use, is a clear expression of this close relationship with God mentioned above.

Miracles recounted in the Gospels

According to the gospels, during his ministry Jesus performed several miracles. In total, twenty-seven miracles are narrated in the four canonical gospels, of which fourteen are cures of different illnesses, five exorcisms, three resurrections, two natural prodigies and three extraordinary signs.

- The Gospels narrate the following miraculous healings by Jesus:

- He healed the fever of Peter's mother-in-law in his house in Capernaum, taking it by hand (Mk 1:29-31; Mt 5:14-15; Lk 4:38-39);

- He healed a Galilean leper by the word and contact of his hand (Mk 1:40-45; Mt 8.1-4; Lk 5:12-16);

- He healed a paralytic in Cafarnaum who was presented to him on a stretcher and who had forgiven his sins, ordering him to rise and go home (Mk 2:1-12; Mt 9:1-8; Lk 5:17-26);

- He healed a man with the dry hand on Saturday in a synagogue, by word (Mk 3:1-6; Mt 12.9-14; Lk 6:6-11);

- He healed a woman who had a flow of blood, who healed when she touched Jesus' dress (Mk 5:25-34; Mt 9:18-26; Lk 8:40-56);

- He healed a deaf mute in the Decapolis by putting his fingers in his ears, spitting, touching his tongue and saying, «Effatá»(Mk 7:31-37);

- He healed a blind man in Bethsaida by placing him saliva in his eyes and imposing his hands on him (Mk 8:22-26);

- He healed Bartimeus, the blind man of Jericho (Mt 20:29-34; Mk 10:46-52; Lk 18:35-45);

- He healed the servant of the centurion of Capernaum (Mt 8.5-13, Lc 7,1-10, Jn 4,43-54; Jn 4,43-54);

- He healed a woman who was in bondage and could not be straightened, by word and laying hands (Lk 13:10-17). This healing also took place on Saturday and in a synagogue;

- He healed a hydropic on Saturday, at the house of one of the main Pharisees (Lk 14:1-6).

- He healed ten lepers, who found on his way to Jerusalem, through the word (Lk 17:11-19).

- He healed a man who had been sick for thirty-eight years in Jerusalem on Saturday (Jn 5:1-9).

- He healed a blind man by uniting him with sludge and saliva, after which he ordered to wash himself in the pool of Siloé (Jn 9:1-12).

- He healed the ear of a high priest's servant (Lk 22,51)

- In the canonical Gospels there are five accounts of expulsions of unclean spirits (exorcised) made by Jesus:

- Expulsed a demon in the synagogue of Capernaum (Mk 1,21-28; Lk 4,31-37);

- Expulsed another in the Gerasa region (Mt 8:28-34; Mk 5.1-21; Lk 8:26-39);

- He expelled another who possessed the daughter of a Syrophenian woman (Mt 15:21-28; Mk 7:24-30);

- He expelled another who tormented an epileptic (Mt 17,20-24; Mk 9,14-27; Lk 9,37-43);

- He expelled a "murdered devil" (Lk 11,14; Mt 12,22).

In addition, there are several passages that refer generically to exorcisms of Jesus (Mc 1,32-34;Mc 3,10-12).

- According to the Gospels, Jesus did three resurrections:

- He raised a twelve-year-old girl, Jairus' daughter (Mk 5:21-24, Mt 9:18-26, Lk 8:40-56). Jesus said that the child was not dead, but only asleep (Mt 9:24; Mk 5:39; Lk 8:52).

- He raised the son of the widow of Nain (Lk 7:11-17).

- He raised Lazarus from Bethany (Jn 11:1-44).

- Jesus also obeyed, according to the gospels, two natural wonders, in which the obedience of natural forces (the sea and the wind) is revealed to his authority.

- Jesus commanded the storm to calm down and obey it (Mt 8:23-27; Mk 4,35-41; Lk 8,22-25).

- Jesus walked over the waters (Mt 14,22-33; Mk 6,45-52; Jn 6,16-21).

- Three extraordinary signs, which make a sharply symbolic sense:

- Multiplication of breads and fish. He is the only one of all the miracles of Jesus that is recorded by all the gospels (Mk 6:32-44; MtS14.13-21; Lk 9.10-17; Jn 6:1-13). It occurs twice according to the Gospel of Mark (8.1-10) and the Gospel of Matthew (15.32-39);

- miraculous fishing (Lk 5:1-11; Jn 21:1-19);

- the conversion of water into wine at the weddings of Cana (Jn 2:1-11).

In those times, the scribes, Pharisees and others attributed this power to expel demons to a conspiracy with Beelzebub. Jesus vigorously defended himself against these accusations.According to the Gospel accounts, Jesus not only had the power to cast out demons, but he passed that power on to his followers. There is even mention of a man who, not a follower of Jesus, successfully cast out demons in his name.

Transfiguration

The synoptic gospels relate that Jesus went up a mountain to pray with some of the apostles, and while he was praying the appearance of his face was transformed, and his dress became white and resplendent. Moses and Elijah appeared next to him. The apostles slept meanwhile, but when they woke up they saw Jesus next to Moses and Elijah. Peter suggested that they make three tents: for Jesus, Moses, and Elijah. Then a cloud appeared and a heavenly voice was heard, which said: "This is my chosen Son, listen to him." The disciples did not tell what they had seen.

Passion

Entry into Jerusalem and purification of the Temple

According to the four gospels, Jesus went with his followers to Jerusalem to celebrate the Passover festival there. He entered on the back of a donkey, so that the words of the prophet Zechariah would be fulfilled (Zc 9, 9: "Behold, your king comes to you, meek and mounted on a donkey, on a colt, the son of a beast of burden"). He was received by a crowd, who hailed him as "son of David" (in contrast, according to the Gospel of Luke, he was hailed only by his disciples). In the Gospel of Luke and in that of John, Jesus is hailed as king.

According to the Synoptic Gospels, he then went to the Temple of Jerusalem, and drove out the money changers and the sellers of animals for ritual sacrifices (the Gospel of John, on the other hand, places this episode at the beginning of the life of Jesus, and links it to a prophecy about the destruction of the Temple). He predicted the destruction of the Temple and other future events.

Anointing in Bethany and Last Supper

In Bethany, near Jerusalem, he was anointed with perfume by a woman. According to the synoptics, on Easter night he dined in Jerusalem with the Apostles, in what Christian tradition designates as the Last Supper. During this paschal meal, Jesus predicted that he would be betrayed by one of the Apostles, Judas Iscariot. He took bread in his hands, saying "Take and eat, this is my body" and then, taking a chalice of wine, he said: "Drink from it, all of you, for this is the blood of the Covenant, which will be shed by the multitude for the remission of sins." He also prophesied, according to the synoptics, that he would not drink wine again until he drank it again in the Kingdom of God.

Arrest

After dinner, according to the Synoptics, Jesus and his disciples went to pray in the Garden of Gethsemane. The apostles, instead of praying, fell asleep, and Jesus suffered a moment of strong anguish regarding his fate, even though he decided to abide by God's will.

Judas had indeed betrayed Jesus, to hand him over to the chief priests and elders of Jerusalem in exchange for thirty pieces of silver. Accompanied by a group armed with swords and clubs, sent by the high priests and elders, he arrived at Gethsemane and revealed Jesus' identity by kissing him on the cheek. Jesus was arrested. On the part of his followers there was an attempt to resist, but finally they all dispersed and fled.

Judgment

After his arrest, Jesus was taken to the palace of the high priest Caiaphas. There he was tried before the Sanhedrin. False witnesses were presented, but since his testimonies did not match, they were not accepted. Finally, Caiaphas asked Jesus directly if he was the Messiah, and Jesus said, "You have said it." The high priest tore his garments at what he considered blasphemy. Members of the Sanhedrin cruelly mocked Jesus. In the Gospel of John, Jesus was brought first to Annas, Caiaphas's father-in-law, and then to the latter. Only the interrogation before Annas is detailed, quite different from that which appears in the synoptics. Peter, who had secretly followed Jesus after his arrest, was hiding among the servants of the high priest. Recognized as a disciple of Jesus by the servants, he denied him three times (twice according to the Gospel of John), as Jesus had prophesied.

The next morning, Jesus was brought before Pontius Pilate, the Roman procurator. After questioning him, Pilate found him not guilty, and asked the crowd to choose between releasing Jesus or a known bandit named Barabbas. The crowd, persuaded by the chief priests, called for Barabbas to be released, and for Jesus to be crucified. Pilate symbolically washed his hands to express his innocence of Jesus' death.

Crucifixion

Jesus was scourged, they dressed him in a red cloak, they put a crown of thorns on his head and a reed in his right hand. The Roman soldiers taunted him saying, "Hail, King of the Jews." He was forced to carry the cross on which he was to be crucified to a place called Golgotha, which in Aramaic means 'place of the skull'. He was helped to carry the cross by a man named Simon of Cyrene.

They gave Jesus drink wine with gall. He tasted but did not want to take it. After crucified, soldiers divided his garments. On the cross, on their head, they put a sign in Aramaic (יֵשׁוּעַ נָצְרַת מלך היהודים [ Yeshu'a hanatzrat melech hayehudim ' reason for his condemnation: "This is Jesus, the King of the Jews", which is often abbreviated INRI in paintings (Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum, literally 'Jesus Nazarene, the King of the Jews'). He was crucified between two thieves.

Around three in the afternoon, Jesus exclaimed: "Eli, Eli, lemma sabactani", which, according to the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Mark, in Aramaic means: 'My God, my God, why did you have you given up?' Jesus' final words differ in the other two gospels.There is also a difference between the gospels as to which of Jesus' disciples were present at his crucifixion: in Matthew and Mark, they are several of Jesus' female followers; In the Gospel of John, the mother of Jesus and the "disciple whom he loved" are also mentioned (according to Christian tradition, it would be the apostle John, although his name is not mentioned in the gospel text).

Burial

A follower of Jesus, named Joseph of Arimathea, asked Pilate for the body of Jesus on the same Friday afternoon that he had died, and he deposited it, wrapped in a sheet, in a tomb carved out of the rock. He covered the grave with a large stone. According to the Gospel of Matthew (not mentioned in the other Gospels), the next day the "chief priests and Pharisees" asked Pilate to post an armed guard in front of the tomb, to prevent Jesus' followers from stealing his grave. body and spread the rumor that he had risen. Pilate agreed.

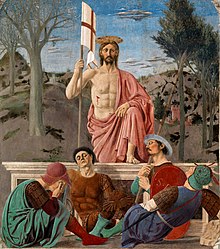

Resurrection and Ascension

All four gospels relate that Jesus rose from the dead on the third day after his death and appeared to his disciples on several occasions. In all of them, the first to discover the resurrection of Jesus is Mary Magdalene. Two of the gospels (Mark and Luke) also recount his ascension to heaven. Accounts of the risen Jesus vary, however, depending on the gospels:

- In the Gospel of Matthew, Mary Magdalene and "the other Mary" went to the tomb on Sunday morning. An earthquake came, and an angel dressed in white removed the stone from the tomb and sat on it. The guards, who witnessed the scene, trembled in fear and "were as dead" (Mt 28:1-4). The angel announced to the women the resurrection of Jesus, and entrusted them to tell the disciples to go to Galilee, where they could see him. Upon returning, Jesus himself came to meet them, and repeated to them that they would tell the disciples to go to Galilee (Mt 28:5-10). Meanwhile, the guards warned the chief priests of what happened. They bribed them to spread the idea that the disciples of Jesus had stolen their body (Mt 28:11-15). The eleven apostles went to Galilee, and Jesus commissioned them to preach the gospel (Mt 28:16-20).

- In the Gospel of Mark, three followers of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, Mary of James and Salome, went to the tomb on Sunday morning, with the intention of anointing Jesus with perfumes (Mk 16:1-2). They saw that the stone that covered the tomb was removed. Within the tomb, they discovered a young man dressed in a white robe, who announced to them that Jesus had risen, and commanded them to tell the disciples and Peter to go to Galilee to see Jesus. It is indicated that Mary and her companions said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid (Mk 16:3-8). Then it is said that Jesus appeared to Mary Magdalene (not to mention other women), and that this gave the rest of Jesus' followers the good news, but it was not believed (Mk 16:9-11). Jesus appeared again, this time to two who were on their way: when these disciples told what happened, they were not believed (Mk 16:12-13). Finally, he appeared to the eleven apostles, whom he rebuked for not believing in his resurrection. He entrusted them with preaching the gospel, and went up to heaven, where he sat on the right hand of God (Mk 16:14-20).

- In the Gospel of Luke, some women, Mary Magdalene, Joan and Mary of James, and others whose names are not mentioned, came to the tomb to anoint Jesus with perfumes. They found the stone removed from the tomb, entered it and did not find the body (Lk 24:1-3). Then two men appeared to them with dazzling garments, who announced to them the resurrection of Jesus (Lk 24:4-7). The women announced the resurrection to the apostles, but these did not believe them (Lk 24:8-11), except Peter, who went to the tomb and found that the body had disappeared (Lk 24:12). On the same day, Jesus appeared to two disciples who walked from Jerusalem to Emmaus, who recognized him at the time of the breaking of the bread (Lk 24:13-35). Shortly afterwards he appeared before the eleven, who believed that it was a spirit, but showed them that it was he in flesh and bones, and ate in his presence (Lk 24:36-43). He explained to them the meaning of his death and resurrection (Lk 24:44-49), and later brought them near Bethany, where he ascended to heaven (Lk 24:50-53).

- In the Gospel of John, Mary Magdalene went to the tomb very early and discovered that the stone had been removed. He ran in search of Peter and of the "disciple whom Jesus loved" to warn them (Jn 20:1-2). They both ran to the tomb. The beloved disciple came first, but did not enter the tomb. Peter entered first and saw the fajas and the sweatshop, but not the body. The other disciple then entered, "and saw and believed" (Jn 20:3-10). Magdalene stayed outside, and two angels appeared in white. They asked him, "Why are you crying, woman?" and she answered, "Because they have taken my Lord and I don't know where they have put him." He turned back, and saw Jesus risen, who in turn asked him why he was crying. Magdalena confused him with the hortelane, and asked him where he had put Jesus. Jesus called her: “Mary!” and she recognized him, answering: "Rabbuní!". Jesus asked him not to touch him, for he had not yet gone up to the Father, and asked his brothers to warn him that he would go up to the Father. Magdalena went to announce what happened to the disciples (Jn 20:11-18). That same day, in the afternoon, Jesus appeared to the place where the disciples were hidden for fear of the Jews. He greeted them saying, "Peace be with you," he showed them the hand and side, and, blowing, he sent them the Holy Spirit. One of the eleven, Thomas, was not with the rest when the appearance of Jesus took place, and did not believe that the appeared was really Jesus (Jn 20:19-25). Eight days later, Jesus appeared again to all the disciples, including Thomas. To overcome his unbelief, Jesus told him to touch his hand and side. Thomas believed in him (Jn 20, 26-29). Later, Jesus appeared again to seven of his disciples when they were fishing by the sea of Tiberiades. They had no fish; they asked them to throw the net back and they took it full of fish. Then they recognized him, and ate with him breads and fishes (Jn 21:1-14). After this, there is a conversation between Jesus and Peter, in which the "loved disciple" also intervenes (Jn 21:15-23).

Old Testament Prophecies Concerning Jesus

According to the authors of the New Testament, the life of Jesus supposed the fulfillment of some prophecies formulated in certain books of the Old Testament. The biblical books most cited in this sense by the early Christians were Isaiah, Jeremiah, the Psalms, Zechariah, Micah, and Hosea. For the authors of the New Testament, in a vision shared by later Christians, these texts announce the coming of Jesus of Nazareth, who would be the Messiah expected by the people of Israel. Often the writers of the gospels, especially the author of the Gospel of Matthew, explicitly quote these texts to underline the fulfillment of these prophecies in the life and death of Jesus. Among other things, they consider that the circumstances and place of Jesus' birth were prophesied (Is 7,14; Miq 5,2); his relationship with Galilee (Is 9,1); his messianic condition (Is 9, 6 -7; Is 11, 1-9; Is 15, 5); the role of precursor of John the Baptist (Is 40,3) and even his passion and sacrificial death (in this regard, four poems are cited above all, included in Deutero Isaiah (or Second Isaiah), which present the figure of a servant of Yahweh, to whose sacrifice a redemptive value is attributed, but also many other passages.

The Jews, who also hold these books sacred, do not accept the Christian belief that these prophecies refer to Jesus of Nazareth. For current historical research, the main question is to what extent these books helped shape the gospel accounts.

Jesus according to historical research

In the current state of knowledge about Jesus of Nazareth, the prevailing opinion in academic circles is that he is a historical figure, whose biography and message were modified by the writers of the sources. He exists, without However, a minority of scholars who, from a radical criticism of the sources, consider it likely that Jesus was not even a real historical figure, but a mythical entity, similar to other cult figures in antiquity.

Fonts

It is above all Christian sources, obviously partial, that provide information about Jesus of Nazareth. Christian texts mainly reflect the faith of primitive communities, and cannot be considered, without more, historical documents.

The texts in which current criticism believes it is possible to find information about the historical Jesus are mainly the three synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke). Secondarily, they also provide information about Jesus of Nazareth other New Testament writings (the Gospel of John, the epistles of Paul of Tarsus), some apocryphal gospels (such as Thomas and Peter), and other Christian texts.

On the other hand, there are references to Jesus in a few non-Christian works. In some cases the authenticity of him has been questioned (Flavio Josefo), or that they refer to the same character whose life is recounted by the Christian sources (Suetonius). They hardly give any information, except that he was crucified in the time of Pontius Pilate (Tacitus) and that he was considered a trickster by orthodox Jews.

Philological research has managed to reconstruct the history of these texts with a high degree of probability, which leads to the conclusion that the first texts about Jesus (some of Paul's letters) are some twenty years later than the probable date of his birth. death, and that the main sources of information about his life (the canonical gospels) were written in the second half of the I. There is a broad consensus about this chronology of sources, just as it is possible to date some (very scant) testimonies about Jesus in non-Christian sources to the last decade of the I and the first quarter of the II century.

Christian fonts

There are many Christian writings from the I and II in which references to Jesus of Nazareth are found. However, only a small part of them contains useful information about him. All of them reflect, first of all, the faith of the Christians of the time, and only secondarily reveal biographical information about Jesus.

The main ones are:

- The Letters from Paul of Tarsus: written, according to the most probable date, between the 50s and 60s. They are the earliest documents about Jesus, but the biographical information they provide is scarce.

- Them Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke), included by the Church in the Canon of the New Testament. In general, they usually date between the 1970s and 90s. They provide a lot of information, but they mainly reflect the faith of early Christians, and are rather late documents.

- The Gospel of Johnalso included in the New Testament. It was probably written about 90-100. It is often considered less reliable than the synoptics, as it presents much more evolved theological conceptions. However, it cannot be excluded that it contains traditions about the historical Jesus much older.

- Some of the calls Apocryphal Gospelsnot included in the canon of the New Testament. A large part of these texts are very late documents that do not provide information about the historical Jesus. However, some of them, whose dating is quite controversial, could transmit information about Jesus' sayings or facts: among those to whom greater credibility is often given are the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel Egerton, the Secret Gospel of Mark and Gospel of Peter.

The letters of Paul of Tarsus

The oldest known texts relating to Jesus of Nazareth are the letters written by Paul of Tarsus, considered to predate the gospels. Paul did not personally know Jesus. His knowledge of him and his message, according to his own statements, can come from a double source: on the one hand, he maintains in his writings that the risen Jesus himself appeared to him to reveal his gospel, a revelation to which Paul granted great importance (Gal 1, 11-12); on the other, also according to his own testimony, he maintained contacts with members of various Christian communities, including several followers of Jesus. He met, as he himself states in the Epistle to the Galatians, Peter (Gal 2, 11-14), John (Gal 2, 9), and James, whom he refers to as "the brother of the Lord" (Gal 1, 18-19; 1 Cor 15, 7).

Although Christian tradition attributes to Paul fourteen epistles included in the New Testament, there is only consensus among current researchers regarding the authenticity of seven of them, which are generally dated between the years 50 and 60 (First Epistle to the Thessalonians, Epistle to the Philippians, Epistle to the Galatians, First Epistle to the Corinthians, Second Epistle to the Corinthians, Epistle to the Romans, and Epistle to Philemon). These epistles are letters addressed by Paul to Christian communities in different parts of the Roman Empire, or to particular individuals. They mainly deal with doctrinal aspects of Christianity. Paul is interested above all in the sacrificial and redemptive meaning that, according to him, the death and resurrection of Jesus have, and his references to the life of Jesus or the content of his preaching are few.

However, the Pauline epistles do provide some information. In the first place, they affirm that Jesus was born "according to the Law" and that he was of the lineage of David, "according to the flesh" (Rom 1:3), and that the addressees of his preaching were circumcised Jews (Rom 15, 8). Secondly, it refers to certain details about his death: it indicates that he died crucified (2 Cor 13, 4), that he was buried and that he rose again on the third day (1 Cor 15, 3-8), and attributes his death to the Jews. (1 Thes 2, 14) and also to the "mighty of this world" (1 Cor 2, 8). In addition, the First Epistle to the Corinthians contains an account of the Last Supper (1 Cor 11, 23-27), similar to that of the Synoptic Gospels (Mt 26, 26-29; Mc 14, 22-25; Lk 22, 15 -20), though probably older.

Synoptic Gospels

Scholars agree that the main source of information about Jesus is found in three of the four gospels included in the New Testament, the so-called synoptics: Matthew, Mark and Luke, whose writing is generally between the years 70 and 100.

The dominant view in current criticism is that the gospels were not written by personal witnesses to Jesus' activity. They are believed to have been written in Greek by authors who had no direct knowledge of the historical Jesus. Some authors, however, continue to hold the traditional point of view on this issue, which attributes them to characters quoted in the New Testament.

Although it is not accepted by all critics, the affinities between these gospels are usually explained by the so-called theory of the two sources, proposed as early as 1838 by C. H. Weisse, and which was later significantly qualified by B. H. Streeter in 1924 According to this theory, the oldest gospel is Mark (and not Matthew, as previously believed). Both Luke and Matthew are later, and used Mark as their source, which explains the common material among the three synoptics, called "of triple tradition." But, in addition, there was a second source, which was given the name Q, which contained almost exclusively Jesus' words, which explains the so-called double-traditional material, which is found in Matthew and Luke, but not in Mark (Q is today considered an independent document, of which there are even critical editions). Finally, both Luke and Matthew contain their own material, which is not found in either of the two hypothetical sources.

The degree of reliability given to the gospels depends on the scholars. The most widespread opinion is that they are mainly apologetic texts, that is, religious propaganda, whose main intention is to spread an image of Jesus in accordance with the faith of the primitive Christian communities, but that they contain, to a greater or lesser extent, data about the Historical Jesus. It has been shown that they contain several historical and geographical errors, numerous narrative inconsistencies and abundant supernatural elements that are undoubtedly expressions of faith and of which it is disputed whether or not they have a historical origin. However, they place Jesus in a plausible historical setting, generally consistent with what is known from non-Christian sources, and outline a fairly coherent biographical trajectory.

The current of research called «history of forms», whose main representatives were Rudolf Bultmann and Martin Dibelius, was oriented above all to study the literary «prehistory» of the gospels. These authors determined that the gospels (including Q, considered a "protoevangelium") are compilations of minor literary units, called pericopes, belonging to different literary genres (narrations of miracles, didactic dialogues, ethical teachings, etc.). These pericopes have their ultimate origin in the oral tradition about Jesus, but only some of them refer to true sayings and facts of the historical Jesus. Later, another school, called «redaction history» (or redaction criticism), highlighted the fact that, when it came to compiling and narratively unifying the material available to them, the authors of the Gospels responded to theological motivations..

In dating the Synoptic Gospels, one aspect of particular importance is the references to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. Studying these references, most authors agree that the three synoptics, in their current state, date from after the destruction of the temple (year 70), while Q is most likely earlier.

The authors of the gospels respond to specific theological motivations. In their works, they try to harmonize received traditions about the historical Jesus with the faith of the communities to which they belong.

- Source Q: the existence of this protoevangelium, as has been said before, has been induced from the textual research of the affinities between the synoptics. At present, much progress has been made in rebuilding this hypothetical text. It is believed that it was written in Greek, which contained primarily the sayings of Jesus, and that it was written, probably in Galilee at a time before the first Jewish-Roman war, probably between the 40s and 60s. As for its content, significant parallels have been found between Q and an apocryphal gospel of difficult dating, the Gospel of Thomas.

- Gospel of Mark: it was written in Greek, possibly in Syria, or perhaps in Rome, and is usually dated around the year 70, so it is the oldest gospel that is preserved. It is basically considered a collection of materials of written and oral tradition, among which stands out, for its structural unity, the narrative of the Passion, but which also include anthologies of miracles, apocalyptic traditions (especially Mc 13) and school disputes and dialogues.

- Gospel of Matthew: it was written in Greek, possibly in Syria, and it is more late than Marcos, whom he uses as a source. It was probably written in the 80s of the century. I. It combines as sources Q, Mark, and others, and its main intention is to highlight the figure of Jesus as the fullness of the Law and the prophets of the Old Testament, so it uses abundantly quotes from the Jewish Scriptures. The text of Mt 13, 44: 'The kingdom of heaven is like a treasure hidden in a field that, when a man finds it, hides it again and, by the joy that gives it, sells all that has and buys the field that', becomes sense in the framework of the property of the earth in Rome, which was, upward: 'ad astra', and downward: 'ad inferos', so a treasure found

- Gospel of Luke: is the first part of a unitary work whose second part is the text known as Acts of the Apostles, dedicated to narrating the origins of Christianity. Like Matthew, he uses as Q and Marcos sources.

Gospel of John

The Gospel of John is generally considered to be later than the Synoptics (usually dating to around the year 100) and the information it provides about the historical Jesus is less reliable. It shows a more developed theology, since it presents Jesus as a pre-existent being, substantially united to God, sent by him to save the human race. However, it seems that its author used ancient sources, in some cases independent of the synoptics, for example, regarding the relationship between Jesus and John the Baptist, and the trial and execution of Jesus. He recounts few miracles of Jesus (only seven), for which he possibly used a hypothetical Gospel of Signs as a source. In this gospel there are many scenes from the life of Jesus that have no parallel in the synoptics (including some of the best known, such as the wedding at Cana or the resurrection of Lazarus from Bethany).

Apocryphal Gospels

Apocryphal gospels are those texts about facts or sayings of Jesus not included in the New Testament canon. As Antonio Piñero points out, most of the apocrypha do not provide valid information about the historical Jesus, since they are quite late texts (after 150), and that use the canonical gospels as sources.

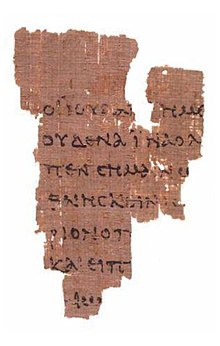

There are, however, some notable exceptions: the Gospel of Peter, the Egerton Papyrus 2, the Oxyrhynchus Papyri and, very especially, the Gospel of Thomas. There is no agreement among specialists about the dating of these texts, but the majority position is that they may contain authentic information about Jesus. Given their fragmentary nature, however, they have been used above all to confirm information that is also transmitted by the canonical gospels.

Other Christian texts

- Those attributed to Jesus in other New Testament books: these sayings are conventionally called agrapha, that is to say ‘not written’. Leaving aside the letters of Paul, already mentioned, are those attributed to Jesus in Acts of the Apostles (20, 35); Epistle of Santiago and in the First Epistle of Peter.

- References of other Christian writers of the centuries II and IIIamong which the first and Second Epistle of Clementthe letters of Ignatius of Antioch; and a lost text, attributed to Papías de Hierápolis, entitled Exposition of the words of the Lord, which supposedly collected oral traditions about Jesus, and of which only fragments are known by quotations from subsequent authors, such as Ireneo de Lyon and Eusebio de Cesarea.

The historicity of these references is generally considered quite dubious.

Non-Christian Sources

There are hardly any mentions of Jesus in non-Christian sources from the I and II. No historian dealt extensively with his story: there are only passing allusions, some of them ambiguous, and one of Flavius Josephus's (the so-called "Flavian Testimony") possibly contains some later interpolation. However, all of them together are enough to certify his historical existence. In this regard The New Encyclopaedia Britannica states:

These independent accounts show that in Antiquity not even the opponents of Christianity doubted the historicity of Jesus, which began to be put into question, without any basis, at the end of the century XVIIIalong the 19th and early 20th.The New Encyclopaedia Britannica

These sources can be divided into:

Jewish Sources

- Two mentions in a work by the Jewish historian Flavio Josefo, Antiquities Jews.

The first passage of the aforementioned work that mentions Jesus is known as the «Flavian testimony». Found in Jewish Antiquities, 18.3.3. It was the subject of later interpolations by Christian copyists, and for many years it was debated whether Josephus even alluded to Jesus in its original version. This debate was resolved in 1971, when an Arabic manuscript from the X century appeared in which Bishop Agapius of Hierapolis quoted that text. of Josephus. Since the first copy of Josephus in possession (that of the Ambrosiana) dates from the XI century, a century later, It must be admitted that the Arabic text, above, reproduces that of Josephus without interpolations.

The second passage has not usually been discussed, as it is closely related to the context of the work and seems unlikely to be an interpolation. It is found in Jewish Antiquities, 20.9.1, and refers to the stoning of James, who the text identifies as the brother of Jesus, a character who is called the same way in some texts by Paul of Tarsus. Although without absolute consensus, for most of the authors the passage is authentic.

- Issues in the treaty Sanhedrin of the Babylonian Talmud: it is not clear whether these passages refer to Jesus of Nazareth. In Sanh.43 a. It is said that Yeshu was hung “the Easter Eve”, for having practiced sorcery and for inciting Israel to apostasy. Even the name of five of his disciples is mentioned: Matthai, Nakai, Nezer, Buni and Todah. Most scholars date this reference very late, and do not consider it an independent source of information.

Roman and Syrian sources

Brief mentions in two works by Suetonius (c. 70-post 126), Tacitus (61-117) and Pliny the Younger (62-113). Except for Tacitus, they are rather references to the activity of Christians:

- Suetonius about 120 AD, but according to a note apparently taken from a document of the police of the time of Claudius (41-54 AD), mentions the Christians, and in another passage of the same work, speaking of the same emperor, says that "the Jews, instigated by the Jews, ChrestusHe expelled them from Rome because of their scandalous habits" (Vita Caesarum. Divus Claudius25). The Hebrews were expelled from Rome, guilty of having caused tumults under the instigation of such a "Chrestus". Another version of the same text indicates that Claudio: "He expelled the Jews from Rome because of the continuing struggles caused by such a "Crest." The name Chrestus has been interpreted as a poor reading of Christus; however, it cannot be excluded that the passage refers to a Jewish agitator in the Rome of the 1950s.

- 116 or 117, the Tacite historian, in his Anales Speaking of the reign of Nero (54-58 A.D.), he commented that after the fire of Rome he inflicted severe pain on the followers of a Christ, who had been supplicated under Pontius Pilate: the Christians took his name “from a Christ, who at the time of Tiberius was adjusted by Pontius Pilate” (Plate).Anales15.44:2-3).

- At the beginning of the century IIPliny the Young, in a letter to Emperor Trajan (98-117 AD), mentions that "these Christians (those who appear before themselves) who consent to make sacrifices to the gods, absolve them. On the other hand, they claim that they have done no evil: they simply say that they have raised chants to Christ, like those who dedicate themselves to a god, "they sing hymns to Christ (almost God, as they say)" (Epistles 10:96).

There are some other texts, such as that of Lucian of Samósata (second half of the II century AD..), which mentions "that man whom they continue to adore, who was crucified in Palestine... that crucified sophist", or another that, although it is doubtful, could be a reference to Jesus of Nazareth: it is a letter, preserved in Syriac, written by one Mara Bar-Serapion, which speaks of a "wise king" sentenced to death by the Jews. Whether this letter dates from the I, II or III of our era, and neither it is clear whether or not it is a reference to Jesus of Nazareth.

The paucity of non-Christian sources suggests that Jesus' activity did not attract attention in his time, although according to Christian sources his preaching would have drawn crowds. Non-Christian sources provide only a very schematic image of the knowledge of Jesus as a historical figure.

Archaeology

Archaeology does not present evidence to verify the existence of Jesus of Nazareth. The main explanation given for this fact is that Jesus did not reach enough relevance while he was alive to be recorded in archaeological sources, since he was not an important political leader, but a simple itinerant preacher. Although archeology findings cannot be adduced as proof of the existence of Jesus of Nazareth, they do confirm the historicity of a large number of characters, places, and events described in the sources.

On the other hand, Jesus, like many prominent ancient religious leaders and philosophers, wrote nothing, or at least there is no record that he did. All the sources for the historical investigation of Jesus of Nazareth are, therefore, texts written by other authors. The oldest document unequivocally concerning Jesus of Nazareth is the so-called Papyrus P52, which contains a fragment of the Gospel of John and which dates, according to the most widespread calculations, from approximately 125 (that is, almost a century after the possible date of Jesus' death, around the year 30).

Methodology

The historical investigation of the Christian sources on Jesus of Nazareth requires the application of critical methods that allow us to discern the traditions that go back to the historical Jesus from those that constitute later additions, corresponding to the primitive Christian communities.

The initiative in this search came from Christian researchers. During the second half of the XIX century, his main contribution focused on the literary history of the Gospels.

The main criteria on which there is a consensus when interpreting Christian sources are, according to Antonio Piñero, the following:

- Criterion of dislike or dissimilarity: according to this criterion, certain facts or sayings attributed to Jesus may be given in the sources that are contrary to the conceptions or interests of Judaism before Jesus or of Christianity after him. Against this criterion, objections have been made, since, by dissociating Jesus from the Judaism of the Century Iis at risk of depriving him of the context necessary to understand several fundamental aspects of his activity.

- Criterion of difficulty: those facts or sayings attributed to Jesus may also be considered authentic to be uncomfortable for the theological interests of Christianity.

- Multiple Testification Criterion: those facts or sayings of Jesus may be considered authentic from those that may be claimed to come from different strata of tradition. In this regard, it is often considered that, at least partially, they provide independent sources among themselves Q, Mark, Luke's own material, Matthew's own material, John's Gospel, certain apocryphal Gospels (very especially, in relation to the sayings, the Gospel of Thomasbut also others like Gospel of Peter or Gospel Egertonand others. This criterion also refers to the attestation of the same saying or done in different forms or literary genres.

- Consistency or consistency: may also be given by certain such or facts that are consistent with what the above criteria have allowed to establish as authentic.

- Criterion of historical plausibility: according to this criterion, what is plausible in the context of the Judaism of the century can be considered historical Ias well as that which can contribute to explain certain aspects of the influx of Jesus in the early Christians. As Piñero points out, this criterion contradicts desemejanza, stated in the first place.

Not all authors, however, interpret these criteria in the same way, and there are even those who deny the validity of some of them.

Context

Historical framework

The Jewish people, without a state of their own since the destruction of the First Temple in 587 B.C. C., in the time of Nebuchadnezzar II, had spent several decades successively subjected to Babylonians, Persians, the Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt and the Seleucid Empire, without serious conflicts. In the 2nd century B.C. C., however, the Seleucid monarch Antiochus IV Epiphanes, determined to impose the Hellenization of the territory, desecrated the Temple. This attitude triggered a rebellion led by the priestly family of the Maccabees, who established a new Jewish kingdom with complete independence from the year 134 B.C. C. until 63 a. c.

In that year, the Roman general Pompey intervened in the civil war between two brothers from the Hasmonean dynasty, Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II. With this intervention began the Roman rule in Palestine. Said domain, however, was not always exercised directly, but through the creation of one or more client states, which paid tribute to Rome and were obliged to accept its directives. Hyrcanus II himself was kept by Pompey at the head of the country, although not as king, but as an ethnarch. Later, after an attempt to recover the throne from the son of Aristobulus II, Antigonus, who was supported by the Parthians, the trusted man of Rome was Herod, who did not belong to the family of the Hasmoneans, but was the son of Antipater, a general of Hyrcanus II of Idumean origin.

Following his victory over the Parthians and the followers of Antigonus, Herod was made king of Judea by Rome in 37 B.C. C. his reign, during which, according to the majority opinion, the birth of Jesus of Nazareth took place, was a relatively prosperous period.

On the death of Herod, in 4 B.C. C., his kingdom was divided among three of his sons: Archelaus was appointed ethnarch of Judea, Samaria and Idumea; to Antipas (called Herod Antipas in the New Testament) the territories of Galilee and Perea corresponded to him, which he ruled with the title of tetrarch; Finally, Philip inherited, also as tetrarch, the most remote regions: Batanea, Gaulanítide, Traconítide and Auranítide.

These new rulers would meet mixed fates. While Antipas remained in power for forty-three years, until 39, Archelaus, due to the discontent of his subjects, was deposed in 6 d. C. by Rome, which went on to directly control the territories of Judea, Samaria and Idumea.

In the period in which Jesus carried out his activity, therefore, his territory of origin, Galilee, was part of the kingdom of Antipas, responsible for the execution of John the Baptist, and to which a late tradition, which was only found in the Gospel of Luke, plays a secondary role in the trial of Jesus. Judea, on the other hand, was administered directly by a Roman official, belonging to the equestrian order, who first carried the title of prefect (until the year 41) and then (from 44) that of procurator. In the period of Jesus' activity, the Roman prefect was Pontius Pilate.

The prefect did not reside in Jerusalem, but in Caesarea Maritima, a city on the Mediterranean coast that had been founded by Herod the Great, although he traveled to Jerusalem on some occasions (for example, on the occasion of the Pesach or Easter festival, as recounted in the gospels, since it was during these festivals, when thousands of Jews gathered, when riots used to take place). He had a relatively small military force (about 3,000 men), and his authority was subject to that of the Syrian legate. In the time of Jesus, the prefect had the exclusive right to pass sentences of death (ius gladii).

However, Judea enjoyed a certain level of self-government. In particular, Jerusalem was governed by the authority of the high priest, and the council of him or the Sanhedrin. The exact powers of the Sanhedrin are controversial, although it is generally accepted that, except in very exceptional cases, they did not have the power to judge capital crimes.

The particular character of Galilee

Although separated from Judea by history, Galilee was in the I century a region of Jewish religion. It had, however, some differential features, such as a lesser importance of the Temple, and a lesser presence of religious sects such as the Sadducees and the Pharisees. It was very exposed to Hellenistic influences and presented great contrasts between the rural and urban environments.

To the east of Galilee were the ten cities of the Decapolis, all located on the other side of the Jordan River, except for one, Scythopolis (also called Bet Shean). To the northwest, Galilee bordered the Syrophoenician region, with cities such as Tyre, Sidon, and Aco/Ptolemaida. To the southwest was the city of Caesarea Maritima, place of residence of the Roman prefect (later procurator). Finally, to the south was another important city, Sebaste, named after the Emperor Augustus.

In the heart of Galilee there were also two important cities: Sepphoris, very close (5 or 6 km) to the town where Jesus was originally from, Nazareth; and Tiberias, built by Antipas and whose name was a tribute to the Emperor Tiberius. Tiberias was the capital of the Antipas monarchy, and was very close to Capernaum, a city that was probably the main center of Jesus' activity.

It is important to note that the cities were sources of influence of Hellenistic culture. The elites resided in them, while in the rural environment inhabited an impoverished peasantry, from which Jesus most likely came. The cities were generally favorable to Rome, as was shown during the first Judeo-Roman war.

There is no mention in Christian sources that Jesus visited any of the cities of Galilee or its surroundings. However, given the proximity of Tiberias to the main sites mentioned in the Gospels, it is hard to think that Jesus was completely removed from Hellenistic influence.

The peasant environment, from which Jesus came, viewed the cities with hostility. The Galilean peasants bore heavy tax burdens, both from political power (the Antipas monarchy) and from religion (the Temple of Jerusalem), and their economic situation must have been quite difficult.

Galilee was the most troubled Jewish region during the I century, and major anti-Roman revolutionary movements, since the death of Herod the Great in 4 B.C. C. until the destruction of Jerusalem in the year 70, they began in this region. The struggle against the Roman Empire was, according to the historian Geza Vermes, "a general Galilean activity in the first century AD. C.».

Judaism in the time of Jesus

In the time of Jesus, as it is today, Judaism was a monotheistic religion, based on the belief in one God. The Jews believed that God had chosen his people, Israel, and had established an alliance with him through Abraham and Moses, mainly. The fundamental acts of this alliance were, for the Jews, the vocation of Abraham, the exodus, and the promulgation of the law on Sinai. The fidelity of the Jews to this alliance was manifested, in addition to their worship of their only God, in the rigor with which they followed the commandments and precepts of the Torah, or the so-called Mosaic Law; This regulated all aspects of Jewish life, such as the obligation to circumcise male children, the prohibition to work on Saturday, and other certain food rules (for example, not eating pork) and purification.

In the I century, the center of worship to God was the Temple in Jerusalem. It was necessary to go to this three times a year (during the so-called pilgrimage festivals), to perform various sacrifices and deliver offerings. The cult of the Temple was administered by the priests and Levites, whose number was very high, who performed the so-called sacred offices during the festivals, such as guarding and cleaning the Temple, preparing the animals and firewood for the sacrifices, and singing psalms. during public celebrations. The priests and Levites were supported by the tributes of the peasants, obligatory for all the Jews.

But the Temple was not the only place where worship was rendered to God: in the time of Jesus there was also the custom of meeting every Saturday in the synagogues. While the cult in the Temple was dominated by the priests, the custom of meeting in the synagogues was promoting the religiosity of the laity. In addition, in the synagogues sacrifices were not carried out unlike the Temple, but only the sacred texts were read and commented on.

At the time of Jesus, divergent sects existed within Judaism. The author who provides more information on this subject is Flavio Josefo. This distinguishes between three main sects: the Sadducee, the Essenes and the Pharisees. The latter was quite respected by the people and was made up mainly of lay people.

The Pharisees believed in the immortality of the soul and were known for the rigor with which they interpreted the law, considering tradition as its source. As for the Sadducees, a large number of them were part of the priestly caste, but in opposition to the Pharisees, they rejected the idea that tradition was the source of law and also denied the immortality of the soul. Finally, the group of Essenes is considered by the vast majority of researchers as the author of the so-called Dead Sea manuscripts. They constituted a kind of monasticism, whose followers were strict adherents to the law, although they differed from other religious groups in their interpretation of it.

Another very important aspect of Judaism in the I century is its apocalyptic conception: the belief in a future intervention of God, who would restore the power of Israel and after which universal peace and harmony would reign. This idea acquired great force at the time when the Jewish people was subjugated by the Roman occupation (although it is already present in several of the prophetic books of the Tanakh, especially in the Book of Isaiah), and is closely related to the belief in the arrival of a Messiah. In addition, it is frequently mentioned in the so-called intertestamental literature: apocryphal books generally attributed to patriarchs or other prominent figures of the Hebrew Bible.

The Man

Jesus of Nazareth was most likely born around the year 4 B.C. C., although the date cannot be determined with certainty. According to the majority opinion among scholars today, his birthplace was the Galilean village of Nazareth, although he could also have been born in Bethlehem, in Judea, near Jerusalem. His parents were named José and María, and it is likely that he had siblings. There is no record that he was married; he was probably celibate, although there is no source to confirm this either. When he was about thirty years old, he became a follower of a preacher known as John the Baptist and, when he was captured by order of the Tetrarch of Galilee, Antipas (or perhaps earlier), he formed his own group of followers of he. As an itinerant preacher, he toured various locations in Galilee, announcing an imminent transformation that he called the Kingdom of God. He preached in Aramaic, although it is very likely that he also knew Hebrew, the liturgical language of Judaism, both in synagogues and in private homes and outdoors. Among his followers were several women.

He carried out his preaching for an impossible time to specify, but in any case it did not exceed three years, and most likely it was much less. During his preaching, he achieved fame in the region as a healer and exorcist. From his point of view, his activity as a thaumaturge also heralded the Kingdom of God. He was accused of being a drunkard and a glutton, a friend of tax collectors and prostitutes (Mt 11,19), and of exorcising with the power of the prince of demons (Mt, 12, 22-30). His relatives considered him alienated (Mc 3,21). The crowds inspired him compassion (Mt 14, 14) and the only time he spoke about his personality he defined himself as meek and humble of heart (Mt 11-29) but refused to be called good, because only God is good (Mk 10, 18). The living presence of Jesus generated in his disciples a liberating joy: «Can the groom's companions fast while the groom is with them? As long as they have their husband with them, they cannot fast" (Mk 2, 19).

On the occasion of the Passover festival, he went with a group of his followers to Jerusalem. Probably because of something he did or said in connection with the Temple in Jerusalem, although other reasons cannot be excluded, he was arrested by order of the city's Jewish religious authorities, who handed him over to the Roman prefect, Pontius Pilate, accused of sedition.. As such, he was executed, possibly around the year 30, by order of the Roman authorities in Judea. Upon his death, his followers dispersed, but soon after they collectively lived an experience that led them to believe that he had risen and that he would return shortly to establish the Kingdom of God that he had preached in life.

Name

Jesus is the Latinized form of the Greek Ιησοῦς (Iesoûs), with which he is mentioned in the New Testament, written in Greek. The name derives from the Hebrew Ieshu, an abbreviated form of Yeshua, the most widespread variant of the name Yehoshua, which means 'Yahveh saves', and which also designates Joshua, a well-known character from the Old Testament, lieutenant and successor of Moses.

It is known that it was a frequent name at the time, since in the work of Flavio Josefo some twenty characters of the same denomination are mentioned. The form of this name in Aramaic—the language of Judea in the I century—is the one Jesus most likely used: Yeshua (ישׁוע, Yēšûaʿ).

In Mark and Luke, Jesus is called Iesoûs hó Nazarēnós (Ιησοῦς ὅ Ναζαρηνός); in Matthew, John and sometimes in Luke the form Iesoûs hó Nazoraîos is used (Ιησοῦς ὅ Ναζωραῖος), which also appears in the Acts of the Apostles. The interpretation of these epithets depends on the authors: for the majority, both refer to his place of origin, Nazareth; Others interpret the epithet nazoraîos ('Nazoreo') as a compound of the Hebrew words neser ('sprout') and semah ('germ'); according to this interpretation, the epithet would have a messianic character; others, instead, interpret it as a Nazarite (separated for Yahveh). The Dictionary of the Spanish language (from the Royal Spanish Academy) includes the description for the word "Nazarene": 'Hebrew who devoted himself particularly to the worship of God, did not drink any liquor that could intoxicate, and he did not cut his beard or hair.' Quite possibly, in Jesus' time there were a few more men who performed in this way as a religious service.

Place and date of birth

Jesus was probably born in Nazareth, in Galilee, since in most sources he is called "Jesus of Nazareth", and in ancient times the place of birth was often expressed in this way. However, two gospels (Luke and Matthew), the only ones among the canonical gospels that refer to the childhood of Jesus, report his birth in Bethlehem, in Judea. Although this birthplace is the one commonly accepted by the Christian tradition, current researchers have highlighted that the accounts of Matthew and Luke are elaborated with themes from the Davidic tradition, contain several historically unreliable elements, and show a clear intention to demonstrate that Jesus was the Messiah, who, according to Mic 5,2, had to be born in Bethlehem. Many current critics consider that the story of Jesus' birth in Bethlehem is a later addition by the authors of these gospels and does not correspond to historical reality. However, other authors, most of them Catholic, understand that there is no reason to doubt the historical veracity of Matthew and Luke on this point.

Although Nazareth is mentioned 12 times in the Gospels, and archaeological investigations indicate that the town was continuously occupied from the 7th century< /span> before our era, "Nazareth" is not mentioned by historians or geographers of the first centuries of our era. According to John P. Meier, Nazareth was "an insignificant place in the mountains of Lower Galilee, a town so obscure that it is never mentioned in the Old Testament, Josephus, Philo, or the early literature of the rabbis, or the pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament". Although Lk 1, 26 calls it a "city", in reality it would be a poor village that owed all its later importance to the Christian event. The name Nazarenes given to the Palestinian Christians of the I century was undoubtedly ironic and derogatory, and in this sense the name of Jesus accompanied himself with the title "of Nazareth", a dark place that did not favor him at all, as pointed out by Raymond E. Brown.

With the data currently available, it is not possible to specify the year of the birth of Jesus of Nazareth. It is considered a fairly certain fact that the death of Herod the Great took place in the year 4 B.C. C. Hence, when dating the birth of Jesus, the vast majority of authors opt for a range between the years 7 and 4 B.C. C., since there is a probability that the birth occurred in the last years of the reign of Herod the Great. Some authors extend the probable term of the birth to 8 a. C., or 3-2 B.C. C., although these positions are clearly minority today.

Christian sources do not offer an absolute chronology of the events in the life of Jesus, with one exception: Lk 3,1 fixes the beginning of the activity of John the Baptist in "the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius", which can possibly be interpreted as equivalent to one of these years: 27, 28 or 29. A little later (Lk 3,23), it indicates that Jesus was approximately 30 years old at the beginning of his preaching. In addition to placing the birth of Jesus at the end of the reign of Herod the Great, like Matthew, the Gospel account of Luke 2, 1-2 mentions the "census of Quirinus" (whose full and precise name is Publius Sulpicius Quirinius, with "Quirino" or "Cirino" being probable copyist deviations), which raises a historical problem that has not been resolved. In Jewish Antiquities, 17.13; 18.1, the historian Flavio Josefo alluded to a census under Cirino (Quirinio or Quirino) being Coponio procurator of Judea. If Luke's verses are compared with all the historical chronicles about the government of Quirinius in Syria and the census that was carried out under the mandate of Caesar Augustus, it comes to the fact that it is unknown that a census was ordered that "embraced the whole known world under Augustus", and that the census of Judea, which did not include Nazareth, and which was carried out under Quirinius, would have occurred about ten years after the death of Herod the Great, that is, in the year 6 or 7 d. C. and therefore, presumably after the birth of Jesus. It is likely that post factum, that is, after the death of Jesus of Nazareth, his birth was associated with scattered memories of events that occurred a few years before or after the birth itself. On this point, Antonio Piñero pointed out: «The vast majority of researchers believe that Lucas refers «by hearsay» to Quirinio's census of 6 AD. C, therefore about ten years after the birth of Jesus".

Conventionally, the date of birth of Jesus was taken to be that calculated in the VI century by Dionysius the Meager, based on in erroneous calculations and that today serves as the beginning of the so-called Christian era; also conventionally, in the IV century it began to celebrate his birth on December 25.

Family origins

On the family of Jesus, all the gospels agree on the name of his mother, Mary, and his father, Joseph, although two of the gospels (Matthew and Luke) contain different accounts about the miraculous conception of Jesus by the work of the Holy Spirit. According to these accounts, Joseph would not have been his real father, but only his legal father, for being the husband of Mary. Most researchers believe that these accounts are quite late: they are not mentioned in the Gospels of Mark and John, and there are indications that suggest that in Jesus' time he was known as "son of Joseph".

The brothers of Jesus are mentioned several times in the Gospels and in other books of the New Testament. In Mc 6, 3 the names of the four brothers of Jesus are mentioned: James, Joseph, Judas and Simon, and the existence of sisters is also indicated. This mention has been given to different interpretations: Catholics, most Anglicans, Lutherans, Methodists and Reformed, following Jerome, conclude that these were cousins of Jesus, sons of the sister of the virgin Mary, who is sometimes identified as Mary of Cleophas, while the Eastern Orthodox, following Eusebius and Epiphanius, argue that they were Joseph's children from a previous marriage. The rest of the other denominations believe that these were the children of Joseph and Mary.

There are numerous sources that indicate Jesus' Davidic ancestry, through Joseph (although, as noted above, some gospels explicitly state that Joseph was not Jesus' biological father). Several passages in the New Testament show that he was called "son of David", and that the idea of his Davidic origin was widespread in the early years of Christianity although he never referred to himself as such. Critics do not agree, however, that this Davidic ancestry is true, since it may be an addition by the evangelists to demonstrate the messianic status of Jesus. The genealogies of Jesus that appear in Matthew and Luke (Mt 1, 1-16 and Lk 3, 23-31) are different from each other, although both link Joseph, Jesus' legal father with the lineage of David.

Other data: religion, language, profession

The activity of Jesus was inscribed within the framework of Jewish religiosity. From the sources it is inferred that in general he complied with the precepts of the Mosaic Law (although on occasions he disagreed with the interpretation that some religious groups made of it), and that he participated in common beliefs in Judaism of the I (such as the existence of demons or the resurrection of the dead).

Researchers agree that Jesus' native language was Aramaic. Although the Gospels are written in Greek, they contain frequent expressions in Aramaic, most of them attributed to Jesus. Furthermore, Aramaic was the habitual language of the Galilean Jews. Surely the Aramaic spoken in Galilee was a recognizable dialectal variant, as witnessed by the fact that Peter is recognized by his accent in Jerusalem (see Mt 26:73).

It cannot be ascertained whether or not Jesus spoke Greek. It is generally believed that he knew Hebrew, which at the time was only a religious and cultural language, and that he knew how to read, since on one occasion he is shown reading the Book of Isaiah (written in Hebrew) in a synagogue.

It seems that both Jesus and his father, Joseph, practiced the profession of workers, craftsmen or carpenters. In any case, there is quite a consensus that he came from a peasant background. In his preaching he also made constant references to agricultural work, and hardly seems interested in the urban environment (there is no record that he ever visited the main cities of Galilee in his preaching, despite the fact that the important city of Sepphoris was a short distance away). distance from Nazareth).

Your activity

It is not known with certainty how long Jesus' public life lasted. The Synoptic Gospels mention a single Passover feast celebrated by him with his disciples in Jerusalem, during which he was arrested and crucified. That seems to suggest that his public life lasted only a year. In the Gospel of John, on the contrary, three Easter feasts are mentioned, all three celebrated by Jesus in Jerusalem, which suggests that Jesus' ministry lasted for two or three years. In all the gospels there is only one precise indication of the date, the one offered in Luke (Lk 3, 1-2), indicating that the activity of John the Baptist began in the 15th year of Tiberius' mandate, which may coincide, according to different calculations, with the years 27, 28 or even 29 of our era, although most authors favor the year 28.

The public life of Jesus begins, according to all the gospels, with his baptism by John the Baptist in the Jordan River. It is probable that Jesus began his activity as a follower of the Baptist.

Followed by a group of faithful, from among whom he chose his closest friends, the twelve apostles or envoys, his activity toured all of Galilee (especially the area around Capernaum) and the surrounding regions of Phoenicia, the Decapolis and the territory of the Tetrarchy of Herod Philip.

According to Christian sources, his preaching conveyed a message of hope especially addressed to the marginalized and sinners (Lk 15). He possibly came to gather large crowds (he speaks, for example, of five thousand people in reference to the multiplication of loaves and fish). He moved to Jerusalem to celebrate the Passover there with his disciples, and entered the city triumphantly.

Relationship with John the Baptist

In all four canonical gospels, the beginning of Jesus' public life is marked by his baptism by John in the Jordan. John the Baptist is a relatively well-known character thanks to the information about him provided by Flavio Josephus, who affirms that he was "a good man who encouraged the Jews [...] to be just with each other and pious towards God, and to go together to baptism" (Jewish Antiquities, 18, 116-119) and relates that Herod Antipas executed him for fear that he would provoke a riot. John's message, as reflected by the sources, seems quite similar to that of Jesus; according to Matthew, in his preaching he referred to the Kingdom of Heaven and insisted on the need for prompt repentance. The fact that Jesus underwent the baptismal rite suggests that he was probably originally part of the Baptist religious community.

In the gospels, John considers himself a forerunner, declaring that he is not worthy to untie the strap of Jesus' sandals and that Jesus will substitute baptism "in the Holy Spirit" for his water baptism. For his part, Jesus speaks with great respect of John, affirming that "among those born of women there has not risen another greater", although he adds that "the least in the Kingdom of Heaven is greater than he". In the Gospel of John it is suggested that there was some rivalry between the disciples of Jesus and the Baptist, but it is made clear that John always accepted his subordination to Jesus.

It must be taken into account that the gospels were written by followers of Jesus, in order to get new converts. If, as it seems, John the Baptist was a relatively well-known and respected character in his time (as the fact that Flavio Josephus refers to him at length seems to show), it is quite understandable that the evangelists present him as publicly admitting the superiority of Jesus.